Posts Tagged ‘the bandstand’

360. Oscar, or the path not taken

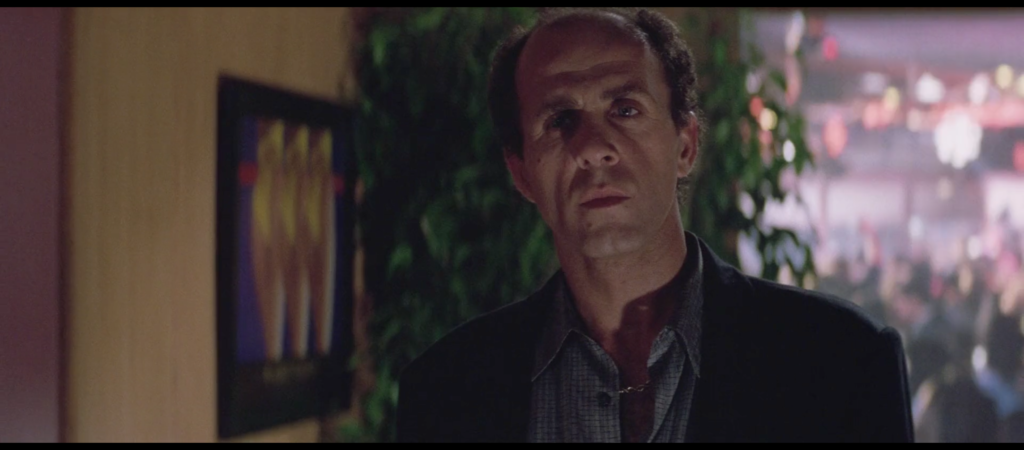

December 26, 2019This handsome devil right here is Oscar. He owns the Bandstand, the New York nightclub where Dalton’s working at the beginning of the film. As such he serves as two separate object lessons. First, he provides us with a solid point of comparison for just how creepy Frank Tilghman looks in this opening scene. Take a look at the man above, then at the man below, and consider what it takes to make the man above look like the more pleasant alternative.

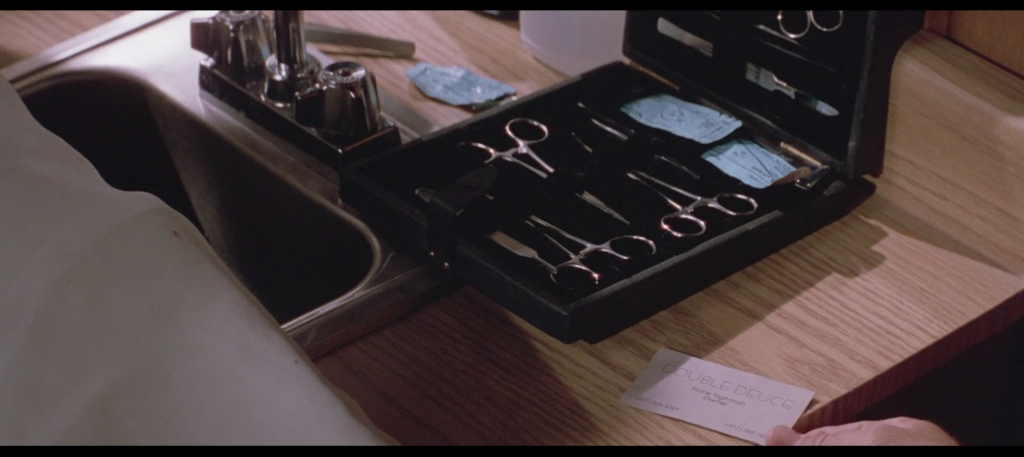

The second lesson pertains to something Dalton says moments before Oscar enters the room: “When the job’s done I walk.” He says this to Tilghman as a condition of taking the job at the Double Deuce; this is worth keeping in mind during the film’s final reel, as just up and walking away is not unheard of for Dalton and presumably for his mentor Wade Garrett too. The only issue is whether fixing up the Double Deuce but leaving Brad Wesley in control of Jasper constitutes the job being done. (I personally lean towards no, but then I’m not a cooler.)

Point is, you can look at the Bandstand—all that gold plastic, all those hundreds, no chickenwire around the stage—and deduce that, despite the fact that he was stabbed moments earlier, Dalton has finished the job. Certainly his bouncers are competent enough to help escort the knife nerd who cut Dalton outside and then just…prevent him from returning—an ideal bouncing maneuver according to Dalton’s Three Simple Rules. There’s nothing left for those men to learn from Dalton, ergo he can take Tilghman’s offer and split on the spot.

