Posts Tagged ‘LOVE AND ROCKTOBER’

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

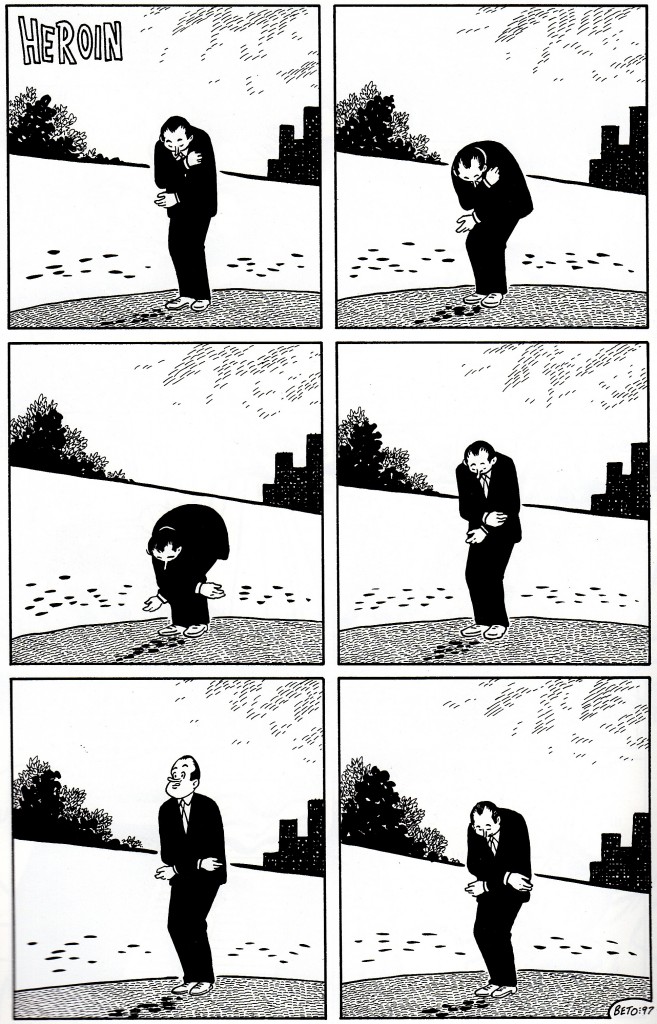

July 15, 2012Gilbert and Jaime are both masters of the form of comics. That’s in addition to their character work, their sheer illustrative chops, and so on; indeed it may be the most exciting thing about them. In the case of both brothers I’ve spent a long time chewing over just a few handfuls of panels, unpacking what went into them. Here’s Gilbert’s silent, six-panel comic “Heroin,” one of three one-page shorts he made with that title. It’s just a man against one of Beto’s soon-to-be-trademark dismal nowherescapes, clutching his arm, doubling over, standing back up, hunching over again. We don’t know who he is or where he is or what he’s doing or what its connection is, specifically, to the titular substance — he could be a junkie on the nod, sure, but then why is he also Richard Nixon (or maybe it’s Bob Hope)? Whether it’s about the drug specifically or addictive, destructive influences generally (as are the other two “Heroin” strips) doesn’t really matter, since the effect stems almost entirely from the building blocks of the comic itself: the man, the background, the grid layout, the lack of any text save the title, the rhythm that builds up as we watch his body contort, the three big blocks of black in each panel (trees, man, buildings), the hands pointing in opposite directions, the diagonal hill line bisecting each panel. Every element combines to convey discomfort and unease, the sense of being at the mercy of something that lets you straighten out just long enough for it to be crushing when it knocks you back down. Long before I’d actually read any comics by Los Bros I saw this page reproduced in an issue of The Comics Journal and it has worked its way into the fabric of my comics brain ever since. It occurred to me just the other day that I’ve even done a homage to it without realizing it. I think it’s a perfect comic.

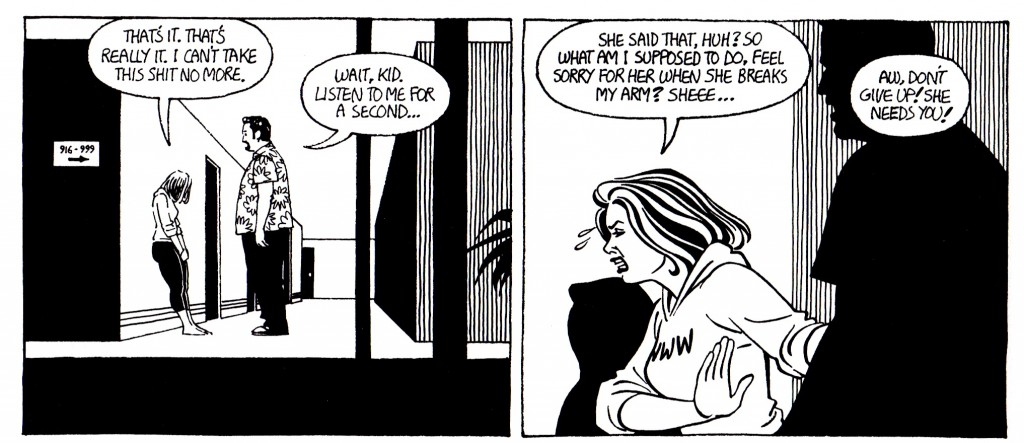

And here’s two panels from “In the Valley of the Polar Bears” by Jaime. Maggie’s been working as the kayfabe “accountant” for her wrestling-champ aunt Vicki, something of a terror in and out of the ring, but the two are barely speaking. Vicki has just confided in her wrestler boyfriend Cash that the reason she’s been treating Maggie so badly is because she cares about her a lot and is hurt by Maggie’s seeming indifference in return. So here, Cash approaches Maggie to tell her about her aunt’s secret soft spot — and then blam, next panel, it’s already been told. Jaime doesn’t show us the conversation. He doesn’t slap a big “Five minutes later…” caption up there. He doesn’t alter the size of the panels or the gutters to imply the passage of time. He doesn’t cut to another scene in between. He doesn’t show Maggie and Cash in another location so that we’d know time must have passed for them to get from place to place. He zooms in a bit but other than that they’re even in the same basic spatial configuration. He pretty much breaks every rule of how jumps in time are conveyed in comics, and yet it’s still crystal clear what happened. Talk about no-fat storytelling. Why belabor the re-presentation of information we readers already have? And why monkey with shit to explain what you’re not showing us when you can simply not show it to us and assume we’re smart enough to follow? These two panels are so bold, so full of lessons in how to tell a story with comics. I think about them all the time.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

July 14, 2012Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez have each been telling the stories of the same group of characters, continuously, for three decades. They’ve done lots of other stuff, Gilbert especially, but that’s the bulk of what they’ve done. No one else in comics has done it. No one’s even come close. Could someone else do it? Could someone else tell the life story of their characters, over an actual life span, and have a lot of people care passionately about where those lives end up? I won’t say it’s unimaginable, the idea of someone else doing it, because there are enough similar cases out there for you to imagine those other people doing it, and it’s only then that the gulf between Los Bros and everyone else becomes so clear. What if Bryan Lee O’Malley just kept going with Scott Pilgrim until he hit Vol. 30? What if Dave Sim had never lost his mind? What if all the B.P.R.D. spinoffs were written and drawn by Mike Mignola? What if Achewood were a comic book and Chris Onstad never burned out on it? What if Erik Larsen’s main touchstone for Savage Dragon were Márquez rather than Kirby? What if The Walking Dead were filled with Rick-level characters, instead of Rick and a bunch of other people for Rick to react to? What if Alison Bechdel made a series of Dykes to Watch Out For graphic novels instead of memoirs? What if Harvey Pekar had made stories up instead of writing them down? What if all of these things lasted for thirty years? And oh yeah, what if all of these people had siblings doing the exact same thing at the same time under the same title? It’s only when you see all the hoops one would have to jump through even to come close to what Beto and Xaime have accomplished that you really appreciate that hey, they’re the ones who built the hoops.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

