Posts Tagged ‘the double deuce’

040. The Second Rule

February 9, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This is the second.

2. Take it outside. Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary.

A bouncer less wise than Dalton would think Rule 2 begins and ends right here. How much more could there possibly be to this purely practical commandment? Your job is to maintain a convivial atmosphere for the patrons of your establishment by keeping the bad element at bay. You can’t do this if you’re beating the shit out of a guy on the dance floor. Ergo, you either force or lure your opponent out of the bar—your ultimate goal at any rate—before engaging in fisticuffs. What else is there?

What else indeed. As you can no doubt imagine, many, many violent incidents occur at the Double Deuce between this speech and the end of the movie. Dalton and his men take it outside a grand total of once during that time. Dalton in fact grabs a guy by the back of the head and smashes his face through a table this very night. What conclusion can we draw from this?

What we have here is another “If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig” situation.

Let’s start with the assumption that Dalton, as evidenced by his own actions, must intend this rule to have some larger meaning beyond its (eminently sensible) practical application regarding the bouncer’s ideal field of battle. I would suggest that we look to the Third Rule for the key to unlock this mystery. A thorough examination of that rule must wait for another day, but for now suffice it to say “It’s nothing personal” is a central component.

Could it be the case that in commanding the staff of the Double Deuce to “take it outside” when the moment of truth arrives, what Dalton really means is to step outside themselves? Those who follow the Dalton Path must see themselves as parts of a greater whole. They are but tools in the hands of the Cooler; does the hammer hate the nail? They are the immune system of the bar-organism; does the white blood cell hate the infection in the wound? The bouncer is the agent of Gemeinschaft. Proper function necessitates depersonalization so that the wider view may come into focus.

Now let us go further. What is it to “start something inside the bar”? We have already learned that many of the forces that threaten the Double Deuce are not conflicts that arise organically between patrons, but deliberate infiltration and provocation directed by an outside agent: Brad Wesley. Wesley himself is merely a symptom of larger societal crises: capitalism generally, the tyranny of the small business owner specifically, toxic masculinity, and even, as we will see when we enter his Trophy Room, ecological destruction.

Moreover, let us not allow “conflicts that arise organically between patrons” to pass by unremarked upon. Dalton identifies the Double Deuce’s problematic clientele as “Forty-year-old adolescents, felons, power drinkers, and trustees of modern chemistry.” Cultural neoteny, the carceral state, alcoholism and addiction, and the role of business and government in fomenting all of the above: One need not absolve the meathead or the Knife Nerd of personal responsibility to correctly argue that they themselves are often victims of forces far beyond their control.

Now let us return to the Second Rule. “Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary,” says the man who will break a piece of the bar’s furniture in half with another human being’s face just a few short hours later. Who is he really addressing here, and what is he saying to them? Is he simply telling the bouncers (and waitstaff and bartenders and band members and the unknown entity in the brown jacket) to avoid throwing hands inside these four walls? Or is he employing paradox to demonstrate that nothing ever truly starts inside the bar—that while the Dalton Path offers a safe route through the bar for all who choose to walk it, it is a road without beginning or end?

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms. (Ephesians 6:12)

039. Biker Gang

February 8, 2019The very first people to give Dalton shit upon his arrival in Jasper aren’t Brad Wesley and his goons. They aren’t the corrupt members of the Double Deuce’s staff. They aren’t even Knife Nerds or other random ne’er-do-wells among the club’s clientele. They’re a biker gang, in the Double Deuce’s parking lot. “Mer-SAY-dees!” they whoop it up as Dalton parks his luxury work of German engineering in the unpaved unloading zone for the town’s worst element, glaring at him all the while. “Hey hotshot! What’s wrong with Dee-troit cars?” Dalton simply stares back at them and their bikes and their very cool ’80s bad-guy car, tosses away his cigarette, and goes about his business. You and I are left with more to ponder.

