Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

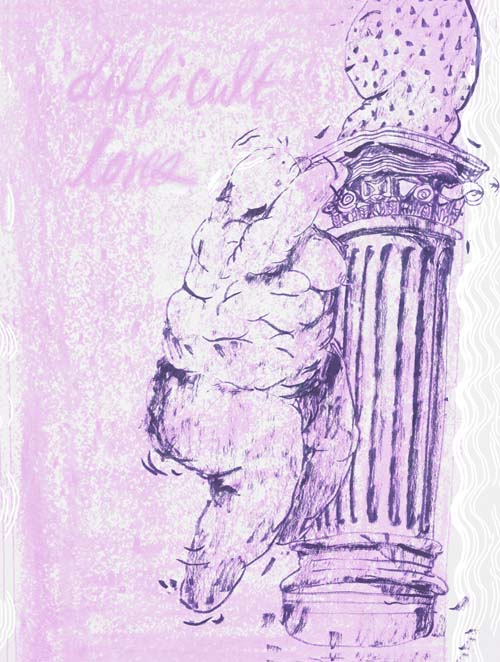

Comics Time: Difficult Loves

May 23, 2012Difficult Loves

Molly Colleen O’Connell, writer/artist

Domino Books, May 2012

24 pages, 2 poster inserts

$6

Buy it from Domino

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

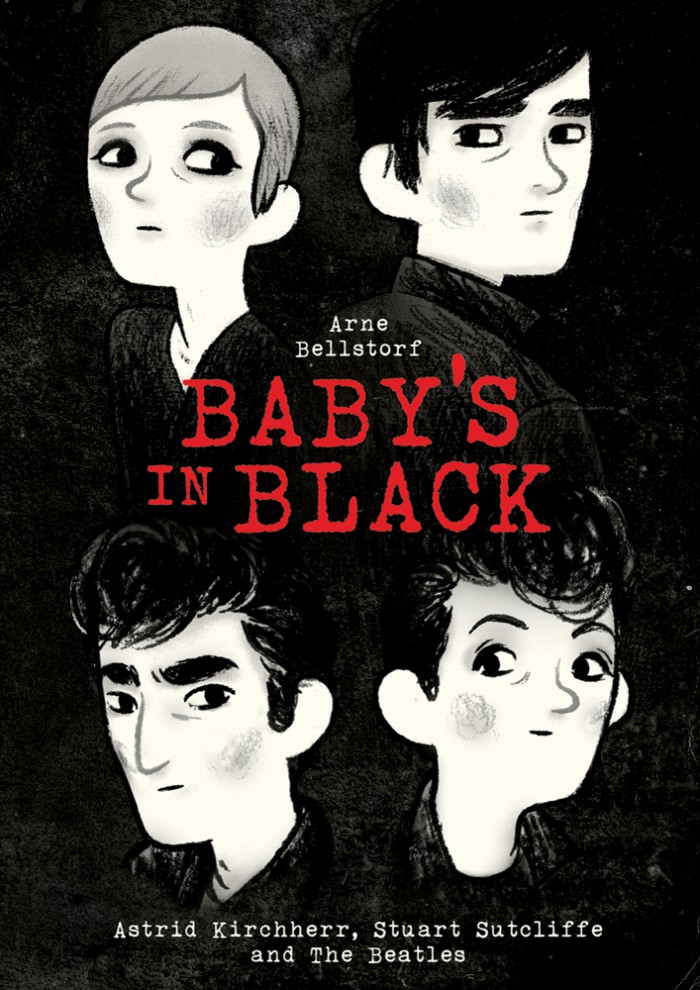

Comics Time: Baby’s in Black

May 9, 2012Baby’s in Black

Arne Bellstorf, writer/artist

First Second, May 2012

208 pages, hardcover

$24.99

Buy it from Macmillan

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

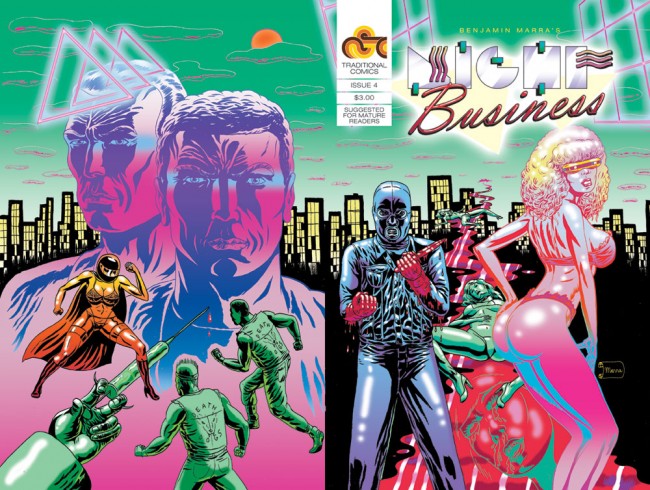

Comics Time: Night Business #4

May 2, 2012Night Business #4

Benjamin Marra, writer/artist

Traditional Comics, 2011

24 pages

$3

Buy it from Traditional Comics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Cyclical, Stale N Mate, Let’s Fucking Party, and Cheek Up’s

April 19, 2012Cyclical, Stale N Mate, Let’s Fucking Party, and Cheek Up’s

Shia LaBeouf, writer/artist

The Campaign Book, 2012

various page counts

Cyclical, Stale N Mate, Let’s Fucking Party: $10 print/$5 ebook

Cheek Up’s: free ongoing webcomic series

Buy them and/or read them for free online at The Campaign Book

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

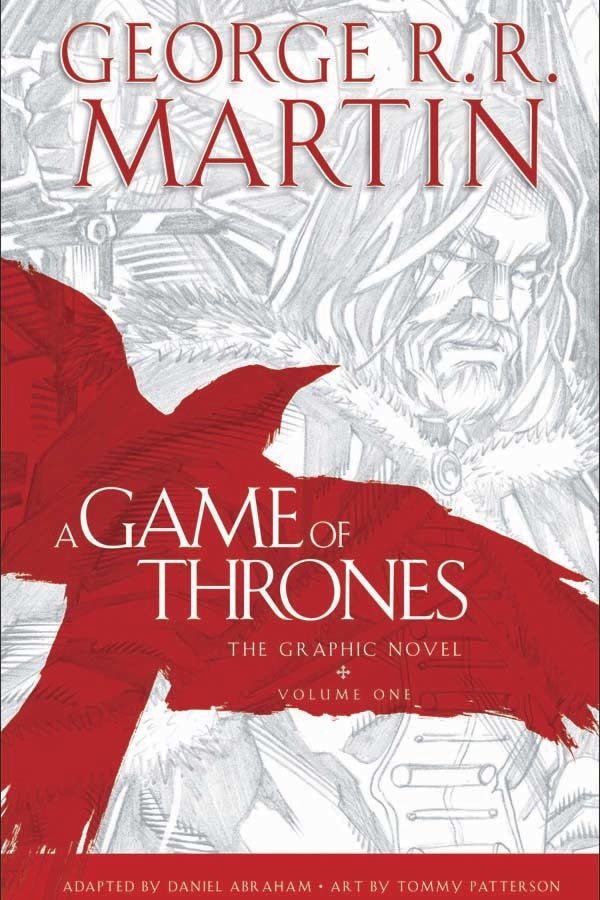

Comics Time: A Game of Thrones: The Graphic Novel: Volume One

April 9, 2012A Game of Thrones: The Graphic Novel: Volume One

Daniel Abraham, writer

Tommy Patterson, artist

adapted from the novel by George R.R. Martin

240 pages

$25

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

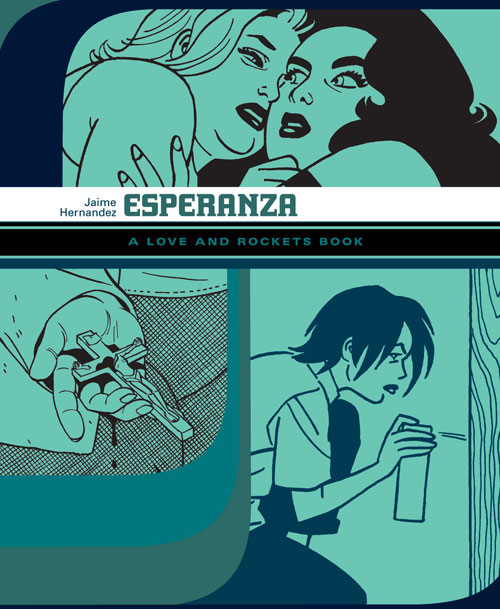

Comics Time: Esperanza

April 4, 2012Esperanza

Love and Rockets Library: Locas, Book Five

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

248 pages

$18.99

Fantagraphics, 2011

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: q v i e t

March 28, 2012q v i e t

Andy Burkholder, writer/artist

ongoing webcomic, May 2011-present

Read it at qviet.tumblr.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: SuperMutant Magic Academy

