The Death of Superman

Dan Jurgens, Jerry Ordway, Louise Simonson, Roger Stern, writers

John Bogdanove, Tom Grummett, Jackson Guice, Dan Jurgens, Brett Breeding, Rick Burchett, Doug Hazlewood, Dennis Janke, Denis Rodier, artists

DC, 1993

168 pages

$9.99

Buy it from Amazon.com

Nostalgia is an occupational hazard for comics readers. Even as I write this, there’s a part of me that wonders how much of what I’m about to say is colored by the mere fact that I first read this material not as a 31-year-old, but as a 14-year-old, with a 14-year-old’s understanding of the industry and artform of comics. But honestly? I’m thinking “not much,” because the 31-year-old likes this comic a lot more than the 14-year-old did.

For example, back then I was deeply unimpressed by the motley crew of losers who made up the Justice League at the time, and who were really the stars of the show in the initial issues of this storyline. They’re a parade of weak designs and goofy powers, from Guy Gardner’s bowl haircut and leather jacket to Blue Beetle’s beetle-shaped spaceship Booster Gold’s superpowered spandex outfit to a character named Fire who is inexplicably green, not, you know, fire-colored. At least Ice looks icy. There’s some B-plot mystery involving a ’90s-tastic goofball named Bloodwynd (look at that ‘y’!) whose word balloons drip blood, there’s a woman warrior named Maxima who is to other, better superheroines like Wonder Woman and Phoenix what one of those cheapo greatest-hits collections you can get in a five-dollar bin at the grocery store is to the overall recording career of Johnny Cash…Man, do these guys suck.

Superman himself fared little better with me. I mean, he’s Superman, he has that going for him, which is nice. But what a square, boring world he inhabited at the time! The first issue collected here sees him face off against a bunch of underground monsters who talk like Cookie Monster and present just about as much of a convincing threat. There’s the usual horrible street-dialect comics writers of yore subjected any blue-collar character to–you know, “ta” instead of “to” and a lot of “in'”s instead of “ings.” Gross. Finally, Superman’s big character moment before the action starts is a TV interview in which they reveal a hidden power of his: The ability to avoid saying anything remotely interesting. He offers a politician’s focus-group-tested, studiously bland and inoffensive answers to questions about his role as the obviously most awesome guy in the Justice League, his recent fight with asshole Guy Gardner, the fact that Maxima looks and dresses like a swimsuit model, and so on. If the writers had set out to make him unappealing to teenagers, they couldn’t have done a better job.

And ultimately, 14-year-old me ended up sharing much of the conventional fan wisdom about Superman’s beating death at the hands of the monstrous new enemy Doomsday. Doomsday wasn’t a character, he was a plot device, created for the sole purpose of killing a character who basically couldn’t be killed. (DC would repeat this trick later with Bane and Batman, introducing a huge dude to beat the unbeatable hero.) Lex Luthor got gypped. It wasn’t a story, it was a mere slugfest, not the Shakesperean tragedy that would befit such a momentous occasion. Though I hadn’t read any of them other than The Dark Knight Returns, I was aware of the medium’s artistic masterpieces, such as Watchmen, Crisis on Infinite Earths, and Camelot 3000–did not Superman deserve a send-off of their caliber? Finally, by the time the hype died down, Superman came back to life with long hair (remember, no one used the m-word back then), and it became apparent that my multiple unopened polybagged copies of the actual death issue weren’t going to be putting me through college, I just plain felt ripped off. Instead of six copies of the Death of Superman comic, I wished I bought just one of that awesome Death of Superman t-shirt.

That last part I still agree with. The rest? Oh, to be that young and naive again! Because I’ll tell you what–I wish we could get an event comic as rollickingly entertaining as The Death of Superman today.

Viewed with some distance, read in the comfort of my marital bed rather than my parents’ basement, stacked up against the many many many many comics I’ve read since then, I find that most of my teenage complaints are flipped on their head. Okay, so the dialogue stinks, there’s really no bones to be made about that. (Seriously, people give Bendis a hard time over his tics, I know, but superhero comics have truly seen a quantum leap in the craft of creating believable, entertaining human speech.) But take that crappy Justice League (please!): It’s their very crappiness that makes the book so entertaining in its early going, when the action consists of nothing more or less than Doomsday pounding them into unconsciousness over and over again. If I recall correctly, Doomsday’s rampage effectively ended this era of the team, a consummation devoutly to be wished. It’s a perfect blending of an in-story plot with a meta need, i.e. to lose these losers. I could read page after page of Blue Beetle lying prone on a pile of rubble begging for help or Maxima getting tossed around like a sack of potatoes and never ever get tired of it.

