Posts Tagged ‘dalton’

014. Carrie Ann looks at Dalton

January 14, 2019I’ve been saying this for years, but it’s risky to write about what turns you on. When I first started reading the work of the woman who’d eventually become my partner it was hot in such a raw, unvarnished way—to me anyway, which explains a lot about what happened afterwards—that I wondered if she felt particularly bold or scared or vulnerable just putting it out there. Sex scenes are one thing, pretty much everyone who has sex enjoys it and even people who don’t usually enjoy watching it. But sex scenes, or scenes of sexuality, that tease out or revolve around a specific fetishized behavior aside from the basic forms of erogenous-zone contact or what have you…writing that stuff, or writing about that stuff, is in its own way as revealing as taking off your clothes.

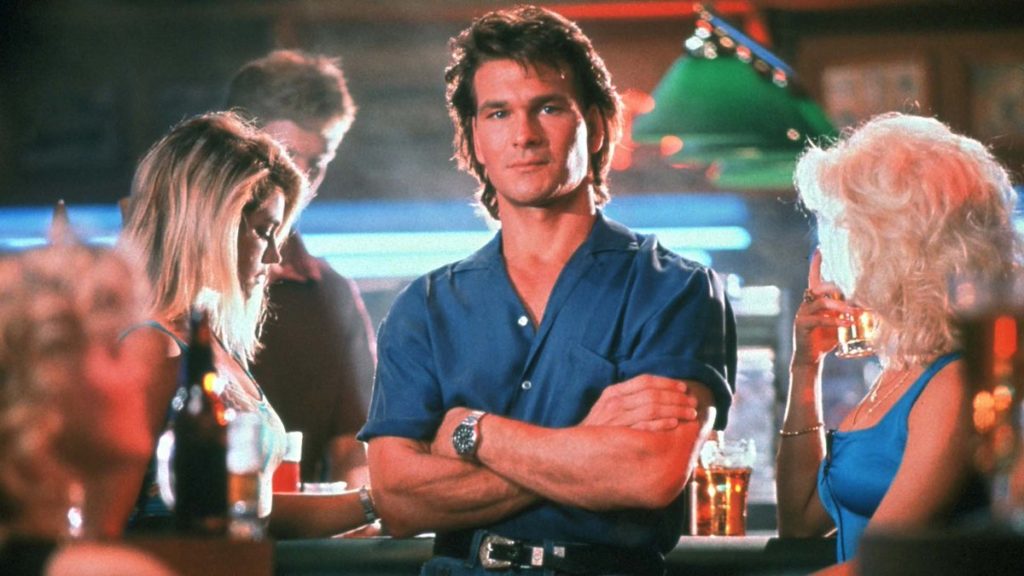

Anyway, the scene in which Double Deuce waitress Carrie Ann sees Dalton nude is the single most erotic thing I’ve ever seen in a movie.

Played by Kathleen Wilhoite in one of the film’s least bizarre, most straightforwardly fun performances, Carrie Ann is what might have been called in earlier times a broad. She’s got a great brassy voice that she uses to dress down the Double Deuce’s belligerent bad element when Dalton first arrives and needs to get the lay of the land, eg. “Don’t let him bahhhther yew—Morgan was born an asshole and just grew bigger.” She’s the only female member of the core cast we ever see throw hands, when she smashes a bottle over a dude’s head during the movie’s first big brawl. Later in the film she’s revealed to have a terrific blue-eyed-soul voice, which she demonstrates by taking lead vocals for the Jeff Healey Band’s cover of “Knock on Wood.” (“I didn’t know she could sing!” announces the most adorable member of Dalton’s bouncing crew as the two men look on, grinning from ear to ear.) During the early-morning breakfast-delivery run she makes to Dalton during this scene, she’s mostly there to dispense greasy food and hard truths about the trouble he’s getting himself into at the bar, with a fuck-em-if-they-can’t-take-a-joke smile on her face the whole time.

That’s what makes her reaction to Dalton’s bare ass, and implicitly other parts, so powerful. This beautiful man’s naked body strikes this seen-it-all chatterbox dumb.

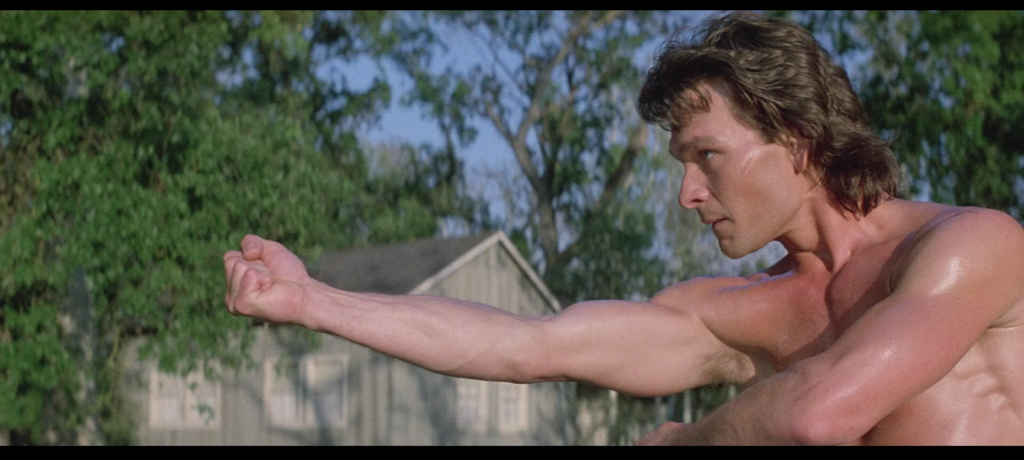

And like, on one level, yeah, of course it does. I mean, look at him.

