Posts Tagged ‘patrick swayze’

342. Mad Brad

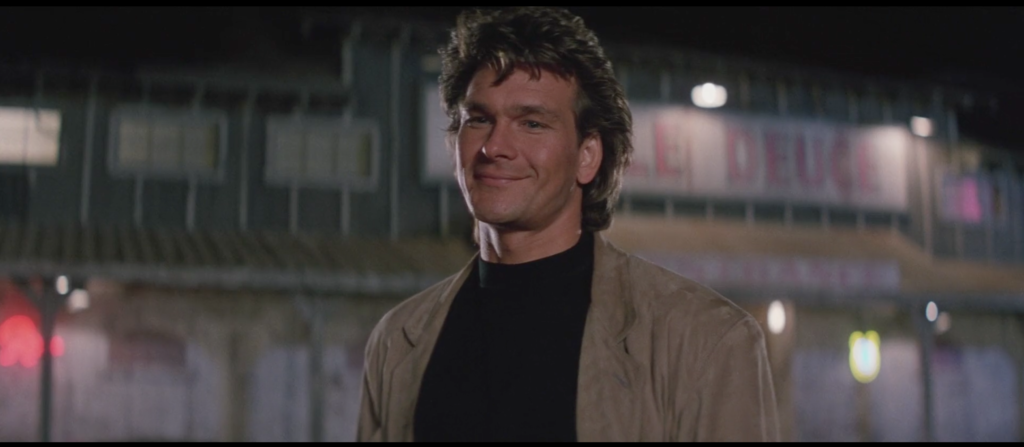

December 8, 2019In the middle of whipping the shit out of Dalton with a spear, Brad Wesley makes this face. His eyes all but bug right out of his head. His mouth is set in some sort of weird battle rictus. His usually impeccably coiffed hair is just wild enough to look upsetting in context. All in all it’s probably the right way to look if you are Ben Gazzara, age 58, and you’re supposed to be a convincingly formidable adversary to a trained dancer/fighter/stuntman/actor 22 years your junior. Fortunately for us, director Rowdy Herrington agreed, and a lingering shot of this absurd face made the cut when this fight scene was put into its final form. It goes a long way toward selling Wesley’s end of the bargain.

For his part, Patrick Swayze spends a long time just dodging rather than striking, rolling around on the furniture, avoiding Gazzara’s swipes and stabs with the spear. When he finally gets back on his feet he’s hunched over, his bullet-wounded left arm pulled in toward his body, a posture that conveys the fact that he’s badly injured and possibly also just worn down from murdering four other guys in the past three or four minutes. After seeing Dalton go toe to toe with the likes of Jimmy and emerge victorious, Road House had yeoman’s work to do in order to convince us that Dalton’s battle against Brad Wesley would be anything other than an embarrassing squash, and by god the film almost pulls it off.

323. Sublime/Faces of Death Redux

November 19, 2019I sometimes think of Road House as a sublime movie, and that’s not an adjective I throw around for movies that often. For me it’s reserved for films that transport me into a place of tangible, physical awe—the equivalent of musical frisson, that chill you get up and down your spine and through your skull from art that stuns you. If you know me at all it won’t surprise you to learn that I get this feeling most often from horror films. I think Jaws is sublime. I think The Exorcist is sublime. I think The Shining is sublime. I think Aliens is sublime. I think Hereditary is sublime. I think Barton Fink is sublime. You get the idea. So you get that Road House does not transport me the way any of those movies do.

Why is Road House sublime? Because sandwiched in between two identical parking scenes and a scene in which two lovers confront one another over matters of life and death in front of a bunch of x-rays of people’s colons, Patrick Swayze looks at Sam Elliot like he does above and below. First: total love, respect, humility—he is admitting he was wrong after all—and above all gratitude that he gets to know this man. Then: total loss, grief, anger, denial, anything but acceptance that this man who meant so much to him is gone.

The word I use to describe Patrick Swayze as an actor is generous. He gave himself over to this absurd role in this absurd film, used every ounce of his training as an actor and a professional-grade stuntman and a professional-grade ballet dancer. Every interview I’ve ever seen with Kelly Lynch or Marshall Teague or Sam Elliott in which they’re asked about this film is full of superlatives of how dedicated he was, and how kind he was, and how the experience of working with him was…well, they don’t say it, but I will: sublime.

Parking, acting, colons, parking, more acting, acting like his life has fallen apart, like the person he loves most in the world has been stolen from him. His eyes squint with tears and she shakes his head wildly back and forth, moving his whole upper body at one point, his whole self one gigantic No. Some of the dumbest filmmaking I’ve ever seen, and then this. Sublime.

211. A Tale of Two Tushies

July 30, 2019It was the best of bars, it was the worst of bars, it was the age of being nice, it was the age of not being nice, it was the epoch of balls big enough to come in a dump truck, it was the epoch of opinions varying, it was the season of Wade, it was the season of Wesley, it was the auto dealership of hope, it was the separate and unrelated auto dealership of despair, we had Wagon Days before us, we had Wagon Days underneath us, we were all going direct to Jasper, we were all going direct the other way.

200. The sex scene from Road House

July 19, 2019It looks uncomfortable, like it would strain his back and abrade hers. It looks lackadaisical, like two grown adults couldn’t be bothered doffing the oceans of loose-fitting fabric in which they’re garbed before starting. It sounds awkward, since the verbal foreplay in which the participants engage consists solely of the woman discussing her ex-husband and her uncle. It sounds incongruous, with all of the above soundtracked by the platonic-ideal lust and soul and yearning of Otis Redding’s “These Arms of Mine.” It feels abrupt, as their hands move to each other’s belt buckle and underwear before their lips meet, when a kiss has only been teased. It feels brazen, as she takes him inside herself/he puts himself inside her after the briefest gesture in a kiss’s direction. It’s intimate, this decision to make love while deliberately eschewing certain forms of intimacy as if superfluous to the intimacy already established. It’s silly, so much so that first she and then he laugh in the middle of it from the sheer sexy ridiculousness of it all. It’s hot, watching this process unfold from zero, seeing two beautiful people get horny, knowing what’s happening to his body and to her body as a result, watching them do what bodies in those conditions are designed to do. It’s right there in front of us, the camera bringing us up close against their faces, their hips, their hair, their hands, his undulating body, her grasping legs. It’s Patrick Swayze and Kelly Lynch having sex standing up against a wall made of huge rocks. It’s the sex scene from Road House. It stands alone.