March 22, 2012SuperMutant Magic Academy

Jillian Tamaki, writer/artist

Ongoing webcomic, December 2010-present

Read it at MutantMagic.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

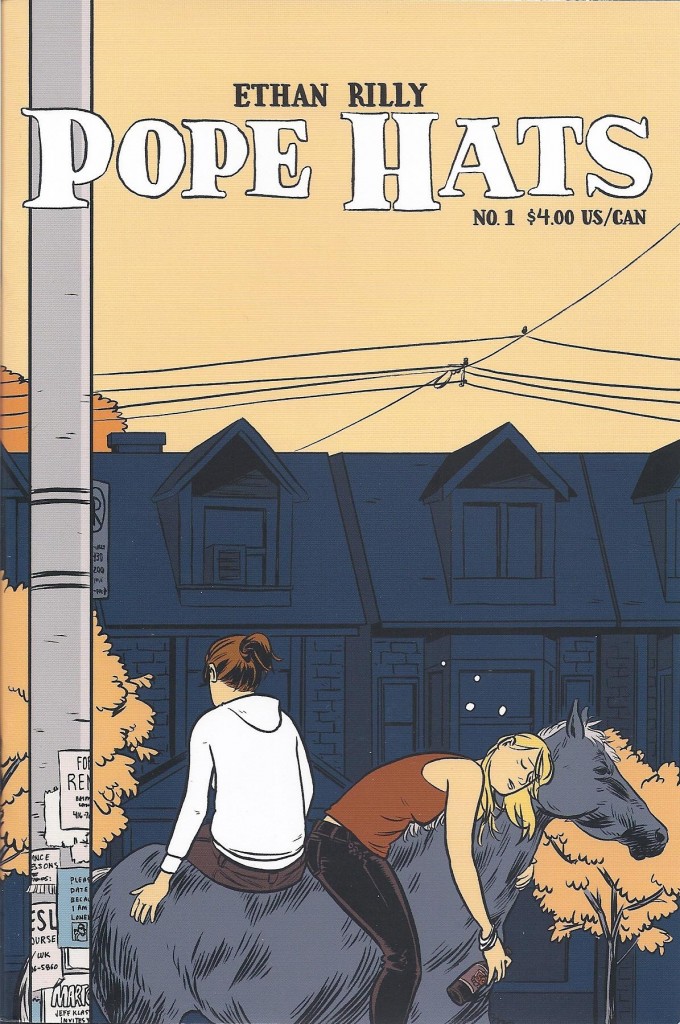

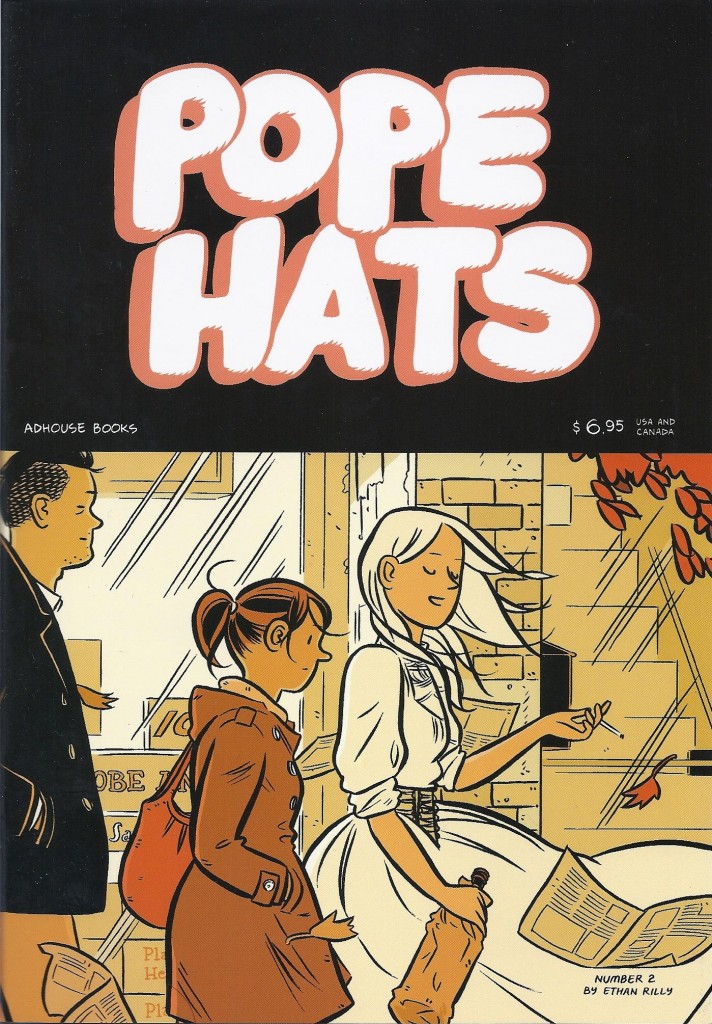

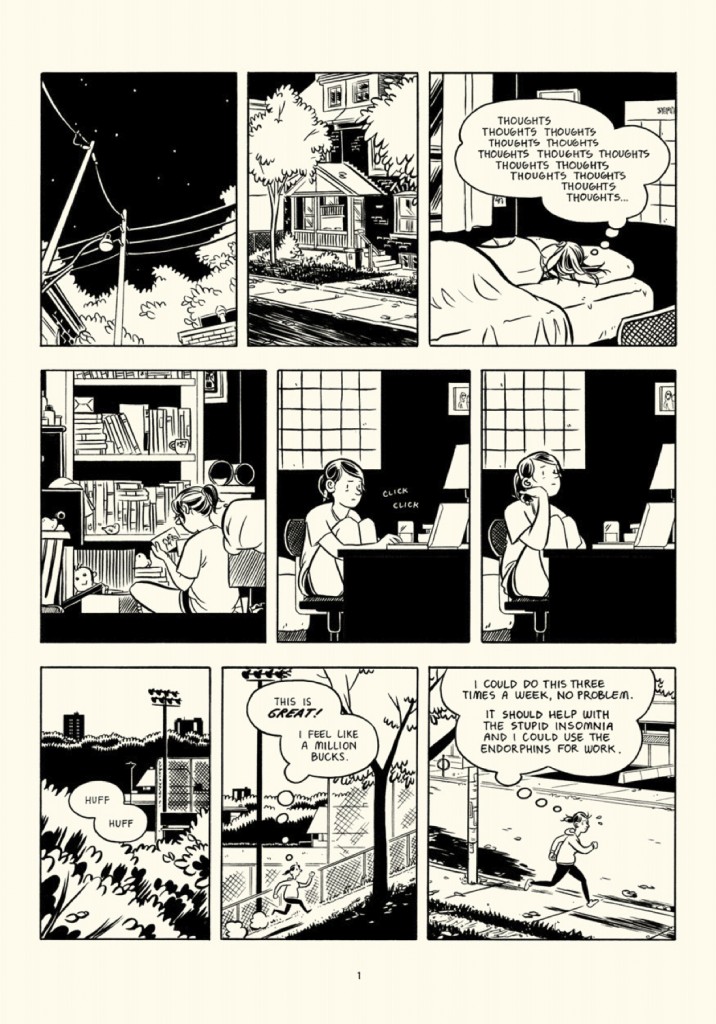

Comics Time: Pope Hats #1-2

March 13, 2012Pope Hats #1-2

Ethan Rilly, writer/artist

#1: self-published, 2009

32 pages

$4

Buy it from AdHouse

#2: AdHouse, 2011

40 pages

$6.95

Buy it and read a preview at AdHouse

You know, I was gonna be harder on these before I started flipping through them again in preparation for actually writing this review? I have no objection to slice-of-lifers, obviously, even stylized ones like these — the kind where everyone’s dialogue is constantly “on” (“Don’t you want to say goodbye to Peter?” “If by Peter you mean ‘my bed’ and by goodbye you mean ‘pass out in,’ then yes. Yes, I want to say goodbye to Peter immediately.”), and where the lead occasionally talks to a cartoon ghost, and has a boss who looks like the Kingpin, meditates in the lotus position in his office, dictates all his correspondence (including grocery lists) to three assistants in lieu of owning a computer, and lives in an adjoining hotel so he never has to go outside. What’s more, Rilly’s cartooning is absurdly proficient and elegant. I wish I could remember who I’m stealing this from because it’s the perfect way to describe it, but you really could sit Rilly down next to his fellow (mostly) Canadians in the core Drawn & Quarterly line-up — Seth, Adrian Tomine, Joe Matt, mid-period Chester Brown — or for that matter next to Los Angeles’ classy classicists Jordan Crane and Sammy Harkham, and he wouldn’t look the slightest bit out of place. But speaking of fellow Canadians (and of Los Angelenos, at this point), there’s a healthy dose of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s comparatively contemporary portraits of young urban semi-professionals in there along with the standard Gray/Segar roots, an influence the aforementioned snappy, showy speech and not-quite-magic realism only make clearer by the end of Pope Hats‘ second issue. The problem is that it’s all a bit too dazzling to actually get into, at least for me. Every word uttered, every gesture gestured by studious law-clerk lead character Frances and her drunken whirligig actress roommate Vickie is designed to drive home just how them they are at all times. If the story, such as it is at this point, is one of young people feeling locked into the personae and professions they’ve chosen themselves, then Rilly’s conveying this all too