Posts Tagged ‘brad wesley’

106. Sightings

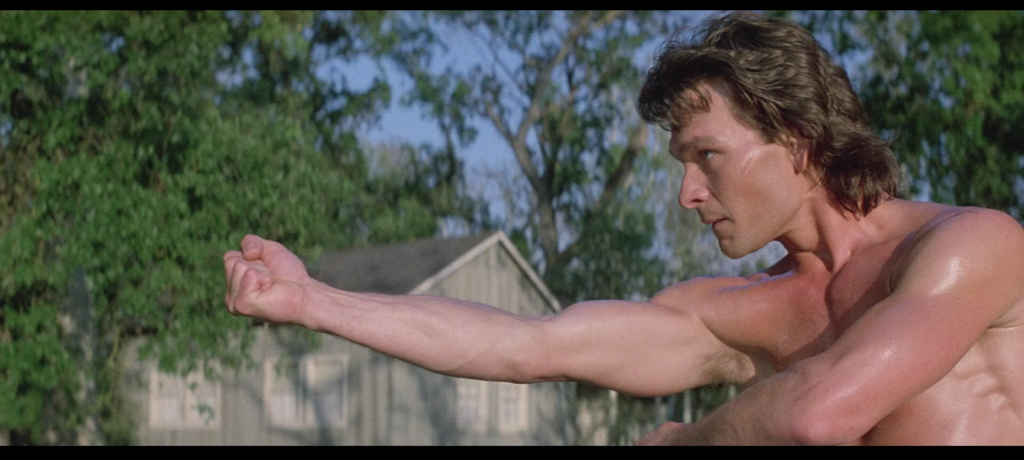

April 16, 2019Flipping through my copy of Road House today, waiting for inspiration to strike, I came across one of my favorite goofy moments in the movie: Brad Wesley stopping his ATV, which he’d been driving around he lawn of his mansion or something I guess, in order to watch and gently scoff at Dalton doing tai chi across the river. The combination of factors at work here—a shirtless and glistening Patrick Swayze performing tai chi on the Missouri farm where he lives during his stint as making six figures at a local shithole as part of his career as a famous bouncer, a deranged JC Penney enthusiast finding this interesting enough to park his Big Wheels and watch but ultimately come away unimpressed, as if he’d expected better form, or a dryer torso—is irreplicable in any other film.

But something hit me about Dalton, as seen from Wesley’s point of view in this moment. Something that I have seen in another film, albeit not a feature. Something that comes close to capturing our sense, and perhaps Wesley’s sense too, that when we look at Dalton we’re seeing something that defies comfortable categorization. Something wild, mysterious, dangerous, untamed, and all but extinct.

100. Pain don’t hurt

April 10, 2019Look, all he’s saying is that it doesn’t bother him that much. Why would you doubt him? You’ve just read his life story in the form of a medical file. Thirty-one broken bones, two bullet wounds, nine puncture wounds, and four stainless steel screws. To these you are about to add nine staples, to close the knife wound he incurred in the process of physically fighting multiple armed attackers in his employer’s office. He’s a bouncer by trade, and taking it is as much a part of the job as dishing it out. More so, perhaps. The fight has to come to him, not the other way around. Until someone’s ready and willing and able to hurt him he’s off duty. So he turned down the anesthetic, so what. Pain is how he clocks in.

But there’s more to it than that, you suspect. Because the non-standard subject-verb agreement is…it’s cute, you guess, but you know he knows better. In that job, with that body—you’ll afford him the working-class hero affectation, but that’s what it is. Again, you’ve read his medical file. You know he went to NYU. You know he keeps this information in his medical file, for some reason. You suspect, in the minute you’ve known him you suspect, that he’s put real thought into the things he says, for better or…

Beautiful eyes. Blue. He has a blue-eyed smile, too, you think, unsure what that means, sure that it’s right.

You’ve been with violent men before. There, now you’ve thought it, now it’s out in the open. Not with you, never with you, not really, no not really, though you’ve heard things since then that you have a hard time believing yet also believe the moment you hear them. What’s that girl’s name? The blonde woman. She was with one of his boys, and you were with him, and you left town, and he went nuts, and now she’s with him and the boys have moved on, you suppose. Not with you, though, not really.

But Brad didn’t need to hit you to hurt you. His charisma, his worldliness, his ease with success, the way he promised you everything and meant it: When you saw it for what it was—for its casual cruelty and gross acquisitiveness and lack of empathy and small-minded understanding of what “everything” even means—and the life you’d planned to last forever kindled and burned and crumbled to ash in the light of it, oh, he hurt you then. He hurt you so badly you ran to get away from it, like the feelings lived in that godawful mansion and you could leave them there mounted on the wall, immobile, unable to reach you again.

Has he ever been hurt, you wonder? Hurt like that, you mean? Has Dalton comma James, he of the thirty-one broken bones, two bullet wounds, nine puncture wounds, and four stainless steel screws—and nine staples, don’t forget those—has this man who literally trailed blood into your hospital tonight ever tried to run away from the pain, only to learn just like you did that you take it with you no matter where you go?

You want to check his medical file for the answer. You wonder if maybe it’s on the same page that lists his alma mater. You want to laugh but that would be inappropriate.

But you have your answer. You may not want to believe it, because it’s safer not to. But the working-class hero with the NYU degree and the studiously sculpted body and the equally studiously sculpted speech, with the blue eyes and the smile, with the thirty-one broken bones and two bullet wounds and nine puncture wounds and four stainless steel screws and, soon, nine staples—he told you already.

He told you, when he said Pain don’t hurt.

No, you think. By comparison? No. No, it does not.

You’re still smiling, you realize, you’re still smiling and he’s still smiling as you turn to grab the stapler. As you feel his body through the latex of your glove and begin to repair what was broken you think Pain don’t hurt and you wonder how long the smiling will last.

099. The Phantom Menace

April 9, 2019WESLEY: This is my town. Don’t you forget it.

DALTON: So what does he take?

RED: Who?

DALTON: Brad WesIey.

RED: Ten percent…to start. Oh, it’s all legal-like. He formed the Jasper Improvement Society. All the businesses in town belong to it.

DALTON: You’ve gotten rich off the people in this town.

WESLEY: You bet your ass I have. And I’m gonna get richer. I believe we all have a purpose on this earth. A destiny. I have a faith in that destiny. It tells me to gather unto me what is mine.

