Posts Tagged ‘Lisa Hanawalt’

Eat This Book: ‘BoJack Horseman’ Artist Lisa Hanawalt Takes Her ‘Hot Dog Taste Test’

June 16, 2016I had the impression going in that this is “Lisa Hanawalt’s Food Book,” but having read it’s like your real subject is how it feels to inhabit a physical body. The food angle is just there to whet your appetite. So to speak.

You totally found me out. This book is an edible Trojan horse? But yes, it could have been called Here’s a Pile of Stuff Lisa Felt Like Making Over the Last Few Years and Most of It Is Related to Food, but people tend to want a tighter concept before committing to reading an entire book.

[…]

One aspect of physicality it doesn’t address much is sex. There are a couple of allusions, and a lot of sex-adjacent body parts, but it’s much more about eating, shitting, peeing, menstruating, traveling, riding, feeling full, getting sick…

That’s a good point, because I haven’t been one to shy away from sex in the past. Maybe it’s a subconscious attempt at making something sliiiightly less creepy, and to let people dig for my hornier work if they’re true fans? Maybe I’m just going through a bowel phase, the way Picasso had a blue period? I’m also a little grossed out when food and sex are combined, honestly.

Comics Time: Coyote Doggirl and Nux Yorica

October 16, 2013Recently I reviewed Coyote Doggirl by Lisa Hanawalt and Nux Yorica by Cameron Hawkey for Vorpalizer. It’s really remarkable how much strong artcomics work is being made without ever needing touch a single paper page to read it.

The 20 Best Comics of 2011

January 1, 201220. Uncanny X-Force (Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña, Marvel): In a year when the ugliness of the superhero comics business became harder than ever to ignore, it’s fitting that the best superhero comic is about the ugliness of being a superhero. Remender uses the inherent excess of the X-men’s most extreme team to tell a tale of how solving problems through violence in fact solves nothing at all. (It has this in common with most of the best superhero comics of the past decade: Morrison/Quitely/etc. New X-Men, Bendis/Maleev Daredevil, Brubaker/Epting/etc. Captain America, Mignola/Arcudi/Fegredo/Davis Hellboy/BPRD, Kirkman/Walker/Ottley Invincible, Lewis/Leon The Winter Men…) Opeña’s Euro-cosmic art and Dean White’s twilit color palette (the great unifier for fill-in artists on the title) could handle Remender’s apocalyptic continuity mining easily, but it was in silent reflection on the weight of all this death that they were truly uncanny.

19. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969 (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, Top Shelf/Knockabout): I’ll admit I’m somewhat surprised to be listing this here; I’ve always enjoyed this last surviving outpost of Moore’s comics career but never thought I loved it. But in this installment, Moore and O’Neill’s intrepid heroes — who’ve previously overcome Professor Moriarty, Fu Manchu, and the Martian war machine — finally succumb to their own excesses and jealousies in Swinging London, allowing a sneering occult villain to tear them apart with almost casual ease. It’s nasty, ugly, and sad, and it’s sticking with me like Moore’s best work.

18. The comics of Lisa Hanawalt (various publishers): As I put it when I saw her drawing of some kind of tree-dwelling primate wearing a multicolored hat made of three human skulls stacked on top of one another, Lisa Hanawalt has a strange imagination. And it’s a totally unpredictable one, which is what makes her comics – whether they’re reasonably straightforward movie lampoons or the extravagantly bizarre sex comic she contributed to Michael DeForge and Ryan Sands’s Thickness anthology, as dark and damp as the soil in which its earthworm ingénue must live – a highlight of any given day a new one pops up.

17. Daybreak (Brian Ralph, Drawn and Quarterly): Fort Thunder’s single most accessible offspring also proves to be its bleakest, thanks to an extended collected edition that converts a rollicking first-person zombie/post-apocalypse thriller into a troubling meditation on the power of the gaze. Future artcomics takes on this subgenre have a high bar to clear.

16. Habibi (Craig Thompson, Pantheon): It’s undermined by its central characters, who exist mainly as a hanger on which this violent, erotic, conflicted, curious, complex, endlessly inventive coat of many colors is hung. But as a pure riot of creative energy from an artist unafraid to wrestle with his demons even if the demons end up winning in the end, Habibi lives up to its ambitions as a personal epic. You could dive into its shifting sands and come up with something different every time.