well — I never felt like the characters had been given the freedom to surprise him or me. (You could perhaps say the same for the whole package as comics, if you were feeling less than charitable. The random-ass title, the self-effacing tone of various bits of incidental copy here and there, supplementary short stories in which ironically verbose schmoes wax philosophical about the ineffable joy and dread of modern life — the only way it could be more of a ’90s altcomix solo-anthology throwback is if it had a letter column full of people asking permission to turn it into a student film.)

But that’s all just how I remembered the comics from my initial read; much of it vanished upon that aforementioned flipthrough, which ended up feeling like a tour of Pleasuretown. For all I may object to the flippant patter, Rilly has a terrific eye and ear for the intersection between a person and her job, and how what she does during work hours and off hours alternately aligns and contrasts in revealing ways. Vickie is a manic pixie dream girl for guys and something of an alcoholic trainwreck for her roommate Frances, but she’s also a compelling actress in local productions. Frances is dutiful at work and at home to the point of drudgery/neurosis, but she tells a pair of spooky true stories at the end of issue #1 — in medium-closeup direct-address Brian Bendis fashion, no less — that both showcase how well comics can do that sort of thing and demonstrate how her attention to detail can manifest itself as an engaging facet of her personality during her free time. Issue #2’s backup story “Gould Speaks” hits its “intellectual blowhard actually quietly emotionally wrecked by a breakup” note a little hard for my taste, but watching Rilly fill out the space of the bus on which the title character is taking a cross-country trip by almost constantly shifting angles from panel to panel is a multi-dimensional joy, and when the true meaning of the story’s title is revealed, I laughed out loud. And of course there’s the fact that Rilly is a fucking phenomenal drawer — of hair, of ceiling fans, of city streets, of bar interiors, of beds, of pretty much anything. See the cover of issue #2? The inside’s just as pretty. It’s that kind of comic. In other words it’s a good kind of comic — it could be better, yeah, but isn’t that what issue #3 is for?

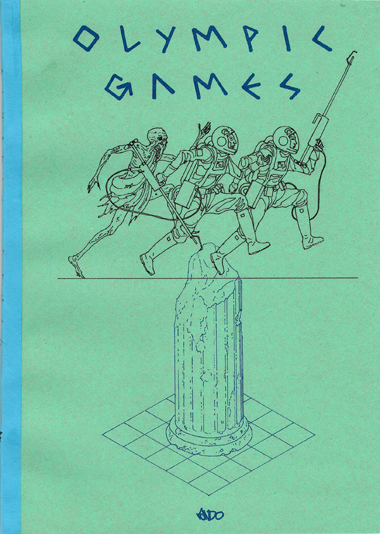

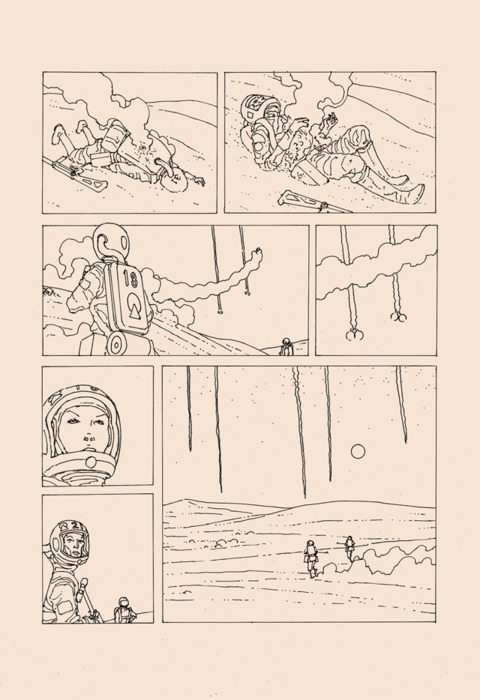

Comics Time: Olympic Games

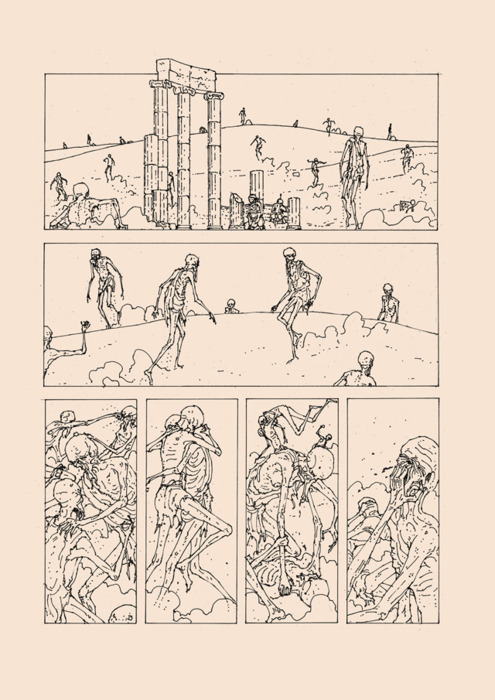

February 27, 2012Olympic Games

Lando, writer/artist

Decadence Comics, 2012

44 pages

£10 including international shipping (cheaper in the UK)