But there’s a world out there somewhere in the multiverse where Dalton continues to work at the Bandstand, fending off further attacks from the knife nerd. Perhaps he’s a low-level drug runner for one of the Five Families, and the mafia tries to move in on Oscar. Maybe Dalton winds up having to fight off various assassination attempts from hardened killers instead of Wesley’s goon squad. Maybe a horse’s head winds up in his bed. Dalton vs. the mafia is a movie I’d watch, and a prequel we deserve.

034. Thru the Eyes of Tilghman

February 3, 2019It goes ill with the Double Deuce. Frank Tilghman colorfully describes it to Dalton upon their first meeting as “the kind of place where they sweep up the eyeballs after closing,” and other than the lack of actual traumatic globe avulsions nothing we witness when we arrive contradicts this. It’s a hellhole. The bartender is a nepotism hire who robs the joint blind. The band gets pelted with bottles when they take five in order to urinate. The chief bouncer starts fights. Another bouncer fucks teenage girls in the supply closet. A waitress sells coke in the bathroom (presumably interfering with those customers who wish to snort coke in the bathroom, as is custom in classier establishments). Bottles, glassware, and furniture get smashed as regularly and thoroughly as the customers do. The owner is forced to waste precious man-hours bowdlerizing graffiti.

This much we know—now, anyway. But during the opening sequence, prior to our first visit to the Double Deuce, prior even to Tilghman’s description of the place to Dalton, we don’t know any of this unless we have watched the entire film before. That opening sequence, which depicts Frank Tilghman’s journey through the capacity crowd at the massively popular Bandstand where Dalton works at the time, is one of the reasons Road House rewards repeat viewings: Only people who’ve already witnessed the nightmare that is the pre-Dalton Double Deuce can understand what the hell Tilghman is doing.

In short order, Frank Tilghman marvels at…

- a handrail

- a bartender pouring shots

- a cash register ringing up a sale

- a waitress carrying a tray of drinks

- a man lighting a cigarette for an attractively dressed woman

- a credit-card transaction

- a man leaving a large cash tip

- a bar band

Remember, and this is key: Frank Tilghman owns a bar.

If you think I’m kidding about Tilghman “marveling at” these things, watch actor Kevin Tighe’s eyeline as he looks at each of these things in turn, whether within frame or via match cuts to the actions and objects in question. Then look at his face afterwards. He’s impressed. Thoroughly so. He takes it all in so intently that he reads like a villain casing the joint. Granted, he reads like that all the time, but as we’ve established, nothing that happens during the opening happens by accident.

You wanna know how bad things have gotten at the Double Deuce? Frank Tilghman, who owns a bar, looks at the basic components of literally any bar on earth like the apes look at the monolith in 2001. Forget the eyeballs on the floor. Just follow the eyeballs in Tilghman’s head.

