Posts Tagged ‘music’

The 10 Best TV Needle Drops of 2019

January 7, 20208. Mindhunter: “M.E.” by Gary Numan

After a shaky first season that was all over the map in terms of what we were supposed to feel about its main characters — remember the stiff Holden Ford romance subplot? — Mindhunter settled into a comfortably macabre groove in its second season, chronicling the drudgery involved in tracking down some of the world’s worst people. In the case of the musical montage set to “Cars” singer Gary Numan’s synth stomper “M.E.,” the drudgery is the whole point.

The sequence follows FBI Agents Holden Ford and Bill Tench as they stake out bridges where they hope to trap the perpetrator of the Atlanta Child Murders. It’s a joyless slog of bad sleep, shitty room service, buzzing mosquitoes, muggy weather, cigarette smoke, and ever-shortening patience. Numan’s song, sung from the perspective of a machine that survived the apocalypse alone, provides a surprisingly apt accompaniment to a routine that breaks Ford and Tench down until they feel unmoored from the very humanity they’re trying to protect.

In case you missed it—I know I did!—I wrote about the ten best TV music cues of the year for Vulture.

311. “Dalton and Reno Fight” or: The Music of the Night

November 7, 2019Michael Kamen is the sound of bombast. The go-to orchestral collaborator for a plethora of huge rock acts, including Metallica, Roger Waters and David Gilmour, and Queen, he also had a hand in emotionally soaring recordings by Eurythmics and Kate Bush. His work as a film composer was the accompaniment of choice for action and science-fiction filmmaking in the ’80s and ’90s, too, as he springboarded from his work on the film version of The Wall into The Dead Zone, Lifeforce, Brazil, Highlander, the Lethal Weapon and Die Hard franchises, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen AND Adventures in Babysitting…the list goes on and on. There’s a broad swathe of culture where if you have any fond memories of it at all, you have fond memories of Michael Kamen’s work.

Michael Kamen also contributed the original score for Road House, which is easy not to notice if you haven’t watched Road House several dozen times. In the trifecta of house band leader Jeff Healey and music supervisor Jimmy Iovine, Kamen is undoubtedly the lowest on the totem pole in terms of how you hear the film.

But you definitely hear him here.

When the time comes for Dalton to fight Jimmy Reno (that’s his canonical last name even though it’s never mentioned in the film; the same could be said for Emperor Palpatine in the original Star Wars trilogy, just for the record, and look how well that turned out), there’s no barroom boogie to be found. It’s Kamen’s frightened-sounding strings and call-for-help brass that define this fight. I’ve watched the movie with people who, for whatever reason, notice this right away, and their reaction is almost always incredulous: “What the hell is this music? When did this become Batman?” Incredulous, but delighted, since music this ostentatiously HOLLYWOOD EPIC is just about the only kind I can think of that’s appropriate for this savage escalation of hostilities.

From here on out, Kamen will be the dominant sound of the film. That should tell you something right there.

Music Time: The Juan MacLean – The Brighter the Light

September 23, 2019Variety is the spice of the Juan MacLean. Like label co-founder James Murphy, this core DFA act—comprising frontwoman and LCD Soundsystem alum Nancy Whang and Six Finger Satellite guitarist turned synth wizard John MacLean—has historically taken a magpie approach to dance and electronic sounds. That’s how a Heaven 17 pastiche like The Future Will Come’s 2009 title track can accompany a piano-house banger like “Happy Home,” or how the New Order-esque “Love Stops Here” can share real estate on 2014’s In a Dream with “Charlotte,” a song that sounds more like Beaucoup Fish–era Underworld than anything Underworld have recorded since. Derivative? Pshaw: Whang and MacLean are so proficient and so soulful in their craft that TJM always feels like its own life-affirming entity.

So what to make of The Brighter the Light, an album assembled with sameness in mind?

I reviewed the Juan MacLean’s new singles compilation The Brighter the Light for Pitchfork. (Don’t miss “Feel Like Movin'”!)

Music Time: Type O Negative – None More Negative

September 19, 2019Type O Negative sounded how clove cigarettes smell, how crushed red velvet feels, how black hair dye looks when it stains your bathroom sink. Led by singer and bassist Peter Steele—a towering figure with bone structure to die for, best described as either Evil Thor or Dracula with a gym membership—these Brooklyn-based purveyors of goth metal spent their career exploring the genre’s inherent tension between seriousness and schtick. Originally released on Record Store Day in a limited run and now reissued (on gorgeous green vinyl), None More Negative packages nearly that entire career, featuring all six albums from their years on Roadrunner Records. (Their final effort, Dead Again, was released on another label and isn’t included here.) It’s a suitably massive set for a band best known for its eerie epics.

