Posts Tagged ‘Jaime Hernandez’

Friday night with Vorpalizer

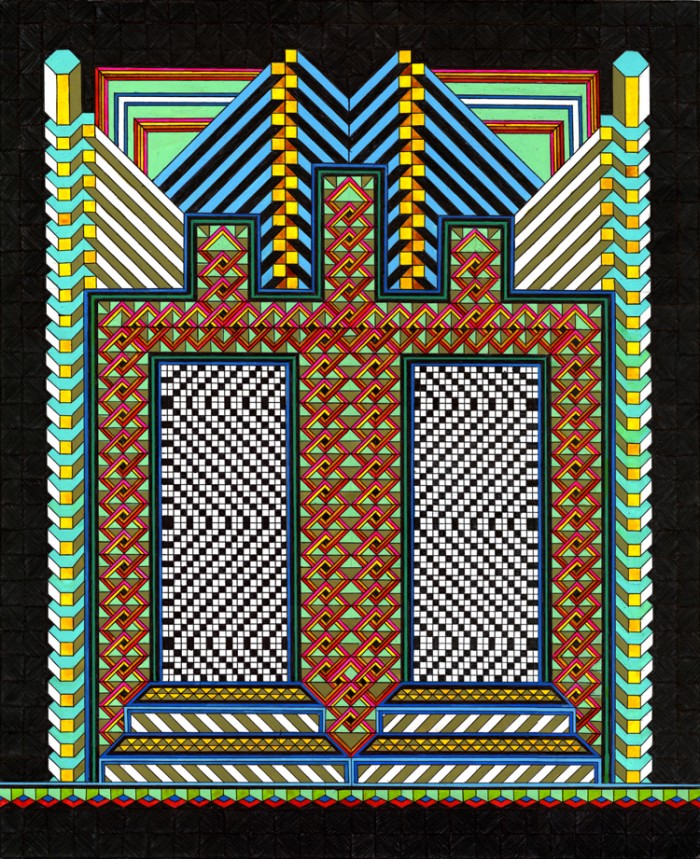

June 7, 2013Over the past couple of weeks I’ve written about Memory Palaces by Edie Fake, “The Sea-Bell, or Frodo’s Dreme” by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Ghoul Man” by Jaime Hernandez, and “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe for Vorpalizer. Check them out.

The Four Horsemen

September 26, 2012I interviewed Jaime Hernandez, Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, and Gilbert Hernandez for Rolling Stone. Comics game Mount Rushmore.

(photo by Meredith Rizzo)

How I spent my Saturday morning

September 18, 2012Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

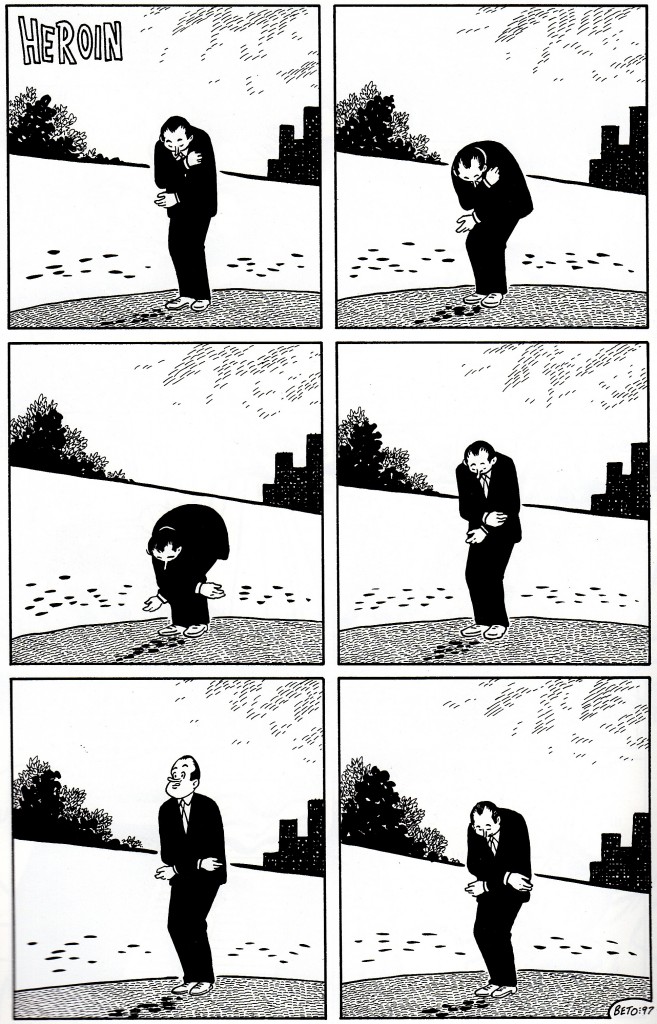

July 15, 2012Gilbert and Jaime are both masters of the form of comics. That’s in addition to their character work, their sheer illustrative chops, and so on; indeed it may be the most exciting thing about them. In the case of both brothers I’ve spent a long time chewing over just a few handfuls of panels, unpacking what went into them. Here’s Gilbert’s silent, six-panel comic “Heroin,” one of three one-page shorts he made with that title. It’s just a man against one of Beto’s soon-to-be-trademark dismal nowherescapes, clutching his arm, doubling over, standing back up, hunching over again. We don’t know who he is or where he is or what he’s doing or what its connection is, specifically, to the titular substance — he could be a junkie on the nod, sure, but then why is he also Richard Nixon (or maybe it’s Bob Hope)? Whether it’s about the drug specifically or addictive, destructive influences generally (as are the other two “Heroin” strips) doesn’t really matter, since the effect stems almost entirely from the building blocks of the comic itself: the man, the background, the grid layout, the lack of any text save the title, the rhythm that builds up as we watch his body contort, the three big blocks of black in each panel (trees, man, buildings), the hands pointing in opposite directions, the diagonal hill line bisecting each panel. Every element combines to convey discomfort and unease, the sense of being at the mercy of something that lets you straighten out just long enough for it to be crushing when it knocks you back down. Long before I’d actually read any comics by Los Bros I saw this page reproduced in an issue of The Comics Journal and it has worked its way into the fabric of my comics brain ever since. It occurred to me just the other day that I’ve even done a homage to it without realizing it. I think it’s a perfect comic.

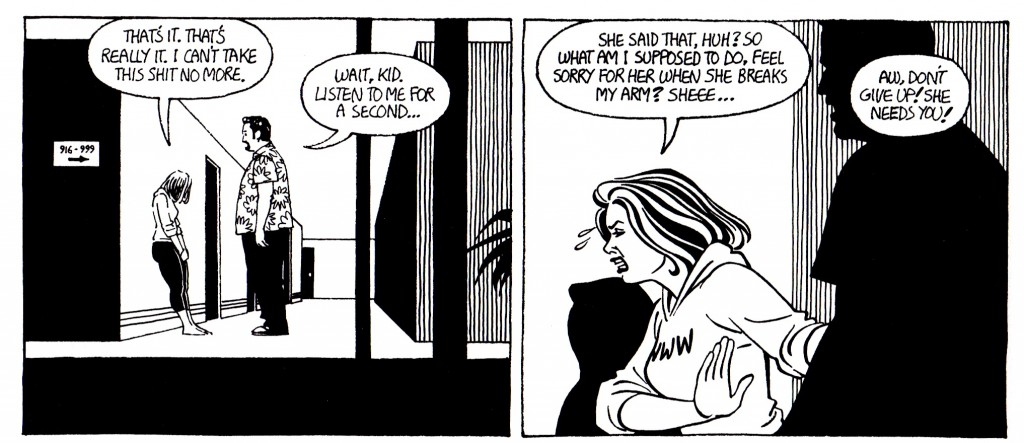

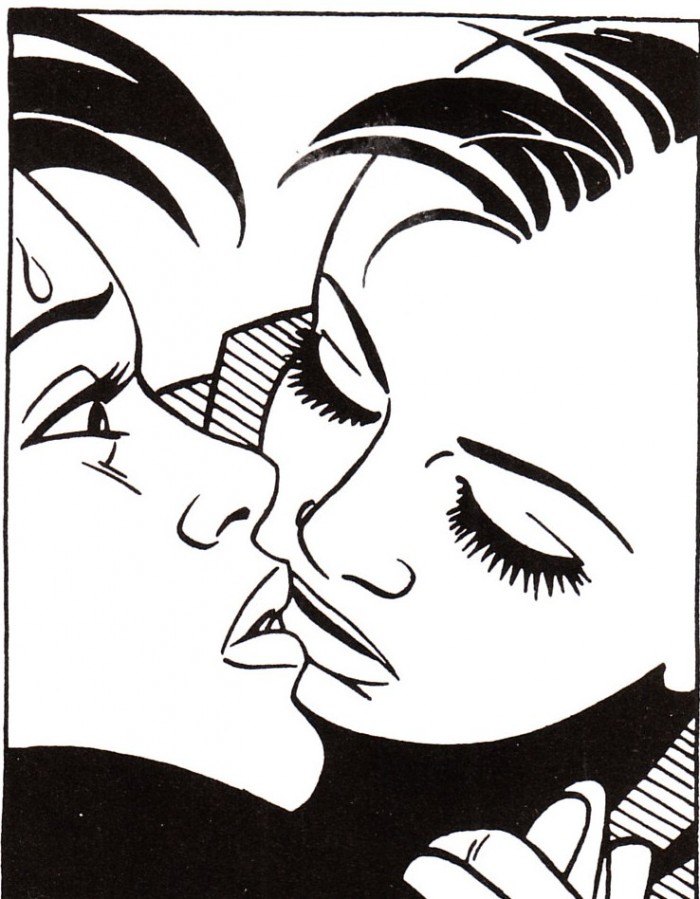

And here’s two panels from “In the Valley of the Polar Bears” by Jaime. Maggie’s been working as the kayfabe “accountant” for her wrestling-champ aunt Vicki, something of a terror in and out of the ring, but the two are barely speaking. Vicki has just confided in her wrestler boyfriend Cash that the reason she’s been treating Maggie so badly is because she cares about her a lot and is hurt by Maggie’s seeming indifference in return. So here, Cash approaches Maggie to tell her about her aunt’s secret soft spot — and then blam, next panel, it’s already been told. Jaime doesn’t show us the conversation. He doesn’t slap a big “Five minutes later…” caption up there. He doesn’t alter the size of the panels or the gutters to imply the passage of time. He doesn’t cut to another scene in between. He doesn’t show Maggie and Cash in another location so that we’d know time must have passed for them to get from place to place. He zooms in a bit but other than that they’re even in the same basic spatial configuration. He pretty much breaks every rule of how jumps in time are conveyed in comics, and yet it’s still crystal clear what happened. Talk about no-fat storytelling. Why belabor the re-presentation of information we readers already have? And why monkey with shit to explain what you’re not showing us when you can simply not show it to us and assume we’re smart enough to follow? These two panels are so bold, so full of lessons in how to tell a story with comics. I think about them all the time.

