Posts Tagged ‘Top Shelf’

Scary

November 1, 2012I’m very happy to say that Tom Spurgeon included three of my comics in his Halloween horror-comics blowout at The Comics Reporter yesterday: “The Real Killers Are Still Out There,” “A Real Gentle Knife,” and Cage Variations. If you haven’t read them before, and you’re still in a Halloween mood, and real life hasn’t been creepy enough for you lately, maybe now’s a good time.

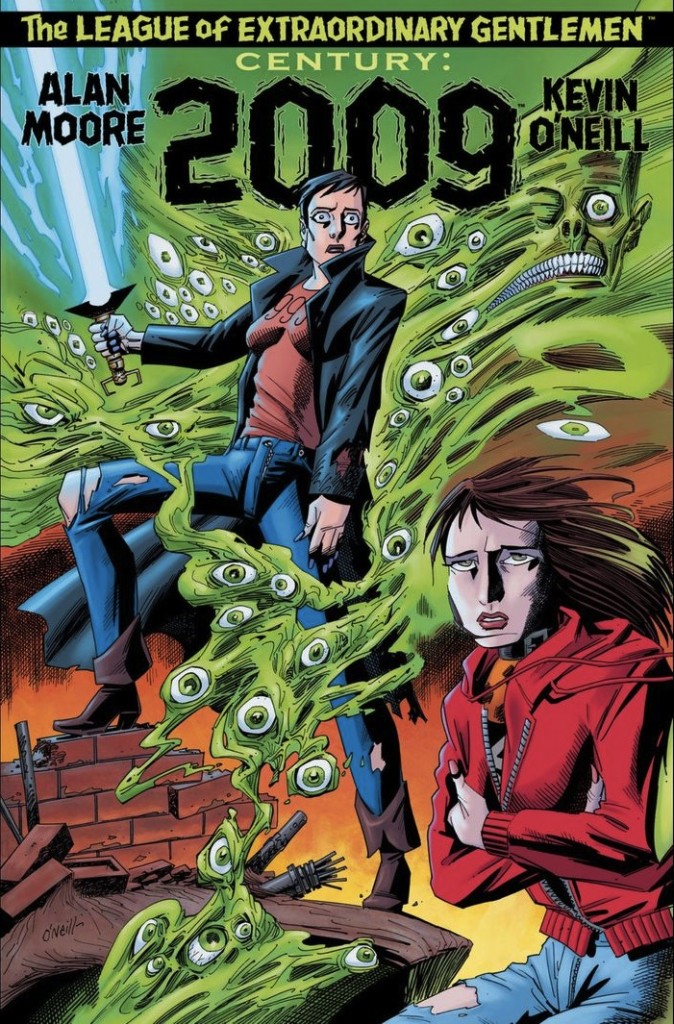

Comics Time: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. III: Century #3: 2009

July 2, 2012The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. III: Century #3: 2009

Alan Moore, writer

Kevin O’Neill, artist

Top Shelf/Knockabout, June 2012

80 pages

$9.95

Buy it from Top Shelf

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

The 20 Best Comics of 2011

January 1, 201220. Uncanny X-Force (Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña, Marvel): In a year when the ugliness of the superhero comics business became harder than ever to ignore, it’s fitting that the best superhero comic is about the ugliness of being a superhero. Remender uses the inherent excess of the X-men’s most extreme team to tell a tale of how solving problems through violence in fact solves nothing at all. (It has this in common with most of the best superhero comics of the past decade: Morrison/Quitely/etc. New X-Men, Bendis/Maleev Daredevil, Brubaker/Epting/etc. Captain America, Mignola/Arcudi/Fegredo/Davis Hellboy/BPRD, Kirkman/Walker/Ottley Invincible, Lewis/Leon The Winter Men…) Opeña’s Euro-cosmic art and Dean White’s twilit color palette (the great unifier for fill-in artists on the title) could handle Remender’s apocalyptic continuity mining easily, but it was in silent reflection on the weight of all this death that they were truly uncanny.