Buy it from Decadence

I went back and forth about opening this review with “Whoosh, is this thing good,” but the ayes have it: Whoosh, is this thing good. In fact it’s fair to say that I returned to semi-regular reviewing of comics in large part to have an excuse to read this remarkable-looking self-published small-print-run science-fiction adventure and write about it publicly. The unique, tactile packaging helped draw me in: It’s printed on that rough, cheap paper your third-grade handwriting practice workbooks came on, with a weary-looking blue cardstock/construction-paper cover to boot. But the content is just as fascinating, particularly writer/artist/publisher Lando’s ultrathin, ultraprecise line. It looks as though he took the finest-point rollerball pen available and went about painstakingly constructing each laser-toting astronaut, each toga-wearing revenant, and each weathered Greek column and angular laser beam and grain of sand in their eerie retrofuture wasteland by stopping every few millimeters or so, picking up the pen, putting it back down, and starting the line again, just to make sure he got it right. “Scratchy”‘s the word that keeps presenting itself to me, but it’s not the right one at all. There’s a meticulousness to this roughness that scratchy doesn’t cover, and it elevates the SF story, about a pair of visitors from space attacking their enemies — both living and dead — and defending one another as they make their way toward some maguffiny goal in the center of what looks very much like Greek ruins, but for the desert wasteland surrounding them. That particular irony of setting, and the titular reference to the coming spectacle of sport in the artist’s native country, indicate that this could very well be a scathing metaphorical commentary on kill-or-be-killed austerity economics and its beneficiaries. (Indeed, the artist makes that pretty clear on his website, though I’m loathe to lend too much credence to authorial intent.) Personally, I missed the Hunger Games/Running Man bread-and-circuses nature of the action on first read and instead read it as a savage, though savagely thrilling, war comic of sorts. Either way, Lando’s skill with pacing and action choreography is tough to match among people making these kinds of alt-SFF comics today; his perspectival cross-cutting between embattled areas, and his use of blankly linear lasers to traverse that space and shift our viewpoints, is especially exciting. All told it’s the kind of comic where the main shortcomings are best expressed as matters of personal preference — it’s wordless and soundless, while I tend to feel that silent comics make the most sense when the events depicted involve actual silence; it uses irregular panel layouts, while I believe the elegance of a fixed grid would have been quite complementary to the precision of the linework and character/set design. If this kind of thing sounds at all like your bag, and if you’re reading this blog chances are it does, fire up your currency converter and hope he’s got some copies left.

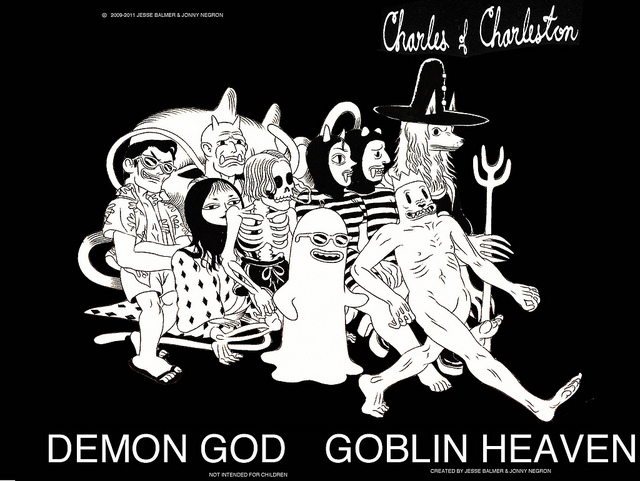

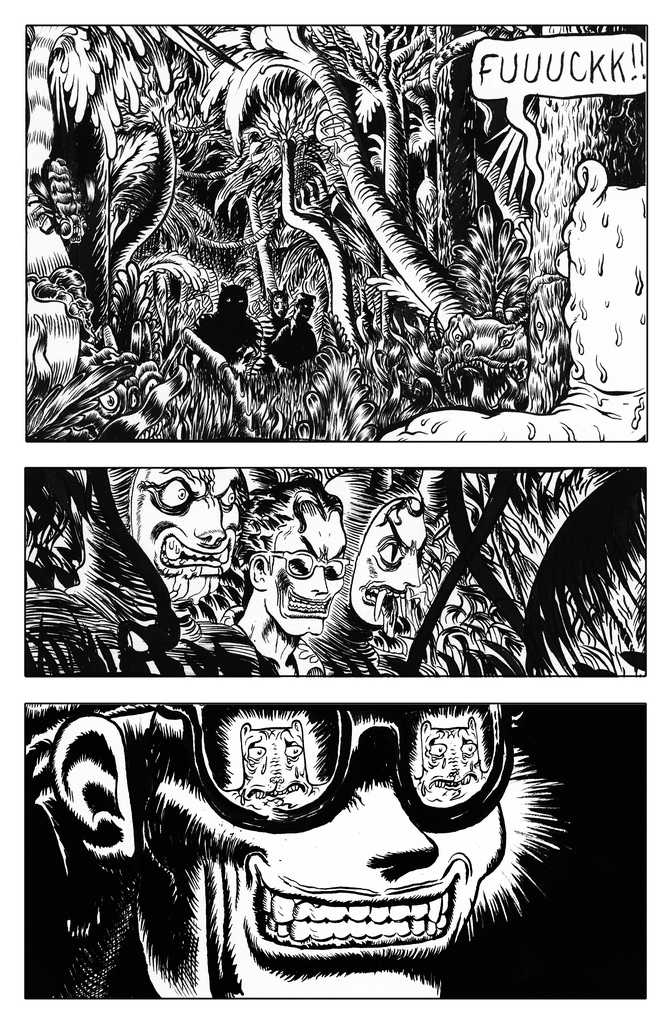

Comics Time: Demon God Goblin Heaven

February 22, 2012Demon God Goblin Heaven

Jesse Balmer, Jonny Negron, writers/artists

self-published, 2011

52 pages

$10

Read a preview at Jesse Balmer’s website

Watch a preview video on YouTube

Buy it from Secret Headquarters

This seamless collaboration between ADDXSTC 2011 Top Tenner Jonny Negron and his Chameleon co-editor Jesse Balmer mines a whole lot of gold from one simple plot vein: the reversal. Every time you get a handle on who’s the biggest shitheel or badass in the book, someone comes along to flip that on its head. Protagonist Charles of Charleston (Balmer’s signature character) is Patient Zero for this technique. The four-page preview sequence linked above was my first exposure to the book, and in the events it depicts the dividing line between victim and victimizer seemed almost painfully clear: Balmer’s goggle-eyed, fleshy, flabby, furrowed, nude, cat-like Charles — a character that seemingly sprung fully formed from the head of one of those grotesque John Kricfalusi close-ups of a smiling or grimacing Stimpy — was undoubtedly at the mercy of Negron’s leering, Wayfarer-sporting, brylcreem-coiffed, switchblade-toting antagonist and his thugs. (Thugs wearing old-timey one-piece swimming costumes and Balinese masks, no less.) But reading the comic itself reveals that Charles was the victimizer up until this point, a rampaging id that consumed or assaulted nearly everyone or everything in his path, including himself, until fate intervened in the form of larger, tougher hombres. The reversal gives the story juice, and reveals a versatility in Charles’ character design to boot: What seems vulnerable and tender in one set of circumstances comes across as priapistic and grotesque in another. The shades-sporting creep, as it turns out, is merely avenging the Casper-like ghost surfer Charles assaulted after washing up on a nearby beach, and is in turn outgunned and outclassed by a dog dressed like Solomon Kane and powered like Doctor Strange. Balmer and Negron’s art styles don’t seem like a natural fit beyond their mutual penchant for the grotesque — Negron’s eroticized coldness has little in common with Balmer’s thick vibrating inks — but in this book, a series of memorable characters doing memorable things in a blackly psychedelic environment, they make a happy match, and that yo-yo pacing is key.

