Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

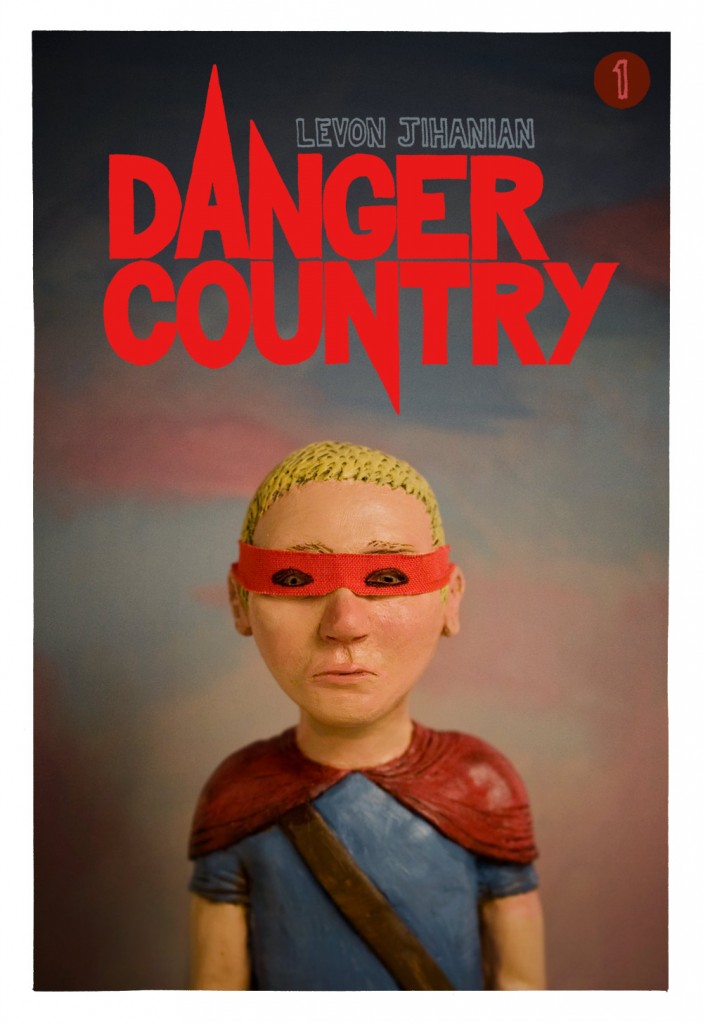

Comics Time: Danger Country #1

December 8, 2011Danger Country #1

Levon Jihanian, writer/artist

Teenage Dinosaur, 2011

40 pages

$5

Buy it from Levon Jihanian

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

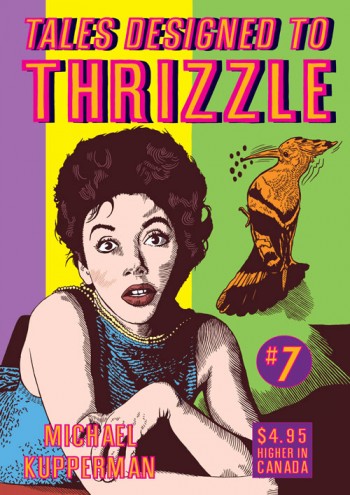

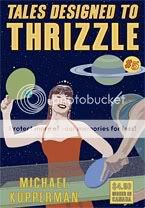

Comics Time: Tales Designed to Thrizzle #7

November 23, 2011Tales Designed to Thrizzle

Michael Kupperman, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, November 2011

32 pages

$4.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Flesh and Bone

November 17, 2011Flesh and Bone

Julia Gfrörer, writer/artist

Sparkplug, 2010

40 pages

$6

Buy it from Sparkplug

Death as an irreparable rupture. Explicit, raw, wounded-animal sexuality. The calculating and casual torture and murder of children. Occult evil that actively belittles the human capacity for love and kindness. It’s tough to think of a darker brew than the one Julia Gfrörer serves in Flesh and Bone, the all too aptly titled tale of a man who’ll do anything to be reunited with his dead beloved and the witch who’s all too happy to accommodate him. But it’s a heady brew, too. Gfrörer’s intelligence shines through in virtually every particular, from pacing (the excruciatingly interminable sequence in which the bereaved man writhes first in agony then in resigned masturbatory ecstasy on his beloved’s grave) to dialogue (a devastating exchange between witch and demon in which love is dismissed as “mutual masturbation,” a form of slavery that prevents humankind from pulling itself out of the muck) to strategic absences of dialogue (a harrowing silent sequence in which an owl is sent to blind a young witness to a horrible crime) to character design (the man’s Byronic good looks, the demon’s disembodied lion head) to facial expression and body language (the witch’s arched back and closed lids as she copulates with a screeching mandrake creature) to a cover that nails the appeal of her wiry, frail characters and line. I can think of few efforts in this vein that impress me, or resonate with me, more deeply than Gfrörer’s. Highly recommended.

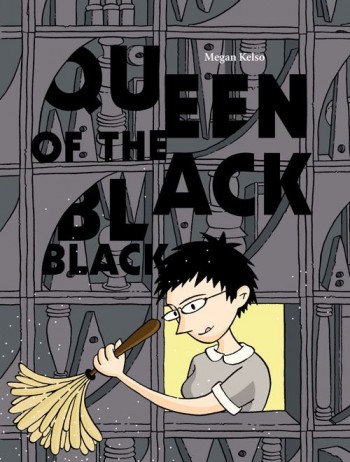

Comics Time: Queen of the Black Black

November 14, 2011Queen of the Black Black

Megan Kelso, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

168 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

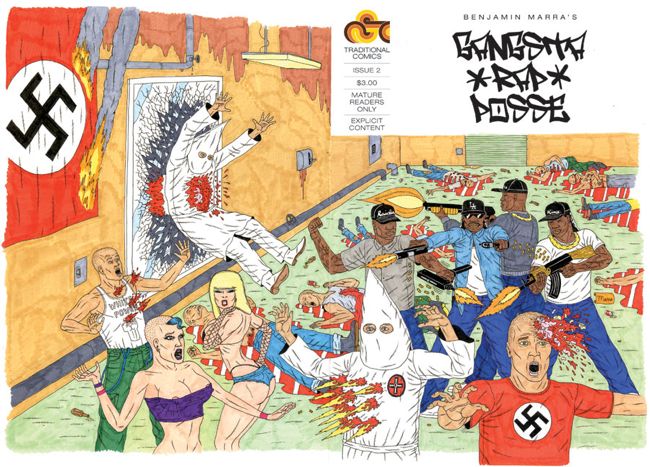

Comics Time: Gangsta Rap Posse #2

October 26, 2011Gangsta Rap Posse #2

Benjamin Marra, writer/artist

Traditional Comics, October 2011

24 pages

$3

Buy it from Traditional Comics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

