Posts Tagged ‘emmet’

349. “This is our town, and don’t you forget it.”

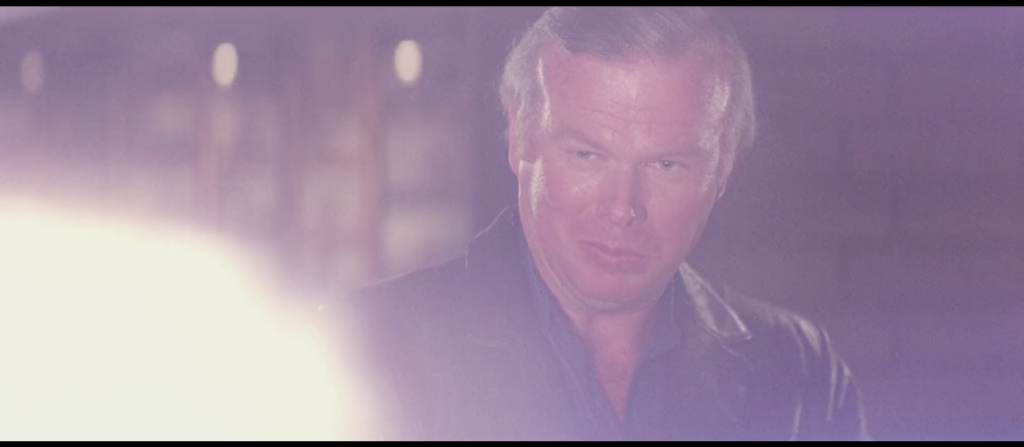

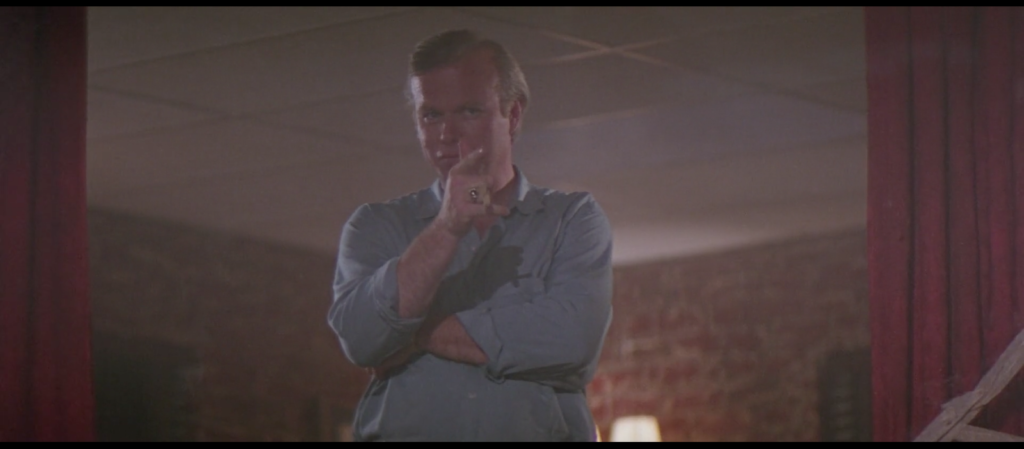

December 15, 2019Red Webster, Emmett, Pete Strodenmire, and Frank Tilghman have had enough of Brad Wesley. I mean, to put it mildly. Together they shoot him to death, though not before Tilghman turns Wesley’s “This is my town—don’t you forget it” back at him. The two men exchange a sort of slight smile after that. It’s the smile of men with secrets, if you ask me, though it would pass for an expression of resignation on one hand and triumph on the other to the layman.

Be that as it may.

The thing that strikes me about Brad Wesley’s death today is how quickly it follows the murder of his goons. The bodies of Morgan, O’Connor, Ketchum, and Pat McGurn are still warm, and Jimmy is probably just a few miles downstream, and blam blam blam blam, no more Brad Wesley. They were the iron fist with which Wesley ruled Jasper, from JC Penney to shining Fotomat. Take them away and the man is revealed as a paper tiger, albeit one capable of nearly murdering the best damn cooler in the business.

To put it another way, Brad Wesley fell when his goon squad was supplanted with another. Had Red, Emmet, Pete, and Tilghman joined forces earlier, perhaps they could have out-muscled Wesley’s muscle, or at the very least outgunned them. All they lacked was a fighting spirit, and Dalton gave that to them. It already was their town. All they had to do was rise up and claim it.