Carrie Ann isn’t the only woman bowled over by Dalton’s attractiveness—you’ll recall, perhaps, Denise sizing him up—and she’s certainly not the only person to look at him in this way either. Indeed, the way women look at Dalton is largely indistinguishable from how men look at him, which is part of why the “male swayz” is such a standout phenomenon. The gaze of Carrie Ann, Denise et al conditions us for the gaze of Emmet, Wesley, Jimmy, Karpis, Tilghman and so on.

But no one looks at Dalton the way Carrie Ann does, because she’s the only person we ever see looking at him naked. (Dalton and Elizabeth are fully clothed when they start having sex; when they go for round two in the nude, it’s shown from a distance. We never see what Doc looks like when she looks at her man’s bare body.)

Carrie Ann shows up with breakfast the night after Dalton cleaned house at the Double Deuce, waking him up. He moans and groans and staggers out of bed like he’s hung over, which is funny since after he got home from work all he did was look across the way at Brad Wesley’s pool party in between chapters of the Jim Harrison novel he stayed up late reading. (For real.) But he sleeps in the buff, so when he slips out of bed, there he is.

Carrie Ann stops seemingly in mid-thought, like a rabbit in the headlights. Her eyes glaze. Her mouth opens. She gasps audibly. Her eyes heat up and a smile of pure horned-up delight briefly crosses her lips. Finally, she controls herself and looks away, abashed. There’s one final double entendre when he asks her how she tracked him down—”So how’d you find me?” “Oh! I, uh, it wasn’t too hard. I mean…you know what I mean.”—and by then he’s put on his jeans and begun his morning stretching-and-smoking routine. The scene moves on.

But I sure haven’t. Carrie Ann experiences something very rare for women in film: a moment of unguarded lust and guileless sexual objectification of the male body. She’s not doing this for Dalton, or even with Dalton’s observation and reaction in mind, since he’s not looking at her and has no idea what she’s doing. She stares and gasps and grins at him for no one’s entertainment or arousal but her own. Indeed, she’s sure to cut things off before he has a chance to notice and react. Perhaps this is done for his benefit, so as not to embarrass him, or for her own, so as not to embarrass herself. But the effect is that of a woman experiencing sexual desire in a totally personal, private, inviolate way.

What does this mean for us? We become voyeurs of another person’s voyeurism. And because her voyeurism is so accidental and unexpected, there’s a purity to it that avoids the fetish’s usual connotation of sleaze or outright violation, which lets us off that particular hook in turn. Without anyone trying, she gets to see something that turns her on, and we get to see her get turned on, and then it’s over. The eroticism of the moment is brief and blameless and beautiful. The fact that Carrie Ann is herself lovely helps, but it’s almost incidental. Arousal is lovely. Desire is lovely. And here they are, embodied in a moment and preserved, as in amber.

013. Men look at Dalton

January 13, 2019When men look at women in Road House it means trouble. Steve the bouncer ogles his teenage would-be conquests. A husband with a cuckold fetish and a goofball barfly fetishize and fondle his wife’s breasts. A belligerent drunk starts a knife fight when people try to prevent him from watching his girlfriend dance on a table. Brad Wesley throws an absurd string-bikini pool party for his army of goons. A horned-up soldier rushes the stage in the topless bar where Wade Garrett works. Denise strips in front of the Double Deuce’s wolf-whistling bad seeds under Wesley’s approving eye in a strange act of macho-sexual judo. With two exceptions—the superimposition of the film’s title over an anonymous woman’s rear end, echoed by Wade hating to see Doc leave but loving to watch her walk away—the traditional male gaze is an indication that something is wrong.

When men look at Dalton, it’s different. And men look at Dalton alright. All kinds of men, for all kinds of reasons.

When they first meet, goons like Karpis and Jimmy lock eyes with Dalton in staredowns that sizzle with psychosexual challenge. (In Jimmy’s case the sexual element is made abundantly, infamously clear later on in the film.)

Frank Tilghman stares at Dalton and smiles over and over again, like a man seeing his favorite meal on the way over to his table. “I want you,” he says during one such glance, followed in that same conversation with a knowing “I thought you’d be bigger.” “He’s good. He’s real good,” he says to another man during another. Honestly Tilghman is such a strange character that he probably deserves an essay series of his own, but his open near-worship of Dalton is a start.

Both Dalton’s friendly landlord Emmet and his evil neighbor Wesley watch Dalton perform tai chi, shirtless and slick with sweat. Wesley has the look you often see on the faces of men in movies who’ve caught a glimpse of a topless woman through a window. Emmet looks like he’s questioning a whole lot about the world and his place in it.

Wesley even watches Dalton and Elizabeth have sex. You might think that Elizabeth is the object of the gaze here, but at no other point in the film does Wesley bring her up as a point of contention between himself and Dalton, even though their relationship does seem to catalyze a new level of hostility between the two men. There’s no “she’s mine, if I can’t have her no one will,” and when he talks to her about Dalton it’s to express regret that she’s wound up with a lowlife drifter, not to threaten her to come back to him. He only has eyes for Dalton.

And honestly, who wouldn’t? Look at him.