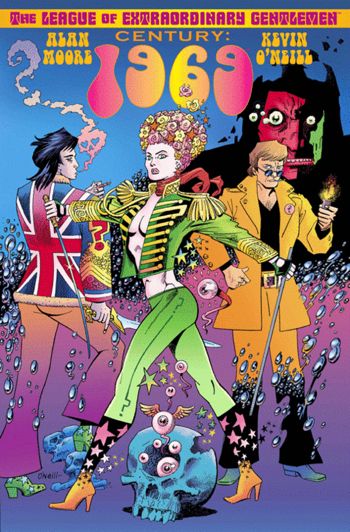

19. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969 (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, Top Shelf/Knockabout): I’ll admit I’m somewhat surprised to be listing this here; I’ve always enjoyed this last surviving outpost of Moore’s comics career but never thought I loved it. But in this installment, Moore and O’Neill’s intrepid heroes — who’ve previously overcome Professor Moriarty, Fu Manchu, and the Martian war machine — finally succumb to their own excesses and jealousies in Swinging London, allowing a sneering occult villain to tear them apart with almost casual ease. It’s nasty, ugly, and sad, and it’s sticking with me like Moore’s best work.

18. The comics of Lisa Hanawalt (various publishers): As I put it when I saw her drawing of some kind of tree-dwelling primate wearing a multicolored hat made of three human skulls stacked on top of one another, Lisa Hanawalt has a strange imagination. And it’s a totally unpredictable one, which is what makes her comics – whether they’re reasonably straightforward movie lampoons or the extravagantly bizarre sex comic she contributed to Michael DeForge and Ryan Sands’s Thickness anthology, as dark and damp as the soil in which its earthworm ingénue must live – a highlight of any given day a new one pops up.

17. Daybreak (Brian Ralph, Drawn and Quarterly): Fort Thunder’s single most accessible offspring also proves to be its bleakest, thanks to an extended collected edition that converts a rollicking first-person zombie/post-apocalypse thriller into a troubling meditation on the power of the gaze. Future artcomics takes on this subgenre have a high bar to clear.

16. Habibi (Craig Thompson, Pantheon): It’s undermined by its central characters, who exist mainly as a hanger on which this violent, erotic, conflicted, curious, complex, endlessly inventive coat of many colors is hung. But as a pure riot of creative energy from an artist unafraid to wrestle with his demons even if the demons end up winning in the end, Habibi lives up to its ambitions as a personal epic. You could dive into its shifting sands and come up with something different every time.

15. Ganges #4 (Kevin Huizenga, Coconino/Fantagraphics): Huizenga wrings a second great book out of his everyman character’s insomnia. It’s quite simple how, really: He makes comics about things you’d never thought comics could be about, by doing things you never thought comics could do to show you them. Best of all, there’s still the sense that his best work is ahead of him, waiting like dawn in the distance.

14. The Congress of the Animals (Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics): The potential for change explored by the hapless Manhog in last year’s Weathercraft is actualized by the meandering mischief-maker Frank this time around. While I didn’t quite connect with Frank’s travails as deeply as I did with Manhog’s, the payoff still feels like a weight has been lifted from Woodring’s strange world, while the route he takes to get there is illustrated so beautifully it’s almost superhuman. It’s the happy ending he’s spent most of his career earning.

13. Mister Wonderful (Daniel Clowes, Pantheon): Speaking of happy endings an altcomix luminary has spent most of his career earning! Clowes’s contribution to the late, largely unlamented Funny Pages section of The New York Times Magazine is briefly expanded and thoroughly improved in this collected edition. Clowes reformats the broadsheet pages into landscape strips, eases off the punchlines and cliffhangers, blows individual images up to heretofore unseen scales, and walks us through a self-sabotaging doofus’s shitty night into a brighter tomorrow.

