Posts Tagged ‘dalton’

055. Rise and shine

February 24, 2019After a long night of breaking tables with people’s faces, firing bouncers for fucking teenagers in the storeroom, making Frank Tilghman fire Brad Wesley’s nephew (and I think it’s safe to say his own lover) Pat McGurn, and reading Jim Harrison novels while Wesley and his goons have a topless pool party across the water, Dalton likes to get out of bed hungover without drinking a drop the night before and fully nude in front of his co-worker Carrie Ann, light a cigarette before he finishes buttoning the fly of his jeans, and do some light stretches without even taking the lit cig out of his mouth as she presents him with coffee and a jelly donut or a danish or something. That’s just who he is. That’s just how he (jelly)rolls. The whole little morning ritual we see when Carrie Ann pays him her erotically charged visit is a delight precisely because of the incoherent portrait it paints of this man. He’s constantly smoking even when he’s exercising but he turns up his nose at junk food. His entire method of bouncing depends upon everyone reading everyone else for the slightest cues and clues but he walks around bareassed in front of a woman over whom he has hiring and firing authority, who’s there delivering him food out of the goodness of her own heart. He’s a huge nerd who was up all night reading a book, to the point where he frowns upon some relatively wholesome sex-comedy shenanigans over at Wesley’s place, but when he wakes up it’s like he’s coming off a three-day bender. If you sat and tried to depict the contradictory demands of ideal masculinity—stoic yet vulnerable, wise yet monosyllabic, sexy yet oblivious to his own sexiness, abusing the body he treats as a temple—I don’t know if you could come up with a better illustration than a shirtless Dalton doing his morning stretches while smoking like Dan Aykroyd in Ghostbusters while wearing pants he hasn’t quite finished putting on.

054. The Ballad of Pat & Tilghman

February 23, 2019Standing in the bar down in Jasper

Sweeping up the eyeballs for thrills

My bartender’s Pat

Hey, at least I have that

Until when Dalton said he’s skimming the till

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Finally found myself with some money

Thought I’d fix the place up just right

Dalton helped me to learn

That my man Pat McGurn

Costs me about a hundred-fifty a night

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Pat McGurn’s the son of Brad’s only sister

Canning him’ll take me some nerve

I may own the bar

That only takes me so far

Cuz Mr. Wesley owns the liquor I serve

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Wesley takes my money almost every day

“Jasper Improvement Society”

It’s his town he said

Oh boy when he’s dead

The killers will be four men who are old (Tink)

“Take the train, consider it severance”

Pat looks at me raising his brow

Incredulous Pat:

“I didn’t hear you say that”

I stammer “Well, I’m sayin’ it now”

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

Pat McGurn’s my headcanon lover

Firing him makes me start to pout

His voice is a purr

When he asks “are you sure”

Takes all I have to whisper “get out”

Christ, you know it ain’t easy

You know how hard it can be

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

A man named Brad Wesley

He’s gonna crucify me

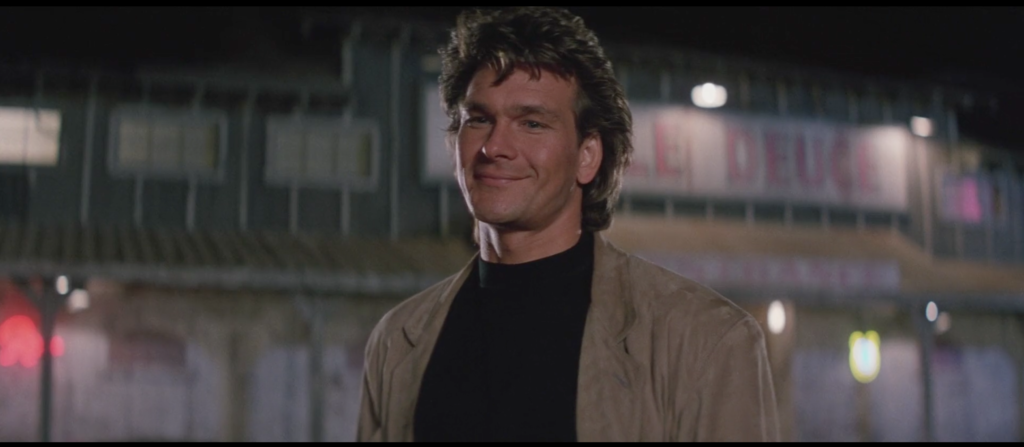

053. Why We Fight

February 22, 2019“This has been, without question, one of the worst weeks of my life, but one man offers succor.” I tweeted this with the above picture a few minutes ago, as I sat down to write today’s Road House essay. I knew exactly what I was going to write about, too. I knew the scene, knew the moment, knew the angle, knew how to flesh it out. It’s one of the ideas that made me want to start this project in the first place. So I’ll get to it, probably soon, and I’ll enjoy it and hopefully you’ll enjoy it as well. But wasn’t until I opened up WordPress in a new tab that I realized the thing I posted on twitter before writing today’s Road House essay is today’s Road House essay.

I’m not going to talk about the week I’ve had, or why it’s been so bad, bad enough that as I type this I am home alone with my stepson instead of out with my partner and our friends because we were supposed to go to an all-sad-songs karaoke party together and I am too sad for Sad Song Karaoke. It’s not really my story to tell anyway. I’ll tell you what is, though: Road House. I don’t think I ever fully understood the concept of “comfort viewing” until Road House came into my life. I don’t think there’s any other film like Road House out there. Viewed communally, which is how I watched it the first time, it’s joy, an invitation to participate in the kind of drunken cinematic mental and verbal horseplay that always makes me think of Ozzy Osbourne saying “eat shit and bark at the moon.” It’s a bark at the moon movie. Viewed in a more intimate setting, with just one or two people who’ve never seen it before, it’s the closest thing to taking a child to an amusement park and seeing a world of delight open up before their eyes, seeing it through their eyes, that I’ve ever found this side taking my daughter to Coney Island for the first time. I have yet to screen this movie for any first-timer who didn’t fall in love with it immediately. Viewed with the person I love it feels like a comfortable couch, a long conversation punctuated by bursts of laughter, the easy romantic camaraderie of talking lightly while getting dressed after sex, a car ride soundtracked by songs we both adore, a hit of Gorilla Glue and a sip of Noah’s Mill, a shared secret, a private joke, a glance that means something to us and no one else. Everyone has these things, but no one has our things; that’s how Road House works. Returned to in isolation day after day, night after night, it has proven to be an inexhaustible source of pleasure and inspiration. This dumbass brilliant movie about a famous bouncer’s duel to the death with an unhinged 7-Eleven franchisee and his army of hapless meatheads for the soul of a town populated exclusively by beautiful blonde women, howling yahoos, and the living embodiments of old man smell is a case study in the rewards of close reading, the powers and boundaries of genre and style, the maxim held close to my heart that the energy of every character in any story can be kinetic rather than potential. At the heart of it all is Dalton, warrior, philosopher, guru, hero, lover, killer, smoker, fighter, fatherless son, living breathing erasure of class distinctions, poet of one-liners and vulgarities, preternaturally calm, childishly petulant, soul of a Blake and body of a Baryshnikov in a world that has made him a gladiator, a prophet and a pusher, partly truth partly fiction, a walking contradiction, played by a beautiful man who once said of the cancer that would go on to kill him “I’m in great condition. I’m a cowboy. I’m a dancer. I’ll beat this.” Every punch in the face, every grotesque insult, every dumb joke, every inexplicable line reading, every grin on Ben Gazzara’s face, every sauntering step Sam Elliott takes, every white-blues song on the soundtrack, every remarkable mutant in the cast, every glimpse of Dalton’s face and hair and chest and ass and credo feels to me to have sprung from the heart of the man that said those words—the cowboy and the dancer who raged against the dying of the light. This has been, without question, one of the worst weeks of my life, but one man offers succor.