By constantly showing us men who visually appreciate Dalton, Road House models behavior for its primarily male audience. Which is not to say women were not a target as well. Surely a decision was made to capitalize on the sex symbol status of the man who plays Dalton, Patrick Swayze, for the women in the audience—by then he’d starred in the smash hit Dirty Dancing, and another romantic blockbuster, Ghost, was on the horizon; his sex scene with Kelly Lynch set to Otis Redding beat the pottery scene with Demi Moore set to “Unchained Melody” to the punch.

But Road House‘s life since its theatrical release has been one of basic-cable afternoon screenings for dudes. I myself never caught it that way, but I first saw it during a Road House/The Warriors/The Road Warrior triple feature with a bunch of drunk and high friends, which is more or less the same idiom. I came away from my first viewing feeling just an unbelievable amount of affection and admiration for Patrick Swayze, an actor I’d never really thought about at all before. When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, I held a Road House/Steel Dawn/Point Break triple feature at my place and charged everyone a twenty-dollar donation to pancreatic cancer research for admission. I love Patrick Swayze just as I love Dalton. I believe these shots of men looking at Dalton, capturing the blend of admiration, envy, desire, and awe they feel when they look at him—call it the male swayz—are, at least in part, the reason why.

011. First glimpse

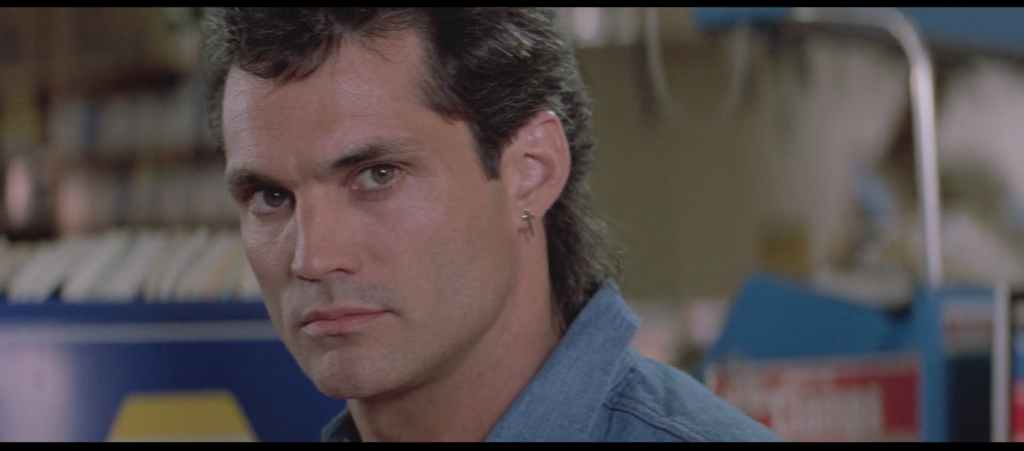

January 11, 2019In the beginning was the Mullet, and the Mullet was with Dalton, and the Mullet was Dalton.

Mullet-based humor is now so old that I remember having to make sure the audience knew what mullets were when I wrote a sketch about them for my comedy group in college—in 1998. That isn’t what this about. The very first shot of Dalton in Road House shows the back of his head for a reason.

Please note that the director of photography on this film is Dean Cundey. His credits as a cinematographer include Jurassic Park, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Back to the Future, The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, The Fog, Escape from New York—a murderer’s row of SFF classics from directors who convey story primarily through image and character through portraiture. The shot of Dalton’s mullet establishes him as recognizable first from behind, and then in silhouette. No one else in the movie has a head of hair anywhere near this magnificent and distinctive.

As the camera tracks in on Dalton, we watch him survey the crowd at the filled-to-capacity hotspot at which he currently works. He nods along absently to the beat of the music played by the band on stage, so absently in fact that his head tilts upward with the beat rather than downward. It reads more like a gesture of regal approval and command than a guy mildly rocking out, because that’s what it is. (He’ll make similar gestures a minute or two later, when he wordlessly instructs the bouncers in his charge in how to handle some ruffians.) At that moment, all is right with his world. The cooler has cooled.

Then things heat up. Dalton turns his face toward the camera and his eyes focus. A cut along his eyeline reveals what he’s looking at: a man soliciting a woman as if she’s a sex worker, putting a hundred-dollar bill down on the table for her services. Insulted, she takes out a knife and slams it downward, pinning the money to the table. Insulted in turn, the man kicks her chair right between her legs, tipping it over and knocking her on her ass. Bouncing and cooling ensue.

Pay close attention to the editing here, by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link. Between them, and sometimes in tandem, these men cut Die Hard, RoboCop, Predator, Commando, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Tombstone. They’re as responsible for establishing the rhythm and language of contemporary action-thriller cinema as any two people in the business. Do they cut from Dalton to the troublemakers once the trouble has started? No. They cut slightly before, after the sound of a single broken glass and a raised voice, in a jam-packed nightclub with a rock band playing.

Urioste and Link are not likely to have done this by accident. They’re establishing Dalton’s near-superhuman ability to detect, defuse, and defeat any bar’s bad element. They’re demonstrating what happens when his cooler-sense starts to tingle.

Thanks to these three top-tier filmmakers, Dalton’s mullet is as meaningful and memorable as Batman’s cowl or Darth Vader’s helmet.

010. Denise

January 10, 2019Who is Denise? Denise is Brad Wesley’s girlfriend, and the most stylistically sophisticated and culturally aware human being in the entire film. You can tell this at first glance, and glances are really all you get. Her lines are minimal: She rebuffs a vulgar proposition, makes one of her own, and…that’s it, I realize now. That’s all Denise gets to say.