022. An elevator in an outhouse

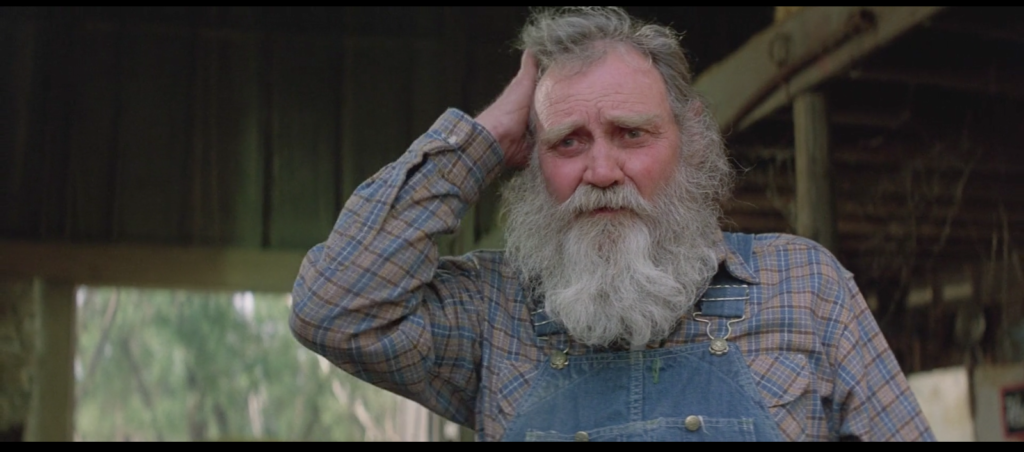

January 22, 2019“Callin’ me ‘sir’ is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse: It don’t belong.” So says Emmet, Dalton’s prospective landlord, to Dalton, Emmet’s prospective tenant, soon after they meet. Dalton is unflaggingly respectful to those his cooler-sense tell him deserve respect. Emmet, with his overalls and scraggly beard and extremely menacing hay-hooks, is such a fellow, hence Dalton’s use of that three-letter term of deference. Emmet in turn is determined not to put on airs, even at the expense of seeming less of an authority figure in the eyes of someone in whom he must trust to behave himself on their shared property on whom he will soon depend for income. In a minute or two he will rent Dalton a massive, fully furnished loft apartment for $100 a month, which is one-fifth of what Dalton makes every day, so he’s clearly willing to forego other markers of landlordism too. But in the meantime, an analogy that has never before passed the lips of man will have to do. I’d say it’s a singularly odd and vulgar expression to coin, but we’ve got “balls big enough to come in a dumptruck” and “does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick” and “I used to fuck guys like you in prison” to contend with in this film alone, so “singularly” is out. Still, this is our first taste of Road House‘s penchant for turning a phrase until it gets dizzy and collapses, and thus it’s a memorable one.

But it wasn’t until yesterday, writing about the sign that welcomes weary travelers to Jasper, that I got to thinking about how well the expression sums up the existence of Emmet and Dalton’s soon to be shared enemy, Brad Wesley. Like an elevator in an outhouse, Wesley represents the intrusion of commodification (as opposed to commode-ification) and technological overreach in the Jasper ecosystem. His house is the biggest house. His businesses are the biggest business. His goons are the biggest goons. His truck has the biggest wheels. Were he to construct an outhouse, an elevator is not out of the question.

What’s more, so many of his scenes are literal intrusions into places he does not belong: the opposite lane of traffic, the post-cleanup Double Deuce, the auto parts dealership run by the uncle of his ex-wife, Pete Strodenmire’s Ford showroom, and—most importantly, since the “elevator in an outhouse” exchange is bookended by it—the airspace above Emmet’s ranch. As Emmet and Dalton meet and negotiate, Brad buzzes them with a helicopter that, like his in-ground pool and his monster truck and (one presumes) his JC Penney, feels about as out of place in this environment as…well, you know.

Brad Wesley livin’ in Jasper is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse: He don’t belong. If you’ll permit me to take the analogy one step further: No matter how far up he may go, he’s still just a pile of shit.

013. Men look at Dalton

January 13, 2019When men look at women in Road House it means trouble. Steve the bouncer ogles his teenage would-be conquests. A husband with a cuckold fetish and a goofball barfly fetishize and fondle his wife’s breasts. A belligerent drunk starts a knife fight when people try to prevent him from watching his girlfriend dance on a table. Brad Wesley throws an absurd string-bikini pool party for his army of goons. A horned-up soldier rushes the stage in the topless bar where Wade Garrett works. Denise strips in front of the Double Deuce’s wolf-whistling bad seeds under Wesley’s approving eye in a strange act of macho-sexual judo. With two exceptions—the superimposition of the film’s title over an anonymous woman’s rear end, echoed by Wade hating to see Doc leave but loving to watch her walk away—the traditional male gaze is an indication that something is wrong.

