Posts Tagged ‘road house’

067. Table dancer

March 8, 2019“We don’t cause trouble, we don’t bother nobody.” Few of the barflies whose acquaintance either we or the staff of the Double Deuce have the good and/or mis fortune of meeting adhere to Rick the Ruler’s public proclamation of good behavior as closely as Table Dancer. Played by Sylvia Baker, she’s the character who dances on a table. Here are things that, based on the conduct of other barflies in the film, she could reasonably be expected to do instead:

- Pull a knife and threaten to stab someone at a moment’s notice

- Pull a knife and attempt to stab someone at a moment’s notice

- Pull a knife and actually stab someone at a moment’s notice

- Agree to grope a woman’s breasts for money without actually having the money

- Wallop the shit out of someone who groped a woman’s breasts for money without actually having the money

- Offer her breasts to be groped for money without first doing due diligence

- Have a fistfight on the floor with a sibling

- Propose getting nipple to nipple

- Lob a beer bottle at a blind man’s head because he says he has to urinate

- Laugh like an imbecile

- Drink until incapacitated

- Have sex with an employee in the storeroom

- Be part of a team sent by a local businessman to assassinate a bouncer

- Not wear a shirt

- Purchase and snort cocaine, though somehow not in that order

- Deface the walls with vulgar graffiti

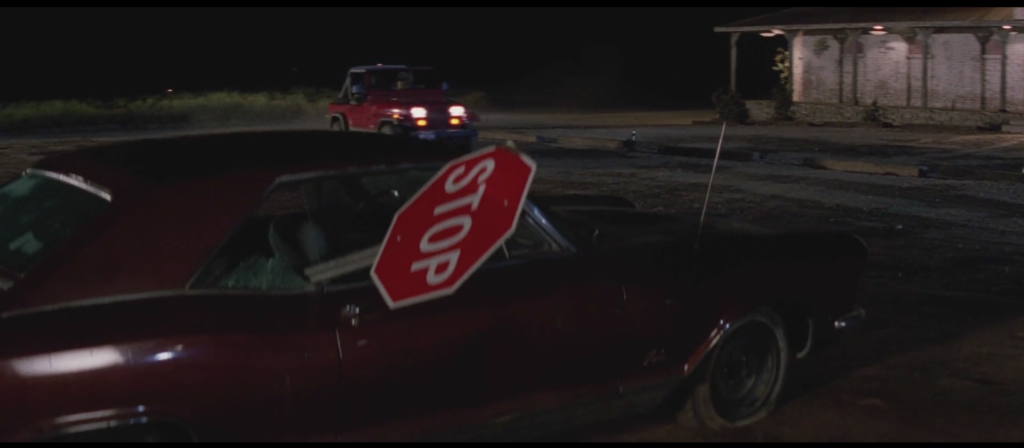

- Locate the vehicle of a bouncer, slash all its tires, break its radio antenna, smash its windshield, and shove an entire stop sign through the window

- Say “dirtball” or “moose-lips”

- Wear a very loud shirt

All Table Dancer wants to do is gyrate spasmodically on a table to the Jeff Healey Band, occasionally lifting her skirt to show that her silver-black bodysuit goes all the way down. It’s her rat-faced boyfriend who decides this is worth committing murder in a room full of witnesses for, not her. She doesn’t even get upset when Dalton rams her boyfriend’s skull through furniture solid and steady enough for her to dance on. She’s just like “Oh! Party’s over I guess” and takes Dalton’s extended hand to climb down off the table, then looks him over like the snack he is as she leaves.

Table Dancer represents the joie de vivre to which the rest of the film’s barflies should aspire. Would Dalton have been so quick to send Hank in to break up the party if this were the worst of the behavior one could expect of the Double Deuce’s clientele? I think not. She falls victim to broken-windows policing more than anything else, like how Giuliani used to shut down all the clubs where black people went to listen to hip-hop to make the city safe for oligarchs, somehow. Am I saying Dalton gentrified and Disneyfied the Double Deuce?

Am I?

066. Frank Tilghman’s fist

March 7, 2019One thing I never noticed before starting this project, one thing I never noticed before tonight in fact, one thing I never noticed despite watching Road House dozens of times over the course of nearly fifteen years, is that when Brad Wesley’s goofiest goons, Tinker and O’Connor, come to the Double Deuce with Wesley’s nephew Pat McGurn to force Frank Tilghman to overrule Dalton’s decision to fire Pat under threat of physical harm and the cessation of liquor shipments to the bar due to Wesley’s control over distribution in the Jasper, Missouri metropolitan area, and Dalton expresses skepticism about the idea, and Pat almost instantly loses his fucking mind and attempts to slice Dalton open with a knife the size of a Little League baseball bat, and Dalton breaks his nose and tosses him through a plate glass window, and O’Connor assaults him and they both go tumbling through the place where the window used to be, and they fall first to a raised dais and then make their way to the main floor below after O’Connor bumrushes him over the railing, and Dalton pounds the crap out of him and eventually beats him unconscious, and doesn’t even bother to deliver a coup de grace, just kind of holds O’Connor up by his jacket for a moment and then drops him to the ground in disgust, and meanwhile Tinker, who during Dalton and O’Connor’s initial fight in Tilghman’s office punched Tilghman in the gut and then sliced Dalton open with his own knife and then punched Dalton in the face before Dalton kicked him in the chest for leverage to thrust himself and O’Connor through the window, meanwhile Tinker he suckerpunches Younger when he rushes through the door to see what’s going on, but then Hank comes in to help and he and Younger incapacitate Tinker and punch him in the gut while holding him still which is the kind of thing villains do but all’s fair in bouncing, and as Jack and Hank and Younger drag the punchdrunk bodies of their enemies through the bar and presumably to the exit, and Dalton is all covered in sweat and blood and getting ready to head out the back door and go seek medical attention, Tilghman, you remember him, Tilghman staggers over to the broken window and makes eye contact with Dalton and raises his right fist in a gesture of triumph and solidarity that’s one of the most ridiculously obsequious things Tilghman does in the whole movie, which in the parlance of our times puts it in the running for most ridiculously obsequious thing worldwide, I mean Tilghman contributed nothing to the fight, he just got winded by Tinker until he was rescued by the other bouncers, but there he is, small business owner, vicariously victorious in his non-worker role, and Dalton gazes into the fist of Frank Tilghman, as he raises that five-sided fistagon, as the bodies get dragged away.