But she makes an impression, I can tell you that much, and she does so long before she enthusiastically strips on stage at the Double Deuce with Wesley looking on approvingly, some time after he beats her off-camera for coming on to Dalton. Even when the bar looks like it might collapse around her ears at any moment, even when its atmosphere resembles a Tables Ladders and Chairs match more than a nightclub, she’s there with her girlfriends, leader of the pack, out on the town and dressed to kill.

Sure, she attends Wesley’s ludicrous backyard pool party/dance party/orgy/whatever it is. But when he’s not around and she gets her first good look at Dalton, the camera whip-zooms in on her dilated-pupil look of desire like Cupid’s arrow. It’s such a jarring moment in this straightforwardly shot film—easily the most cinematographically adventurous thing that happens—that in any other movie it would indicate the start of a major plotline.

But it goes nowhere beyond her asking Dalton to go to her place and fuck, an offer she cleverly cushions with a rhetorical flourish: “Would you be shocked if I said ‘Let’s go to my place and fuck?'” Yeah, it sounds like the writers don’t understand that “If I said you have a beautiful body, would you hold it against me” is a play on words. But her forthrightness is admirable, as is the fact that she still has her own place and isn’t relying on Wesley’s largesse. Like O’Connor, whom he beats for the crime of bleeding, she knows you can’t count on staying on Brad Wesley’s good side.

By the end of the movie that’s not an issue anymore. Freed from Wesley’s influence and the watchful eyes of his goons, she’d theoretically be able to enjoy more nights out with the girls, in a renewed and revamped Double Deuce that better suits them. But we don’t know. Denise’s final moment in the film is being ridiculed by an uncharacteristically ugly Dalton as a pet that Wesley should keep on a tighter leash. She’s afforded no payback for that slight, or for Wesley’s abuse. Imagine if she’d wielded one of those shotguns instead of, say, Pete Strodenmire, the guy we see in a grand total of one scene before his car dealership gets run over by a monster truck. That would be something, right?

But there’s nothing instead. Awkwardly covering her bare breasts, she gets dragged off stage, off camera, and out of the movie. Freaking Tinker gets a better redemption arc. Still, during that one shot, there’s the promise of a whole world in her eyes—her apartment’s decor, her girls’ nights out, her love for buoyant late-’80s dance pop, her desire for a relationship with Dalton worth risking Wesley’s wrath for, even if it’s only for a night. She is Road House‘s great mystery, its Mona Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam. Who is Denise? We’ll never know. But she’s in there somewhere.

008. “$5,000 up front. $500 a night. Cash. You pay all medical expenses.”

January 8, 2019According to 2017 research by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median pay for a security guard or gaming surveillance officer, the closest career to bouncer or cooler that the BLS tracks, was $26,900 a year. Assuming Sundays off and not counting the stipulated coverage of all medical expenses, a conservative estimate of the yearly salary paid to Dalton by Frank Tilghman for his services as a cooler at the Double Deuce comes to $328,259.17 in 2019 dollars.

Tilghman prefaces his offer of employment to Dalton by saying “I’ve come into a little bit of money [and] I’d like to make a better life for myself.” Based on the elaborate redesign for the Double Deuce unveiled later in the film, he’s not kidding about the money. But the redesign, which we see him penciling on drafting paper the night Dalton shows up in Jasper, is meaningless if the volume of patrons required to make a bar that large and expensive a worthwhile investment doesn’t materialize. As Dalton himself puts it, “People who really wanna have a good time won’t come to a slaughterhouse.”

Dalton is the man who puts a stop to the slaughter. Though neither man knows it will happen when they make their deal, Dalton also breaks the back of the local organized-crime outfit, which according to Red Webster takes a minimum of “ten percent—to start” of gross income from every business in town. In fact, by personally murdering five of the town’s most violent criminals, beating a dozen or so others badly enough that they will never return, and driving one more to a Damascene conversion by dropping a stuffed polar bear onto him in a rich lunatic’s basement, Dalton eliminates the town’s bad element altogether.

Three-twenty-eight large is a bargain.

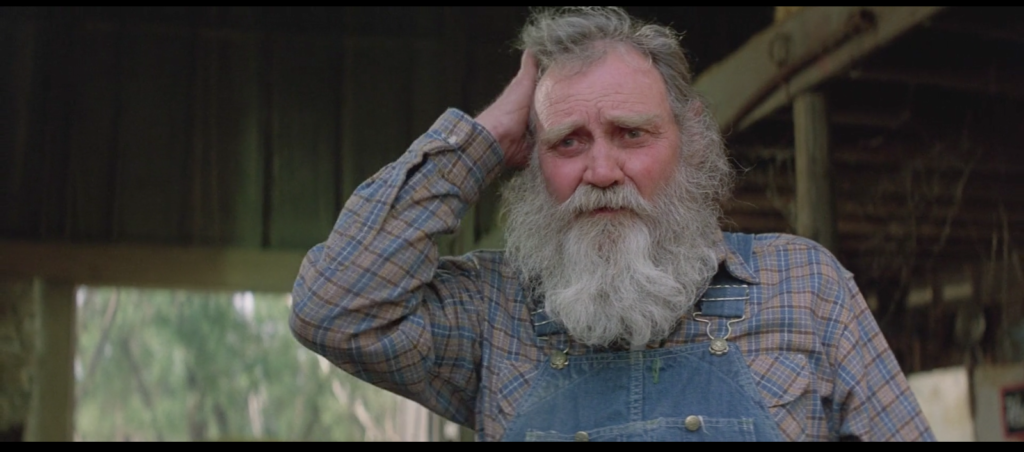

006. Church

January 6, 2019Emmet: It ain’t the money, you understand, but if I don’t charge you somethin’ the Presbyterians around here are likely to pray for my ruination. How does $100 a month strike you?