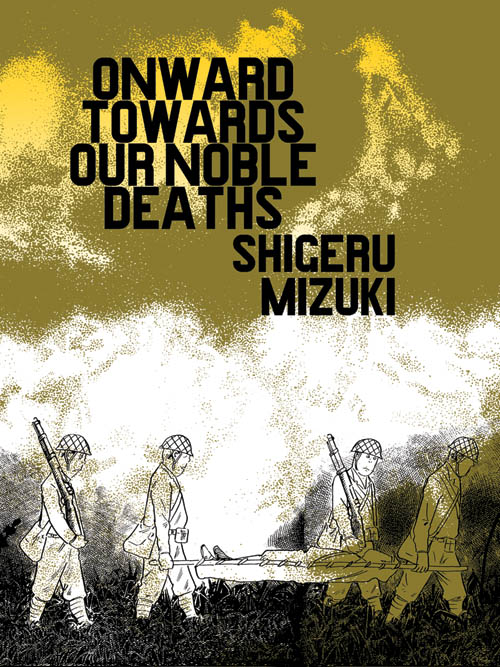

Comics Time: Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

February 20, 2012Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths

Shigeru Mizuki, writer/artist

Drawn and Quarterly, 2011

368 pages

$24.95

Buy it and read a preview from D&Q

Buy it from Amazon.com

Here’s a book with a hugely important message to which I am very sympathetic, which is never less than enjoyable to read or look at, which I nevertheless didn’t get a ton out of, in the end. A fictionalized memoir of Mizuki’s participation in the Japanese military’s ill-fated attempt to repel invading American forces from a South Pacific island, Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths alternates between expressively cartooned vignettes among the troops that show off Mizuki’s incongruously cute, oblong/oval-headed character designs — seriously, it’s like an army of Berts from Sesame Street — with powerful, passionately drawn photorealistic depictions of both the tropical island environment and the carnage it comes to house. Mizkuki’s disgust with the who-gives-a-fuck pointlessness of the men’s mission, and the callousness with which the commanding officers order the men into suicide runs when the mission inevitably fails, is palpable; interestingly, it comes through equally well in the black-comic cartoony material, which depict the forces’ slow attrition through disease, accidents, enemy forces, and even animal attacks, and in the astonishingly proficient hatching of the realistic scenes, wordless depictions of the island and the ocean and the spectral American G.I.s who bring death to them both. But the characters are more or less incidental to the book’s agenda — few of them are developed any more than is necessary to convey the idea that it was a waste to send this or that funny or annoying or brave or totally ordinary guy to his death for no reason — and thus the book can only get the emotional hooks required for that idea to connect into you in the abstract. If you already believe that war is hell, I’m not sure this book will enlighten you further, certainly not the way it did when it was initially released in Japan in the ’70s. But there’s one aspect that stuck out to me beyond the basics: The suicide-charge ethic of the Imperial Army comes across as a bizarre ideology simply grafted on top of an army full of regular guys, who complain and help each other out and badmouth the officers and make dirty jokes same as any other army, banzai or no. And in that sense, it makes you wonder what people half a world and half a century away from us will think of the ideologies that drove us to kill and die, too.

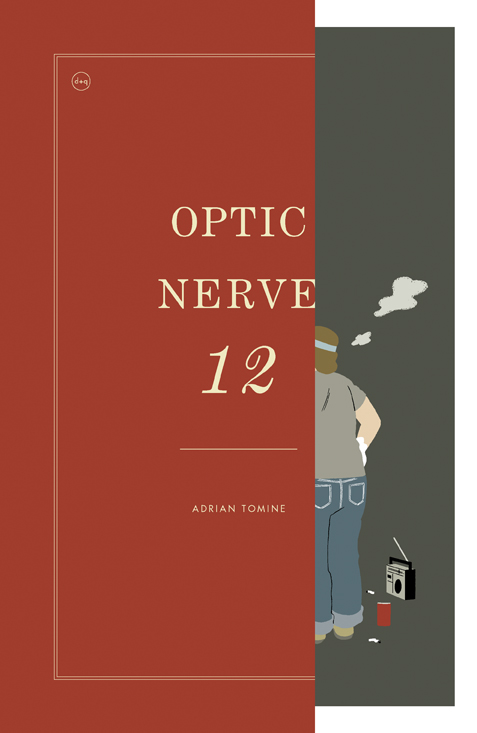

Comics Time: Optic Nerve #12

February 16, 2012Optic Nerve #12

Adrian Tomine, writer/artist

Drawn and Quarterly, 2011

40 pages

$5.95

Buy it from D&Q

Read a preview at Boing Boing

Man, is this thing ever happy to be a comic book.

The format of a comic doesn’t matter to me a whole lot, unless the format in question is notably detrimental to the comic it houses. I like the idea of serial alternative comic book series mostly for the promise of seeing a lot of work from alternative cartoonists on a regular basis, but today that need is met by the web. (Which can’t meet all needs, to be sure — it doesn’t meet the need of retailers to have that kind of material showing up fresh every few months and consequently attracting a different clientele to the shops on Wednesdays, but that’s not my bailiwick.) But in Optic Nerve #12, Adrian Tomine reminded me what can make an alt-comic such an attractive and pleasurable way of packaging material, something not even the most well-stocked RSS reader can provide.

In addition to the usual letters page, its weirdly personal mix of praise and criticism as po-facedly selected as always, the issue consists of three comics. The first, “Hortisculpture,” feels like an homage to the apparently final two issues of the greatest of the alternative comic books, arguably the two best single alternative comic book issues by anyone: Dan Clowes’s Eightball #22 and #23. Like them, the story is constructed from individual self-contained strips, in this case a full “week”‘s worth: six black-and-white four-panel strips plus a full-color “Sunday” page, over and over till the end of the story. Said story recounts a family-man landscaper’s quixotic career detour into the world of contemporary art via his own unique blend of sculpture and horticlture, an unappreciated (arguably unappreciatable) hybrid his pursuit of which upends his life. As a crypto-autobiography it’s a corker — a keyed-up, hyperreal representation of the travails of Tomine’s chosen form of self-imposed artistic marginalization. It’s as engrossing to watch him work his way through as, say, Gabrielle Bell’s similar fictionalizations of her family life. (Plus it allows Tomine’s customary preoccupation with the intersection of race and romance a new, markedly less hostile environment in which to flower.) Things have gone a lot better for the cartoonist than the hortisculptor, to be sure — the former just received some of the best notices of his career for the wide release of the comics he made about his marriage to the mother of his kid, while our last glimpse of the latter is of he and his daughter gleefully smashing his work to smithereens — but the anxieties underlying the worst-case-scenario comic are obviously real, and really funny. And once again like Clowes, in Eightball #22 and later in Wilson, Tomine’s working with a much “cartoonier” style — a curvier line, bulbous noses, dot eyes, doughier physiques — that enjoyably invokes similar work from Sammy Harkham or Chuck Forsman. It feels right, somehow, to look at art like this on a staple-bound page.