065. “He killed a guy once. Ripped his throat right out.”

March 6, 2019When Frank Tilghman traveled to New York (City?) to hire the (second) best damn cooler in the business and also cast humorous aspersions on the size of his penis, we in the audience pretty much had to take his word for it. Dalton has great hair, a great body, a cool as ice demeanor, the ability to dupe Knife Nerds into leaving a bar of their own volition, and the stomach to stitch up his own knife wounds, yes. But actual bouncing? No evidence of that just yet, much less enough to decide that this lion-maned man is a one-man army in a throwdown.

Conveying just what Dalton is capable of in the clutch (literally) falls to Hank, the Double Deuce’s resident Dalton fanboy. When Dalton first arrives and word of his identity gets around—he tells Carrie Ann and Pat McGurn overhears and thus the legend is spread—the bar’s staff are all aflutter, some with excitement, some with skepticism, some with…whatever emotion covers “shit, I’m not going to be able to steal from the cash register/beat up patrons at random so easily anymore.” Hank is on the excitement end of the spectrum.

“He killed a guy once,” Hank tells his fellow bouncer Horny Steve as they lounge against a wooden post while wearing what would, if combined, amount to nearly one whole shirt. Hank shoots his left arm forward across their bodies, then pulls it back hard, raking his clawed fingers against the air just in front of Steve’s neck. “Ripped his throat right out,” he explains. He sounds like he’s talking about Regina George.

Our man Steven is unconvinced. “Bullshit,” he replies, only he pronounces it in that great movie-hardass way: “Bull shit,” two words, like the t-shirt the kid wears in The Jerk. And for all we know, Steve has the right of it. The way people have carried on about Dalton in this movie so far, there’s no telling what he’s actually capable of on the one hand, and how much his reputation has been exaggerated by the awestruck barfolk of the world. After all, Carrie Ann the extremely cool waitress recognizes his name instantly and reacts like she’s just realized she’s been making small talk with INXS’s Michael Hutchence. People are bowled over by this dude.

Also, and I think this is crucial to understanding a lot of what goes down in the first act of the film, nearly everyone we meet is very stupid. Dalton’s not and Tilghman’s not, that much is clear. But by the time the film hits the 15-minute mark, a grand total of nine words longer than two syllalbes, and zero words longer than three, have been uttered; of those nine, one is “peckerhead” and another is “attitudes.” It’s not difficult to imagine convincing Hank here that Dalton is bulletproof.

But even an extremely dumb clock tells the right time twice a day.

064. I Thought You’d Be Bigger Vol. 1: Tilghman

March 5, 2019At the end of their first encounter Frank Tilghman tells Dalton “I thought you’d be bigger.” This is Road House‘s primary recurring joke; you’ll hear it two more times from two other people. It’s probably swiped from everyone telling Snake Plissken “I thought you were dead” in Escape from New York, for what it’s worth. It’s a groaner, and it’s endearing in its groanerness over time.

It is also a weird thing to say to someone you just met. It’s a weird thing to say even if they’re a person whose job is usually associated with being of a certain size. Imagine meeting a professional wrestler or basketball player and saying that: You can picture the mechanical smile and hear the canned response already, right? Because chances are it’s not the first time the person in the job usually performed by a bigger person has been made aware that they are, comparatively speaking, smaller. It’s more likely that they’ve thought about this for literally decades, like since they were in first grade, than that this charming bit of banter will catch them delightfully unawares.

Frank Tilghman is a weird guy, though, whether by design or by Kevin Tighe’s inability to play him any other way. (A reader I’ve since argued with because I think it’s more likely Steven Spielberg has cinema’s best interests at heart than Netflix does suggested he auditioned for the Brad Wesley part, got Tilghman instead, and simply decided to play the role as Brad Wesley anyway, and it’s a damn good theory.) If you could dress a leer up in a bolo tie, that’s Frank Tilghman. He looks like a police sketch based solely on an eyewitness saying “He was some kind of pervert.” If you can watch him during the opening of this movie and not assume he’s the villain of the piece, I think that constitutes a Turing test failure.

Nevertheless he is one of the good guys, he has no ill intent toward Dalton, at no point does he do anything to antagonize or undermine or bamboozle or even overtax Dalton during his employment at the Double Deuce. This only makes “I thought you’d be bigger” even weirder.

Yet the way he says it is the weirdest thing of all, way more than the mere fact of saying it. He’s closes a deal bringing the best young cooler in the nation into the fold for a cool mid-six-figure salary, with no set start date. He does this while watching Dalton a) stitch himself up from a knife wound Tilghman also watched him incur minutes earlier, and b) summarily quit his current job while treating the owner of the bar he’d worked in like dogshit. And what does he do on his way out the door but pause, flash that unmarked-van grin, and say “You know, I thought you’d be…bigger.” The ellipsis represents a pause so pregnant with implication and innuendo its water is breaking, and the emphasis on bigger is definitely in the original, and did I mention he literally looks Dalton’s shirtless body up and down as he says this?