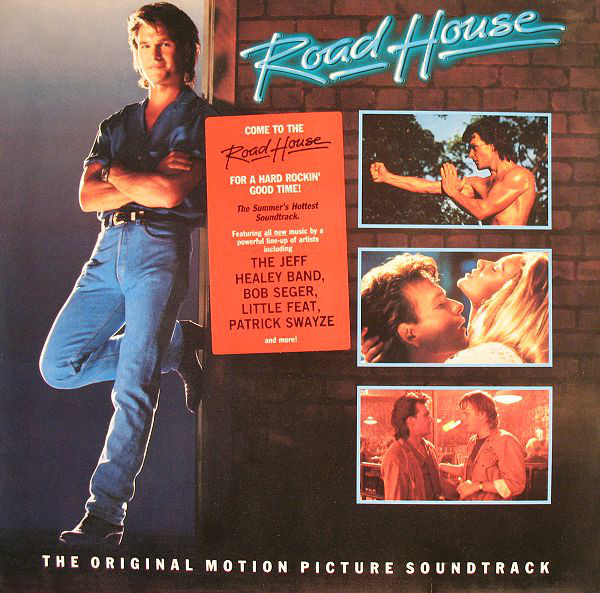

190. Soundtrack

July 9, 2019The thing you need to know about Road House: The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is that it’s not what you think, or perhaps even hope, it is. It’s not a wall-to-wall collection of all of the Jeff Healey Band’s performances from the film. Four of their songs make the cut, but one (“I’m Tore Down”) is only minimally memorable from the movie, and several of the big showstoppers (“Travellin’ Band,” “White Room,” “Knock on Wood (feat. Kathleen Wilhoite)” are nowhere to be found. There’s no snippets of the High Hollywood action-movie score by Michael Kamen, the late great film composer who counted the original Die Hard trilogy and Metallica’s orchestral album S&M among his achievements. “These Arms of Mine” by Otis Redding? That’s in there, thankfully. Alabama’s “(There’s A) Fire in the Night”? No joy.

What you get is a mixture. There’s those four Jeff Healey tracks, including “Roadhouse Blues” and “Hoochie-Coochie Man” from the Denise striptease and Bob Dylan’s self-plagiaristic “When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky.” Otis is on there. Most of the songs are covers—Dylan, the Doors, Willie Dixon, Willie Nile, Maria McKee by way of Feargal Sharkey, Fats Domino. There are at least four songs on here, including two performed (and one co-written) by Patrick Swayze himself, that I don’t think are in the actual movie at all.

You could complain about that, were you so inclined. Me, I’m happy to hear Patrick Swayze’s surprisingly high breathy singing voice over massive ’80s production tricks (giant drums, “ay-oh ay-oh” backing vocals, little glittery synth fills). And anyone who played Prince’s Batman album and Madonna’s Dick Tracy tie-in I’m Breathless as often as I did in middle school knows this much is true:

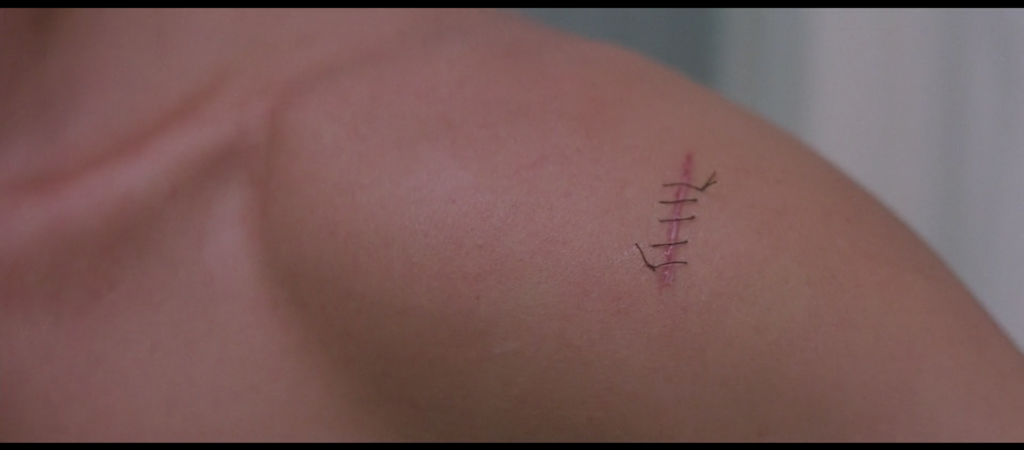

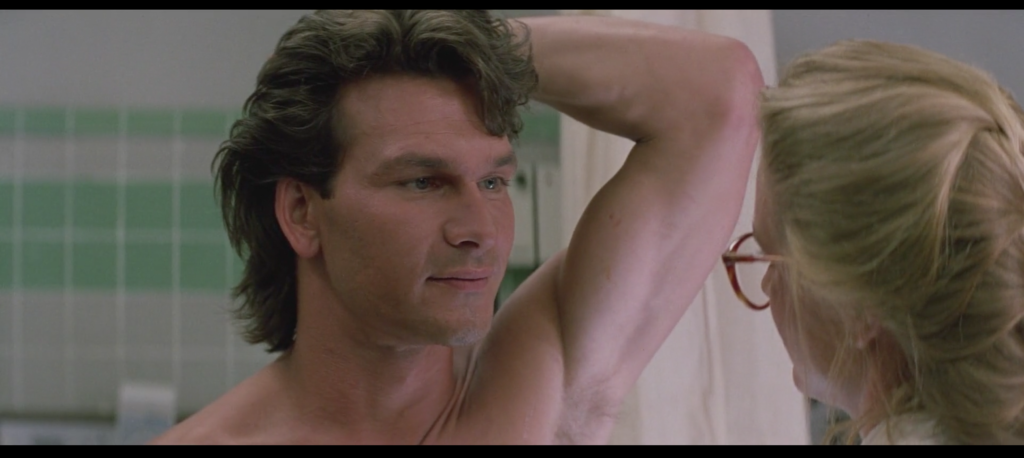

187. Stitches

July 6, 2019“Why must a movie be “good” ? Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a beautiful face, huge?” When Mike Ginn wrote this on twitter he could easily have been speaking about Road House, since the beautiful faces of Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, and Sam Elliott are no small part of the attraction and entertainment. (If you find a film studies program that articulates the sensual pleasure of cinema this effectively in two sentences or less, please ask a billionaire to give it a grant.) But in the action films of the 1980s—as in many other genres and many other time periods, but here the tendency is especially marked—there’s another question to ask: Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a beautiful face, bruised?