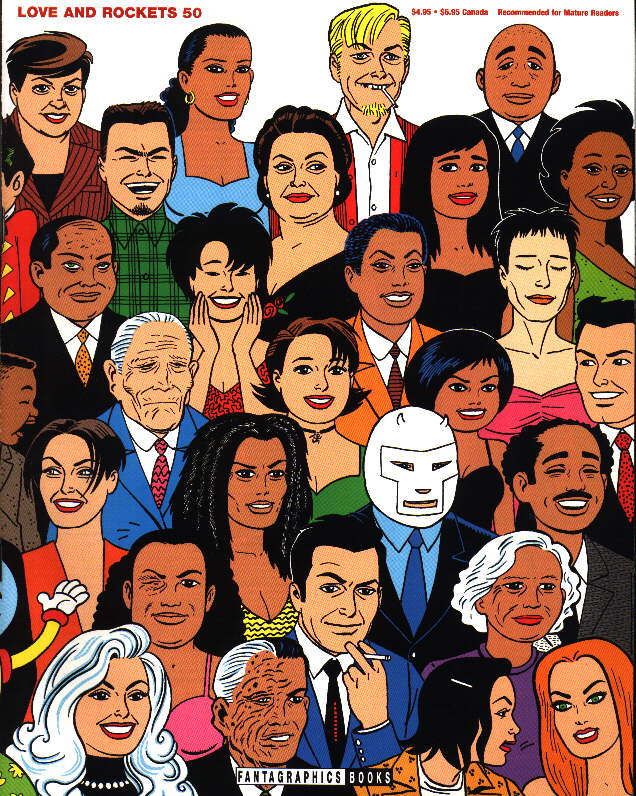

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

July 14, 2012Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez have each been telling the stories of the same group of characters, continuously, for three decades. They’ve done lots of other stuff, Gilbert especially, but that’s the bulk of what they’ve done. No one else in comics has done it. No one’s even come close. Could someone else do it? Could someone else tell the life story of their characters, over an actual life span, and have a lot of people care passionately about where those lives end up? I won’t say it’s unimaginable, the idea of someone else doing it, because there are enough similar cases out there for you to imagine those other people doing it, and it’s only then that the gulf between Los Bros and everyone else becomes so clear. What if Bryan Lee O’Malley just kept going with Scott Pilgrim until he hit Vol. 30? What if Dave Sim had never lost his mind? What if all the B.P.R.D. spinoffs were written and drawn by Mike Mignola? What if Achewood were a comic book and Chris Onstad never burned out on it? What if Erik Larsen’s main touchstone for Savage Dragon were Márquez rather than Kirby? What if The Walking Dead were filled with Rick-level characters, instead of Rick and a bunch of other people for Rick to react to? What if Alison Bechdel made a series of Dykes to Watch Out For graphic novels instead of memoirs? What if Harvey Pekar had made stories up instead of writing them down? What if all of these things lasted for thirty years? And oh yeah, what if all of these people had siblings doing the exact same thing at the same time under the same title? It’s only when you see all the hoops one would have to jump through even to come close to what Beto and Xaime have accomplished that you really appreciate that hey, they’re the ones who built the hoops.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