15. Ganges #4 (Kevin Huizenga, Coconino/Fantagraphics): Huizenga wrings a second great book out of his everyman character’s insomnia. It’s quite simple how, really: He makes comics about things you’d never thought comics could be about, by doing things you never thought comics could do to show you them. Best of all, there’s still the sense that his best work is ahead of him, waiting like dawn in the distance.

14. The Congress of the Animals (Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics): The potential for change explored by the hapless Manhog in last year’s Weathercraft is actualized by the meandering mischief-maker Frank this time around. While I didn’t quite connect with Frank’s travails as deeply as I did with Manhog’s, the payoff still feels like a weight has been lifted from Woodring’s strange world, while the route he takes to get there is illustrated so beautifully it’s almost superhuman. It’s the happy ending he’s spent most of his career earning.

13. Mister Wonderful (Daniel Clowes, Pantheon): Speaking of happy endings an altcomix luminary has spent most of his career earning! Clowes’s contribution to the late, largely unlamented Funny Pages section of The New York Times Magazine is briefly expanded and thoroughly improved in this collected edition. Clowes reformats the broadsheet pages into landscape strips, eases off the punchlines and cliffhangers, blows individual images up to heretofore unseen scales, and walks us through a self-sabotaging doofus’s shitty night into a brighter tomorrow.

12. The comics of Gabrielle Bell (various publishers): Bell is mastering the autobiography genre; her deadpan character designs and body language make everything she says so easy to buy – not that that would be a challenge with comics as insightful as her journey into nerd culture’s beating heart, San Diego Diary, just by way of a for instance. But she’s also reinventing the autobiography genre, by sliding seamlessly into fictionalized distortions of it; her black-strewn images give a somber, thoughtful weight to any flight of fancy she throws at us. What a performance, all year long.

11. The Armed Garden and Other Stories (David B., Fantagraphics): Religious fundamentalism is a dreary, oppressive constant in its ability to bend sexuality to mania and hammer lives into weapons devoted to killing. But it has worn a thousand faces in a millennia-long carnevale procession of war and weirdness, and David B. paints portraits of three of its masks with bloody brilliance. Focusing on long-forgotten heresies and treating the most outlandish legends about them as fact, B.’s high-contrast linework sets them all alight with their own incandescent madness.

10. Too Dark to See (Julia Gfrörer, Thuban Press): It was a dark year for comics, at least for the comics that moved me the most. And no one harnessed that darkness to relatable, emotional effect better than Julia Gfrörer. Her very contemporary take on the legend of the succubus was frank and explicit in its treatment of sexuality, rigorously well-observed in its cataloguing of the spirit-sapping modern-day indignities that can feed depression and destroy relationships, and delicately, almost tenderly drawn. It’s like she held her finger to the air, sensed all the things that can make life rotten, and cast them onto the pages. She made something quite beautiful out of all that ugly.