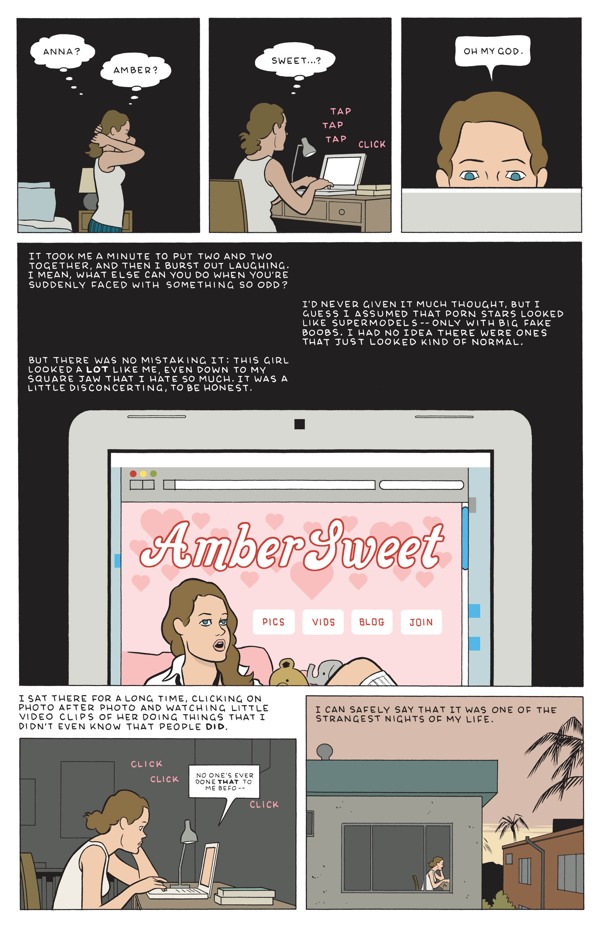

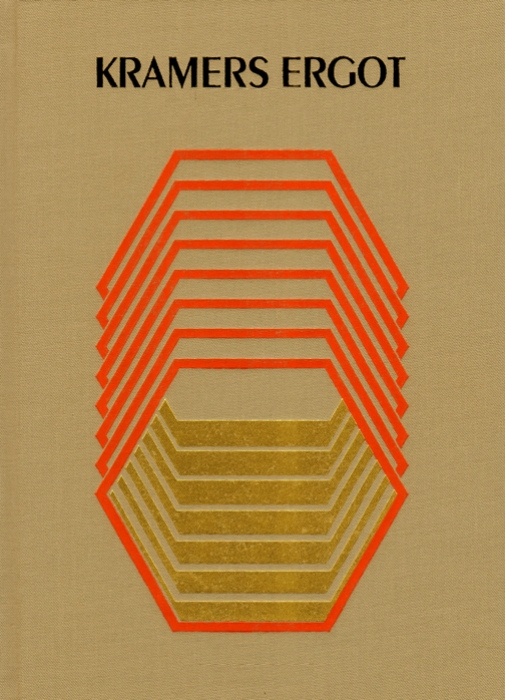

Next up is that staple of one-man anthology series, the reprint from some other anthology. In this case it’s Tomine’s “Amber Sweet” from the broadsheet-sized Kramers Ergot 7, attractively scaled down to the size of the floppy comic, its muted color scheme even more clearly centered around the nutmeg-colored hair of the young woman who discovers she’s the spitting image of the titular porn star. “Sweet” is fascinating to me in that it’s about how unsexy sex can be: our protagonist’s love life, and more besides, is basically destroyed by her resemblance to Amber, a resemblance the men in her life are either daunted by or way too into. Tomine’s perhaps uniquely suited to explore this plight: his cartooning is as sexy as it gets, I’ve always found — his line elegant, his compositions enticingly icy, his character designs very attractive, from Amber and her never-named doppelganger on down — but his work relentlessly cuts against that with the awkwardness and selfishness of his characters. Here we see a beautiful girl who looks like another beautiful girl who makes her living by taking her clothes off and having sex have sex herself as drawn by one of alternative comics’ great unsung sensualists, but the story denies us the pleasure on every possible level. It’s a blast to watch Tomine so successfully negotiate that obstacle course on the way to the story’s knockout ending, a beautiful and satisfying opening-up of the story’s emotional claustrophobia.

The third and final strip — two pages, 20-panel grids — is Tomine’s Lament, pretty much, a self-effacing mock-autobiographical strip about Tomine as “The Last Pamphleteer,” his adherence to the alt-comic format earning him the laughter of his peers and the indifference of his audience. And here, perhaps, he’s trying a little too hard. Throwing “tweet” into sneer quotes as if the term is an affectation instead of just, y’know, email or website; saying things like “I even liked it when the artist was obviously just trying to fill a few extra pages, and you’d get a pointless, dashed-off autobio strip or something!”, as if both he and we didn’t notice that he had to cram this thing onto the inside back cover to get it to fit; using D&Q publicist Peggy Burns as an antagonist, as if he weren’t still core Drawn and Quarterly artist Adrian Tomine; setting up Anders Nilsen and Kate Beaton as models for the new book-driven publishing model, as if they too weren’t primarily collecting work they published in smaller chunks elsewhere…He doth protest too much, and while the result is amusing, who needs it? He’s Adrian Tomine. He writes great and draws great and is as good at using his chosen format as anyone else is at using theirs. That’s all you need.

Comics Time: Kramers Ergot 8

January 18, 2012Kramers Ergot 8

Robert Beatty, Gabrielle Bell, Chris Cilla, Anya Davidson, Ron Embleton, C.F., Sammy Harkham, Tim Hensley, Kevin Huizenga, Ben Jones, Frederic Mullalley, Takeshi Murata, Gary Panter, Johnny Ryan, Leon Sadler, Frank Santoro, Dash Shaw, Ian Svenonius, writers/artists

Sammy Harkham, editor

PictureBox, January 2012

232 pages, hardcover

$32.95

Buy it from PictureBox

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

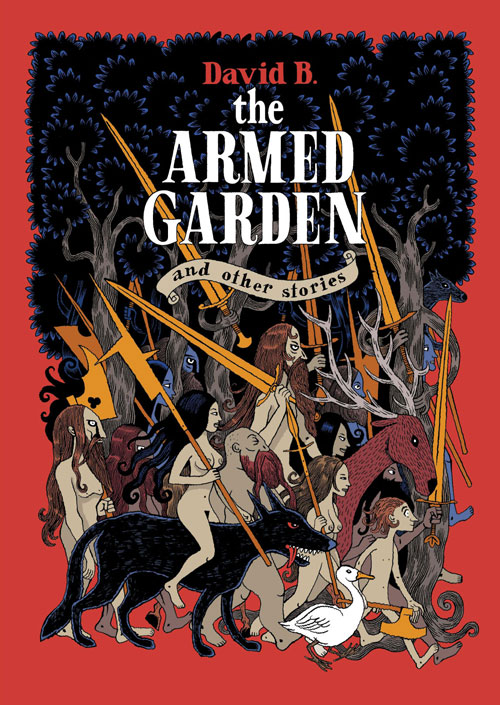

Comics Time: The Armed Garden and Other Stories

December 23, 2011The Armed Garden and Other Stories

David B., writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages, hardcover

$19.99

Read a 10-page preview and buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

About the only things impeding my completely unfettered enjoyment of and admiration for everything David B. achieves in The Armed Garden and Other Stories are familiarity — all three of the stories collected here appeared in the late, lamented Mome anthology at some point; and, because I am a morose and unpleasant person, the happy-ish ending — after a book of unremitting, near-ecstatic horror and slaughter, ending on a wistful up-note felt not so much unearned as simply unwanted.

But that’s it. Other than that, this collection is absolutely marvelous, a gorgeous and searing series of comics from an artist who earns the description “freakishly talented” as completely as anyone this side of his trans-Atlantic fellow in crafting dreamy/nightmarish parables of violent spirituality, Jim Woodring. These comics are just as lovely and just as frightening, and just as singularly the work of their creator and no other.

For one thing, they’re beyond gorgeous. B. has developed a form of expressionism that relies on curves rather than angles; simultaneously he’s fleshed out the stark intensity of his high-contrast black-and-white brush art with a lush duotone gold. The result is battle scenes that have the sharpness and savagery of a woodcut and the graphic simplicity of a Dark Ages tapestry, tied to prophetic visions and hedonistic reveries among the faithful peopled by characters you want to reach out and hug, so sensuous and inviting they seem. It’s almost unfair that the same guy who’s developed a visual language for battle that eloquently reduces its participants to interlocking graphic elements, a nigh-undifferentiated sea of swords, spears, grimaces, and gouts of blood, also maybe draws the sexiest pale naked women I’ve ever seen in a comic. But from a thematic perspective these stories are all about the way that religious fervor lends an air of all-consuming certainty and nobility to mankind’s most animalistic pursuits, from fucking to killing, so I suppose it’s only fitting.

Each of The Armed Garden‘s three stories — “The Veiled Prophet,” the title tale, and “The Drum Who Fell in Love” — is a transmission from the heightened reality of the legends surrounding various medieval religious cults, one from Arab Islam and two warring ones from European Christianity. As I mentioned when the first of these, “The Veiled Prophet,” hit our shores in Mome, they at first appear to all the world like an expressionistically drawn work of historical fiction, until the supernatural elements slowly take over. By focusing on the individual actors in each drama rather than the overall sweep of the history surrounding them, B. allows the reader to experience the awe and terror of divine/demonic intervention as a first-hand phenomenon; within the world of the stories, it’s as easy to swallow as are the more run of the mill sources of conflict with rival Popes and caliphs and so on. We get swept up in the madness and terror along with everyone else. And in all three cases, the fire of divinity burns too bright, consuming those who fan its flames. Provided you don’t buy its actual intervention in actual real life — and by situating each story within rejected, discredited cults, B. effectively removes the need to consider the more popular and lasting religions in this light — the message is clear: Belief in this shit, actualized into violence, will drive you as crazy and destroy you as completely as the real deal will. Gazing beneath the veil of the prophet, building your own paradise on earth, peering into the secrets of creation, communing with the dead, slaughtering out a path for God to tread — these things will kill you, blind you, drive you insane, leave you stranded with only the music of your mind for company. Ugly truths, presented as beautifully as is humanly possible.