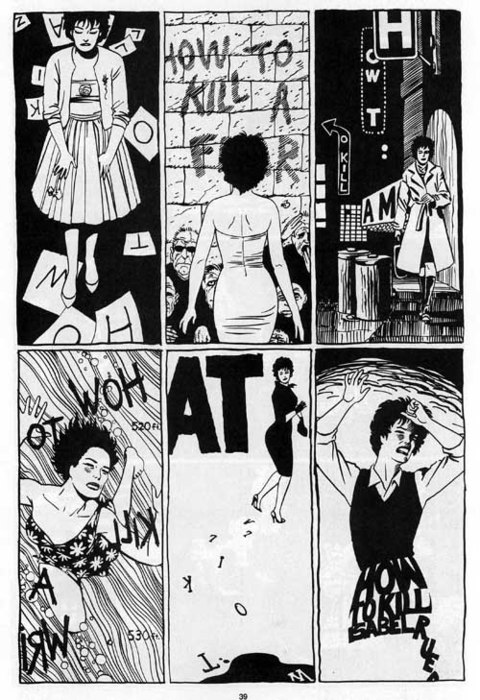

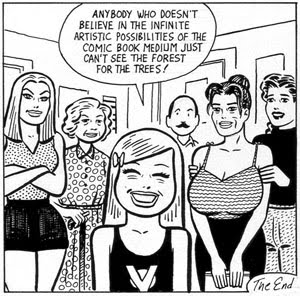

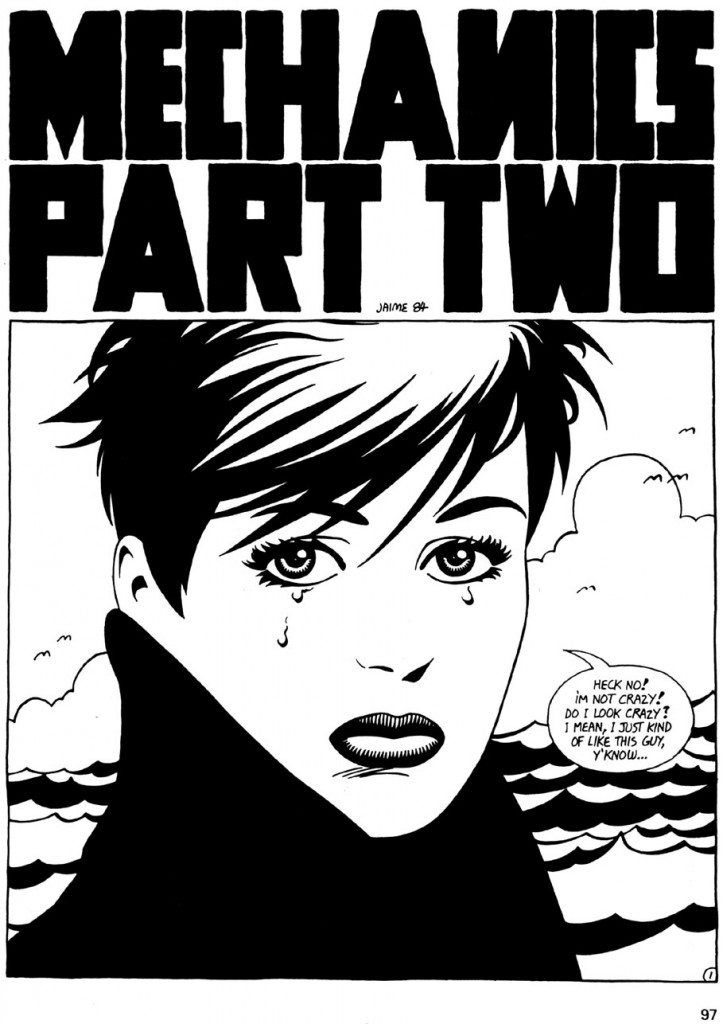

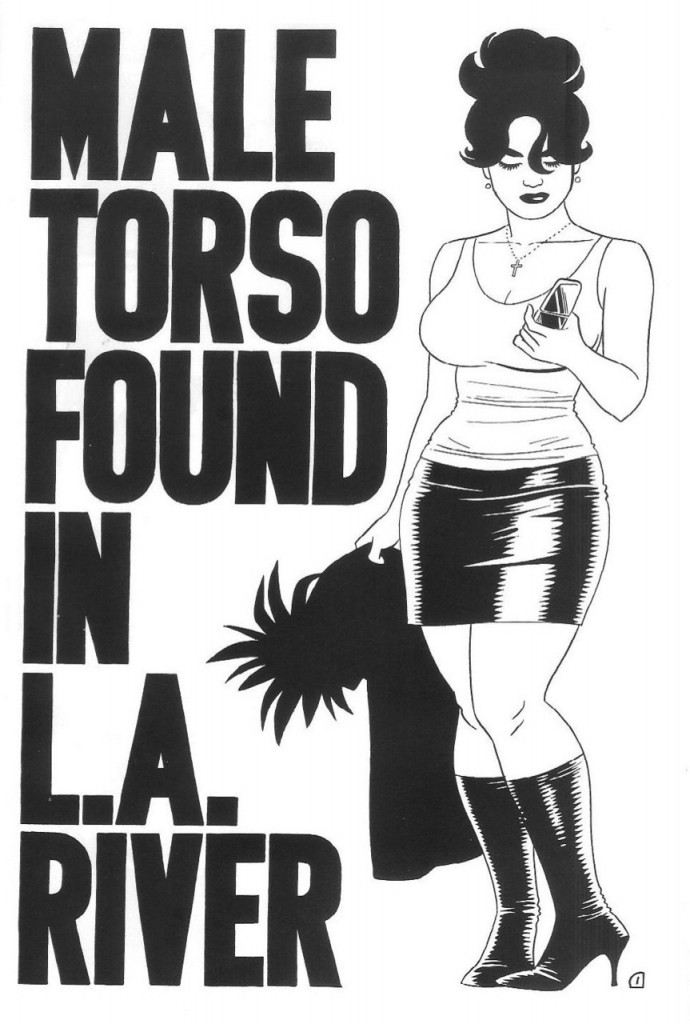

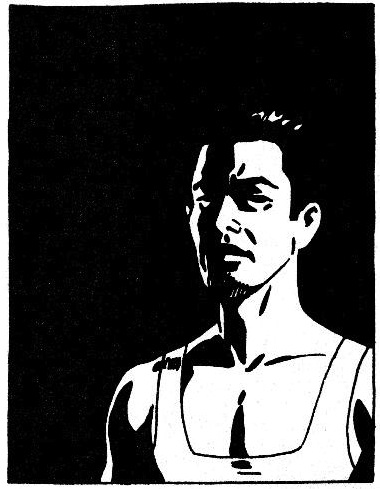

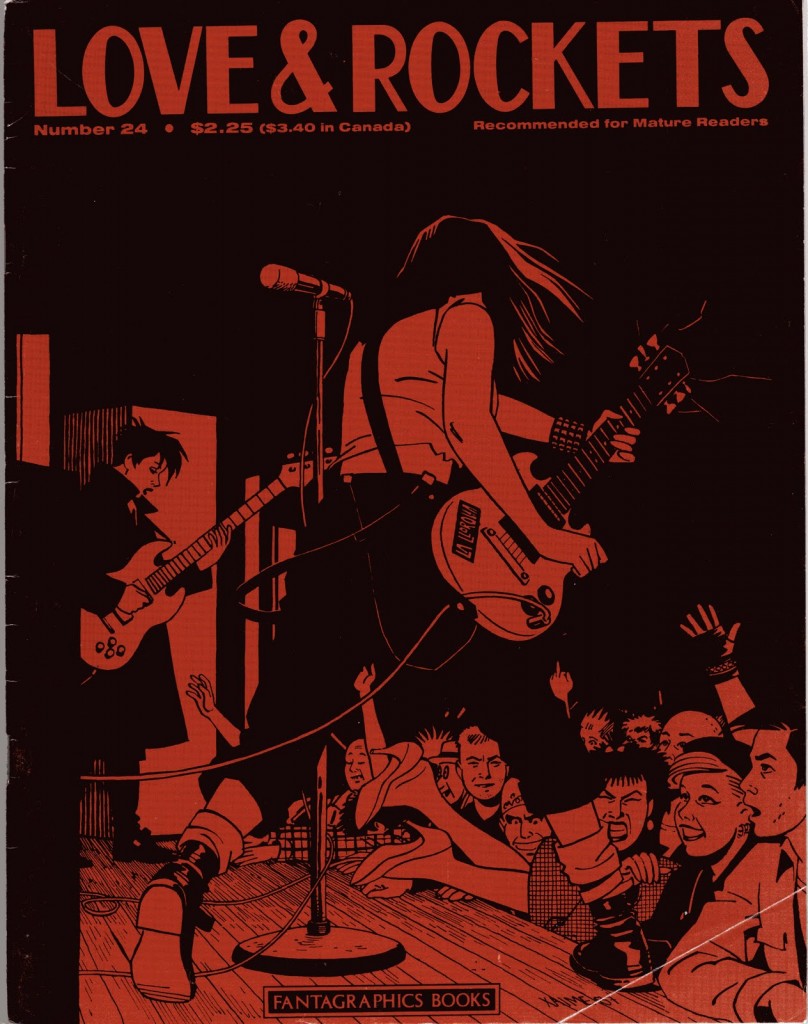

July 11, 2012Jaime Hernandez is comics’ greatest maker of standalone images. His blacks, his typography, his sense of style, the drama of his line, the sense of balance and momentum even within a single image, his use of powerful moments to convey character, the whole nine. Out of all his peers in the ’80s and ’90s alternative comics movement — the stuff I think of as High Alt, the solo anthology series cartoonists who eventually coalesced around Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly, Xaime and Beto and Ware and Burns and Clowes and Brown and Doucet and Bagge and Tomine and Sacco and Woodring and French — his makes him uniquely suited for the Tumblr era, when the rebloggable, context-free image is king. As such he stands the best chance of elbowing his way into the new canon currently being established as a reaction against High Alt and its forebears, consisting mainly of high-impact, visually dazzling genre comics whose work thrives in a one-at-a-time context — Kirby and Moebius and Otomo and Miller and Chaykin and Manara and pre-alt Mazzucchelli and McCarthy and Graham. But his best images often come within the flow of a story in addition to pin-ups, posters, covers, and title pages, and his interests broaden the canon-of-spectacle beyond solving problems through violence and/or sexy stylishness. They work equally well as vehicles for devastating emotional reveals, or as t-shirts.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

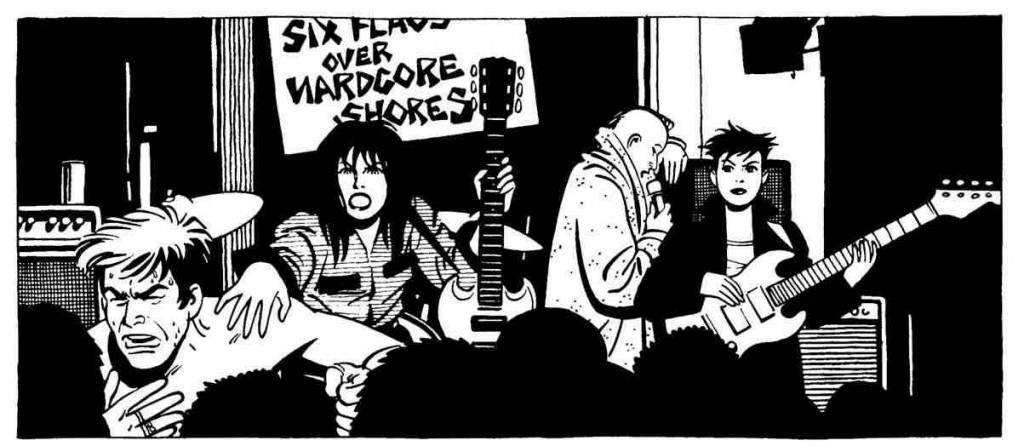

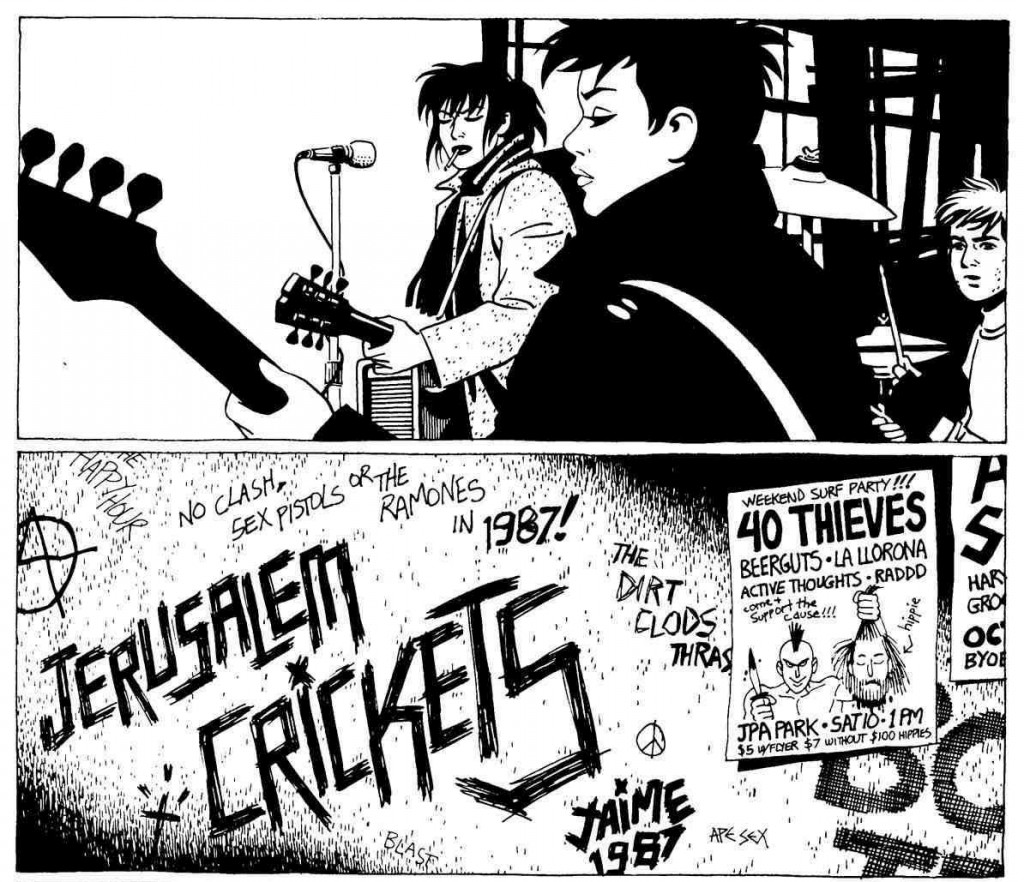

July 9, 2012No cartoonist has ever captured the spirit of rock and roll — listening to it, watching it, performing it, defining your life with it — like Jaime Hernandez. Vanishingly few have even come close; most attempts are cringeworthy. Jaime not only nailed the style, and the intensity, and the specific idiom of his punk milieu (the graffito “NO CLASH, SEX PISTOLS OR THE RAMONES IN 1987!” in the panels below is worth more than entire critics’ bodies of work), and the nuts-and-bolts stuff like the body language of people playing music on stage, he also chronicled the lives of the characters involved long enough to be basically the only cartoonist ever to explicitly examine what it’s like when you grow up and grow older and discover that you no longer look and act and think like someone in the pit at your favorite band’s show.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