052. Boot knife gleam

February 21, 2019

They added a gleam effect to the knife in the boot on the leg of the goon who tries to high-kick Dalton in the head with his knife-mounted boot. Just in case, you know. Even with the closeup—an eyeline match cut from Dalton and his Padawan learner Jack to the boot and then back again (Dalton: “Right boot.” [pause for boot] Jack: “Got it.”)—the audience could have missed it, primarily because even for the kinds of people who might want to watch Road House boot-mounted knives are not the kind of thing you’re trained to spot in the wild. Can’t be too careful, really.

No, really. Let’s review. Never underestimate your opponent. The opponent here is the audience’s inability to recognize a knife sticking out of a Knife Nerd’s shitkicker. Expect the unexpected. You wouldn’t expect someone to miss the knife when it’s one of three things on screen, the other two being the boot and the jeans covering the leg part of the boot, would you? Take it outside. Step beyond the boundaries of yourself and see things through the eyes of others. Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary. The trouble here started when Brad Wesley, outside the bar, ordered this man to go inside for the express purpose of necessitating violence. Be nice. Dalton’s simply points out the location of the weapon to Jack rather than raising holy hell, a first move echoed when he amasses his bouncers, approaches the boot knife goon with a smile, and simply says the bar is closed. Until it’s time to not be nice. The arrival of the boot knife is the big hand reaching Not Nice O’Clock.

That gleam is not just the light reflected off some jackass’s dopey weapon. It’s Dalton’s bouncer-sense made visible.

051. Tableau III (Nipple to Nipple)

February 20, 2019Here in the Double Deuce, after Dalton’s arrival, prior to The Agreement and the subsequent bar-destroying brawl, things are proceeding as one assumes they always proceed. Denise, Jasper’s sole indication that there is a non-Jasper culture out there to which one can aspire, glides up to the bar to ask Pat McGurn (John Doe, cofounder of X, lest we forget) for a “vodka rocks.” Enter the Barfly, and this is actually how he’s credited, “Barfly,” played by Frank Noon. In a film teeming with barflies he is selected as the representative specimen. This absolute slob, I mean maybe the most gormless motherfucker in the whole film, this asshole sidles up to her and says “Hey, Vodka Rocks, what do you say you and me get nipple to nipple.” I hesitate to call this pickup line a euphemism, because it’s actually much more vulgar than describing the sex act outright. Getting nipple to nipple is a phrase that can only make one feel bad about having sex, or wanting to have sex, or being capable of having sex, or being part of a species that propagates itself by having sex. It embarrasses me anew every time I hear it. Goof coming out of his well armed with his quip to slutshame mankind. Point is it’s not happening for this turkey. Denise looks down in contempt, unconsciously mirroring the way Dalton, whose hair is only slightly less magnificent than hers, looks down in disapproval. Then she looks up and, this being Road House, shoots the guy down in the strangest possible way. “I can do that without you,” she says, before turning away and giving Dalton an appreciative once-over (more like a thrice-over actually, she is hot to trot for our hero) in the process. The reasonable interpretation of this rejoinder is that Denise can somehow aim her breasts at one another so that her nipples can touch, a pincer movement if you will. I choose to believe she thought fast and decided to shoot this goofy down by saying something even weirder than he did. Either way, and I hope you’re sitting down for this, he does not take rejection well. See Morgan back there? He’d been leaning on the bar in the background unseen until the dirtball mooselipped chickendick made a pass at Denise. (Do people make passes at other people anymore? When I was a kid Three’s Company and The Golden Girls had me believing that’s all anyone did as an adult. “He made a pass at me” is something I’ve never heard a human being say outside of a multi-camera sitcom. Anyway) The moment after “nipple to nipple” dribbles out of his mouth, Morgan pops into the frame from behind, like a fucking jack-in-the-box. It’s one of my favorite little moments of abject stupidity in the movie. On his worst day in the ring, Terry Funk couldn’t oversell a bump half as hard as he oversells Morgan overhearing someone hit on his secret boss’s girlfriend and getting mad about it. Of course Morgan is always mad. He’s an orneriness elemental. And he puts it to good use when Mr. Nipple angrily grabs Denise by the shoulder. Morgan grabs him by the shoulder, punches him in the gut, and tosses him into a table full of patrons, spilling him and them and the table and the drinks on it and several bystanders to the ground in the process. Why this doesn’t lead to an apocalyptic bar-wide battle royale is beyond me given that The Agreement ends in a nearly identical fashion, but at the very least it gives Dalton, serene and detached, an eyefull of Morgan’s modus operandi. This is clearly a bouncer who will need to be bounced. So! Beautiful, slightly weird woman. Ugly, very weird man. Angry, very angry bouncer. Knocked-over tables. Knocked-over patrons. Pat McGurn. The malign influence of Brad Wesley behind it all. Dalton has just gotten nipple to nipple with the Double Deuce. It’s not pretty.

050. The Third Rule

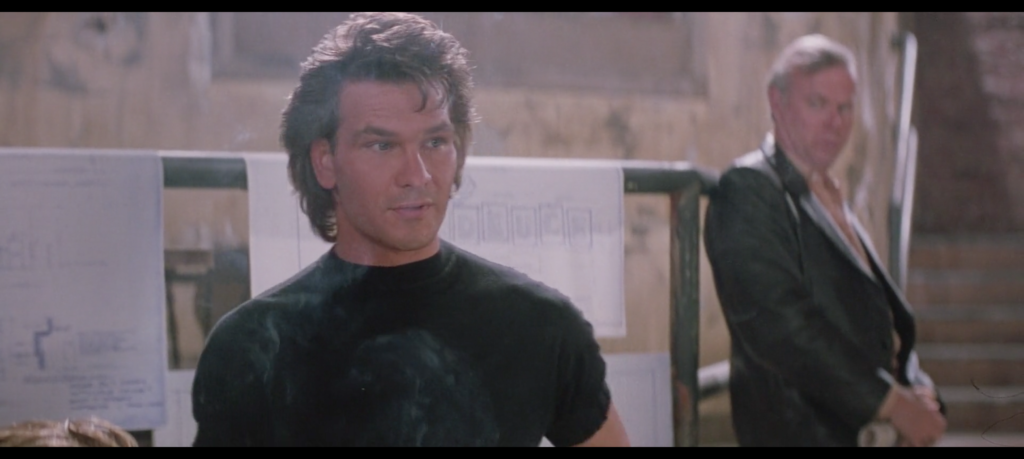

February 19, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This is the third.

