Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

So that tells you something about the kind of film Road House is: It respects the people who beat up people who beat up other people in bars so much that it affords them significant renown. Other men will fly across the country and offer these men hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for their services. Barfolk, for want of a better term, whisper their names in reverent awe. In the land of the blockheaded, the two-fisted man is king.

Because their reputations precede them, or because to invoke them inaugurates the ritually contracted cycle of redemptive violence for which they’ve been hired, the bouncers of Road House are reluctant to share their names.

“You got a name?” asks Carrie Ann, waitress at the Double Deuce, the ultraviolent Missouri honky-tonk at the heart of the story. “Yeah,” answers our hero.

“What’s your name, buddy?” asks Pat, the Double Deuce’s thieving failnephew bartender, who is played by John Doe of Los Angles punk institution X. “Coffee, black,” responds our hero.

When he conducts his first official bouncing during his tenure at the Double Deuce by smashing the face of a man with a switchblade and a Hawaiian shirt through a table adjacent to the one on which this man’s girlfriend has been dancing and thus lowering the overall atmosphere of class in the establishment, it falls to our hero’s blind white blues-playing guitarist friend Jeff Healey (appearing as himself) to reveal his identity to the amazed, and in several cases visibly aroused, patrons.

“The name,” he says, “is Dalton.”

Dalton is by this point in the film known to the Double Deuce’s staff, over whom he’s been given absolute authority by the bar’s bizarre owner Frank Tilghman. “What he says? Goes,” Tilghman tells his employees.

“It’s my way or the highway,” Dalton concurs.

The first person to learn his identity other than Tilghman himself is Carrie Ann, who powers through our hero’s extremely badass rebuff as described above and gets him to name himself, the way Superman tricks his gnomish extradimensional enemy Mr. Mxyzptlk into saying his own name backwards to eliminate him. (Carrie Ann has no such goal, of course; it is perhaps for this reason that she is rewarded later in the film with a glimpse of our hero in the nude. to which she reacts with slackjawed lust so powerful, courtesy of actor Kathleen Wilhoite, that it all but glows with its own internal erotic energy.)

“Shit,” Carrie Ann says when Dalton reveals himself. “I heard a’ you!”

The news spreads like wildfire through the waitstaff, bartenders, and bouncers already in the Double Deuce’s employ, none of whom need its import explained to them. Like I said, a famous bouncer’s reputation precedes him. One man has heard he ripped a guy’s throat out with his bare hands. Another has heard he has balls big enough to come in a dump truck. “Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name,” runs the song from another artifact of Eighties bar culture. Dalton can go anywhere.

Which gives us some indication of his exact level of fame. No one at the Double Deuce recognizes him on sight, which means he’s not so famous that his face alone writes his ticket for him. However, the moment he says “Dalton” in response to Carrie Ann’s query, she immediately assumes he is the Dalton famous for being a bouncer, and not any of the other myriad possible Daltons in the world—B. the bookseller, for example. It’s as if she asked a woman who was new to the Double Deuce for her name, and that woman replied “Gaga.” Only one person leaps to mind.

This separates our hero from his hero. “Wade Garrett’s the best,” Dalton tells Tilghman when the Missouri restaurateur says he’s heard he, Dalton, is the best. “Wade Garrett’s getting old,” Tilghman replies. But age has not dimmed his starpower. Arguably, age is responsible for it. The longer he’s been out there, bouncing and cooling, the more time the dive-bar demimonde has had to put a face to the name.

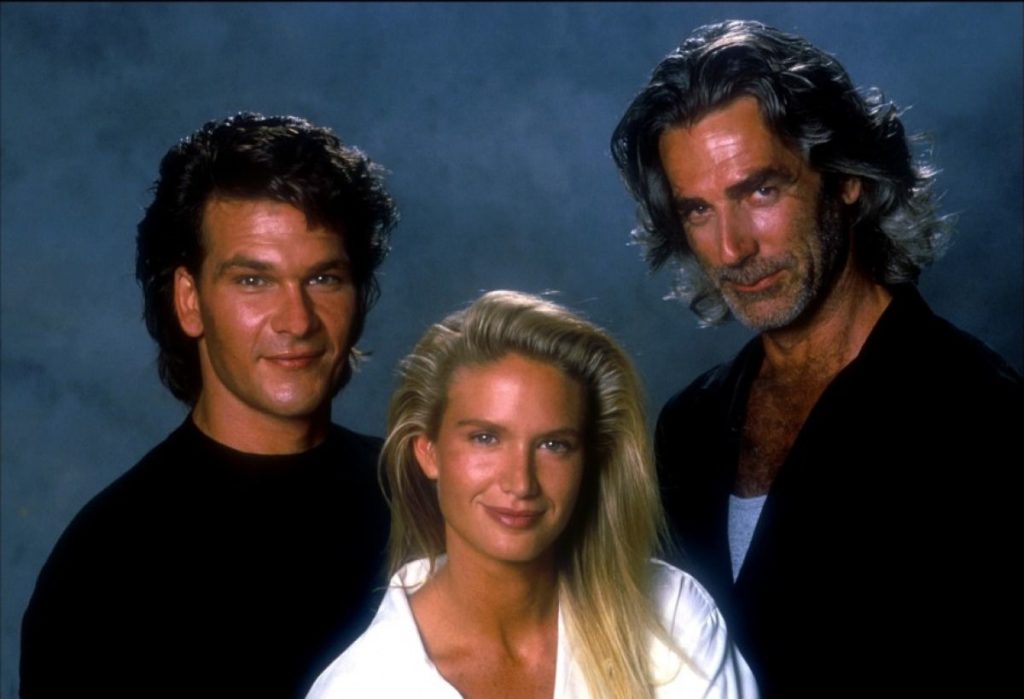

The face belongs to Sam Elliott, who in this film has long greasy hair, tight black jeans, five o’clock shadow that creeps up his face nearly to his eyes, and a grizzled sexuality that wafts from the screen like a musk. When he arrives at the Double Deuce to help his one-time protégé Dalton defend the establishment against the depredations of Brad Wesley, a local business tycoon and J.C. Penney franchisee played by Ben Gazzara (The Killing of a Chinese Bookie), no one asks his name, because no one needs to. Practically the entire staff stares at him with the wide eyes of children in a film directed by Chris Columbus when he limps bowleggedly into the place looking for his mijo.

Grinning slyly, his eyes twinkling with a sinister delight that seems to be actor Kevin Tighe’s natural mien and has no basis within the character itself, Tilghman looks at this man and says, “I know you.”

Wade Garrett, it can be concluded, has achieved a level of fame so total that even people steeped enough in bouncer culture to know Dalton by name know him by sight. Michael Jordan fame. Michael Jackson fame. Santa Claus fame. Wade Garrett is the best, Dalton tells us. And when Dalton speaks, we would do well listen. It’s his way or the highway. What he says? Goes.

Directed by Rowdy Herrington, written by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin (Academy Award winner, Wag the Dog), released in 1989, directed by Rowdy Herrington (the name bears repeating), and starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara, and an assortment of people with anywhere between one to six lines of dialogue all of whom I adore completely, Road House is one of my favorite movies ever made. I like to talk about it. I hope you’ll like to listen.