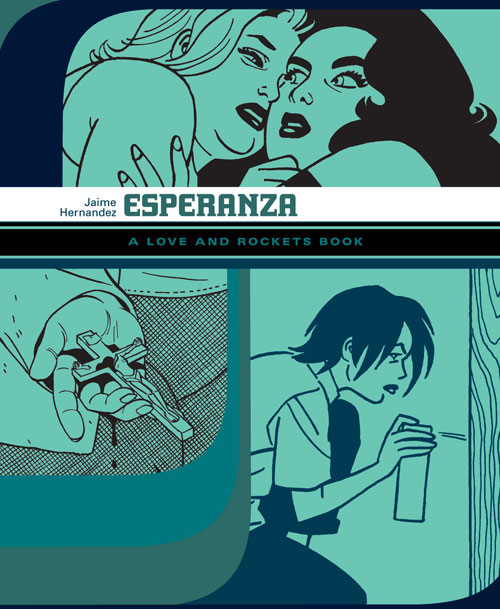

Comics Time: Esperanza

April 4, 2012Esperanza

Love and Rockets Library: Locas, Book Five

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

248 pages

$18.99

Fantagraphics, 2011

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

The 20 Best Comics of 2011

January 1, 201220. Uncanny X-Force (Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña, Marvel): In a year when the ugliness of the superhero comics business became harder than ever to ignore, it’s fitting that the best superhero comic is about the ugliness of being a superhero. Remender uses the inherent excess of the X-men’s most extreme team to tell a tale of how solving problems through violence in fact solves nothing at all. (It has this in common with most of the best superhero comics of the past decade: Morrison/Quitely/etc. New X-Men, Bendis/Maleev Daredevil, Brubaker/Epting/etc. Captain America, Mignola/Arcudi/Fegredo/Davis Hellboy/BPRD, Kirkman/Walker/Ottley Invincible, Lewis/Leon The Winter Men…) Opeña’s Euro-cosmic art and Dean White’s twilit color palette (the great unifier for fill-in artists on the title) could handle Remender’s apocalyptic continuity mining easily, but it was in silent reflection on the weight of all this death that they were truly uncanny.

19. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969 (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, Top Shelf/Knockabout): I’ll admit I’m somewhat surprised to be listing this here; I’ve always enjoyed this last surviving outpost of Moore’s comics career but never thought I loved it. But in this installment, Moore and O’Neill’s intrepid heroes — who’ve previously overcome Professor Moriarty, Fu Manchu, and the Martian war machine — finally succumb to their own excesses and jealousies in Swinging London, allowing a sneering occult villain to tear them apart with almost casual ease. It’s nasty, ugly, and sad, and it’s sticking with me like Moore’s best work.

18. The comics of Lisa Hanawalt (various publishers): As I put it when I saw her drawing of some kind of tree-dwelling primate wearing a multicolored hat made of three human skulls stacked on top of one another, Lisa Hanawalt has a strange imagination. And it’s a totally unpredictable one, which is what makes her comics – whether they’re reasonably straightforward movie lampoons or the extravagantly bizarre sex comic she contributed to Michael DeForge and Ryan Sands’s Thickness anthology, as dark and damp as the soil in which its earthworm ingénue must live – a highlight of any given day a new one pops up.

17. Daybreak (Brian Ralph, Drawn and Quarterly): Fort Thunder’s single most accessible offspring also proves to be its bleakest, thanks to an extended collected edition that converts a rollicking first-person zombie/post-apocalypse thriller into a troubling meditation on the power of the gaze. Future artcomics takes on this subgenre have a high bar to clear.

16. Habibi (Craig Thompson, Pantheon): It’s undermined by its central characters, who exist mainly as a hanger on which this violent, erotic, conflicted, curious, complex, endlessly inventive coat of many colors is hung. But as a pure riot of creative energy from an artist unafraid to wrestle with his demons even if the demons end up winning in the end, Habibi lives up to its ambitions as a personal epic. You could dive into its shifting sands and come up with something different every time.

15. Ganges #4 (Kevin Huizenga, Coconino/Fantagraphics): Huizenga wrings a second great book out of his everyman character’s insomnia. It’s quite simple how, really: He makes comics about things you’d never thought comics could be about, by doing things you never thought comics could do to show you them. Best of all, there’s still the sense that his best work is ahead of him, waiting like dawn in the distance.

14. The Congress of the Animals (Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics): The potential for change explored by the hapless Manhog in last year’s Weathercraft is actualized by the meandering mischief-maker Frank this time around. While I didn’t quite connect with Frank’s travails as deeply as I did with Manhog’s, the payoff still feels like a weight has been lifted from Woodring’s strange world, while the route he takes to get there is illustrated so beautifully it’s almost superhuman. It’s the happy ending he’s spent most of his career earning.

13. Mister Wonderful (Daniel Clowes, Pantheon): Speaking of happy endings an altcomix luminary has spent most of his career earning! Clowes’s contribution to the late, largely unlamented Funny Pages section of The New York Times Magazine is briefly expanded and thoroughly improved in this collected edition. Clowes reformats the broadsheet pages into landscape strips, eases off the punchlines and cliffhangers, blows individual images up to heretofore unseen scales, and walks us through a self-sabotaging doofus’s shitty night into a brighter tomorrow.

12. The comics of Gabrielle Bell (various publishers): Bell is mastering the autobiography genre; her deadpan character designs and body language make everything she says so easy to buy – not that that would be a challenge with comics as insightful as her journey into nerd culture’s beating heart, San Diego Diary, just by way of a for instance. But she’s also reinventing the autobiography genre, by sliding seamlessly into fictionalized distortions of it; her black-strewn images give a somber, thoughtful weight to any flight of fancy she throws at us. What a performance, all year long.

11. The Armed Garden and Other Stories (David B., Fantagraphics): Religious fundamentalism is a dreary, oppressive constant in its ability to bend sexuality to mania and hammer lives into weapons devoted to killing. But it has worn a thousand faces in a millennia-long carnevale procession of war and weirdness, and David B. paints portraits of three of its masks with bloody brilliance. Focusing on long-forgotten heresies and treating the most outlandish legends about them as fact, B.’s high-contrast linework sets them all alight with their own incandescent madness.

10. Too Dark to See (Julia Gfrörer, Thuban Press): It was a dark year for comics, at least for the comics that moved me the most. And no one harnessed that darkness to relatable, emotional effect better than Julia Gfrörer. Her very contemporary take on the legend of the succubus was frank and explicit in its treatment of sexuality, rigorously well-observed in its cataloguing of the spirit-sapping modern-day indignities that can feed depression and destroy relationships, and delicately, almost tenderly drawn. It’s like she held her finger to the air, sensed all the things that can make life rotten, and cast them onto the pages. She made something quite beautiful out of all that ugly.

9. The comics and pixel art of Uno Moralez (self-published on the web at unomoralez.com): What if an 8-bit NES cut-scene could kill? The digital artwork of Uno Moralez — some of it standard illustrations, some of it animated gifs, some of it full-fledged comics — shares its aesthetic with The Ring‘s videotape or Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie: a horror so cosmically black, images so unbearably wrong, that they appear to have leaked into and corrupted their very medium of transmission. Moralez fuses crosses the streams of supernatural trash from a variety of cultures — the legends and Soviet art of his native Russia, the horror and porn manga of Japan, the B-movies and horror stories of the States, the formless sensation aesthetic of the Internet itself — into a series of images that is impossible to predict in its weirdness but totally unflagging in its sense that you’d be better off if you’d never laid eyes on it. I can’t wait to see more.

8. The comics of Michael DeForge (various publishers): The last time you saw a cartoonist this good and this unique this young, you were probably reading the UT Austin student newspaper comics section and stumbling across a guy named Chris Ware. All four of DeForge’s best-ever comics — his divorced dad story in Lose #3, his shape-shifting/gender-bending erotica in Thickness #2, his self-published art-world fantasia Open Country, and his gorgeously colored body-horror webcomic Ant Comic — came out this year, none of them looking anything at all like anything you could picture before seeing your first Michael DeForge comic. It’s almost frightening to think where he’ll be five years from now, ten years from now…or even just this time next year.

7. The comics and art of Jonny Negron (various publishers): What if someone took Christina Hendricks’s walk across the parking lot and trip to the bathroom in Drive and made an entire comics career out of them? That is an enormously facile and reductive way to describe the disturbing, stylish, sexy, singular work of Jonny Negron, the breakout cartoonist of the year, but it at least points you in the right direction. No one’s ever thought to combine his muscular yet curiously dispassionate bullet-time approach to action and violence, his Yokoyama-esque spatial geometry, his attention to retrofuturistic fashion and style, his obvious love of the female body in all its shapes and sizes, and his ambient Lynchian terror; even if they had, it’d be tough to conceive of anyone building up his remarkable body of work in such a short period of time. Open up your Tumblr dashboard or crack an anthology (Thickness, Mould Map, Study Group, Smoke Signal, Negron and Jesse Balmer’s own Chameleon), and chances are good that Negron was the weirdest, best, most coldly beautiful thing in it. It’s like a raw, pure transmission from a fascinating brain.

6. The Wolf (Tom Neely, I Will Destroy You): Neely’s wordless, painted, at-times pornographic graphic novel feels like the successful final draft to various other prestigious projects’ false starts. It’s a far less didactic, more genuinely erotic attempt at high-art smut than Dave McKean’s Celluloid; a less self-conscious, more direct attempt at frankly depicting both the destructive and creative effects of sex on a relationship via symbolism than Craig Thompson’s Habibi; a blend of sex and horror and narrative and visual poetry and ugly shit and a happy ending that succeeds in each of these things where many comics choose to focus on only one or two.