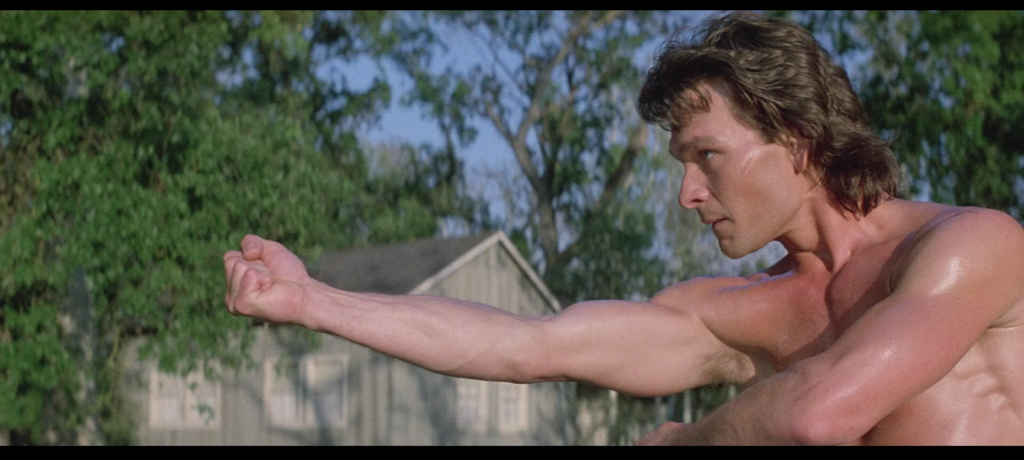

When men look at Dalton, it’s different. And men look at Dalton alright. All kinds of men, for all kinds of reasons.

When they first meet, goons like Karpis and Jimmy lock eyes with Dalton in staredowns that sizzle with psychosexual challenge. (In Jimmy’s case the sexual element is made abundantly, infamously clear later on in the film.)

Frank Tilghman stares at Dalton and smiles over and over again, like a man seeing his favorite meal on the way over to his table. “I want you,” he says during one such glance, followed in that same conversation with a knowing “I thought you’d be bigger.” “He’s good. He’s real good,” he says to another man during another. Honestly Tilghman is such a strange character that he probably deserves an essay series of his own, but his open near-worship of Dalton is a start.

Both Dalton’s friendly landlord Emmet and his evil neighbor Wesley watch Dalton perform tai chi, shirtless and slick with sweat. Wesley has the look you often see on the faces of men in movies who’ve caught a glimpse of a topless woman through a window. Emmet looks like he’s questioning a whole lot about the world and his place in it.

Wesley even watches Dalton and Elizabeth have sex. You might think that Elizabeth is the object of the gaze here, but at no other point in the film does Wesley bring her up as a point of contention between himself and Dalton, even though their relationship does seem to catalyze a new level of hostility between the two men. There’s no “she’s mine, if I can’t have her no one will,” and when he talks to her about Dalton it’s to express regret that she’s wound up with a lowlife drifter, not to threaten her to come back to him. He only has eyes for Dalton.

And honestly, who wouldn’t? Look at him.

By constantly showing us men who visually appreciate Dalton, Road House models behavior for its primarily male audience. Which is not to say women were not a target as well. Surely a decision was made to capitalize on the sex symbol status of the man who plays Dalton, Patrick Swayze, for the women in the audience—by then he’d starred in the smash hit Dirty Dancing, and another romantic blockbuster, Ghost, was on the horizon; his sex scene with Kelly Lynch set to Otis Redding beat the pottery scene with Demi Moore set to “Unchained Melody” to the punch.

But Road House‘s life since its theatrical release has been one of basic-cable afternoon screenings for dudes. I myself never caught it that way, but I first saw it during a Road House/The Warriors/The Road Warrior triple feature with a bunch of drunk and high friends, which is more or less the same idiom. I came away from my first viewing feeling just an unbelievable amount of affection and admiration for Patrick Swayze, an actor I’d never really thought about at all before. When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, I held a Road House/Steel Dawn/Point Break triple feature at my place and charged everyone a twenty-dollar donation to pancreatic cancer research for admission. I love Patrick Swayze just as I love Dalton. I believe these shots of men looking at Dalton, capturing the blend of admiration, envy, desire, and awe they feel when they look at him—call it the male swayz—are, at least in part, the reason why.

006. Church

January 6, 2019Emmet: It ain’t the money, you understand, but if I don’t charge you somethin’ the Presbyterians around here are likely to pray for my ruination. How does $100 a month strike you?

Dalton: Fine.