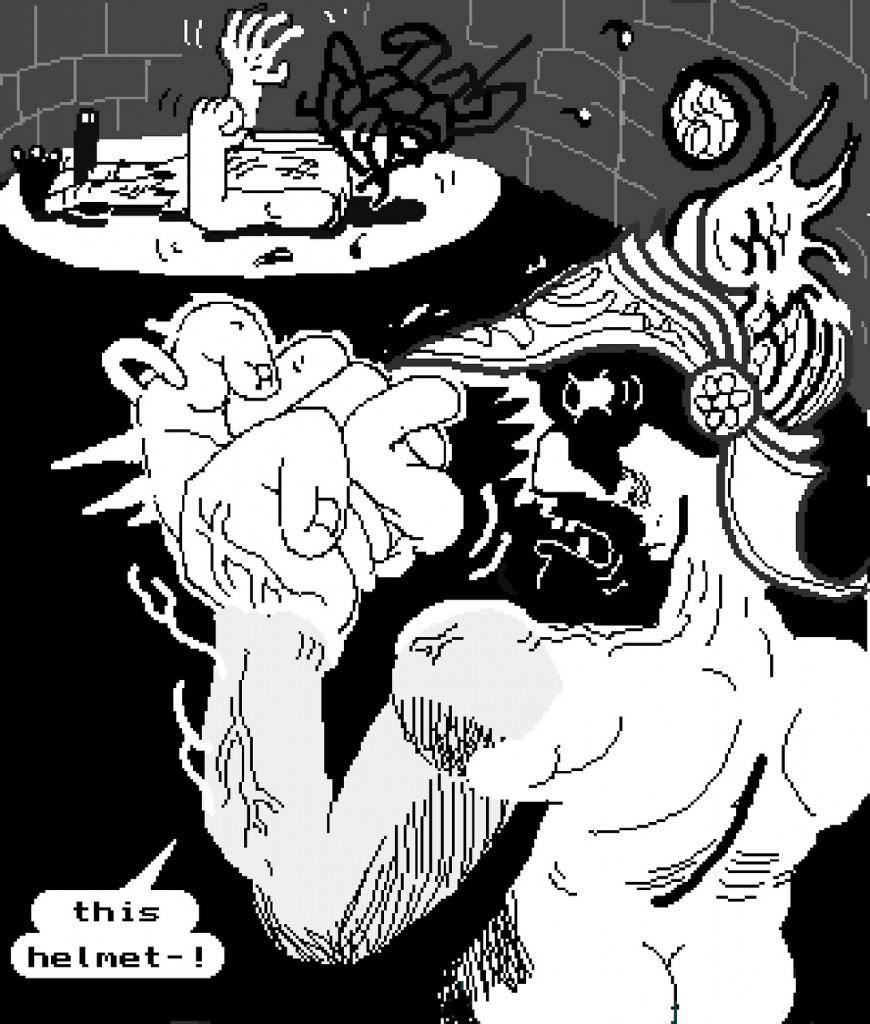

9. The comics and pixel art of Uno Moralez (self-published on the web at unomoralez.com): What if an 8-bit NES cut-scene could kill? The digital artwork of Uno Moralez — some of it standard illustrations, some of it animated gifs, some of it full-fledged comics — shares its aesthetic with The Ring‘s videotape or Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie: a horror so cosmically black, images so unbearably wrong, that they appear to have leaked into and corrupted their very medium of transmission. Moralez fuses crosses the streams of supernatural trash from a variety of cultures — the legends and Soviet art of his native Russia, the horror and porn manga of Japan, the B-movies and horror stories of the States, the formless sensation aesthetic of the Internet itself — into a series of images that is impossible to predict in its weirdness but totally unflagging in its sense that you’d be better off if you’d never laid eyes on it. I can’t wait to see more.

8. The comics of Michael DeForge (various publishers): The last time you saw a cartoonist this good and this unique this young, you were probably reading the UT Austin student newspaper comics section and stumbling across a guy named Chris Ware. All four of DeForge’s best-ever comics — his divorced dad story in Lose #3, his shape-shifting/gender-bending erotica in Thickness #2, his self-published art-world fantasia Open Country, and his gorgeously colored body-horror webcomic Ant Comic — came out this year, none of them looking anything at all like anything you could picture before seeing your first Michael DeForge comic. It’s almost frightening to think where he’ll be five years from now, ten years from now…or even just this time next year.

7. The comics and art of Jonny Negron (various publishers): What if someone took Christina Hendricks’s walk across the parking lot and trip to the bathroom in Drive and made an entire comics career out of them? That is an enormously facile and reductive way to describe the disturbing, stylish, sexy, singular work of Jonny Negron, the breakout cartoonist of the year, but it at least points you in the right direction. No one’s ever thought to combine his muscular yet curiously dispassionate bullet-time approach to action and violence, his Yokoyama-esque spatial geometry, his attention to retrofuturistic fashion and style, his obvious love of the female body in all its shapes and sizes, and his ambient Lynchian terror; even if they had, it’d be tough to conceive of anyone building up his remarkable body of work in such a short period of time. Open up your Tumblr dashboard or crack an anthology (Thickness, Mould Map, Study Group, Smoke Signal, Negron and Jesse Balmer’s own Chameleon), and chances are good that Negron was the weirdest, best, most coldly beautiful thing in it. It’s like a raw, pure transmission from a fascinating brain.