12. The comics of Gabrielle Bell (various publishers): Bell is mastering the autobiography genre; her deadpan character designs and body language make everything she says so easy to buy – not that that would be a challenge with comics as insightful as her journey into nerd culture’s beating heart, San Diego Diary, just by way of a for instance. But she’s also reinventing the autobiography genre, by sliding seamlessly into fictionalized distortions of it; her black-strewn images give a somber, thoughtful weight to any flight of fancy she throws at us. What a performance, all year long.

11. The Armed Garden and Other Stories (David B., Fantagraphics): Religious fundamentalism is a dreary, oppressive constant in its ability to bend sexuality to mania and hammer lives into weapons devoted to killing. But it has worn a thousand faces in a millennia-long carnevale procession of war and weirdness, and David B. paints portraits of three of its masks with bloody brilliance. Focusing on long-forgotten heresies and treating the most outlandish legends about them as fact, B.’s high-contrast linework sets them all alight with their own incandescent madness.

10. Too Dark to See (Julia Gfrörer, Thuban Press): It was a dark year for comics, at least for the comics that moved me the most. And no one harnessed that darkness to relatable, emotional effect better than Julia Gfrörer. Her very contemporary take on the legend of the succubus was frank and explicit in its treatment of sexuality, rigorously well-observed in its cataloguing of the spirit-sapping modern-day indignities that can feed depression and destroy relationships, and delicately, almost tenderly drawn. It’s like she held her finger to the air, sensed all the things that can make life rotten, and cast them onto the pages. She made something quite beautiful out of all that ugly.

9. The comics and pixel art of Uno Moralez (self-published on the web at unomoralez.com): What if an 8-bit NES cut-scene could kill? The digital artwork of Uno Moralez — some of it standard illustrations, some of it animated gifs, some of it full-fledged comics — shares its aesthetic with The Ring‘s videotape or Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie: a horror so cosmically black, images so unbearably wrong, that they appear to have leaked into and corrupted their very medium of transmission. Moralez fuses crosses the streams of supernatural trash from a variety of cultures — the legends and Soviet art of his native Russia, the horror and porn manga of Japan, the B-movies and horror stories of the States, the formless sensation aesthetic of the Internet itself — into a series of images that is impossible to predict in its weirdness but totally unflagging in its sense that you’d be better off if you’d never laid eyes on it. I can’t wait to see more.

8. The comics of Michael DeForge (various publishers): The last time you saw a cartoonist this good and this unique this young, you were probably reading the UT Austin student newspaper comics section and stumbling across a guy named Chris Ware. All four of DeForge’s best-ever comics — his divorced dad story in Lose #3, his shape-shifting/gender-bending erotica in Thickness #2, his self-published art-world fantasia Open Country, and his gorgeously colored body-horror webcomic Ant Comic — came out this year, none of them looking anything at all like anything you could picture before seeing your first Michael DeForge comic. It’s almost frightening to think where he’ll be five years from now, ten years from now…or even just this time next year.

7. The comics and art of Jonny Negron (various publishers): What if someone took Christina Hendricks’s walk across the parking lot and trip to the bathroom in Drive and made an entire comics career out of them? That is an enormously facile and reductive way to describe the disturbing, stylish, sexy, singular work of Jonny Negron, the breakout cartoonist of the year, but it at least points you in the right direction. No one’s ever thought to combine his muscular yet curiously dispassionate bullet-time approach to action and violence, his Yokoyama-esque spatial geometry, his attention to retrofuturistic fashion and style, his obvious love of the female body in all its shapes and sizes, and his ambient Lynchian terror; even if they had, it’d be tough to conceive of anyone building up his remarkable body of work in such a short period of time. Open up your Tumblr dashboard or crack an anthology (Thickness, Mould Map, Study Group, Smoke Signal, Negron and Jesse Balmer’s own Chameleon), and chances are good that Negron was the weirdest, best, most coldly beautiful thing in it. It’s like a raw, pure transmission from a fascinating brain.