3. Be nice.

The three simple rules for bouncing my Jasper road house all contain and account for their own direct contradiction. More than that, they depend on the aspirant’s ability to formulate that contradiction to be fully understood. Thus “Never underestimate your opponent; expect the unexpected” conveys both that chance will always break in the enemy’s favor and that a true brother bouncer—the unmentioned ally in a rule nominally covering the adversary—leaves nothing to chance at all. “Take it outside; never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary” is as much about one’s headspace as it is about one’s physical space, such that participation in a fight that takes place within the building is a requisite condition for obeying the rule in the first place. Even Dalton’s prefatory statement “All you have to do is follow three simple rules” is best thought of through the formulation of the philosopher Linda Richman: They are neither three nor simple nor rules nor followed.

So. The Third Rule. It is the shortest rule, and it requires the most explanation. It is the least practically minded rule, and it is illustrated with the most practical applications. It is a rule about being kind to others, on the surface at least, and it is the rule greeted—and at times delivered—with the most open incredulity, even hostility.

All this is necessary. One must see the complicated clockwork mechanism behind the simplest maxim. One must learn that on the Dalton Path, all philosophy is applied philosophy. One must be goaded into anger to understand the nature and value of its opposite. These things the Third Rule anticipates, mandates, births into being. This simplest of the three simple rules is alone in meriting a fuller and more complex reformulation from the Giver of the Rules, a new testament to unlock the old. It is the Great Commandment. It is not come to destroy, but to fulfil.

3. Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.

to be continued

049. Jimmy, or The Laugh

February 18, 2019It’s not all fun and games. No, it’s not all fun and games. We joke here at Pain Don’t Hurt, we laugh here, because Road House is a fun and often (nearly always) funny movie. But the Dalton Path leads inexorably toward darker days and nights.

This is Jimmy, Brad Wesley’s right-hand man, chief enforcer, and bastard son. (Non-canonically.) We’ve met him before during the nearly fifty days I’ve been writing about Road House, but he has remained a liminal presence, his dark eyes and blue denim looming in the background like a pale man at a party in a David Lynch film. He accompanies Wesley to Red Webster’s store for their weekly payout but doesn’t say a word. He drives Karpis (unnamed handsome man, in the parlance of the film itself) to fuck the store up later on but never gets out of the car. He laughs as Wesley beats O’Connor for bleeding too much but never throws a punch. He scoffs at Dalton and the Doc as he and Ketchum (the other unnamed goon) spy on them but doesn’t make a move.

It’s at the precise moment when Jimmy is finally set loose, battling Wade Garrett and the entire Dalton-led bouncing staff of the Double Deuce after Dalton cruelly shuts down Denise’s Wesley-approved antagonistic striptease (?!), that things go bad.

Brad Wesley, who moves through life grinning wryly at virtually everyone and everything he sees, has taught his boys well. All of them, even Tinker, have learned to laugh at the misfortune of others, and at nothing else. But Jimmy is Brad’s best boy, and his is the deepest laugh, the fullest laugh, the loudest, the longest—and the last.

Jimmy emits this piercing and preposterous peal—the supervillain laugh to end them all—after blowing up the shack where Dalton’s landlord Emmett lives (and, judging from the size of the explosion, cooks meth) in the middle of the night. So delighted is he by the night’s mean work that he actually stops his getaway motorcycle to look back, take in the extent of what he has done, and enjoy the moment to its fullest. He laughs like a man not acquainted with the concept in any context where the smell of blood and cordite is not on the night wind.

In this moment, Jimmy exhausts the good humor of the Wesleyan Goons with one titanic cackle of pure, joyous malice. No longer are they the cocky cut-ups who run over car dealerships with monster trucks or get beat up in bars. From here on out they exist to kill. Jimmy inhales horseplay and exhales murder. And Dalton is the man who breathes that fire back in.

041. Breaking a table with a human face

February 10, 2019If you want a picture of the Double Deuce, imagine a table broken by a human face — for ever. I’ve been thinking about the way Dalton grabs the Hawaiian Shirt Knife Nerd who was willing to defend his girlfriend’s right to dance on a table literally to the death by the back of his head and smashes his face down into a second table so hard and so fast that the wood splinters cleanly in half a lot lately. It’s a terrifically intuitive and forceful bit of fight choreography, that certainly helps. It conveys Dalton’s efficiency of movement and his power at short range, key to making him seem like a physical threat when half the characters in the movie say “I thought you’d be bigger” to him at one point or another.

Crisp editing by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link (Die Hard, RoboCop, Predator, Commando, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Tombstone) sells the move, but not alone. As an actor, Patrick Swayze takes a heretofore unprecedented turn for the savage in this moment, scowling with fury we’d previously seen no trace of at all. As time passes we’ll see more and more of this look from him. (To the extent Dalton has a character arc it’s largely one long descent that begins at a moment we’ll discuss in detail later in this series and ends with five murders.) Dalton traffics primarily in a blend of the Western and Eastern forms of coolness; he’s gunslinger tough and martial-artsist enlightened. The audience needs to see what happens when he gets heated up, and how little normal men can do to stop him when it happens.

When does it happen? This is important as well. The scene that precedes the table incident is none other than the Giving of the Rules, in which Dalton lays out his credo for successful bouncing and cooling. “Never underestimate your opponent/expect the unexpected”? Check. Dalton chose to act in such a way that this guy was done before he even realized the fight had started. No surprises coming from that corner. “Take it outside/Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary”? Okay, sure, we’ll allow it. This bizarre little man drew a knife and threatened to murder a bouncer simply because he’d been asked to ask his girlfriend to stop climbing on the furniture. Sounds absolutely necessary to me. (And the Third Rule? Perhaps you know it already, perhaps you don’t. We will not be discussing it just yet. We will not discuss it…until it’s time to not not discuss it. Let’s just say that grabbing a human being by his hair and forcing his skull through a table sturdy enough to dance on speaks volumes on the Third Rule’s contents.)

What happens immediately afterwards? Everyone in the bar gazes and gasps in awe. People nearly move in slow motion, they’re so stunned by his prowess. Even the woman whose boyfriend has just been given some kind of concussion gingerly takes Dalton’s hand to be led down off the dancing table, and looks back over her shoulder at him on her way out of the bar. This is a man worth turning into a pillar of salt for. “The name…is Dalton,” Cody announces from the stage (through the chickenwire), after being filled in by his sighted bassist as to the nature of the hubbub—like a talk-show host announcing a guest, or the lead singer introducing the band. People in the Road House Universe absolutely adore people who break tables with other people’s faces.