Dalton: Fine.

Emmet: You can afford that much?

Dalton: If it keeps you in the good graces of the Church.

Emmet: Ain’t it peculiar how money seems to do that very thing.

—Road House

David Brent: [singing] “Who is wrong and who is right? Yellow, brown, black or white?” The spaceman, he answered, “You no longer mind. I’ve opened your eyes—you’re now colorblind.” Racial. So,

—The Office

Aside from having His Name taken in vain, God doesn’t figure much into Road House. That’s worth paying attention to. In the roughly contemporaneous Rocky franchise Rocky wears a crucifix and often prays prior to a big fight, which particularly during his showdown with Soviet behemoth Ivan Drago takes on added political weight. Rambo is crucified in First Blood Part II. Yet despite a down-home setting conducive to that old time religion, the closest Dalton gets to spirituality by contrast is doing tai chi outside with his shirt off and referring to his study of philosophy at NYU as “man’s search for faith.” Though he and Dr. Elizabeth Clay do indeed meet when he goes to the hospital with one of the wounds of Christ—a stab in his side—it’s on the left side rather than the right, and rather than probe it, like Thomas, she seals it, like a doctor. No one’s making room for the Holy Spirit here, so to speak.

Played by “Sunshine” Parker, who was just 61 at the time of filming but looks like something hobbits might meet in an ancient forest, Emmet rents Dalton an outrageously huge and beautiful loft apartment open to nature with a view of the nearby water for one-fifth of what Dalton earns as a cooler every single night. He likes his horses and he likes company, and there you have it. Those are his wants and needs, and a few extra hundred dollars a month are superfluous. Why charge rent when it’s no skin off your ass not to? Why participate in a system that offers you nothing but things you don’t really need?

That this appears to be his attitude toward organized religion—and the film’s, since Emmet and Dalton are consistently portrayed as operating with unerring moral compasses, at least until Dalton commits the sin of despair at film’s end and pays for it dearly—is delightful to me. Sure, it seems thrown in there like it’s a David Brent–style attempt to open people’s eyes, as if anyone’s counting on Road House for enlightenment. But it works. There’s no Jesus, no Bible, not even any talk of praying to the Good Lord in his own way. There’s just a funny old codger summing up Christianity as a chauvinist capitalist scam. Brad Wesley with hymns, pretty much. When you’ve got the man himself to make your life miserable while singing “Sh-Boom,” who needs the hassle of godbotherers?

005. “You’re gonna be my regular Saturday night thing, baby!”

January 5, 2019This is Steve. (The one on the left.) Steve is a bit of an anomaly in the world of Road House, a bit of an enigma. He’s one of four people abruptly fired from the Double Deuce by Dalton when he assumes control of “all bar business” (per Tilghman) as the joint’s cooler. Morgan, a cantankerous thug played by hardcore wrestling legend Terry Funk, is fired for not having “the right temperament for the trade,” the wisdom of which he demonstrates by later attempting to murder Dalton on behalf of Brad Wesley. Pat, the weaselly bartender played by L.A. punk legend John Doe, is fired for skimming from the till. He too attempts to murder Dalton on behalf of Brad Wesley (his uncle), multiple times, indicating that Dalton has made another correct judgment call. Judy, a wiry waitress played by Sheila Caan (ex-wife of James Caan and ex-girlfriend of Elvis Presley), is fired for dealing drugs in the bathroom. She does not attempt to murder Dalton on behalf of Brad Wesley or anybody else for the rest of the film, indeed she doesn’t appear in the rest of the film at all, indicating that perhaps a reformist approach may have borne more fruit in her case.

Despite being a heck of a physical specimen, Steve is not a pro or even semi-pro ass-kicker like his coworkers Morgan and Pat; the one fistfight in which he participates ends with him groaning into a mirror about the shiner temporarily disfiguring his beautiful face. He’s not a drug dealer or a legbreaker or involved in any organized-crime capacity at all. Steve’s not a fighter, he’s a lover. The problem is he that loves young women who are visibly below drinking age, which may in fact be putting it generously.

We first meet Steve (Gary Hudson, a hunk) when he blows off the idea that he should break up a rolling-on-the-floor fight between two aggrieved pool players (“fuck ’em, they’re brothers”) in favor of telling a bosomy patron, whose fake ID is probably Mclovin-level, that he gets off at 2am, and (should she play her cards right) she could get off shortly thereafter. Later that night he incurs the shiner, presumably ruining his plans. In our next encounter he’s antagonistic toward Dalton during the meeting in which he fires Morgan and Judy and lays out the rules everyone will be expected to follow going forward.