RED: Twenty years I’ve watched Wesley get richer while everybody else around him got poorer.

TILGHMAN: Anyway, I’ve come into a little bit of money.

TILGHMAN: This is our town. And don’t you forget it.

073. Lebowski II: Garden Parties (continued)

March 14, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a shady business mogul played by Ben Gazzara flouts decency standards in a waterfront community that he controls through a combination of extravagant wealth and muscular morons. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film in which Gazzara reprises this role.

The two orgiastic parties thrown by the Gazzara characters in these movies, Malibu pornographer Jackie Treehorn in the latter and Jasper JC Penney enthusiast Brad Wesley in the latter, have so many surface-level similarities it remains difficult for me to believe that Joel and Ethan Coen were not familiar with Rowdy Herrington’s masterpiece when they made their own. Smiling men tossing topless women through the air, the bright blue of a pool juxtaposed against the dark of the night, a general “the night time is the right time” atmosphere, the dramatic entrance of the Gazzara characters themselves, goons—it’s all there.

Yet the differences reveal much, as they typically do, even as they point to how similarly the two films often function. I vividly remember going to see Lebowski at the movie theater when it debuted and finding it a sensational film, in the sense that on a scene-by-scene basis I felt buffeted by new and unprecedented forms of ridiculousness. The Treehorn beach party is way way up there on the list, beginning as it does with a topless woman plummeting through a void with the otherworldly voice of Yma Sumac blasting at full volume. This is the impression Treehorn wished to make on the Dude as well, whom he used his goons to summon to his estate, impressed with the excess and splendor of his lifestyle, lulled into a false sense of security, drugged, and dumped in the street. It was a party for himself and his, I dunno, friends I guess?, but it was also a performance for one Jeffrey Lebowski. Treehorn’s direct-address introduction of himself right into the camera speaks to that.

Brad Wesley’s idiotically raunchy shindig has no such purpose. He and his men and women have no idea Dalton is watching from across the river; indeed it’s unclear if at this point in the film Wesley has any idea where he lives at all, and furthermore Dalton makes an effort to hide his observation of the party by switching off the light by which he was reading a Jim Harrison novel when the noise of the soiree first distracted him. Additionally there is nothing particularly disorienting or otherworldly about this parade of gawping meatheads and Mötley Crüe video extras—they simply run out of Wesley’s house in a surprisingly orderly line, start stripping off their clothes (“hot babe” bikinis for the women, the usual thug-casual style for the goons), and boogie down to Bob Seger’s “Monday Morning” of all things. Wesley arrives last but he incorporates himself into the festivities rather than set himself apart, joining his girlfriend Denise and pinching the cheek of Mountain, his tallest and goofiest goon. Where the Dude is duly impressed by Treehorn’s milieu (“Completely unspoiled!”), Dalton is merely amused by Wesley’s, a fair and perhaps even generous reaction to a party at which a central component is Terry Funk with his pants around his ankles.

The point I’m trying to make is that while the Ben Gazzara party scene in The Big Lebowski serves a concrete purpose for the Ben Gazzara character, the Ben Gazzara party scene in Road House exists simply to entertain an audience the film presumes to be pretty stupid, or at least open to enjoying pretty stupid things. Dalton, a man of diverse interests, enjoys it just fine. Thus Wesley’s power to impress and intimidate Dalton with his Dionysian powers is dissipated. When he finally does attempt to bowl the cooler over with demonstrative partying and sexuality deep into the film, when he has Denise strip at the Double Deuce as a show of masculine force, Dalton is completely impervious. This party is a vaccine.

072. Lebowski II: Garden Parties

March 13, 2019070. Face to face

March 11, 2019

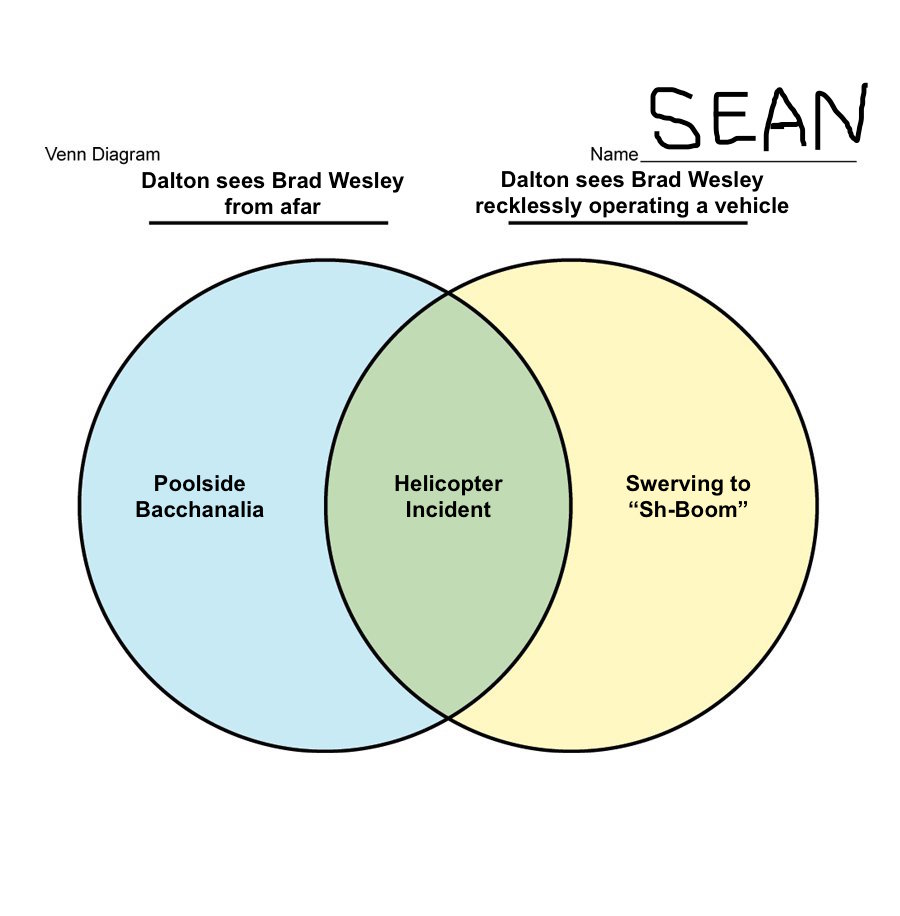

This is not the first glimpse of Brad Wesley that Dalton has gotten. Since arriving in Jasper, Dalton has seen Brad Wesley twice from afar, first when Wesley’s helicopter buzzes Emmett’s horses, later when he watches Wesley’s poolside bacchanalia from across the river. Dalton has also seen Brad Wesley twice while recklessly operating vehicles, first the helicopter incident and then when Wesley nearly runs him off the side of the road as he swerves back and forth singing “Sh-Boom.” Here’s a Venn diagram to help you keep track.