Emmet: You can afford that much?

Dalton: If it keeps you in the good graces of the Church.

Emmet: Ain’t it peculiar how money seems to do that very thing.

—Road House

David Brent: [singing] “Who is wrong and who is right? Yellow, brown, black or white?” The spaceman, he answered, “You no longer mind. I’ve opened your eyes—you’re now colorblind.” Racial. So,

—The Office

Aside from having His Name taken in vain, God doesn’t figure much into Road House. That’s worth paying attention to. In the roughly contemporaneous Rocky franchise Rocky wears a crucifix and often prays prior to a big fight, which particularly during his showdown with Soviet behemoth Ivan Drago takes on added political weight. Rambo is crucified in First Blood Part II. Yet despite a down-home setting conducive to that old time religion, the closest Dalton gets to spirituality by contrast is doing tai chi outside with his shirt off and referring to his study of philosophy at NYU as “man’s search for faith.” Though he and Dr. Elizabeth Clay do indeed meet when he goes to the hospital with one of the wounds of Christ—a stab in his side—it’s on the left side rather than the right, and rather than probe it, like Thomas, she seals it, like a doctor. No one’s making room for the Holy Spirit here, so to speak.

Played by “Sunshine” Parker, who was just 61 at the time of filming but looks like something hobbits might meet in an ancient forest, Emmet rents Dalton an outrageously huge and beautiful loft apartment open to nature with a view of the nearby water for one-fifth of what Dalton earns as a cooler every single night. He likes his horses and he likes company, and there you have it. Those are his wants and needs, and a few extra hundred dollars a month are superfluous. Why charge rent when it’s no skin off your ass not to? Why participate in a system that offers you nothing but things you don’t really need?

That this appears to be his attitude toward organized religion—and the film’s, since Emmet and Dalton are consistently portrayed as operating with unerring moral compasses, at least until Dalton commits the sin of despair at film’s end and pays for it dearly—is delightful to me. Sure, it seems thrown in there like it’s a David Brent–style attempt to open people’s eyes, as if anyone’s counting on Road House for enlightenment. But it works. There’s no Jesus, no Bible, not even any talk of praying to the Good Lord in his own way. There’s just a funny old codger summing up Christianity as a chauvinist capitalist scam. Brad Wesley with hymns, pretty much. When you’ve got the man himself to make your life miserable while singing “Sh-Boom,” who needs the hassle of godbotherers?

003. The Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri

January 3, 2019If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig. —Uilliam M. Bricken, Jr.

An English professor of mine used that self-reflexive riddle to illustrate the way Christ’s parables are both medium and message: The second the concept behind the parable clicks, so does the larger point about ethical behavior or spiritual enlightenment.

In his book The Three Christs of Ypsilatnti, psychologist Mark Rokeach recounts an experiment, which he would later apologize for and reject as unethical, in which he placed three men who believed themselves to be Jesus Christ in regular group therapy sessions in hopes that encountering each other would shatter their delusions, to which end he occasionally manipulated them directly by concocting imaginary elements of their collective story himself. The experiment was unsuccessful.

This man is Big “T” of Big “T” Auto Sales, or so it seems safe to assume. We meet him around 17 minutes into the film, as he watches The Patty Duke Show on his office television while preparing to eat his lunch. He then notices our hero, Dalton, checking under the hood of a beat-up old car in the lot. “She’s a runner!” shouts this walrus-looking sonofagun as he strides out to meet Dalton face to face, treating the singular requirement of any used car sale—that the car being sold is capable of movement—like a selling point. Dalton drives a Mercedes when he’s not on the job, but since angry patrons of the bars at which he serves as cooler tend to take their frustrations out on his car after they’re ejected, he replaces it with a cheaply bought beater when he’s got a gig. He takes the car. We never see Big “T” again.

This man does not have a name, not that we’re given to know anyway. We meet him about one minute after we meet Big “T.” This fellow presides over some kind of automobile junkyard Dalton goes to not to purchase a used car, which he could have done here since used cars are visibly on sale in the background, but to stock up on spare tires, since people who are pissed off that he smashed their face through a table because their girlfriend was dancing on another table often slash his tires in revenge. Dalton loads the trunk of his new old car with tires and gives the proprietor a little salute, which the old man returns. We never see this man again.

This man is Red Webster, proprietor of Red’s Auto Parts. We meet him around 33 minutes into the film, after which he becomes a major character. His store is the closest business to the Double Deuce, with which it shares some kind of vast dirt parking lot or road or whatever it is despite being about a football field away. His niece is Dr. Elizabeth Clay, former love interest of Brad Wesley and, soon, current love interest of Dalton. He is Dalton’s primary source of information on the protection racket run by Brad Wesley under the guise of civic improvement. Dalton goes to Red’s store to order a new windshield and buy a new antenna for his car after both were destroyed by angry ex-patrons of the Double Deuce the night before. This is the third scene in which Dalton makes an automobile-related purchase, and the third business establishment at which he does so. The movie is not quite 35 minutes old.