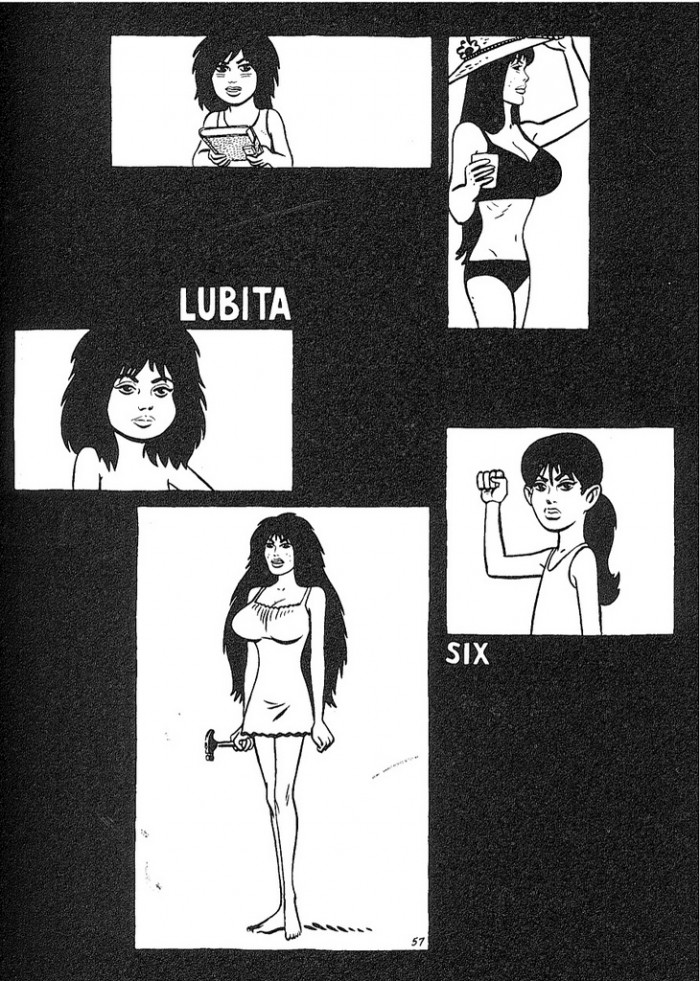

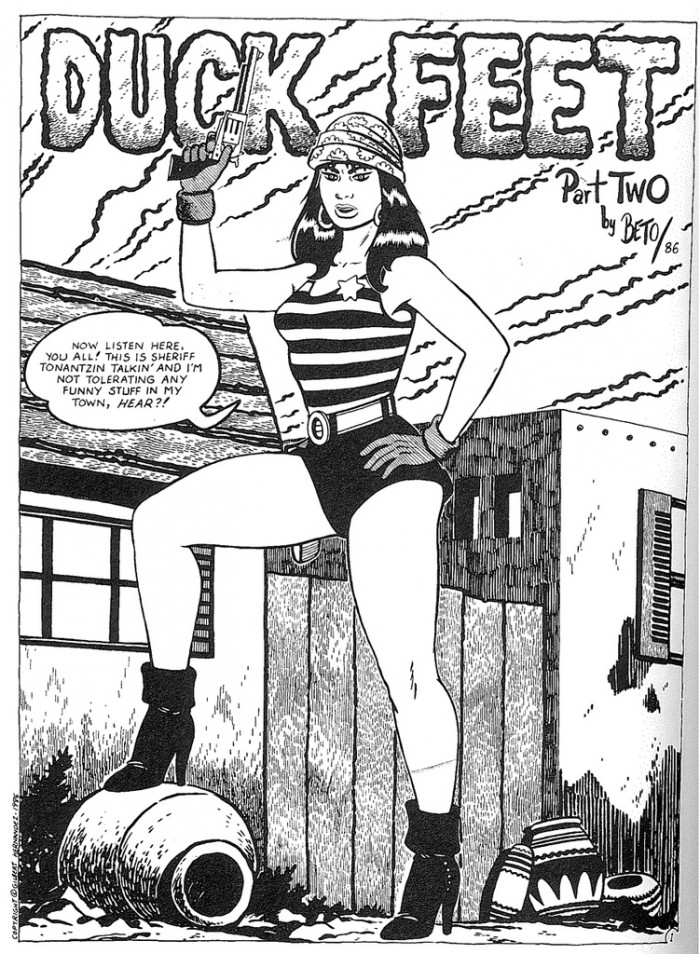

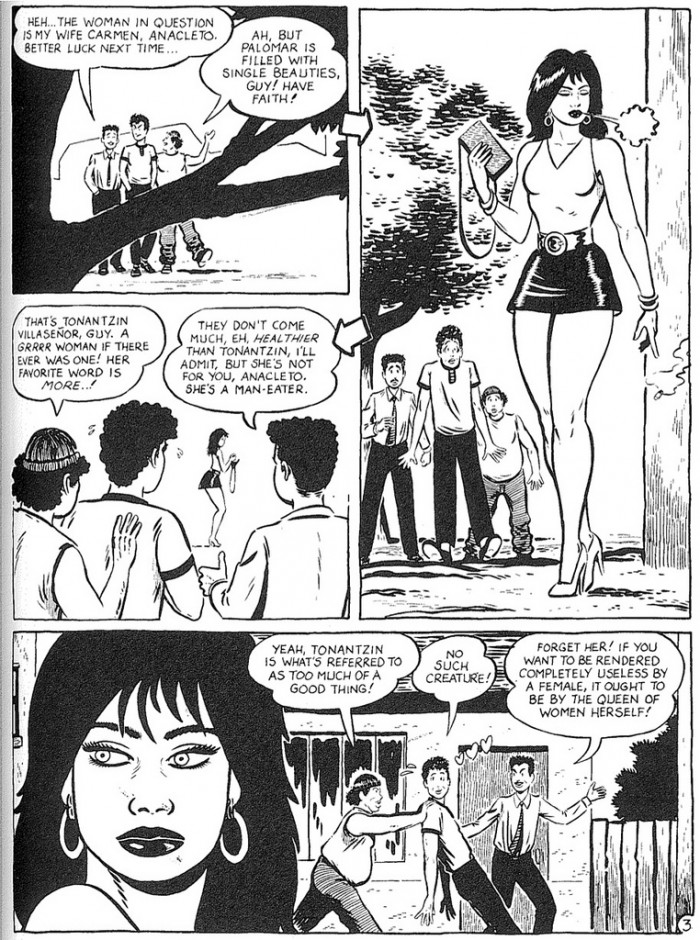

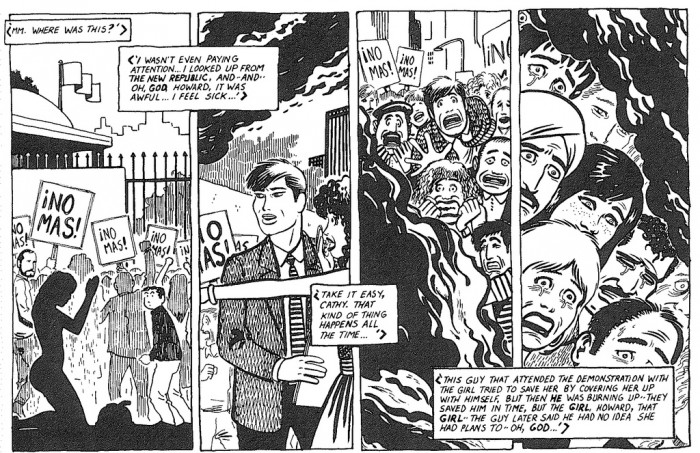

July 13, 2012Any character in Love and Rockets stands a decent chance of being my favorite on any given day, because they are designed to be contemplated, and I’m the contemplative type. Today I’m thinking a lot about Tonantzin, one of the stars from Gilbert’s Palomar stories. She’s a stunningly hot small-town girl, so her rebelliousness first manifests itself by dressing provocatively and using sex to self-actualize. But her mind, heart, and psyche are all as dangerously overdeveloped as her body and sensuality, she gets swept up in a series of increasingly destructive obsessions, first with America and Hollywood, then with native culture and political protest, then with the danger of militarism and the possibility of nuclear annihilation. We can see that they all provide her with an emotional and intellectual way out of the confines of Palomar and her own body — indeed things start getting really bad when she’s taught to read — but because he never really describes it as such, we never realize how far she’s willing to go until it’s too late. Ultimately she comes to believe the only truly free intellectual and political act is to destroy the body she came in. It’s an unforgettable and utterly unique portrait of how good ideas and good people can nevertheless combine into something very bad. It’s a lesson that life entails losing vibrant, lovely people you neither want nor expect to lose. It’s a tragedy for a young woman and the people who love her. It’s a commentary on the hopelessness of the political climate of the day. Today I find myself wondering whether if she’d grown up in Hoppers instead of Palomar, and had punk and the Locas as a release valve instead of abnegative protest, would she still be alive today? On the flip side, would Speedy Ortiz still be alive if he’d grown up in Palomar instead of Hoppers, in a place where it was easier to form romantic relationships and harder to form ones based on a shared propensity for collective macho violence? This is the kind of thing you could do all day long with character after character after character from both Gilbert and Jaime. They’re drawn to be viewed from all angles.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