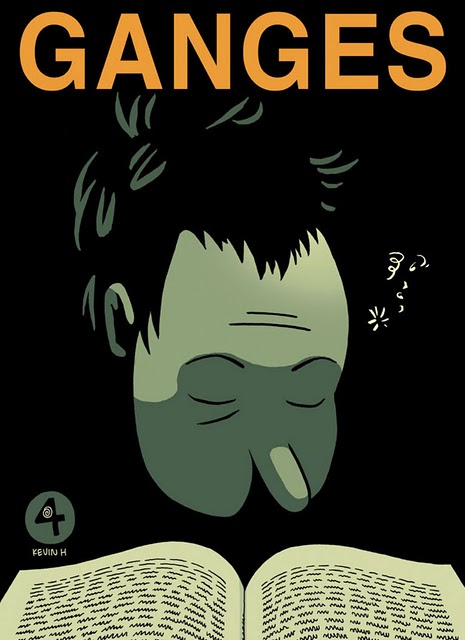

Comics Time: Ganges #4

October 21, 2011Ganges #4

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

Fantagraphics/Coconino Press, October 2011

32 pages

$7.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

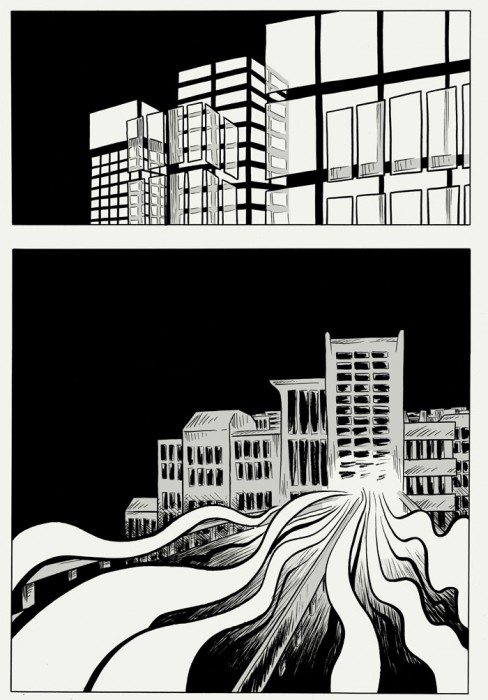

Comics Time: Sexbuzz

October 18, 2011Sexbuzz

Andrew White, writer/artist

Self-published online, 2010-

Currently ongoing

Read it here

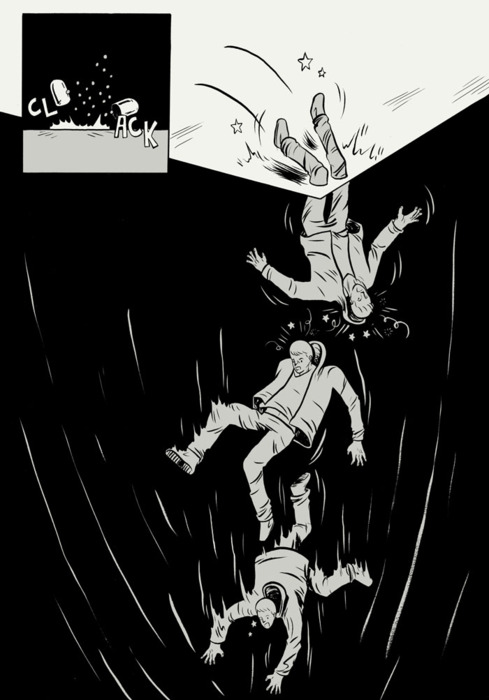

Holy shit. Who is this guy?

Though I first encountered Andrew White’s work through a collaboration with the writer Brian John Mitchell on one of Mitchell’s very tiny minicomics, I didn’t really become aware of White as a creator until a few weeks ago, when (I believe via twitter) I followed a link to his homepage and read this science-fiction sex/spy/slice-of-life webcomic. To say I was impressed would be an absurd understatement. Let me put it this way: I emailed my friends freaking out about him, but refused to tell him his name, because I didn’t want the word going out. A quick google search, in fact, had revealed essentially zero hits. The only person talking about Andrew White was Andrew White, and barely at that. That is nuts.

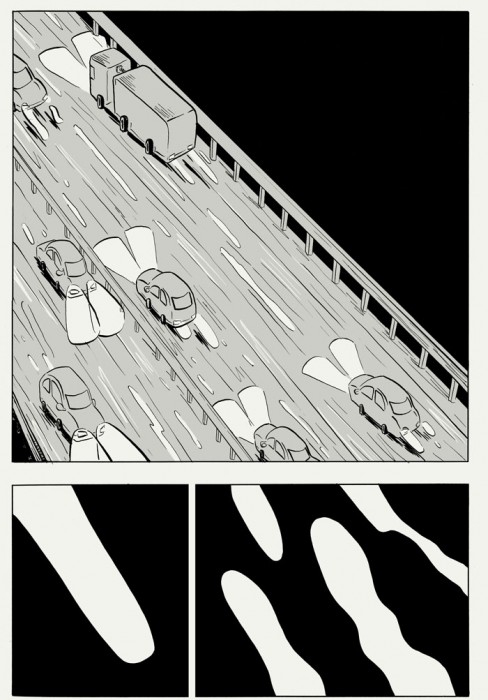

In Sexbuzz, you’ll see a lot of what you like in the comics of Dash Shaw in the way White fuses science-fictional ideas with formal play rather than with set dressing, which in turn gives him the freedom to pursue human-interest storylines without getting tripped up by excessive visual worldbuilding. You’ll see some Ryan Cecil Smith in how he uses loose, almost ramshackle character designs and a fine sense of movement and momentum in his action sequences to make his world feel loose, large, and full of possibility. You’ll see Paul Pope in his big thick ink squiggles, and a fixation on the role of physical objects as a loci of near-future science fiction rather than a more ethereal digital conception of the genre. You’ll even see some Gilbert Hernandez in the way he occasionally pulls back for isolated, abstracted images of the world around us that suffuses it with a weird melancholy magic.

