Posts Tagged ‘tilghman’

008. “$5,000 up front. $500 a night. Cash. You pay all medical expenses.”

January 8, 2019According to 2017 research by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median pay for a security guard or gaming surveillance officer, the closest career to bouncer or cooler that the BLS tracks, was $26,900 a year. Assuming Sundays off and not counting the stipulated coverage of all medical expenses, a conservative estimate of the yearly salary paid to Dalton by Frank Tilghman for his services as a cooler at the Double Deuce comes to $328,259.17 in 2019 dollars.

Tilghman prefaces his offer of employment to Dalton by saying “I’ve come into a little bit of money [and] I’d like to make a better life for myself.” Based on the elaborate redesign for the Double Deuce unveiled later in the film, he’s not kidding about the money. But the redesign, which we see him penciling on drafting paper the night Dalton shows up in Jasper, is meaningless if the volume of patrons required to make a bar that large and expensive a worthwhile investment doesn’t materialize. As Dalton himself puts it, “People who really wanna have a good time won’t come to a slaughterhouse.”

Dalton is the man who puts a stop to the slaughter. Though neither man knows it will happen when they make their deal, Dalton also breaks the back of the local organized-crime outfit, which according to Red Webster takes a minimum of “ten percent—to start” of gross income from every business in town. In fact, by personally murdering five of the town’s most violent criminals, beating a dozen or so others badly enough that they will never return, and driving one more to a Damascene conversion by dropping a stuffed polar bear onto him in a rich lunatic’s basement, Dalton eliminates the town’s bad element altogether.

Three-twenty-eight large is a bargain.

003. The Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri

January 3, 2019If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig. —Uilliam M. Bricken, Jr.

An English professor of mine used that self-reflexive riddle to illustrate the way Christ’s parables are both medium and message: The second the concept behind the parable clicks, so does the larger point about ethical behavior or spiritual enlightenment.

In his book The Three Christs of Ypsilatnti, psychologist Mark Rokeach recounts an experiment, which he would later apologize for and reject as unethical, in which he placed three men who believed themselves to be Jesus Christ in regular group therapy sessions in hopes that encountering each other would shatter their delusions, to which end he occasionally manipulated them directly by concocting imaginary elements of their collective story himself. The experiment was unsuccessful.

This man is Big “T” of Big “T” Auto Sales, or so it seems safe to assume. We meet him around 17 minutes into the film, as he watches The Patty Duke Show on his office television while preparing to eat his lunch. He then notices our hero, Dalton, checking under the hood of a beat-up old car in the lot. “She’s a runner!” shouts this walrus-looking sonofagun as he strides out to meet Dalton face to face, treating the singular requirement of any used car sale—that the car being sold is capable of movement—like a selling point. Dalton drives a Mercedes when he’s not on the job, but since angry patrons of the bars at which he serves as cooler tend to take their frustrations out on his car after they’re ejected, he replaces it with a cheaply bought beater when he’s got a gig. He takes the car. We never see Big “T” again.

This man does not have a name, not that we’re given to know anyway. We meet him about one minute after we meet Big “T.” This fellow presides over some kind of automobile junkyard Dalton goes to not to purchase a used car, which he could have done here since used cars are visibly on sale in the background, but to stock up on spare tires, since people who are pissed off that he smashed their face through a table because their girlfriend was dancing on another table often slash his tires in revenge. Dalton loads the trunk of his new old car with tires and gives the proprietor a little salute, which the old man returns. We never see this man again.

This man is Red Webster, proprietor of Red’s Auto Parts. We meet him around 33 minutes into the film, after which he becomes a major character. His store is the closest business to the Double Deuce, with which it shares some kind of vast dirt parking lot or road or whatever it is despite being about a football field away. His niece is Dr. Elizabeth Clay, former love interest of Brad Wesley and, soon, current love interest of Dalton. He is Dalton’s primary source of information on the protection racket run by Brad Wesley under the guise of civic improvement. Dalton goes to Red’s store to order a new windshield and buy a new antenna for his car after both were destroyed by angry ex-patrons of the Double Deuce the night before. This is the third scene in which Dalton makes an automobile-related purchase, and the third business establishment at which he does so. The movie is not quite 35 minutes old.