6. The Wolf (Tom Neely, I Will Destroy You): Neely’s wordless, painted, at-times pornographic graphic novel feels like the successful final draft to various other prestigious projects’ false starts. It’s a far less didactic, more genuinely erotic attempt at high-art smut than Dave McKean’s Celluloid; a less self-conscious, more direct attempt at frankly depicting both the destructive and creative effects of sex on a relationship via symbolism than Craig Thompson’s Habibi; a blend of sex and horror and narrative and visual poetry and ugly shit and a happy ending that succeeds in each of these things where many comics choose to focus on only one or two.

5. The Cardboard Valise (Ben Katchor, Pantheon): Prep your time capsules, folks: You’d be hard pressed to find an artifact that better conveys our national predicament than Ben Katchor’s latest comic-strip collection, a series of intertwined vignettes created largely before the Great Recession and our political class’s utter failure to adequately address it, but which nonetheless appears to anticipate it. Its message — that blind nationalism is the prestige of the magic trick used by hucksters to financially and culturally ruin societies for their own profit — is delightfully easy to miss amid Katchor’s remarkable depictions of lost fads, trends, jobs, tourist attractions, and other detritus of the dying American Century. He’s the very most funnest Cassandra around.

4. Love from the Shadows (Gilbert Hernandez, Fantagraphics): I picture Gilbert Hernandez approaching his drawing board these days like Lawrence of Arabia approaching a Turkish convoy: “NO PRISONERS! NO PRISONERS!” In a year suffused with comics funneling pitch-black darkness through a combination of sex and horror, none were blacker, sexier, or more horrific than this gender-bending exploitation flick from Beto’s “Fritz-verse.” None also functioned as a rejection of the work that made its creator famous like this one did, either. Not a crowd-pleaser like his brother, but every bit as brilliant, every bit as fearless.

3. Garden (Yuichi Yokoyama, PictureBox): Like a theme park ride in comics form — with the strange events it chronicles themselves resembling a theme park ride — Yokoyama’s book is a breathtaking, breathless experience. Alongside his anonymous but extravagantly costumed non-characters, we simply go along for the ride, exploring Yokoyama’s prodigious, mysterious imagination as he concocts a seemingly endless stream of increasingly strange interfaces between man and machine, nature and artifice. As a metaphor for our increasingly out-of-control modern life it’s tough to top. As pure thrilling kinetic cartooning it’s equally tough to top.

2. Big Questions (Anders Nilsen, Drawn & Quarterly): Last year, I wrote that if the collected edition of Nilsen’s long-running parable of philosophically minded birds and the plane crash that turns their lives upside-down didn’t top my list whenever it came out, it must have been some kind of miracle year. Turns out that it was. But you’d pretty much have to create a flawless capstone to a thirty-year storyline of neer-peerless intelligence and artistry to top this colossal achievement. Nilsen’s painstaking, pointillist cartooning and ruthless examination of just how little regard the workings of the world have for any given life, human or otherwise, marks him as the best comics artist of his generation, and solidifies Big Questions‘ claim as the finest “funny animal” comic since Maus.

1. Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 (Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez, Fantagraphics): Gilbert got his due elsewhere on my list, so let’s ignore his contribution to this issue, which advance the saga of his bosomy, frequently abused protagonist Fritz Martinez both on and off the sleazy silver screen. Instead, let’s add to the chorus praising Jaime’s “The Love Bunglers” as one of the greatest comics of all time, the point toward which one of the greatest comics series of all time has been hurtling for thirty years. In a single two-page spread Jaime nearly crushes both his lovable, walking-disaster main characters Maggie and Ray with the accumulated weight of all their decades of life, before emerging from beneath it like Spider-Man pushing up from out of that Ditko machinery. You can count the number of cartoonists able to wed style to substance, form to function, this seamlessly on one hand with fingers to spare. A masterpiece.