But beyond all the trainspotting, White’s just very good at making the most of the tools at his disposal. The comic’s long vertical scroll gives you the sense of a long story, a story to get lost in, unfurling before your eyes. His graytones are beautifully applied for shading and contour, but also enhance the impression that this is a dingy, rain-soaked city of the night. He’ll slow time down to a crawl with spread-apart panels that evoke McCloud’s infinite canvas without using it outright, then leap forward in time at a chapter break. And he’s constructed the story itself — about underemployed twentysomethings who steal the works for their dangerous technological sex drug Sexbuzz from a sinister corporation — with ample room to play in any number of genres: sci-fi spy thriller, a satire of the corporate/security state, alt/lit young-person relationship drama, action, romance, even erotica. (The nakedly transactional exhibitionism of that opening chapter is hot stuff.) Like Jesse Moynihan’s Forming before it, it’s the kind of webcomic you dream of stumbling across. Long may it run.

(Here are a few pages.)

Comics Time: Thickness #2

October 17, 2011Thickness #2

Angie Wang, Lisa Hanawalt, Michael DeForge, Mickey Zacchilli, Brandon Graham, True Chubbo, Jillian Tamaki, writers/artists

Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge, editors

self-published, October 2011

60 pages

$12

Buy it from the Thickness website

Anthology of the year? I’d need to double-check some release dates, but it certainly seems that way to me. The second installment of Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge’s art-smut comics series is an intense, diverse collection of sex comics, beautifully printed and rich enough to revisit well after your first virgin read.

Michael DeForge, god help us all, continues his juggernaut run with what could well be his best comic yet. “College Girl by Night” stars a young man who’s transformed by the light of the full moon into a beautiful young woman, and uses the time to seduce and fuck college boys. His/her narrative captions don’t comment on the night-in-the-life activities depicted in the art, but rather explain the background of the transformations, her preferred conquests (tired of her “spoiled, drunken nineteen-year-olds,” she’s “made vague plans to set my sights on Edgeton professors, posing a student seeking advice after hours”), her almost idle questions about the science of it all (“Maybe if I got pregnant, it would only show when I transformed. If I even have a uterus, that is”), fictional precedents (“When Billy changed into Captain Marvel he wasn’t technically ‘transforming’…he was having his Billy Batson body physically replaced with an entirely different Captain Marvel one”), and daydreams about starting a relationship while in female form (“I once found a Missed Connection written about me on Craigslist”). It’s funny stuff, featuring DeForge’s trademark juxtaposition of the fantastic and the mundane. But it’s also really, really hot stuff. His character design for the main character’s female form is a note-perfect assemblage of alluring details: spagetti-like tendrils of hair, a dusting of freckles, a short and nearly translucent dress, long lashes that flutter when she throws her mouth open in ecstasy. But then DeForge takes the ruthlessly (if ironically) heterosexual nature of the situation (as she herself puts it, “Is it hugely unimaginative that during my time as a woman, the only activities I’ve done so far is fuck myself or get fucked?”) and crashes it right into its own subtext, reversing the transformation mid-coitus and presenting the two college guys now present on the scene with the opportunity to pick up where they left off, or not. Even if your door doesn’t swing in that direction, there’s a willingness to be led solely by pleasure and desire, a “Shhhh–no one can see, so why not?” quality, that’s hard to deny.

Brandon Graham’s “Dirty Deeds” is the most lighthearted of the contributions (well, aside from True Chubbo’s), and his sense of humor isn’t mine. It’s got this bigfooted vaudevillian underground schtickiness to it that’s just not my thing unless it’s Marc Bell. (Lots and lots of puns: “prostate of shock,” “cervix with a smile,” “I was young, I needed the monkey” — that last one’s a bit of a long story.) But that’s not to say that a breezy sex romp isn’t a welcome addition to this issue’s 31 flavors. Certainly Graham’s warm, curving line is shiny and happy enough to make up for a few jokes that leave me cold, and it’s fascinating watching him use it to achieve certain unique effects — the way he crams detail into limited segments of the page, piling line on line like a soft-serve ice cream cone, while letting the rest of the page breathe, say, which in turn lets him work wonders with images of massive science-fictional scale. And he really makes the most of Sands’s red-orange risograph’d coloring, particularly with his vivacious heroine’s hair and a sexy tan-line effect using what looks like the world’s tiniest zipatone dots. I’m kind of amazed that anything would give this Adrian Tomine print a run for its money in the “Sexiest Use of Tanlines 2011” sweepstakes, but there you have it.

Mickey Zacchilli’s contribution is the most off-model of the bunch, a melancholy affair in which a Brian Chippendalesque lost girl loses her wedding ring and therefore enters some weird subterranean sex chamber, in which a brawny beast and a “slime worm” have their way with her as she worries about other things. What keeps her going is the promise of ice cream on the other side of the chamber, but the showstopping reverie begins with the phrase “All I could think about at that moment were all the various objects that I had never stuck in my vagina.” Arrayed in the closest thing to a clinical grid as Zacchilli’s noisy, scratchy line can muster, this assortment goes from “Yeah, okay, feasible for a curious young woman” (“screwdriver,” “chisel tip Sharpie permanent marker”) to “uh-oh” (“rawhide dog bone,” “rotting arm,” “disembodied head”). When added to the brusque treatment she receives from the creature who lets her in — “Thru the door Alice, Jeanette, Angie, whatever” he says, her identity unimportant — and her tears when she discovers the ice cream shop is closed, it makes for a distressing portrait of disconnect between mind and body, thought and deed.

Dare I call Angie Wang’s contribution erotica rather than smut? Wang offers a four-page start-to-finish portrait of two women — one seemingly shy or hesitant, the other taking charge — having sex. Each panel depicts a discrete body part or moment of connection. It’s a familiar panoptic effect for this kind of thing, and I usually find it to be a bit false to the experience of sex, presenting it as a sort of greatest-hits grab bag rather than a journey from start to finish where the momentum, the upping of the ante from moment to moment, is key. But Wang cleverly jettisons the mishmash approach with an array of techniques: ratcheting the panel grid back from page to page, from 16 to 9 to 4 to a final, climactic (pun intended) splash page; using tangents to connect one panel to the next; paring away dialogue and sound as she goes; altering the focus of each page, from foreplay to initial genital contact to climax to afterglow. Whether despite or because of its delicate, painterly line, it’s got oomph.