Now then. Do we have reason to believe Tilghman lusts after Dalton? Yes: Dalton is reason enough for anyone to lust after Dalton. Do we have reason beyond that? Yes: My theory that he and Pat McGurn were at one time involved romantically for one thing, or my other theory that the mysterious fortune he’s suddenly come into that allows him to renovate the Double Deuce and hire Dalton to keep the place secure came from an old rich widow he seduced as a closeted gigolo, persuaded to change her will to make him her sole beneficiary, and then tossed over the railing of a cruise ship, like the “Not great, Bob!” storyline from Mad Men, would (if true) indicate he is attracted to men and also makes destructive decisions in that regard. Are we intended to read his “I thought you’d be…bigger” as both a come-on and a sexualized dick joke? Yes: Our eyes and ears are not lying to us.

Do we need to respond with the kind of gross shitty gay-panic laffs we might have expected from movies and audiences alike for decades prior to this film’s release and at least a couple decades after it? No! The proper way to respond is this. First, to paraphrase RiffTrax’s Mike Nelson, the question of whether Kevin Tighe is trying to bed down Patrick Swayze, or the character equivalents of same, is a fascinating one on its face. It’s like when you learn Kate Beckinsale has a kid with Michael Sheen, which many people just learned when they also learned Kate Beckinsale is fucking Pete Davidson, the Saturday Night Live lotto winner who was previously fucking Ariana Grade. “A lot going on here,” I believe is your American expression, yes?

Second, and more importantly, this is a workplace safety issue, because Frank Tilghman absolutely is sexually harassing his new employee here before his first day on the job! Frank Tilghman may be on the side of the angels where the larger war for the soul of Jasper, Missouri is concerned, but he is without question an awful boss. Remember that before Dalton, Tilghman’s hires (that we know of) include two Brad Wesley goons and an extremely surly and obvious coke dealer and a guy who allows teenagers into the bar so he can have sex with them. The fish rots from the head.

Seen in this light, “I thought you’d be…bigger” becomes more than a come-on or a dick joke. It’s a cry for help. Frank Tilghman knows the magnitude of the task ahead of him—not cleaning up the Double Deuce, that’s just a metaphor, but cleaning up Augean stables of his very soul. To Tilghman, that is Dalton’s true task. Beneath the clumsy curiosity about his new hire’s penis lies the real question: Is he man enough to make me whole?

063. Patrick Swayze Beating the Shit out of John Doe from X

March 4, 2019Road House is a film in which Patrick Swayze beats the shit out of John Doe from X.

It’s simple, really. Sister-son Pat McGurn returns to his former place of employment with his uncle’s most useless enforcers O’Connor and Tinker in tow in order to force proprietor Frank Tilghman to reverse the decision of the bar’s new cooler Dalton and reinstate him to his position of bartender. Dalton takes very mild issue with the plan. Pat whine-gloats like a petulant child who thinks their parents are gonna punish their little brother and not them, then produces a knife the size of a machete and proceeds to simultaneously slash at and gay-panic taunt Dalton. Dalton punches his nose in. While he holds his hands to his broken face and howls in pain, Dalton spin-kicks him through a plate-glass window. He remains incapacitated for the duration of the fight that ensues, after which he is bodily carried out of the bar.

Concerned that Pat McGurn didn’t receive enough punishment? I’ve got you. First it’s important to note that by the end of the film Dalton will murder Pat McGurn, using the body of a dying goon to block Pat’s shotgun blast, then withdrawing the knife he’d inserted into the now dead goon’s gut and throwing it into Pat’s chest, causing him to misfire one last time and then plummet from a second-story landing to the ground below. Second you’ll notice from those screenshots that Pat’s nose was already bleeding before Dalton’s punch connected; you can call this slapdash continuity if you want, but I prefer to believe that either his body anticipated the damage that was about to be done to it and started hemorrhaging spontaneously, or that Dalton caused him to bleed without touching him by sheer force of chi. Or both! I’m not picky.

But here’s the bottom line, friends: Road House is a film in which Patrick Swayze beats the shit out of John Doe from X.

Pain Don’t Hurt: The Patreon

March 4, 2019The name…is Sean T. Collins. I’m a writer and critic who’s appeared in The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, Vulture, Decider, Grantland, the AV Club, and more. I’m also the co-founder (with Stefan Sasse) of The Boiled Leather Audio Hour, a podcast about Game of Thrones & A Song of Ice and Fire, and the co-editor (with Julia Gfrörer) of Mirror Mirror II, an anthology of horror/erotic/gothic comics and art published by 2dcloud. I’m The Original Bad Boy of TV Criticism. I gave this nickname to myself as a joke but it stuck so it counts.

Also, I love Road House, the 1989 Patrick Swayze action movie. Road House is the story of Dalton, a famous bouncer whose quest to free a small town from the iron fist of the guy who is on the verge of opening the area’s first JC Penney will lead directly to the deaths of over half a dozen men. I love Road House so much in fact that in late 2018 I decided I would write an essay about Road House every single day for an entire year, that year being 2019—on top of the TV recaps, album reviews, film and television recommendations, and broader essays and deep dives I write for a living.

In the words of Road House, I’d like to make a better life for myself.

By subscribing to my new Patreon you’ll make Pain Don’t Hurt a paying concern. If you’re a fan of my Road House stuff this sells itself. But the beauty of getting paid to write about any one thing is that it makes it possible to write even more about other things. If you’ve ever enjoyed anything I’ve written, subscribing here is the best way to see more of it—both through tiered rewards that give you access to bonus stuff and simply by helping my family and I stay afloat so I can do more of the writing I love. (I love to write even more than I love Road House, though it’s obviously close.)