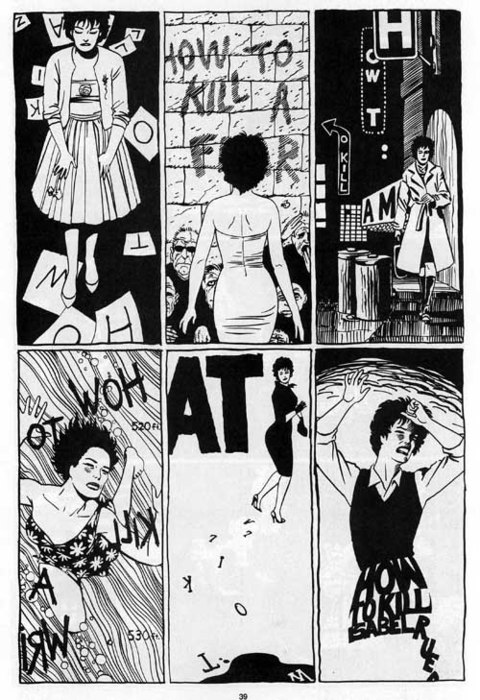

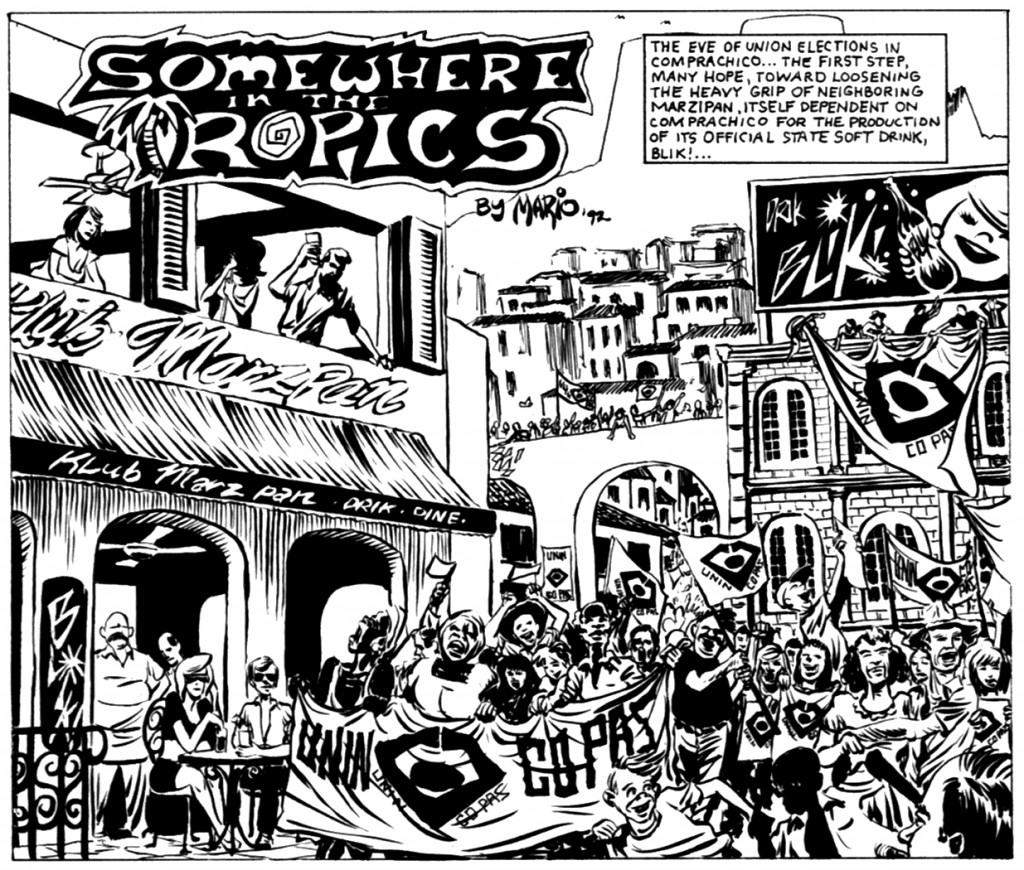

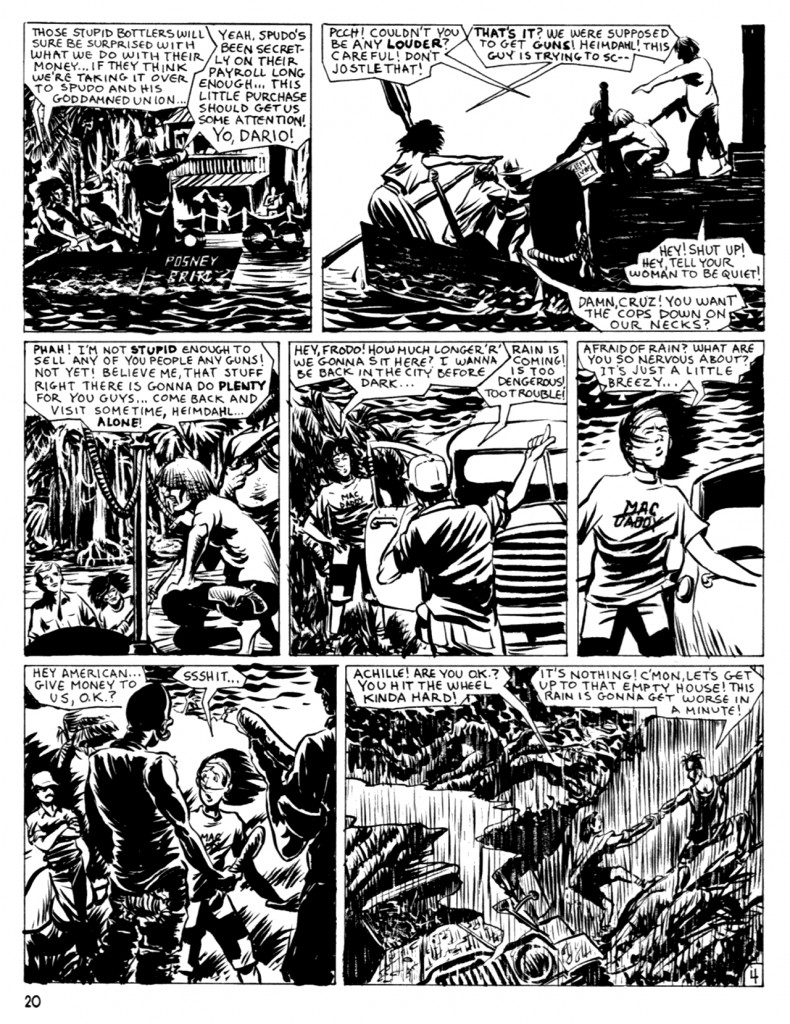

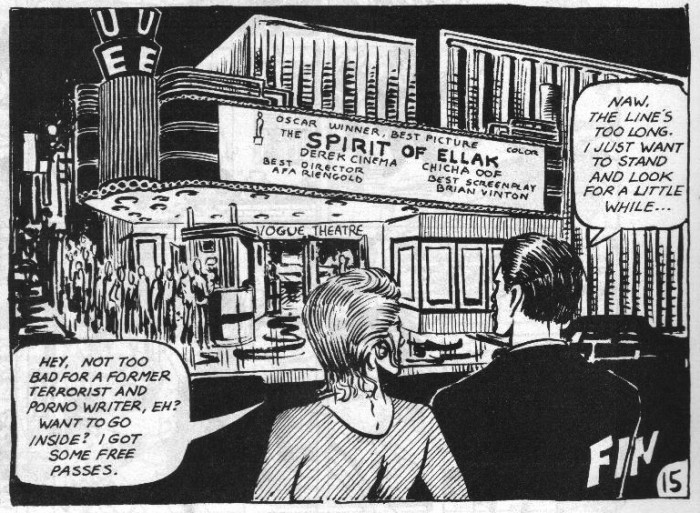

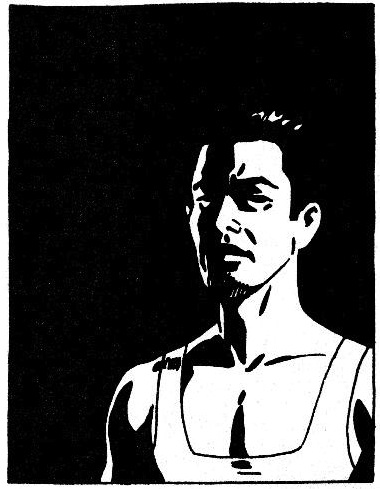

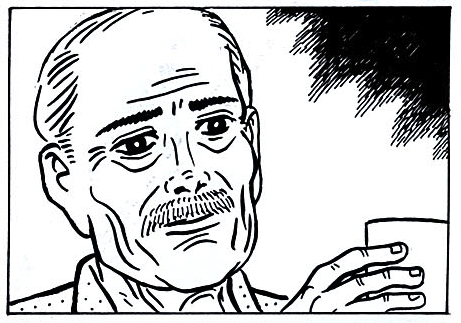

July 12, 2012Mario Hernandez is the great lost alternative cartoonist, the Lost Bro Hernandez. His interest in cosmopolitanism, leftist politics, the conflation of activism and terrorism by the authorities, the pas de deux between terrorism and authoritarianism, the revolutionary and counterrevolutionary power of art and pop culture, the Third World as a petri dish for first-world government’s reimportation of radicalism, all within the framework of vaguely science-fictional thrillers — he is in many ways the perfect comics-maker for our present moment. With its heavy use of blacks his style sits comfortably alongside those of his brothers, but its density and its bold slashing brushstrokes set it completely apart. If he’d had the time or inclination to produce the same volume of work, published with the same regularity, as his brothers, we’d likely have a third pantheon-level creator from the same generation of the same family, an astonishing thing to contemplate. As it stands we have a hidden treasure, a single gem in a stack of gems, and that’s not so bad either.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