6. The Wolf (Tom Neely, I Will Destroy You): Neely’s wordless, painted, at-times pornographic graphic novel feels like the successful final draft to various other prestigious projects’ false starts. It’s a far less didactic, more genuinely erotic attempt at high-art smut than Dave McKean’s Celluloid; a less self-conscious, more direct attempt at frankly depicting both the destructive and creative effects of sex on a relationship via symbolism than Craig Thompson’s Habibi; a blend of sex and horror and narrative and visual poetry and ugly shit and a happy ending that succeeds in each of these things where many comics choose to focus on only one or two.

5. The Cardboard Valise (Ben Katchor, Pantheon): Prep your time capsules, folks: You’d be hard pressed to find an artifact that better conveys our national predicament than Ben Katchor’s latest comic-strip collection, a series of intertwined vignettes created largely before the Great Recession and our political class’s utter failure to adequately address it, but which nonetheless appears to anticipate it. Its message — that blind nationalism is the prestige of the magic trick used by hucksters to financially and culturally ruin societies for their own profit — is delightfully easy to miss amid Katchor’s remarkable depictions of lost fads, trends, jobs, tourist attractions, and other detritus of the dying American Century. He’s the very most funnest Cassandra around.

4. Love from the Shadows (Gilbert Hernandez, Fantagraphics): I picture Gilbert Hernandez approaching his drawing board these days like Lawrence of Arabia approaching a Turkish convoy: “NO PRISONERS! NO PRISONERS!” In a year suffused with comics funneling pitch-black darkness through a combination of sex and horror, none were blacker, sexier, or more horrific than this gender-bending exploitation flick from Beto’s “Fritz-verse.” None also functioned as a rejection of the work that made its creator famous like this one did, either. Not a crowd-pleaser like his brother, but every bit as brilliant, every bit as fearless.

3. Garden (Yuichi Yokoyama, PictureBox): Like a theme park ride in comics form — with the strange events it chronicles themselves resembling a theme park ride — Yokoyama’s book is a breathtaking, breathless experience. Alongside his anonymous but extravagantly costumed non-characters, we simply go along for the ride, exploring Yokoyama’s prodigious, mysterious imagination as he concocts a seemingly endless stream of increasingly strange interfaces between man and machine, nature and artifice. As a metaphor for our increasingly out-of-control modern life it’s tough to top. As pure thrilling kinetic cartooning it’s equally tough to top.

2. Big Questions (Anders Nilsen, Drawn & Quarterly): Last year, I wrote that if the collected edition of Nilsen’s long-running parable of philosophically minded birds and the plane crash that turns their lives upside-down didn’t top my list whenever it came out, it must have been some kind of miracle year. Turns out that it was. But you’d pretty much have to create a flawless capstone to a thirty-year storyline of neer-peerless intelligence and artistry to top this colossal achievement. Nilsen’s painstaking, pointillist cartooning and ruthless examination of just how little regard the workings of the world have for any given life, human or otherwise, marks him as the best comics artist of his generation, and solidifies Big Questions‘ claim as the finest “funny animal” comic since Maus.

1. Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 (Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Fantagraphics): Gilbert got his due elsewhere on my list, so let’s ignore his contribution to this issue, which advance the saga of his bosomy, frequently abused protagonist Fritz Martinez both on and off the sleazy silver screen. Instead, let’s add to the chorus praising Jaime’s “The Love Bunglers” as one of the greatest comics of all time, the point toward which one of the greatest comics series of all time has been hurtling for thirty years. In a single two-page spread Jaime nearly crushes both his lovable, walking-disaster main characters Maggie and Ray with the accumulated weight of all their decades of life, before emerging from beneath it like Spider-Man pushing up from out of that Ditko machinery. You can count the number of cartoonists able to wed style to substance, form to function, this seamlessly on one hand with fingers to spare. A masterpiece.

Comics Time: Thickness #2

October 17, 2011Thickness #2

Angie Wang, Lisa Hanawalt, Michael DeForge, Mickey Zacchilli, Brandon Graham, True Chubbo, Jillian Tamaki, writers/artists

Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge, editors

self-published, October 2011

60 pages

$12

Buy it from the Thickness website

Anthology of the year? I’d need to double-check some release dates, but it certainly seems that way to me. The second installment of Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge’s art-smut comics series is an intense, diverse collection of sex comics, beautifully printed and rich enough to revisit well after your first virgin read.