Friends, it’s time to be nice. Join the Jasper Improvement Society today! Thank you for your support!

062. Sears

March 3, 2019Some lines punch above their weight class. You know what I mean? You can feel them searing their way into your brain and then lodging there, as close to permanently as anything can in a world that feels like a blow to the head every day, despite them not being important or funny or even good. One of those quote-tweet audience-response twitter threads went around recently to this effect, asking what obscure movie lines have become a part of your everyday vocabulary or thought patterns. My personal choice, besides the obvious, is a woman at a dinner party in Hellraiser squawking “Doctors!” in this over-the-top, probably dubbed-to-replace-an-English-accent what a world way, and her husband responding with a “That’s right, honey” so patronizing it makes your eyes water.

I can currently feel this happening with poor Jack, that’s him on the right above, trying and failing to prevent his fellow bouncer Horny Steve from allowing two young women below the legal drinking age from entering the Double Deuce with IDs so woefully inadequate to the task of age verification that they aren’t even fake. “This is a Sears credit card” he tells Steve, who’s in the middle of greeting his lady friends Beverly and Agnes and could not possibly care less. I feel it searing, and I swear there was no pun intended. I feel it becoming the way I react to any frustratingly bogus situation or nonsensical explanation, like the pet-shop clerk who tells Parker Posey “This is least like a bee of the ones that we have here” when she’s desperately searching for a replacement Busy Bee for her dog in Best in Show, or Kramer and company shouting “These pretzels are making me thirsty!” in Seinfeld. Car says it’s out of gas even though it previously said there were forty miles left in the tank? This is a Sears credit card! Laptop won’t remember a password I’ve entered in a million times? This is a Sears credit card! Politics??? This is a Sears credit card! I will never see the softer side of Sears again. I accept this.

061. The Third Rule, Verse 2

March 2, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, again, is the third.

3. Be nice. (continued)

When first we assayed the Third Rule, I said the following:

It is the shortest rule, and it requires the most explanation. It is the least practically minded rule, and it is illustrated with the most practical applications. It is a rule about being kind to others, on the surface at least, and it is the rule greeted—and at times delivered—with the most open incredulity, even hostility.

When Dalton tells the assembled staff of the Double Deuce to be nice, it is Jack the bouncer who, whether in spite or because of being Dalton’s best student, opens the door for doubt. “Come on,” he says, gently but with unmistakable disbelief. He’s trying to ask his new sensei “Are you out of your mind?” in the politest possible way.

Now comes the yin-yang instructional configuration that should be familiar to us as central to the Giving of the Rules. Dalton leans forward and tells Jack “If somebody gets in your face and calls you a cocksucker, I want you to be nice.” Jack responds with a skeptical “Ohkayy”—and, though he knows it not, passes the test Dalton has just given him in so doing. Dalton got in his face and called him a cocksucker, and he was nice. It takes the doing of the thing to see that it can be done and learn how to do it. If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.

(to be continued)

060. “Hey, you’re paid to play—play!”

March 1, 2019Here’s a singularly unpleasant chain of events. Wrapping up his latest white-blues scorcher, Cody, the lead singer of the Jeff Healey Band, announces he and the band will be taking a brief break because, quoting here, “gotta drain the main vein.” I go back and forth on this. Not on whether it’s an awful thing to say, because it is; even a film this aggressively stupid that line lands on first-timers like punch in the nose. But in a way I think it’s gutsy to introduce a character by having him use a grotesque euphemism for using his penis to urinate in his first spoken lines of dialogue. And at least it rhymes, unlike “I heard you got balls big enough to come in a dump truck” or “Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick” or “I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick” and probably a few other phallocentric howlers I’m forgetting. That’s no doubt one of his proficiencies as a bard.

Then this man—you remember this man, he’s Heckler, played by Charles Hawke, and he’s a non-voting observer nation in The Agreement—then this man says something less unpleasant to read but vastly worse to hear. “Hey, you’re paid to play—play!” he screech-slurs in a hideous Noo Yawk accent that’s practically Piscopovian in its cartoonishness. Rendered phonetically s it’s more like “HAY YA PAID TA PLAY PLAY!“, its dulcet outer-borough tones more than a bit anomalous in a film whose language is listed as “Yokel” on the cassette box.

With that he throws a bottle of beer, still half-full, at the chickenwire fencing surrounding the Double Deuce’s stage. The guy’s got a real cannon of a right hand apparently, because it shatters into a million pieces with a sound you might associate with dinner scenes in which a guest says something so shocking that the hostess drops her plate.

The reaction of Jeff Healey Band frontman Cody is inscrutable. Judging from the way he reaches his hand to his bottom lip and growls “Fuck!” I think we’re to take it that a piece of glass made it through the mesh and cut him on the face, but two data points would seem to dispute this. First, he’s not visibly injured in his ensuing conversation with Dalton, and Road House is pretty fastidious about making sure people bleed properly. Second and more puzzling is his reaction in the moment: He simultaneously snaps his head back and flops forward, as if completely poleaxed. Again, the bottle hit the chickenwire, not him.

The logical explanation is that Cody is a sort of “earth spirit” or personification of the Double Deuce, serving a function similar to that of Tom Bombadil vis a vis Middle-earth in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, though with the additional characteristic of suffering when the place through which his existence is defined suffers. As an elemental of this sort he can be expected to react strongly to damage he senses through his metaneural network. However, at no other point does Cody display this type of symbiosis with the Double Deuce, not even in the cataclysmic brawl that takes place just a few minutes later, so this theory too needs reexamination.