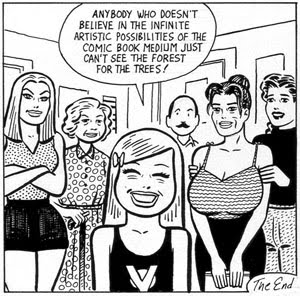

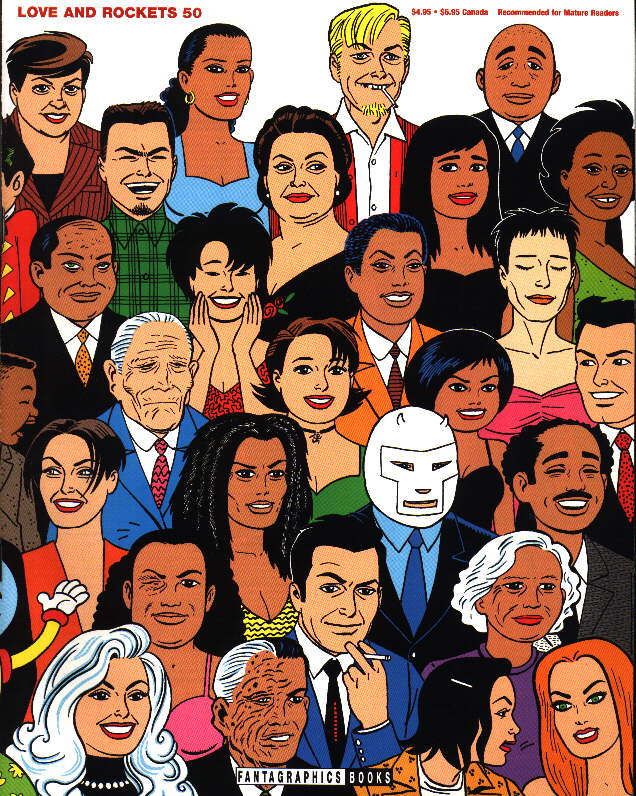

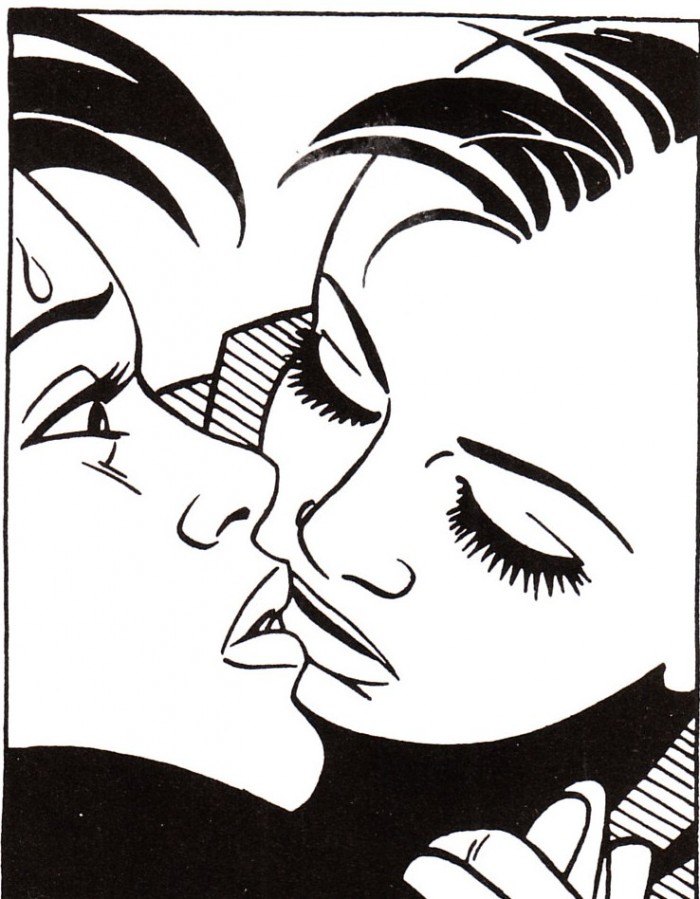

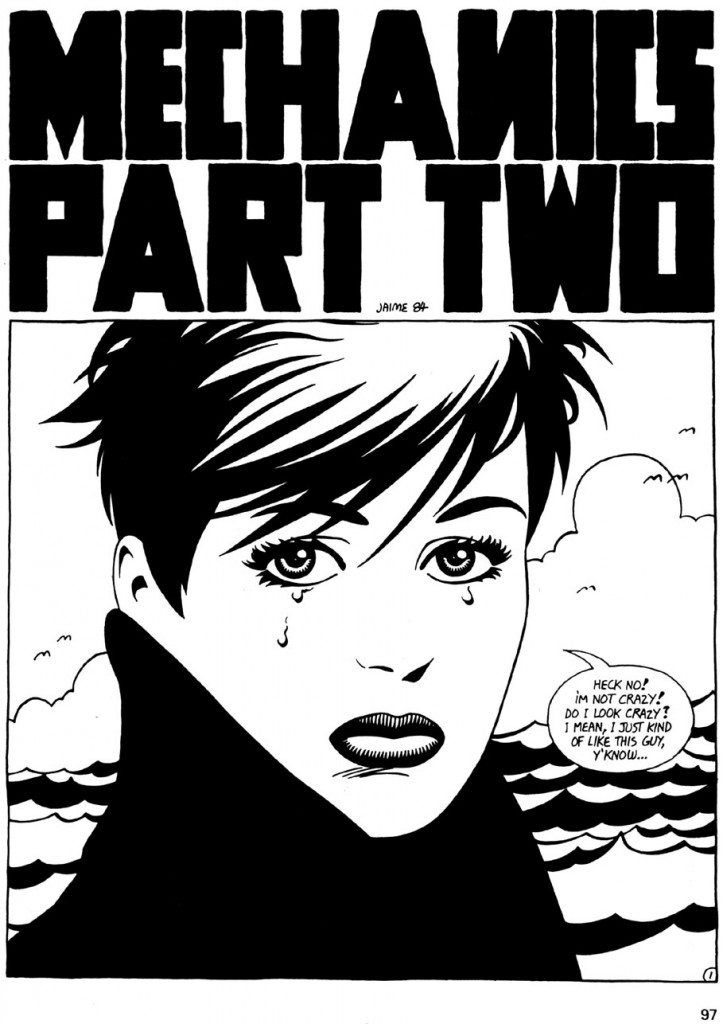

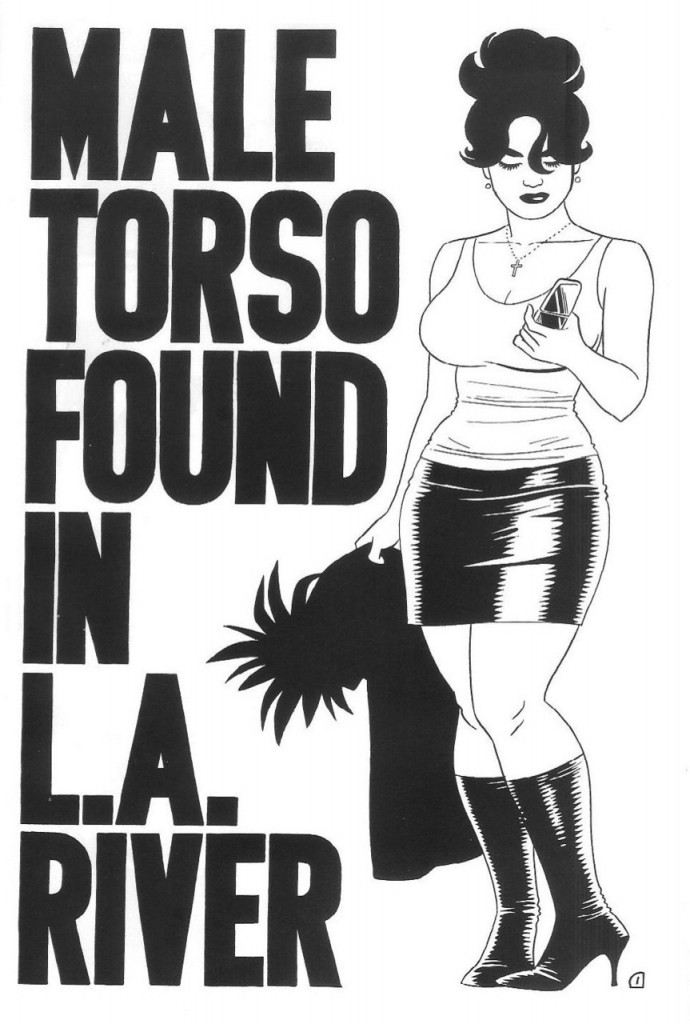

July 11, 2012Jaime Hernandez is comics’ greatest maker of standalone images. His blacks, his typography, his sense of style, the drama of his line, the sense of balance and momentum even within a single image, his use of powerful moments to convey character, the whole nine. Out of all his peers in the ’80s and ’90s alternative comics movement — the stuff I think of as High Alt, the solo anthology series cartoonists who eventually coalesced around Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly, Xaime and Beto and Ware and Burns and Clowes and Brown and Doucet and Bagge and Tomine and Sacco and Woodring and French — his makes him uniquely suited for the Tumblr era, when the rebloggable, context-free image is king. As such he stands the best chance of elbowing his way into the new canon currently being established as a reaction against High Alt and its forebears, consisting mainly of high-impact, visually dazzling genre comics whose work thrives in a one-at-a-time context — Kirby and Moebius and Otomo and Miller and Chaykin and Manara and pre-alt Mazzucchelli and McCarthy and Graham. But his best images often come within the flow of a story in addition to pin-ups, posters, covers, and title pages, and his interests broaden the canon-of-spectacle beyond solving problems through violence and/or sexy stylishness. They work equally well as vehicles for devastating emotional reveals, or as t-shirts.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

July 10, 2012Outside of erotica and autobiography, no cartoonist has ever woven sex so indissolubly into the fabric of his comics as Gilbert Hernandez, in a fashion reflective of lived experience. In all of fiction comics, only writer Alan Moore comes close. This goes beyond simply drawing hot people, although before unfortunate circumstances intervene, Tonantzin and Khamo are probably the hottest woman and man in all of comics. Gilbert’s ability to describe and depict physical attraction between his couples frequently makes for the sweetest and most romantic aspects of those relationships—whether male or female, characters’ appreciation for their partners’ hips, tits, dicks, thighs, stomachs, faces and what-have-you, and for the pleasure those parts bring them, is often just plain adorable, however freaky or kinky or dirty things might get. But Beto’s larger argument appears to be that we can no more separate our physical desires from our lives than we can detach from our physical bodies in the course of living them. This of course has a dark side: Life is frequently terrible, and thus so is sex in Gilbert’s comics. And so his greatest creation, Fritz, is the em-body-ment of all these aspects of Beto’s work: She is the sweetest, sexiest, kinkiest, dirtiest, most tragic character of them all. There are no sex scenes in Beto’s comics—life is a sex scene, for better and for worse.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

Your Love and Rockets 30th Anniversary thought of the day

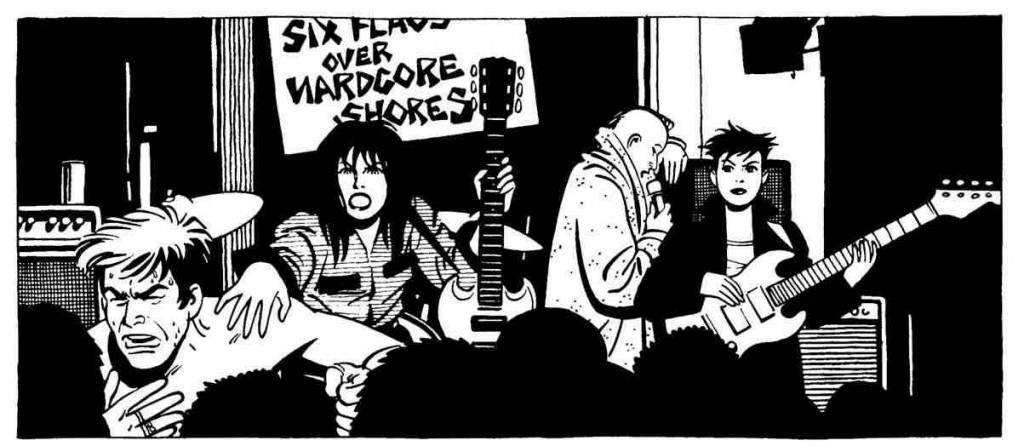

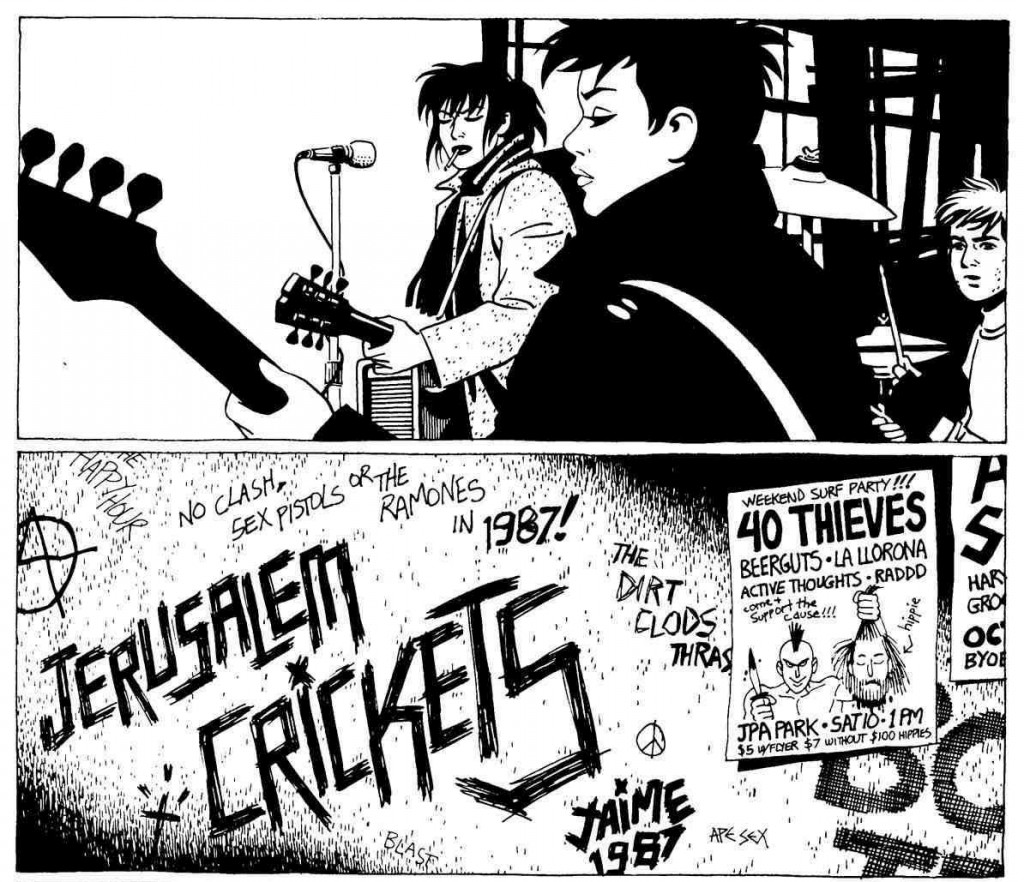

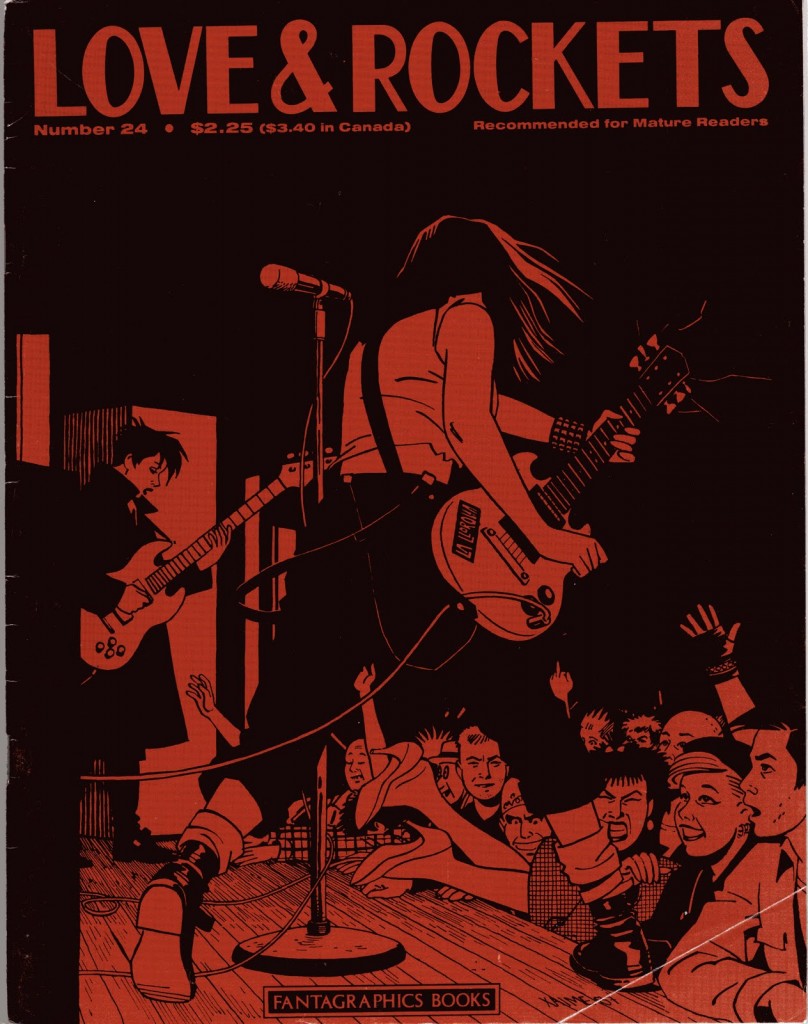

July 9, 2012No cartoonist has ever captured the spirit of rock and roll — listening to it, watching it, performing it, defining your life with it — like Jaime Hernandez. Vanishingly few have even come close; most attempts are cringeworthy. Jaime not only nailed the style, and the intensity, and the specific idiom of his punk milieu (the graffito “NO CLASH, SEX PISTOLS OR THE RAMONES IN 1987!” in the panels below is worth more than entire critics’ bodies of work), and the nuts-and-bolts stuff like the body language of people playing music on stage, he also chronicled the lives of the characters involved long enough to be basically the only cartoonist ever to explicitly examine what it’s like when you grow up and grow older and discover that you no longer look and act and think like someone in the pit at your favorite band’s show.

Love and Rockets, the great serial comic by Gilbert, Jaime, and sometimes Mario Hernandez, is celebrating its 30th anniversary at the San Diego Comic-Con International this week. Inspired by Tom Spurgeon, this week-long, daily series of posts will highlight some of my favorite things about Los Bros Hernandez and their comics. For more information, click here.