Finally, there’s the savagery of the act itself. Powerful agent to the uninitiated. WA-BAM! He broke a table with a guy’s face! Didn’t even give him a chance! If you’re a first-timer and you reach this moment, any fears you may have had as to whether the first big barfight was the last time you’d see anything that gratuitously, moronically violent, this lays your fears to rest. You ain’t seen nothing yet.

040. The Second Rule

February 9, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This is the second.

2. Take it outside. Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary.

A bouncer less wise than Dalton would think Rule 2 begins and ends right here. How much more could there possibly be to this purely practical commandment? Your job is to maintain a convivial atmosphere for the patrons of your establishment by keeping the bad element at bay. You can’t do this if you’re beating the shit out of a guy on the dance floor. Ergo, you either force or lure your opponent out of the bar—your ultimate goal at any rate—before engaging in fisticuffs. What else is there?

What else indeed. As you can no doubt imagine, many, many violent incidents occur at the Double Deuce between this speech and the end of the movie. Dalton and his men take it outside a grand total of once during that time. Dalton in fact grabs a guy by the back of the head and smashes his face through a table this very night. What conclusion can we draw from this?

What we have here is another “If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig” situation.

Let’s start with the assumption that Dalton, as evidenced by his own actions, must intend this rule to have some larger meaning beyond its (eminently sensible) practical application regarding the bouncer’s ideal field of battle. I would suggest that we look to the Third Rule for the key to unlock this mystery. A thorough examination of that rule must wait for another day, but for now suffice it to say “It’s nothing personal” is a central component.

Could it be the case that in commanding the staff of the Double Deuce to “take it outside” when the moment of truth arrives, what Dalton really means is to step outside themselves? Those who follow the Dalton Path must see themselves as parts of a greater whole. They are but tools in the hands of the Cooler; does the hammer hate the nail? They are the immune system of the bar-organism; does the white blood cell hate the infection in the wound? The bouncer is the agent of Gemeinschaft. Proper function necessitates depersonalization so that the wider view may come into focus.

Now let us go further. What is it to “start something inside the bar”? We have already learned that many of the forces that threaten the Double Deuce are not conflicts that arise organically between patrons, but deliberate infiltration and provocation directed by an outside agent: Brad Wesley. Wesley himself is merely a symptom of larger societal crises: capitalism generally, the tyranny of the small business owner specifically, toxic masculinity, and even, as we will see when we enter his Trophy Room, ecological destruction.

Moreover, let us not allow “conflicts that arise organically between patrons” to pass by unremarked upon. Dalton identifies the Double Deuce’s problematic clientele as “Forty-year-old adolescents, felons, power drinkers, and trustees of modern chemistry.” Cultural neoteny, the carceral state, alcoholism and addiction, and the role of business and government in fomenting all of the above: One need not absolve the meathead or the Knife Nerd of personal responsibility to correctly argue that they themselves are often victims of forces far beyond their control.

Now let us return to the Second Rule. “Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary,” says the man who will break a piece of the bar’s furniture in half with another human being’s face just a few short hours later. Who is he really addressing here, and what is he saying to them? Is he simply telling the bouncers (and waitstaff and bartenders and band members and the unknown entity in the brown jacket) to avoid throwing hands inside these four walls? Or is he employing paradox to demonstrate that nothing ever truly starts inside the bar—that while the Dalton Path offers a safe route through the bar for all who choose to walk it, it is a road without beginning or end?

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms. (Ephesians 6:12)

039. Biker Gang

February 8, 2019The very first people to give Dalton shit upon his arrival in Jasper aren’t Brad Wesley and his goons. They aren’t the corrupt members of the Double Deuce’s staff. They aren’t even Knife Nerds or other random ne’er-do-wells among the club’s clientele. They’re a biker gang, in the Double Deuce’s parking lot. “Mer-SAY-dees!” they whoop it up as Dalton parks his luxury work of German engineering in the unpaved unloading zone for the town’s worst element, glaring at him all the while. “Hey hotshot! What’s wrong with Dee-troit cars?” Dalton simply stares back at them and their bikes and their very cool ’80s bad-guy car, tosses away his cigarette, and goes about his business. You and I are left with more to ponder.

At first blush it’s just a bit of color, a way to convey that the Double Deuce is a rough and tumble environment before you so much as step through the doors, in the same way that watching Morgan the evil bouncer toss a guy through those doors a few seconds later (“Don’t come back, peckerhead!”) lets you know what you’re in for once you set foot inside. What makes it a uniquely Road House bit of color how none of it has the slightest relevance at any point in the future, and how no element of it is ever heard from again.

Are biker gangs a threat Dalton will face in his quest to clean up the Double Deuce, and eventually the entire town of Jasper? No. Not even a little bit, in fact. The problems all stem from Brad Wesley, the Fotomat King, and his merry band of assholes. This is Road House, not The Road Warrior. Though Dalton and Brad Wesley could well be the Mad Max and Lord Humungus of the post-guzzoline Missouri wastelands should it come to that, this is merely informed speculation.

Is there a slobs vs. snobs angle to the movie? Again, no. For one thing Dalton always stows away his fancy car and uses a ringer instead once he starts working, so he doesn’t even bring the Mercedes back to the Double Deuce, or anywhere else for that matter, until the end of the film. He doesn’t ostentatiously spend his money, or wow the local yokels with his citified ways, or even crow about his NYU philosophy degree to woo Dr. Elizabeth Clay. What’s wrong with Dee-troit cars? Nothing, as far as he’s concerned. (This is a question better directed at Brad Wesley.)

Maybe these guys play a role in the ensuing all-hands-on-deck barfight, the movie’s first? Once again, no. The instigators and all the primary combatants are just the usual drunken shitbirds and meatheads. While it is true that one of the bikers miraculously appears inside as the Shirtless Man about twenty seconds later, this is down to Road House‘s charmingly free-form approach to continuity, rather than the idea that this guy somehow raced around to a back entrance, bared his chest, and started boogying down in the time it took Dalton to cross the parking lot and enter from the front. The Shirtless Man, at any rate, is a dancer, not a fighter.

But in their own pointless way, the bikers illustrate the importance of Dalton’s First Rule: “Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected.” Your enemies could look like anyone, come from anywhere, and attack at any time, even if their offense consists solely of “Buy American” jingoism. A cooler of Dalton’s experience and skill would have devised a plan for combatting these creeps within seconds, and likely kept it filed away throughout the course of the film, in case Brad Wesley ever hired them to run his clunker off the road, or prevent him from accessing one of Jasper’s many auto and auto-parts dealerships—or, less facetiously, bring the fight to grizzled old road dog Wade Garrett before he so much as parks his motorcycle. Indeed, one could argue that Dalton’s purchase of a beat-up car to replace his Mercedes was his way of defeating these opponents by depriving them of their casus belli. Victory is his before battle is joined.