So we turn back to the other participant in this pas de deux, Heckler. Heckler, who lurks on the margins of The Agreement, the dissolution of which nearly destroys the bar. Heckler, who throws a bottle with sufficient force to break it to pieces on a fence. Heckler, who can wound this troubadour with pure mental animus. It seems safe to conclude that he is a black magician, or even a demonic entity himself, warping the world around him with his corrosively evil presence. Witnessing the Coming of Dalton, he wisely chooses to depart rather than test his strength against a servant of the Secret Fire, leaving more ambitious or more foolhardy members of his infernal cohort to fight in his stead. Who knows how many such creatures Dalton has banished by his mere presence.

059. Men in Black

February 28, 2019When I wrote about Wade Garrett yesterday, I remembered something about his black t-shirt: He’s not the only cooler in the movie to wear one. The other of course is Dalton—but it’s not like he wears it all the time. The movie shows us he’s molded in Wade’s by deploying black in his wardrobe on three key occasions.

Attentive readers of Pain Don’t Hurt will have guessed the first by now: The Giving of the Rules. This takes place prior to Wade’s introduction, directly linking the older man’s debut to the establishment of his acolyte’s doctrine.

The second is the fight that takes place the night he and Doc have their first date, which is also the first time we see him on the job after we meet Wade. This reinforces the sense of succession while also tying Dalton’s romantic flourishing to the older man’s tutelage.

The third is his impromptu breakfast summit with Brad Wesley, during which Wesley brings up his checkered past and offers to hire him away from the Double Deuce. It’s not a t-shirt here but a collared shirt, as befits this more formal occasion. But the dialogue makes direct reference to an event in Dalton’s past that Wade will also bring up (while wearing a collared black shirt himself) later in the movie, and shows Dalton standing up to an asshole in a way that would do his mentor proud—even if he’d likely suggest getting out of Dodge afterwards.

Clothes make the man. Clothes mate the men.

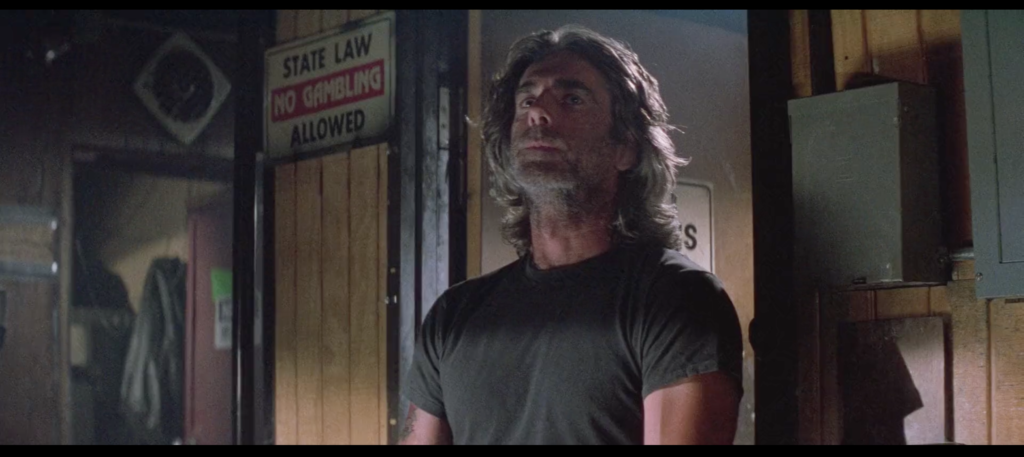

058. The Sentry

February 27, 2019The shadow lies upon Wade Garrett when first we see him. He stands ramrod straight, stiff lipped, chin up, eyes alert. He rocks back and forth from the intensity of the vigilance thrumming in every sinew and synapse. To his right is a sign of prohibition. To his left, a box controlling the generative energy of the bar itself. Behind him, a doorway, barred by his very body. His hair is grey with the knowledge and peril of the long years, and his raiment is black. Wade Garrett knows the gate. Wade Garrett is the gate. Wade Garrett is the key and guardian of the gate.

At that very moment, here’s what he’s looking at.

Not without professional cause, mind you. Within seconds, a horned-up Marine yells “CHARGE!” and rushes the stage, and Wade must rush into action. He sits the jarhead’s ass back down and defuses the situation with a quip about Rambo and saving the world from the Commies that shows Dalton is not the only cooler for whom Be Nice is a cardinal rule. But his protégé, strong though his game may be, could never match the sly grin Wade flashes at the dancer he rescued, who smiles and winks appreciatively in return. Condoms have been lab-tested with less.

What can we learn of the Way of Wade Garrett from this sequence? Most obviously, the integrity of the Wet T-Shirt G-String CONTEST every NITE! would rightfully be called into question but for his presence. We see that humor, even irony, feature prominently in his bouncing arsenal. We see him through the eyes of a dozen drunk, erection-toting members of the United States Marine Corps, who view him as likeable enough, formidable enough, or most likely both to allow him to lay hands on one of their number and walk away unscathed (and bowlegged). He is himself horny, and hairy, but not handsy. He’s quick to action, but not eager for it; not for him is Dalton’s remonstrance to Morgan about not having “the right temperament for the trade.”

And from that first look at him, standing silent sentry in the half light, we see that he harbors within him a darkness—one that does not belie the revelry with which he surrounds himself and the merry manner in which he polices it, but which informs and complements it. He is only at ease because he knows all there is in the world to worry about. Those things have worried at him, and he has held them at bay. For now, anyway. For now.

057. “It’s my way or the highway.”

February 26, 2019Dalton, during the prologue of The Giving of the Rules: “It’s my way or the highway.”

The highway:

Show me the lie.