Comics Time: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century: 1969

September 14, 2011The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969

Alan Moore, writer

Kevin O’Neill, artist

Top Shelf, August 2011

80 pages

$9.95

Buy it from Top Shelf

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

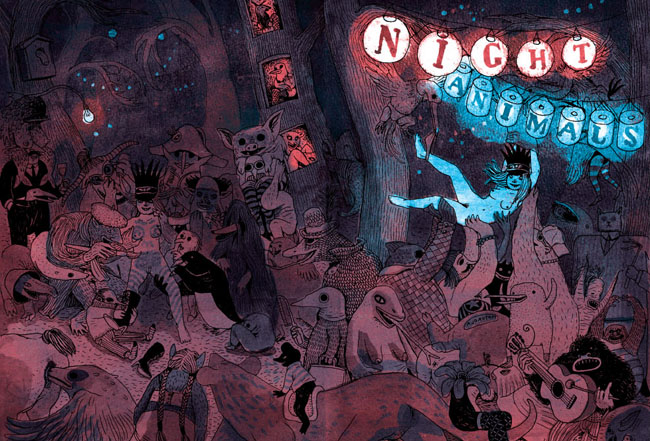

Comics Time: Night Animals

June 24, 2011Night Animals

Brecht Evens, writer/artist

Top Shelf, January 2011

48 pages

$7.95

Read a preview and buy it from Top Shelf

Dare I say that this is even better than The Wrong Place? I think I dare! Created before that book but published in English after it, Night Animals is a more traditionally drawn affair from author Brecht Evens in that it is, in fact, drawn. The Wrong Place‘s paint-only art was its distinctive selling point and, via clever coloring, its primary storytelling mechanism, but as it turns out this innovation meant Evens abandoned a really lovely line — thick, ropy, tactile, full of motion, fun. It gives the art more immediate pop, and gives Evens’s really vibrant colors (look at that cover; now imagine a whole book like that) the day off, as it were, freeing them from the burden of telling the story themselves and allowing them to comment on and enhance the action, and of course simply delight the eye.

Said action consists of two separate stories in which the protagonists’ sexuality is passed through a gauntlet of children’s-story-style creatures of the wild. The first, in which a balding businessman and apparent tyro furry goes down a literal rabbit hole and braves an increasingly terrifying series of beasts on his way to the “Blind Date” that gives the story its title, has a happy ending: A grinning, recumbent woman in rabbit ears, probably a little plain under normal circumstances with her hornrimmed glasses and mole and pointy schnoz but bomb-ass hot as she’s presented at the end of this journey, with a promising white arrow directing her bunny-suited suitor straight to her crotch. After the painstakingly delineated labyrinth we’ve followed to get here, including a pair of stunning spreads filled with seemingly every sea monster and forest creature Evens could think of, this punchline image elicited a good-natured “haw!” from me; if I’d been there, I’d have high-fived both the guy and the girl before leaving them to get it on. Indeed, the very last image, a Wrong Place-style painted silhouette of the two characters in floppy-eared flagrante delicto, gives the impression of the artist quietly backing away and closing the door behind himself, letting our hero and heroine do their stuff in peace. Evens really nails the simple satisfaction sex sometimes provides — life can be filled with storm and stress, but every now and then it’s nothing that a special someone’s smile and genitals can’t fix.

