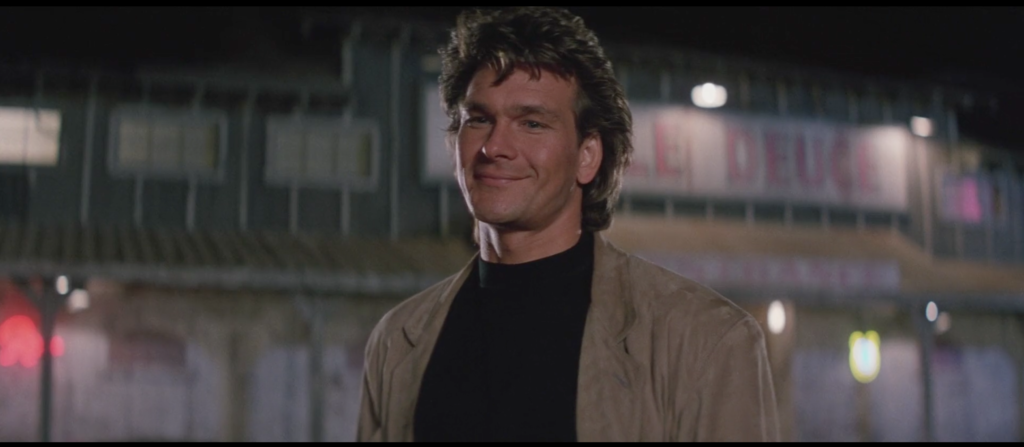

DALTON: Dalton.

RED WEBSTER: Red Webster. How long you gonna be in town?

DALTON: Not very long.

RED WEBSTER: That’s what I said 25 years ago.

DALTON: Really? What happened?

RED WEBSTER: Oh, I got married. To an ugly woman. Don’t ever do that, it just takes the energy right outta ya! She left me though. Found somebody even uglier than she was. That’s life. Who can explain it.

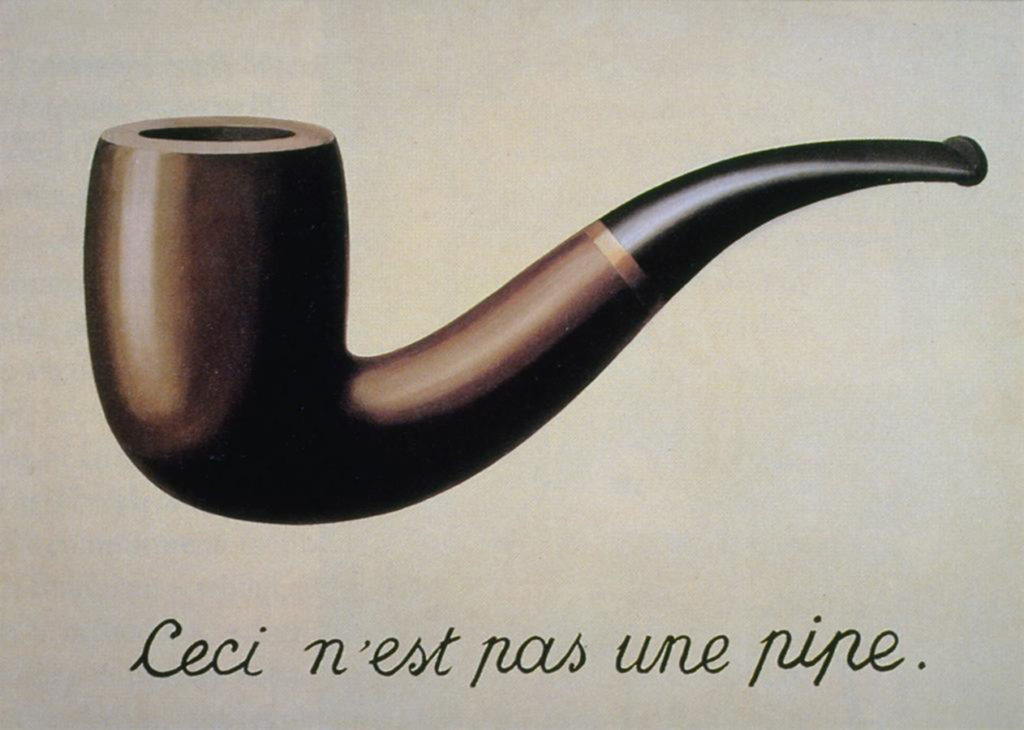

This is a segment of the first conversation Dalton has with Red Webster, auto parts supplier and owner of the closest business establishment to the Double Deuce. When this exchange takes place, these men have known each other for exactly thirty seconds. Their only dialogue up to that point is about which parts of Dalton’s vandalized car need replacing, and whether he should put in a standing order due to the nature of his job or pay as he goes. Compare this interaction to the way Dalton speaks to the staff of the Double Deuce the night he arrives—spartan and only barely polysyllabic. Red, it seems safe to say, is an oversharer.

When Red starts the story of his failed marriage to his ugly wife, however, it’s not clear this is anything more than a take my wife please joke, “It just takes the energy right outta ya” being the punchline. But then he keeps going, in short little bursts that sound like Manic Street Preacher song titles from the Richey Edwards era:

she left me though

foundsomebodyevenuglierthanshewas

that’s life

whocanexplainit

And boy oh boy does it sound like he wants to keep going from there! Credit the naturalistic performance of actor Red West (yep), a former high school chum and entourage member of Elvis Presley’s; it sounds like he’s actually cleaning out his mental closet right in front of us.