At first blush it’s just a bit of color, a way to convey that the Double Deuce is a rough and tumble environment before you so much as step through the doors, in the same way that watching Morgan the evil bouncer toss a guy through those doors a few seconds later (“Don’t come back, peckerhead!”) lets you know what you’re in for once you set foot inside. What makes it a uniquely Road House bit of color how none of it has the slightest relevance at any point in the future, and how no element of it is ever heard from again.

Are biker gangs a threat Dalton will face in his quest to clean up the Double Deuce, and eventually the entire town of Jasper? No. Not even a little bit, in fact. The problems all stem from Brad Wesley, the Fotomat King, and his merry band of assholes. This is Road House, not The Road Warrior. Though Dalton and Brad Wesley could well be the Mad Max and Lord Humungus of the post-guzzoline Missouri wastelands should it come to that, this is merely informed speculation.

Is there a slobs vs. snobs angle to the movie? Again, no. For one thing Dalton always stows away his fancy car and uses a ringer instead once he starts working, so he doesn’t even bring the Mercedes back to the Double Deuce, or anywhere else for that matter, until the end of the film. He doesn’t ostentatiously spend his money, or wow the local yokels with his citified ways, or even crow about his NYU philosophy degree to woo Dr. Elizabeth Clay. What’s wrong with Dee-troit cars? Nothing, as far as he’s concerned. (This is a question better directed at Brad Wesley.)

Maybe these guys play a role in the ensuing all-hands-on-deck barfight, the movie’s first? Once again, no. The instigators and all the primary combatants are just the usual drunken shitbirds and meatheads. While it is true that one of the bikers miraculously appears inside as the Shirtless Man about twenty seconds later, this is down to Road House‘s charmingly free-form approach to continuity, rather than the idea that this guy somehow raced around to a back entrance, bared his chest, and started boogying down in the time it took Dalton to cross the parking lot and enter from the front. The Shirtless Man, at any rate, is a dancer, not a fighter.

But in their own pointless way, the bikers illustrate the importance of Dalton’s First Rule: “Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected.” Your enemies could look like anyone, come from anywhere, and attack at any time, even if their offense consists solely of “Buy American” jingoism. A cooler of Dalton’s experience and skill would have devised a plan for combatting these creeps within seconds, and likely kept it filed away throughout the course of the film, in case Brad Wesley ever hired them to run his clunker off the road, or prevent him from accessing one of Jasper’s many auto and auto-parts dealerships—or, less facetiously, bring the fight to grizzled old road dog Wade Garrett before he so much as parks his motorcycle. Indeed, one could argue that Dalton’s purchase of a beat-up car to replace his Mercedes was his way of defeating these opponents by depriving them of their casus belli. Victory is his before battle is joined.

038. The Laughing Man

February 7, 2019The men who look at Dalton are not the only Road House characters who model behavior for their audience. Nor are the women. To understand this movie, one must understand the Laughing Man.

An anomalously odd, almost Lynchian presence in a film that’s otherwise much more straight-down-the-middle in its abject stupidity, the Laughing Man is an avatar for the audience in that the events of the film transmogrify him from observer to participant.

A member of the rogues gallery that greets Dalton upon his arrival at the Double Deuce, he is at first content to simply watch the opening barfight unfold, giggling and guffawing and going slightly crosseyed like a cartoon woodpecker all the while. As a matter of fact, he is at second content to do so, and at third, and presumably ad infinitum. In an another world, perhaps one in which Wes Bradley successfully wooed the first Dillard’s to Casper, Wyoming, this hyena-man is still standing by the bar, laughing like a Joker henchman at everything that has since unfolded. The fool on the hill sees the goons going down.

But that is not the world we inhabit.

In this world, the ageless waitress who appears to have started working at the Double Deuce after quitting her job at Norma Jennings’s Double R lobs a bottle through the air, intending to hit some other asshole but clocking this harmless nimrod right between the eyes instead. He goes down with the kind of exaggerated overselling you see from pro-wrestling mid-carders, or from anthropomorphic animals around whose heads birds chirp in a saturnine orbit after someone hits them with a rolling pin.