Sylvester Stallone is one of the strangest extremely famous and mainstream people in Hollywood. I often think of the road not taken when he put out Rocky II and thus gave the lie to the final exchange between Rocky Balboa and Apollo Creed about rematches in the first Rocky film, which would otherwise be remembered as the classic of 1970s New Hollywood that it actually is. But since he is often not just the star of his films but the writer and/or director as well, his idiosyncracies shine through in even the most fast-food slop he serves up. Regardless of how slick, bombastic, and ultimately jingoistic the Rocky and Rambo series wound up getting by the end of the ’80s, in direct opposition to the earthy, low-key, and questioning debuts, they are at heart two separate franchises created by Sylvester Stallone based on the assumption that watching his perfect body get destroyed over and over again was crackerjack mass entertainment. That he was correct speaks to a desire in the audience to see that which we desire abased and laid low. Kink has understood and articulated this forever; cinema can’t really speak it aloud, but it’s there alright.

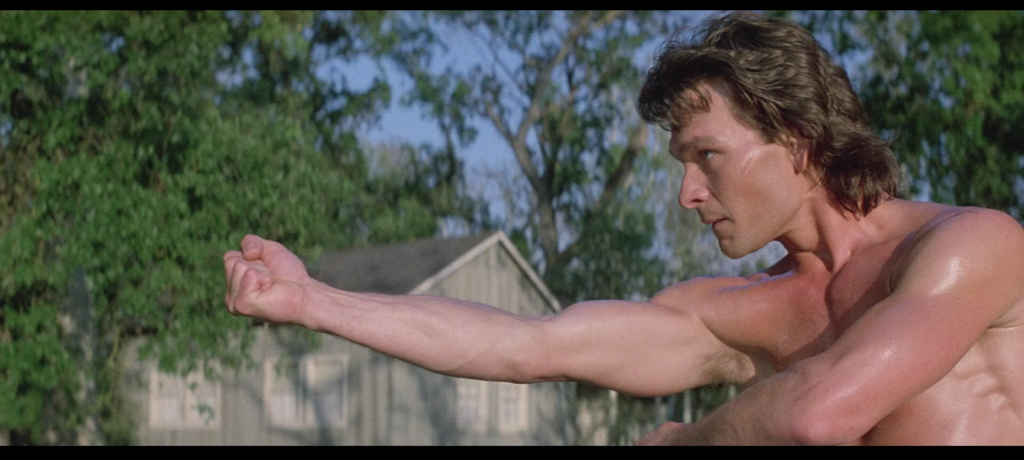

As I was flipping through my copy of Road House, which is often what I do to start this daily process, I stumbled across this frame of Patrick Swayze’s shoulder with a stitched-wound makeup effect stemming from Dalton mending the knife injury he incurred at the start of the film. At no point does Dalton take a beating that John Rambo and Rocky Balboa would even recognize as such. Yet because of his lithe dancer’s physique (“I thought you’d be…bigger”), the delicacy of his movements, and the coded-feminized prettiness of his face and hair, we feel the shit out of every punch and kick and cut. His penultimate battle, with Jimmy, is to my mind one of the best fight scenes ever filmed not just because of the ace choreography and Swayze’s and Marshall Teague’s almost dangerous commitment to the scene (they realized after the first night of filming that they’d have to pull some more punches if they wanted to successfully complete the damn movie), but because of how Swayze’s shirtless, glistening, fire-illuminated torso radiates physical beauty even as it’s getting pummeled into hamburger. The beating is the spice that brings out the flavor of the dish. So too here with the wound and the stitches, six bold slashes through an unblemished field of bare smooth flesh. The stitches could just as well spell “Kiss it and make it better.” So could the Hollywood sign.

131. Pain hurts

May 11, 2019“It is realistic, and we’ve been striving very hard to make it realistic. Fights aren’t pretty. You know, when somebody gets hit, it hurts, and it’s ugly, and we’ve tried to capture that.” —Rowdy Herrington

—

“I grew up in Texas—not that this is exclusive to Texas. But what is it about men having to go out to bars at night and beat somebody’s face in, or get their face beat in, and get drunk, and you know, they don’t care which it is? There’s some kind of anger or aggression in all of us that we have to find a way to vent or it’ll kill us. And that’s what intrigued me about this, because this script looked like everything I grew up with—every level of mentality that I’ve known since I was born.” —Patrick Swayze

—

“Do you ever win a fight?”

“Nobody ever wins a fight.”

