Posts Tagged ‘cars’

057. “It’s my way or the highway.”

February 26, 2019Dalton, during the prologue of The Giving of the Rules: “It’s my way or the highway.”

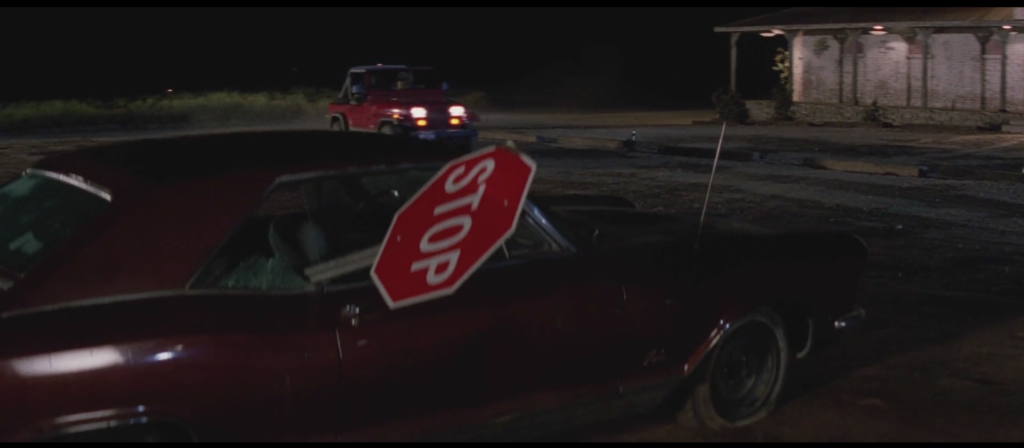

The highway:

Show me the lie.

Whether by accident or design—who can say? alright I can say, it’s by accident—there is no aphorism, no catchphrase, no idiomatic expression, no imbecilic threat or come-on or dick joke in the entirety of this film that does not bear close, even literal, reading. This is what I want to impress upon you more than anything else. This is what inspired this project: the sense that in the 15 years I’ve been watching this movie I haven’t touched bottom any more than you might during a swim in the middle of the ocean. Road House is a journey of discovery, a highway if you will, and the higher you fly the deeper you go the deeper you go the higher you fly so come on come on come on it’s such a joy.

032. Sh-Boom

February 1, 2019Originally recorded by doo-wop group the Chords, who charted with it in 1954, “Sh-Boom” became part of the pop-culture firmament largely because of a cover version by the Crew Cuts that was also a hit later that year. Both versions are the kind of gleeful pure-dee nonsense that make doo-wop such a fun genre to pronounce, let alone listen to. While Chords’ rendition has a jaunty swing to it, the Crew Cuts’ whitebread revamp emphasizes the gliding, carefree, “life could be a dream” side of the song. It sounds like a Sunday drive.

Of course, most people content themselves with driving on the right side of the road, Sunday or any other day, whether they’re listening to “Sh-Boom” or “Yakety Yak” or “Symphony of Destruction” by Megadeth. This is not just because it’s the law, or because it’s much safer not to drive into oncoming traffic. It’s because staying in your lane allows you to chart a long straight course, and a long straight road is the most fun kind to drive. The Germans modeled a whole genre of music after it and everything.

When we see Brad Wesley driving his red convertible (a Ford, possibly ill-gotten from Strodenmire’s ill-fated Ford dealership) with the top down on a bright sunny day, the fact that he’s singing “Sh-Boom” fits. It’s that kind of song. Wesley is also swerving from one side of the road to the other and back, over and over, like a sine wave, like a snake. This, too, fits. He’s that kind of person. But the actual driving process deserves closer examination.

Until Dalton passes by headed in the other direction, nearly getting run off the road in the process, there isn’t another car in sight. Wesley has the road all to himself. He could comfortably cruise along, taking in the air and the scenery. He could floor it if he felt the need for speed. (“He’s go the sheriff and the whole police force in his pocket,” Red Webster tells Dalton later in the film; the line is likely intended to explain why crimefighting in Jasper is entirely the province of bouncers, but it explains a lot of other things too.) This is what normal people who enjoy a nice drive would do.