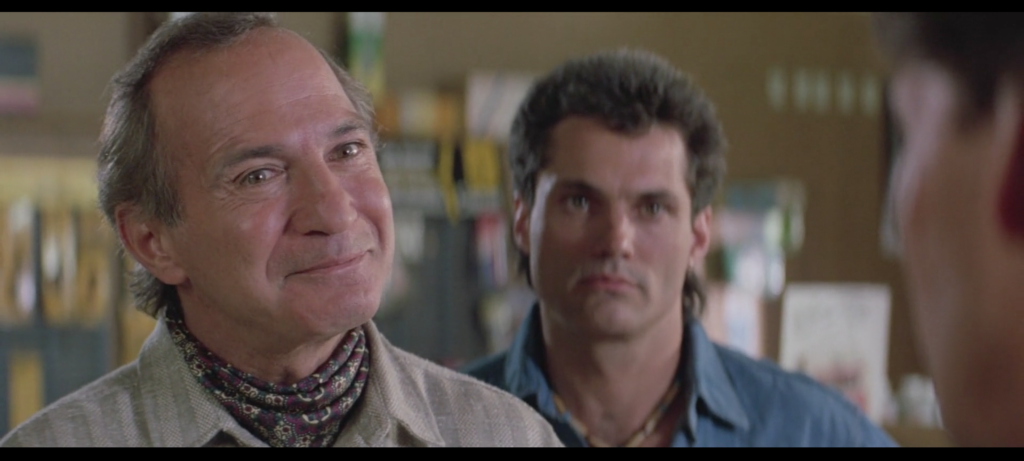

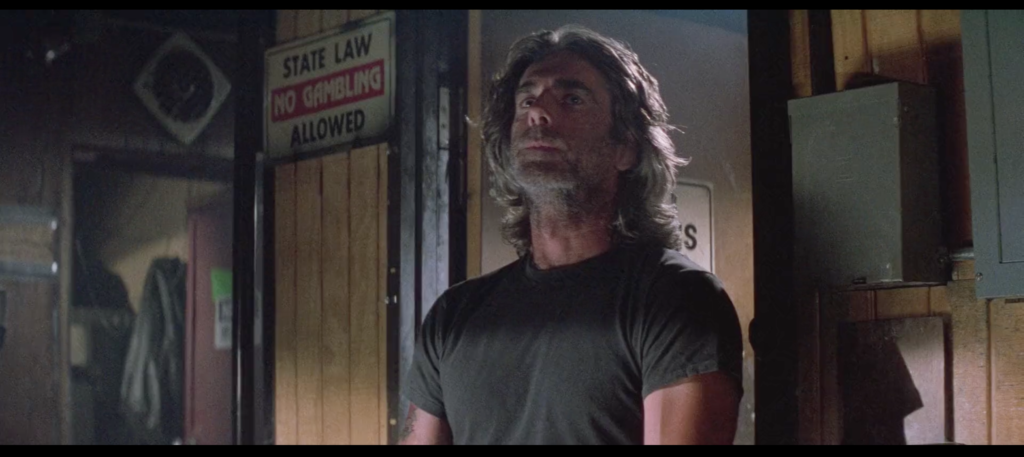

But their encounter inside Red Webster’s auto parts store the day Dalton visits to buy what he needs to repair his vandalized car is the first time Dalton and Brad Wesley meet face to face. No sparks fly. No cutting words are exchanged. They don’t even shoot each other dirty looks, though Red sure is unhappy to see Wesley and Wesley’s bastard son (source for this claim?) Jimmy stares at Dalton like he’s a starving man and Dalton is a steak he’s really mad at for some reason.

No, it’s all smiles and handshakes when these future nemeses first meet. Wesley exchanges his hand and introduces himself, Dalton takes it and returns the favor. Red even goes so far as to explain to Wesley that “He’s working at the Double Deuce,” though whether to subtly impress upon the nefarious businessman that the bar will no longer be easy pickings for him or to simply make smalltalk with a man with whom he’s forced to be cordial is anyone’s guess. “Oh, terrific, hope you’re gonna clean that place up!” Wesley enthusiastically croaks. “Bad element over there. Well, anything that I can do for you….” Later that day Wesley will send Tinker, O’Connor, and Pat McGurn to the Double Deuce, and two of those men will attempt to murder Dalton at knifepoint. For now Dalton simply returns Wesley’s friendly grin, thanks Red for the aerial, and meets Jimmy’s steely gaze as he exits the place.

If you’ve read seventy essays about Road House in seventy days you know enough about Dalton to know he hasn’t been snowed by this dude. For one thing there are his previous three first impressions of the man, none of them good. For another it’d be hard to miss the way Red tenses up when Wesley walks in, or the fact that Wesley travels to the auto parts store with a dead-eyed denim-clad psycho who looks like he came home from ‘Nam with one of them funny necklaces. Indeed it seems fair to assume that the reason Dalton performs tai chi by the riverside while glistening with sweat later that afternoon is to shake the spiritual residue left behind by Wesley (who watches him from afar this time, chuckling to himself with amusement). No, Dalton’s cooler-sense is tingling, you can bet on it.

But Red Webster’s auto supply store is a place of dreams, a nexus, if you will, of realities that are and were and yet may be. Is it so hard to imagine a world in which this handshake, these smiles, are the sum total of the interactions between these two men? A world at peace, in which the war between Dalton and Brad Wesley never takes place, where countless limbs go unbroken, where multiple homes and businesses are never destroyed by explosives or monster trucks, where no one dies so that the new Double Deuce might live?

059. Men in Black

February 28, 2019When I wrote about Wade Garrett yesterday, I remembered something about his black t-shirt: He’s not the only cooler in the movie to wear one. The other of course is Dalton—but it’s not like he wears it all the time. The movie shows us he’s molded in Wade’s by deploying black in his wardrobe on three key occasions.