5. The Cardboard Valise (Ben Katchor, Pantheon): Prep your time capsules, folks: You’d be hard pressed to find an artifact that better conveys our national predicament than Ben Katchor’s latest comic-strip collection, a series of intertwined vignettes created largely before the Great Recession and our political class’s utter failure to adequately address it, but which nonetheless appears to anticipate it. Its message — that blind nationalism is the prestige of the magic trick used by hucksters to financially and culturally ruin societies for their own profit — is delightfully easy to miss amid Katchor’s remarkable depictions of lost fads, trends, jobs, tourist attractions, and other detritus of the dying American Century. He’s the very most funnest Cassandra around.

4. Love from the Shadows (Gilbert Hernandez, Fantagraphics): I picture Gilbert Hernandez approaching his drawing board these days like Lawrence of Arabia approaching a Turkish convoy: “NO PRISONERS! NO PRISONERS!” In a year suffused with comics funneling pitch-black darkness through a combination of sex and horror, none were blacker, sexier, or more horrific than this gender-bending exploitation flick from Beto’s “Fritz-verse.” None also functioned as a rejection of the work that made its creator famous like this one did, either. Not a crowd-pleaser like his brother, but every bit as brilliant, every bit as fearless.

3. Garden (Yuichi Yokoyama, PictureBox): Like a theme park ride in comics form — with the strange events it chronicles themselves resembling a theme park ride — Yokoyama’s book is a breathtaking, breathless experience. Alongside his anonymous but extravagantly costumed non-characters, we simply go along for the ride, exploring Yokoyama’s prodigious, mysterious imagination as he concocts a seemingly endless stream of increasingly strange interfaces between man and machine, nature and artifice. As a metaphor for our increasingly out-of-control modern life it’s tough to top. As pure thrilling kinetic cartooning it’s equally tough to top.

2. Big Questions (Anders Nilsen, Drawn & Quarterly): Last year, I wrote that if the collected edition of Nilsen’s long-running parable of philosophically minded birds and the plane crash that turns their lives upside-down didn’t top my list whenever it came out, it must have been some kind of miracle year. Turns out that it was. But you’d pretty much have to create a flawless capstone to a thirty-year storyline of neer-peerless intelligence and artistry to top this colossal achievement. Nilsen’s painstaking, pointillist cartooning and ruthless examination of just how little regard the workings of the world have for any given life, human or otherwise, marks him as the best comics artist of his generation, and solidifies Big Questions‘ claim as the finest “funny animal” comic since Maus.

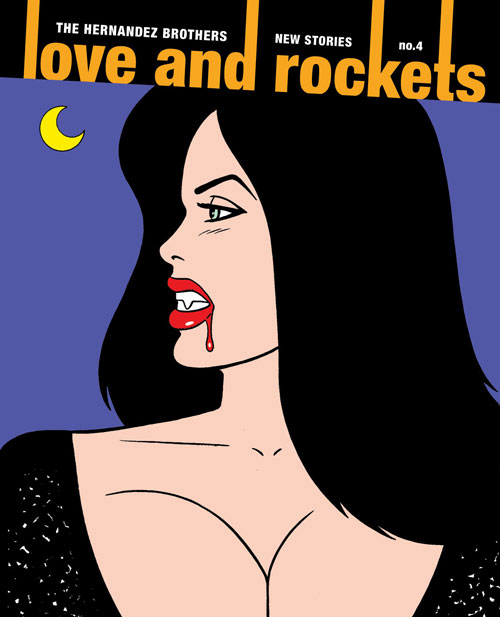

1. Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 (Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Fantagraphics): Gilbert got his due elsewhere on my list, so let’s ignore his contribution to this issue, which advance the saga of his bosomy, frequently abused protagonist Fritz Martinez both on and off the sleazy silver screen. Instead, let’s add to the chorus praising Jaime’s “The Love Bunglers” as one of the greatest comics of all time, the point toward which one of the greatest comics series of all time has been hurtling for thirty years. In a single two-page spread Jaime nearly crushes both his lovable, walking-disaster main characters Maggie and Ray with the accumulated weight of all their decades of life, before emerging from beneath it like Spider-Man pushing up from out of that Ditko machinery. You can count the number of cartoonists able to wed style to substance, form to function, this seamlessly on one hand with fingers to spare. A masterpiece.

You’ve come a long way, Jaime: or how I learned to stop worrying and love Love and Rockets

October 21, 2011I wrote about “getting into” Love and Rockets for Robot 6. It’s the culmination of a week’s worth of posts on the subject. Take a look.

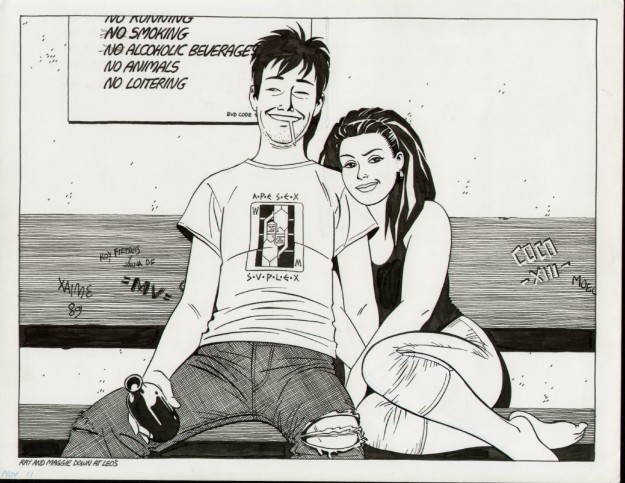

He’s your worst nightmare

October 20, 2011Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 is a great comic

October 17, 2011Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

August 1, 2011Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, August 2011

104 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 will turn any fan of Los Bros Hernandez into the host of The Chris Farley Show. “Remember? That time? When you drew Calvin’s plaid shirt? So that the plaid was always facing in the same direction? No matter how much Calvin moved?…That was awesome.” I am seriously finding it difficult, if not impossible, to review this comic without simply hitting the bullets-and-numbering button and whipping up a list of everything in it that amazed me. It would be a long list, too. But I’m abstaining as much as I can — to challenge myself for starters, and to avoid spoiling the comic for those of you who haven’t yet read it (which is probably most of you since it’s not out yet) for the most part. But I’m also holding off on that listicle because I think it’s a cheat. The fact of the matter is that while reading this book I discovered that I’m at least as attached to Ray Dominguez and Fritz Martinez, the protagonists of Jaime and Gilbert’s contributions respectively, as I am to a decent number of real people in my life. So sure, I could rattle off the ways in which Xaime and Beto continually prove themselves to be among the most graphically inventive and entertaining cartoonists alive some three decades into their careers — the crosshatching on Ray’s shirt and Maggie’s sofa; Gilbert’s use of wavy, puddle-shaped, impenetrable fields of black in his vampire story; the impact of the just-this-side-of-parallel lines of Angel’s body as she bends her leg to put on a high heel; the upside-down lava-lamp shape of Fritz’s legs in a skirt, used as an anchor for panel after panel of her simply walking around town with her agent ex; dredging up a long-ago, possibly long-forgotten character, drawing him as a late-middle-aged man in a way that makes him unrecognizable until you realize just how recognizable he is; the smashed-skull-as-cubist-masterpiece in Gilbert’s customary burst of horrifying ultraviolence; the holy shit moment when you realize the visual structure to that montage spread from Jaime’s story; Gilbert storming the ramparts of the vampire story and launching sex and violence back into it like payloads from a trebuchet; Jaime serving up a story whose snapshot style echoes comparable material from “Wigwam Bam” in significant and story-relevant ways; tracing the similarities and differences between Killer and Fritz via the characters they play, the use of their amazing bodies fraught with story information. And hey, look at that, I did rattle them off! But in the end, how it looks pales in insignificance next to what happens, because making it look that good is a means to the end of imparting just how much what happens matters. Ray’s shirt and Fritz’s legs, the shadow of the vampire and the structure of the montage — they’re just landmarks to remind you where you were when you found out if Ray and Fritz and Maggie were going to get happy endings, or not. It’s the easiest thing in the world to understand, and it’s the hardest thing in the world to do, and it’s magic, pure magic, to do it this well.

Comic of the Year of the Day: Love and Rockets: New Stories #3

December 19, 2010Every day throughout the month of December, Attentiondeficitdisorderly will spotlight one of the best comics of 2010. Today’s comic is Love and Rockets: New Stories #3 by Gilbert Hernandez and Jaime Hernandez, published by Fantagraphics — career-best work from cartoonists with two of the best careers in the medium.

On Jaime’s “Browntown”/”The Love Bunglers”:

…ever since I read it, when I think of it, I just keep thinking to myself, “Poor [name]. Poor, poor [name].” It makes me want to cry! Cry for an imaginary person I’d never read about until a few pages earlier. (It’s the flipside of feeling proud of the entirely imaginary Hopey Glass for becoming a teacher’s assistant, I guess.) Such power!…I will never forget reading this book.

On Gilbert’s “Scarlet by Starlight”/”Killer * Sad Girl * Star”:

the brutal exploitation of children at the center of “Scarlet by Starlight” — delivered in a grotesquely matter-of-fact panel, savagely angry and awful — is echoed by the far milder but still insidious sexualization of “Killer * Sad Girl * Star” later on in issue #3…and, of course, it compliments and reinforces Jaime’s “Browntown”/”The Love Bunglers” suite in that same volume.