As anyone who’s whipped around an empty high-school parking lot could tell you, rocking the steering wheel back and forth like Wesley does creates a push-pull swerving sensation that’s much more enjoyable in theory than in practice. If you’re a 17 year old looking for a quick thrill when you’re all out of kratom or whatever, sure knock yourself out. But to drive that way over a significant distance is less fun than just driving straight, not more.

Ben Gazzara sells the nauseating joyride as well as you’d expect from an actor who, prior to Road House, created the role of Brick in Cat in a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams. And indeed we can take Wesley’s glee as entirely sincere, but not because he’s having fun driving in and of itself. He has gone out of his way to make his drive less physically enjoyable, because the thrill of being a gigantic asshole and recklessly endangering the lives of others more than compensates for the loss.

This is the kind of man Brad Wesley is. He can hey-nonny-ding-dong-alang-alang-alang his way back and forth across every inch of asphalt in Jasper and none can say him nay. That’s worth a crick in the neck.

027. Red

January 27, 2019DALTON: Dalton.

RED WEBSTER: Red Webster. How long you gonna be in town?

DALTON: Not very long.

RED WEBSTER: That’s what I said 25 years ago.

DALTON: Really? What happened?

RED WEBSTER: Oh, I got married. To an ugly woman. Don’t ever do that, it just takes the energy right outta ya! She left me though. Found somebody even uglier than she was. That’s life. Who can explain it.

This is a segment of the first conversation Dalton has with Red Webster, auto parts supplier and owner of the closest business establishment to the Double Deuce. When this exchange takes place, these men have known each other for exactly thirty seconds. Their only dialogue up to that point is about which parts of Dalton’s vandalized car need replacing, and whether he should put in a standing order due to the nature of his job or pay as he goes. Compare this interaction to the way Dalton speaks to the staff of the Double Deuce the night he arrives—spartan and only barely polysyllabic. Red, it seems safe to say, is an oversharer.

When Red starts the story of his failed marriage to his ugly wife, however, it’s not clear this is anything more than a take my wife please joke, “It just takes the energy right outta ya” being the punchline. But then he keeps going, in short little bursts that sound like Manic Street Preacher song titles from the Richey Edwards era:

she left me though

foundsomebodyevenuglierthanshewas

that’s life

whocanexplainit

And boy oh boy does it sound like he wants to keep going from there! Credit the naturalistic performance of actor Red West (yep), a former high school chum and entourage member of Elvis Presley’s; it sounds like he’s actually cleaning out his mental closet right in front of us.

Unfortunately the vicissitudes of capitalism demand that Red pause long enough to ring Dalton up. This gives the cooler a chance to reinsert himself into the conversation before Red can continue his bittersweet reminiscence. Seconds later Brad Wesley and his chief goon Jimmy pop in and the moment is gone. Yet I often think of what it might have been like had they never arrived, or had Dalton never piped up. How far down the Red Webster hole could we have fallen?