033. Dead man

February 2, 2019When Dalton fires Morgan, the irascible bouncer played by pro wrestling legend Terry Funk, from the Double Deuce because he doesn’t have “the right temperament for the trade,” Morgan reacts as if determined to prove this was the right decision. “You asshole,” he growls. “What am I supposed to do?” “There’s always barber college,” Dalton deadpans in reply. The rest of the staff laugh at Morgan then, openly and for what I’d imagine is the first time. Dalton has defanged him.

Pointing his finger in Dalton’s face, Morgan delivers his farewell prediction: “You’re a dead man.” He nearly smacks his severance check out of Tilghman’s hand as he grabs it, then storms away.

Road House fans—Roadies—enjoy this interaction a great deal. It’s at least partially obvious why: How often do you get to see Patrick Swayze (Dirty Dancing) and Terry Funk (Halloween Havoc ‘89) tread the boards together? But it’s Funk’s innovative line readings that make this a standout scene.

He previews the direction he’s headed when he calls Dalton an asshole, which he pronounces “asshole,” emphasis very much on the second syllable and, one assumes, that particular aspect of the anatomy. Two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response, right? For Morgan—and he’s not the only person in the film to pronounce the word in this way—”hole” is the lead noun, not “ass.” In his eyes, Dalton is less the cheeks than the evacuating void between.

Still, this might have escaped notice were it not for the coup de grace: not “You’re a dead man,” as every other person in the history of the English language has pronounced it, but “You’re a dead man.” Here, the rationale is a bit harder to parse. Surely no matter what spin you put on this, dead is the most important, and insulting, aspect of the phrase, right? Dalton already knows he’s a man. Dead is the newsworthy part. And in making himself the bearer of this bad news, Morgan is issuing a threat. (This is all obvious, I know, but we’re being methodical.)

So why emphasize “man”? Not to praise Dalton, that’s for sure, despite the rubric established by asshole. He’s putting man front and center in the Shakespearean, “What a piece of work is” way. If we think of Dalton as a man, a human, we imagine all that entails: his infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood; his need to breathe, eat, drink, sleep, excrete; his social and biological drives to form community and find a mate; his hopes and fears and lusts; his prodigious skill and significant renown as a bouncer-philosopher; his future in all its possibility and inevitability. One pissed-off ex-coworker later and this could all be gone, a man reduced to meat and thence to nothing at all. In his own dimwitted way, from a brain that processes only rage and schadenfreude, Morgan is driving home what Dalton stands to lose, and what he plans to take away.

031. The First Rule

January 31, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This is the first.

1. Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected.

To the uninitiated, Rule One sounds like it ought to be Rules One and Two. The first part dictates that one cannot take victory for granted no matter the look of the foe, wisdom borne out time and time again throughout the film. Old men prove to be exceptionally capable fighters. Heavy men move at speeds men half their size can’t match. And as the Knife Nerds amply demonstrate, even the most rat-faced and weaselly goons can carry death in their denim. You underestimate these men at your peril. Assume anyone you face in open combat, even the bleeders and the sister-sons, can and will kill you if given the chance.

Expecting the unexpected is a different matter, or so it seems at first glance. Sometimes that means anticipating that a would-be assassin has a boot-mounted knife, or that a business dispute will be settled with a monster truck, certainly. But the unexpected could also be advantageous, could it not?

Not for the purposes of Rule One, no. The combination of these two diktats is not arbitrary. By wedding the latter to the former, Dalton suggests that the unexpected always breaks in favor of your opponent: a bootblade stabbing at a human face, for ever. The bouncer must accept this.

But the inverse is also true. If never underestimating your opponent necessarily and coterminously entails expecting the unexpected, it follows that a rational assessment of your allies deems them perfectly reliable. You don’t need to wonder whether your fellow bouncers can help you. You can bank on it. They will never disadvantage you in unexpected ways like your enemies might. Your comrades will be there and be true. You can expect it. “Watch my back and each others’,” Dalton says near the conclusion of the Giving of the Rules. But with the First Rule, he’s said it already.

It’s a bit of an “If you think this sentence is confusing, change one pig” situation, isn’t it: For bouncers to be perfected, they must follow Dalton’s three simple rules, the first of which takes their preexisting perfection for granted. But simply by turning the First Rule around in their minds the bouncers of the Double Deuce are that much further along the Dalton Path. They begin thinking every enemy with the wary respect you show a large animal or an operating piece of heavy machinery. They envision scenarios that will surprise and shock them, and thus begin to take those surprises and shocks in stride. In so doing they become people who are unsurprising, consistent, dependable, stalwart—each man a hidden blade in the boot that is the bouncer corps, expertly wielded by the cooler’s outstretched leg, working in concert against all the goons that were or are or will be.

028. Lebowski (I): Windshields

January 28, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a grizzled gray-haired man with a molasses drawl played by Sam Elliott dispenses wisdom to a practitioner of tai chi who finds himself at odds with a rich, sleazy business magnate with a personal goon squad played by Ben Gazzara. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film about same.

We will be revisiting the Road House/Lebowski Cinematic Universe. Boy, will we! But for now let’s focus on what I like to call The Windshield Shots. In Road House, Wade Garrett has just arrived in Jasper, Missouri to lend a hand to his old running buddy Dalton as the latter wages an increasingly vicious war with Brad Wesley, the film’s Gazzara. After rescuing his ass from a four-on-one beatdown—seriously, they’re just holding him in place and punching him in the gut like he’s a human heavy bag when Wade finally shows up to save the day—Wade goes for a drive in the passenger seat of Dalton’s car, the abuse of which by the angry patrons of the Double Deuce is a running gag, one that runs too far by any reasonable standard in fact. For that reason, riding shotgun puts Wade in an unenviable position.

But look at Wade here. He’s tickled pink! I assume he likes the feel of the wind through his magnificent head of hair, but it’s more than that. We will see, time and time again, how his most dangerous and dirty exploits amuse him, and how the same is true of Dalton’s. Riding through Jasper with a gigantic hole of shattered glass in front of him reassures him that it’s business as usual for his treasured “mijo.” It’s a sign that Dalton’s pissing off all the right people. And since Wade is a firm believer in the cut-and-run strategy when shit gets too heavy, he’s no doubt aware that the car will not long outlive Dalton’s stay in town, however long that may be. “It seems to me you’d be a little more more…philosophical about it,” he says later (much later) that evening, about an entirely different matter. But that hole in the glass, framing his “Aw shit-hell kid, I’m in hog heaven” grin, is already our lens into the Wade Garrett Mindset. He looks at broken things and sees a chance to live a life defined more by parts than the whole they add up to. Moving from one sensation to the next, treating calamity as opportunity, riding the nightlanes, bound only to those who ride with him: That is Wade Garrett. All Dalton can do is grin and bear it. Currently, it is time to be nice.