This man is Pete Strodenmire, proprietor of Strodenmire Ford. We meet him around one hour and 24 minutes into the film, at a hastily convened meeting of Jasper business owners, plus Dalton and Elizabeth, to discuss the prior night’s destruction of Red’s Auto Parts in an arson ordered by Brad Wesley. There are seven people at this meeting. Four are Dalton, Elizabeth, Dalton’s nominal boss Tilghman (seen above in the background), and Elizabeth’s uncle Red. The other three, including Strodenmire, are people we’ve never seen before; the two who aren’t Strodenmire have no lines, and we never see them again. The next time we see Strodenmire, Brad Wesley has ordered one of his goons to run over the man’s entire glass-enclosed showroom of new cars with a monster truck, which he does with glee. Strodenmire winds up being one of four men—along with Red, Tilghman, and Dalton’s nominal landlord Emmet—who murder Brad Wesley, the film’s antagonist, with shotguns during the climax. Again, we meet him an hour and a half into a two-hour film that has already included three other car or car-parts salesmen.

This man is Emmet. We meet him about half a minute after we meet the man from whom Dalton purchases tires, when he rents Dalton a barn-loft apartment that must have cost $50,000 dollars to build for $100 a month. He doesn’t sell cars or car parts, but you can see how he and the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri share a similar aesthetic.

Road House is a movie about a road house, that much is true. It’s not a movie about roads, however, nor about what you drive on them. (Much more time is spent showing Dalton buying cars, parking cars, and buying car parts to fix what happens to the cars after they’re parked, than is spent showing anyone actually driving cars.) Thus, the film’s maximalist approach to automotive retailers is striking, and bears contemplation.

Could Dalton’s trips to fully four different stores for his vehicular needs have been consolidated to, say, two, perhaps the ones owned by the two men who wind up saving his life from the character played by Ben Gazzara (John Cassavetes’s Husbands)? Yes.

Would this have been an easy way to establish Strodenmire, who I stress fires a shotgun into the body of the movie’s antagonist and inflicts a mortal wound, before the movie was three quarters of the way finished? Yes.

Would this have made things less confusing to people for whom men whose vibe is best described as “Old Fart” sort of blend together in an indistinguishable blur of ill-fitting work shirts and bold facial-hair decisions? Yes.

Is understanding that Road House has its protagonist make car-related purchases from three different men (two of whom are never seen again), includes a fourth as a main character when he emerges from a nameless scrum of unknowns when the movie is almost over (and who has never been seen before), and casts weird old coots in all four roles (with weird old coots to spare playing other parts)—that is to say, understanding things that makes no sense—key to understanding Road House‘s unique rhythm in all its concussive dreaminess?

If this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.

001. Fame

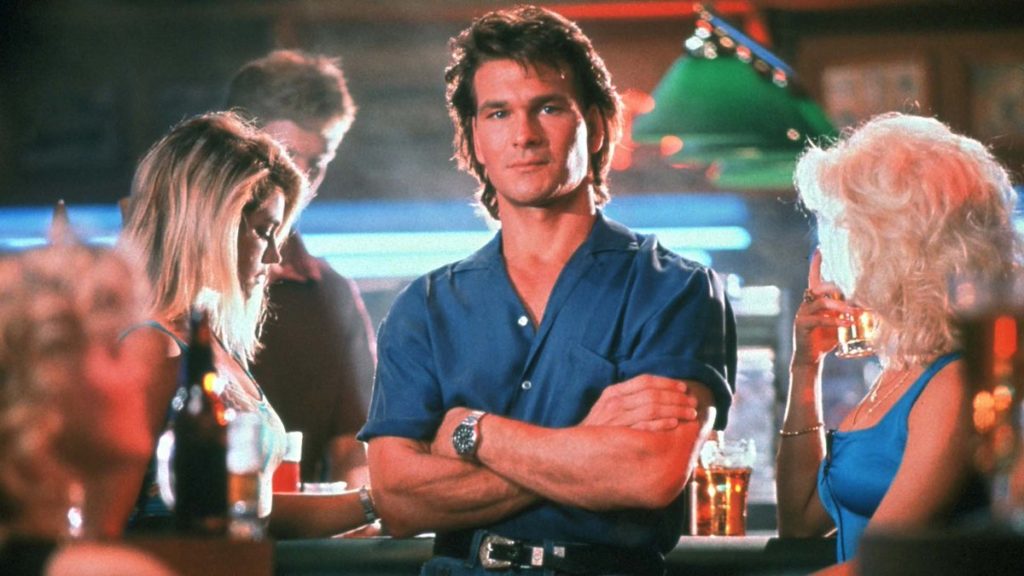

January 1, 2019 Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

So that tells you something about the kind of film Road House is: It respects the people who beat up people who beat up other people in bars so much that it affords them significant renown. Other men will fly across the country and offer these men hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for their services. Barfolk, for want of a better term, whisper their names in reverent awe. In the land of the blockheaded, the two-fisted man is king.