Oh, I got married. To an ugly woman. Don’t ever do that, it just takes the energy right outta ya! She left me though. Found somebody even uglier than she was. That’s life. Who can explain it. Went to a seminar once. Thought it’d sort me out. Est, they called it. Bee Ess, you ask me. Cost a pretty penny though. Had to sell the old place. Moved in with my stepdad. Hell of a man. Saved my mother from herself, I reckon. Daddy died at Anzio. Stepdad came into the picture a year later, think it was. Car salesman. Figure that’s where I got it from. Bum leg. Died in ’77. Boat accident. Hell of a thing. Seen that boat store cross the street? They’re the ones sold it to ‘im. Nearly went outta business. All that bad press. Settlement put my niece through med school. Brother never forgave me for it. Wanted her to go into the family business. Took over Momma’s apiary after the the cancer took her. Loved his little girl. Figured she’d follow in his footsteps. She had different ideas. People hate different ideas alright. Always do. Crazy ol’ world. Wound up sellin’ the bees anyways. ‘Llergic. Twenty-two years and not a sting. Tripped on a garden hose. Face first, right into the hive stack. Coma. Thought he’d lose the eye. Gotta wear one a’ them patches now. Looks like a pirate. Who’d’a thought. Car salesman, last I heard. Full circle I guess. Shame, though. First-rate dancer. Thought he’d go Broadway. “Red?” he says. “The dance never made nobody’s bread taste better.” Had a point. Always called it that, the dance. Fancy-like. Heard they’re bringin’ that Batman back. From the tee-vee. Gonna be a movie. Darker, they’re sayin’. Thought I’d read me one a’ his funnybooks. See what’s goin’ on. The Batman, they’re callin’ him now. Don’t that beat all. Drove up to St. Louis. Found one a them stores, sells nothin’ but funnybooks. Die-rect Market, they called it. Die-rect to who? Reminds me of that Home Box Office. Gotta be pig ignorant to want a box office in your home. People linin’ up, yellin’ at you when the picture’s sold out. Kids sneakin’ in. Cold at night. Thick glass. Got some good progr’ms though. Boxin’. Seen that Die Hard on there. Helluva film. California. Never been. Don’t know what to make a them Kids in the Hall. You seen ’em? Pythonesque. Nature a’ the format, you ask me. Anxiety a’ influence. Nothin’ for it. Five’ll get you ten that’s why I sell car parts and not the whole thing. Wanted to do things my way. Outta my stepdad’s shadow. They fuck you up, your mom and dad. May not mean to, but they do. Larkin. Poet. English fella. Ain’t half bad. Spent nine months in Cornwall once, ‘fore I met the wife. Thought it’d be educational. Learn them Celtic dialects. Did some fishing. Hated it. Boats. They they are again. Recurrin’ characters, you might say. Who’s the author. There’s the question. Can’t find no answer. Never been what you’d call a religious man. Couldn’t see the percentage in it. Master a’ my own destiny’s how I like it. Funny way a’ sayin’ it’s all my fault. There it is. Still. You blame yourself, stands to reason you can fix it too. Better’n believin’ it’s all random. Agency, causality. Free wlll. Love’s a neurochemical reaction? Over-reaction, in my book. But who’s to say. Could be it’s inexhaustible. Could be one a’ them zero-sum jobs. Give love here, gotta take it away from there. Wife thought so. ‘Bout yanked my heart out, ‘fore I saw the light. Blinded by the ugly I suppose. ‘Less I used to see clear, and it’s heartbreak what done for my way a’ seein’ things. Ain’t that a kick in the ass. Wonder what else I got wrong. Shaped by circumstance. Sum a’ your experiences. Nature, nurture. Either or. Can’t step outside a’ yourself. Didn’t need a seminar to teach me that. Times are I look in the mirror, can’t even recognize m’self. Who’s that old man? Still got all my hair, though. Red as ever. Caught hell in school for it. Carrot top. Tried tellin’ em the name didn’t have nothin’ to do with it. La Rouge. Momma’s maiden name. French Canadian. Way back anyways. Looked into it once. Microfiche. Didn’t get very far. Fine print. Need glasses. It’s like I said: Used to see clear. Just can’t bring m’self to do it. Proud a’ these eyes, always have been. Girls loved ’em. Baby blues, they said. Got me further’n anything else I had goin’ for m’self back then. Still remember that first time. Told Momma I was goin’ to the pictures. She was a picture alright. To a fault. Hair trigger. Over ‘fore it started. Recovered fast though. Kept at it for two hours. Next day neither a’ us was walkin’ right. Mm mm. She was a one. State senator now. Mail her a donation every cycle. Sends a thank you. Neither of us says anything about it. Figure we don’t need to. Said all we needed to say that night. More’n one way to tell someone how you feel. You gotta tell ’em, though. One way or the other. No point to it all otherwise. Connection. Long and the short of it. That’ll be $2.99 for the aerial.