Click here for a full review of Jaime’s contributions to the issue and click here for a full review of Gilbert’s contributions to the issue; click either one for purchasing information.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Amor y Cohetes

November 10, 2010Amor y Cohetes

(Love and Rockets Library: Short Stories)

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Mario Hernandez, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, 2008

280 pages

$16.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

One of the things I’ve missed out on in reading through Love and Rockets one Bro at a time is seeing where they stood in relation to each other. I’m told by at least one trusted reader who was there at the time that “it’s the way they played off each other!” is an overrated element to the original serial-anthology format, but that’s fine, because my interest in this topic was more historical than critical. Isn’t it fascinating to know, for example, that “The Death of Speedy Ortiz” was in the same issues as “Poison River”? And I’ve heard straight from the Bros’ mouths that seeing what the other one was doing in the early issues helped shape the storylines that would define each of them: Gilbert was so impressed by Jaime’s obvious mastery of the “cute girls hanging out in a science-fiction setting” set-up in his Locas strips that he abandoned his similar material to create Palomar; then Jaime was so impressed with the extensive, realistic character work Gilbert was doing in Palomar that he beefed up that aspect of the Locas stories. It wasn’t so much “I’ll see you and raise” (although surely that’s a part of it, as it is whenever any talented people work in proximity) as it was each brother seeing what areas in their shared ideaspace gave them the room to bust loose.

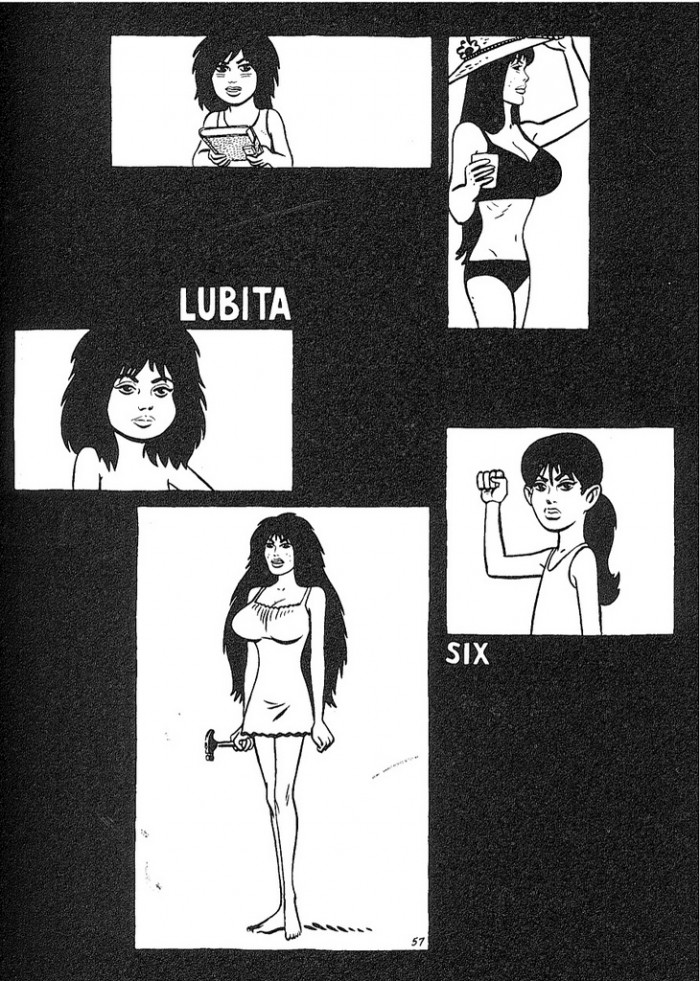

In collecting all the (mostly) non-Locas, non-Palomar odds’n’ends from the initial run of Love and Rockets from both Gilbert and Jaime–and Mario too, the “sometimes Y” to Beto and Xaime’s AEIOU–Amor y Cohetes reinforces that conception of the brothers’ working relationship. It’s not one-upsmanship, it’s not trading eights, it’s more a matter of pulling from a collective pool of ideas about comics. For example, it’s striking how similar the two brothers’ science-fiction work looks. In “BEM,” the SF adventure that I believe was Beto’s very first L&R material, he hatches and spots blacks and draws romance-comic female faces in the way you expect from Jaime’s genre work. I mean, it’s still recognizably Gilbert, but it’s quite clear that both brothers conceived of these kinds of stories as ones that are by default painted with the same visual palette. As time passes, Gilbert’s sci-fi stuff dwindles down to the single storyline of Errata Stigmata, the asymmetrically coiffed character whose omnipresence in L&R promo material over the years always left me wondering who the hell she was since I’d seen neither hide nor hair of her in Palomar or Locas; even then, his layouts are wide open, using far fewer panels per page, and are driven by vast fields of stylishly designed black–Jaime-esque, in other words. Meanwhile, a pair of punk-based Beto stories–one the fictional history of a shoulda-woulda-coulda been the next big thing bad as told by one of their fans, the other an autobio vignette about the night his 17-year-old future wife puked her way through his would-be panty-dropping tour of punk hotspots–show the same easy familiarity and casual mastery of that milieu that Jaime’s does. How’d he do it without all the practice Jaime had? My conclusion is that, like how sci-fi should look a certain way, knowing how to write punk comics is just part of their shared gestalt. Hell, Beto even contributes an awesome little wrestling story, about the real-life night he saw (pre-Adorable) Adrian Adonis basically go nuts, that further proves the point.

The road goes both ways, of course. Jaime’s light-hearted sci-fi-comedy romps with pretty teenager Rocky Rhodes and her absolutely adorable robot sidekick Fumble eventually veer off into the sort of sad, you-can-never-go-back cul de sac of regret that’s normally Beto’s territory. There’s also a barely-veiled autobio story about the day a KKK event in his neighborhood provoked a riot that feels more Love and Rockets X than Locas. When the Bros swap characters for a special issue, Jaime hews much closer to the spirit of Palomar in his Luba/Maricela/Riri story than Beto does in his proto-Birdland gender-bending sci-fi sex romp with the Locas (whom he eventually transmogrifies into Locos!). To put even more of a point on it, Jaime takes a zany old Looney Tunes-style comic Beto did as a kid and redraws it with Maggie and Hopey in the lead roles, and damn if it doesn’t feel like the kind of kinetic, wordless romps Beto throws in as short stories from time to time as an adult.

Thrown into this mix for the first time in the L&R books I’ve read is Mario. Dude’s an accomplished cartoonist too, and in a style that I think anticipated a lot more comics I’ve seen than Jaime’s or Gilbert’s, believe it or not–his blobby, dynamically dashed-down inks feel alt-Euro to me, poised halfway between expressionism and naturalism. His main storyline, about the fallout from a coup d’état in a slightly sci-fi-tinged Latin American country, unfolded over the course of short stories spaced out over years, and offers more proof that the Bros were all building off the same foundation–it’s quite easy to place his “Somewhere in California”/”Somewhere in the Tropics” political thriller somewhere between Maggie and Rena’s Mechanix-era revolutionary misadventures and Gilbert’s serious-as-a-heart-attack Cold War/Drug War shocker Poison River. Which makes sense, I suppose, given that he and Beto collaborated on several of the strips.

Ultimately it’s Gilbert who emerges as the star of Amor y Cohetes. While Mario’s stuff feels like a cameo and Jaime’s like a detour, Gilbert’s non-Palomar work comes across like a second main throughline for his career. Whether incorporating Frida Kahlo’s style and a dizzying array of cultural and political eyeball kicks into his biographical strip about her, placing autobiographical stories and dialogue in the caption boxes and word balloons of totally incongruous superhero and sci-fi artwork, crafting harsh and mostly wordless short stories about violence, or developing Errata Stigmata into a damage case every bit the equal of a Palomar resident, he comes across as restless and relentless in his desire to do whatever he can think of doing with comics. All three Bros shine on this shared stage, but Beto’s the one pushing through the audience and taking it out to the street. It’s exciting to watch that shared ideaspace expand.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #3

October 25, 2010Love and Rockets: New Stories #3

featuring “The Love Bunglers Part One,” “Browntown,” and “The Love Bunglers Part Two”

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

104 pages

$14.99

If I had to sum up all of the post “Wigwam Bam/Chester Square/Bob Richardson” Locas stories in a phrase, it would be “coming to terms.” With adulthood, with the death of punk, with a career, with the past, with reaching middle age, with falling in and out of love, with family and friends and heroes, with your limitations, even with really good things like your talents. (Heck, even this story reveals that Maggie’s planning to open up her own garage, finally utilizing her long-dormant skills as a mechanic.) For the most part this has gone, if not smoothly, then at least pretty well in the end. Maggie and Hopey both seem less prone to disaster than ever before, as does Ray. Yes, Izzy had a fairly spectacular flame-out–literally!–but Ghost of Hoppers nonetheless ended on an optimistic note for her future. Put it this way: No, I wouldn’t be surprised if that was the last we saw of her, if she were lost to mental illness and to us forever, but nor would I be surprised if she came back reunited with her man in Mexico, content and writing again. Penny sort of exploded her way out of the series too, depending on how much credence you give “Ti-Girls Adventures Number 34,” but her story also ended on a note of hope for future reconciliation with her children and repentance for her life of fecklessness. A few years ago, Jaime ended Love and Rockets Mark II with two dueling stories of people making other people feel whole again by virtue of their very presence. What a kindly pair of comics,” I said.

So much for kindness.

The suite of strips that Jaime contributed to this year’s Love and Rockets: New Stories volume, which revolve around the long centerpiece “Browntown,” comprise the cruelest and story he’s ever told. Sadder than “The Death of Speedy,” scarier than “Flies on the Ceiling,” crueler than “Wigwam Bam.” Jaime’s line, which has been loosening somewhat over the course of the last few books (I first noticed it in “La Maggie La Loca”–a de-tightened approach to better accommodate Steve Weissman’s colors), is as limber here as I’ve ever seen it, the closest perhaps he is capable to looking like he drew something in a white heat. In filling in one of the biggest remaining gaps in Maggie’s backstory, the two years she spent living with her family away from Hoppers, Jaime reveals what seems like the key piece of the puzzle of Maggie’s bad luck in love and her punk-era rebelliousness, and a sealed-off well of pain caused by her estrangement from her family. But worse–and I don’t want to spoil anything here, so I’m not even going to say who I’m talking about–it introduces a character who, at long last, can’t come to terms. What happened in this person’s life, through no fault of anyone but the perpetrator but as a result of unwittingly malign neglect by everyone else, broke them, never to recover.