Whether by accident or design—who can say? alright I can say, it’s by accident—there is no aphorism, no catchphrase, no idiomatic expression, no imbecilic threat or come-on or dick joke in the entirety of this film that does not bear close, even literal, reading. This is what I want to impress upon you more than anything else. This is what inspired this project: the sense that in the 15 years I’ve been watching this movie I haven’t touched bottom any more than you might during a swim in the middle of the ocean. Road House is a journey of discovery, a highway if you will, and the higher you fly the deeper you go the deeper you go the higher you fly so come on come on come on it’s such a joy.

056. Gi

February 25, 2019Several martial-arts disciplines utilize the gi, a simple uniform developed over time with the physical and strategic demands of each particular discipline (judo, karate, whatever) in mind. Dalton, who in another life would have made a hell of a mixed martial arts fighter, likes to wear his out on the town sometimes. It’s the only outfit we see him in not once but twice: first on the day he takes a trip to the auto parts store and discovers that Red Webster is getting shaken down by Brad Wesley and his goons, and second on the day of his final mad battle against the Wesleyans. Dalton is wearing a gi when Red springs the original colloquialism “Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?” on him in lieu of the traditional “Is the Pope Catholic?”, and again when he approaches his niece Dr. Elizabeth Clay in the middle of examining the x-ray results for her latest trauma patient and/or colonoscopy recipient to beg her to skip town with him so they can avoid the wrath of her insane Fotomat-owning ex-husband. But I assure you that in neither case did he slip this clean white garment on in anticipation of seeing action. It’s simply the film’s way of communicating that the Dalton Path stretches from East to West. In many ways it’s an equivalent signifier to stretching with a lit cigarette in his mouth, or waking up hung over from a late-night binge-read, or receiving a philosophy degree from NYU for studying “man’s search for faith, that sorta shit” prior to becoming a professional ass-kicker, or asking for a king’s ransom as a salary but living in a place that costs $100 a month and driving a car chosen specifically because it’ll function basically the same if it gets half-destroyed by angry drunks whose noses he’s broken, or doing tai chi by the water in between tours of every greasy spoon and dive bar in town. He is a human mixed martial art. Might as well dress the part.

055. Rise and shine

February 24, 2019After a long night of breaking tables with people’s faces, firing bouncers for fucking teenagers in the storeroom, making Frank Tilghman fire Brad Wesley’s nephew (and I think it’s safe to say his own lover) Pat McGurn, and reading Jim Harrison novels while Wesley and his goons have a topless pool party across the water, Dalton likes to get out of bed hungover without drinking a drop the night before and fully nude in front of his co-worker Carrie Ann, light a cigarette before he finishes buttoning the fly of his jeans, and do some light stretches without even taking the lit cig out of his mouth as she presents him with coffee and a jelly donut or a danish or something. That’s just who he is. That’s just how he (jelly)rolls. The whole little morning ritual we see when Carrie Ann pays him her erotically charged visit is a delight precisely because of the incoherent portrait it paints of this man. He’s constantly smoking even when he’s exercising but he turns up his nose at junk food. His entire method of bouncing depends upon everyone reading everyone else for the slightest cues and clues but he walks around bareassed in front of a woman over whom he has hiring and firing authority, who’s there delivering him food out of the goodness of her own heart. He’s a huge nerd who was up all night reading a book, to the point where he frowns upon some relatively wholesome sex-comedy shenanigans over at Wesley’s place, but when he wakes up it’s like he’s coming off a three-day bender. If you sat and tried to depict the contradictory demands of ideal masculinity—stoic yet vulnerable, wise yet monosyllabic, sexy yet oblivious to his own sexiness, abusing the body he treats as a temple—I don’t know if you could come up with a better illustration than a shirtless Dalton doing his morning stretches while smoking like Dan Aykroyd in Ghostbusters while wearing pants he hasn’t quite finished putting on.

054. The Ballad of Pat & Tilghman

February 23, 2019Standing in the bar down in Jasper

Sweeping up the eyeballs for thrills

My bartender’s Pat

Hey, at least I have that

Until when Dalton said he’s skimming the till

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Finally found myself with some money

Thought I’d fix the place up just right

Dalton helped me to learn

That my man Pat McGurn

Costs me about a hundred-fifty a night

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Pat McGurn’s the son of Brad’s only sister

Canning him’ll take me some nerve

I may own the bar

That only takes me so far

Cuz Mr. Wesley owns the liquor I serve

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Wesley takes my money almost every day

“Jasper Improvement Society”

It’s his town he said

Oh boy when he’s dead

The killers will be four men who are old (Tink)

“Take the train, consider it severance”

Pat looks at me raising his brow

Incredulous Pat:

“I didn’t hear you say that”

I stammer “Well, I’m sayin’ it now”

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Pat McGurn’s my headcanon lover

Firing him makes me start to pout

His voice is a purr

When he asks “are you sure”

Takes all I have to whisper “get out”

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

053. Why We Fight

February 22, 2019“This has been, without question, one of the worst weeks of my life, but one man offers succor.” I tweeted this with the above picture a few minutes ago, as I sat down to write today’s Road House essay. I knew exactly what I was going to write about, too. I knew the scene, knew the moment, knew the angle, knew how to flesh it out. It’s one of the ideas that made me want to start this project in the first place. So I’ll get to it, probably soon, and I’ll enjoy it and hopefully you’ll enjoy it as well. But wasn’t until I opened up WordPress in a new tab that I realized the thing I posted on twitter before writing today’s Road House essay is today’s Road House essay.