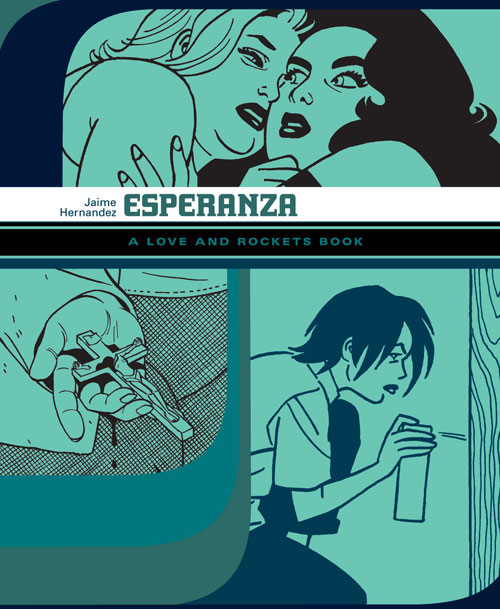

Comics Time: Esperanza

April 4, 2012Esperanza

Love and Rockets Library: Locas, Book Five

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

248 pages

$18.99

Fantagraphics, 2011

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

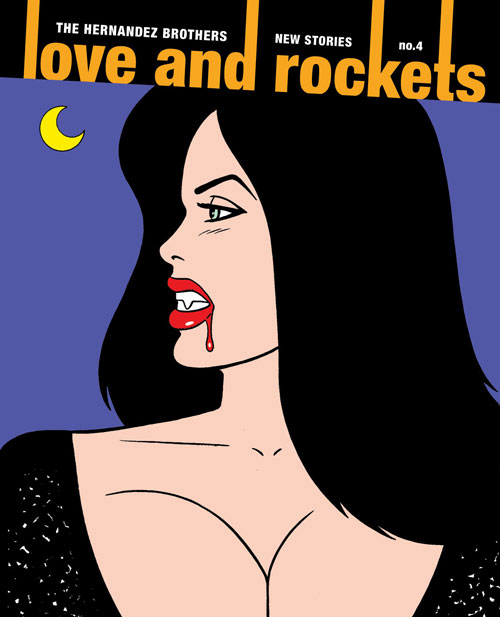

Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

August 1, 2011Love and Rockets: New Stories #4

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, August 2011

104 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

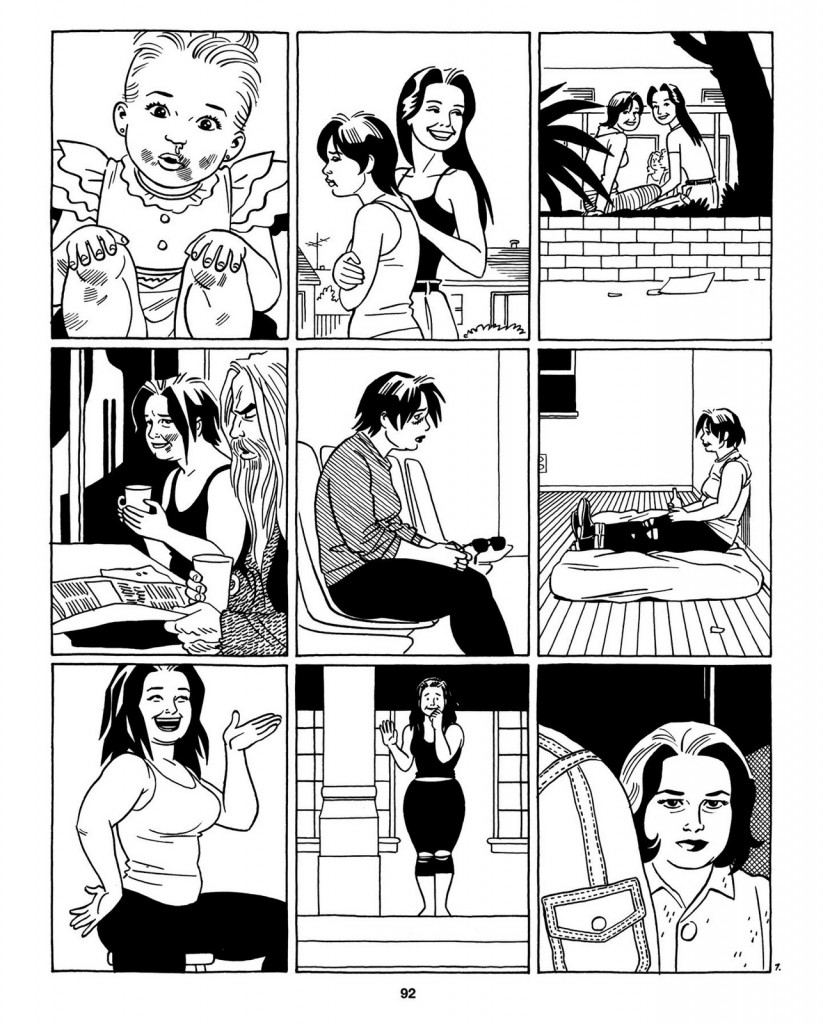

Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 will turn any fan of Los Bros Hernandez into the host of The Chris Farley Show. “Remember? That time? When you drew Calvin’s plaid shirt? So that the plaid was always facing in the same direction? No matter how much Calvin moved?…That was awesome.” I am seriously finding it difficult, if not impossible, to review this comic without simply hitting the bullets-and-numbering button and whipping up a list of everything in it that amazed me. It would be a long list, too. But I’m abstaining as much as I can — to challenge myself for starters, and to avoid spoiling the comic for those of you who haven’t yet read it (which is probably most of you since it’s not out yet) for the most part. But I’m also holding off on that listicle because I think it’s a cheat. The fact of the matter is that while reading this book I discovered that I’m at least as attached to Ray Dominguez and Fritz Martinez, the protagonists of Jaime and Gilbert’s contributions respectively, as I am to a decent number of real people in my life. So sure, I could rattle off the ways in which Xaime and Beto continually prove themselves to be among the most graphically inventive and entertaining cartoonists alive some three decades into their careers — the crosshatching on Ray’s shirt and Maggie’s sofa; Gilbert’s use of wavy, puddle-shaped, impenetrable fields of black in his vampire story; the impact of the just-this-side-of-parallel lines of Angel’s body as she bends her leg to put on a high heel; the upside-down lava-lamp shape of Fritz’s legs in a skirt, used as an anchor for panel after panel of her simply walking around town with her agent ex; dredging up a long-ago, possibly long-forgotten character, drawing him as a late-middle-aged man in a way that makes him unrecognizable until you realize just how recognizable he is; the smashed-skull-as-cubist-masterpiece in Gilbert’s customary burst of horrifying ultraviolence; the holy shit moment when you realize the visual structure to that montage spread from Jaime’s story; Gilbert storming the ramparts of the vampire story and launching sex and violence back into it like payloads from a trebuchet; Jaime serving up a story whose snapshot style echoes comparable material from “Wigwam Bam” in significant and story-relevant ways; tracing the similarities and differences between Killer and Fritz via the characters they play, the use of their amazing bodies fraught with story information. And hey, look at that, I did rattle them off! But in the end, how it looks pales in insignificance next to what happens, because making it look that good is a means to the end of imparting just how much what happens matters. Ray’s shirt and Fritz’s legs, the shadow of the vampire and the structure of the montage — they’re just landmarks to remind you where you were when you found out if Ray and Fritz and Maggie were going to get happy endings, or not. It’s the easiest thing in the world to understand, and it’s the hardest thing in the world to do, and it’s magic, pure magic, to do it this well.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #1-3 and “Dreamstar”

December 8, 2010Love and Rockets: New Stories #1-3

featuring various stories by Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2008-2010

104 pages each

$14.99 each

Buy them for 33% off from Fantagraphics

Buy them from Amazon.com

“Dreamstar”

in MySpace Dark Horse Presents #24

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Dark Horse, July 2009

8 pages

Read it for free on MySpace.com (sorry, the permalink to the story isn’t working so you’ll have to scroll for it)

Buy it in MySpace Dark Horse Presents Vol. 4 from Amazon.com

“Fuck. Where’d all the good sex go? There used to be fuckin’ and sucking’ and pussy eatin’ and everything. Pussy eaten’ being my favorite. Now it’s rare to see sex much lately, unless it’s seen as sad or creepy or simply wrong. Shit, is that a cop?”–from “The Funny Papers”

“I didn’t get naked or do porn or have to suck anybody’s dick!! OK?!!”–from “Sad Girl”

“The naked maniac guys, the bloody cop, my up-the-butt daisy dukes…camera behind me getting a good close-up…I’ll take what I can get.”–from “Killer * Sad Girl * Star”

“They’re only animals! You did it! You did it too!”–from “Scarlet by Starlight”

The suite of stories Gilbert Hernandez contributed to the relaunched, graphic-novel-format Love and Rockets: New Stories might be his most complex work yet. By my count, you have two relatively straightforward strips, “Sad Girl” and “Killer * Sad Girl * Star,” starring Killer, Guadalupe’s teenage daughter and heir to the Luba/Fritz/Petra bombshell genes. You have a Fritz B-movie, “Scarlet by Starlight.” You have a movie Killer starred in, “Hypnotwist,” which was a remake of an earlier film we’re told; two other Killer movies are woven into “Killer * Sad Girl * Star.” You have an abstract strip called “?” with which “Hypnotwist” shares much of its visual vocabulary. You have a strip that’s similar in tone to his bleaker Palomar morality plays, “Papa,” and a similarly cold America-based strip called “Victory Dance.” Then you have a funny-animal goof called “Never Say Never,” an exercise in ’60s-style humor cartooning called “Chiro El Indio” that’s written by brother Mario, a trio of newspaper strips called “The Funny Papers,” and a kill-crazy rampage by the Martin & Lewis impersonators from Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla (seriously!) called “The New Adventures of Duke and Sammy.” Finally, there’s “Dreamstar” from Dark Horse’s defunct webcomics site at MySpace.com, which is still another film from Killer’s oeuvre.

It was only in reading Beto’s stories in all three volumes that the Chinese puzzle-box intricacy of what he’s doing here revealed itself to me. Much of this is accomplished by delaying the point at which we receive vital information. In “Hypnotwist,” we don’t see Killer appear until a pair of pages deep into the strange, wordless strip. Up until then we’ve been focusing on the imagery the strip shares with the previous volume’s “?”–giant smiley faces, a tumbling glass, ducks, a door with a question mark; meanwhile, the meager information about Killer’s first movie we learned in “Sad Girl”–it involved a lot of green-screen work and running in place in a trenchcoat designed to make her look nude underneath–doesn’t tip us off about anything in “Hypnotwist” until Killer herself shows up. “Scarlet by Starlight,” meanwhile, never tips its hand, not even with subtle deviations like the hair-color games Chris Ware played with his similar sci-fi/horror story-within-the-story in ACME Novelty Library #19. Unless you happen to remember the title from Fritz’s strips, or the endpages in The Troublemakers and Chance in Hell, there’s no way to tell it’s a “movie” from the Palomar-verse until you see Killer watching part of it in the following strip. Fritz herself is buried under cat-person make-up and her humanoid speech doesn’t give her lisp occasion to manifest. (I know she has other identifying characteristics, but let’s face it, when it comes to deducing the identity of Beto characters, “giant breasts” hardly narrows it down.) In “Killer * Sad Girl * Star,” one of the movies Killer stars in is presented in such a fashion that it seems to be real life. “Victory Dance” starts out like a non-narrative exploration of figurework a la “Heroin” from Fear of Comics before becoming a story about a relationship haunted by the spectre of death and one member’s fleeing from it a la “Papa,” and finally revealing itself to be set in “Papa”‘s world. “Papa,” meanwhile, could be a Palomar-verse strip for all I know–I’d need to go back and see if mudslides or poisonous worms were ever a feature of Palomar’s surroundings. “The New Adventures of Duke and Sammy” plays “Papa” and “Victory Dance”‘s relationship/travelogue tragedies as farce. “The Funny Papers”‘ sub-strip “Meche” evokes a key backstory element in the Fritz comics, while “It’s Good to Be…” (quoted above in its entirety) seems to be a direct commentary on Beto’s current approach to sex in his comics. As is custom, the films we see the characters acting in are all reflective of the issues of sexuality that dominate their own lives. Specfically, the brutal exploitation of children at the center of “Scarlet by Starlight”–delivered in a grotesquely matter-of-fact panel, savagely angry and awful–is echoed by the far milder but still insidious sexualization of “Killer * Sad Girl * Star” later on in issue #3…and, of course, it compliments and reinforces Jaime’s “Browntown”/”The Love Bunglers” suite in that same volume. All in service of what feels like an extension of the flagellating self-critique we saw in High Soft Lisp, the quotes above being Exhibit A.