It’s easy enough to tell that sort of story, I suppose, but difficult to make the reader feel an impact of discovery of this tragedy commensurate to what the characters themselves might feel. Jaime’s genius is that he pulls it off, with an out-of-nowhere punch-to-the-gut revelation that literally made me gasp out loud. It’s his “I did it thirty-five minutes ago.” And ever since I read it, when I think of it, I just keep thinking to myself, “Poor [name]. Poor, poor [name].” It makes me want to cry! Cry for an imaginary person I’d never read about until a few pages earlier. (It’s the flipside of feeling proud of the entirely imaginary Hopey Glass for becoming a teacher’s assistant, I guess.) Such power! Between this and the not at all dissimilar ACME Novelty Library #20, this year has featured two of the most devastating–and I mean so sad it impacted me physically–comics I’ve ever read. I will never forget reading this book. Finally, I was there.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #1-2

October 22, 2010Love and Rockets: New Stories #1-2

featuring “Ti-Girls Adventures Number 34”

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2008-2009

104 pages each

$14.99 each

This is going to sound a little weird, but one of my favorite things about the superhero flight of fancy with which Jaime inaugurated this third Love and Rockets series, now in bookstore-friendly post-altcomic squarebound format, is the fact that I was pronouncing the titular super-team’s name wrong nearly the whole time. I was thinking “Tee-Girls”–maybe you can blame the aging super-version of Xochtil’s resemblance to Maggie’s Tia Vicki for putting that pronunciation in my head–when as it turns out its a play on “Tigers.” And whaddayaknow, just like that, Jaime’s imaginary team of misfit superheroines fits right into the very real and very long legacy of superhero characters and creators I’ve heard people completely mispronounce: Namor the Sub-Mariner, Magneto, Sienkiewicz, Quesada, Byrne–not to mention “Jamie” Hernandez himself. Probably just a fluke, I know, but somehow it feels more like attention to detail.

It’s easy to dismiss “Ti-Girls Adventures Number 34” as precisely that sort of pleasant superhero-nostalgia diversion, a chance for Jaime to work directly in the idiom of one of his greatest but least frequently expressed influences. It’s certainly difficult to square it with the Locas-verse as we know it. The wildest left-turn back into the fantastic that the “Locas” strips have taken in probably 20 years, it transforms Penny Century into the mad superhero she’s always dreamed of becoming, reveals that Maggie’s apartment-complex neighbors Alarma and Angel are secretly superheroes themselves (we’d already caught some glimpses of Alarma in costume, but that was in the storyline where we also saw the devil take the form of a levitating black dog, so, y’know, grain of salt), brings sundry superheroes mentioned in the imaginary comics Maggie reads to life (e.g. Cheetah Torpeda, herself the namesake of a strip club Ray D. frequents), features inexplicably aged versions of previously existing characters like Maggie’s wrestler cousing Xochtil, posits the existence of a mutant-like female-only “gift” of superpowers, and ultimately reveals that Penny was never really real to begin with. “I’ve known Penny for quite a few years now,” Maggie says, “and in all that time she never aged. Like, she was not regular flesh and blood, but like, this drawing that was clipped from a comic book and pasted down here on Earth.” And here I’d thought she’d just used H.R. Costigan’s billions to have a lot of work done!

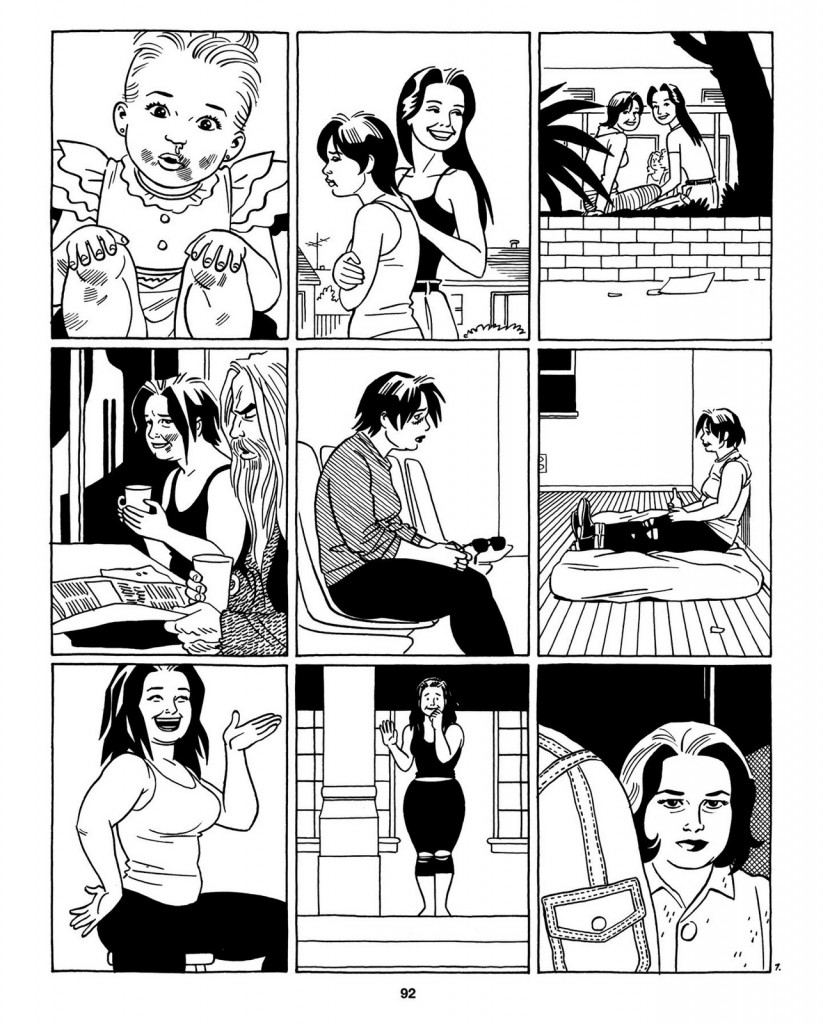

And indeed, Jaime’s art here is so zesty that maybe a chance to have fun with super-powered women in skimpy costumes really is the main point. (And frankly it’d be worth it if only for the debut of Alarma’s glam-rock cut-off-tank-top villain look. Yowza.) The effect he achieves with his black-and-white-uniformed Amazons flying around or smacking each other around against the night sky or in the void of outer space is frequently breathtaking–my dream comic con panel is a “spot-black-off” between him and Mike Mignola. Meanwhile his action choreography is to die for. Witness the knockout wordless nine-panel-grid page in Part Two of the story, featuring a series of images in which Angel attempts to join the fight against an off-the-right-hand-side-of-each-panel Penny Century, only to be rebuffed at each stage by one of the uber-powerful popular girls of the superhero scene, the Fenomenons. In each panel there’s a palpable drive from the left to the right, thanks to motion lines and those blacks, but there’s always something stopping Angel from getting to that elusive border. I know I lecture superhero writers and artists all the time about how they should be doing their job, but, well, this is how they should be doing their job.

But there is more to “Ti-Girls” than meets the eye. Super-Penny turns heel not just because she’s gone mad with power, but because those powers have caused her to lose two of her children; in order to thwart Penny, one of the Ti-Girls uses a ray-gun to zap another with a sample of Penny’s “maternal instinct,” which can be used as a homing device. I think this may be one of the most explicit explorations of motherhood ever for “Locas”; certainly Penny and Hopey’s dueling pregnancies way back when weren’t explored in terms of how the pair felt about the kids they had and/or didn’t have. There’s Tia Vicki’s misery over her belief that Maggie resents her for how she raised her, too, but that didn’t involve birth and babies and very young children like this storyline does. I wonder what it says about Maggie that this is all being processed in something very like a dream?

There’s also an explicit feminist angle. Women are the only people capable of becoming super-powered naturally; they’re born with “the gift,” while men have to try to recreate it with lab accidents or magic meteors or what have you. Meanwhile, the entire history of female superheroes in this world is one of their management and exploitation by one Dr. Zolar–his crowning superheroine-team creation is an all-teen unit, the Runaways to his Kim Fowley. But perhaps most strikingly, certainly if you read regular superhero comics, is what a non-presence male superheroes are. None are drafted into the fight against Penny, and the few we meet are basically non-entities who exist to get thrashed by one of Penny’s super-kids or to help out the Ti-Girls in locating them. The problems in the story–Penny’s rampage, a breakout at a female supervillain penitentiary, a supervillainness out for vengeance, a Bizarro Ti-Girl–are all caused by women, addressed by women, solved by women, and have consequences felt by women. I actually think you might have a hard time getting this comic to pass a reverse Bechdel Rule, in fact. And that’s enormously, enormously refreshing. If “Locas” has taught us anything, isn’t it that women should be the stars and driving forces behind their own damn comic, even if they’re dressing up in one-piece swimsuits and punching each other in the process?

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

October 20, 2010Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

featuring “La Maggie La Loca” and “Gold Diggers of 1969”

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

56 pages

$4.50

(First, a quick reader’s note: At this point I’ve read all of the all-Jaime/Locas L&R collections. For this, the final issue of Love and Rockets as a comic-book-format periodical, and for the three currently available volumes of its new squarebound incarnation, Love and Rockets: New Stories, I’m going to be reading and reviewing Jaime’s stuff on its own before starting over at the beginning with Beto. There are other ways I could play this, but I’m enamored by the idea of being all caught up with Maggie and company. And yes, this means LOVEMBER AND ROCKETS is on its way…)

The triumph of the continuity! Leave it to Jaime to use “La Maggie La Loca,” the inaugural strip for The New York Times‘ “Funny Pages” lit-comics section, to address one of the oldest, wildest, most sci-fi strips in his series’ history. Though the more outlandish details are largely (but not entirely–I spy a glowing robot head in one of those flashback panels) elided, Maggie the Mechanic’s adventures in the jungle alongside Rena Titanon and Rand Race are officially not retconned. I’m happy about this because I’m the sort of person who pulls for that early sci-fi stuff, encouraging folks who want to start reading the series to start there even though it’s so different in vibe and visuals from what it ends up being. I’m also happy because it means that Maggie’s translator for that time, Tse Tse, returns for the strip, revealing herself to have become maybe the smartest and most successful of the characters. (I’d always considered her the “lost Loca” and hoped she’d somehow find her way to Hoppers or the Valley.)