—Dr. Elizabeth Clay and Dalton, Road House

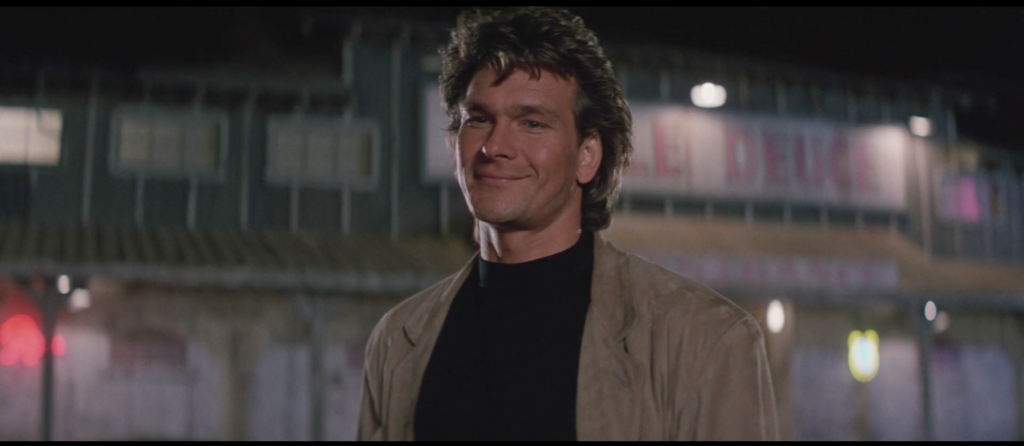

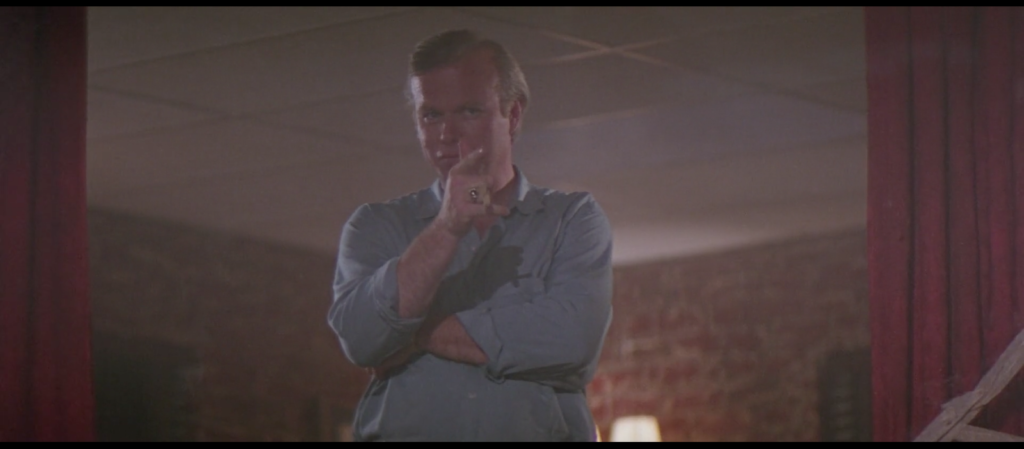

109. We’re not so different, you and I

April 19, 2019“What he says, goes.” “It’s my way or the highway.” “It’ll get worse before it gets better.” Few action-movie cliches go unuttered in Road House, along with several no action movie has ever used before or since. (“I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick.”) Remarkably, however, we never get a good “We’re not so different, you and I” out of Brad Wesley. There are moments when it seems he’s coming close—Mike Nelson notes this during the climax in his excellent solo RiffTrax on the movie, the first of three or four he and the other MST3K vets have recorded—and the Doc draws the parallel herself when things get really hairy, but the villain whose specialties are taunting Dalton and opening JC Penneys never goes there.

Given Rowdy Herrington’s direction, perhaps actually coming out and saying it would be gilding the lily. No, no one says “We’re not so different, you and I.” But in scene after scene both Dalton and especially Wesley react to annoyances and misfortunes with the exact same way. They cock their head to the side, shake it in “get a load of this” disbelief, and half-smile “ya just gotta laugh”–style. Dalton does it when he emerges from the Double Deuce after his first night of work and discovers his car has four flat tires, a broken antenna, and a shattered windshield (Nelson, in his RiffTrax again: “I have hours of backbreaking labor ahead of me. It’s actually pretty funny!”); Wesley does it the very next day when he spots Dalton practicing tai chi. You get variations on it for matters as minor (no pun intended) as Dalton finding Steve in flagrante with a young lady in the back room, and as grave as Wesley walking through his mansion and discovering the dead bodies of all his henchmen. Wade Garrett and Elizabeth may not do the head-shake thing but they spend the entirety of their three-person date with Dalton grinning at each other in that same can-you-believe-it way.

It can hardly be said that Ben Gazzara and Patrick Swayze have similar acting styles or training, so I can only assume this was Harrington’s go-to instruction, like George Lucas’s infamous “faster, more intense” on the set of Star Wars. But like so many of the film’s other foibles this winds up feeling both endearing and unique. Vandalism, tai chi, dead bodies, people fucking during their 15 minutes—Road House‘s reaction to each is “grin and bear it,” and there’s no other film with quite so untroubled an outlook on the totality of human experience. As Red Webster put it, “That’s life. Who can explain it.”

108. Dead man revisited

April 18, 2019“You’re a dead man,” Morgan tells Dalton when he gets fired. Carrie Ann, Morgan’s now-former coworker, may not share his idiosyncracies regarding where to place the emphasis when speaking, but she does share his sentiment.

The morning after Dalton’s momentous first night in the Double Deuce’s employ, Carrie Ann heads over to his luxury barn to feed him breakfast and, lucky for her, see his bare ass and reenact that gif of Ariel the Little Mermaid leaning on a rock as a huge gush of water erupts around her as a result.

But she brings business to go along with her culinary and visual pleasure. Firing Pat McGurn, one of the Double Deuce’s bartenders, is something Dalton should not have done, she tells him. As a mostly mute (but for grunting and an admittedly sincere-sounding “thank you”) Dalton sits down with a lit cigarette in his mouth and no shirt on his torso, disgustedly tossing aside the bacon and egg sandwich or whatever it is she brought him and moving in on the coffee, Carrie Ann starts cracking up while saying “Oh my god.”

“What is the joke,” Dalton asks, sounding like a cop on a TV show who just got a call at 3:30am saying there’s been another homicide down at the docks.

“Well, there’s no joke,” Carrie Ann says. “I just think I’m looking at a dead man, though.”

“Seems everywhere I go I hear that same joke,” Dalton mutters, shaking his head.

“Yeah? Well, something tells me you bring it on yourself,” Carrie Ann says saucily, nibbling on her breakfast in eating the popcorn/sipping the tea mode.

The variation in affect between the two actor makes it tempting to write this scene off as a minor bit of light-comedy character building. Dalton, who is hung over from a long night reading A River Runs Through It, is gruff and world-weary, too tough to worry and too tired to care. This is just how he lives his life: an endless cycle of naked wake-ups, shirtless stretching, cigarette-flavored coffee for breakfast, some tai chi or perhaps hitting the heavy bag for a workout, grabbing an unstructured jacket, heading to work to get stabbed by various men in the course of kicking their asses, repairing the damage done to his car by those men on their way off the premises, driving back to his luxury bachelor pad right next to the horse pen, taking off his shirt, reading a book, spying on Brad Wesley’s in-ground pool orgy, and finally doffing his jeans and hitting the sack. If during the course of those events people pronounce him a dead man, it’s a job, it’s nothing personal. And Carrie Ann is just the platonic female foil, the funny best friend, who’s able to poke holes in his machismo but not actually call his narrative into question or anything of that threatening nature.