Then comes Saturday night. When Beverly and Agnes, two women in, let’s say, his target demographic, get stopped at the door for presenting a Sears credit card as ID, Steve swoops in to wave them through. Why? Because he’s been thinking about Agnes, and tonight is a very special night: the night he’ll roger her in the supply room beneath a St. Patrick’s Day banner during his break. (Steve invented the “I was on a break” excuse, which he uses to no avail as he slides his high-cut blindingly white briefs back up and protests his firing. Eat shit, Ross Geller.) Stripped naked as a jaybird and rhythmically fucking her from behind standing up (everyone does their best work on two feet in this film), he pays her the ultimate compliment: “You’re gonna be my regular Saturday night thing, baby!” Then Dalton walks in, looks on in bemusement for longer than is perhaps necessary, then breaks up the party and sends Steve packing. (Dawn Ciccone, the actor who plays Agnes, has a “whoopsie daisy!” look on her face afterwards that’s one of the most endearing things in the whole movie.)

Road House is like Shakespeare in many respects, but foremost among them is its propensity to coin phrases. Most of these—getting “nipple to nipple” as a euphemism for sex, “balls big enough to come in a dumptruck” as an elaboration of “balls of steel,” replacing “does a bear shit in the woods?” with “does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?”—are wonderful, vulgar, stupid, and all but impossible to imagine anyone saying in the real world.

But “my regular Saturday night thing” is different. It’s an effective encapsulation of an entire type of relationship: people who like having sex with each other enough to do so regularly, but who are otherwise indifferent enough to each other to keep it on a relatively light schedule, with no real desire to treat it as much more than a thing they do on Saturday nights. Other people might have stayed home to watch the NBC comedy lineup (227, Amen, Golden Girls, Empty Nest, good stuff, I was a religious viewer). Still others might well have come to the Double Deuce, but to dance on tables, or to stab the people who try to get those people to stop dancing on tables, which is the other thing that happens on this fateful night.

But Steve’s desire to be a part of Agnes’s life that begins when they enter the stockroom and ends, I’m guessing, about three minutes later is heartfelt and modest and mercenarily horny enough to resonate beyond the walls of the Double Deuce. It’s the reason Loverboy was working for the weekend. It’s why the Bay City Rollers chanted “ESS AY TEE-YOU-ARE DEE-AY-WHY…NIGHT,” even if their teenybopper audience didn’t realize it. Readers of this series almost certainly have never thought of their sexual partners in terms of getting “nipple to nipple,” but I’d wager more than a few of you have had, or have been, a regular Saturday night thing. If so, I hope your cooler called out sick.

004. Doc

January 4, 2019Fantastic fiction often asserts that forces awesome, alien, or profound enough to overwhelm our senses will be processed by our puny brains in ways we’re capable of processing instead. The erratic movements and sudden disappearances of UFOs are how we see extradimensional travel. Vast unspeakable intelligences present themselves to us as dragon-winged squid-gods. Fire and life incarnate themselves in a flaming bird shape and a costume color-scheme change.

But can it work in the other direction? When faced with the inexplicable, can our minds process it into something more human, not less?

The life of Dr. Elizabeth Clay in Road House can be divided into five phases. She meets our hero, Dalton, when he’s admitted to the hospital where she works for the treatment of a knife wound he incurs on early in his tenure at the Double Deuce. After telling him the cut will require nine staples, she rattles off a list of previous injuries from his medical files, which he carries around with him. (“Saves time.”) She offers him a local anesthetic, which he refuses. (“Pain don’t hurt.”) She notes that his medical files say he graduated from NYU, where, he tells her, he studied philosophy. (“Man’s search for faith, that sort of shit.”) Given the damage that’s been done to his body, she facetiously asks him if he’s ever won a fight. (“Nobody ever wins a fight.”) Furthering one of the film’s recurring jokes, she says that she figured someone in his line of work would be bigger. (“Gee, I’ve never heard that before.”) Perhaps because nearly everything he says would look good as a back tattoo, she accepts his offer to take her out for coffee in the middle of all this.

Next time we see the good doctor, she shows up at the Double Deuce for their date, in a dress that looks like something Billy Joel and his first love ordered a bottle of white, a bottle of red over. She arrives in time to watch him finish beating the tar out of several of Brad Wesley’s goons alongside his fellow bouncers. During their date she brutally negs him for getting paid to hurt people, and for acting like a Nice Guy when he clearly isn’t. Perhaps impressed by how he tosses money on the counter of the diner where they’re eating so that the grumpy manager will allow a falling-down-drunk old man to sit there a while longer, or the good-natured way in which he reacts to discovering his enemies have rammed an entire stop sign through the windshield of his car, she gives him a chaste but heartfelt kiss goodnight before leaving. (He gives her the same little salute he gave the Second Car Salesman of Jasper, Missouri as she drives off.)

She meets up with him at the Double Deuce again a few scenes later, by which point Dalton has pretty much single-handedly reversed the place’s fortunes, which you can tell because the bartenders are wearing uniforms and there’s no longer any chicken wire around the bandstand to protect the performers from the audience. They go back to his place. He turns on the radio and, after they both reject Bullet’s “I Sold My Soul to Rock n’ Roll,” settles on “These Arms of Mine” by Otis Redding. They exchange five or six sentences about her Uncle Red, who raised her after the death of her parents, and her failed marriage. Then they have sex; he’s inside her, standing up, before they so much as kiss. She laughs while they fuck, like she’s in on the joke. Later that night they fuck again, on the roof, in full view of Brad Wesley, who lives across the water, and whose house she looked at ruefully shortly after arriving at Dalton’s apartment because he was the person she had the failed marriage to. (Though their relationship is confirmed, the actual fact that they were married is never stated outright, but the vacuum-sealed logic of the film allows no other possibility; there’s not enough room in anyone’s life for two major former disastrous love interests.)