The strip’s story involves Maggie receiving an invite to come visit Rena on the private island where she hides from the admirers and enemies she made during her dual careers as a wrestling champion and a revolutionary icon. Maggie, of course, is just a humble apartment manager, and she spends most of the visit alternating between awe, jealousy, and contempt for her hostess, whose glamour and strength appears to have slowly edged into isolation and paranoia. But what makes the strip really worthwhile in terms of how it relates to the Locas strips of the here and now can be summed up by one panel: A nude, 40-year-old Maggie, standing with her back to us in all her craggy, doughy, Rubenesque magnificence, looking out the window at Rena, her back also to us, arms akimbo, her 70-plus-year-old back and arms still seeming hewn out of wood despite her age, staring down at gifts left by her devoted fans. But as that mirrored pose indicates, both women have essentially the same plight: To what extent are they comfortable with their achievements? To what extent can they let the people they love into their lives? To what extent are they just standing there alone–or is the important thing that they’re looking at people who care about them? Maggie may just be an apartment manager anymore, she may now get in way over her head (literally) when she attempts to have a fun island adventure like she used to, but the way Rena sneaks into her room at night just to watch her sleep reveals that the aging heroine could use a dose of the community and camaraderie that’s part and parcel of Maggie’s dayjob. A life spent fighting people in the ring and the streets has left her admired but alone; Maggie’s misadventure teaches her it’s okay to focus on the former to ameliorate the latter.

Accompanying the main strip is “Gold Diggers of 1969,” a flashback strip drawn in Jaime’s Sunday-funnies kiddie-comic style and concerning li’l Maggie as she bounces between her three other mother figures–her actual mom, her Tia Vicki, and her babysitter/mentor Izzy from back in her wannabe-gangsta teenage years–on a particularly dramatic day. Again we see the ways in which these strong women are weak (I was particularly tickled by the revelation that Izzy’s not a founding member of the Widows at all; sorry, Speedy), and the ways in which they draw strength by helping to protect people weaker than they. Little Perla’s way too young to really notice any of this, but I think that’s the point–flash forward about 15 years when she’s off gallivanting with Rena in the jungle, and she’s still mostly too besotted with hero worship to notice the toll Rena’s glamourous, dangerous life has taken on her. In much the same way that connecting with her new baby brother and her mom and dad makes young Maggie feel like part of a whole, so too does her semi-disastrous visit to Rena at age 40 help give a hero her strength back. What a kindly pair of comics.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: The Education of Hopey Glass

October 18, 2010The Education of Hopey Glass

(Love and Rockets, Book 24)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2008

144 pages, hardcover

$19.99

The “all growns up” phase for the Locas continues. Looking back, the material collected in Penny Century was sort of the calm before the storm for our heroes and heroines–the point at which they’d matured, but the point before they realized they’d matured and started struggling with it. If Ghost of Hoppers was Maggie’s confrontation with adulthood, The Education of Hopey Glass serves up the equivalent for Hopey and Ray. It’s fascinating to me to see where their lives have taken them versus where they were–and more importantly, what they represented to Maggie–when they were first juxtaposed. For starters, this is a really weird and kind of silly thing to say about a comic book character, but I am straight-up proud of Hopey for becoming a teacher’s assistant. (Waiting for Superman can go pound sand.) It reveals a strength of character she’d always kept carefully hidden, an indication that beneath the hellion exterior, she’s actually, well, a good person, a person capable of caring about someone other than the Maggot. What’s refreshing about what Jaime is showing us here is that this in no way “fixes” Hopey, nor makes her suddenly respectable. She’s still a loudmouth bartender and an incorrigible womanizer with a wandering eye, and she still can’t seem to help but hurt the people who care about her. And on the more positive side, she’s still sexy and funny and badass and all the other things that have made her fun for her friends to be around. Her new job in a position of responsibility isn’t something she sacrificed the person she’d always been to achieve. Like the glasses she spends the storyline shopping for, it’s just a new accessory on the same old face, a new way of looking at things with the same old eyes.

Good ol’ Ray Dominguez, on the other hand, is more ol’ than good at this point. The rumpled, cigarette-smoking noir narration we encountered from him last time around is back with a vengeance, and the succession of endless nights of booze, broads, and loneliness it suggests tells us that much has changed over the nearly two decades since he first emerged as the safer, more caring alternative to Hopey in the quest for Maggie’s heart. This is not to say that he’s the full-fledged devil-may-care degenerate of the sort comprised by the circles his old friend Doyle and his would-be flame Vivian “The Frogmouth” Solis move in–on the contrary, his relentless narration is a litany of worrying that he’s too old, a given situation too hairy, a given woman too much trouble, a given dude too dangerous even to know. And yet through some innate inability to really stick up for himself and go for what he wants, Ray is constantly buffeted from predicament to predicament by the still more fucked-up people with whom he surrounds himself–a classic noir patsy protagonist, played mostly for Lebowski-style black laughs. Ray wonders aloud why he’s so fixated on the two years he spent with Maggie all those years ago, especially in light of what he eventually gets going with Viv, but it feels like less of a secret to us: He saw what he wanted and hung onto it. My fear is that the Frogmouth is too much of a (hilarious!) human disaster area to give him the gumption to do so this time around, but anything’s possible, and he seems to realize that it’s now or never.

What makes these two stories compelling and connects them to one another beyond the basic idea of the characters coming to terms with their age is how much the stories rely on the kinds of things only an artist of Jaime’s caliber can pull off for their telling. Hopey’s many loves and crushes–Maggie, Rosie, Grace, Guy Goforth, Angel, the woman at the eyeglasses store–are woven into an intricate web of eye contact and body language, glances and looks away, the clothes they choose to wear and what they look like naked. Half the story emerges from characters looking at how other characters look at still other characters. Ray’s story, meanwhile, takes place about 30 feet in front of a murder mystery, if you will, one that he and his friends remain half-aware of and half-willfully oblivious to as it approaches, takes place, and ripples out into its aftermath. As Ray does his thing, we’ll see people behind him start arguing and fighting, whisper to one another, disappear and reappear, shoot daggers at one another or look sheepish and sick. Ray putting it all together is one of the catalysts for him trying to get his own act together by the end of the story–and it wouldn’t have been possible if Jaime hadn’t been such a poet of bar fights and parking-lot conspiracies in the rear of the panels. Maybe adulthood isn’t just choosing a new way to see with your same old eyes, but also choosing not to look sometimes, too.

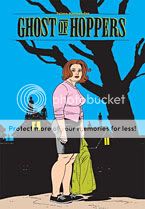

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Ghost of Hoppers

October 15, 2010Ghost of Hoppers

(Love and Rockets Book 22)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2006

120 pages, hardcover

$18.95

Jaime Hernandez has long displayed an infrequently utilized but alarming alacrity for horror. The Locas comics’ outbursts of genuine violence have been scary–I’ll never forget Hopey getting stomped on in the bathtub and staggering out, leaning naked against the door frame, or Speedy half-lit by the streetlight, a portrait of a young man at the very moment he hits rock bottom that chills me to my very soul. But in general the real terror, the real exercises in creating and sustaining horror imagery, emanate from Izzy Ruebens. Maggie and Hopey’s long-suffering, eccentric mentor has slowly withered, almost, over the years, from the semi-comical parasol-wielding goth of the strip’s early, punky days to the stoic, emaciated, frequently naked presence we’ve seen in Penny Century and now Ghost of Hoppers. Whether she’s simply mentally ill or genuinely haunted (and the two aren’t mutually exclusive possibilities, to be sure) is almost immaterial. In either case, the danger comes simply from seeing what she sees. The shadows, the stains, the shattered and inverted crucifixes, the black dog, the flies on the ceiling–these are monumental horror-images, frightening not because of some physical threat they present but the violation of reality they represent. They’re frightening by virtue of their very existence. Something is wrong with them. All of the damage they’ve caused–and based on what we know of Izzy’s guilt over her abortions and suicide attempts, the damage that caused them–has been self-inflicted.

At first I struggled with why Jaime would choose this particular storyline–Maggie Realizes She’s All Grown Up, basically–to delve deeper than ever into this aspect of the Locas world. I mean, this thing becomes a horror comic toward the end, easily the most sustained such work in the whole Locas oeuvre. What does any of it have to do with the misadventures of Maggie, the story’s protagonist? But then it clicked: She, too, is threatened here by the violation of her conception of reality. Is she the badass punker she always thought she was, or has she grown up to be a square like everyone else? Is she basically just a fun-loving straight girl with one exception that proves the rule, or might she be physically and emotionally attracted to other women after all? Is she okay with the friends-with-benefits relationship she’s had with Hopey since time immemorial, or does she want something more? Were she and Hopey really the center of the universe, or were there equally vibrant and vital relationships that continued on without them? Can she maintain her self-image as a troublemaker when she’s at a place where she really kind of hates trouble? Does Hoppers–her neighborhood, her hometown, her group of friends and fellow travelers–still exist in her mind as a screwed-up but happy place to visit, or has the passage of time rendered that all a lie? No wonder the black dog chooses now to pay her a visit. She had so much to be frightened of already. Thank goodness that life sometimes grants even hapless Locas an exorcism or two on the house.