Attentive readers of Pain Don’t Hurt will have guessed the first by now: The Giving of the Rules. This takes place prior to Wade’s introduction, directly linking the older man’s debut to the establishment of his acolyte’s doctrine.

The second is the fight that takes place the night he and Doc have their first date, which is also the first time we see him on the job after we meet Wade. This reinforces the sense of succession while also tying Dalton’s romantic flourishing to the older man’s tutelage.

The third is his impromptu breakfast summit with Brad Wesley, during which Wesley brings up his checkered past and offers to hire him away from the Double Deuce. It’s not a t-shirt here but a collared shirt, as befits this more formal occasion. But the dialogue makes direct reference to an event in Dalton’s past that Wade will also bring up (while wearing a collared black shirt himself) later in the movie, and shows Dalton standing up to an asshole in a way that would do his mentor proud—even if he’d likely suggest getting out of Dodge afterwards.

Clothes make the man. Clothes mate the men.

057. “It’s my way or the highway.”

February 26, 2019Dalton, during the prologue of The Giving of the Rules: “It’s my way or the highway.”

The highway:

Show me the lie.

Whether by accident or design—who can say? alright I can say, it’s by accident—there is no aphorism, no catchphrase, no idiomatic expression, no imbecilic threat or come-on or dick joke in the entirety of this film that does not bear close, even literal, reading. This is what I want to impress upon you more than anything else. This is what inspired this project: the sense that in the 15 years I’ve been watching this movie I haven’t touched bottom any more than you might during a swim in the middle of the ocean. Road House is a journey of discovery, a highway if you will, and the higher you fly the deeper you go the deeper you go the higher you fly so come on come on come on it’s such a joy.

032. Sh-Boom

February 1, 2019Originally recorded by doo-wop group the Chords, who charted with it in 1954, “Sh-Boom” became part of the pop-culture firmament largely because of a cover version by the Crew Cuts that was also a hit later that year. Both versions are the kind of gleeful pure-dee nonsense that make doo-wop such a fun genre to pronounce, let alone listen to. While Chords’ rendition has a jaunty swing to it, the Crew Cuts’ whitebread revamp emphasizes the gliding, carefree, “life could be a dream” side of the song. It sounds like a Sunday drive.

Of course, most people content themselves with driving on the right side of the road, Sunday or any other day, whether they’re listening to “Sh-Boom” or “Yakety Yak” or “Symphony of Destruction” by Megadeth. This is not just because it’s the law, or because it’s much safer not to drive into oncoming traffic. It’s because staying in your lane allows you to chart a long straight course, and a long straight road is the most fun kind to drive. The Germans modeled a whole genre of music after it and everything.

When we see Brad Wesley driving his red convertible (a Ford, possibly ill-gotten from Strodenmire’s ill-fated Ford dealership) with the top down on a bright sunny day, the fact that he’s singing “Sh-Boom” fits. It’s that kind of song. Wesley is also swerving from one side of the road to the other and back, over and over, like a sine wave, like a snake. This, too, fits. He’s that kind of person. But the actual driving process deserves closer examination.

Until Dalton passes by headed in the other direction, nearly getting run off the road in the process, there isn’t another car in sight. Wesley has the road all to himself. He could comfortably cruise along, taking in the air and the scenery. He could floor it if he felt the need for speed. (“He’s go the sheriff and the whole police force in his pocket,” Red Webster tells Dalton later in the film; the line is likely intended to explain why crimefighting in Jasper is entirely the province of bouncers, but it explains a lot of other things too.) This is what normal people who enjoy a nice drive would do.

As anyone who’s whipped around an empty high-school parking lot could tell you, rocking the steering wheel back and forth like Wesley does creates a push-pull swerving sensation that’s much more enjoyable in theory than in practice. If you’re a 17 year old looking for a quick thrill when you’re all out of kratom or whatever, sure knock yourself out. But to drive that way over a significant distance is less fun than just driving straight, not more.

Ben Gazzara sells the nauseating joyride as well as you’d expect from an actor who, prior to Road House, created the role of Brick in Cat in a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams. And indeed we can take Wesley’s glee as entirely sincere, but not because he’s having fun driving in and of itself. He has gone out of his way to make his drive less physically enjoyable, because the thrill of being a gigantic asshole and recklessly endangering the lives of others more than compensates for the loss.

This is the kind of man Brad Wesley is. He can hey-nonny-ding-dong-alang-alang-alang his way back and forth across every inch of asphalt in Jasper and none can say him nay. That’s worth a crick in the neck.

030. “My only sister’s son”

January 30, 2019“I name Éomer my sister-son to be my heir.”—Théoden, The Lord of the Rings

“He’s my only sister’s son, and if he doesn’t have me, who’s he got?”—Brad Wesley, Road House

Not even I, a person with the White Tree of Gondor tattooed on my arm who is writing an essay about Road House every day for a year, can come up with much of a connection between the King of Rohan and the Chief Job Creator of Jasper, Missouri beyond the antiquated syntax with which they refer to their nephews, Éomer son of Éomund and Pat McGurn respectively. Wesley isn’t about to name his mustachioed kinsman his successor anytime soon, certainly. “Pat’s got a weak constitution, you boys know that,” he tells his assembled henchmen after two of their number, Tinker and O’Connor, failed to forcibly reinstate Pat in his old gig at the Double Deuce during one of the Knife Nerd incidents. “That’s why he’s working as a bartender.” Poor Pat, not even fit for full-time goonmanship.

Pat isn’t even present to hear this condescension, having slunk shamefacedly into Uncle Brad’s mansion at the first opportunity, allowing his comrades-in-goon to take the heat. Why should he bother sticking around? He knows his place, and it’s not at his uncle’s side. It’s Jimmy, Wesley’s strong right hand and, in my considered opinion, secret bastard son who’s the heir apparent. “I should have let you go, Jimmy,” Wesley says regarding the failed mission, an avuncular (fatherly?) hand on the back of the younger man’s neck. Better for Pat to spare himself the sight.

So no, Wesley’s rhetorical style here doesn’t remind me of Théoden King. Rather, I’m put in mind of another great man.