The best-known of these kick off 1993’s Bloody Kisses: “Christian Woman” explores its subject’s sublimation of sexuality into the crucified body of Christ with all the subtlety of “Ken Russell’s The Devils: The Musical.” It continues with “Black No. 1,” an affectionate send-up of a goth girl’s beauty regimen that launched the band into the public consciousness, via a striking black-and-white video that received heavy Beavis and Butthead rotation. Both songs showcase Steele’s distinctive, vampiric baritone, complete with theatrically rolled R’s and overemphasized consonants (“on her milk-white neck-kkh, the devil’s mark-k”). The man eroticized diction.

I reviewed Type O Negative’s box set None More Negative for Pitchfork. I should note that for me, any number grade above like 6.2 means “you should give this a listen, it’s worth spending some time with.” To the extent that the numbers are under my control (I never have the final say) I grade with that in mind, something that gets lost when people react to the numbers alone but which I believe is borne out in the text of the reviews. Which I hope people read!

Programming note: STC on the Radio

September 16, 2019This morning I appeared live of SiriusXM Volume‘s Feedback to talk about the Do’s and Don’ts of Needle-drops with hosts Lori Majewski and Jim Shearer. If I find a way to listen to it online I’ll let you know!

The Dos and Don’ts of Needle-Drops

September 4, 2019DO: Use well-known songs in unexpected ways that still resonate with the original intent.

Recorded pseudonymously under the Derek & the Dominos moniker, “Layla” is Eric Clapton’s finest moment as a songwriter — an admittedly low bar to clear, since nearly all his best stuff was written by Jack Bruce, George Harrison, or JJ Cale, and also Duane Allman’s contribution to the song should not be underestimated. But still! It’s an outpouring of unrequited love for Pattie Boyd, the wife of his best friend and frequent collaborator Harrison, a way for this guy to reforge his broken heart into a merciless series of interlocking riffs and shout-sung choruses. It concludes with a movement that’s as gentle as the body of the song is frenzied, though it’s no less desperate-sounding for that.

Naturally, Martin Scorsese used it to soundtrack the discovery of half a dozen dead bodies.

Why does it work in GoodFellas? Because it gets right at the heart of the mournful, elegiac feel of the original without simply rehashing its overt emotional content. No one is heartbroken over finding poor Frankie Carbone frozen solid inside a meat truck, except perhaps Mrs. Carbone. But there’s still a sense that something has been lost, that the promised happy ending will never arrive.

More than that, “Layla” plays the same role in Clapton’s career that the murders that result in this sequence play in the career of Robert De Niro’s Jimmy Conway. The song is Slowhand’s masterpiece, and the Lufthansa heist, literally the biggest robbery in American history at the time, was Jimmy the Gent’s. Both Jimmy and Eric were at the top of their very different games here.

Put it all together and it’s a complex, captivating song choice that elevates both the scene it accompanies and the song itself, without the former relying on the latter to do all the dirty work. Scorsese’s library is full of this kind of music cue —as is GoodFellas itself.

SEE ALSO:

• Fargo, “War Pigs” by Black Sabbath

• American Crime Story: The Assassination of Gianni Versace, “Easy Lover” by Philip Bailey and Phil Collins

This one was months in the making: I wrote about how and how not to use music cues in TV and movies for Vulture.

202. I Sold My Soul to Rock ‘N’ Roll

July 21, 2019Or rather, Dalton and Dr. Elizabeth Clay do not sell their collective soul to rock ‘n’ roll. As Dalton flips on the radio to find some mood music, they get as far as one complete recitation of the titular phrase from the song by German heavy metal band Bullet before wrinkling their noses, nodding “no,” and changing the channel. It’s 1989, and a quick listen of that high, multi-tracked vocal chorus reads “hair metal.” It reads inauthenticity, pretty boys, heshers, idiots, poseurs, L.A.—you could just as well say “40-year-old adolescents, felons, power drinkers, and trustees of modern chemistry.”

My pop-cultural awareness began in 1988, when my grandmother got me Appetite for Destruction for Easter. It blossomed fully, to the point where I consider it the dawn of my life as a thinking consumer of popular culture, the very summer Road House came out, in the form of Tim Burton’s Batman. In between there somewhere, I started watching MTV. As such I can assure you that didn’t need to have Nirvana in the zeitgeist to figure that there was something suspect about hair metal at the time. You didn’t even turn your nose up at metal entirely. Metallica were gigantic already, thanks to the video for “One.” Living Colour and Faith No More had absolutely massive alternative-inflected hits with “Cult of Personality” and “Epic,” emphasizing groove rather than shimmy and slink. And though no one appreciates this now, Guns n’ Roses’ oppositional relationship to the poodle-haired likes of Poison, Slaughter, Winger, and their close personal enemies Mötley Crüe genuinely made Axl Rose the John the Baptist to Kurt Cobain’s Jesus Christ. It was that distinct.