When Dalton’s mentor Wade Garrett comes into town to help him in his battle against Wesley—Elizabeth has become a focal point in that grudge, and in Dalton’s desire to stay in town and take Wesley down rather than simply picking up stakes and moving on when things get ugly, as Wade advises—the two men and Elizabeth spend the night on the town, drinking beers and swapping stories about their old antics and injuries (the two are inseparable), which at one point involves Wade unbuttoning his jeans and revealing the dark thatch of his pubic hair to show her a scar on his hip that a woman gave him. They pull an all-nighter, during which Wade and Elizabeth dance in a diner (not the previous diner, nor the place they spent the night talking and drinking in, nor the Double Deuce, but a fourth dive altogether) and he comes on to her pretty heavily, with just enough plausible deniability that everyone can play it off with a smile. The sexual tension between all three is just insane, though it’s cut short by the start of the work day. (“Don’t mean to bust up the party, but my shift starts in a couple of hours—thought I’d go home, get some sleep,” says the trauma surgeon after spending the past five or six hours drinking.)

Elizabeth’s final emotional beat in the film is as the unhappy go-between in the Dalton/Wesley feud. She chastises Brad (she’s the only person who calls him that) for destroying Strodenmire Ford with a monster truck, and warns Dalton that if he’s trying to save the townsfolk from Wesley, “Who’s gonna save them from you?” Actor Kelly Lynch’s commitment to this line, which she shrieks at the top of her lungs, is so total that when Wesley’s lead goon Jimmy blows up the shack where Dalton’s landlord Emmet lives the next moment, at first it seems like she Carrie‘d the place. When Dalton kills Jimmy by ripping his throat out with his bare hands, she checks to make sure the man is dead, then leaves, horrified, and refuses to leave town with Dalton when he tries to convince her to do so at the hospital the next day. For some reason she goes to Brad Wesley’s house during the middle of Dalton’s killcrazy rampage through his army of goons; her arrival prompts Dalton to not tear Wesley’s throat out, which gives Wesley a chance to go for a gun to finish Dalton off, but fortunately four old men show up with shotguns and Sonny Corleone the shit out of the guy.

After she watches her ex-husband die during an attempt to kill her current boyfriend-ish guy, the doctor and Dalton are reunited and skinny-dip in front of his landlord Emmet happily ever after.

Every time I watch Road House I grow more and more fond of the Doc. And why wouldn’t you? She’s the smartest and most together person we meet, having one of the few jobs anyone holds outside of the automotive, alcohol, or beating-people-up industries. She has a good head on her shoulders regarding the lunacy of Dalton and Wesley’s blood feud, which has involved the total destruction of at least three buildings in town and the severe injury of dozens of human beings even before people start dropping like flies. Removed from the French braid she wears it in for work, her hair does this cool thing where it sticks out on the sides like an old Barbie doll. She’s one of the few human beings who could get bare-ass naked next to in-his-prime Patrick Swayze and hold their own.

However, she also accepts a date from a masochist who’s constantly getting his ass kicked, which she knows because she meets him while stapling his latest knife wound. She holds his job in open contempt and mocks the idea that he’s a force for good in town even when they’re getting along and used to be married to his arch-enemy, whose murder during the process of his attempted murder of Dalton she witnesses before settling down with Dalton for good. She goes into work at a hospital on two hours of sleep after spending the small hours pounding Miller High Lifes. Even by the standards of Road House, a film about famous bouncers, her behavior is hard to recognize as that of a normal human person.

Yet when I think about her, it’s always in terms of “Wow, way to put him in his place,” or “power move,” or “wearing that dress takes guts,” or “fucking before kissing, right on, this is a person who knows what she wants,” or “she must really love her uncle to hitch her star to Jasper, Missouri’s wagon on his account, I bet he was a great dad to her” or “she patches up Dalton’s knife wound but the next time we see her at work she’s looking at x-rays of someone’s colon, what’s her medical specialty,” or “she could absolutely talk Dalton into making out with Wade in front of her and she knows it, and just sits with it because knowing it is all the satisfaction she needs,” or “I wonder what she saw in Brad Wesley,” or “I bet she went to an Ivy League medical school because she’s just a little condescending when she talks about Dalton going to NYU.” In other words, things you might think about a normal human person, and a very interesting one at that. Confronted with Road House, the mind transmutes chaos into character.

001. Fame

January 1, 2019 Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

So that tells you something about the kind of film Road House is: It respects the people who beat up people who beat up other people in bars so much that it affords them significant renown. Other men will fly across the country and offer these men hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for their services. Barfolk, for want of a better term, whisper their names in reverent awe. In the land of the blockheaded, the two-fisted man is king.

Because their reputations precede them, or because to invoke them inaugurates the ritually contracted cycle of redemptive violence for which they’ve been hired, the bouncers of Road House are reluctant to share their names.

“You got a name?” asks Carrie Ann, waitress at the Double Deuce, the ultraviolent Missouri honky-tonk at the heart of the story. “Yeah,” answers our hero.

“What’s your name, buddy?” asks Pat, the Double Deuce’s thieving failnephew bartender, who is played by John Doe of Los Angles punk institution X. “Coffee, black,” responds our hero.

When he conducts his first official bouncing during his tenure at the Double Deuce by smashing the face of a man with a switchblade and a Hawaiian shirt through a table adjacent to the one on which this man’s girlfriend has been dancing and thus lowering the overall atmosphere of class in the establishment, it falls to our hero’s blind white blues-playing guitarist friend Jeff Healey (appearing as himself) to reveal his identity to the amazed, and in several cases visibly aroused, patrons.