Jack Lipnick is the head of Capitol Pictures, the studio that hires a certain New York playwright to give a Wallace Beery wrestling picture That Barton Fink Feeling. Like Brad Wesley, he came up the hard way (“I mean, I’m from New York myself. Well, Minsk, if you wanna go all the way back—which we won’t, if you don’t mind, and I ain’t asking”) and rose to prominence and power by exerting control over the local economy, largely by screwing other business owners out of their share (regarding his assistant Lou Breeze: “Used to have shares in the company. Ownership interest. Got bought out in the Twenties. Muscled out, according to some. Hell, according to me”).

The tone Lipnick adopts when speaking about producer Ben Geisler, whom he fires instead of Barton when the latter screws up, sounds familiar. “That man had a heart as big as the all outdoors, and you fucked him!” he says, voice soaring as if with the eagles as he describes the generosity of spirit found in a guy he shitcanned, then cracking like a whip as he drops the f-bomb on the person truly at fault, at least in his eyes.

Though he prefers physical assault to firings, Brad Wesley reacts in similar fashion over his sister-son’s plight, arbitrarily beating his goon O’Connor unconscious for, alternately, being untruthful, unable to admit he was wrong, weak, unable to tolerate pain, cowardly and above all prone to bleeding. O’Connor’s failure regarding Pat may have occasioned the beating, but it isn’t even mentioned during the beating itself as one of Wesley’s half-dozen reasons for inflicting it.

For men like Wesley and Lipnick, people are worth caring about only to the extent that doing so, or pretending to do so, enables them to torment others on their nominal behalf. These men, like their words, are overinflated and empty. The overwrought sentiment intended to conceal the lie reveals it instead.

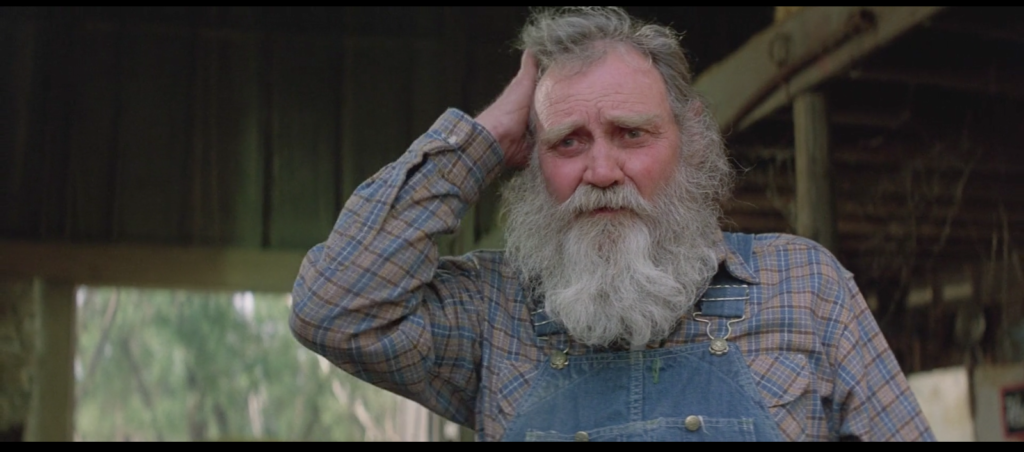

022. An elevator in an outhouse

January 22, 2019“Callin’ me ‘sir’ is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse: It don’t belong.” So says Emmet, Dalton’s prospective landlord, to Dalton, Emmet’s prospective tenant, soon after they meet. Dalton is unflaggingly respectful to those his cooler-sense tell him deserve respect. Emmet, with his overalls and scraggly beard and extremely menacing hay-hooks, is such a fellow, hence Dalton’s use of that three-letter term of deference. Emmet in turn is determined not to put on airs, even at the expense of seeming less of an authority figure in the eyes of someone in whom he must trust to behave himself on their shared property on whom he will soon depend for income. In a minute or two he will rent Dalton a massive, fully furnished loft apartment for $100 a month, which is one-fifth of what Dalton makes every day, so he’s clearly willing to forego other markers of landlordism too. But in the meantime, an analogy that has never before passed the lips of man will have to do. I’d say it’s a singularly odd and vulgar expression to coin, but we’ve got “balls big enough to come in a dumptruck” and “does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick” and “I used to fuck guys like you in prison” to contend with in this film alone, so “singularly” is out. Still, this is our first taste of Road House‘s penchant for turning a phrase until it gets dizzy and collapses, and thus it’s a memorable one.

But it wasn’t until yesterday, writing about the sign that welcomes weary travelers to Jasper, that I got to thinking about how well the expression sums up the existence of Emmet and Dalton’s soon to be shared enemy, Brad Wesley. Like an elevator in an outhouse, Wesley represents the intrusion of commodification (as opposed to commode-ification) and technological overreach in the Jasper ecosystem. His house is the biggest house. His businesses are the biggest business. His goons are the biggest goons. His truck has the biggest wheels. Were he to construct an outhouse, an elevator is not out of the question.

What’s more, so many of his scenes are literal intrusions into places he does not belong: the opposite lane of traffic, the post-cleanup Double Deuce, the auto parts dealership run by the uncle of his ex-wife, Pete Strodenmire’s Ford showroom, and—most importantly, since the “elevator in an outhouse” exchange is bookended by it—the airspace above Emmet’s ranch. As Emmet and Dalton meet and negotiate, Brad buzzes them with a helicopter that, like his in-ground pool and his monster truck and (one presumes) his JC Penney, feels about as out of place in this environment as…well, you know.

Brad Wesley livin’ in Jasper is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse: He don’t belong. If you’ll permit me to take the analogy one step further: No matter how far up he may go, he’s still just a pile of shit.

021. Welcome to Jasper

January 21, 2019

It would be incorrect to say that the “Welcome to Jasper” sign situated atop a clock in the town’s main thoroughfare is the sight that greets Dalton when he first drives into town, because he’s driving into view from the opposite direction. This leaves us with two possible interpretations. Either he’s driven clear across town from one end to the next just to take the place in and we’re catching up with him as he hits the opposite border from where he started, or this sign is an ad hoc affair in a shot the logic of which was not exactly thought through by the film’s director. Considering the strange effect cars seem to have on the amount of sense the movie makes at any given time I lean towards the latter interpretation.

Be that as it may, I hope Dalton caught it in his rearview mirror as he passed by, because it tells him a lot about the town, and the main body of the movie, he’s about to enter. The bright green neon signage is an unusual choice, either for a border marker or for a greeting from the town’s main shopping district. It evokes the neon of the Bandstand sign more than the wooden billboard paid for by the local Rotarians. That, at least, I believe was intentional on the part of the filmmakers. You are entering a Road House town.