And I could probably go on! But to do so would be to imply that trainspotting is the primary value of these comics. I could just as easily enumerate the innumerable pleasures of Gilbert’s cartooning itself in these strips: The wire-thin, unwavering line with which he draws the legs of the protagonist of “Hypnotwist,” say–a style I’ve never seen him use before. That choreography in “Victory Dance.” The emergence of vast, hellish landscapes as a no-doubt-about-it theme in Gilbert’s work with the opening of “Papa.” The dead-behind-the-eyes facial expressions of the humans in “Scarlet by Starlight.” The sequence in “Hypnotwist” where a balloon-headed man’s head is popped, leaving it sagging horrifically off his neck as he crawls in the nude. The WTF repetition of the Masonic square and compass. The unexplained holes in Papa’s head. Killer as a heavy-lidded Luba lookalike. Hector as a wild-eyed gray-haired hot-tempered eminence grise.

All told, you could wrap these stories up between two covers and come up with a book of absolutely crushing intelligence, emotional heft, and visual power–a book among the best of Gilbert’s career. And by #3, Jaime is hitting a similar career peak, playing off of similarly uncompromising themes. Here I am at the end of over two months of reading nothing but going on three decades’ worth of Love and Rockets, and neither I nor Los Bros Hernandez are anywhere near exhausted. All hail.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Chance in Hell

November 29, 2010

Chance in Hell

Fantagraphics, September 2007

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

120 pages, hardcover

$16.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

(Note: I originally posted this review on January 18, 2008. This was before I’d read much, if any, of Gilbert’s Fritz material from Love and Rockets. I think the review holds up, which is why I’m re-running it; but with all of Beto’s post-Palomar Palomar-verse work under my belt now, if anything I find Chance in Hell, both its content and its very existence, even more disturbing. On a story level, the “movie” from which the graphic novel is “adapted” turns out to be a “what-if” for its co-star Fritz (whose prostitute character in it doesn’t have a speaking role), featuring a protagonist whose life easily could have been Fritz’s if her mother Maria had been just a bit more heartless or her father Hector just a bit more awful. But that right there’s the thing: Gilbert basically takes the single worst thing ever done by anyone in any of his stories, turns up the volume on it, and builds a new, even more violent and hideous story around it. “Some carry the pit in them for the rest of their lives,” says the book. And later: “There’ve been people who’ve survived, but each has carried with him a distinct odor for the rest of his life. A unique smell that he could never remove. Like mine. Like the smell I carry and must mask with a special cologne of my own design. Is there something you must mask?”)

—

Rough, rough stuff from the creator of Palomar. Hernandez is in the midst of creating graphic novels based on the B-movies that his Palomar-verse character Fritz starred in, but “B-movie” might give you the wrong impression here. This isn’t one of those howlers the bots made fun of on MST3K–it’s the kind of disturbing, unpleasant film starring and shot by unknowns that you might rent on a whim from the horror or European section of your old neighborhood video store, watch, and spend the rest of the evening worried about the mental health of cast and crew. The story concerns Empress, an orphaned toddler abandoned in a sprawling, dog-eat-dog garbage dump and raped so frequently that she doesn’t even seem to notice anymore. A farcical string of bloodily violent incidents leads her to a life as the unofficially adopted daughter of a poetry editor who claims to have come from the same circumstances, and then eventually to a second life as the wife of a young district attorney, but in both cases violence and squalor cling to her like a stench, to use a frequently invoked metaphor.

This is the angriest I can ever recall Gilbert’s art looking. That’s saying something: My wife, for example, finds his books almost difficult to look at–“His characters just look so hard,” she says, and they’ve never been harder than here. Right from the get-go his figures seem dashed off as in a white heat, while several early landscapes and backgrounds in the hellish dump look like the whole world is on fire. His almost supernaturally confident pacing of scenes and the cuts between them evoke in their matter-of-factness the acceptance of everyday brutality by the characters themselves. At times the jumpcuts can be quite funny, as when a scene between Empress and her adopted father consists solely of a pair of panels where they argue over whether a glass is half empty or half full; both Hernandez and his characters know how reductive this exchange is, yet also know it’s quite true to who they are.

But when that metronomic editing slows down, the effect is powerful, particularly because it is often done to draw out scenes of gutwrenching violence or tragedy. (The centerpiece scene in the brothel is as disturbing as the death squad attack in Gilbert’s masterpiece Poison River; there as here a knowing glance is all-important, but here it causes murder rather than prevents it.) The end of the book changes the pacing again, revving up the jumpcuts to suggest unsolved crime and unglued minds, and to be honest I’ve revisited it three or four times today and I’m still not sure what’s going on. Maybe that’s a problem, maybe it’s not. Since I see myself revisiting this book, a gruesome, enraged commentary on just how shitty things can be, many, many times in the future, I’m leaning toward “not a problem at all.”

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: New Tales of Old Palomar #1-3

November 26, 2010New Tales of Old Palomar #1-3

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Coconino/Fantagraphics, 2006-2007

32 pages each

$7.95 each

Buy them from Fantagraphics

Buy them from Amazon.com

By the end of his post-Palomar Love and Rockets comics, Gilbert often draws his characters like they’re the only people on earth. Their acts are isolated against a blank background, or they parade themselves in front of us and address us directly like B-movie actresses at a convention panel or motivational speakers on an arena stage. They’re larger than life and spotlit as such.

New Tales of Old Palomar reminds us that life goes on around them, and the earth surrounds them. Beto’s contribution to the Igort-edited Ignatz line of international art-comic series, these three issues present a suite of stories from Palomar’s past. They fill in a few notable lacuane–where Tonantzin and Diana came from, what was up with the gang of kids we’d occasionally see who were a few years older than the Pipo/Heraclio group, how Chelo lost her eye. A lot of this turns out to be really fascinating, especially if you’ve spent a month immersing yourself in the Palomar-verse. But to me it’s not what’s told that matters, but how it’s told. Maybe it’s seeing Gilbert work at magazine size again, maybe it’s the creamy off-white paper stock, maybe it’s the thinner, finer line he’s using, but New Tales simply feels different than anything we’ve seen from Beto in years.

Once again characters are rooted in the streets of Palomar and the wilderness beyond, stretching off in all directions. Indeed the wilderness, as much as I hate to use this cliché, is as much a character in these stories as anyone or anything else: It’s vast, almost abstractly so at times, and it houses at least as many mysteries as Fritz’s backstory. Gilbert uses it to bring the strip’s mostly forgotten supernatural and science fiction elements back to the foreground–ghosts and spirits on one hand, and sinister “researchers” on the other. And these in turn tie in to long-abandoned plot threads: Tonantzin’s slow-burning madness, say, or the hinted-at Cold War experiments that seem to have quietly unleashed genuine danger in Palomar’s surroundings, or the way Palomar seems to exist as a spiritual entity quite aside from the people who happen to inhabit it. But these connections are mostly teased out, not hit with the sledgehammer emotional force of the post-Palomar comics’ equivalent sinister or macabre bits. The trick Gilbert pulls here is to persuade us, through visuals and pacing, to put aside our foreknowledge of all that comes later, all the tragedy and horror, all the manic escapades and blackness, and exchange it for a quiet, yellowed air of mystery and menace–and eventual safety, since all’s well that ends well here. The shadow is there, but it’s only that, a shadow of the crystalline moment at hand, hinting at a vast and unknowable world beyond. Beautiful stuff.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

November 24, 2010 Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

featuring “Venus and You″

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

56 pages

$4.50

Out of print at Fantagraphics

Buy it as featured in the Luba hardcover from Fantagraphics

Buy it as featured in the Luba hardcover from Amazon.com

(Programming note: As I did with Jaime, I’ll be reviewing Gilbert’s contributions to the final issue of Love and Rockets Vol. 2 and (when I get to them — still a ways to go!) the first three issues of Love and Rockets Vol. 3 on their own. Click here read about the Jaime half of this comic.)

In order to read this story, I had to turn to my massive Luba hardcover, which I believe collects all of the post-Palomar Palomar-verse stories in chronological order. I sorta wish I’d realized this going into my read-through of all Gilbert’s work, since it’s obviously how I prefer to read this stuff. But for the purposes of a review-a-thon like this it wouldn’t have made much sense to consume this material in one giant hardcover. I wouldn’t have been able to do the whole gigantic work justice in one go, especially compared to the more manageable chunks in which I read the rest of Los Bros’ work; besides, no way could I have maintained my schedule by reading the thing in two days.

But flipping through the book to get to the final post-Palomar story (to date, I believe), which remains otherwise uncollected, I discovered that the stories immediately leading up to this one are “Blackouting” and “Doralis.” If those titles don’t mean anything to you I won’t spoil it, but they were the two big audible-gasp, dropped-jaw, cover-gaping-mouth-with-hand moments from High Soft Lisp and Luba in America. “Devastating” just about covers it, though not quite–they’re the big black holes into which their respective storylines drop. Where could Beto possibly go from there?

The answer is “a happy ending,” of course. At long last he returns to Venus, Petra’s daughter and one of the least damaged, most well-adjusted, most self-assured characters in the whole post-Palomar oeuvre. Now a teenager, she’s virtually everything her mother and aunts never got to be. She has a healthy, fun-sounding sex life with her boyfriend, who also happens to be her best friend of many years’ standing. She gets along great with her mother and both her aunts despite their estrangement. Her personal segment of the extended family seems quite secure — Petra has remarried to a guy who sounds swell, Petra herself put on a bunch of marriage-security weight and sounds happy herself, Venus and her kid sister get along. Venus is smart, funny, quick-witted, kind-hearted, a pretty unabashed nerd, beautiful…just a real kick-ass kid. It’s an uplifting note to end on after all this darkness.

Most uplifting at all is Venus’s power to process and contextualize her family’s story healthily. In her interactions with her mother and aunts, we see she’s able to admire their admirable qualities — and for all the horror we’ve been shown, all three sisters have plenty to admire about them, their simple survival not being the least of it — while not letting their bad sides taint her. (If that takes a bit of denial on her part, so be it.) For example, she’s revealed in this final strip to be her Tia Fritz’s number-one fan. She’s seen all of her aunt’s movies–with the possible exception of the surreal faux-porn flick from her pre-movie-star days that’s currently causing a lot of buzz. Venus dismisses it as basically unimportant compared to Fritz’s latest release, which Fritz herself wrote and directed. We the reader can see the symbolic resonance of the clip from the strange pseudo-porn movie — a man emerges from a mist-enshrouded forest to have sex with a nude Fritz, her breasts swollen by pregnancy, only to transform into some sort of beast in the middle of the act, then disappear into the background, leaving Fritz naked, disoriented, and alone. It’s her life as a sexual being, basically…and Venus doesn’t give a fuck, because she prefers the movie where Fritz is the writer-director-star. I get the feeling that Venus is equipped to be a multi-hyphenate for her own life in a way that few of the characters we’ve met have been.