I’m not going to talk about the week I’ve had, or why it’s been so bad, bad enough that as I type this I am home alone with my stepson instead of out with my partner and our friends because we were supposed to go to an all-sad-songs karaoke party together and I am too sad for Sad Song Karaoke. It’s not really my story to tell anyway. I’ll tell you what is, though: Road House. I don’t think I ever fully understood the concept of “comfort viewing” until Road House came into my life. I don’t think there’s any other film like Road House out there. Viewed communally, which is how I watched it the first time, it’s joy, an invitation to participate in the kind of drunken cinematic mental and verbal horseplay that always makes me think of Ozzy Osbourne saying “eat shit and bark at the moon.” It’s a bark at the moon movie. Viewed in a more intimate setting, with just one or two people who’ve never seen it before, it’s the closest thing to taking a child to an amusement park and seeing a world of delight open up before their eyes, seeing it through their eyes, that I’ve ever found this side taking my daughter to Coney Island for the first time. I have yet to screen this movie for any first-timer who didn’t fall in love with it immediately. Viewed with the person I love it feels like a comfortable couch, a long conversation punctuated by bursts of laughter, the easy romantic camaraderie of talking lightly while getting dressed after sex, a car ride soundtracked by songs we both adore, a hit of Gorilla Glue and a sip of Noah’s Mill, a shared secret, a private joke, a glance that means something to us and no one else. Everyone has these things, but no one has our things; that’s how Road House works. Returned to in isolation day after day, night after night, it has proven to be an inexhaustible source of pleasure and inspiration. This dumbass brilliant movie about a famous bouncer’s duel to the death with an unhinged 7-Eleven franchisee and his army of hapless meatheads for the soul of a town populated exclusively by beautiful blonde women, howling yahoos, and the living embodiments of old man smell is a case study in the rewards of close reading, the powers and boundaries of genre and style, the maxim held close to my heart that the energy of every character in any story can be kinetic rather than potential. At the heart of it all is Dalton, warrior, philosopher, guru, hero, lover, killer, smoker, fighter, fatherless son, living breathing erasure of class distinctions, poet of one-liners and vulgarities, preternaturally calm, childishly petulant, soul of a Blake and body of a Baryshnikov in a world that has made him a gladiator, a prophet and a pusher, partly truth partly fiction, a walking contradiction, played by a beautiful man who once said of the cancer that would go on to kill him “I’m in great condition. I’m a cowboy. I’m a dancer. I’ll beat this.” Every punch in the face, every grotesque insult, every dumb joke, every inexplicable line reading, every grin on Ben Gazzara’s face, every sauntering step Sam Elliott takes, every white-blues song on the soundtrack, every remarkable mutant in the cast, every glimpse of Dalton’s face and hair and chest and ass and credo feels to me to have sprung from the heart of the man that said those words—the cowboy and the dancer who raged against the dying of the light. This has been, without question, one of the worst weeks of my life, but one man offers succor.

052. Boot knife gleam

February 21, 2019

They added a gleam effect to the knife in the boot on the leg of the goon who tries to high-kick Dalton in the head with his knife-mounted boot. Just in case, you know. Even with the closeup—an eyeline match cut from Dalton and his Padawan learner Jack to the boot and then back again (Dalton: “Right boot.” [pause for boot] Jack: “Got it.”)—the audience could have missed it, primarily because even for the kinds of people who might want to watch Road House boot-mounted knives are not the kind of thing you’re trained to spot in the wild. Can’t be too careful, really.

No, really. Let’s review. Never underestimate your opponent. The opponent here is the audience’s inability to recognize a knife sticking out of a Knife Nerd’s shitkicker. Expect the unexpected. You wouldn’t expect someone to miss the knife when it’s one of three things on screen, the other two being the boot and the jeans covering the leg part of the boot, would you? Take it outside. Step beyond the boundaries of yourself and see things through the eyes of others. Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary. The trouble here started when Brad Wesley, outside the bar, ordered this man to go inside for the express purpose of necessitating violence. Be nice. Dalton’s simply points out the location of the weapon to Jack rather than raising holy hell, a first move echoed when he amasses his bouncers, approaches the boot knife goon with a smile, and simply says the bar is closed. Until it’s time to not be nice. The arrival of the boot knife is the big hand reaching Not Nice O’Clock.

That gleam is not just the light reflected off some jackass’s dopey weapon. It’s Dalton’s bouncer-sense made visible.