The neon itself rests atop a tony-looking Seth Thomas clock. The same manufacturer created the clocks that greet travelers in Grand Central Station. It’s emblematic of both a bygone time and the promise the future held during that time, a past-future when it was possible to go anywhere and be anyone. The neon, too, has its own retro connotations, more sock-hop than Beaux-Arts. They don’t match up.

The combination makes sense only in the context of the film-Jasper’s crazy-quilt approach to authenticity. This is a town of bearded old codgers who raise horses, and also have expensive faux-rustic loft apartments in their barns, located directly across the water from mansions with property big enough for helicopters to land on. It’s the home of countrified fellas named Red who run small auto-parts stores and huge Ford card dealerships, both of which are held up to be models of small-business entrepreneurship against Brad Wesley’s chain-store depredations. It’s a place where one dive bar out of several that we visit can be the stomping ground of a clientele straight out of The Road Warrior one month and a mecca for nightclubbers who pay top dollar to see a blind white boy play the blues the next, predicated on the garish design sensibilities of the bar’s rich owner and the ability of the bar’s cooler to settle all problems in the town with violent force.

And you know that “main thoroughfare” bit? Who knows! I basically made that up, since we never see this place nor anywhere remotely like it ever again. This crowded stretch of commercial development with decent walkability and the network of dirt roads, junkyards, and greasy-spoon diners the rest of the movie traverses have about as much in common as, well, the clock and the neon sign. But each stretch of road broadcasts realness.

Dalton intuits this, which you can see in the way he self-effaces regarding his fancy degree from New York University, but takes the ancient practice of tai chi directly to the shores of Jasper’s lake-river. By turning the sign away from Dalton’s point of view at this early moment, Dalton’s status in the town is left an open question—one quickly answered, true, but that answer is earned. Dalton is welcome in Jasper.

Brad Wesley talks a good game about small-town values and that old time rock and roll, but everything else about him—riding in a chopper, erecting malls, interacting with nature primarily by killing, stuffing, and mounting wild animals from around the world rather than the good ol’ USA—does not. This makes him an interloper, an occupier, a colonizer, someone as out of place in Jasper as a Calvin Klein’s Obsession ad would be below that neon sign and Seth Thomas clockface. Brad Wesley is not welcome in Jasper.

But you are welcome in Jasper, dear viewer. You are welcome here from the start, trusted by the town to take it into your heart in all its complementary contradictions. You must be, because it’s the only way to move forward and drive on to what awaits.

013. Men look at Dalton

January 13, 2019When men look at women in Road House it means trouble. Steve the bouncer ogles his teenage would-be conquests. A husband with a cuckold fetish and a goofball barfly fetishize and fondle his wife’s breasts. A belligerent drunk starts a knife fight when people try to prevent him from watching his girlfriend dance on a table. Brad Wesley throws an absurd string-bikini pool party for his army of goons. A horned-up soldier rushes the stage in the topless bar where Wade Garrett works. Denise strips in front of the Double Deuce’s wolf-whistling bad seeds under Wesley’s approving eye in a strange act of macho-sexual judo. With two exceptions—the superimposition of the film’s title over an anonymous woman’s rear end, echoed by Wade hating to see Doc leave but loving to watch her walk away—the traditional male gaze is an indication that something is wrong.

When men look at Dalton, it’s different. And men look at Dalton alright. All kinds of men, for all kinds of reasons.

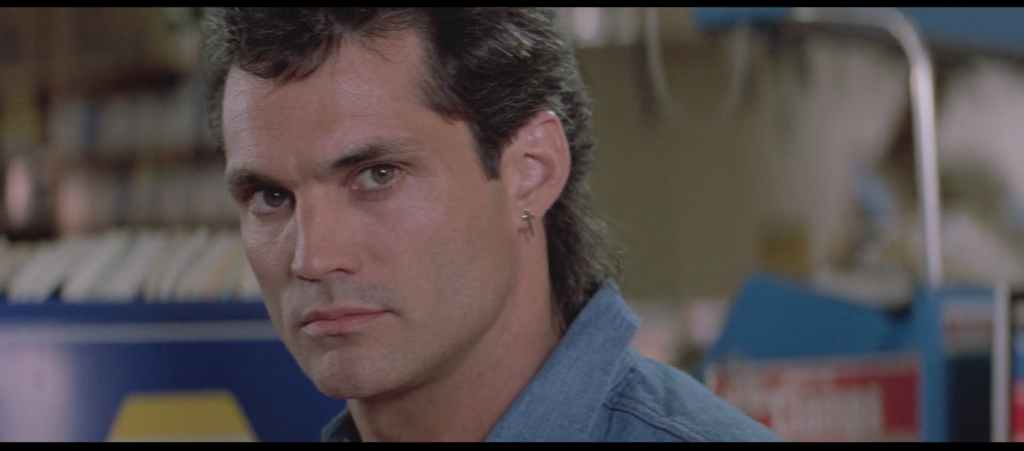

When they first meet, goons like Karpis and Jimmy lock eyes with Dalton in staredowns that sizzle with psychosexual challenge. (In Jimmy’s case the sexual element is made abundantly, infamously clear later on in the film.)

Frank Tilghman stares at Dalton and smiles over and over again, like a man seeing his favorite meal on the way over to his table. “I want you,” he says during one such glance, followed in that same conversation with a knowing “I thought you’d be bigger.” “He’s good. He’s real good,” he says to another man during another. Honestly Tilghman is such a strange character that he probably deserves an essay series of his own, but his open near-worship of Dalton is a start.

Both Dalton’s friendly landlord Emmet and his evil neighbor Wesley watch Dalton perform tai chi, shirtless and slick with sweat. Wesley has the look you often see on the faces of men in movies who’ve caught a glimpse of a topless woman through a window. Emmet looks like he’s questioning a whole lot about the world and his place in it.

Wesley even watches Dalton and Elizabeth have sex. You might think that Elizabeth is the object of the gaze here, but at no other point in the film does Wesley bring her up as a point of contention between himself and Dalton, even though their relationship does seem to catalyze a new level of hostility between the two men. There’s no “she’s mine, if I can’t have her no one will,” and when he talks to her about Dalton it’s to express regret that she’s wound up with a lowlife drifter, not to threaten her to come back to him. He only has eyes for Dalton.