023. Valet

January 23, 2019This man is Chino “Fats” Williams. A character actor with a string of bit parts from the ’70s through the ’90s, he appeared as a character called Fats in four different projects, from Baretta to House Party. In Road House he’s billed as “Derelict,” which coincidentally or not is the same title he receives in Rocky III, the third and final installment of that franchise in which he acted as a downwardly mobile person. It is unclear whether he was playing the same person in all three Rocky movies, and equally unclear if the Derelict from Rocky III is the same Derelict from Road House, and thus if Wade Garrett and Ivan Drago exist in the same cinematic universe. An enterprising mid-tier comics publisher should look into the rights situation, because that is the crossover event of the century right there.

Be that as it may. Dalton knows none of this when he drives up to the New York parking garage where he stores his Mercedes, which he plans to take to Jasper. By now you’ve read enough to know that he always stashes his fancy ride away when he’s working so that angry customers don’t take out their frustrations on it, replacing it with some old beater or other, the way you wear a ratty old t-shirt to do serious housecleaning or what have you. This means that after quitting the Bandstand and agreeing to work the Double Deuce, he has to get rid of his New York jalopy before he can head for Missouri.

He does this by parking in front of the garage and tossing his keys to the above individual, who’s seated comfortably outside the garage entrance. Both confused and irritated, the man says to Dalton, “What do I look like, a valet?”

The answer, frankly, is yes.

He is sitting expectantly in front of a parking-garage entrance in the middle of the night on an otherwise empty street. God knows what else he’d be doing there.

But this is beside the point. The important thing about Chino “Fats” Williams and his Derelict role is the voice with which he says his one line. The best way I can describe it—and I’ve thought about this for years—is that he sounds like if Statler & Waldorf from The Muppet Show gargled with razor blades and then sucked down a bunch of helium. “Elderly frog angry about getting thrown out of a bar for chainsmoking” could work as well. The man has the most memorable voice in the movie, which I remind you also stars Sam Elliott, Terry Funk, Kevin Tighe, Ben Gazzara, and Keith David (kinda). He may or may not look like a valet, but he sounds like no one else on earth.

Anyway, turns out Dalton neither knows nor cares who he is. He tossed the guy his keys because he’s giving him the car. “Keep it, it’s yours,” says the nation’s second-greatest cooler. “Mm?” murmurs the Derelict quizzically. “Mm,” he responds to himself firmly. With a little “Well, alright, if you insist” shrug, he gets up and heads to the car. Apparently he has places to be, though you wouldn’t have known it from the fact that he’s sitting by a parking-garage entrance alone in the middle of the night like…well, you know.

020. Nothing personal

January 20, 2019“I want you to remember that it’s a job. It’s nothing personal.” We’ll be exploring of Dalton’s three simple rules for bouncing my Jasper road house in depth as the year progresses, but this elaboration of Rule Three, “Be nice,” bears scrutiny here in this early stage of the game. If you want to know what Dalton’s about, you need to see how seriously he takes not taking things personally. For now.

On Dalton’s first night on the job—the night of the Giving of the Rules—he makes a lot of enemies. He fires Morgan the bouncer for being a rat-bastard sadist and Pat McGurn the bartender for stealing from the register; both these men are members of the Wesley outfit and will repeatedly attempt to murder Dalton for costing them their jobs at what is, let’s face it, a complete shithole. He fires Steve the bouncer for having sex with teenagers on the job and he fires Judy the waitress (not that anyone ever says her name in the movie, of course) for dealing drugs on the job; neither shows up again but it’s hard to imagine losing their sexually and/or financially lucrative side hustles along with their day jobs sits particularly well with them. He also encounters a man who reacts to being asked to escort his girlfriend off the table she’s dancing on by whipping out a switchblade and threatening to stab a bouncer to death, and uses this man’s face to break a separate table in half before throwing him out; provided he hasn’t suffered a brain injury, my guess is he’s pissed off about it.

So there’s no surprise, and no shortage of suspects either, when Dalton walks outside and sees that his new car has had its windshield shattered, its antenna broken, and all four of its tires slashed.