Lisa Hanawalt’s contribution is profoundly Hanawaltian. Using the tried-and-true porn setup of the teacher with the hot student, she subverts (or heightens, depending on what you’re into) the fantasy by having the pair’s taboo rendez-vous take place in full view of the rest of the class; the teacher doesn’t even stop delivering his lesson on unreliable narrators (“the narrator makes mistakes” he says as he unzips his fly). Hanawalt apes the male focus on individual body parts with alarming accuracy: “Oh god, her tits! Tiiiiiits…And that ASS,” thinks the teacher over a series of panels focusing on the student’s curves with that familiar combination of thumbs-up celebration and lizard-brain leer. Oh, did I mention she short-circuits the whole thing by giving the girl the featureless conical head of a worm while stuffing her cleavage with fibrous miniature worms, and by giving the bird-headed teacher a penis that itself ends in a bird’s head, which literally vomits its semen all over her ass and vagina when he pulls out? When she slaps a David Lee Roth-referencing “CLASS DISMISSED!” on the final panel, I’m not sure whether to run for the door or stay for extra credit.

The final two contributions hearken back to Sands’s zine roots: Ray Sohn and his anonymous wife serve up one of the funniest, grossest True Chubbo strips to date (you’ll love the Lawrence of Arabia “NO PRISONERS!” quote, especially once you see the context in which it’s being quoted), while Jillian Tamaki’s centerfold pinup intrigues with its incongruous details — a monumental topless woman kneels amid lush flowers and a small army of Russian doll-like people-shaped dildos (I think?), her implacable gaze juxtaposed with her very human bikini-area stubble and a big goofy digital watch on her wrist. They give Thickness #2 a welcome diversity of form as well as content, a “hey, here’s everything that was fit to print” feel.

Thickness #2 is the real deal: talented, fearless cartoonists working in that viscous red zone of pleasure, terror, filth, and fun where the only thing that matters is what the body does and doesn’t want, and your brain is simply forced to go along for the ride. Bravo, thumbs up, panties down.

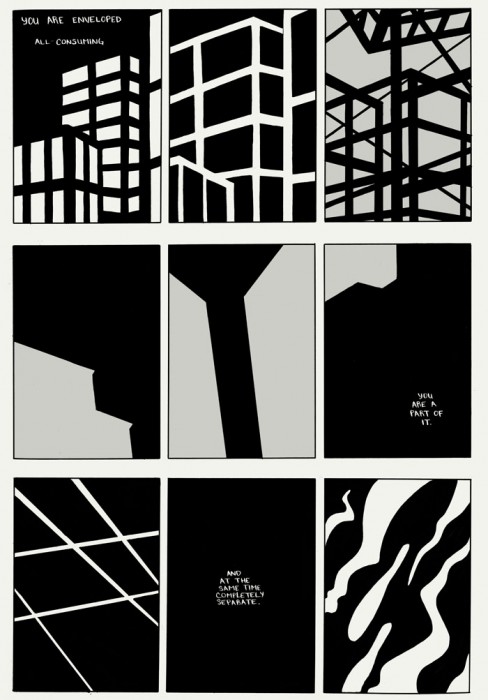

Comics Time: Daybreak

October 13, 2011Daybreak

Brian Ralph, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, 2011

160 pages, hardcover

$21.95

Buy it from Drawn & Quarterly

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

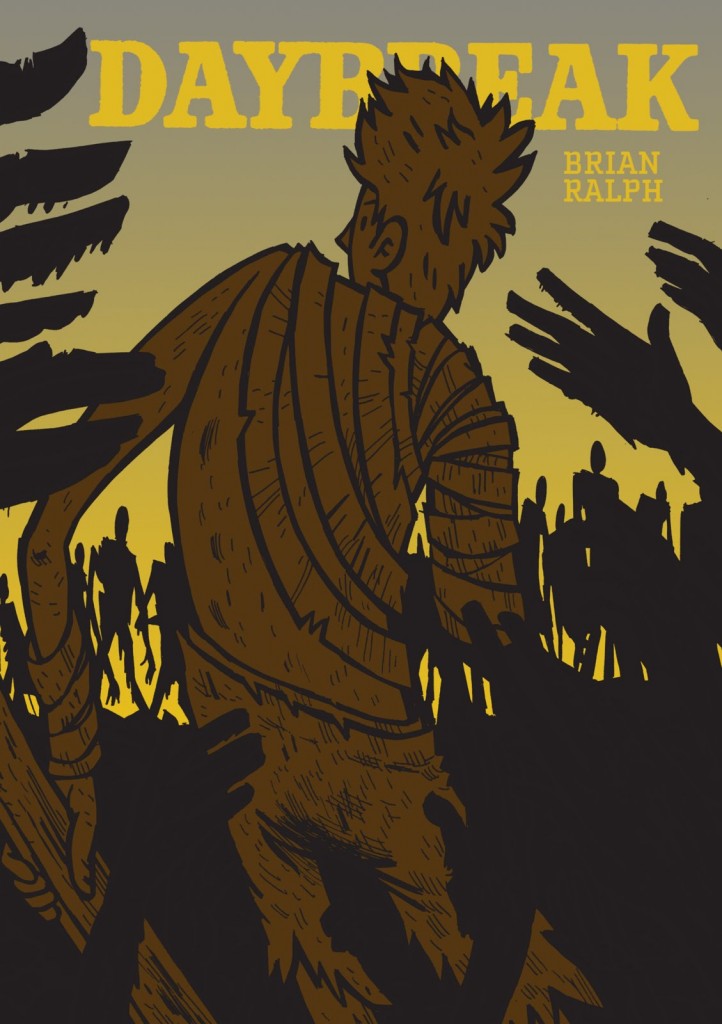

Comics Time: Love from the Shadows

October 5, 2011Love from the Shadows

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

120 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For reasons unknown to me, I did not create a Comics Time entry for this review, which was posted on April 20 at The Comics Journal. I’m just rectifying the situation now. Please visit TCJ.com for the review.

Comics Time: Prison Pit: Book Three

September 28, 2011Prison Pit: Book Three

Johnny Ryan, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, September 2011

120 pages

$12.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: “Touch Sensitive”

September 23, 2011“Touch Sensitive”

Chris Ware, writer/artist

McSweeney’s, September 2011

14 pages

99¢ (in-app only)