Of course I doubt any of this would be relevant to Dalton and Doc. When we first hop into his Benz as he departs the parking garage back in New York (the “what do I look like, a valet?” scene), the station on the radio is 102.7. That’s WNEW, New York’s storied home for classic rock. You weren’t getting anything flashier than “Rebel Rebel” or Thin Lizzy on that. As we see from his friendship with Cody, roots rock—white blues, blue-eyed soul, and most likely the original African-American article as well—are Dalton’s specialty. Sure enough, the moment he stumbles across the opening “These…arms…of…miiiiiiiiine” from Otis Redding’s torch song of the same name, Dalton does not touch that dial.

The interesting thing here is that Bullet are not hair metal, not really. Here, have a look and a listen:

Mustaches? In my hair metal act? Not bloody likely. This is just straight-up party metal, its fast-paced rockin’ boogie part of a transitional sound that combined the increased punk-inspired ripped-denim sneer of the genre as displayed by New Wave Of British Heavy Metal bands with the sweaty good-time glam of Slade, the New York Dolls, Thin Lizzy to a certain extent, and the like. This was a popular move at the time—ask Quiet Riot or Twisted Sister, to say nothing of the Brits themselves—and there’s no reason Germans couldn’t do it too. (One look at the album cover will have you thinking of Spinal Tap’s faster-paced parodies, like “Tonight I’m Gonna Rock You Tonight”; that movie also came out in 1984.)

But Road House needed something that signified all that bad shit I listed above, and whether because it was cheaper or because music supervisor and future Interscope head/Beats by Dre billionaire Jimmy Iovine didn’t want to alienate his Sunset Strip contacts, Bullet got the nod. And insofar as the song sounds like the soundtrack to a barfight, perhaps it wasn’t such a bad choice. Dalton just does to the song what he’d do to its physical equivalent: end it quick.

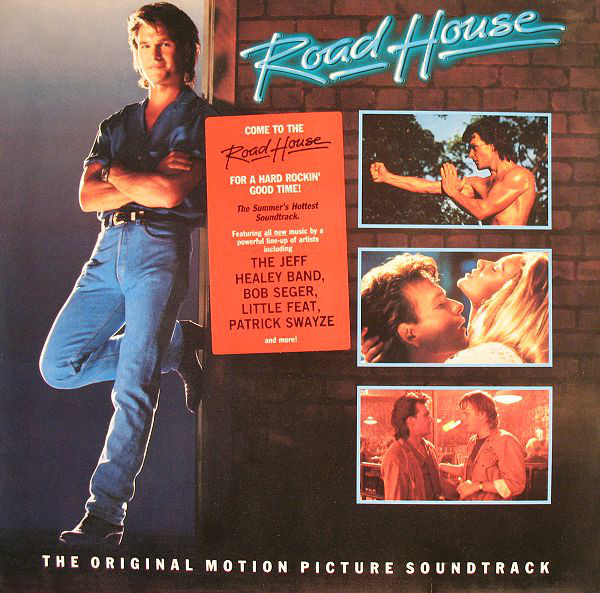

190. Soundtrack

July 9, 2019The thing you need to know about Road House: The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is that it’s not what you think, or perhaps even hope, it is. It’s not a wall-to-wall collection of all of the Jeff Healey Band’s performances from the film. Four of their songs make the cut, but one (“I’m Tore Down”) is only minimally memorable from the movie, and several of the big showstoppers (“Travellin’ Band,” “White Room,” “Knock on Wood (feat. Kathleen Wilhoite)” are nowhere to be found. There’s no snippets of the High Hollywood action-movie score by Michael Kamen, the late great film composer who counted the original Die Hard trilogy and Metallica’s orchestral album S&M among his achievements. “These Arms of Mine” by Otis Redding? That’s in there, thankfully. Alabama’s “(There’s A) Fire in the Night”? No joy.

What you get is a mixture. There’s those four Jeff Healey tracks, including “Roadhouse Blues” and “Hoochie-Coochie Man” from the Denise striptease and Bob Dylan’s self-plagiaristic “When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky.” Otis is on there. Most of the songs are covers—Dylan, the Doors, Willie Dixon, Willie Nile, Maria McKee by way of Feargal Sharkey, Fats Domino. There are at least four songs on here, including two performed (and one co-written) by Patrick Swayze himself, that I don’t think are in the actual movie at all.