Dalton saw this coming, of course. As previously mentioned, he makes it a habit to buy a beat-up used car while he’s working, knowing how the people he alienates tend to react. But this isn’t grudging acceptance of a bad situation, the way you might grumble standing on line at the grocery store the night before a big snowstorm. When Dalton sees what’s been done to his car, which will require him to jack and replace all four tires at a minimum before he can even think of addressing the other problems, he simply smiles and shakes his head. He’d shoot the same you-gotta-laugh look if he had a toddler who just covered her hair with peanut butter.

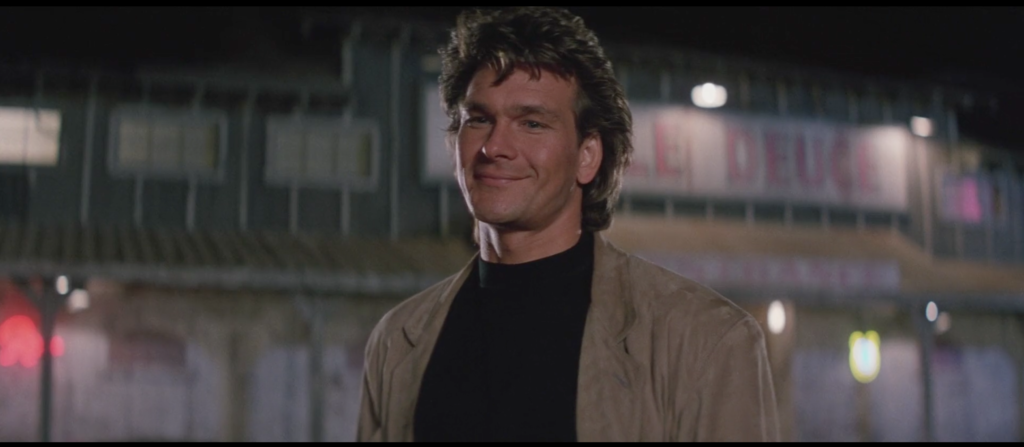

This is the face of a man who has a job, who does the job, and who does not take the job personally. His background in philosophy might help. Same with his study of tai chi. And in general he reverts to “laid back” as a default setting when external stressors are absent. And I mean that literally: When Wesley sends his goons Tinker and O’Connor, who recently tried to murder him and got their clocks cleaned for their troubles, to fetch him for a sit-down, he’s lying on the car that their fellow goons most likely vandalized the way a normal person might relax on a hammock.

But the “it’s a job, it’s nothing personal” thing is crucial to understanding the transformation Jasper, Missouri forces him to undergo. With each scene, you can watch his progress from one end of that spectrum to the other. Just know that this is where he starts.

003. The Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri

January 3, 2019If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig. —Uilliam M. Bricken, Jr.

An English professor of mine used that self-reflexive riddle to illustrate the way Christ’s parables are both medium and message: The second the concept behind the parable clicks, so does the larger point about ethical behavior or spiritual enlightenment.

In his book The Three Christs of Ypsilatnti, psychologist Mark Rokeach recounts an experiment, which he would later apologize for and reject as unethical, in which he placed three men who believed themselves to be Jesus Christ in regular group therapy sessions in hopes that encountering each other would shatter their delusions, to which end he occasionally manipulated them directly by concocting imaginary elements of their collective story himself. The experiment was unsuccessful.

This man is Big “T” of Big “T” Auto Sales, or so it seems safe to assume. We meet him around 17 minutes into the film, as he watches The Patty Duke Show on his office television while preparing to eat his lunch. He then notices our hero, Dalton, checking under the hood of a beat-up old car in the lot. “She’s a runner!” shouts this walrus-looking sonofagun as he strides out to meet Dalton face to face, treating the singular requirement of any used car sale—that the car being sold is capable of movement—like a selling point. Dalton drives a Mercedes when he’s not on the job, but since angry patrons of the bars at which he serves as cooler tend to take their frustrations out on his car after they’re ejected, he replaces it with a cheaply bought beater when he’s got a gig. He takes the car. We never see Big “T” again.