Download the free McSweeney’s iPad app, then purchase it in the app’s store

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

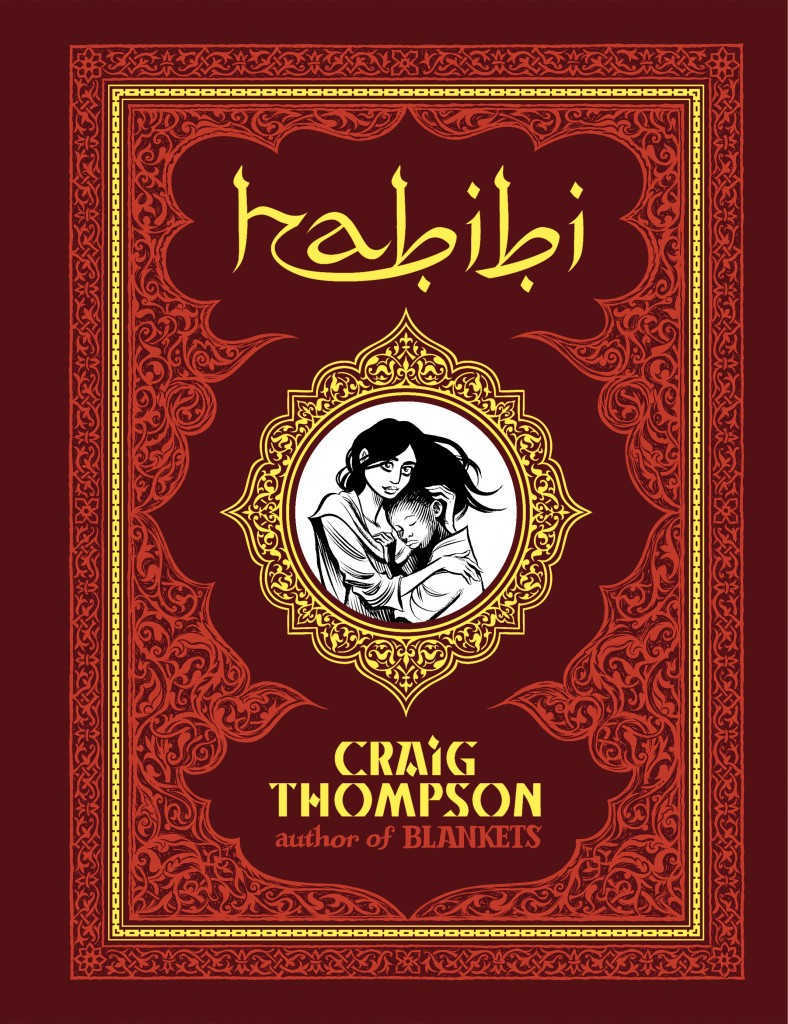

Comics Time: Habibi

September 20, 2011Habibi

Craig Thompson, writer/artist

Pantheon, September 2011

672 pages, hardcover

$35

Buy it from Amazon.com

Fifteen observations about Craig Thompson’s Habibi:

1. This is not a book about Islam. It’s not about any varieties of Islam — contemporary, ancient, fundamentalist, militant, or otherwise. It’s a book infused with Islamic art, culture, thought, and religious beliefs, certainly, but it’s not about Islam. This is another way of saying it’s not about 9/11, al Qaeda, Iraq, Afghanistan, Palestine, Iran, any specific Muslim countries, Muslims in America, uniquely Muslim varieties of misogyny, the Arab Spring, or any other contemporary news-story topic. I first talked to Thompson about his plans for Habibi in the summer of 2003, and in that context and over the course of many of the years to follow it was tough to think about the book without thinking of it one or more of these ways, but no, that’s not what it’s about.

2. This is a book that uses Islam to do other things. On a visual level, it gives Thompson a set of design elements, from calligraphy to ornamentation to architecture to dress to geometrical art, from which he can build a coherent visual world for his vaguely fantastical/post-apocalyptic/dystopian story. Not coincidentally these elements dovetail with his preexisting preoccupations as an artist, from swooping fabrics to obsessive-compulsive design filigrees to religious iconography.

3. It follows that the book is consciously, knowingly Orientalist, as you’d expect and hope of a book that’s using actual Islamic art as bricks in a fantasy world-building project. It’s got an Arabian Nights vibe. Thompson’s invoked Edward Said on this score and everything. To the extent that potentially problematic caricatures of Arab and African race are involved, and they are, they are at least consciously evoked.

4. Islam also provides Thompson with a back door into talking about religion and God — even recognizably Christian elements thereof, thanks to the presence in Islam of Jesus, Solomon, Abraham et al — without needing to rely on the brand of American evangelical Christianity in which he was immersed growing up and which he’s already explored in Blankets. At times the commonality between the issues he discusses in the two books is quite striking. For example, there’s a plotline here about how the bifurcation of Islam and Judaism/Christianity can be traced back to which son you believe Abraham was supposed to sacrifice, Isaac or Ishmael, that’s basically just Blankets‘ bit on scriptural malleability (“The Kingdom of God is within or around you”) blown up to world-historical scale. The impact of religious belief on the development of adolescent sexuality is a centerpiece of both books as well.

5. This is a book about sex. Even if there’s nothing in it that would earn the book anything more than an ‘R’ rating, it works through some violently ambiguous and conflicted feelings about sex in relatively explicit fashion. It took my wife reminding me that Craig first described the book as starring “a eunuch and a prostitute” to help me crystallize that, but there it is. And it makes sense, given the play-it-to-the-balcony tone of Thompson’s previous book, Blankets, and its autobiographical protagonist’s all-or-nothing approach to falling in love and making art, that this book would coalesce around those two poles as well. It is very frankly about the liberating and destructive power of both desire and the denial of desire. (To hearken back to the Arabian Nights element, here’s a tell: Instead of delighting the king with her stories for night after night under penalty of death, the central female character must delight him with sex.)

6. This is a book about many other issues that overlap with or orbit around sex in the popular imagination. They’re not sex, but they’re talked about in the same breath more often than not. They include rape, molestation, prostitution, pregnancy and childbirth, gender, misogyny, a panoply of queer identities, self-injury, puberty, motherhood, male-female friendships, sex and race, sex and organized religion, sex and spirituality, sacrifying sex/orientation/gender, masculinity and femininity…

7. The emotional and physical stakes for the characters are much higher than they are in any of Thompson’s previous works. This is established within the first few pages, in which a child is raped. A bloody sheet is held up to the child and the audience, the blood of her vagina on the blank white fabric equated with the letter-writing in Chunky Rice; the footprints on snow and drawings on paper of Blankets; the act of Creation itself — “From the Divine Pen fell the first drop of ink.” Violence and abuse are the lifeblood of the story.

8. Thompson’s art is much, much denser here than I’ve ever seen it before. It’s still lush and lovely on a surface level, his line still swoops and curves in a fashion he’s explicitly compared to handwriting, but there are more panels on the page, more black in the panels, few of the vast fields of white Blankets was known for, and few of its splash pages too. Decorative patterns of intricate detail are copied from Islamic texts by hand, and drawn repeatedly until they cover almost all the available space on a given page, also by hand. It’s a much tougher book for your eyes to breeze through.