The Lebowski triarchy is an entirely different matter. Put aside whatever this Windshield Shot does or doesn’t owe to its predecessor. (I certainly believe the Coen Brothers, who after all put Sam Elliott and Ben Gazzara in their movie about a pair of weirdos fending off some rich guys and some goons, had seen Road House, but it’s irrelevant.) Despite sharing the tonsorial sensibilities of Wade Garrett, the Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, is pointedly not enjoying this breezy night drive. There will be no next down for him to head to. His car is not something he can stand to sacrifice. The Dude does not abscond. The Dude abides. He’d prefer to abide with a windshield.

Walter Sobchak occupies the Wade position in the car, but again, the contrast is revealing. No smile for Walter, no “shyush, don’t this beat all” grin. Walter is a man who can never admit that things have not gone according to plan, that every eventuality has not been foreseen and warded against. If at the beginning of the evening he said they would swing by the In-N-Out Burger, then goddammit that’s what they’re doing. If, in the interim, they attempt to brace a teenage boy for money he didn’t steal, vandalize a car he didn’t buy, and antagonize the neighbor who is the real owner of the car until the Dude’s own vehicle winds up getting the worse of it…well, the In-N-Out’s still there, isn’t it? Then he’ll by god buy it and eat it. As he says elsewhere in the film, “I’m staying. I’m finishing my coffee. Enjoying my coffee.” Situation normal, et cetera et cetera. Ironically, only his fellow veteran of American imperialist adventure in East Asia, Brad Wesley, shares this need to control the narrative.

Oh, Donny? Donny’s literally taking a back seat, literally a few steps behind. (Windshield’s out, Dude.) Lacking any physical or intellectual agency, he’s just along for the ride. He has no character in Road House. Unless…unless…

025. Tableau

January 25, 2019Though Dalton gets stabbed within the first few minutes of Road House, it would be incorrect to refer to the incident as a fight. He weathers the cut with stoic grace, lures the wielder of the blade into the parking lot of the Bandstand under the false pretense of giving him the honor of a mano a mano throwdown, and then walks back inside, closing the gates of paradise behind him with a row of mountainous bouncers.

The real first fight occurs about 15 minutes in, when Dalton first arrives at the Double Deuce. Let us leave aside the manner in which the fight begins, for now; suffice it to say it involves the violation of a verbal contract and a subsequent falling-out between the negotiating parties. Let us also avoid discussion of the fight’s particulars, each of which will likely receive an entry of its own. Here our focus is on the fight’s gestalt. As much as the Shirtless Man or the Four Car Salesmen or the Bouncer Fame Index, it is an indication of the kind of movie you’re watching, and the most visceral and ambitious one at that. And it indicates this: You are watching a movie in which barfights achieve the colossal scale and cacophonous visual intensity of a painting from the Flemish Renaissance.

While, again, avoiding the instigating incident and the individual fight choreography beats, the effect of the first fight is intoxicating—a vertiginous ramping-up of wanton physical stupidity and destruction, from a starting point that is incredibly stupid itself, that simulates the effect of consuming an heroic amount of intoxicants in a time short enough to be the length of a song from Wire’s Pink Flag.

The first time I watched Road House I’d heard about it for a couple of years from the friends who wound up introducing me to it, but really had no idea what the fuss was about. By the time the first fight was over I wondered no longer. While I imagine there are those who do not give themselves over to the movie after this scene, I was not one of them, nor do I truly understand what it would take to be one of them. There’s no resisting the howitzer blast of shattered bottles, smashed tables, flying bodies, and punched heads you witness here, nor the rogues gallery of one-off stuntpersons who produce them.

And while Dalton himself stays out of the fray, watching it all unfold with the sangfroid only America’s second most famous bouncer could muster, you the viewer are afforded no such luxury. You pinball around with the camera as every act of stupendously dumb violence is rubbed right in your face. As a collection of individual moments, shots, characters, punches in the head, it’s truly impressive.

But when the camera pulls back and the full scale of the devastation is revealed for the first time? Breathtaking. Staggering. Clarifying. In that one moment you mentally whip-zoom from the trees to the forest, the way you might look back at a particularly harrowing stretch of events in your life and think “my god, how did I ever make it through?” The parts overwhelm moment to moment. The whole overwhelms on a whole other level, yet none of the parts are concealed. Everything is happening.

And you’ve emerged on the other side, with roughly a Tilghman’s eye view of the conflagration. You see the magnitude of the task Dalton has taken on, even as he casually strolls through the still-raging slobberknocker to confer with the bar’s owner. You see the movie you’re about to spend another hour and a half watching, itself a collection of individual moments, shots, characters, and punches in the head—just as chaotic as this one image, and just as cohesive a statement.

024. Mr. Clean

January 24, 2019Dalton’s first visit to the Double Deuce is, it’s reasonable to assume, a representative view of the establishment’s clientele. He is harassed in the parking lot by a gang of bikers angry at him for driving a Mercedes instead of Detroit steel. Inside the bar he passes two women pawing at their noses clearly after powdering them in the ladies’ room. (A minute or two later we see them approach the Double Deuce’s resident drug-dealing waitress to purchase the cocaine they just used, a transaction she tells them she will complete in the ladies’ room. I suppose it’s possible they just needed more and not that they entered the Moebius, a twist in the fabric of space where time becomes a loop.) He sees a hayseed who looks like Jeff Foxworthy sexually harass his future friend and Dionysian acolyte Carrie Ann. He watches Regular Saturday Night Thing Steve refuse to break up a rolling-around-on-the-ground fight because the participants are brothers.

The first person to actually acknowledge the presence of Dalton inside the Double Deuce is a man who is cueball Kojak bald, at a time when that was still unusual enough to be striking. When Dalton parks himself at the corner of the bar nearby, this fellow gives the newcomer a polite wave hello. He then stands up, tucks his chin against his neck in the fashion of someone who has just involuntarily re-tasted an hours-old meal, and raises his eyebrows like he’s surprised he’s still mobile. He is drunk as a lord. He toddles away in the fashion of a person who is mustering literally all of his physical and mental energy just to make it to the bathroom without exploding out of both ends.

I think of this guy as Mr. Clean, for obvious reasons, and for lack of a better descriptor. And why not? Despite being both friendly and nonviolent, he’s nevertheless exactly the sort of 40-year-old adolescent, power drinker, felon, and trustee of modern chemistry Dalton will go on to tell his underlings it is their job to expel from the Double Deuce forever. Dalton is here to clean up the likes of Mr. Clean.

Yes, Mr. Clean offers Dalton a comparatively warm welcome, before lurching out of frame and out of the film forever. What of it? This will hardly be the last time that those Dalton must destroy approach him in the guise of friendship. In the words of Dalton’s First Rule: Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected. Including a polite little wave hello.

023. Valet

January 23, 2019This man is Chino “Fats” Williams. A character actor with a string of bit parts from the ’70s through the ’90s, he appeared as a character called Fats in four different projects, from Baretta to House Party. In Road House he’s billed as “Derelict,” which coincidentally or not is the same title he receives in Rocky III, the third and final installment of that franchise in which he acted as a downwardly mobile person. It is unclear whether he was playing the same person in all three Rocky movies, and equally unclear if the Derelict from Rocky III is the same Derelict from Road House, and thus if Wade Garrett and Ivan Drago exist in the same cinematic universe. An enterprising mid-tier comics publisher should look into the rights situation, because that is the crossover event of the century right there.