You could complain about that, were you so inclined. Me, I’m happy to hear Patrick Swayze’s surprisingly high breathy singing voice over massive ’80s production tricks (giant drums, “ay-oh ay-oh” backing vocals, little glittery synth fills). And anyone who played Prince’s Batman album and Madonna’s Dick Tracy tie-in I’m Breathless as often as I did in middle school knows this much is true:

Music Time: Klaus Nomi – Klaus Nomi

June 18, 2019Klaus Nomi is an easy artist to eulogize. The German-born East Village fixture’s striking, self-made look and soaring operatic countertenor—in layman’s terms, he sang really, really high—brought him to the attention of culture vulture supreme David Bowie. Nomi famously performed with the Thin White Duke on “Saturday Night Live,” hoping for a full collaboration that never materialized. A deal with Bowie’s label RCA, however, enabled Nomi to release two albums abroad before his death, from complications due to AIDS, in 1983. From ANOHNI’s angelic warble to Janelle Monáe’s sci-fi tuxedos, it isn’t hard to find Nomi’s legacy in pop’s outer reaches.

Klaus Nomi, his 1981 debut album, affords us an entirely different opportunity: celebrating Nomi’s music rather than his myth. When an album’s repertoire goes from Man Parrish to Chubby Checker to Camille Saint-Saëns, it’s hard to look anywhere but the music. As beautiful as Nomi was, it’s worth peeling your eyes away from the ghost-white makeup, mountain-range hairstyle, and Tristan Tzara tux to see the truly gifted musician beneath.

I reviewed Klaus Nomi’s wonderful self-titled debut album for Pitchfork.

The 33 Best Industrial Albums of All Time

June 17, 201929. Lords of Acid – Voodoo-U (1994)

Debuting with 1991’s Lust, Lords of Acid were best known for Belgian new-beat bangers with humorously filthy lyrics, the kind of club floor-fillers that hormonal drama club kids could put on their mixtapes. But the rampaging breakbeats, screeching-siren vocals, and double-barreled guitar and keyboard riffs of Voodoo-U were less funny and more frightening. The needles-in-the-red sound was as loud, lewd, and cavernous as the come-hither cover art by the artist COOP, which depicts a fluorescent-orange orgy in the bowels of Hell. Indeed, standouts like “The Crablouse” (a paean to the orgasmic prowess of pubic lice) and the explicitly witchy title track lent the demonic urgency of a summoning ritual to music for people who just really wanted to fuck other people in black mesh tops and vinyl pants. Go ahead, judge this one by its cover.

136. (There’s A) Fire in the Night

May 26, 2019“Hi.”

“Hi.”

“So, you lookin’ for somebody?”

“You.”

You’ve just read the conversation Dalton has with Elizabeth when he spots her and her dress outside the Double Deuce. She’s leaning back against a post, a pose she’ll have occasion to revisit later in the course of their relationship. He’s just finished whipping someone’s ass, which, same. They have an easy and unmistakably sexual intimacy here that the film spends the following scene, depicting their coffee date at a local greasy spoon, blows to smithereens. Yet it’s really only upon repeated viewings that the Doc’s repeated and rather open and vicious skepticism regarding Dalton’s career and character alike becomes apparent. Rather it reads like a tiger and tigress sizing each other up, deciding whether when and where to fuck, knowing they have within them the power to annihilate each other but choosing to do something else to each other instead, something hot to the touch and sweet to the skin. I credit Kelly Lynch and Patrick Swayze with much of that, since there’s hardly a person either character meets at any point in the movie you can’t imagine jumping right into the sack with them with the slightest provocation, and that’s no less true here. But mostly I credit the band Alabama and their song “(There’s A) Fire in the Night.”

Despite spending the better part of my adult life among music critics and music nerds and being both myself, I’ve never heard Alabama so much as mentioned outside country circles. Whatever it is that’s allowed my cohort to deify Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson, make a crossover star out of Kacey Musgraves, turn Garth Brooks’s “Friends in Low Places” into an NYC karaoke staple, place the country affectations of Tom Petty and Stevie Nicks front and center in their respective late-period critical celebrations, and allow Lil Nas X & Billy Ray Cyrus’s “Old Town Road” to happen has never touched the biggest band in the history of the genre.

Listening to this song it is very, very difficult to understand why. Occupying the overlap position in the Bob Seger’s “Night Moves” / Bruce Springsteen’s “I’m on Fire” / The Smiths’ “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out” Venn diagram you didn’t know existed, its minimal, dry guitars and water-on-the-snare-drums ’80s beat tell help singer Randy Owen tell his tale of one great night with one helluva woman. It’s not breaking any kind of ground (except perhaps the tight and expansive-sounding vocal harmonies during the chorus) and that’s the point. It’s guiding you, expertly, through familiar territory—bedrooms you’ve slept in and the people you’ve slept next to in them and your memories of both. Who wouldn’t want to warm their hands by that fire again?