051. Tableau III (Nipple to Nipple)

February 20, 2019Here in the Double Deuce, after Dalton’s arrival, prior to The Agreement and the subsequent bar-destroying brawl, things are proceeding as one assumes they always proceed. Denise, Jasper’s sole indication that there is a non-Jasper culture out there to which one can aspire, glides up to the bar to ask Pat McGurn (John Doe, cofounder of X, lest we forget) for a “vodka rocks.” Enter the Barfly, and this is actually how he’s credited, “Barfly,” played by Frank Noon. In a film teeming with barflies he is selected as the representative specimen. This absolute slob, I mean maybe the most gormless motherfucker in the whole film, this asshole sidles up to her and says “Hey, Vodka Rocks, what do you say you and me get nipple to nipple.” I hesitate to call this pickup line a euphemism, because it’s actually much more vulgar than describing the sex act outright. Getting nipple to nipple is a phrase that can only make one feel bad about having sex, or wanting to have sex, or being capable of having sex, or being part of a species that propagates itself by having sex. It embarrasses me anew every time I hear it. Goof coming out of his well armed with his quip to slutshame mankind. Point is it’s not happening for this turkey. Denise looks down in contempt, unconsciously mirroring the way Dalton, whose hair is only slightly less magnificent than hers, looks down in disapproval. Then she looks up and, this being Road House, shoots the guy down in the strangest possible way. “I can do that without you,” she says, before turning away and giving Dalton an appreciative once-over (more like a thrice-over actually, she is hot to trot for our hero) in the process. The reasonable interpretation of this rejoinder is that Denise can somehow aim her breasts at one another so that her nipples can touch, a pincer movement if you will. I choose to believe she thought fast and decided to shoot this goofy down by saying something even weirder than he did. Either way, and I hope you’re sitting down for this, he does not take rejection well. See Morgan back there? He’d been leaning on the bar in the background unseen until the dirtball mooselipped chickendick made a pass at Denise. (Do people make passes at other people anymore? When I was a kid Three’s Company and The Golden Girls had me believing that’s all anyone did as an adult. “He made a pass at me” is something I’ve never heard a human being say outside of a multi-camera sitcom. Anyway) The moment after “nipple to nipple” dribbles out of his mouth, Morgan pops into the frame from behind, like a fucking jack-in-the-box. It’s one of my favorite little moments of abject stupidity in the movie. On his worst day in the ring, Terry Funk couldn’t oversell a bump half as hard as he oversells Morgan overhearing someone hit on his secret boss’s girlfriend and getting mad about it. Of course Morgan is always mad. He’s an orneriness elemental. And he puts it to good use when Mr. Nipple angrily grabs Denise by the shoulder. Morgan grabs him by the shoulder, punches him in the gut, and tosses him into a table full of patrons, spilling him and them and the table and the drinks on it and several bystanders to the ground in the process. Why this doesn’t lead to an apocalyptic bar-wide battle royale is beyond me given that The Agreement ends in a nearly identical fashion, but at the very least it gives Dalton, serene and detached, an eyefull of Morgan’s modus operandi. This is clearly a bouncer who will need to be bounced. So! Beautiful, slightly weird woman. Ugly, very weird man. Angry, very angry bouncer. Knocked-over tables. Knocked-over patrons. Pat McGurn. The malign influence of Brad Wesley behind it all. Dalton has just gotten nipple to nipple with the Double Deuce. It’s not pretty.

050. The Third Rule

February 19, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This is the third.

3. Be nice.

The three simple rules for bouncing my Jasper road house all contain and account for their own direct contradiction. More than that, they depend on the aspirant’s ability to formulate that contradiction to be fully understood. Thus “Never underestimate your opponent; expect the unexpected” conveys both that chance will always break in the enemy’s favor and that a true brother bouncer—the unmentioned ally in a rule nominally covering the adversary—leaves nothing to chance at all. “Take it outside; never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary” is as much about one’s headspace as it is about one’s physical space, such that participation in a fight that takes place within the building is a requisite condition for obeying the rule in the first place. Even Dalton’s prefatory statement “All you have to do is follow three simple rules” is best thought of through the formulation of the philosopher Linda Richman: They are neither three nor simple nor rules nor followed.

So. The Third Rule. It is the shortest rule, and it requires the most explanation. It is the least practically minded rule, and it is illustrated with the most practical applications. It is a rule about being kind to others, on the surface at least, and it is the rule greeted—and at times delivered—with the most open incredulity, even hostility.

All this is necessary. One must see the complicated clockwork mechanism behind the simplest maxim. One must learn that on the Dalton Path, all philosophy is applied philosophy. One must be goaded into anger to understand the nature and value of its opposite. These things the Third Rule anticipates, mandates, births into being. This simplest of the three simple rules is alone in meriting a fuller and more complex reformulation from the Giver of the Rules, a new testament to unlock the old. It is the Great Commandment. It is not come to destroy, but to fulfil.

3. Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.

to be continued

049. Jimmy, or The Laugh

February 18, 2019It’s not all fun and games. No, it’s not all fun and games. We joke here at Pain Don’t Hurt, we laugh here, because Road House is a fun and often (nearly always) funny movie. But the Dalton Path leads inexorably toward darker days and nights.

This is Jimmy, Brad Wesley’s right-hand man, chief enforcer, and bastard son. (Non-canonically.) We’ve met him before during the nearly fifty days I’ve been writing about Road House, but he has remained a liminal presence, his dark eyes and blue denim looming in the background like a pale man at a party in a David Lynch film. He accompanies Wesley to Red Webster’s store for their weekly payout but doesn’t say a word. He drives Karpis (unnamed handsome man, in the parlance of the film itself) to fuck the store up later on but never gets out of the car. He laughs as Wesley beats O’Connor for bleeding too much but never throws a punch. He scoffs at Dalton and the Doc as he and Ketchum (the other unnamed goon) spy on them but doesn’t make a move.

It’s at the precise moment when Jimmy is finally set loose, battling Wade Garrett and the entire Dalton-led bouncing staff of the Double Deuce after Dalton cruelly shuts down Denise’s Wesley-approved antagonistic striptease (?!), that things go bad.

Brad Wesley, who moves through life grinning wryly at virtually everyone and everything he sees, has taught his boys well. All of them, even Tinker, have learned to laugh at the misfortune of others, and at nothing else. But Jimmy is Brad’s best boy, and his is the deepest laugh, the fullest laugh, the loudest, the longest—and the last.

Jimmy emits this piercing and preposterous peal—the supervillain laugh to end them all—after blowing up the shack where Dalton’s landlord Emmett lives (and, judging from the size of the explosion, cooks meth) in the middle of the night. So delighted is he by the night’s mean work that he actually stops his getaway motorcycle to look back, take in the extent of what he has done, and enjoy the moment to its fullest. He laughs like a man not acquainted with the concept in any context where the smell of blood and cordite is not on the night wind.

In this moment, Jimmy exhausts the good humor of the Wesleyan Goons with one titanic cackle of pure, joyous malice. No longer are they the cocky cut-ups who run over car dealerships with monster trucks or get beat up in bars. From here on out they exist to kill. Jimmy inhales horseplay and exhales murder. And Dalton is the man who breathes that fire back in.