Unfortunately the vicissitudes of capitalism demand that Red pause long enough to ring Dalton up. This gives the cooler a chance to reinsert himself into the conversation before Red can continue his bittersweet reminiscence. Seconds later Brad Wesley and his chief goon Jimmy pop in and the moment is gone. Yet I often think of what it might have been like had they never arrived, or had Dalton never piped up. How far down the Red Webster hole could we have fallen?

Oh, I got married. To an ugly woman. Don’t ever do that, it just takes the energy right outta ya! She left me though. Found somebody even uglier than she was. That’s life. Who can explain it. Went to a seminar once. Thought it’d sort me out. Est, they called it. Bee Ess, you ask me. Cost a pretty penny though. Had to sell the old place. Moved in with my stepdad. Hell of a man. Saved my mother from herself, I reckon. Daddy died at Anzio. Stepdad came into the picture a year later, think it was. Car salesman. Figure that’s where I got it from. Bum leg. Died in ’77. Boat accident. Hell of a thing. Seen that boat store cross the street? They’re the ones sold it to ‘im. Nearly went outta business. All that bad press. Settlement put my niece through med school. Brother never forgave me for it. Wanted her to go into the family business. Took over Momma’s apiary after the the cancer took her. Loved his little girl. Figured she’d follow in his footsteps. She had different ideas. People hate different ideas alright. Always do. Crazy ol’ world. Wound up sellin’ the bees anyways. ‘Llergic. Twenty-two years and not a sting. Tripped on a garden hose. Face first, right into the hive stack. Coma. Thought he’d lose the eye. Gotta wear one a’ them patches now. Looks like a pirate. Who’d’a thought. Car salesman, last I heard. Full circle I guess. Shame, though. First-rate dancer. Thought he’d go Broadway. “Red?” he says. “The dance never made nobody’s bread taste better.” Had a point. Always called it that, the dance. Fancy-like. Heard they’re bringin’ that Batman back. From the tee-vee. Gonna be a movie. Darker, they’re sayin’. Thought I’d read me one a’ his funnybooks. See what’s goin’ on. The Batman, they’re callin’ him now. Don’t that beat all. Drove up to St. Louis. Found one a them stores, sells nothin’ but funnybooks. Die-rect Market, they called it. Die-rect to who? Reminds me of that Home Box Office. Gotta be pig ignorant to want a box office in your home. People linin’ up, yellin’ at you when the picture’s sold out. Kids sneakin’ in. Cold at night. Thick glass. Got some good progr’ms though. Boxin’. Seen that Die Hard on there. Helluva film. California. Never been. Don’t know what to make a them Kids in the Hall. You seen ’em? Pythonesque. Nature a’ the format, you ask me. Anxiety a’ influence. Nothin’ for it. Five’ll get you ten that’s why I sell car parts and not the whole thing. Wanted to do things my way. Outta my stepdad’s shadow. They fuck you up, your mom and dad. May not mean to, but they do. Larkin. Poet. English fella. Ain’t half bad. Spent nine months in Cornwall once, ‘fore I met the wife. Thought it’d be educational. Learn them Celtic dialects. Did some fishing. Hated it. Boats. They they are again. Recurrin’ characters, you might say. Who’s the author. There’s the question. Can’t find no answer. Never been what you’d call a religious man. Couldn’t see the percentage in it. Master a’ my own destiny’s how I like it. Funny way a’ sayin’ it’s all my fault. There it is. Still. You blame yourself, stands to reason you can fix it too. Better’n believin’ it’s all random. Agency, causality. Free wlll. Love’s a neurochemical reaction? Over-reaction, in my book. But who’s to say. Could be it’s inexhaustible. Could be one a’ them zero-sum jobs. Give love here, gotta take it away from there. Wife thought so. ‘Bout yanked my heart out, ‘fore I saw the light. Blinded by the ugly I suppose. ‘Less I used to see clear, and it’s heartbreak what done for my way a’ seein’ things. Ain’t that a kick in the ass. Wonder what else I got wrong. Shaped by circumstance. Sum a’ your experiences. Nature, nurture. Either or. Can’t step outside a’ yourself. Didn’t need a seminar to teach me that. Times are I look in the mirror, can’t even recognize m’self. Who’s that old man? Still got all my hair, though. Red as ever. Caught hell in school for it. Carrot top. Tried tellin’ em the name didn’t have nothin’ to do with it. La Rouge. Momma’s maiden name. French Canadian. Way back anyways. Looked into it once. Microfiche. Didn’t get very far. Fine print. Need glasses. It’s like I said: Used to see clear. Just can’t bring m’self to do it. Proud a’ these eyes, always have been. Girls loved ’em. Baby blues, they said. Got me further’n anything else I had goin’ for m’self back then. Still remember that first time. Told Momma I was goin’ to the pictures. She was a picture alright. To a fault. Hair trigger. Over ‘fore it started. Recovered fast though. Kept at it for two hours. Next day neither a’ us was walkin’ right. Mm mm. She was a one. State senator now. Mail her a donation every cycle. Sends a thank you. Neither of us says anything about it. Figure we don’t need to. Said all we needed to say that night. More’n one way to tell someone how you feel. You gotta tell ’em, though. One way or the other. No point to it all otherwise. Connection. Long and the short of it. That’ll be $2.99 for the aerial.