But Carrie Ann, the drinking man’s Cassandra, also knows well that the only person who can truly save Dalton is himself. A warning out of professional courtesy, a gesture of solidarity with a new friend, an excuse to go over to the hottest guy in town’s place—it’s probably all three of these things. But in reality what he’s saying is “I can’t help being what I am,” as a stoic positive; she’s saying it too, but as a cheerily black-comic negative. Worst of all, it’s a direct challenge to the Rules. All that talk about expecting the unexpected, remembering it’s a job, it’s nothing personal, be nice until it’s time to not be nice, watch my back and each others’, and so on…earns him death threats “everywhere I go”? Okay dude, her twinkling eyes and cocked head seem to say, it’s your funeral. We’d expect no less of a dead man.

107. Dalton’s back

April 17, 2019Broad-shouldered, slim-waisted, corded with muscle, Dalton’s back is a perfect thing, an inverted arrowhead of sex. The sun glistens and gleams from every sweat-soaked ridge and cleft. At times you’d swear it’s a source of light itself. The camera orbits Dalton throughout his riverside tai chi routine and his whole body, or at least the upper half which is mostly what you see, is a marvel of course. But his back looks like it was manufactured, by the company who designed the clockwork opening credits for Game of Thrones maybe, or the people who adapted H.R. Giger’s artwork into sculptures for his house. During his waterside tai chi routine both Emmett, his friend, and Wesley, his enemy, stop what they’re doing and just…stare. It’s impossible to blame them. Or us. Dalton’s character is built on the sense that his many aspects—fighter, lover, road warrior, philosopher, rich famous guy, aw shucks everyman, killing machine, pacifist, beer-drinker, binge-reader, master, apprentice—all work in concert to make the man. Road House too, when appreciated properly, is less a film than an ecosystem: hyperefficient factory-made late-’80s star vehicle, barely competent incoherent MST3K fodder, rock-solid action flick, more obvious than usual homoerotica, smarter than it looks, dumber than it realizes, a Ben Gazzara film, a Terry Funk film. When you watch Dalton’s flawless, godlike arms and traps and shoulderblades flex and contract in harmony, you’re watching the character and the movie in metonymy. You’re watching a real physical thing, Patrick Swayze’s beautiful beautiful body, do what Patrick Swayze’s character and Patrick Swayze’s movie are also doing. As below, so above.

064. I Thought You’d Be Bigger Vol. 1: Tilghman

March 5, 2019At the end of their first encounter Frank Tilghman tells Dalton “I thought you’d be bigger.” This is Road House‘s primary recurring joke; you’ll hear it two more times from two other people. It’s probably swiped from everyone telling Snake Plissken “I thought you were dead” in Escape from New York, for what it’s worth. It’s a groaner, and it’s endearing in its groanerness over time.

It is also a weird thing to say to someone you just met. It’s a weird thing to say even if they’re a person whose job is usually associated with being of a certain size. Imagine meeting a professional wrestler or basketball player and saying that: You can picture the mechanical smile and hear the canned response already, right? Because chances are it’s not the first time the person in the job usually performed by a bigger person has been made aware that they are, comparatively speaking, smaller. It’s more likely that they’ve thought about this for literally decades, like since they were in first grade, than that this charming bit of banter will catch them delightfully unawares.

Frank Tilghman is a weird guy, though, whether by design or by Kevin Tighe’s inability to play him any other way. (A reader I’ve since argued with because I think it’s more likely Steven Spielberg has cinema’s best interests at heart than Netflix does suggested he auditioned for the Brad Wesley part, got Tilghman instead, and simply decided to play the role as Brad Wesley anyway, and it’s a damn good theory.) If you could dress a leer up in a bolo tie, that’s Frank Tilghman. He looks like a police sketch based solely on an eyewitness saying “He was some kind of pervert.” If you can watch him during the opening of this movie and not assume he’s the villain of the piece, I think that constitutes a Turing test failure.

Nevertheless he is one of the good guys, he has no ill intent toward Dalton, at no point does he do anything to antagonize or undermine or bamboozle or even overtax Dalton during his employment at the Double Deuce. This only makes “I thought you’d be bigger” even weirder.

Yet the way he says it is the weirdest thing of all, way more than the mere fact of saying it. He’s closes a deal bringing the best young cooler in the nation into the fold for a cool mid-six-figure salary, with no set start date. He does this while watching Dalton a) stitch himself up from a knife wound Tilghman also watched him incur minutes earlier, and b) summarily quit his current job while treating the owner of the bar he’d worked in like dogshit. And what does he do on his way out the door but pause, flash that unmarked-van grin, and say “You know, I thought you’d be…bigger.” The ellipsis represents a pause so pregnant with implication and innuendo its water is breaking, and the emphasis on bigger is definitely in the original, and did I mention he literally looks Dalton’s shirtless body up and down as he says this?

Now then. Do we have reason to believe Tilghman lusts after Dalton? Yes: Dalton is reason enough for anyone to lust after Dalton. Do we have reason beyond that? Yes: My theory that he and Pat McGurn were at one time involved romantically for one thing, or my other theory that the mysterious fortune he’s suddenly come into that allows him to renovate the Double Deuce and hire Dalton to keep the place secure came from an old rich widow he seduced as a closeted gigolo, persuaded to change her will to make him her sole beneficiary, and then tossed over the railing of a cruise ship, like the “Not great, Bob!” storyline from Mad Men, would (if true) indicate he is attracted to men and also makes destructive decisions in that regard. Are we intended to read his “I thought you’d be…bigger” as both a come-on and a sexualized dick joke? Yes: Our eyes and ears are not lying to us.

Do we need to respond with the kind of gross shitty gay-panic laffs we might have expected from movies and audiences alike for decades prior to this film’s release and at least a couple decades after it? No! The proper way to respond is this. First, to paraphrase RiffTrax’s Mike Nelson, the question of whether Kevin Tighe is trying to bed down Patrick Swayze, or the character equivalents of same, is a fascinating one on its face. It’s like when you learn Kate Beckinsale has a kid with Michael Sheen, which many people just learned when they also learned Kate Beckinsale is fucking Pete Davidson, the Saturday Night Live lotto winner who was previously fucking Ariana Grade. “A lot going on here,” I believe is your American expression, yes?

Second, and more importantly, this is a workplace safety issue, because Frank Tilghman absolutely is sexually harassing his new employee here before his first day on the job! Frank Tilghman may be on the side of the angels where the larger war for the soul of Jasper, Missouri is concerned, but he is without question an awful boss. Remember that before Dalton, Tilghman’s hires (that we know of) include two Brad Wesley goons and an extremely surly and obvious coke dealer and a guy who allows teenagers into the bar so he can have sex with them. The fish rots from the head.