Indeed, in our final glimpse of her, she asks her late family and friends — Grandma Maria, Gato, Sergio, Dolaris — to watch over the three sisters, and then provides these guardian angels’ answers to her prayers herself, same font, same caption style. Writer, director, star. I wish her all the luck in the world.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: High Soft Lisp

November 22, 2010 High Soft Lisp

High Soft Lisp

(Love and Rockets, Book 25)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, January 2010

144 pages

$16.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

I’ve never seen a cartoonist so thoroughly dismantle–discredit–his own artistic preoccupations.

In High Soft Lisp, Gilbert traces the relationship history of Fritz Martinez, the ultimate sex goddess in a career full of them, and in so doing reveals that her every fetish outfit and sexual free-for-all is fruit from the poisoned tree. Lots of characters in this book enjoy the living shit out of Fritz’s sexuality, not least Fritz herself, but to a man and woman they’re revealed to be creepily predatory about it, embracing the worst in themselves and encouraging the worst in Fritz. And here’s the thing: What have we been doing over the hundreds of pages we’ve spent watching Fritz adorably and kinkily fuck her way through the post-Palomar cast of Beto’s comics? What has Beto been doing? What does that say about all of us?

That’s one way of looking at High Soft Lisp. Another way is to expand Beto’s list of targets to include his critics. “Ooh ooh, the criticth are going to dithapprove becauthe I’m naked again!” Fritz says at one point after drunkenly stripping after an apocalyptically awful confrontation with her lifelong misery’s author. “I’m too often naked in my filmth. Criticth write with the finger of God!” “Fuck them,” her girlfriend Pipo responds, and it’s clear this is as much an internal authorial conversation as it is one between two characters. But then! Pipo…ugh, just ugh. Just another victimizer, no matter how complicit Fritz is in her own victimization. Shouldn’t someone be expected to know better? Dammit, where is Gorgo when you need him? And then you realize Beto wonders if maybe the critics have a point.

Certain story developments in this book made me return to Human Diastrophism and Beyond Palomar to review certain characters’ backstories, and in so doing I discovered just how different Gilbert’s art has become–much less dense, much less rooted in three-dimensional space, much more prone to techniques akin to those he uses in his non-narrative work. At this point characters routinely break the fourth wall against vast white spaces, or do their dirty deeds isolated against a blank background as though they’re the only objects on earth. And yet it’s still a single, well-observed bit of portraiture that impressed and crushed me the most here: the shaky half-smile half-grimace of pain on Fritz’s face as her father tells her off once and for all. It’s the most intensely human moment in the whole book, at the moment when Fritz’s humanity receives perhaps the most vicious wound it possibly could. I care about this human being, still a human being underneath all the sex bomb trappings, even as author and audience and characters conspire to keep that trap shut.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Luba: Three Daughters

November 19, 2010 Luba: Three Daughters

Luba: Three Daughters

(Love and Rockets, Book 23)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2006

144 pages

$16.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

Gilbert tips his hand with the title. Not three sisters, even though that’s the relationship by which Luba, Petra, and Fritz can be defined without referencing anyone else, and even though that’s what they call each other all the time (well, that or “thithter,” depending). No, they have something — someone — else in common. She’s present in the very first panel of the very first story, in which she’s posited as the source of Luba’s misery. She’s present in the pivotal, never-shown blowout that sunders the three daughters’ relationship. And she’s present in the sudden, shocking, utterly depressing turn of events that happens in the book’s final story as well — a lethal legacy hinted at here and there throughout the book (a strip called “Genetically Predisposed,” Guadalupe’s fond memories of the way her daughter’s dad Hector would insist upon their medical monitoring) but which finally blossoms as vibrant, larger than life character is reduced to skin and bones and eventually nothing. If this were another series altogether I would describe this everywhere-and-nowhere character as “the hole in things, the piece that can never fit, there since the beginning.” Instead, we have another description: “I stayed to find the…the person inside that glorious frame, that…and of course the more I searched, the closer I got…?”

The inescapable ripples of long-ago events over which the characters we love had no control, and the ripples their own shitty actions send out, ensnaring others: That’s what hit me so hard about Three Daughters. Luba, Fritz, and Petra can have all the wacky sex adventures they can stand — they’re still paying for someone else’s sins in a way that can just clear the decks of their lives at a moment’s notice. Hundreds of pages of material about their zany complex romantic misadventures together brought to an end by an argument we never even see, a character we’ve known for literally decades healthy on one page, revealed to be deathly ill with stunning portraiture on the next page, gone the page after that. People two generations removed are still riding the Gorgo Wheel.

In The Book of Ofelia there was a knockout line about how God makes our lives so miserable so much of the time so that we won’t feel too bad about dying. As I’ve read Gilbert’s Palomar-verse material I’ve come to think this is basically the case. Once I talked about how unlike Jaime’s stage-like intra-panel layouts, Gilbert’s characters were placed unassumingly against backgrounds that went off in all directions. But by this point they’re stagey almost to an abstract degree, sometimes fourth-wall-breakingly so. It’s in these strips you can see the hand of these characters’ creators more than any others. The background, more often than not, is blank. It’s them and the void.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Luba: The Book of Ofelia

November 17, 2010 Luba: The Book of Ofelia

Luba: The Book of Ofelia

(Love and Rockets, Book 21)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2005

256 pages

$22.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

It makes my job as a critic a lot harder when I’ve spent nearly an entire book composing its review in my head only for the final few pages to smash it to smithereens. In that sense, reviewing Luba: The Book of Ofelia is hard work.

Like, I really thought I’d figured out what Gilbert was after in his post-Palomar Palomar-verse work, you know? Take the story out of a small living-in-the-past Latin-American village and transport it to shiny, wealthy California; whittle the cast down from a whole town full of people to a group that’s still large but is essentially two families, Luba’s and Pipo’s; remove the Cold War/yanqui-go-home politics and replace it with a still biting but lower-stakes critique of capitalism and showbiz; tone down the magic realism to the kind of stuff you can explain with “that’s the kind of thing that happens in comics”; crank up the sex scenes. The end result? The funnybook-Marquez days are over, and now Beto’s free to do the crazily complicated soap-opera sex-farce sitcom of his demented dreams.

And not in a dumbed-down way, either! Beto chronicles one of the book’s most titillating storylines, Pipo’s crush-turned-affair with Fritz, with genuine insight. I actually recognize the singleminded way Pipo pursues Fritz despite neither of them having ever identified as lesbians, the way the idea got into her head and heart and crotch and simply grew and grew, never taking no for an answer. I also recognize the way the intensity of their feelings sort of seeps into increasingly intense sexual experiences with all sorts of other people, too.

The comedy’s never been sharper or funnier than it is here, either, nor as tied to Beto’s great strength, the depiction of the human form. Cases in point: Boots and Fortunato. (Excuse me–FORTUNATO..!) Boots’s teardrop-shaped body and architectural hairdo framing her preposterously perpetual scowl and giant Muppet mouth as she stares directly at the reader like Chester Gould’s Influence and screams “MY APPEAL IS INFINITE!” while having an orgasm? Classic shit, man. And FORTUNATO..!? Basically the Sergio sketch in comic form and minus the Lost Boys reference. His taciturn expression and the fact that he’s actually considerably less attractive then most of the other young men in the book only made it funnier. The last time we see his powers in action he’s actually got Kirby Krackle surrounding him for god’s sake. For all that creepy and sinister and violent stuff would bubble up from time to time–from the anti-Catholic rioting in Europe to Petra’s serial assaults on anyone she feels is a threat to the people she cares about to the god-knows-what that was going on with Khamo’s drug contacts–I got within the final ten or so pages of the book thinking that my two big takeaways were going to be these two characters cracking me up.

Then the last few pages happened, and wham, I’m just punched in the face with the fact that we’re not on Birdland‘s higher plane, we’re in Poison River‘s fallen world. In this world some people will stop at nothing to get what they think they want–money, sex, love, payback. In this world there’s a price to be paid for all the hijinx and sexual slapstick, one that no one involved really deserves to pay but one that gets paid nonetheless. It’s easy to forget given how happily extreme so many characters’ behavior has been, but in this world you can push people too far. I thought I had a handle on The Book of Ofelia, but of course it turns out there was no such thing all along.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Luba in America

November 15, 2010 Luba in America

Luba in America

(Love and Rockets, Book 19)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2001

176 pages

$19.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

A series of observations on the first volume of the Luba trilogy:

* I’m amused by how quickly and matter-of-factly Gilbert will establish a vital new aspect of the story, usually through the mouths of babes. Oh yeah, Khamo had a history as a drug-runner, did we not mention that? I almost forgot, all of Luba’s kids except Guadalupe are gay–just fyi!

* Which reminds me: Many of the stories in this volume are told either from the perspective of Venus, Petra’s precocious, quick-witted but kind-hearted ten-year-old daughter, or with her as a focalizing character even if we’re seeing things she isn’t. It’s a bit of a throwback cousin* to “Toco,” that very early more or less contemporaneously written* story about Jesus’s consumptive, long-sleeved little brother who ended up dying young, in which he’s waylaid from a beach excursion by a child molester, to whose ministrations and lethal fate Toco appears completely oblivious. Similarly, things like the identity of her mother’s paramour and her “normal” Tia Luba’s long and sordid history go right over Venus’s head. But at the same time she’s far more perceptive than a lot of the other characters: She sees who stole the family’s good-luck totem (courtesy of a visual device I had to revisit to figure out but which since became one of my favorite parts of the book), she knows her mom and her Tia Fritz sleep while the two of them have no clue, she senses that Luba’s prolonged absence means something’s really wrong there, and so on. The point is that this childlike blend of insight and innocence is almost exactly like a reader’s perception of the Palomar-verse itself: the thrill of piecing together things we’re not “supposed” to know about the characters, coupled with the somewhat disconcerting and disorienting knowledge that there’s a lot of stuff going on under our noses, behind our backs, and over our heads.

* Speaking of kids, there’s something blackly comic being communicated about parenthood in this volume–way less harsh than the horrifying glimpses of Maria and Luba’s parenting skills we’ve seen before, but on a continuum with them at least. Basically, mothers and fathers are just kids who happen to be old enough to have had kids themselves. Right?

* I find myself oddly disturbed by just how persistent the threat to Maria and Luba’s extended family and circle of friends apparently is. No matter how much time passes, no matter where they go, no matter how far their circus-like lives take them from the tone of that Poison River/”Gorgo Wheel” material, you just never know when taciturn men with guns are going to show up ready to kidnap or kill. Seeing the picture of Garza on his daughter’s office wall as Luba tried to bury the hatchet was like seeing something from a nightmare suddenly appear in your real life. Ugh–chilling.

* This just occurred to me, and there’s no way to say it without sounding crass so I’m just gonna bite the bullet and here goes: This volume contains maybe the single funniest sight gag in the Palomar-verse’s history as well as what I found to be the sexiest sequence, and both involve bodily fluids going into or out of Petra’s mouth. I’m just sayin’!

* This is the kind of book where in the middle of a conversation, the characters can flash forward what looks to be twenty-five years into the future while continuing that same conversation, and I don’t even blink.

* Khamo is the best-looking guy I’ve ever seen in a comic. I am drearily heterosexual, but even still there’s the occasional man who just makes me want to sit and stare and appreciate his beauty–The Man Who Fell to Earth/Thin White Duke-era David Bowie and Ian Somerhalder, for example–and Khamo in his prime is, I think, the first comic-book character ever to do this. Dude is stunning.

* Last night I actually dreamed I was at the record store/comic shop Venus and Petra frequent (albeit for very different reasons). I’m pretty sure I was there with Venus. I discovered that they had an incredible toy selection as well, and was playing with a Mego Hulk dressed as a hillbilly.