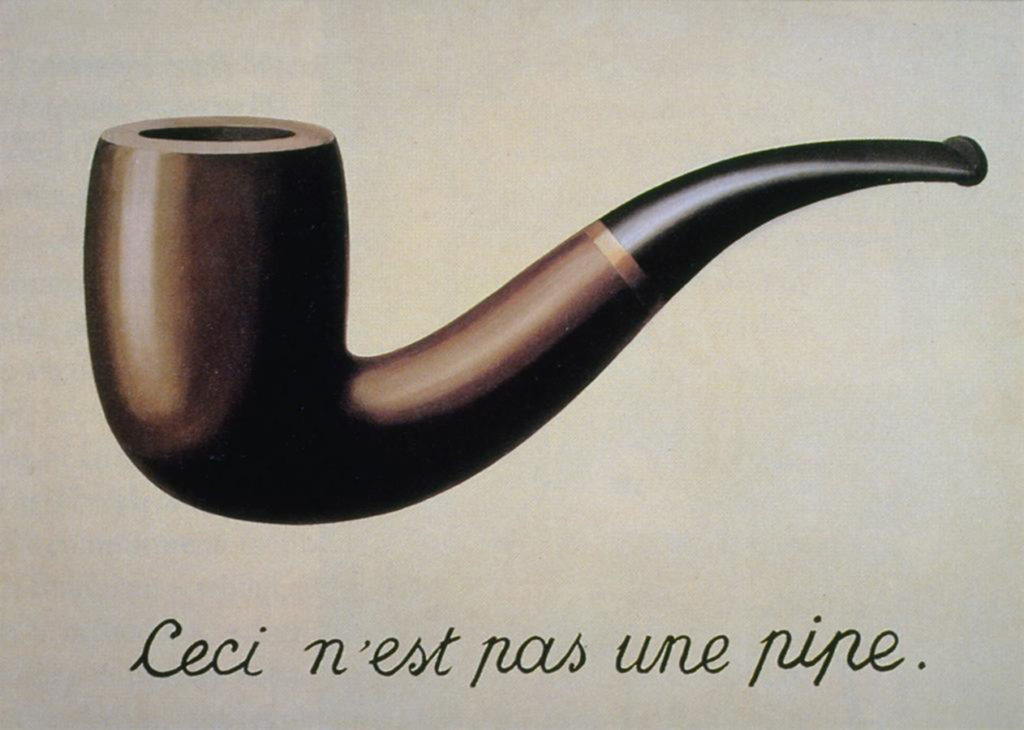

026. The Treachery of Images

January 26, 2019This is not a Road House. This is a woman’s ass. Other than a few moments that are so comically over-the-top they seem custom-built for people who use words like “bazongas” Road House does not really go in for random gratuitous objectification of women as a rule. In most instances where a man leers at a woman, that’s as sure a sign that bad shit is about to go down as the “DUNNNNNNN DUNN” string hit in John Williams’s score for Jaws. But this is where the title card devised by R/Greenberg Associates—the same company that designed the all-timer titles for Alien and Altered States—winds up.

This is normally the part where I come up with some deep-dive close-read no-prize explanation for the weird thing Road House just did. I’m hard pressed, however, to argue anything other than “they thought it would be fun to rile up the rubes by slapping the movie’s title across a woman’s butt.” I’ve seen this movie with enough people to know it usually succeeds in this aim. Not to mix the psycho-surrealist metaphor around which this post is constructed or anything, but sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

How then, to explain the following?

This is not Patrick Swayze. This is the same woman who will subsequently be labeled Road House. Her feet, anyway.

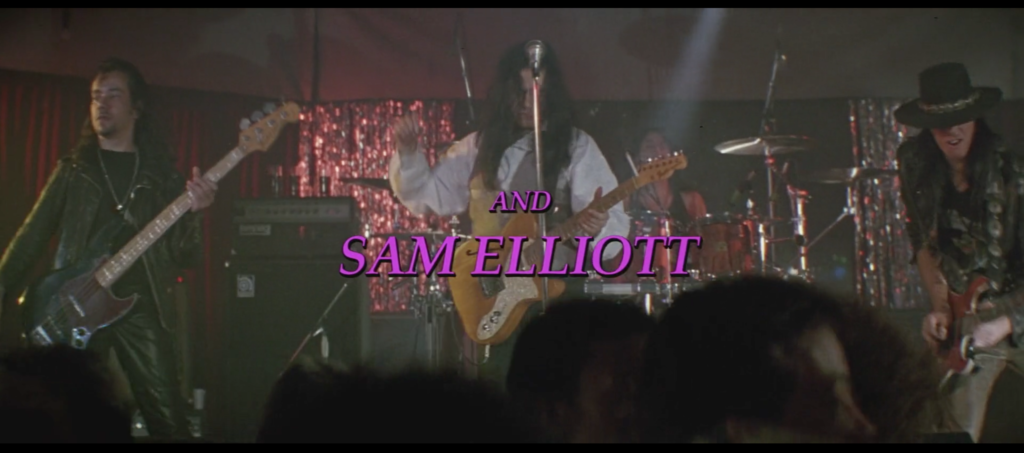

This is not Ben Gazzara. Not a single one of these guys is. This is Cruzados, the band that plays the opening song of the film. (Which is not the band that plays all of the other songs in the film.)

This is not Kelly Lynch. This is Kevin Tighe.

This is n—okay this is Kevin Tighe. CO-CO-CO-CO-COMBO BREAKER! Still, every rule needs an exception to prove it, as Dalton could no doubt tell us.

This is not Keith David. This is Kevin Tighe again. Moreover, Keith David is not an actor who has more than one line in this film.

This is not Kathleen Wilhoite. You know who it is.

While the three people here conceivably could be “Sunshine” Parker, Red West, and Julie Michaels—the names fit—they are not. They’re two extras and, wait, what was his name again?

This, as the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences could tell you this year, is not Sam Elliott. It’s Tito Larriva, lead singer of Cruzados. Interesting fella in his own right, but not a future Achiever.

While this could, and in fact should, be the Jeff Healey Band, it is not. It is still Cruzados.

The centered positioning of the credits, the lack of attention-demanding dialogue (it’s just the song and some bar chatter), the anomalous presence of one of the lead actors in the film who is himself usually centered in the frame: All of these factors make the viewer want to connect the name they’re reading to the person they’re seeing. No such luck.

Even the exception, Kevin Tighe, is less of one than he looks. When he appears, you are about to spend five minutes watching one of the most skin-crawlingly unctuous performances of the decade, and you will most likely spend much of your first viewing of the film believing him to be the villain of the piece. Naturally he’s the only actor billed in straightforward WYSIWYG fashion.