Be that as it may. Dalton knows none of this when he drives up to the New York parking garage where he stores his Mercedes, which he plans to take to Jasper. By now you’ve read enough to know that he always stashes his fancy ride away when he’s working so that angry customers don’t take out their frustrations on it, replacing it with some old beater or other, the way you wear a ratty old t-shirt to do serious housecleaning or what have you. This means that after quitting the Bandstand and agreeing to work the Double Deuce, he has to get rid of his New York jalopy before he can head for Missouri.

He does this by parking in front of the garage and tossing his keys to the above individual, who’s seated comfortably outside the garage entrance. Both confused and irritated, the man says to Dalton, “What do I look like, a valet?”

The answer, frankly, is yes.

He is sitting expectantly in front of a parking-garage entrance in the middle of the night on an otherwise empty street. God knows what else he’d be doing there.

But this is beside the point. The important thing about Chino “Fats” Williams and his Derelict role is the voice with which he says his one line. The best way I can describe it—and I’ve thought about this for years—is that he sounds like if Statler & Waldorf from The Muppet Show gargled with razor blades and then sucked down a bunch of helium. “Elderly frog angry about getting thrown out of a bar for chainsmoking” could work as well. The man has the most memorable voice in the movie, which I remind you also stars Sam Elliott, Terry Funk, Kevin Tighe, Ben Gazzara, and Keith David (kinda). He may or may not look like a valet, but he sounds like no one else on earth.

Anyway, turns out Dalton neither knows nor cares who he is. He tossed the guy his keys because he’s giving him the car. “Keep it, it’s yours,” says the nation’s second-greatest cooler. “Mm?” murmurs the Derelict quizzically. “Mm,” he responds to himself firmly. With a little “Well, alright, if you insist” shrug, he gets up and heads to the car. Apparently he has places to be, though you wouldn’t have known it from the fact that he’s sitting by a parking-garage entrance alone in the middle of the night like…well, you know.

022. An elevator in an outhouse

January 22, 2019“Callin’ me ‘sir’ is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse: It don’t belong.” So says Emmet, Dalton’s prospective landlord, to Dalton, Emmet’s prospective tenant, soon after they meet. Dalton is unflaggingly respectful to those his cooler-sense tell him deserve respect. Emmet, with his overalls and scraggly beard and extremely menacing hay-hooks, is such a fellow, hence Dalton’s use of that three-letter term of deference. Emmet in turn is determined not to put on airs, even at the expense of seeming less of an authority figure in the eyes of someone in whom he must trust to behave himself on their shared property on whom he will soon depend for income. In a minute or two he will rent Dalton a massive, fully furnished loft apartment for $100 a month, which is one-fifth of what Dalton makes every day, so he’s clearly willing to forego other markers of landlordism too. But in the meantime, an analogy that has never before passed the lips of man will have to do. I’d say it’s a singularly odd and vulgar expression to coin, but we’ve got “balls big enough to come in a dumptruck” and “does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick” and “I used to fuck guys like you in prison” to contend with in this film alone, so “singularly” is out. Still, this is our first taste of Road House‘s penchant for turning a phrase until it gets dizzy and collapses, and thus it’s a memorable one.

But it wasn’t until yesterday, writing about the sign that welcomes weary travelers to Jasper, that I got to thinking about how well the expression sums up the existence of Emmet and Dalton’s soon to be shared enemy, Brad Wesley. Like an elevator in an outhouse, Wesley represents the intrusion of commodification (as opposed to commode-ification) and technological overreach in the Jasper ecosystem. His house is the biggest house. His businesses are the biggest business. His goons are the biggest goons. His truck has the biggest wheels. Were he to construct an outhouse, an elevator is not out of the question.

What’s more, so many of his scenes are literal intrusions into places he does not belong: the opposite lane of traffic, the post-cleanup Double Deuce, the auto parts dealership run by the uncle of his ex-wife, Pete Strodenmire’s Ford showroom, and—most importantly, since the “elevator in an outhouse” exchange is bookended by it—the airspace above Emmet’s ranch. As Emmet and Dalton meet and negotiate, Brad buzzes them with a helicopter that, like his in-ground pool and his monster truck and (one presumes) his JC Penney, feels about as out of place in this environment as…well, you know.

Brad Wesley livin’ in Jasper is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse: He don’t belong. If you’ll permit me to take the analogy one step further: No matter how far up he may go, he’s still just a pile of shit.

021. Welcome to Jasper

January 21, 2019

It would be incorrect to say that the “Welcome to Jasper” sign situated atop a clock in the town’s main thoroughfare is the sight that greets Dalton when he first drives into town, because he’s driving into view from the opposite direction. This leaves us with two possible interpretations. Either he’s driven clear across town from one end to the next just to take the place in and we’re catching up with him as he hits the opposite border from where he started, or this sign is an ad hoc affair in a shot the logic of which was not exactly thought through by the film’s director. Considering the strange effect cars seem to have on the amount of sense the movie makes at any given time I lean towards the latter interpretation.

Be that as it may, I hope Dalton caught it in his rearview mirror as he passed by, because it tells him a lot about the town, and the main body of the movie, he’s about to enter. The bright green neon signage is an unusual choice, either for a border marker or for a greeting from the town’s main shopping district. It evokes the neon of the Bandstand sign more than the wooden billboard paid for by the local Rotarians. That, at least, I believe was intentional on the part of the filmmakers. You are entering a Road House town.

The neon itself rests atop a tony-looking Seth Thomas clock. The same manufacturer created the clocks that greet travelers in Grand Central Station. It’s emblematic of both a bygone time and the promise the future held during that time, a past-future when it was possible to go anywhere and be anyone. The neon, too, has its own retro connotations, more sock-hop than Beaux-Arts. They don’t match up.

The combination makes sense only in the context of the film-Jasper’s crazy-quilt approach to authenticity. This is a town of bearded old codgers who raise horses, and also have expensive faux-rustic loft apartments in their barns, located directly across the water from mansions with property big enough for helicopters to land on. It’s the home of countrified fellas named Red who run small auto-parts stores and huge Ford card dealerships, both of which are held up to be models of small-business entrepreneurship against Brad Wesley’s chain-store depredations. It’s a place where one dive bar out of several that we visit can be the stomping ground of a clientele straight out of The Road Warrior one month and a mecca for nightclubbers who pay top dollar to see a blind white boy play the blues the next, predicated on the garish design sensibilities of the bar’s rich owner and the ability of the bar’s cooler to settle all problems in the town with violent force.