Because their reputations precede them, or because to invoke them inaugurates the ritually contracted cycle of redemptive violence for which they’ve been hired, the bouncers of Road House are reluctant to share their names.

“You got a name?” asks Carrie Ann, waitress at the Double Deuce, the ultraviolent Missouri honky-tonk at the heart of the story. “Yeah,” answers our hero.

“What’s your name, buddy?” asks Pat, the Double Deuce’s thieving failnephew bartender, who is played by John Doe of Los Angles punk institution X. “Coffee, black,” responds our hero.

When he conducts his first official bouncing during his tenure at the Double Deuce by smashing the face of a man with a switchblade and a Hawaiian shirt through a table adjacent to the one on which this man’s girlfriend has been dancing and thus lowering the overall atmosphere of class in the establishment, it falls to our hero’s blind white blues-playing guitarist friend Jeff Healey (appearing as himself) to reveal his identity to the amazed, and in several cases visibly aroused, patrons.

“The name,” he says, “is Dalton.”

Dalton is by this point in the film known to the Double Deuce’s staff, over whom he’s been given absolute authority by the bar’s bizarre owner Frank Tilghman. “What he says? Goes,” Tilghman tells his employees.

“It’s my way or the highway,” Dalton concurs.

The first person to learn his identity other than Tilghman himself is Carrie Ann, who powers through our hero’s extremely badass rebuff as described above and gets him to name himself, the way Superman tricks his gnomish extradimensional enemy Mr. Mxyzptlk into saying his own name backwards to eliminate him. (Carrie Ann has no such goal, of course; it is perhaps for this reason that she is rewarded later in the film with a glimpse of our hero in the nude. to which she reacts with slackjawed lust so powerful, courtesy of actor Kathleen Wilhoite, that it all but glows with its own internal erotic energy.)

“Shit,” Carrie Ann says when Dalton reveals himself. “I heard a’ you!”

The news spreads like wildfire through the waitstaff, bartenders, and bouncers already in the Double Deuce’s employ, none of whom need its import explained to them. Like I said, a famous bouncer’s reputation precedes him. One man has heard he ripped a guy’s throat out with his bare hands. Another has heard he has balls big enough to come in a dump truck. “Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name,” runs the song from another artifact of Eighties bar culture. Dalton can go anywhere.

Which gives us some indication of his exact level of fame. No one at the Double Deuce recognizes him on sight, which means he’s not so famous that his face alone writes his ticket for him. However, the moment he says “Dalton” in response to Carrie Ann’s query, she immediately assumes he is the Dalton famous for being a bouncer, and not any of the other myriad possible Daltons in the world—B. the bookseller, for example. It’s as if she asked a woman who was new to the Double Deuce for her name, and that woman replied “Gaga.” Only one person leaps to mind.

This separates our hero from his hero. “Wade Garrett’s the best,” Dalton tells Tilghman when the Missouri restaurateur says he’s heard he, Dalton, is the best. “Wade Garrett’s getting old,” Tilghman replies. But age has not dimmed his starpower. Arguably, age is responsible for it. The longer he’s been out there, bouncing and cooling, the more time the dive-bar demimonde has had to put a face to the name.

The face belongs to Sam Elliott, who in this film has long greasy hair, tight black jeans, five o’clock shadow that creeps up his face nearly to his eyes, and a grizzled sexuality that wafts from the screen like a musk. When he arrives at the Double Deuce to help his one-time protégé Dalton defend the establishment against the depredations of Brad Wesley, a local business tycoon and J.C. Penney franchisee played by Ben Gazzara (The Killing of a Chinese Bookie), no one asks his name, because no one needs to. Practically the entire staff stares at him with the wide eyes of children in a film directed by Chris Columbus when he limps bowleggedly into the place looking for his mijo.

Grinning slyly, his eyes twinkling with a sinister delight that seems to be actor Kevin Tighe’s natural mien and has no basis within the character itself, Tilghman looks at this man and says, “I know you.”

Wade Garrett, it can be concluded, has achieved a level of fame so total that even people steeped enough in bouncer culture to know Dalton by name know him by sight. Michael Jordan fame. Michael Jackson fame. Santa Claus fame. Wade Garrett is the best, Dalton tells us. And when Dalton speaks, we would do well listen. It’s his way or the highway. What he says? Goes.

Directed by Rowdy Herrington, written by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin (Academy Award winner, Wag the Dog), released in 1989, directed by Rowdy Herrington (the name bears repeating), and starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara, and an assortment of people with anywhere between one to six lines of dialogue all of whom I adore completely, Road House is one of my favorite movies ever made. I like to talk about it. I hope you’ll like to listen.