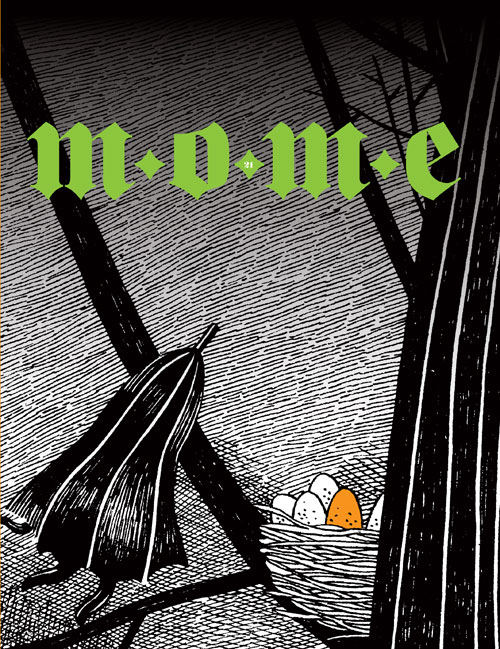

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 22: Fall 2011

December 20, 2011Mome Vol. 22: Fall 2011

Zak Sally, Kurt Wolfgang, Jordan Crane, Chuck Forsman, Steven Weissman, Sara Edward-Corbett, Laura Park, Tom Kaczynski, Joe Kimball, Jesse Moynihan, Josh Simmons, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Malachi Ward, Eleanor Davis, James Romberger, Derek Van Gieson, Michael Jada, Tim Lane, Nate Neal, Wendy Chin, Anders Nilsen, Tim Hensley, Lilli Carré, T. Edward Bak, Nick Drnaso, Joseph Lambert, Paul Hornschemeier, Sergio Ponchione, Nick Thorburn, Dash Shaw, Ted Stearn, Jim Rugg, Victor Kerlow, Noah Van Sciver, Gabrielle Bell, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, 2011

240 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

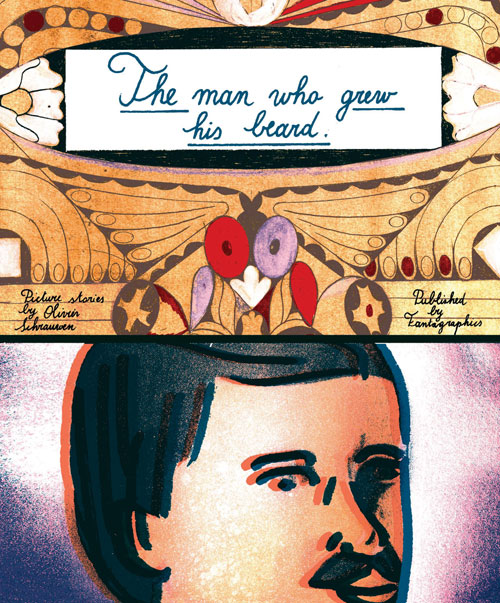

Comics Time: The Man Who Grew His Beard

December 19, 2011The Man Who Grew His Beard

Olivier Schrauwen, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

I love the disconnect between how big and broad this substantial softcover feels in your hands — at 8.5″ x 10.25 ” it’s just wider enough than your average graphic novel for you to notice it — and how tiny the little mustachioed men who people most of its stories feel on those big pages, even when they’re blown up big enough to occupy most of that real estate. It makes it feel even more alien than it already does, like you’re reading a giant’s minicomic.

I don’t know how he does it, whether it’s something to do with how he puts his lines down on paper or some treatment he gives them afterwards, but Flemish cartoonist Olivier Schrauwen makes images that look like…like they’ve been transmitted from a great distance, both temporally and spatially. He’s playing with style and design that looks like it predates the Great War, and his line and coloring has a hazy feel to it that could be a copy of a copy of a copy, or the unlikely discovery of some microscopic cartooning culture blown up to many times its original size. There’s something off about it just as surely as there’s something off about Al Columbia’s rotted vintage visuals, only here that off-ness is used in service of a comic surrealism rather than a horrific one. He can stick it to the foibles of the 19th-century culture whose style he’s swiping quite effectively — savagely satirizing Belgium’s bloody misadventures in Africa, parodying the West’s penchant for physiognometric pseudoscience with a look at what your hairstyle says about your mental capacity, lampooning the world-conquering bravado of transcontinental rail, and so on. But he’s just as likely to seize upon some strange effect or idea and run with it as hard and as fast as he can — nearly literally, in once case, in a strip consisting more or less solely of a guy running to catch a train for as long and as far as the train would have taken him to begin with. Elsewhere, he shatters sexual idylls into a fractal feedback loop or draws its participants as lounging subjects of some kind of weird cubist stained-glass art style; portrays a man who can paint things into existence by trotting him through a series of guffaw-inducing mock-heroic poses, as if his miraculous creative abilities were only secondary proof of his awesomeness compared to his theatrical, bare-chested machismo; and uses bright color and titanically ornate architecture against bland ones to paint a portrait of a catatonic man’s rich and adventurous interior life of fun with a beautiful woman and a beloved child, in a story that ended up being actually quite moving. These are deeply strange short stories, centered on ideas and effects I’m not sure I’d have come up with even with the proverbial infinite number of monkeys at my disposal; even in this short-story-saturated alternative comics climate, there’s nothing else like his gestalt of finely calibrated nonsense. It’s good to see that comics can do things you’d never think to ask of them in the first place.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 21: Winter 2011

December 16, 2011Mome Vol. 21: Winter 2011

Sergio Ponchione, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Josh Simmons, Dash Shaw, Steven Weissman, Kurt Wolfgang, Sara Edward-Corbett, Nicolas Mahler, Tom Kaczynski,

Josh Simmons, Jon Adams, Nate Neal, T. Edward Bak, Michael Jada, Derek Van Gieson, Nick Thorburn, Lilli Carré, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, 2011

112 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

It was the best of Momes, it was the worst of Momes. Alright, that’s not quite accurate, and not quite fair, either. But this unwittingly penultimate issue of Fantagraphics’ long-running alternative-comics anthology — page for page the longest-running such enterprise in American history! — is a hit-or-miss affair in the mighty Mome manner. In the miss column you can place Sergio Ponchione’s bombastic, cartoony fantasy about an imaginary childhood friend brought to life; there’s really not much more to it than that description would indicate. Ditto Kurt Wolfgang’s next “Nothing Eve” chapter, which continues to work the “people still act pretty much the same even though the end of the world is coming” buttons it’s been mashing since issue #1. T. Edward Bak’s “Wild Man” remains awkwardly paced due to its split-up narrative captions; Nicolas Mahler’s autobio strip remains of limited interest to people not Nicolas Mahler; Lilli Carré’s contribution is nicely colored in reds and blues but otherwise insubstantial.

A few contributions are both hit and miss at once. Sara Edward-Corbett’s near-wordless reverie involving inanimate objects romping around the outside of a house comes across more inscrutable than mysterious, but at the same time her crosshatching and linework are an absolute marvel, and she’s playing with forms (and with form) in a fashion reminiscent of John Hankiewicz, if not as successful. Steven Weissman’s deadpan “Barack Hussein Obama” strips fall flat when they merely parody the rhythms of four-panel gag comics, but spring to surreal and oddly scathing life when he injects a healthy dose of the sinister supernatural into them. I’ve never quite cottoned to the way Jon Adams’s razor-thin line and labored-over character renderings sit against the large white expanses of his pages, and his writing feels overwrought to me, but he does give his blackly humorous tale of a hunting expedition gone bad a laugh-out-loud visual punchline. And Nate Neal’s caveman morality play makes much better use of his meaty cartooning than his lukewarm slice-of-lifers do, though the conceit of gibberish dialogue from the cavepeople conceals more than it illuminates.