And you know that “main thoroughfare” bit? Who knows! I basically made that up, since we never see this place nor anywhere remotely like it ever again. This crowded stretch of commercial development with decent walkability and the network of dirt roads, junkyards, and greasy-spoon diners the rest of the movie traverses have about as much in common as, well, the clock and the neon sign. But each stretch of road broadcasts realness.

Dalton intuits this, which you can see in the way he self-effaces regarding his fancy degree from New York University, but takes the ancient practice of tai chi directly to the shores of Jasper’s lake-river. By turning the sign away from Dalton’s point of view at this early moment, Dalton’s status in the town is left an open question—one quickly answered, true, but that answer is earned. Dalton is welcome in Jasper.

Brad Wesley talks a good game about small-town values and that old time rock and roll, but everything else about him—riding in a chopper, erecting malls, interacting with nature primarily by killing, stuffing, and mounting wild animals from around the world rather than the good ol’ USA—does not. This makes him an interloper, an occupier, a colonizer, someone as out of place in Jasper as a Calvin Klein’s Obsession ad would be below that neon sign and Seth Thomas clockface. Brad Wesley is not welcome in Jasper.

But you are welcome in Jasper, dear viewer. You are welcome here from the start, trusted by the town to take it into your heart in all its complementary contradictions. You must be, because it’s the only way to move forward and drive on to what awaits.

020. Nothing personal

January 20, 2019“I want you to remember that it’s a job. It’s nothing personal.” We’ll be exploring of Dalton’s three simple rules for bouncing my Jasper road house in depth as the year progresses, but this elaboration of Rule Three, “Be nice,” bears scrutiny here in this early stage of the game. If you want to know what Dalton’s about, you need to see how seriously he takes not taking things personally. For now.

On Dalton’s first night on the job—the night of the Giving of the Rules—he makes a lot of enemies. He fires Morgan the bouncer for being a rat-bastard sadist and Pat McGurn the bartender for stealing from the register; both these men are members of the Wesley outfit and will repeatedly attempt to murder Dalton for costing them their jobs at what is, let’s face it, a complete shithole. He fires Steve the bouncer for having sex with teenagers on the job and he fires Judy the waitress (not that anyone ever says her name in the movie, of course) for dealing drugs on the job; neither shows up again but it’s hard to imagine losing their sexually and/or financially lucrative side hustles along with their day jobs sits particularly well with them. He also encounters a man who reacts to being asked to escort his girlfriend off the table she’s dancing on by whipping out a switchblade and threatening to stab a bouncer to death, and uses this man’s face to break a separate table in half before throwing him out; provided he hasn’t suffered a brain injury, my guess is he’s pissed off about it.

So there’s no surprise, and no shortage of suspects either, when Dalton walks outside and sees that his new car has had its windshield shattered, its antenna broken, and all four of its tires slashed.

Dalton saw this coming, of course. As previously mentioned, he makes it a habit to buy a beat-up used car while he’s working, knowing how the people he alienates tend to react. But this isn’t grudging acceptance of a bad situation, the way you might grumble standing on line at the grocery store the night before a big snowstorm. When Dalton sees what’s been done to his car, which will require him to jack and replace all four tires at a minimum before he can even think of addressing the other problems, he simply smiles and shakes his head. He’d shoot the same you-gotta-laugh look if he had a toddler who just covered her hair with peanut butter.

This is the face of a man who has a job, who does the job, and who does not take the job personally. His background in philosophy might help. Same with his study of tai chi. And in general he reverts to “laid back” as a default setting when external stressors are absent. And I mean that literally: When Wesley sends his goons Tinker and O’Connor, who recently tried to murder him and got their clocks cleaned for their troubles, to fetch him for a sit-down, he’s lying on the car that their fellow goons most likely vandalized the way a normal person might relax on a hammock.

But the “it’s a job, it’s nothing personal” thing is crucial to understanding the transformation Jasper, Missouri forces him to undergo. With each scene, you can watch his progress from one end of that spectrum to the other. Just know that this is where he starts.

015. The Shirtless Man

January 15, 2019A key piece of the ambience during our introduction to the Double Deuce, the Shirtless Man is an unsung hero of Road House. He’s on screen in the shot that immediately follows the “DIRECTED BY ROWDY HERRINGTON” chyron, shown over the exterior of the Double Deuce as Dalton enters for the first time. This means he’s a tone-setter both in-story and on a meta level. In the Road House world, he is implicitly Dalton’s introduction to the place he’ll be working in, and an indication of the kind of place this is. In the audience, he is implicitly crucial to director Rowdy Herrington’s vision, and an indication of the kind of movie this is.

This pans out in both respects. It’s true that the Shirtless Man does not participate directly in any violence; in the massive, bar-destroying brawl that begins a few minutes after we first see him he’s a non-factor. He’s just a huge blond musclebound cornfed doofus, dancing his ass off to the musical stylings of the Jeff Healey Band. Picture the way Rocky rocks out to Meat Loaf singing “Hot Patootie – Bless My Soul” in The Rocky Horror Picture Show and you’ve got a good handle on his overall affect (and talent as a dancer).

But I think of the Shirtless Man often later in the film, when Dalton institutes his clean-up regime to turn the Double Deuce into a place decent people will want to visit. We’ve discussed some of the personnel changes he makes already. The other problem, as he sees it? The thing that’s keeping “people who really wanna have a good time” away? “Too many 40-year-old adolescents, felons, power drinkers, and trustees of modern chemistry.” It’s unclear into which category the Shirtless Man falls, but it’s almost certainly at least one, if not more.

Sadly, the new and improved Double Deuce has no room for men this brazenly bare-chested. There’s a time and a place for shirtlessness, and it’s on the shore of the lake, doing tai chi. The next time we see the Shirtless Man is on Dalton’s first real night of work there; what he’s wearing wouldn’t pass a high school dress code, but it certainly qualifies as a shirt. After that things really turn around and we never see him again.

Yet his ebullient presence at this stage in the film points out a rare flaw in Dalton’s reasoning. Later in the movie, when Brad Wesley’s knife specialist Ketchum (please note that he is never named in the film, unlike all the other prominent goons who make it to the end, which is a part of why he’s impossible to remember) arrives to rough the place up, Dalton says the place is closed, despite all the people “drinking and having a good time.” Ketchum says that’s why he and his henchmen are there too, and promptly tries to kick-stab Dalton’s head with a high kick from his boot-mounted knife. Dalton doges the kick, catches his leg in mid-air, and bellows “You’re too stupid to have a good time!”

The emotional logic of the fight that follows puts Dalton in the right; he and the bouncers defeat Ketchum and his fellow goons, with a late-arriving Doc looking on. But he didn’t factor the Shirtless Man into his calculations, did he? That big towheaded slide of beef is most likely stupid, and is very clearly having a good time when we see him. You can push him and his kind out to make room for people who don’t violate the basic tenets of entrance into a 7-Eleven, yes, but you can’t erase his existence. Dalton may deny it, but if Road House teaches us anything, it’s that stupidity and good times often go hand in hand, and the Shirtless Man is living proof. There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy degree from NYU.