Seen in this light, “I thought you’d be…bigger” becomes more than a come-on or a dick joke. It’s a cry for help. Frank Tilghman knows the magnitude of the task ahead of him—not cleaning up the Double Deuce, that’s just a metaphor, but cleaning up Augean stables of his very soul. To Tilghman, that is Dalton’s true task. Beneath the clumsy curiosity about his new hire’s penis lies the real question: Is he man enough to make me whole?

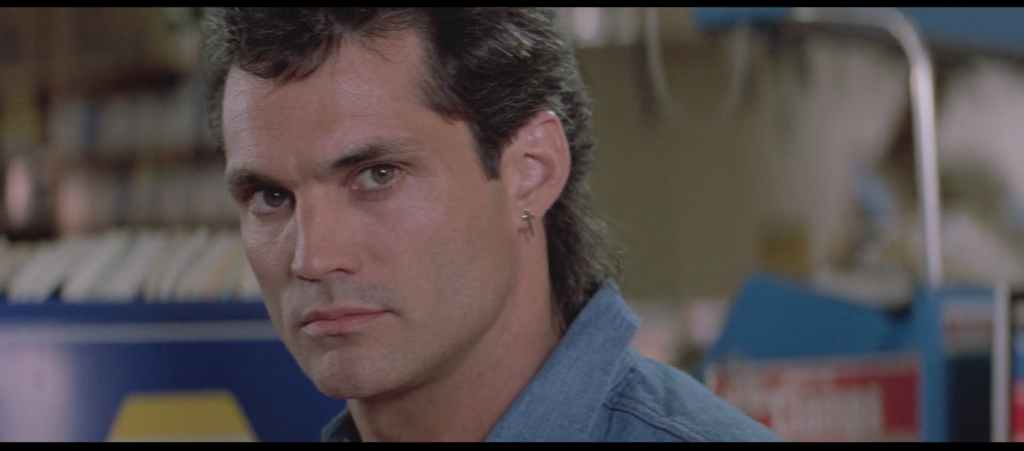

063. Patrick Swayze Beating the Shit out of John Doe from X

March 4, 2019Road House is a film in which Patrick Swayze beats the shit out of John Doe from X.

It’s simple, really. Sister-son Pat McGurn returns to his former place of employment with his uncle’s most useless enforcers O’Connor and Tinker in tow in order to force proprietor Frank Tilghman to reverse the decision of the bar’s new cooler Dalton and reinstate him to his position of bartender. Dalton takes very mild issue with the plan. Pat whine-gloats like a petulant child who thinks their parents are gonna punish their little brother and not them, then produces a knife the size of a machete and proceeds to simultaneously slash at and gay-panic taunt Dalton. Dalton punches his nose in. While he holds his hands to his broken face and howls in pain, Dalton spin-kicks him through a plate-glass window. He remains incapacitated for the duration of the fight that ensues, after which he is bodily carried out of the bar.

Concerned that Pat McGurn didn’t receive enough punishment? I’ve got you. First it’s important to note that by the end of the film Dalton will murder Pat McGurn, using the body of a dying goon to block Pat’s shotgun blast, then withdrawing the knife he’d inserted into the now dead goon’s gut and throwing it into Pat’s chest, causing him to misfire one last time and then plummet from a second-story landing to the ground below. Second you’ll notice from those screenshots that Pat’s nose was already bleeding before Dalton’s punch connected; you can call this slapdash continuity if you want, but I prefer to believe that either his body anticipated the damage that was about to be done to it and started hemorrhaging spontaneously, or that Dalton caused him to bleed without touching him by sheer force of chi. Or both! I’m not picky.

But here’s the bottom line, friends: Road House is a film in which Patrick Swayze beats the shit out of John Doe from X.

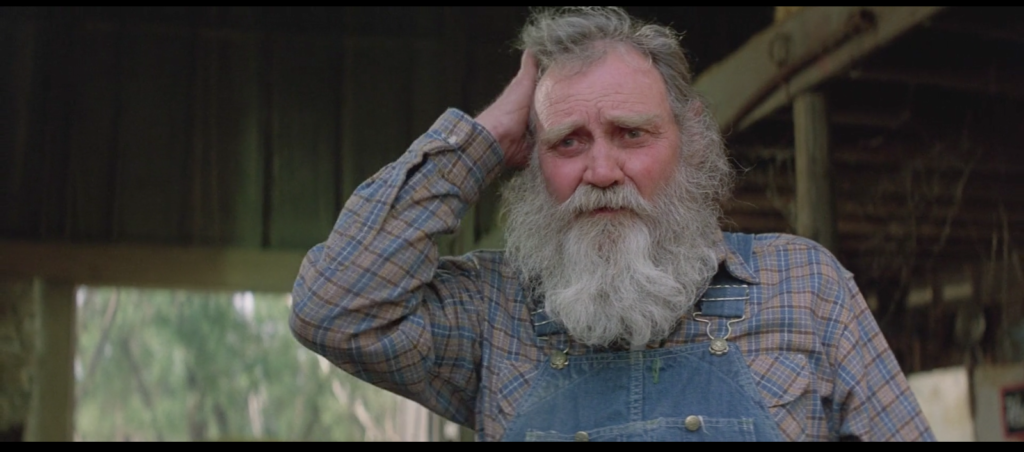

033. Dead man

February 2, 2019When Dalton fires Morgan, the irascible bouncer played by pro wrestling legend Terry Funk, from the Double Deuce because he doesn’t have “the right temperament for the trade,” Morgan reacts as if determined to prove this was the right decision. “You asshole,” he growls. “What am I supposed to do?” “There’s always barber college,” Dalton deadpans in reply. The rest of the staff laugh at Morgan then, openly and for what I’d imagine is the first time. Dalton has defanged him.

Pointing his finger in Dalton’s face, Morgan delivers his farewell prediction: “You’re a dead man.” He nearly smacks his severance check out of Tilghman’s hand as he grabs it, then storms away.

Road House fans—Roadies—enjoy this interaction a great deal. It’s at least partially obvious why: How often do you get to see Patrick Swayze (Dirty Dancing) and Terry Funk (Halloween Havoc ‘89) tread the boards together? But it’s Funk’s innovative line readings that make this a standout scene.

