I want to tell you a story of a man and his bleeder.

The man is Brad Wesley—sportsman, outdoorsman, liquor distributor, civic leader, JC Penney franchisee. The bleeder is O’Connor, the goon upon whom Brad Welsey’s disfavor falls, to his great misfortune.

The scene in which Wesley beats O’Connor, ostensibly for failing to defeat his newfound enemy Dalton and restore his nephew Pat McGurn to his position as bartender at the Double Deuce but for the stated reason that O’Connor bleeds too much (?????????), is a fanmaker. It’s up there with the first deck-clearing barfight, the realization that Dalton visits four separate salesmen of cars and/or car parts, the Giving of the Rules, Doc’s Dress from an Italian Restaurant, “pain don’t hurt,” you name it. It’s even more of a fanmaker if you are, as you should be when you watch Road House, fucked up. It whipsaws back and forth from one emotion to its diametric opposite so fast and so often that it makes you feel fucked up whether you are or not. Only the lag time in comprehension caused by chemical intoxication comes close to replicating the Bleeder Scene’s otherwise inimitable psychological Gravitron.

We’re going to take it frame by frame.

The goons roll up to Brad Wesley’s mansion. Among them are Pat McGurn, Tinker, and O’Connor, the three men defeated by Dalton and his bouncers at the Double Deuce the previous night. Ketchum and Karpis, who are never referred to by name in the film, arrive separately in the monster truck.

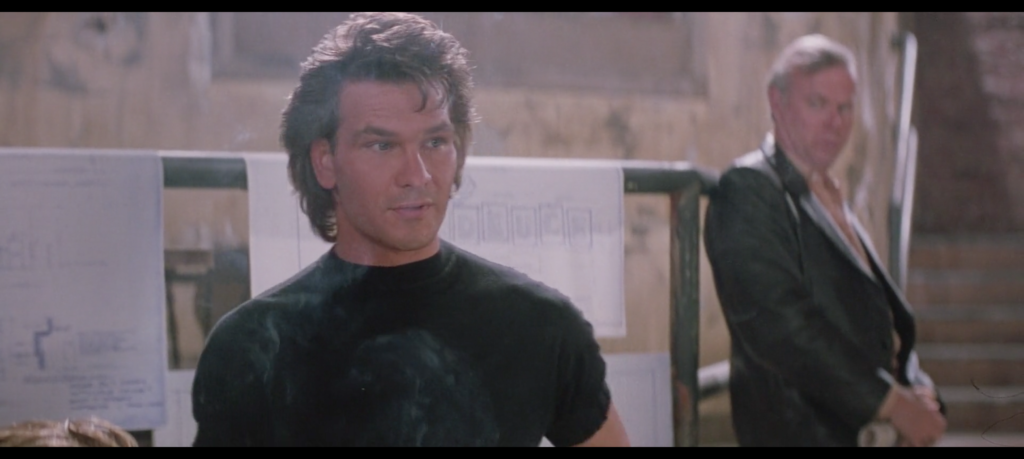

Wesley and his right-hand man Jimmy exit his mansion to greet their visitors. Wesley is holding a half-smoked cigar. Jimmy puts on his shades. Wesley sighs with exasperation. Wordlessly and shamefacedly, Pat skulks past them into the mansion himself.

Wesley smiles sardonically.

[Tone: disapproving irony]

WESLEY: Did I explain it wrong? Is that it?

O’CONNOR: No boss, you didn’t.

[Tone: pity for Pat, with a hint of condescension]

WESLEY: Pat’s got a weak constitution. You boys know that. That’s why he’s working as a bartender.

[Tone: righteous familial fealty]

He’s my only sister’s son. And if he doesn’t have me, who’s he got?

[Tone: just the facts about the job]

And If I’m not there, you’re there.

Wesley affectionately grabs Jimmy by the back of the neck.

[Tone: mixed admiration for his favorite son and regret for his own lack of perspicacity]

Shoulda let you go, Jimmy.

Wesley begins circling the assembled goons.

[Tone: Disappointed schoolmarm]

Well, one of you boys owes me an apology. Now I’ll leave it up to you to decide which one of you wants to say “I’m sorry.”

TINKER (contritely removing trucker hat): ’m sorry, boss.

O’CONNOR: I’m sorry, boss.

[Tone: forgiving father figure]

WESLEY: I believe you, Tinker.

[Tone: mounting suspicion]

But you, O’Connor, somehow I don’t believe you.

[Tone: assistant manager who really doesn’t want to have to report this to corporate]

Now you better try it again, because if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s a man who’s untruthful.

O’CONNOR: I’m sorry, boss.

[Tone: fast-burning anger]

WESLEY: And if there’s one thing that disgusts me, it’s a man who can’t admit when he’s wrong.

O’CONNOR: I swear to God, boss, I’m sorry.

[Tone: pure hate]

WESLEY: You disgust me, O’Connor. You wanna know why you disgust me?

O’CONNOR: No, why, boss?

Wesley punches O’Connor in the face, causing his nose to bleed. O’Connor feels the blood and looks at his boss, confused.

[Tone: cheerful scientific observation]

WESLEY: ’Cuz you’re a bleeder. You bleed too much.

[Tone: the kind of contempt that ends with kneeing someone in the balls]

You are a messy bleeder.

Wesley knees O’Connor in the balls. O’Connor doubles over.

[Tone: pure disappointment]

You’re weak.

[Tone: prepping for a Quod Erat Demonstrandum]

You got no endurance for pain.

On “pain,” Wesley slams his fist down onto the back of O’Connor’s head, knocking him to the ground.

Wesley looks at the other goons, who are all smiling happily at the unfolding events, with “what did I tell you” grin that rapidly fades. He pats the crumpled O’Connor on the back.

[Tone: stern but ultimately kind tough-love football coach]

Now come on. Get up.

[Tone: ER doctor on a double shift talking to a drunk patient who cut his forehead after walking into a lamppost]

Yeah you’ll be fine. Come on.

O’Connor tries to stand and falls even flatter. Wesley looks around at his goons.

[Tone: “Do I have to do everything around here?”–style fed-up fury]

Well help him up!

Ketchum and Jimmy lift the dazed O’Connor to his feet.

[Tone: enough with the pity party]

You’re gonna be fine.

Wesley smiles benevolently. He puts his hand on O’Connor’s shoulder.

[Tone: “I’m not just your boss. I consider us a family.”]

And you know why? Because I like you.

O’Connor smiles, glad to be forgiven. Wesley socks O’Connor right in the jaw, knocking him out cold. Wesley addresses his goons as he turns to go back inside.

[Tone: scraping cat turds off his shoe]

Get this piece of shit coward outta here.

The Bleeder Speech contains every feeling possible to express in its idiom. It is the White Album of ‘80s action-movie bad guy speeches. Brad Wesley is the Fab Four (and Eric Clapton on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”), and the Bleeder is his muse—the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, John Lennon’s mom, Paul McCartney’s dog, Yoko Ono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ringo Starr quitting and fleeing to a boat in Sardinia for a few weeks, and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi all rolled into one, wrapped in a short-sleeved dress shirt, and beaten up in a driveway with a monster truck parked in it.