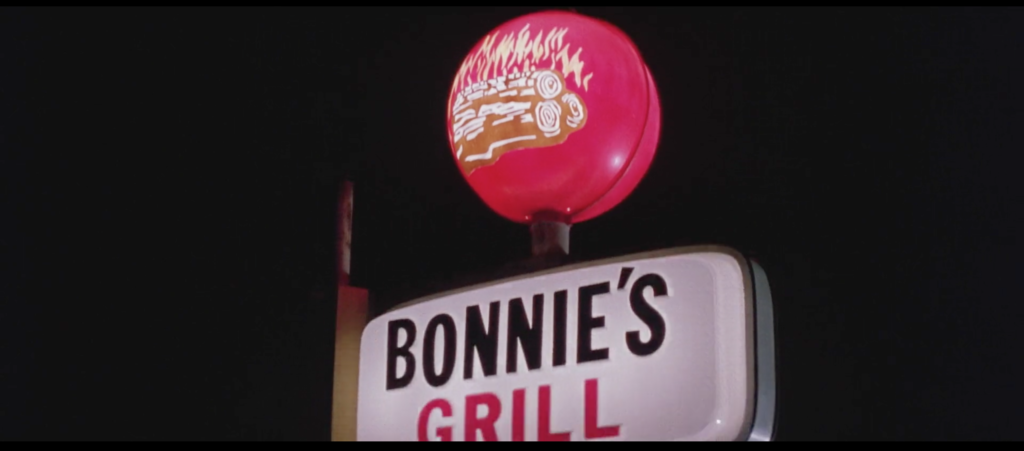

The quick cut that follows Elizabeth’s explanatory “Me” leads us directly to a night sky, blank of stars moon and cloud. The camera descends onto a red orb emblazoned with a roaring fire. It descends further still, revealing the light-up signage of a diner. It’s an echo of the opening shot, which tells you right there that what follows is, in some as yet undefined way, momentous.

But it’s that rhythmic, percussive, low guitar line that sells the mood. When you hear that, and you see the night sky, and you take in the comfortingly ersatz glow of the lights, and you identify the kind of establishment we’re visiting, your mind quite naturally imagines a couple in the moments between when they realize they’re going home together and when they get up to do so. That tension and reserve is all in Jeff Cook’s insistent, somehow twitchy guitar. You pick up on instantly, you contextualize it effortlessly, you know what it’s about before Randy Owen’s singing comes in and proves you right.

Things don’t go great on the date itself, as we’ll see, though again not as bad as they appear at first glance, as we’ll also see. So for me, the music is the message here, and the message speaks true. Not for nothing is our first glimpse of this scene a fire in the night. One is being kindled whether the kindling and the tinder know it yet or not.

When Game of Thrones Plays Sad Piano Music, It’s Time to Freak Out

May 3, 2019For the final stretch of the episode, the ambient sound is muted and a piano melody kicks in. It immediately felt like a callback to “Light of the Seven,” one of your best-known pieces—so, you know, I got worried.

That was 100 percent intentional. When I talked to Miguel [Sapochnik], the director, and when David and Dan came to my studio and we started working on this episode, we all agreed that it had to be a piano piece again, just like “Light of the Seven.”

That was the first time we’d used piano in the show; it really meant something different. You realize Cersei’s up to something and it all blows up. By using it again, we wanted to have the reverse effect. The piano comes in and people go, “Uh-oh, here comes the piano again. Something’s unraveling!” There was little hope throughout the episode. They’ve fought and fought, but the Night King is just unstoppable. Then he comes walking in, and the piano itself represents, like, “This is really it! It’s over!” Then there’s that big twist in the end. It definitely misled the audience because of what they knew from “Light of the Seven,” back in season six. We always treated the music as another character in the show.

081. Don’t Throw Stones

March 22, 2019The most important thing the opening sequence of Road House wants to convey to you is not to throw stones. “Don’t throw stones,” says the man on stage at the Bandstand. “You don’t know,” he continues. “It’s not what you say, it’s what you do,” he elaborates. He then repeats for emphasis “Don’t throw stones” to conclude his statement.

Why this happens is…ah, one of the great mysteries of Road House, right up there with beginning the film in a bar that is not the titular road house, or even a road house at all.