The scarred side of the Night Animals coin is the second and concluding story, “Bad Friends.” (“So it’s not just a clever name.”—Wayne’s World) It starts, and indeed continues, innocuously enough, as a sort of distaff Where the Wild Things Are/Aesopian cover version of Stephen King’s Carrie, in which puberty rather than petulance is what enables our young protagonist to heed the call of the wild, and in which the rapid locker-room onset of menstruation leads not to a telekinetic killing spree but a visit from the Great God Pan, a trip on the back of a giant bird, and a rockin’ party with various critters in the woods. Our heroine whoops it up, enjoying the nakedness her newfound friends have reduced her to — complete with body-paint heart drawn around her pudenda — so much so that she doesn’t notice the darkness in their eyes as they close in to devour her. This story ends not with a clinch, but an empty bloodstained bed, worried parents, an ineffectual search of the now-empty forest, a single flower wilting on the ground. Evens’s trademark red goes from a spot-color stain on the girl’s underwear, to the alluring light of an illicit night out, to a symbol of sexual abandon, to the color of violence and death. It’s quite a performance, sexy and creepy at precisely the moments Evens wishes it to be one or the other, and a direct contrast with the earthy lightheartedness of the opening story. It’s awfully easy for sex comics to get didactic in their rah-rah positivity; Evens gives us the flipside, counting on us to be grown up enough to weigh the pros and cons ourselves. Good for him and good for this comic. It’s a blast.

Comics Time: AX: Alternative Manga Vol. 1

January 26, 2011 AX: Alternative Manga Vol. 1

AX: Alternative Manga Vol. 1

Osamu Kanno, Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Imiri Sakabashira, Takao Kawasaki, Ayuko Akiyama, Shigehiro Okada, Katsuo Kawai, Nishioka Brosis, Takato Yamamoto, Toranosuke Shimada, Yuka Goto, Mimiyo Tomozawa, Takashi Nemoto, Yusaku Hankuma, Namie Fujieda, Mitsuhiko Yoshida, Kotobuki Shirigari, Shinbo Minami, Shinya Komatsu, Einosuke, Yuichi Kiriyama, Saito Yunosuke, Akino Kondo, Tomohiro Koizumi, Shin’ichi Abe, Seiko Erisawa, Shigeyuki Fukumitsu, Kataoka Toyo, Hideyasu Moto, Keizo Miyanishi, Hiroji Tani, Otoya Mitsuhashi, Kazuichi Hanawa, writers/artists

Sean Michael Wilson, editor

Mitsuhiro Asakawa, compiler

Top Shelf, 2010

400 pages

$29.95

Buy it from Top Shelf

Buy it from Amazon.com

This is a tough one. I mean, as a Whitman’s Sampler of approaches to Japanese comics outside of the Japanese mainstream, this inaugural English-language compilation of comics from the fat, regularly released alternative-manga anthology series AX strikes me as wide-ranging and comprehensive, almost to a fault. In terms of known quantities for American altcomix readers, you’ll find both the straightforwardly drawn irony of gekiga pioneer and a A Drifting Life author Yoshihiro Tatsumi and the over-the-top visual and thematic crudeness of Monster Men Bureiko Lullaby‘s Takashi Nemoto represented here. You’ll see comics that look very much like the lavishly illustrated horror or porn manga you might have come across (Takato Yamamoto, Keizi Miyanishi, Kazuichi Hanawa) and comics that are so far removed from the manga tradition and so similar in bold graphic spirit to the first wave of North American alternative comics that they’d fit in RAW (Nishioka Brosis, Otoya Mitsuhashi). In perhaps the most marked deviation from work from the equivalent time period (turn of the millennium) here in North America, there’s a metric ton of crass taboo-shattering of the sort cartoonists here haven’t been all that interested in as an end in itself since the underground days (Tatsumi, Nemoto, Mitsuhashi, Osamu Kanno, Shigehiro Okada, Kotobuki Shiriagari, Saito Yunasuke, Hiroji Tani), but there are also twee little slice-of-lifers, modern urban fables, and O. Henry/New Yorker litfic that you could easily see populating a Petit Livre from Drawn & Quarterly or an issue of Mome (Takao Kawasaki, Katsuo Kawai, Shinbo Minami, Akino Kando, Shin’ichi Abe, Shigeyuki Fukumitsu).