Michael DeForge, god help us all, continues his juggernaut run with what could well be his best comic yet. “College Girl by Night” stars a young man who’s transformed by the light of the full moon into a beautiful young woman, and uses the time to seduce and fuck college boys. His/her narrative captions don’t comment on the night-in-the-life activities depicted in the art, but rather explain the background of the transformations, her preferred conquests (tired of her “spoiled, drunken nineteen-year-olds,” she’s “made vague plans to set my sights on Edgeton professors, posing a student seeking advice after hours”), her almost idle questions about the science of it all (“Maybe if I got pregnant, it would only show when I transformed. If I even have a uterus, that is”), fictional precedents (“When Billy changed into Captain Marvel he wasn’t technically ‘transforming’…he was having his Billy Batson body physically replaced with an entirely different Captain Marvel one”), and daydreams about starting a relationship while in female form (“I once found a Missed Connection written about me on Craigslist”). It’s funny stuff, featuring DeForge’s trademark juxtaposition of the fantastic and the mundane. But it’s also really, really hot stuff. His character design for the main character’s female form is a note-perfect assemblage of alluring details: spagetti-like tendrils of hair, a dusting of freckles, a short and nearly translucent dress, long lashes that flutter when she throws her mouth open in ecstasy. But then DeForge takes the ruthlessly (if ironically) heterosexual nature of the situation (as she herself puts it, “Is it hugely unimaginative that during my time as a woman, the only activities I’ve done so far is fuck myself or get fucked?”) and crashes it right into its own subtext, reversing the transformation mid-coitus and presenting the two college guys now present on the scene with the opportunity to pick up where they left off, or not. Even if your door doesn’t swing in that direction, there’s a willingness to be led solely by pleasure and desire, a “Shhhh–no one can see, so why not?” quality, that’s hard to deny.

Brandon Graham’s “Dirty Deeds” is the most lighthearted of the contributions (well, aside from True Chubbo’s), and his sense of humor isn’t mine. It’s got this bigfooted vaudevillian underground schtickiness to it that’s just not my thing unless it’s Marc Bell. (Lots and lots of puns: “prostate of shock,” “cervix with a smile,” “I was young, I needed the monkey” — that last one’s a bit of a long story.) But that’s not to say that a breezy sex romp isn’t a welcome addition to this issue’s 31 flavors. Certainly Graham’s warm, curving line is shiny and happy enough to make up for a few jokes that leave me cold, and it’s fascinating watching him use it to achieve certain unique effects — the way he crams detail into limited segments of the page, piling line on line like a soft-serve ice cream cone, while letting the rest of the page breathe, say, which in turn lets him work wonders with images of massive science-fictional scale. And he really makes the most of Sands’s red-orange risograph’d coloring, particularly with his vivacious heroine’s hair and a sexy tan-line effect using what looks like the world’s tiniest zipatone dots. I’m kind of amazed that anything would give this Adrian Tomine print a run for its money in the “Sexiest Use of Tanlines 2011” sweepstakes, but there you have it.

Mickey Zacchilli’s contribution is the most off-model of the bunch, a melancholy affair in which a Brian Chippendalesque lost girl loses her wedding ring and therefore enters some weird subterranean sex chamber, in which a brawny beast and a “slime worm” have their way with her as she worries about other things. What keeps her going is the promise of ice cream on the other side of the chamber, but the showstopping reverie begins with the phrase “All I could think about at that moment were all the various objects that I had never stuck in my vagina.” Arrayed in the closest thing to a clinical grid as Zacchilli’s noisy, scratchy line can muster, this assortment goes from “Yeah, okay, feasible for a curious young woman” (“screwdriver,” “chisel tip Sharpie permanent marker”) to “uh-oh” (“rawhide dog bone,” “rotting arm,” “disembodied head”). When added to the brusque treatment she receives from the creature who lets her in — “Thru the door Alice, Jeanette, Angie, whatever” he says, her identity unimportant — and her tears when she discovers the ice cream shop is closed, it makes for a distressing portrait of disconnect between mind and body, thought and deed.