It’s not like the man singing “Don’t Throw Stones” is Jeff Healey, lead singer of the Jeff Healey Band, who provide the live music in every subsequent scene with live music. He’s Tito Larriva, lead singer of Cruzados, the band playing here, and he’s a pretty interesting cat in and of himself, a human Wikipedia k-hole. He started his musical career as lead singer of the Plugz, an LA punk band from the general Decline of Western Civilization/Love and Rockets milieu who did the original score for Repo Man. Much of the band subsequently morphed into Cruzados, which played up their Latino roots and made a kind of Eighties coke-bloat blooz-rock thing out of it. After their breakup, Larriva eventually formed Tito & Tarantula, who provided the musical accompaniment to the Salma Hayek snake dance in From Dusk Till Dawn. Various members of the Plugz/Cruzados continuum also played with Bob Dylan on Letterman in ’84, the drummer played for Izzy Stradlin & the JuJu Hounds, Social Distortion, and Mike Ness’s solo band, and the bassist has worked with Matthew Sweet for years as well as doing various things with sundry rock and roll legends. How they wound up here has, I assume, something to do with the golden ears of music-industry macher Jimmy Iovine, founder of Interscope, co-founder of Beats by Dre, dater of Stevie Nicks, partial inspiration for “Edge of Seventeen” via his intense grief over the murder of his friend John Lennon, and billionaire, married to Liberty Ross, who’s the sister of Atticus Ross, who’s the songwriting partner of and second-ever official member of Nine Inch Nails with Trent Reznor, who once opened for Izzy Stradlin’s other band Guns n’ Roses and who co-starred with Repo Man‘s Harry Dean Stanton in Twin Peaks: The Return and spent years recording for Iovine’s label Interscope before eventually being named chief creative officer of Beats Music, which became Apple Music after Iovine and Dr. Dre sold it to Apple and became billionaires. It’s a small world after all.

<Al Swearengen voice> Anyways, </> Larriva’s face is the second face you see in close-up in Road House, beaten to the punch only by Kevin Tighe. This is an interesting first foot to put forward, not only because Tighe and Larriva’s looks are <Fifty Shades of Grey meme voice> unconventional </a>, but because Larriva isn’t even in the movie after this first scene. But Road House is a film that plays its cards close to its chest in the early going, primarily because despite the skill of the team of action-movie aces employed to make it look good, it’s written (in part by Academy Award nominee Hilary Henkin) as if the writers were randomly but repeatedly struck on the head during the process, resulting in wild miscalculations of the relative weight of what is shown on screen. The Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri are one result. Using Frank Tilghman as our entry-point character even though he’s a grinning ghoul in a bolo tie who could only read as more villainous if huffed fumes and said “baby wants to fuck” is another. Centering the whole opening sequence on a band that you’ll never see again is another.

And there is simply no way to overlook or underplay the presence of the band in this sequence, no. They won’t let you. Our first good look at Larriva, in a vest and pirate-look shirt that are striking even given the Road House fashion baseline, involves him screeching, and I mean it sounds like someone just low-blowed him, “IF YOU LOVE ME BUY ME A BIG TEE VEEEEEE” at the top of his lungs and the top of his register. He goes so hard and so high on this he literally stands on tiptoes and sings down into the mic. He coils his face back into his neck like a snake whose strike is sonic rather than physical. This requires effort, and it does not look like a pleasant effort either. So you know, kudos to Larriva and Cruzados. They left it all out on the stage, a stage they were placed on for some reason.

Now when you first watch Road House you may not realize it, but the message espoused by this song will get under your skin. I’ve found myself singing “Don’t throw stones” around the house. I’ve heard my partner doing the same. We’ve used it as shorthand for watching Road House at all, the way couples text “COAT” at each other to find out if they’re going to get laid if they come home instead of staying out with their friends.

What I’m getting at as this: This sequence is superfluous, its content is a non sequitur (not throwing stones is part of neither the Dalton Path nor the Wade Garret Way), the time spent with it is unpleasant, and the lingering impression is endearing. And here’s the thing about that as it applies to Road House, according to J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings:

“I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and always have done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history – true or feigned– with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed dominion of the author.”

The 50 Best Film Scores of All Time

February 21, 201927. John Williams – Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980)George Lucas’ Star Wars was an absolute blast—and still is, anytime you’re flipping through channels and catch the Death Star attack run. For the sequel, Lucas and company went a bit deeper, got a bit darker, and added more mystical light and romantic heat. So did Lucas’ go-to composer.Between Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, and, of course, that first Star Wars, John Williams was already responsible for some of the most recognizable film music ever recorded, combining a pop musician’s ear for hooks with a sense of scale commensurate with galaxies far, far away. In Empire, he expanded the sonic template he established for the original film, creating his richest and most varied set of compositions yet. Foremost among these is “The Imperial March,” the brassily sinister martial theme associated with Darth Vader. “Yoda’s Theme” is its opposite—soft and sweet, its melody seems to slowly levitate. A swoon in musical form, “Han Solo and the Princess” is an intensely romantic theme for that literally tortured love affair. Empire is the definitive Star Warsscore, featuring songs so intrinsic to Lucas’ fictional universe, it’s hard to believe they weren’t there from the start.