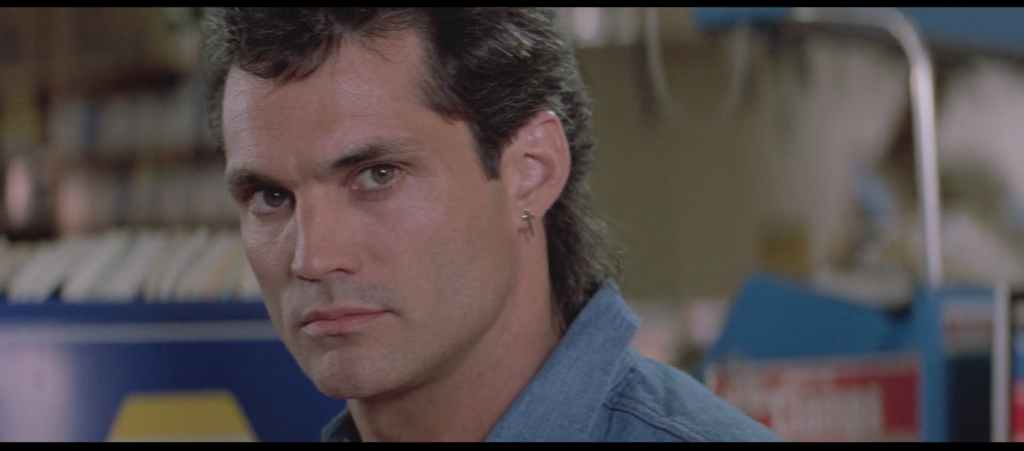

This man is Pete Strodenmire, proprietor of Strodenmire Ford. We meet him around one hour and 24 minutes into the film, at a hastily convened meeting of Jasper business owners, plus Dalton and Elizabeth, to discuss the prior night’s destruction of Red’s Auto Parts in an arson ordered by Brad Wesley. There are seven people at this meeting. Four are Dalton, Elizabeth, Dalton’s nominal boss Tilghman (seen above in the background), and Elizabeth’s uncle Red. The other three, including Strodenmire, are people we’ve never seen before; the two who aren’t Strodenmire have no lines, and we never see them again. The next time we see Strodenmire, Brad Wesley has ordered one of his goons to run over the man’s entire glass-enclosed showroom of new cars with a monster truck, which he does with glee. Strodenmire winds up being one of four men—along with Red, Tilghman, and Dalton’s nominal landlord Emmet—who murder Brad Wesley, the film’s antagonist, with shotguns during the climax. Again, we meet him an hour and a half into a two-hour film that has already included three other car or car-parts salesmen.

This man is Emmet. We meet him about half a minute after we meet the man from whom Dalton purchases tires, when he rents Dalton a barn-loft apartment that must have cost $50,000 dollars to build for $100 a month. He doesn’t sell cars or car parts, but you can see how he and the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri share a similar aesthetic.

Road House is a movie about a road house, that much is true. It’s not a movie about roads, however, nor about what you drive on them. (Much more time is spent showing Dalton buying cars, parking cars, and buying car parts to fix what happens to the cars after they’re parked, than is spent showing anyone actually driving cars.) Thus, the film’s maximalist approach to automotive retailers is striking, and bears contemplation.

Could Dalton’s trips to fully four different stores for his vehicular needs have been consolidated to, say, two, perhaps the ones owned by the two men who wind up saving his life from the character played by Ben Gazzara (John Cassavetes’s Husbands)? Yes.

Would this have been an easy way to establish Strodenmire, who I stress fires a shotgun into the body of the movie’s antagonist and inflicts a mortal wound, before the movie was three quarters of the way finished? Yes.

Would this have made things less confusing to people for whom men whose vibe is best described as “Old Fart” sort of blend together in an indistinguishable blur of ill-fitting work shirts and bold facial-hair decisions? Yes.

Is understanding that Road House has its protagonist make car-related purchases from three different men (two of whom are never seen again), includes a fourth as a main character when he emerges from a nameless scrum of unknowns when the movie is almost over (and who has never been seen before), and casts weird old coots in all four roles (with weird old coots to spare playing other parts)—that is to say, understanding things that makes no sense—key to understanding Road House‘s unique rhythm in all its concussive dreaminess?

If this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.