Again, I’ve seen this movie with enough people to know that in the right mindset these credits are disorienting, in a goofy, tipsy way. It makes people a bit rambunctious. “Wow, Kelly Lynch looks different!” “This is clearly not Sam Elliott.” That kind of thing. It’s like receiving an invitation to start talking back to the movie, written in purple Palatino. Stick that in your pipe and don’t smoke it.

012. Bandstand

January 12, 2019You’re sitting down to watch Road House is the first time. The action opens on a big glowing keyboard running down the side of the screen. The camera pans down and you hit a big neon red letter “R.” Awesome, Road House is about to begi—

Huh! “B.” Okay, not what I expected.

“BA.” BAR, it must be BAR.

“BAN.” Okay I give up.

The word is BANDSTAND, which is the name of the bar at which Dalton works at the beginning of the movie. Perhaps Road House will be the name of the bar where he works later on and oh no nevermind it’s the Double Deuce.

The first time I read A Game of Thrones I got confused by the very first proper name I saw: Ser Waymar Royce. This was before the show, and before I really knew anything about the books at all beyond “Tolkien but more hardcore,” so I had no way of knowing “Ser” was just a fantasy-universe way to spell “Sir.” I thought the guy’s name was Ser Waymar Royce, like Jan Michael Vincent or whatever. I can’t tell you how flummoxed I was by this. For some reason “Ser Waymar Royce” feels much more alien and strange than “Waymar Royce,” more alien and strange than I’d anticipated a series described as “The Sopranos with swords” was gonna get, and I had to shift my expectations pretty dramatically—only to shift them right back when I realized it was just a funny way to spell a familiar honorific.

The first time I saw Road House, this sign had a similar effect on me. In its first five seconds the movie went from comprehensible to incomprehensible, on a very small scale of course, but enough to have a disorienting effect that lingered long past the point at which the camera finished revealing the word “BANDSTAND” in radiant crimson. I can’t imagine this was the intent, but the opening shot prepared me for a movie in which anything could happen. In that respect, what followed did not disappoint.

011. First glimpse

January 11, 2019In the beginning was the Mullet, and the Mullet was with Dalton, and the Mullet was Dalton.

Mullet-based humor is now so old that I remember having to make sure the audience knew what mullets were when I wrote a sketch about them for my comedy group in college—in 1998. That isn’t what this about. The very first shot of Dalton in Road House shows the back of his head for a reason.

Please note that the director of photography on this film is Dean Cundey. His credits as a cinematographer include Jurassic Park, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Back to the Future, The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, The Fog, Escape from New York—a murderer’s row of SFF classics from directors who convey story primarily through image and character through portraiture. The shot of Dalton’s mullet establishes him as recognizable first from behind, and then in silhouette. No one else in the movie has a head of hair anywhere near this magnificent and distinctive.

As the camera tracks in on Dalton, we watch him survey the crowd at the filled-to-capacity hotspot at which he currently works. He nods along absently to the beat of the music played by the band on stage, so absently in fact that his head tilts upward with the beat rather than downward. It reads more like a gesture of regal approval and command than a guy mildly rocking out, because that’s what it is. (He’ll make similar gestures a minute or two later, when he wordlessly instructs the bouncers in his charge in how to handle some ruffians.) At that moment, all is right with his world. The cooler has cooled.

Then things heat up. Dalton turns his face toward the camera and his eyes focus. A cut along his eyeline reveals what he’s looking at: a man soliciting a woman as if she’s a sex worker, putting a hundred-dollar bill down on the table for her services. Insulted, she takes out a knife and slams it downward, pinning the money to the table. Insulted in turn, the man kicks her chair right between her legs, tipping it over and knocking her on her ass. Bouncing and cooling ensue.

Pay close attention to the editing here, by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link. Between them, and sometimes in tandem, these men cut Die Hard, RoboCop, Predator, Commando, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Tombstone. They’re as responsible for establishing the rhythm and language of contemporary action-thriller cinema as any two people in the business. Do they cut from Dalton to the troublemakers once the trouble has started? No. They cut slightly before, after the sound of a single broken glass and a raised voice, in a jam-packed nightclub with a rock band playing.

Urioste and Link are not likely to have done this by accident. They’re establishing Dalton’s near-superhuman ability to detect, defuse, and defeat any bar’s bad element. They’re demonstrating what happens when his cooler-sense starts to tingle.

Thanks to these three top-tier filmmakers, Dalton’s mullet is as meaningful and memorable as Batman’s cowl or Darth Vader’s helmet.