9. Maybe the best way to symbolize that is in the new panorama Thompson has added to his repertoire. He’s said, and promotional art for the book has made use of the fact, that Good-Bye, Chunky Rice had the ocean, Blankets had the snow, and Habibi has the desert. That’s true, but Habibi heavily features vistas of another sprawling, enveloping sea: a man-made sea of garbage. It’s as dense and detailed and chaotic as the water, snow, and sand are unified and simplified.

10. The book is designed. Designed in the Watchmen symmetrical-issue sense. Each of its nine chapters corresponds to a box in the Islamic religious/mathematical talisman known as a magic square — a sort of spiritual sudoku — and its corresponding letter of the alphabet. Each corresponds to a specific topic, and a specific prophet of Islam used to illuminate that topic. But unlike Alan Moore, Thompson doesn’t foreground his machinations. This stuff is present, but in its way it’s beside the point. I didn’t even notice.

11. In much the same way that light, electricity, and information functioned as the stuff of life in Grant Morrison’s Final Crisis, fluid is the stuff of life here. Water is crucial to the various societal strata’s survival within the drought-stricken world of the story. Blood is crucial to nearly all of the book’s depictions of both sex and violence, the fuel of human physicality. Ink is crucial to the characters’ understanding of the nature of God and the world via holy texts and art, and to the author’s understanding of what the hell he’s been doing for the past eight years. There’s less semen or vaginal secretion than you’d think, but otherwise it’s a book about fluids, and fluidity. The greatest sin is staunching the flow, which is done in various ways — a metaphor that extends from environmentalism to art to, of course, spirituality and sexuality.

12. The relative lack of emphasis on sexual fluids is a leading indicator of where the book ultimately pulls an important punch. There’s a revelation, an exposure, toward the end of the book that we readers do not get to see. Since the book confronted virtually everything else it tackled so head-on, since it was so in-your-face about violence and sexuality, you really feel this revelation’s visual absence. Which is maybe appropriate, given what’s being revealed, I dunno. But it left me wondering “Why didn’t he show that?”, in a way that suggests it’s a misstep.

13. The book contains two of the toughest depictions of mental illness I’ve come across in comics. One in particular involved postpartum depression and was deeply sad to me. The other comes hot on the heels of the book’s single most unpleasant depiction of the cruel fate of children in this world. Actually, nearly everything involving children is rough stuff here. There’s not a lot of time for innocence.

14. The book contains two pretty rollicking action sequences. If you’ve read as many lousy action comics as I have, it ought to be a pretty great pleasure for you to watch an artist with Thompson’s attention to environment, layout, movement, and pacing choreograph chase scenes and fight scenes. It definitely was for me. And these sequences had the secondary function of release valve for the dense and emotionally oppressive material they helped break up.

15. Actually, the more I think about it, the more I think Habibi is a book of sequences. Maybe this is reinforced by Thompson’s non-linear storytelling, with his male and female leads’ stories shifting backward and forward in time independent of one another, a technique that emphasizes discreet sequences over the overall flow of the larger narrative. But the bathtub sequence (very successful), the dam sequence (this is perhaps the book’s climax, and I’m not sure it’s successful), the garbage man sequence, the childbirth sequence, the eunuchs sequence, the conflicting stories of Abraham’s aborted sacrifice — these are what stick out to me, embedded in the bigger picture. They’re what will draw me back into the book, moving backward and forward through the work of a cartoonist working out his personal obsessions on the grandest canvas imaginable.

Comics Time: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century: 1969

September 14, 2011The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969

Alan Moore, writer

Kevin O’Neill, artist

Top Shelf, August 2011

80 pages

$9.95

Buy it from Top Shelf

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

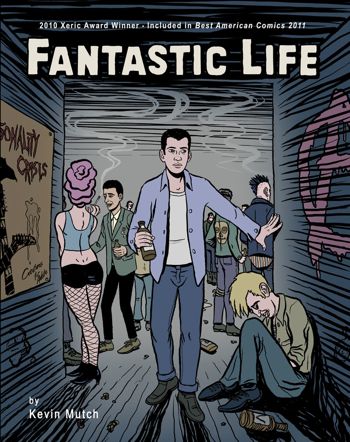

Comics Time: Fantastic Life

August 26, 2011Fantastic Life

Kevin Mutch, writer/artist

Self-published, August 2011

128 pages

No price listed

Read the first chapter at Kevin Mutch’s website

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Have a Comics Time all the time

August 16, 2011I’m pleased to announce that the Comics Reviews section of the sidebar is now fully up to date. All of my recent Comics Time reviews have been added, and all the links lead to the relevant review here at seantcollins.com rather than at my old site. That’s in the neighborhood of 500 reviews. Please browse and enjoy.

Comics Time: Tales Designed to Thrizzle #5

August 16, 2011 Tales Designed to Thrizzle #5

Tales Designed to Thrizzle #5

Michael Kupperman, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2009

32 pages

$4.50

Buy it from Fantagraphics

(Originally posted at this blog’s previous location on May 26, 2009; I am reposting it because it does not seem to have made the move to the current site.)

By now I’ve written about how Kupperman’s humor works at some length, so you’d think it would have occurred to me by now that his humor is an entirely different animal from the vast majority of humor comics. Which it is, insofar as it’s funny and most humor comics aren’t. But it wasn’t until this (ironically) prose-heavy issue that I realized he’s not doing gag comics at all. The only four-panel punchline-driven strip in this entire book, “Ever-Approaching Grandpa,” basically exists to give lie to the notion of the four-panel punchline-driven strip (and is own title). He’s not content with using just the words and the visuals. I think what Kupperman’s doing–with his long, digressive “stories,” with his riffs on old-fashioned comic-book covers, and so on–is using the stuff of comics itself as a locus of the comedy. A grid of panels implies continuity of action, so he uses that to present an increasingly bizarre and disjointed Twain & Einstein adventure with barely any internal cohesion whatsoever. We assume that captions or word balloons will comment on the visuals against which they are juxtaposed, so he creates a how-to arts-and-crafts strip that for no apparent reason is also a brutal noir (“How to Pattern Print with a Potato, Johnny”). We’ve come to accept certain visual cues as meaning a certain thing, so he literalizes them so that they mean something entirely different–a phone in the extreme foreground actually turns out to be a just-plain gigantic phone; a mother’s wagging finger radiates motion lines that turn out to be “super-vibrations.” In his way, Kupperman’s just as concerned with making comics’ formal aspects work for him as Chris Ware. In his way he’s every bit as effective. Goddammit this book is funny.