So your preferred color of the alt/art/lit/indie/indy/underground spectrum is almost surely represented somewhere in these pages, and chances are you’ll find something you’ll consider a minor revelation. In my case, I was really impressed by the murky, inky body-horror dream comic “Conch in the Sky” by Imiri Sakabashira, the title of which gives a pretty solid impression of what you can expect. Brosis’s “A Broken Soul” combined off-kilter 2-D character designs, a wiry thin line, gray textures that looked like an artifact of photcopying, and a sort of whimsical ennui, to remind me favorably of Mark Beyer. And Shinya Komatsu’s “Mushroom Garden” is a real stunner, its bulbous, plush mushrooms evoking an array of psychedelic comics practitioners from Vaughn Bode to Moebius to Brandon Graham. In other words I don’t regret the time spent with the volume at all, and it’s given me several promising roads for further exploration, god and translators willing.

That said, AX Vol. 1 is consistently undercut not just by the heavy hand of many of its contributors, too many of whom rely on shock value or Tatsumiesque hamfisted irony, but by various production shortfalls. First and foremost among those is the translation work by Spencer Fanctutt and Atsuko Saisho, which is the epitome of the translated-manga tendency to emphasize fidelity at the expense of clarity. Here’s a representative passage from Shigehiro Okada’s sex farce “Me”: “However strangely I might dress, if I could really slip my existence, I could become a part of the cityscape like those ruins of decades ago. My instinct would explode if it took form. The light holds death. The darkness holds life. That’s what I’m waiting for. I…I would die for its expression.” If it’s not a sentence you can imagine a native English speaker coming up with, you’ve got to go back to the drawing board!

Meanwhile, while the design and font selection for the jacket, table of contents, and ancillary material (including Paul Gravett’s informative, if slightly overwritten, introduction) are all quite strong, the lettering for the comics themselves is frequently distracting, with inexpressive computer fonts and, often, vast empty spaces in balloons and caption boxes where kanji clearly used to reside. Finally, the decision to list creators first-name-first in the TOC and on each page but last-name-first in the who’s-who at the back of the book is a baffling one.

None of these things are dealbreakers in and of themselves. Heck, I don’t think they’re dealbreakers even when all added up. Like I said, there are a lot of intriguing comics in here, and a few excellent ones, and the cumulative effect is an eye-opening and educational one if you’re a reader with an interest in Japan’s equivalents to the American alternative comics you enjoy but few inroads into them. But in a field that’s increasingly crowded with impeccably conceived, assembled, edited, and packaged anthologies, AX isn’t just competing with scanlators and sporadic English-language apperances in long out-of-print publications, it’s competing with what the Eric Reynoldes and Zack Sotos and Sammy Harkhams and Ivan Brunettis and Ryan Sandses and so-ons of the world are putting together. It’s in that sense that AX could stand to be sharpened. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Comic of the Year of the Day: The Troll King

December 8, 2010Every day throughout the month of December, Attentiondeficitdisorderly will spotlight one of the best comics of 2010. Today’s comic is The Troll King by Kolbeinn Karlsson, published by Top Shelf — a suite of earthy fairy tales with equal parts heart and groin.

Like the work of some kind of less violent altcomix Clive Barker, Kolbeinn Karlsson’s The Troll King is a defiant, love-it-or-shove it celebration of monstrousness, queerness, and the dreamlike Venn diagram overlap between the two. The burly beasts who inhabit the forest just beyond the glow of the city lights in this suite of interconnected stories have, through “hard work” and because society is “not worthy of [their] presence,” created a world for themselves, a world of their own, a world where their “bodies” and their “pleasure” are their “first priorities.” In this place, the creatures are stocky, broadly designed, miraculously self-perpetuating species, evoked with a wavy, almost furry line and bright, flat colors for an overall effect that wouldn’t look out of place in a Kramers Ergot tribute to Super Mario Bros. 2.

Click here for a full review and purchasing information.