* About halfway through the book last night I took a bathroom break, and as I stood there peeing and thinking about the comic and its characters, I mentally asked myself, half in exasperation and half in utter fascination–“Who the hell are these crazy people?” Find me another comic where you can ask that–where the cartoonist has struck this precise balance of creating characters who are totally plausible and also totally ridiculous, riddled with mysterious voids and yet so well-defined that you just know you can fill in the blanks if you try hard enough–and I’ll eat my hat.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Fear of Comics

November 12, 2010 Fear of Comics

Fear of Comics

(Love and Rockets, Book 17)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2000

112 pages

$12.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

The one moment in Fear of Comics, a collection of Gilbert’s short stories and experimental work from between the first and second runs of Love and Rockets proper, isn’t visual, but verbal. “Dr. Fritz, in this dream I look at you and I can only think of killing you,” says the bizarrely dressed character known as the Diva to her therapist. “I focus my hostility toward you because I’m actually angry with somebody else from my past who’s been abusive to me but it’s you I want dead. If I kill you all the world’s pain would go away because I would be satisfied…! God forgive me…”

“Not to worry,” Fritz replies in her trademark lisping voice. “It’th your dream and you’re thimply working out your reprethed daily fruthtrathionth.”

“My dream…?” the Diva replies.

In the next panel Fritz awakes with a shock, the crescent moon whose shape adorns the Diva’s headgear shining coldly through her dark bedroom window.

It is just such a chilling moment, that one little turn of phrase where suddenly Fritz’s dream avatar realizes that dream though this may be, she’s in mortal danger. Shudder-inducingly subtle. And frankly I think subtlety is an underrated quality of Beto’s comics. Especially in a collection like this one, where the selling point is that it’s all the weird, wild, surreal, sexy, and violent shit he did when he really cut loose between Palomar-verse runs, it’s important to note how many of the strongest moments are also the quietest ones. Take his little parable of skill, jealousy, and ignorance “The Fabulous Ones,” for example. Not to undersell the prodigious penises of the nude characters or the grotesque act of brain-eating that forms the crux of the story, but the really haunting bit is watching the surviving tribesman sitting there after placing his slain friend’s brain in their slain rival’s skull, in hopes that this will revive the man so that they can apologize for having killed him in the first place. The act isn’t the really troubling part, it’s his silent realization that he’s made yet another terrible mistake, and the subsequent silent panel of him fleeing, knowing he can never really run away from his crime. Or look at “Father’s Day,” a bleak, loosely inked little thing about a well-meaning father who pays for his meddling in his wayward teen daughter’s life with his own: It’s not dad getting beaten that gets you, it’s his daughter sleeping, unaware of his fate, and his wife waiting up, dreading it. Or look at what I believe is the collection’s best known strip, six panels of a man who looks like a caricature of Richard Nixon convulsing or cramping up against a generic trees-and-cityscape background under the title “Heroin”: I’ve said this before, but while I may not know what this strip is about, I know what it’s about. Or take perhaps my favorite recurring device in Beto’s oeuvre: The mystical tree that will grant supplicants their wish as long as they can bear to look at its true face. We never see that face ourselves, and what we do see tells us little other than that whatever it is is incomprehensible: A shapeless shadow, the edge of a giant clockwork gear.

Fear of Comics is a wonderful book, one of the finest short-story collections the medium has ever produced. It’s laugh-out-loud funny at times, filthy at others, disgusting and poetic and black as midnight at still others. And it’s a showcase for comics’ premier naturalist to abandon that style altogether, to take his distinctive and exaggerated figurework to their absolute extremes, to tell stories that feel like neither the magic realism nor the science fiction for which he is best known but rather like fairy tales, or even myths of some creepy nihilistic religion. It’s definitely weird and wild. But for my money, it’s loudest when it’s quiet.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Amor y Cohetes

November 10, 2010Amor y Cohetes

(Love and Rockets Library: Short Stories)

Gilbert Hernandez, Jaime Hernandez, Mario Hernandez, writers/artists

Fantagraphics, 2008

280 pages

$16.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

One of the things I’ve missed out on in reading through Love and Rockets one Bro at a time is seeing where they stood in relation to each other. I’m told by at least one trusted reader who was there at the time that “it’s the way they played off each other!” is an overrated element to the original serial-anthology format, but that’s fine, because my interest in this topic was more historical than critical. Isn’t it fascinating to know, for example, that “The Death of Speedy Ortiz” was in the same issues as “Poison River”? And I’ve heard straight from the Bros’ mouths that seeing what the other one was doing in the early issues helped shape the storylines that would define each of them: Gilbert was so impressed by Jaime’s obvious mastery of the “cute girls hanging out in a science-fiction setting” set-up in his Locas strips that he abandoned his similar material to create Palomar; then Jaime was so impressed with the extensive, realistic character work Gilbert was doing in Palomar that he beefed up that aspect of the Locas stories. It wasn’t so much “I’ll see you and raise” (although surely that’s a part of it, as it is whenever any talented people work in proximity) as it was each brother seeing what areas in their shared ideaspace gave them the room to bust loose.

In collecting all the (mostly) non-Locas, non-Palomar odds’n’ends from the initial run of Love and Rockets from both Gilbert and Jaime–and Mario too, the “sometimes Y” to Beto and Xaime’s AEIOU–Amor y Cohetes reinforces that conception of the brothers’ working relationship. It’s not one-upsmanship, it’s not trading eights, it’s more a matter of pulling from a collective pool of ideas about comics. For example, it’s striking how similar the two brothers’ science-fiction work looks. In “BEM,” the SF adventure that I believe was Beto’s very first L&R material, he hatches and spots blacks and draws romance-comic female faces in the way you expect from Jaime’s genre work. I mean, it’s still recognizably Gilbert, but it’s quite clear that both brothers conceived of these kinds of stories as ones that are by default painted with the same visual palette. As time passes, Gilbert’s sci-fi stuff dwindles down to the single storyline of Errata Stigmata, the asymmetrically coiffed character whose omnipresence in L&R promo material over the years always left me wondering who the hell she was since I’d seen neither hide nor hair of her in Palomar or Locas; even then, his layouts are wide open, using far fewer panels per page, and are driven by vast fields of stylishly designed black–Jaime-esque, in other words. Meanwhile, a pair of punk-based Beto stories–one the fictional history of a shoulda-woulda-coulda been the next big thing bad as told by one of their fans, the other an autobio vignette about the night his 17-year-old future wife puked her way through his would-be panty-dropping tour of punk hotspots–show the same easy familiarity and casual mastery of that milieu that Jaime’s does. How’d he do it without all the practice Jaime had? My conclusion is that, like how sci-fi should look a certain way, knowing how to write punk comics is just part of their shared gestalt. Hell, Beto even contributes an awesome little wrestling story, about the real-life night he saw (pre-Adorable) Adrian Adonis basically go nuts, that further proves the point.

The road goes both ways, of course. Jaime’s light-hearted sci-fi-comedy romps with pretty teenager Rocky Rhodes and her absolutely adorable robot sidekick Fumble eventually veer off into the sort of sad, you-can-never-go-back cul de sac of regret that’s normally Beto’s territory. There’s also a barely-veiled autobio story about the day a KKK event in his neighborhood provoked a riot that feels more Love and Rockets X than Locas. When the Bros swap characters for a special issue, Jaime hews much closer to the spirit of Palomar in his Luba/Maricela/Riri story than Beto does in his proto-Birdland gender-bending sci-fi sex romp with the Locas (whom he eventually transmogrifies into Locos!). To put even more of a point on it, Jaime takes a zany old Looney Tunes-style comic Beto did as a kid and redraws it with Maggie and Hopey in the lead roles, and damn if it doesn’t feel like the kind of kinetic, wordless romps Beto throws in as short stories from time to time as an adult.

Thrown into this mix for the first time in the L&R books I’ve read is Mario. Dude’s an accomplished cartoonist too, and in a style that I think anticipated a lot more comics I’ve seen than Jaime’s or Gilbert’s, believe it or not–his blobby, dynamically dashed-down inks feel alt-Euro to me, poised halfway between expressionism and naturalism. His main storyline, about the fallout from a coup d’état in a slightly sci-fi-tinged Latin American country, unfolded over the course of short stories spaced out over years, and offers more proof that the Bros were all building off the same foundation–it’s quite easy to place his “Somewhere in California”/”Somewhere in the Tropics” political thriller somewhere between Maggie and Rena’s Mechanix-era revolutionary misadventures and Gilbert’s serious-as-a-heart-attack Cold War/Drug War shocker Poison River. Which makes sense, I suppose, given that he and Beto collaborated on several of the strips.

Ultimately it’s Gilbert who emerges as the star of Amor y Cohetes. While Mario’s stuff feels like a cameo and Jaime’s like a detour, Gilbert’s non-Palomar work comes across like a second main throughline for his career. Whether incorporating Frida Kahlo’s style and a dizzying array of cultural and political eyeball kicks into his biographical strip about her, placing autobiographical stories and dialogue in the caption boxes and word balloons of totally incongruous superhero and sci-fi artwork, crafting harsh and mostly wordless short stories about violence, or developing Errata Stigmata into a damage case every bit the equal of a Palomar resident, he comes across as restless and relentless in his desire to do whatever he can think of doing with comics. All three Bros shine on this shared stage, but Beto’s the one pushing through the audience and taking it out to the street. It’s exciting to watch that shared ideaspace expand.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Birdland

November 8, 2010 Birdland

Birdland

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Eros, 1994

104 pages

$14.95

Sold out at Fantagraphics

Buy it used from Amazon.com

“It occurred to me: The basis of fiction is that people have some sort of connection with each other. But they don’t.” –Richard Harrow, Boardwalk Empire

Does Gilbert Hernandez agree with this, or doesn’t he? That seems to me to be the central question of the Palomar books, and the answer depends on which one you’re reading. Palomar is very much a fiction of community; its stories are not simply about a collection of individuals who either interact or don’t, it’s about that web of interaction and the collective effect it has on everyone involved in it. Certainly in the earlier, lighter material it appears that the importance of this connectivity is paramount for Beto — a sentiment that recurs anytime the characters chafe at the encroachment of the outside world, or at co-option by the United States. On the other hand, you have things like Tonantzin’s self-destruction, or the pack of murdering ghouls who make up the cast of Poison River. In cases like these, all the things we think of as potential connections — love, sex, family, political and ideological worldviews dedicated to the greater good — are revealed as enormously destructive, utterly indifferent forces, at least as well equipped to tear people apart as bring them together. One could easily conceive of Palomar as a long chase scene in which destruction is constantly nipping at connection’s heels.

Birdland, then, is connection opening up the healthiest lead it’s had in hundreds of pages. Doing a straight-up porn comic that borrows the Palomar-verse characters Fritz and Petra gives Beto the freedom to be as silly and utopian as he wants, something he couldn’t get away with in the naturalist, politically aware world of Palomar and Love and Rockets proper. As a result, he can spend three-quarters of the story watching various adulterous pairings unfold as the characters attempt to compensate for their unhappy unrequited loves and unfulfilled lives — and then blammo, aliens can abduct everyone and grant them the gift of totally guilt-free fucking, in which they inflict no emotional pain on one another whatsoever and everyone can get exactly what they want — and then double-blammo, a cosmic mishap shows them how their romantic misadventures, their pleasures and sorrows, echo those of basically every life form throughout the history of life itself. Talk about a happy ending!

Perhaps the easiest way to see what he’s up to here is to note that by the project’s very nature, the human bodies with which he has always shown such proficiency must needs connect. I mean, just look at the amount of luscious, loving detail Beto puts into, say, Mark’s body hair, or Inez’s vagina. When a guy who draws like that is gonna do a sex comic, you’re gonna feel like those connections are worthwhile almost by default. That’s what happens when bodies start slappin’.