The 50 Best Film Soundtracks of All Time

February 19, 201946. Paul Giovanni – The Wicker Man (1973)

The Wicker Man is never what you expect it to be. Like its hero, a Scottish police sergeant trying to find a missing girl in a pagan community, the New York musician Paul Giovanni was a stranger to the old Celtic folkways he was hired to investigate for Robin Hardy’s haunting horror film. His outsider’s ear for both the then-booming British folk scene and its ancient antecedents made the music he composed the ideal mirror for such a twisted journey. The opening song is a tightly harmonized adaptation of Scottish poet Robert Burns’ “The Highland Widow’s Lament,” nearly abrasive in its mournful mountain-air beauty. Sex is a frequent topic for the film and music, rendered in forms both profane (the absolutely filthy drinking song “The Landlord’s Daughter”) and sacred (“Willow’s Song,” the set’s dirty-minded but gorgeous standout). Rousing community singalongs and sparse hymns of ritual sacrifice weave conflicting narratives of their own. It’s a soundtrack that casts strange shadows and remains ungraspable, like a tongue of flame.

032. Sh-Boom

February 1, 2019Originally recorded by doo-wop group the Chords, who charted with it in 1954, “Sh-Boom” became part of the pop-culture firmament largely because of a cover version by the Crew Cuts that was also a hit later that year. Both versions are the kind of gleeful pure-dee nonsense that make doo-wop such a fun genre to pronounce, let alone listen to. While Chords’ rendition has a jaunty swing to it, the Crew Cuts’ whitebread revamp emphasizes the gliding, carefree, “life could be a dream” side of the song. It sounds like a Sunday drive.

Of course, most people content themselves with driving on the right side of the road, Sunday or any other day, whether they’re listening to “Sh-Boom” or “Yakety Yak” or “Symphony of Destruction” by Megadeth. This is not just because it’s the law, or because it’s much safer not to drive into oncoming traffic. It’s because staying in your lane allows you to chart a long straight course, and a long straight road is the most fun kind to drive. The Germans modeled a whole genre of music after it and everything.

When we see Brad Wesley driving his red convertible (a Ford, possibly ill-gotten from Strodenmire’s ill-fated Ford dealership) with the top down on a bright sunny day, the fact that he’s singing “Sh-Boom” fits. It’s that kind of song. Wesley is also swerving from one side of the road to the other and back, over and over, like a sine wave, like a snake. This, too, fits. He’s that kind of person. But the actual driving process deserves closer examination.

Until Dalton passes by headed in the other direction, nearly getting run off the road in the process, there isn’t another car in sight. Wesley has the road all to himself. He could comfortably cruise along, taking in the air and the scenery. He could floor it if he felt the need for speed. (“He’s go the sheriff and the whole police force in his pocket,” Red Webster tells Dalton later in the film; the line is likely intended to explain why crimefighting in Jasper is entirely the province of bouncers, but it explains a lot of other things too.) This is what normal people who enjoy a nice drive would do.

As anyone who’s whipped around an empty high-school parking lot could tell you, rocking the steering wheel back and forth like Wesley does creates a push-pull swerving sensation that’s much more enjoyable in theory than in practice. If you’re a 17 year old looking for a quick thrill when you’re all out of kratom or whatever, sure knock yourself out. But to drive that way over a significant distance is less fun than just driving straight, not more.

Ben Gazzara sells the nauseating joyride as well as you’d expect from an actor who, prior to Road House, created the role of Brick in Cat in a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams. And indeed we can take Wesley’s glee as entirely sincere, but not because he’s having fun driving in and of itself. He has gone out of his way to make his drive less physically enjoyable, because the thrill of being a gigantic asshole and recklessly endangering the lives of others more than compensates for the loss.

This is the kind of man Brad Wesley is. He can hey-nonny-ding-dong-alang-alang-alang his way back and forth across every inch of asphalt in Jasper and none can say him nay. That’s worth a crick in the neck.

Music Time: Trent Reznor/Atticus Ross – Bird Box (Abridged) Original Score

January 16, 2019Starting with 2008’s sprawling collection of instrumental work Ghosts I-IV (released under the Nine Inch Nails aegis) and accelerating with 2010’s Oscar-winning score for David Fincher’s The Social Network, the instrumental side of Trent Reznor has effectively shared equal billing with the more traditional industrial rock that made him a superstar. Never one for half measures, Reznor clearly sees the film-soundtrack work done alongside his longtime composing partner Atticus Ross as a chance to flex. “We aim for these to play like albums that take you on a journey and can exist as companion pieces to the films and as their own separate works,” Reznor wrote recently. He’s not kidding: The duo’s score for Fincher’s 2011 film The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, for instance, is 15 minutes longer than the movie itself.