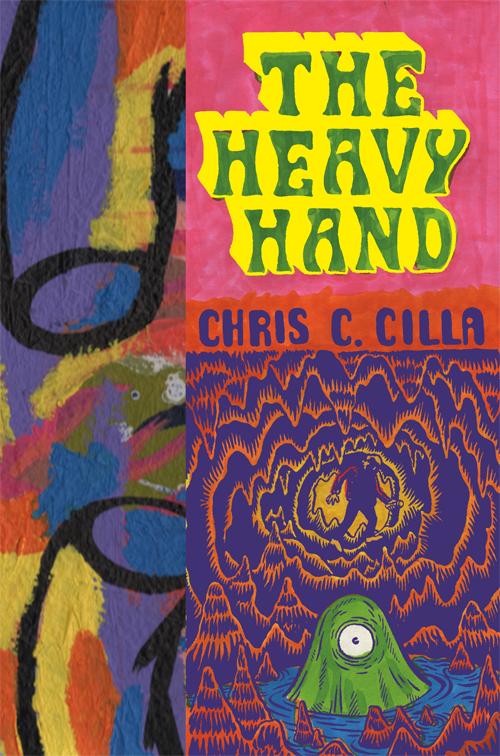

Comics Time: The Heavy Hand

August 10, 2011The Heavy Hand

Chris C. Cilla, writer/artist

Sparkplug, 2010

108 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Sparkplug

Buy it from Amazon.com

Fascinating book, this. It combines the textural, noise-based visual aesthetic of caves and monsters and melty stuff that you may have seen from many of Chris Cilla’s fellow contributors to the Paper Rodeo and Kramers Ergot anthologies with the down’n’out beer-swillin’ shit-talkin’ big-schnozzed characters of ’90s altcomix (big noses are to alternative what big feet were to the underground), so right off the top it’s doing something unexpected. And in the same way that the art is both densely intense and breezily funny, the story somehow coheres from jokey banter, grand-guignol monster attacks, and surreal non sequitur splash pages into an utterly convincing world. The Heavy Hand is basically the tale of Alvin Crabshack, somewhat feckless young guy who picks up stakes and moves from the city to a remote research site in hopes of bluffing his way into the employ of a scientist he admires, at which point he is drawn into a crescendoing series of bizarre science-fictional events — and it works great on both sides of that descriptive sentence’s comma.

Regarding the first half, Cilla’s command of the details of a young life not particularly well lived is substantial. Just for example, look at the way he differentiates between the two women Alvin is (duplicituously) dating by how he dresses both their rooms and themselves — the first has a neat haircut and sits in bed reading one book among many well-ordered shelves, candles and wine glasses strewn here and there; the second we meet as she cracks open a beer and picks a cassette tape off a table sporting a used ashtray and half-eaten dishes, all while bare-ass naked — while giving both sequences a sordid, stiff-nippled sexiness, a squalid heat that comes from lying to someone you know intimately and resent at least as much as you enjoy.

Of course, the second woman has a duck’s beak instead of a nose, which leads us to the strangeness. Obviously this wouldn’t be the first time an alternative comic featured unexplained anthropomorphism in an otherwise realistic setting, so I didn’t pay it much attention — nor the weird, wordless opening sequence in which some kind of ghostly scientist fixes both a machine and a cup of coffee by pissing all over them. But as Alvin’s journey progresses, we come to learn that not only is he basically lying his way into working with his academic idol, but the work he’ll be doing is considerably more odd and dangerous than the book’s opening makes it sound. Rival grant-sponsored teams plumb a system of caverns and underground rivers for giant eggs that contain dead reptiles, while huge and deadly one-eyed protoplasmic creatures devour their pack donkeys…which in turn hearkens back to tall tale about a curse on a nearby town that led to its affliction with these strange animals…which we suddenly realize relates to the odd interstitial splashes and spreads depicting a mustachioed man and giant spiders and so on…which we eventually learn aren’t the non-narrative interruptions they appear to be but an integral part of the story at hand…which culminates in a tour-de-force party sequence where the romantic entanglements and awkward interpersonal interactions of the beginning of the book come back into play. These competing, seemingly clashing narrative and visual threads slowly enmesh and intertwine so organically that you hardly notice, until suddenly you realize they’ve sewn up a structure so sturdy you could spend hours climbing around inside it.

My only complaint is that you don’t get that kind of time. As fun as that party scene is — I really love the way all of the dialogue is disconnected, with never more than two word balloons actually commenting on one another; it’s a great way to convey feeling out of place in an inebriated crowd — it eats up a huge amount of space relative to the densely plotted rest of the book, and rockets everything to its explosive conclusion way too fast. The Lynchian epilogue is as engrossing as anything else in the book, but it made me pine for a nonexistent much longer version, one that didn’t cut itself off right when it became apparent how rich and compelling it was. But since so much of the plot is driven by an anecdote about an inventor whose life basically had to blow up before he could do what would make him rich for the rest of his life, it’s hard for me to get too upset that the book itself follows suit. Wanting more is surely a sign that this smart, biting work of literary science-fiction comics did something right.