He previews the direction he’s headed when he calls Dalton an asshole, which he pronounces “asshole,” emphasis very much on the second syllable and, one assumes, that particular aspect of the anatomy. Two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response, right? For Morgan—and he’s not the only person in the film to pronounce the word in this way—”hole” is the lead noun, not “ass.” In his eyes, Dalton is less the cheeks than the evacuating void between.

Still, this might have escaped notice were it not for the coup de grace: not “You’re a dead man,” as every other person in the history of the English language has pronounced it, but “You’re a dead man.” Here, the rationale is a bit harder to parse. Surely no matter what spin you put on this, dead is the most important, and insulting, aspect of the phrase, right? Dalton already knows he’s a man. Dead is the newsworthy part. And in making himself the bearer of this bad news, Morgan is issuing a threat. (This is all obvious, I know, but we’re being methodical.)

So why emphasize “man”? Not to praise Dalton, that’s for sure, despite the rubric established by asshole. He’s putting man front and center in the Shakespearean, “What a piece of work is” way. If we think of Dalton as a man, a human, we imagine all that entails: his infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood; his need to breathe, eat, drink, sleep, excrete; his social and biological drives to form community and find a mate; his hopes and fears and lusts; his prodigious skill and significant renown as a bouncer-philosopher; his future in all its possibility and inevitability. One pissed-off ex-coworker later and this could all be gone, a man reduced to meat and thence to nothing at all. In his own dimwitted way, from a brain that processes only rage and schadenfreude, Morgan is driving home what Dalton stands to lose, and what he plans to take away.

020. Nothing personal

January 20, 2019“I want you to remember that it’s a job. It’s nothing personal.” We’ll be exploring of Dalton’s three simple rules for bouncing my Jasper road house in depth as the year progresses, but this elaboration of Rule Three, “Be nice,” bears scrutiny here in this early stage of the game. If you want to know what Dalton’s about, you need to see how seriously he takes not taking things personally. For now.

On Dalton’s first night on the job—the night of the Giving of the Rules—he makes a lot of enemies. He fires Morgan the bouncer for being a rat-bastard sadist and Pat McGurn the bartender for stealing from the register; both these men are members of the Wesley outfit and will repeatedly attempt to murder Dalton for costing them their jobs at what is, let’s face it, a complete shithole. He fires Steve the bouncer for having sex with teenagers on the job and he fires Judy the waitress (not that anyone ever says her name in the movie, of course) for dealing drugs on the job; neither shows up again but it’s hard to imagine losing their sexually and/or financially lucrative side hustles along with their day jobs sits particularly well with them. He also encounters a man who reacts to being asked to escort his girlfriend off the table she’s dancing on by whipping out a switchblade and threatening to stab a bouncer to death, and uses this man’s face to break a separate table in half before throwing him out; provided he hasn’t suffered a brain injury, my guess is he’s pissed off about it.

So there’s no surprise, and no shortage of suspects either, when Dalton walks outside and sees that his new car has had its windshield shattered, its antenna broken, and all four of its tires slashed.

Dalton saw this coming, of course. As previously mentioned, he makes it a habit to buy a beat-up used car while he’s working, knowing how the people he alienates tend to react. But this isn’t grudging acceptance of a bad situation, the way you might grumble standing on line at the grocery store the night before a big snowstorm. When Dalton sees what’s been done to his car, which will require him to jack and replace all four tires at a minimum before he can even think of addressing the other problems, he simply smiles and shakes his head. He’d shoot the same you-gotta-laugh look if he had a toddler who just covered her hair with peanut butter.

This is the face of a man who has a job, who does the job, and who does not take the job personally. His background in philosophy might help. Same with his study of tai chi. And in general he reverts to “laid back” as a default setting when external stressors are absent. And I mean that literally: When Wesley sends his goons Tinker and O’Connor, who recently tried to murder him and got their clocks cleaned for their troubles, to fetch him for a sit-down, he’s lying on the car that their fellow goons most likely vandalized the way a normal person might relax on a hammock.

But the “it’s a job, it’s nothing personal” thing is crucial to understanding the transformation Jasper, Missouri forces him to undergo. With each scene, you can watch his progress from one end of that spectrum to the other. Just know that this is where he starts.

014. Carrie Ann looks at Dalton

January 14, 2019I’ve been saying this for years, but it’s risky to write about what turns you on. When I first started reading the work of the woman who’d eventually become my partner it was hot in such a raw, unvarnished way—to me anyway, which explains a lot about what happened afterwards—that I wondered if she felt particularly bold or scared or vulnerable just putting it out there. Sex scenes are one thing, pretty much everyone who has sex enjoys it and even people who don’t usually enjoy watching it. But sex scenes, or scenes of sexuality, that tease out or revolve around a specific fetishized behavior aside from the basic forms of erogenous-zone contact or what have you…writing that stuff, or writing about that stuff, is in its own way as revealing as taking off your clothes.

Anyway, the scene in which Double Deuce waitress Carrie Ann sees Dalton nude is the single most erotic thing I’ve ever seen in a movie.

Played by Kathleen Wilhoite in one of the film’s least bizarre, most straightforwardly fun performances, Carrie Ann is what might have been called in earlier times a broad. She’s got a great brassy voice that she uses to dress down the Double Deuce’s belligerent bad element when Dalton first arrives and needs to get the lay of the land, eg. “Don’t let him bahhhther yew—Morgan was born an asshole and just grew bigger.” She’s the only female member of the core cast we ever see throw hands, when she smashes a bottle over a dude’s head during the movie’s first big brawl. Later in the film she’s revealed to have a terrific blue-eyed-soul voice, which she demonstrates by taking lead vocals for the Jeff Healey Band’s cover of “Knock on Wood.” (“I didn’t know she could sing!” announces the most adorable member of Dalton’s bouncing crew as the two men look on, grinning from ear to ear.) During the early-morning breakfast-delivery run she makes to Dalton during this scene, she’s mostly there to dispense greasy food and hard truths about the trouble he’s getting himself into at the bar, with a fuck-em-if-they-can’t-take-a-joke smile on her face the whole time.

That’s what makes her reaction to Dalton’s bare ass, and implicitly other parts, so powerful. This beautiful man’s naked body strikes this seen-it-all chatterbox dumb.

And like, on one level, yeah, of course it does. I mean, look at him.