In announcing the release of Bird Box, the score for Netflix’s treacly Sandra Bullock survival-horror film of the same name, Reznor described it as a way of presenting the audience with “a significant amount of music and conceptual sound” that didn’t make the film’s final cut. Even then, that “Abridged” parenthetical in the title points toward “a more expansive” version of the album due later this year. It’s just as well since what Reznor and Ross have created is better than the movie they created it for. It does exactly what good soundtracks are capable of doing, and what they expressly intend for it to do: Emerge as a rewarding experience in its own right.

I reviewed Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross’s Bird Box score for Pitchfork.

The 10 Best Musical TV Moments of 2018

January 1, 201910. Westworld: “Do the Strand” by Roxy Music

Few shows have been as guilty of music-cue abuse as Westworld. Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy’s leaden and labyrinthine sci-fi parable has folded an entire Spotify playlist of classic alt-ish rock songs into its narrative via instrumental arrangements by composer Ramin Djawadi. Give a listen to his best-in-field work on Game of Thrones and it’s painfully clear he can do much better than player-piano Radiohead or Japanophile remixes of Wu-Tang Clan’s “C.R.E.A.M.” or whatever.

This is what makes Westworld’s in-world cranking of Roxy Music’s boisterous 1973 hit “Do the Strand” so remarkable. Blasted at full volume by James Delos (Peter Mullan), the Scottish founder of the Westworld theme park (and, unbeknownst to him, one of its core artificial-intelligence experiments), glam rock’s answer to Led Zeppelin’s “Immigrant Song” sounds as unexpected in the dour songscape of this series as Delos’s “dance like no one is watching” behavior looks. Yet Bryan Ferry’s hedonistic lyrical promise of the next big thing — “There’s a new sensation, a fabulous creation” — and Brian Eno’s retro-futuristic flourishes as the band’s in-house effects guy fit Westworld’s themes like they were engineered in a lab to do exactly that.

This is always one of my favorite pieces to do: I wrote about the 10 best music cues of 2018 for Vulture. Definitely stick around for Number One.

Music Time: David Bowie – “Glastonbury 2000”

January 1, 2019According to many British music publications, David Bowie’s headlining set at the Glastonbury Festival in 2000 is the greatest performance in the history of the legendary event. (NME, ever effusive, called it “the best headline slot at any festival ever.”) But it’s greatest that’s doing the work here, not performance. It’s not individual highlights that make the set so fondly remembered, but the overall gestalt. Like the old saw about climbing Everest, Bowie’s Glasto set mattered because it was there.

By the time he took to the Pyramid Stage, Bowie had spent 15-odd years in the mainstream-music wilderness—first, post-Let’s Dance, making milquetoast megapop no one particularly liked, then rebuilding his reputation with experiments in everything from Pixies-inspired garage rock (Tin Machine) to concept-album Eno-industrial (Outside) to a Nine Inch Nails/Goldie hybrid version of drum ’n’ bass (Earthling). Different people liked these experiments at different times and in different amounts, though never at the level of his 1970s and early-1980s output. (Earthling rules, for what it’s worth.) During much of that period, his greatest hits were largely retired from service in his live sets.

But now, with a generosity of spirit as lush and flowing as his hair—which hadn’t been that long since Hunky Dory—Bowie was back! Resplendently coiffed and backed by a familiar band of musicians (including pianist Mike Garson, bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, and guitarists Mark Plati and Earl Slick, all of whom worked with the star for years), the once and future king of art pop was welcomed by the sprawling home-country crowd like Arthur Pendragon returning from Avalon.

I reviewed David Bowie’s Glastonbury 2000 live album for Pitchfork. Giving a mixed review to David Bowie. Hell of a thing.

Music Time: Metallica: “…And Justice for All”

December 31, 2018…And Justice for All is the biggest metal band’s best album. I see you, Master of Puppets people, but I’ve strapped on the blindfold of Lady Justice and let the scales tip where they may: Justice wins. The songwriting of singer James Hetfield and drummer Lars Ulrich is their most complex and vicious, retaining the power of their early thrash while jettisoning its simplistic schoolyard chants and avoiding the less-compelling hard rock tendencies to come. Use, abuse, experience, and enough beer and Jägermeister to make Keith Moon drive a luxury car into a swimming pool had tempered Hetfield’s reedy yell into something fuller and more forceful, with none of his later cigar-chomping bluster. The lyrics are a ground-level portrait of bureaucratic order pushing down on people too powerless to fight back. And the sound is nearly industrial in its ear-killing intensity, a piece of serrated steel designed to carve you and leave its nihilism in the wounds. Oh, and maybe you’ve heard this: You can’t hear the bass.

I reviewed the excellent reissue of Metallica’s masterpiece …And Justice for All for Pitchfork.