And honestly, who wouldn’t? Look at him.

By constantly showing us men who visually appreciate Dalton, Road House models behavior for its primarily male audience. Which is not to say women were not a target as well. Surely a decision was made to capitalize on the sex symbol status of the man who plays Dalton, Patrick Swayze, for the women in the audience—by then he’d starred in the smash hit Dirty Dancing, and another romantic blockbuster, Ghost, was on the horizon; his sex scene with Kelly Lynch set to Otis Redding beat the pottery scene with Demi Moore set to “Unchained Melody” to the punch.

But Road House‘s life since its theatrical release has been one of basic-cable afternoon screenings for dudes. I myself never caught it that way, but I first saw it during a Road House/The Warriors/The Road Warrior triple feature with a bunch of drunk and high friends, which is more or less the same idiom. I came away from my first viewing feeling just an unbelievable amount of affection and admiration for Patrick Swayze, an actor I’d never really thought about at all before. When he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, I held a Road House/Steel Dawn/Point Break triple feature at my place and charged everyone a twenty-dollar donation to pancreatic cancer research for admission. I love Patrick Swayze just as I love Dalton. I believe these shots of men looking at Dalton, capturing the blend of admiration, envy, desire, and awe they feel when they look at him—call it the male swayz—are, at least in part, the reason why.

010. Denise

January 10, 2019Who is Denise? Denise is Brad Wesley’s girlfriend, and the most stylistically sophisticated and culturally aware human being in the entire film. You can tell this at first glance, and glances are really all you get. Her lines are minimal: She rebuffs a vulgar proposition, makes one of her own, and…that’s it, I realize now. That’s all Denise gets to say.

But she makes an impression, I can tell you that much, and she does so long before she enthusiastically strips on stage at the Double Deuce with Wesley looking on approvingly, some time after he beats her off-camera for coming on to Dalton. Even when the bar looks like it might collapse around her ears at any moment, even when its atmosphere resembles a Tables Ladders and Chairs match more than a nightclub, she’s there with her girlfriends, leader of the pack, out on the town and dressed to kill.

Sure, she attends Wesley’s ludicrous backyard pool party/dance party/orgy/whatever it is. But when he’s not around and she gets her first good look at Dalton, the camera whip-zooms in on her dilated-pupil look of desire like Cupid’s arrow. It’s such a jarring moment in this straightforwardly shot film—easily the most cinematographically adventurous thing that happens—that in any other movie it would indicate the start of a major plotline.

But it goes nowhere beyond her asking Dalton to go to her place and fuck, an offer she cleverly cushions with a rhetorical flourish: “Would you be shocked if I said ‘Let’s go to my place and fuck?'” Yeah, it sounds like the writers don’t understand that “If I said you have a beautiful body, would you hold it against me” is a play on words. But her forthrightness is admirable, as is the fact that she still has her own place and isn’t relying on Wesley’s largesse. Like O’Connor, whom he beats for the crime of bleeding, she knows you can’t count on staying on Brad Wesley’s good side.

By the end of the movie that’s not an issue anymore. Freed from Wesley’s influence and the watchful eyes of his goons, she’d theoretically be able to enjoy more nights out with the girls, in a renewed and revamped Double Deuce that better suits them. But we don’t know. Denise’s final moment in the film is being ridiculed by an uncharacteristically ugly Dalton as a pet that Wesley should keep on a tighter leash. She’s afforded no payback for that slight, or for Wesley’s abuse. Imagine if she’d wielded one of those shotguns instead of, say, Pete Strodenmire, the guy we see in a grand total of one scene before his car dealership gets run over by a monster truck. That would be something, right?

But there’s nothing instead. Awkwardly covering her bare breasts, she gets dragged off stage, off camera, and out of the movie. Freaking Tinker gets a better redemption arc. Still, during that one shot, there’s the promise of a whole world in her eyes—her apartment’s decor, her girls’ nights out, her love for buoyant late-’80s dance pop, her desire for a relationship with Dalton worth risking Wesley’s wrath for, even if it’s only for a night. She is Road House‘s great mystery, its Mona Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam. Who is Denise? We’ll never know. But she’s in there somewhere.

007. Goons

January 7, 2019You can’t make a JC Penney without breaking some eggs. That’s where these fellows come in. Organized crime boss, mall developer, and job creator Brad Wesley employs a small army of goons, thugs, henchmen, minions, and muscle to do his dirty work around the town of Jasper, Missouri. Blowing up an auto parts store, blowing up an old man’s shack, and running over a car dealership with a monster truck are just the most glamorous aspects of the gig: These guys’ main function is to punch people in the face, and get punched in the face in turn. The following is a brief survey of the Wesleyans with speaking parts. You’ll be seeing more of these gentlemen for sure, but this should bring you up to speed.

Morgan

Ornery brute. Originally a bouncer at the Double Deuce. Fired by Dalton because he doesn’t have “the right temperament for the trade.” Doesn’t take it well. Played by pro wrestling legend Terry Funk. Strengths: Looks and acts like a guy who could kick someone’s ass. (Not for nothing did he prompt the “It’s still real to me, dammit!” incident.) Weaknesses: Syllable emphasis.

Pat McGurn

Vicious weasel. Nephew of Brad Wesley. Originally a bartender at the Double Deuce. Fired by Dalton for skimming from the till, sparking the Wesley/Dalton feud. Played by punk legend John Doe. Strengths: Convincingly sleazy mustache. Weaknesses: Uncle’s Boy.

Jimmy

The main man. Wesley’s favorite. Rarely far from his boss’s side. Martial-arts master who fights both Dalton and Wade Garrett to near-standstills. Gets the film’s most famous non-Swayze line: “I used to fuck guys like you in prison!” Played by Marshall Teague. Strengths: Smoldering eyes, witty banter, maniacal laugh, actual fighting skill. Weaknesses: Sore throat.

O’Connor

Middle management. Basso profundo beanpole who leads the expedition to restore Pat to full employment at the Double Deuce, among other crucial tasks requiring minimal competence. Played by Juilliard graduate Michael Rider. Strengths: Business casual wardrobe. Weaknesses: He’s a bleeder.

Tinker

Lummox. Portly core component of the Wesley team. Frequent partner of O’Connor. Partial to trucker hats and suspenders. Played by John Young. Strengths: Comes closer to actually killing Dalton than almost anyone else, inflicting the knife wound that leads to Dalton meeting Dr. Elizabeth Clay; perhaps for this reason he is the only member of the Wesley Organization to find forgiveness and redemption. Weaknesses: Polar bears.