“The name,” he says, “is Dalton.”

Dalton is by this point in the film known to the Double Deuce’s staff, over whom he’s been given absolute authority by the bar’s bizarre owner Frank Tilghman. “What he says? Goes,” Tilghman tells his employees.

“It’s my way or the highway,” Dalton concurs.

The first person to learn his identity other than Tilghman himself is Carrie Ann, who powers through our hero’s extremely badass rebuff as described above and gets him to name himself, the way Superman tricks his gnomish extradimensional enemy Mr. Mxyzptlk into saying his own name backwards to eliminate him. (Carrie Ann has no such goal, of course; it is perhaps for this reason that she is rewarded later in the film with a glimpse of our hero in the nude. to which she reacts with slackjawed lust so powerful, courtesy of actor Kathleen Wilhoite, that it all but glows with its own internal erotic energy.)

“Shit,” Carrie Ann says when Dalton reveals himself. “I heard a’ you!”

The news spreads like wildfire through the waitstaff, bartenders, and bouncers already in the Double Deuce’s employ, none of whom need its import explained to them. Like I said, a famous bouncer’s reputation precedes him. One man has heard he ripped a guy’s throat out with his bare hands. Another has heard he has balls big enough to come in a dump truck. “Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name,” runs the song from another artifact of Eighties bar culture. Dalton can go anywhere.

Which gives us some indication of his exact level of fame. No one at the Double Deuce recognizes him on sight, which means he’s not so famous that his face alone writes his ticket for him. However, the moment he says “Dalton” in response to Carrie Ann’s query, she immediately assumes he is the Dalton famous for being a bouncer, and not any of the other myriad possible Daltons in the world—B. the bookseller, for example. It’s as if she asked a woman who was new to the Double Deuce for her name, and that woman replied “Gaga.” Only one person leaps to mind.

This separates our hero from his hero. “Wade Garrett’s the best,” Dalton tells Tilghman when the Missouri restaurateur says he’s heard he, Dalton, is the best. “Wade Garrett’s getting old,” Tilghman replies. But age has not dimmed his starpower. Arguably, age is responsible for it. The longer he’s been out there, bouncing and cooling, the more time the dive-bar demimonde has had to put a face to the name.

The face belongs to Sam Elliott, who in this film has long greasy hair, tight black jeans, five o’clock shadow that creeps up his face nearly to his eyes, and a grizzled sexuality that wafts from the screen like a musk. When he arrives at the Double Deuce to help his one-time protégé Dalton defend the establishment against the depredations of Brad Wesley, a local business tycoon and J.C. Penney franchisee played by Ben Gazzara (The Killing of a Chinese Bookie), no one asks his name, because no one needs to. Practically the entire staff stares at him with the wide eyes of children in a film directed by Chris Columbus when he limps bowleggedly into the place looking for his mijo.

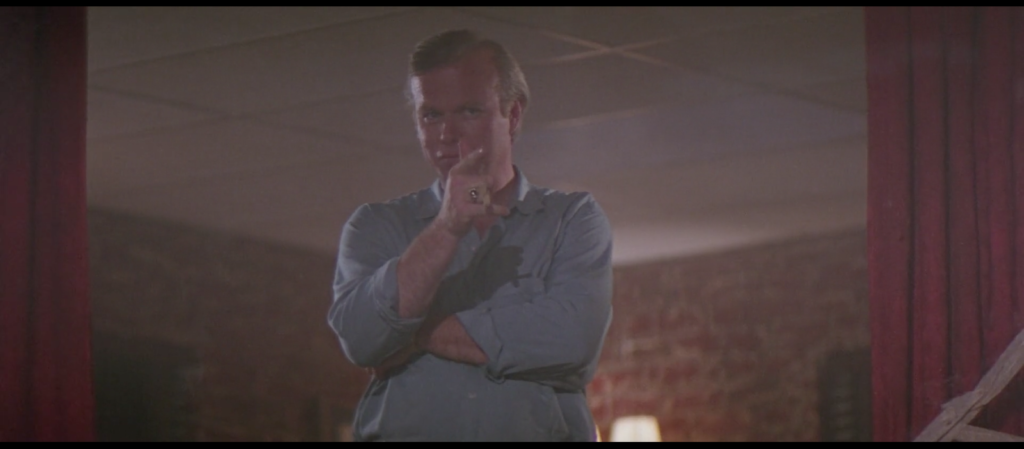

Grinning slyly, his eyes twinkling with a sinister delight that seems to be actor Kevin Tighe’s natural mien and has no basis within the character itself, Tilghman looks at this man and says, “I know you.”

Wade Garrett, it can be concluded, has achieved a level of fame so total that even people steeped enough in bouncer culture to know Dalton by name know him by sight. Michael Jordan fame. Michael Jackson fame. Santa Claus fame. Wade Garrett is the best, Dalton tells us. And when Dalton speaks, we would do well listen. It’s his way or the highway. What he says? Goes.

Directed by Rowdy Herrington, written by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin (Academy Award winner, Wag the Dog), released in 1989, directed by Rowdy Herrington (the name bears repeating), and starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara, and an assortment of people with anywhere between one to six lines of dialogue all of whom I adore completely, Road House is one of my favorite movies ever made. I like to talk about it. I hope you’ll like to listen.