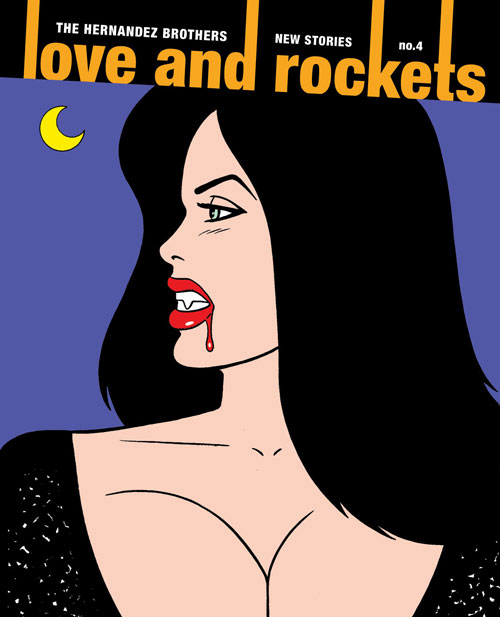

Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

August 1, 2011Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, August 2011

104 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 will turn any fan of Los Bros Hernandez into the host of The Chris Farley Show. “Remember? That time? When you drew Calvin’s plaid shirt? So that the plaid was always facing in the same direction? No matter how much Calvin moved?…That was awesome.” I am seriously finding it difficult, if not impossible, to review this comic without simply hitting the bullets-and-numbering button and whipping up a list of everything in it that amazed me. It would be a long list, too. But I’m abstaining as much as I can — to challenge myself for starters, and to avoid spoiling the comic for those of you who haven’t yet read it (which is probably most of you since it’s not out yet) for the most part. But I’m also holding off on that listicle because I think it’s a cheat. The fact of the matter is that while reading this book I discovered that I’m at least as attached to Ray Dominguez and Fritz Martinez, the protagonists of Jaime and Gilbert’s contributions respectively, as I am to a decent number of real people in my life. So sure, I could rattle off the ways in which Xaime and Beto continually prove themselves to be among the most graphically inventive and entertaining cartoonists alive some three decades into their careers — the crosshatching on Ray’s shirt and Maggie’s sofa; Gilbert’s use of wavy, puddle-shaped, impenetrable fields of black in his vampire story; the impact of the just-this-side-of-parallel lines of Angel’s body as she bends her leg to put on a high heel; the upside-down lava-lamp shape of Fritz’s legs in a skirt, used as an anchor for panel after panel of her simply walking around town with her agent ex; dredging up a long-ago, possibly long-forgotten character, drawing him as a late-middle-aged man in a way that makes him unrecognizable until you realize just how recognizable he is; the smashed-skull-as-cubist-masterpiece in Gilbert’s customary burst of horrifying ultraviolence; the holy shit moment when you realize the visual structure to that montage spread from Jaime’s story; Gilbert storming the ramparts of the vampire story and launching sex and violence back into it like payloads from a trebuchet; Jaime serving up a story whose snapshot style echoes comparable material from “Wigwam Bam” in significant and story-relevant ways; tracing the similarities and differences between Killer and Fritz via the characters they play, the use of their amazing bodies fraught with story information. And hey, look at that, I did rattle them off! But in the end, how it looks pales in insignificance next to what happens, because making it look that good is a means to the end of imparting just how much what happens matters. Ray’s shirt and Fritz’s legs, the shadow of the vampire and the structure of the montage — they’re just landmarks to remind you where you were when you found out if Ray and Fritz and Maggie were going to get happy endings, or not. It’s the easiest thing in the world to understand, and it’s the hardest thing in the world to do, and it’s magic, pure magic, to do it this well.

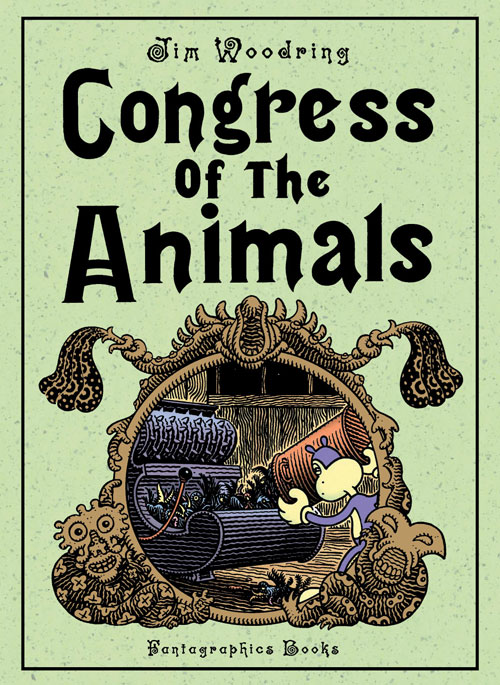

Comics Time: Congress of the Animals

July 27, 2011Congress of the Animals

Jim Woodring, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, June 2011

104 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Buy it and read a preview at Fantagraphics.com

Perhaps I should have seen it coming after the palpable (if fleeting) triumph of good over evil that comprised the climax of Weathercraft, Jim Woodring’s previous standalone graphic novel set in the world of his funny-animal avatar Frank. Regardless, I’ll admit it: I did not expect to read a Frank book whose final panel made me go “Awwww!”

It’s true that in Weathercraft, Frank’s hapless antagonist Manhog achieves enlightenment that for a short while allows him to become an elemental force of kindness, justice, and the security of a fundamentally benevolent order to the universe. But it’s only for a short while — the equilibrium restores itself, and he, the insouciant Frank, and the jauntily predatory Whim go back to their old ways. According to Woodring’s typically dense and hilarious jacket copy, we have the Unifactor, the familiar world of bulbous buildings and shoggoth-like plant deities in which Frank and his cohorts dwell, to thank for this state of affairs. Woodring calls the Unifactor “the closed system of moral algebra into which Frank was born, where “in the end, nothing really changes,” and where “Frank is kept in a state of total ineducability by the unseen forces which control that haunted realm.”

The difference here — and I’m not 100% convinced this would have been clear if Woodring hadn’t said so straight out on the jacket, but be that as it may — is that this time around, Frank leaves the Unifactor. Woodring’s customary Rube Goldbergian plot contrivances force Frank into a state of indentured servitude that ends with him on the lam. The journey positions Frank in the midst of various grown-up concerns, such as home ownership, property loss, commerce, employment, amusement, leisure, sex (in the form of what appears to be an angelic anthropomorphic vagina guarded by the giant disembodied head of a Dr. Seuss character), and religion (in the form of nude, beefy men with gaping chasms where their faces are supposed to be, whose ability to expose their guts at will and induce others to do so literally knocks poor Frank out with its disgustingness and is perhaps Woodring’s most troubling sequence since Manhog flayed his own leg); in other words, it’s a bit like Pippin. Normally we’d expect nothing to come of all this, save for an opportunity to marvel at Woodring’s buzzy, vibrating line, proficiency with creature design, and ability to distill unpleasant shit into slightly sinister slapstick adventures for his dog-cat-bear-mouse-thing hero. But the journey takes Frank so far afield that at some point (probably when he gets lost at sea and washes up on some distant shore) he ends up outside the Unifactor’s confines. New information can now enter his world, in the form of a female Frank-like character who lives in a house shaped like Frank. And at that point all hell breaks loose…which in a Frank comic is to say it doesn’t break loose at all.

Somehow, Frank has gained the ability to interact with another being without immediately sizing up the best way to have fun with, or at the expense of, that being, consequences be damned. They chat. They laugh at the bullying creatures who attacked him earlier, and blush at both having got such a kick out of it. (See, he hasn’t been brushed totally clean of his sins — as we see here and elsewhere, both he and his new pal still have a bit of an empathy deficit.) She protects him from the siren song of that angelic vagina-thing. She helps him return home, to the delight of his pets Pupshaw and Pushpaw, who seem overjoyed to find that their master has found his other half. But what really moved me is their simple physical interaction: They hug. I’m “awwww!”ing just thinking about it. That physical act is an act of grace on Woodring’s part, an escape from the mere hedonism or fight-or-flight responses that have been the sole custom of Frank’s world before now. It’s a new, rewarding emotion, embodied. And despite the break it marks from the world of Frank as we knew it, it fits, since isn’t embodying emotion what Frank stories have always been all about?