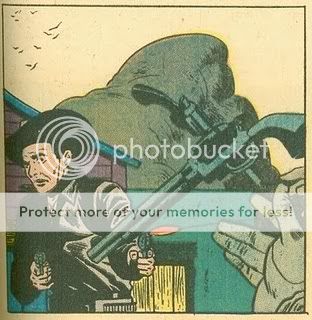

And page after page of people getting the stuffing knocked out of them is exactly what you get, which leads to my next point: An action-comics event consisting almost entirely of action is a great idea, but as we’ve recently learned, it can be difficult to convincingly pull off if all you do is have big spreads with dudes shooting lasers in all directions in the middle of nowhere, punctuated by approximately one memorable action beat per issue. In The Death of Superman, laser blasts are kept to a minimum, and when they’re fired, they’re all pointed in one direction at one guy: Doomsday, who just stands there and takes it. Most of the rest of the action is fisticuffs, a pure slobberknocker. Doomsday has a simple goal: Keep moving and keep destroying. Superman and friends have a goal that’s just as simple: Stop him. In that basic set-up we have a sense of directionality, a readily understandable concept of what victory or defeat for either side looks like, and a simple way to root the combat in the immediate physical presence of the combatants.

I’m also now struck by how smartly staged the action can get. Doomsday’s less a villain than your basic rampaging monster, and thus the creative team sets him loose in time-tested rampaging-monster fashion, having him smash his way through everyday environments like a highway, a Wal-Mart, a suburban neighborhood. You picture something like this happening near where you live and quickly get a sense of how friggin’ cool it would look. In addition, Doomsday’s always moving, which gives the fight a propulsive momentum, but when he does get bogged down for a time by Superman or the Justice Losers, the creators make skillful use of that particular place–in the suburbs, a single mother bickers with her teenage son until Doomsday lobs a knocked-out superheroine through their kitchen window and eventually lights the whole house on fire; near the headquarters of the Jack Kirby-created Cadmus Labs, Superman and Doomsday fight in a giant technoorganic Ewok village whose treelike structures they bring clattering down like Lincoln logs; the final stage of the fight is just a bareknuckle brawl in the middle of the street outside the Daily Planet, which location they quickly reduce to a slag heap. In each case, you get a sense of where you are and what’s happening to it. Action has consequences.

Doomsday himself, moreover, is a great design. In the comic, he starts out in an all-over green jumpsuit and mask, festooned with looping binders, that obscures his bony spikes and monstrous face. He looks like a square-bodied Kirby creation run amok. But as the fight progresses, his outfit is torn away, revealing the very ’90s everything-more-awesome-than-everything-else spikes and claws and so on we’ve come to know. One of those allegorical Kurt Busiek/Alex Ross/Brent Anderson Astro City character designs couldn’t have done it better. Superman’s thoughts throughout the fight are a stand-in for our own: a dawning realization that yeah, this guy could succeed where everyone else failed.

In the end, that success (albeit pyrrhic–Doomsday “dies” too) comes suddenly. The final four issues of the story famously “counted down” from four panels per page to three to two, until in the climactic issue the story is told entirely through splash pages. What’s exciting about this to me now is that it’s hard to imagine a comic doing that today, simply because splash pages aren’t storytelling devices, they’re pin-ups and future original art sales revenue. But the Jurgens/Breeding team actually does things with those one-panel-per-page images other than “here, look at this awesome pose!” They awkwardly shift Superman’s body around: For every shot in which he’s flying menacingly at the viewer, there are several more where he’s being hurled into a helicopter, or where he slams into his opponent upside-down, or where he’s driven by his feet headfirst into the concrete. The angle shifts dramatically as well, and the bold transitions–from a worm’s-eye-view behind Doomsday’s legs to a medium shot of Doomsday from the front getting punched in the back to a ten-feet-overhead view looking straight down at Superman as he heat-visions Doomsday into the side of a building, for example–create an unpredictable, gripping flow. On the page in which the two fighters ready what will be their final blows, there are no grand gestures or profound interior monologues; the last thing Superman thinks before receiving a mortal injury is just “I’ve got to put this guy away while I still can!” (“This guy”!) Yeah, it’s a little awkward that the tableaux of grief with which we are presented are Ma and Pa Kent, Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen, and…Bloodwynd and Ice, but the melodrama of that final image–Lois crying to the heavens with her hands twisted into tense claws, Superman lying stretched-out and slack-jawed in the rubble, his tattered cape fluttering off of some nearby rebar like a flag, Jimmy snapping one last photo (from the rear, but I assume he got the angle right eventually)–is a miniature model of body language, jagged edges, and superhero spectacle. And hey, lookit that–that’s not a bad way to describe the whole book.