Mountain

The tallest. Towering doofus who serves primarily to dance amusingly during Wesley’s pool party and engage in brief but memorable dick-based repartee with Sam Elliott. Played by Check It Out! with Dr. Steve Brule fry cook Tiny Ron. Strengths: Hell of a dancer, very tall. Weaknesses: “Give me the biggest guy in the world: You smash his knee, he’ll drop like a stone.”

Ketchum

Serious business. Wesley’s most all-American thug. Trusted with the most hardcore tasks. Almost entirely forgettable despite performing several of the film’s greatest acts of villainy unless you’ve seen the movie enough to write about it every day for a year. Played by stuntman Anthony De Longis. Strengths: boot-mounted knife, regular knife, monster truck. Weaknesses: …wait, who are we talking about again?

Karpis

Man of mystery. Piercingly handsome guy in a smart-looking suit worn with rakish dishevelment. Present in background when Wesley’s chopper lands during the character’s introudction. Present in background when Wesley throws a pool party. Wordlessly witnesses Wesley’s punishment of O’Connor for failing to secure Pat’s job. Tosses Red Webster’s store to keep him in line and says “Life is good” as his one line. Vanishes completely from the film after these four scenes. Lives forever in my heart. Played by Joe Unger, aka Sgt. Garcia from A Nightmare on Elm Street. Strengths: Looks like he plays rhythm guitar for Dr. Feelgood or the Strokes circa the $2 Bill show, dangerously sexy. Weaknesses: Barely in the movie, named “Karpis.”

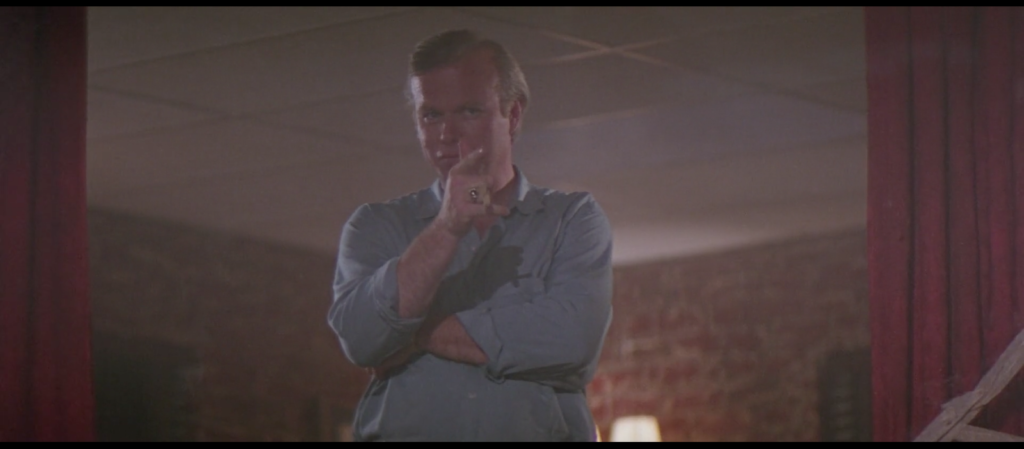

002. Brad

January 2, 2019 Here’s what we know about Brad Wesley.

Here’s what we know about Brad Wesley.

He grew up on the streets of Chicago, where he “came up the hard way.”

He came to Jasper, Missouri after serving in the Korean War.

His grandfather was an asshole.

He has one sister, whom we don’t meet.

He has a nephew, Double Deuce bartender Pat McGurn, whom we do.

He has a cousin in Memphis. (This unseen—or is he?—cousin tells him Dalton killed a man down there. Said it was self defense, which Brad doubts.)

He owns a helicopter, an ATV, a red convertible, and a monster truck, all of which he enjoys driving, or paying someone else to drive, erratically.

He loves the song “Sh-Boom.” (The Crew Cuts version, not the Chords version, which if you know Brad is unsurprising.) He can’t stand today’s music, which has “got no heart.” He prefers when bands “play something with balls.”

He employs a squad of goons for whom he enjoys throwing topless poolside bacchanals, and whom he also enjoys beating up arbitrarily when they displease him for reasons such as bleeding too much.

His favorite goon is Jimmy, a martial artist who I believe to be his bastard son. Strictly speaking this is not supported by the text—Wesley refers to all of his goons as “my boys”—but it’s in the eyes.

He’s “dating” a woman named Denise, whom he beats up for coming on to our hero Dalton. Later he has her do an erotic striptease at the Double Deuce to teach Dalton a lesson (?).

He used to be married to Dr. Elizabeth Clay, a surgeon or gastroenterologist with whom Dalton becomes involved after she treats him for several wounds incurred in his first barfight at the Double Deuce.

He lives in a waterfront mansion across a lake or river or something from the farm or ranch or whatever where Dalton rents an extravagantly appointed open-air apartment from a bearded old codger named Emmet who sleeps in a union suit. This provides him with a convenient vantage point from which to buzz the old man’s horses with his chopper or sit in a rocking chair and watch Dalton and Elizabeth have sex on the roof of a barn.

Now’s a good time to mention he’s played by Ben Gazzara, a frequent collaborator of John Cassavetes who created the role of Brick in the original Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

He alternates between light-colored suits of the Boss Hogg variety and the fussily sporty apparel of a weekend warrior. As they do in the wardrobes of many characters in this film, boots play a disproportionately large role in his ensembles.

He has a trophy room full of the stuffed carcasses and mounted heads of both exotic and domestic animals that would shame a Trump son.

He runs a glorified protection racket called the Jasper Improvement Society that keeps all the local businesses under his thumb, including the auto parts store run by Elizabeth’s uncle Red Webster.

He controls alcohol distribution in the region, which provides him with a line of attack on the Double Deuce after his nephew Jimmy is fired for skimming the till.

He feels that his many achievements in building the town of Jasper up from “nothing” have entitled him to get rich off its inhabitants.

Here are those achievements, quoted verbatim.

I brought the mall here. I got the 7-Eleven. I got the Fotomat here. Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me! You ask anybody, they’ll tell you!

Road House is the story of one bouncer’s quest to free a small town from the iron fist of the guy who is on the verge of opening the area’s first JC Penney. Over half a dozen men will die for this.