Carrie Ann isn’t the only woman bowled over by Dalton’s attractiveness—you’ll recall, perhaps, Denise sizing him up—and she’s certainly not the only person to look at him in this way either. Indeed, the way women look at Dalton is largely indistinguishable from how men look at him, which is part of why the “male swayz” is such a standout phenomenon. The gaze of Carrie Ann, Denise et al conditions us for the gaze of Emmet, Wesley, Jimmy, Karpis, Tilghman and so on.

But no one looks at Dalton the way Carrie Ann does, because she’s the only person we ever see looking at him naked. (Dalton and Elizabeth are fully clothed when they start having sex; when they go for round two in the nude, it’s shown from a distance. We never see what Doc looks like when she looks at her man’s bare body.)

Carrie Ann shows up with breakfast the night after Dalton cleaned house at the Double Deuce, waking him up. He moans and groans and staggers out of bed like he’s hung over, which is funny since after he got home from work all he did was look across the way at Brad Wesley’s pool party in between chapters of the Jim Harrison novel he stayed up late reading. (For real.) But he sleeps in the buff, so when he slips out of bed, there he is.

Carrie Ann stops seemingly in mid-thought, like a rabbit in the headlights. Her eyes glaze. Her mouth opens. She gasps audibly. Her eyes heat up and a smile of pure horned-up delight briefly crosses her lips. Finally, she controls herself and looks away, abashed. There’s one final double entendre when he asks her how she tracked him down—”So how’d you find me?” “Oh! I, uh, it wasn’t too hard. I mean…you know what I mean.”—and by then he’s put on his jeans and begun his morning stretching-and-smoking routine. The scene moves on.

But I sure haven’t. Carrie Ann experiences something very rare for women in film: a moment of unguarded lust and guileless sexual objectification of the male body. She’s not doing this for Dalton, or even with Dalton’s observation and reaction in mind, since he’s not looking at her and has no idea what she’s doing. She stares and gasps and grins at him for no one’s entertainment or arousal but her own. Indeed, she’s sure to cut things off before he has a chance to notice and react. Perhaps this is done for his benefit, so as not to embarrass him, or for her own, so as not to embarrass herself. But the effect is that of a woman experiencing sexual desire in a totally personal, private, inviolate way.

What does this mean for us? We become voyeurs of another person’s voyeurism. And because her voyeurism is so accidental and unexpected, there’s a purity to it that avoids the fetish’s usual connotation of sleaze or outright violation, which lets us off that particular hook in turn. Without anyone trying, she gets to see something that turns her on, and we get to see her get turned on, and then it’s over. The eroticism of the moment is brief and blameless and beautiful. The fact that Carrie Ann is herself lovely helps, but it’s almost incidental. Arousal is lovely. Desire is lovely. And here they are, embodied in a moment and preserved, as in amber.

013. Men look at Dalton

January 13, 2019When men look at women in Road House it means trouble. Steve the bouncer ogles his teenage would-be conquests. A husband with a cuckold fetish and a goofball barfly fetishize and fondle his wife’s breasts. A belligerent drunk starts a knife fight when people try to prevent him from watching his girlfriend dance on a table. Brad Wesley throws an absurd string-bikini pool party for his army of goons. A horned-up soldier rushes the stage in the topless bar where Wade Garrett works. Denise strips in front of the Double Deuce’s wolf-whistling bad seeds under Wesley’s approving eye in a strange act of macho-sexual judo. With two exceptions—the superimposition of the film’s title over an anonymous woman’s rear end, echoed by Wade hating to see Doc leave but loving to watch her walk away—the traditional male gaze is an indication that something is wrong.

When men look at Dalton, it’s different. And men look at Dalton alright. All kinds of men, for all kinds of reasons.

When they first meet, goons like Karpis and Jimmy lock eyes with Dalton in staredowns that sizzle with psychosexual challenge. (In Jimmy’s case the sexual element is made abundantly, infamously clear later on in the film.)

Frank Tilghman stares at Dalton and smiles over and over again, like a man seeing his favorite meal on the way over to his table. “I want you,” he says during one such glance, followed in that same conversation with a knowing “I thought you’d be bigger.” “He’s good. He’s real good,” he says to another man during another. Honestly Tilghman is such a strange character that he probably deserves an essay series of his own, but his open near-worship of Dalton is a start.

Both Dalton’s friendly landlord Emmet and his evil neighbor Wesley watch Dalton perform tai chi, shirtless and slick with sweat. Wesley has the look you often see on the faces of men in movies who’ve caught a glimpse of a topless woman through a window. Emmet looks like he’s questioning a whole lot about the world and his place in it.

Wesley even watches Dalton and Elizabeth have sex. You might think that Elizabeth is the object of the gaze here, but at no other point in the film does Wesley bring her up as a point of contention between himself and Dalton, even though their relationship does seem to catalyze a new level of hostility between the two men. There’s no “she’s mine, if I can’t have her no one will,” and when he talks to her about Dalton it’s to express regret that she’s wound up with a lowlife drifter, not to threaten her to come back to him. He only has eyes for Dalton.

And honestly, who wouldn’t? Look at him.

By constantly showing us men who visually appreciate Dalton, Road House models behavior for its primarily male audience. Which is not to say women were not a target as well. Surely a decision was made to capitalize on the sex symbol status of the man who plays Dalton, Patrick Swayze, for the women in the audience—by then he’d starred in the smash hit Dirty Dancing, and another romantic blockbuster, Ghost, was on the horizon; his sex scene with Kelly Lynch set to Otis Redding beat the pottery scene with Demi Moore set to “Unchained Melody” to the punch.

But Road House‘s life since its theatrical release has been one of basic-cable afternoon screenings for dudes. I myself never caught it that way, but I first saw it during a Road House/The Warriors/The Road Warrior triple feature with a bunch of drunk and high friends, which is more or less the same idiom. I came away from my first viewing feeling just an unbelievable amount of affection and admiration for Patrick Swayze, an actor I’d never really thought about at all before. When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, I held a Road House/Steel Dawn/Point Break triple feature at my place and charged everyone a twenty-dollar donation to pancreatic cancer research for admission. I love Patrick Swayze just as I love Dalton. I believe these shots of men looking at Dalton, capturing the blend of admiration, envy, desire, and awe they feel when they look at him—call it the male swayz—are, at least in part, the reason why.