And when you sit and read it all at once, it’s not even incoherent–it’s just like a constant stream of rad shit hitting your eyeballs, and provided you have the kind of brain equipped to file away genre arcana and recall it as necessary, it flows from one thing into the next with the clarity and purpose of a freight train. Artist Doug Mahnke is an indispensable part of why this works. Mahnke rapidly ascended into my half-dozen or so favorite contemporary superhero artists over the course of his past three major projects; his segue from Final Crisis/Superman Beyond to these key Blackest Night tie-ins is arguably the first smooth transition from one project to another that any of DC’s event-comics artists have pulled off. (Seriously, Rags Morales, Phil Jimenez, J.G. Jones, and Carlos Pacheco all disappeared from DC after their star turns.) What makes him such a good fit here is both his proficiency with horror and monster-movie imagery (standout moments include Black Lantern Abin Sur using his ring to create a ravenous horde of giant floating disembodied black skulls, like he’s Stardust the Super-Wizard or something, and the way he paced Parallax’s fight with the Godzilla-sized Black Lantern Spectre to interrupt Orange Lantern Luthor’s tussle with Orange Lantern Larfleeze with the fall of one mighty foot) and the way his thick line, emboldened by inker Christian Alamy, holds the bright colors that the material demands. The funny thing is that the “dudes zapping dudes in all different directions” fight un-choreography I always complain about when I see it in ’90s X-Men books or contemporary Avengers titles is inherent to how these characters operate, but Mahnke’s visual imagination and ability to harness those effects and make them feel consequential rather than full of sound and fury but signifying nothing gets them over as involving battles anyway. This storyline–especially when read divorced from the larger plot points of Blackest Night with which it intertwines–is one of the great gonzo thrills provided by genre comics right now.

And when you sit and read it all at once, it’s not even incoherent–it’s just like a constant stream of rad shit hitting your eyeballs, and provided you have the kind of brain equipped to file away genre arcana and recall it as necessary, it flows from one thing into the next with the clarity and purpose of a freight train. Artist Doug Mahnke is an indispensable part of why this works. Mahnke rapidly ascended into my half-dozen or so favorite contemporary superhero artists over the course of his past three major projects; his segue from Final Crisis/Superman Beyond to these key Blackest Night tie-ins is arguably the first smooth transition from one project to another that any of DC’s event-comics artists have pulled off. (Seriously, Rags Morales, Phil Jimenez, J.G. Jones, and Carlos Pacheco all disappeared from DC after their star turns.) What makes him such a good fit here is both his proficiency with horror and monster-movie imagery (standout moments include Black Lantern Abin Sur using his ring to create a ravenous horde of giant floating disembodied black skulls, like he’s Stardust the Super-Wizard or something, and the way he paced Parallax’s fight with the Godzilla-sized Black Lantern Spectre to interrupt Orange Lantern Luthor’s tussle with Orange Lantern Larfleeze with the fall of one mighty foot) and the way his thick line, emboldened by inker Christian Alamy, holds the bright colors that the material demands. The funny thing is that the “dudes zapping dudes in all different directions” fight un-choreography I always complain about when I see it in ’90s X-Men books or contemporary Avengers titles is inherent to how these characters operate, but Mahnke’s visual imagination and ability to harness those effects and make them feel consequential rather than full of sound and fury but signifying nothing gets them over as involving battles anyway. This storyline–especially when read divorced from the larger plot points of Blackest Night with which it intertwines–is one of the great gonzo thrills provided by genre comics right now.