Dare I call Angie Wang’s contribution erotica rather than smut? Wang offers a four-page start-to-finish portrait of two women — one seemingly shy or hesitant, the other taking charge — having sex. Each panel depicts a discrete body part or moment of connection. It’s a familiar panoptic effect for this kind of thing, and I usually find it to be a bit false to the experience of sex, presenting it as a sort of greatest-hits grab bag rather than a journey from start to finish where the momentum, the upping of the ante from moment to moment, is key. But Wang cleverly jettisons the mishmash approach with an array of techniques: ratcheting the panel grid back from page to page, from 16 to 9 to 4 to a final, climactic (pun intended) splash page; using tangents to connect one panel to the next; paring away dialogue and sound as she goes; altering the focus of each page, from foreplay to initial genital contact to climax to afterglow. Whether despite or because of its delicate, painterly line, it’s got oomph.

Lisa Hanawalt’s contribution is profoundly Hanawaltian. Using the tried-and-true porn setup of the teacher with the hot student, she subverts (or heightens, depending on what you’re into) the fantasy by having the pair’s taboo rendez-vous take place in full view of the rest of the class; the teacher doesn’t even stop delivering his lesson on unreliable narrators (“the narrator makes mistakes” he says as he unzips his fly). Hanawalt apes the male focus on individual body parts with alarming accuracy: “Oh god, her tits! Tiiiiiits…And that ASS,” thinks the teacher over a series of panels focusing on the student’s curves with that familiar combination of thumbs-up celebration and lizard-brain leer. Oh, did I mention she short-circuits the whole thing by giving the girl the featureless conical head of a worm while stuffing her cleavage with fibrous miniature worms, and by giving the bird-headed teacher a penis that itself ends in a bird’s head, which literally vomits its semen all over her ass and vagina when he pulls out? When she slaps a David Lee Roth-referencing “CLASS DISMISSED!” on the final panel, I’m not sure whether to run for the door or stay for extra credit.

The final two contributions hearken back to Sands’s zine roots: Ray Sohn and his anonymous wife serve up one of the funniest, grossest True Chubbo strips to date (you’ll love the Lawrence of Arabia “NO PRISONERS!” quote, especially once you see the context in which it’s being quoted), while Jillian Tamaki’s centerfold pinup intrigues with its incongruous details — a monumental topless woman kneels amid lush flowers and a small army of Russian doll-like people-shaped dildos (I think?), her implacable gaze juxtaposed with her very human bikini-area stubble and a big goofy digital watch on her wrist. They give Thickness #2 a welcome diversity of form as well as content, a “hey, here’s everything that was fit to print” feel.

Thickness #2 is the real deal: talented, fearless cartoonists working in that viscous red zone of pleasure, terror, filth, and fun where the only thing that matters is what the body does and doesn’t want, and your brain is simply forced to go along for the ride. Bravo, thumbs up, panties down.

Comics Time: Prison for Bitches

June 10, 2011Prison for Bitches

Ryan Sands, Hellen Jo, Calivn Wong, Anthony Ha, Makkinoso, Gea, Sophia Foster-Dimino, Chris Kuzma, Johnny Ryan, Sophie Yanow, Chris “Elio” Eliopoulos, Michael Kupperman, Adam Bronson, An Nguyen, Mickey Zacchilli, Lisa Hanawalt, Anthony Wu, Evan Hadyen, Leslie Predy, Monika Uchiyama, y16o, Ryan Germick, Saicoink, Angie Wang, Tony Tulathimutte, Andre Syzmanowicz, Raymond Sohn, Michael DeForge, Mia Shwartz, Patrick Kyle, Derek Yu, Jordyn Bochon, Seibei, Ginette Lapalme, Nick Gazin, Harvey James, Zejian Shen, Robert Dayton, Aaron Mew, writers/artists

Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge, editors

self-published, 2010

64 pages

$12

Buy it and see an extensive preview at PrisonForBitches.com

The wonderful thing about recruiting a galaxy of underground comics and illustration stars to make a Lady Gaga fanzine is that no matter what kind of extravagant weirdness they concoct, there’s a better-than-even chance that at any moment the Lady herself could come along and comfortably out-weird them all. Nearly to a piece, the art, comics, photography, interviews, and essays assembled here by the Thickness team of Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge appear to have been created with a healthy appreciation for their own potential obsolescence in mind, and admiration and awe for the relentlessly and exuberantly creative young woman who’d make it happen. How else to explain the number of contributions that portray Gaga as godlike? In the hands of the Prison for Bitches team, Gaga is a queen seated on a giant telephone throwing trinkets to the huddled masses (Foster-Dimino); a vision appearing in dreams to espouse Anarcho-Gagaism to her supplicants (Yanow); a Big Brother-style disembodied head whose kohl-rimmed eyes stare at the viewer with a totalitarian sex-death gaze like something out of Metropolis (Kupperman); a She-Ra/ELA-esque figure riding through space atop a crystalline Battle-cat (Hayden); a Ray-Ban-wearing Baphomet (Predy); a giant sea goddess towering over the bodies of the drowned (Wang); an empress who lives to be 110 years old (DeForge); a severed head whose tongue, hair, and blood vessels are Cthulhoid tentacles (Aaron Mew). She is seen as supernatural, both a Delphic oracle of fabulousness and a Ring-claiming Galadriel proclaiming “All shall love me and despair.”

On the “love me” point, only a handful of the contributors work with the fact that she’s a very attractive person, but they’re among my favorites: André Syzmanowicz lovingly depicts the curves of her stomach, her breasts, her armpits, even as a werewolf creature gropes her from behind; a strip from Robert Dayton sees an ostensible fan complain about her mediocre music and ripped-off style, finally responding to the question “What do you like about her then?” with “Her navel—I want to lick her navel”; and right between the staples in the centerfold spread that anchors the book’s central full-color section, Mickey Zacchilli sticks the singer’s famously fit rear end.

Still other contributors take advantage of Gaga’s graphic potential for maximum maximalist imagemaking — artist after artist (Jo, Wang, Gazin, Yu, Bochon, Foster-Dimino) have a ton of fun with her hair, culminating in a spectacular caricature of her Coke-can curlers from the “Telephone” video by Harvey James. An Nguyen and the team of Hellen Jo & Calvin Wong provide concert reportage, the former with photos of her cosplaying fans, the latter with comics about the on- and off-stage spectacle of the concert experience.

A trio of prose pieces appear in what seems like ascending order of skepticism; in descending order, Adam Bronson has a funny piece that uses Deleuze and Hegel to analyze the relative potential of Gaga’s “Let’s Dance” and Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” to provoke violence in Filipino karaoke bars; Anthony Ha interviews Vanessa Grigoriadis, author of New York magazine’s seminal profile of Gaga’s origins and rise to fame, that’s best summed up by its title – “I’m a Total Fan of Hers, I Just Am Not a Huge Fan of Her Music”; editor Sands kicks the whole thing off with an utterly sincere and descriptively, persuasively argued “UNDISPUTED TOP 5 LADY GAGA SONGS,” featuring genuine gems like “[‘Alejandro’] sounds like ABBA’s ‘Fernando’ rubbing lotion all over Ace of Base’s ‘Don’t Turn Around’ while bathing nude on ‘La Isla Bonita'” and “[‘So Happy I Could Die’ is] really just a simple song about being convinced you are the hottest and most desirable person on the earth, and that this can be the best of all possible worlds if we allow ourselves the pleasure.” Taken in tandem, they’re like a debate between different modes of Gaga fandom, from arch irony to measured respect for a pop-culture needle-mover to downright love for someone who makes awesome songs to dance to.

The whole zine works like this, basically. Whatever it is you get out of Gaga — a pop-art deity, a gorgeous girl, an eye-inspiring spectacle, a thinkpiece generator, a hitmaker — by all means share that fun with a world that doesn’t have enough of it. This book is a snapshot of the Gaga conversation, post-“Telephone” video 2010; it’s a testament to the contributors and their subject alike that even now that the specifics of that conversation have now been rendered moot by an album full of pinball music and Clarence Clemons sax solos with a cover that reads “BORN THIS WAY” over a picture of the artist as a motorcycle with a human head, I’d love to hear them have it all over again. Prison for Bitches is a Little Monster must-have for any Gaga fan.