This man does not have a name, not that we’re given to know anyway. We meet him about one minute after we meet Big “T.” This fellow presides over some kind of automobile junkyard Dalton goes to not to purchase a used car, which he could have done here since used cars are visibly on sale in the background, but to stock up on spare tires, since people who are pissed off that he smashed their face through a table because their girlfriend was dancing on another table often slash his tires in revenge. Dalton loads the trunk of his new old car with tires and gives the proprietor a little salute, which the old man returns. We never see this man again.

This man is Red Webster, proprietor of Red’s Auto Parts. We meet him around 33 minutes into the film, after which he becomes a major character. His store is the closest business to the Double Deuce, with which it shares some kind of vast dirt parking lot or road or whatever it is despite being about a football field away. His niece is Dr. Elizabeth Clay, former love interest of Brad Wesley and, soon, current love interest of Dalton. He is Dalton’s primary source of information on the protection racket run by Brad Wesley under the guise of civic improvement. Dalton goes to Red’s store to order a new windshield and buy a new antenna for his car after both were destroyed by angry ex-patrons of the Double Deuce the night before. This is the third scene in which Dalton makes an automobile-related purchase, and the third business establishment at which he does so. The movie is not quite 35 minutes old.

This man is Pete Strodenmire, proprietor of Strodenmire Ford. We meet him around one hour and 24 minutes into the film, at a hastily convened meeting of Jasper business owners, plus Dalton and Elizabeth, to discuss the prior night’s destruction of Red’s Auto Parts in an arson ordered by Brad Wesley. There are seven people at this meeting. Four are Dalton, Elizabeth, Dalton’s nominal boss Tilghman (seen above in the background), and Elizabeth’s uncle Red. The other three, including Strodenmire, are people we’ve never seen before; the two who aren’t Strodenmire have no lines, and we never see them again. The next time we see Strodenmire, Brad Wesley has ordered one of his goons to run over the man’s entire glass-enclosed showroom of new cars with a monster truck, which he does with glee. Strodenmire winds up being one of four men—along with Red, Tilghman, and Dalton’s nominal landlord Emmet—who murder Brad Wesley, the film’s antagonist, with shotguns during the climax. Again, we meet him an hour and a half into a two-hour film that has already included three other car or car-parts salesmen.

This man is Emmet. We meet him about half a minute after we meet the man from whom Dalton purchases tires, when he rents Dalton a barn-loft apartment that must have cost $50,000 dollars to build for $100 a month. He doesn’t sell cars or car parts, but you can see how he and the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri share a similar aesthetic.

Road House is a movie about a road house, that much is true. It’s not a movie about roads, however, nor about what you drive on them. (Much more time is spent showing Dalton buying cars, parking cars, and buying car parts to fix what happens to the cars after they’re parked, than is spent showing anyone actually driving cars.) Thus, the film’s maximalist approach to automotive retailers is striking, and bears contemplation.

Could Dalton’s trips to fully four different stores for his vehicular needs have been consolidated to, say, two, perhaps the ones owned by the two men who wind up saving his life from the character played by Ben Gazzara (John Cassavetes’s Husbands)? Yes.

Would this have been an easy way to establish Strodenmire, who I stress fires a shotgun into the body of the movie’s antagonist and inflicts a mortal wound, before the movie was three quarters of the way finished? Yes.

Would this have made things less confusing to people for whom men whose vibe is best described as “Old Fart” sort of blend together in an indistinguishable blur of ill-fitting work shirts and bold facial-hair decisions? Yes.

Is understanding that Road House has its protagonist make car-related purchases from three different men (two of whom are never seen again), includes a fourth as a main character when he emerges from a nameless scrum of unknowns when the movie is almost over (and who has never been seen before), and casts weird old coots in all four roles (with weird old coots to spare playing other parts)—that is to say, understanding things that makes no sense—key to understanding Road House‘s unique rhythm in all its concussive dreaminess?

If this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.