So that leaves the hits, and they’re strong enough to make the book worth checking out. Dash Shaw continues his seemingly ongoing series of adaptations of “reality” programming, this time an excerpt from a making-of documentary about Jurassic Park; he has a really sharp and off-kilter eye for people observing and commenting on their own behavior for a camera, and his transition from talking heads to full documentary “footage” is a gleeful one. Nick Thorburn’s take on Benjamin Franklin, a first-person monologue in which Ben lets us in on a dirty little secret, is anachronistically absurd (“In Seventeen-Sumthin’-Er-Other, right before I invented electricity and just after I’d sired my illegitimate son, I received an e-mail from Lord Sandwich about comin’ to London to take part in this new secret society known as ‘The Hellfire Club.'”) and very funny, with a great undergroundy character design for Franklin himself. Derek Van Gieson’s murky World War II period piece continues to stun from page to page. Tom Kaczynski examines home ownership during terminal-stage capitalism as only he can, casting it as a catalyst for powerful erotic and apocalyptic impulses and proving himself once again to be one of the most stealthily sexy cartoonists working today. “Stealthy” isn’t a word I’d use for Josh Simmons, but he doesn’t need it: His weird psychedelic fantasia on racism “The White Rhinoceros” is as bold and bulldozing as the giant slugs who stampede across its pages, and the elliptically concluded short story “Mutant” ends with an image of an enraged creature in the form of a human female, her nude body shadowed but covered in glistening sweat, that may as well symbolize the workings of Simmons’s entire brain. You gotta take the rough to find the diamonds.

Comics Time: Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot

December 15, 2011Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot

Jacques Tardi, writer/artist

Adapted from the novel by Jean-Patrick Manchette

Fantagraphics, 2011

104 pages, hardcover

$18.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Fantagraphics keeps churning out lovely translated editions of the work of French comics master Jacques Tardi at a truly admirable clip. This is the fourth in what I would consider the “main” Tardi/Fanta line of slim hardcovers, distinguished by no-nonsense Adam Grano cover designs that juxtapose key sequences from Tardi’s ink-soaked black-and-white interior art with bold slashes of color and block-caps for title and credit information. If there’s a better mesh of form and function in comics right now this side of, well, Fanta’s similarly designed Love and Rockets digests, I’d sure love to see it. In much the same vein as Tardi’s previously released adaptation of a crime novel by author Jean-Patrick Manchette, West Coast Blues, Like a Sniper Lining Up His Shot is a grimly economical story of a man on the run from killers, with bursts of violence that slash in out of nowhere. In other words, you can judge a book by its cover.

The two books have much in common beyond their common language of men hunted by hitmen across the length and breadth of France. Both protagonists are bizarrely taciturn about their predicaments, almost to the point where you’re left to wonder if there’s some sort of mental disability involved. Sniper‘s Martin Terrier (great name) at least has the excuse of being a mercenary and assassin to explain his flat affect where killing’s concerned, as opposed to West Coast Blues‘ wrong-man family-guy George. But he more than makes up for this in his personal life, a disaster area predicated entirely on his deeply weird belief that the women with whom he involves himself can switch their affections for him on and off after years of one setting or the other based solely on his say-so. The woman for whom he “risks it all” — Tardi and Manchette’s interpretation of this trope ladles those sneer quotes all over it — is an equally weird and unpleasant character, ricocheting from emotion to emotion when Terrier’s intrusion into the life she’d been leading without him violently upends her status quo, until finally settling on some weird sneering sex-hungry brand of derision for him and his life of crime and adventure.

In all honesty, these emotional and behavioral patterns are so difficult to recognize even when allowing for the remove between a hired gun and a comics critic that they get in the way of Tardi and Manchette’s underlying indictment of society’s casual savagery, and its propensity for covering up that savagery with bullshit that pins it on The Other Side. But upon reflection, I wonder if these terrible people’s wholly alien way of interacting with the world isn’t just the writing equivalent of Tardi’s nimble, scribbled line and sooty blacks — a heightened reality in which things are rendered at their loosest, darkest, ugliest, and weirdest at all times. God knows both creators can rigorously focus when they want: Manchette squeezes a quite believable custody battle between Terrier and his now-ex girlfriend over a beloved cat into the proceedings, while Tardi’s backgrounds and lighting effects are a realist’s dream and his action sequences and set-pieces are choreographed tighter than a drum. The absurdist demeanors may prevent everything from gelling as well as they might have done, but overall the book delivers a fastball to your face so hard that you barely have time to notice that some of the stitches need straightening.

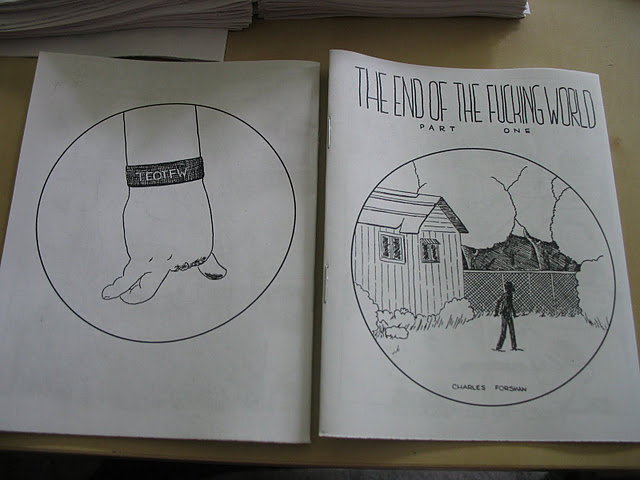

Comics Time: The End of the Fucking World Part One

December 9, 2011The End of the Fucking World Part One

Chuck Forsman, writer/artist

self-published, December 2011

12 pages

$1

Buy it from Oily Boutique

How’s that for a title? And I’m pleased to say the contents are just as good. Forsman has become a must-read talent for me; each new minicomic shows growth. He’s a cartoonist of great restraint, in terms of both visuals (this is all slight, feathery lines and quiet, flat-affect “acting” from the characters) and pacing (this is all no-nonsense page-long vignettes, with dialogue and captions strategically deployed for a steady beat-beat-beat rhythm). His characters themselves feel considered and lived-in. The lead character here is a believably blasé creep recounting his childhood, marked by killing animals, mutilating himself, and discovering his inability to feel love or have a sense of humor. But thanks to a terrific hesher character design, his evident sociopathy come across not like some heavy-handed depiction of a budding Ted Bundy but like a satire of run-of-the-mill teenage-dirtbag-ism. He’s like Beavis Bateman.

These two potentially opposing views of our hero come together in the story’s centerpiece, the four pages dedicated to his going-through-the-motions relationship as a 16-year-old with his pretty, forward girlfriend Alyssa. It’s easy to see how his aloofness could come across as attractive, and the resulting, detailed depiction of skewed adolescent sexuality is as skeevy and funny and sexy and creepy as they come. He fantasizes about strangling her as she tells him “God, I want you” takes off her shirt; their tongues intertwine like snakes on a caduceus; he presses his face to the convex arc of her stomach as she presses his head down toward her underwear; they have the following amazing exchange as they snuggle on the couch watching TV:

“Have you ever eaten a pussy before?”

“Sure.”

“I want you to eat mine.”

“Right now?”

The awkwardness, the urgency, the sense of discovery, the sense of revulsion — it’s all true, even if you’ve never stuck your own hand in a garbage disposal on purpose or crushed a stray cat with a stone. Where those aspects of the story will take us is something I’m greatly looking forward to seeing in future issues, given where we’ve gone here.