The waitress looks upon her works and despairs. But should we? No! The Laughing Man is concussed so that we might continue. He shows us that no matter how much we might wish to laugh at this movie, it will draw us in until we have no choice but to laugh with it, or suffer for our refusal. You are in the Jasper of the mind now. Laugh and the world laughs with you!

037. Denise & Carrie Ann

February 6, 2019I was a theater kid in high school, and yes, I am glad you were sitting down. As the president of the Drama Club, the only coed activity my all-boys Catholic high school had to offer, I usually had better things to do than nitpick blocking, from learning my own steps to realizing how unforgiving for teenage boys pleated dress pants can be. But I did have one pet peeve I remember to this day.

Pretty much every musical in the high-school repertoire has around three or four major characters who—whether because they’re too old, too young, don’t sing, don’t dance, aren’t residents of the town/actors in the company/members of the Conrad Birdie fanclub, or any number of other factors—don’t take part in the big dance numbers, or aren’t active in the events of a particular show case scene. However, they are often at least present at those times, typically clustered in little groups around the perimeter. What would always bug me was when two characters who’d never spoken to each other before in the show, and for whom because of narrative economy it would be a big deal for them to speak to each other, like worthy of a song and dance of their own, wound up standing next to each other, stage-whispering about Professor Harold Hill’s latest chicanery or whatever.

I think about that when I watch Denise, Brad Wesley’s kept woman, and Carrie Ann, the Double Deuce’s coolest employee, team up during the first big fight. They cower together to shelter from the action. They root and heckle and holler as a unit. They wrap protective arms around one another when the going gets tough. Denise cheers Carrie Ann on when she starts slugging one of the participants. She actually hands her a bottle to use as a weapon!

Do these characters have anything in common? Do they have any mutual friends? Do they ever speak to each other…I was gonna say again, but really the phrase I’m looking for is at all? Do they even come within five feet of one another? If you’ve read thirty-six essays about Road House and counting you’re no doubt familiar enough with the film’s approach to continuity to answer those questions. But there’s a gigantic fight scene going on, and they’ve gotta stand somewhere, and the director is probably too busy telling gigantic men which tables to fall through, so a few perfunctory “stand over there”s are all they got, and they improvised. If it helps, imagine they’re the juniors playing Mayor Shinn and Mrs. Paroo, silently emoting together while forgetting to cheat toward the audience during “Shipoopi.”

034. Thru the Eyes of Tilghman

February 3, 2019It goes ill with the Double Deuce. Frank Tilghman colorfully describes it to Dalton upon their first meeting as “the kind of place where they sweep up the eyeballs after closing,” and other than the lack of actual traumatic globe avulsions nothing we witness when we arrive contradicts this. It’s a hellhole. The bartender is a nepotism hire who robs the joint blind. The band gets pelted with bottles when they take five in order to urinate. The chief bouncer starts fights. Another bouncer fucks teenage girls in the supply closet. A waitress sells coke in the bathroom (presumably interfering with those customers who wish to snort coke in the bathroom, as is custom in classier establishments). Bottles, glassware, and furniture get smashed as regularly and thoroughly as the customers do. The owner is forced to waste precious man-hours bowdlerizing graffiti.

This much we know—now, anyway. But during the opening sequence, prior to our first visit to the Double Deuce, prior even to Tilghman’s description of the place to Dalton, we don’t know any of this unless we have watched the entire film before. That opening sequence, which depicts Frank Tilghman’s journey through the capacity crowd at the massively popular Bandstand where Dalton works at the time, is one of the reasons Road House rewards repeat viewings: Only people who’ve already witnessed the nightmare that is the pre-Dalton Double Deuce can understand what the hell Tilghman is doing.

In short order, Frank Tilghman marvels at…

- a handrail

- a bartender pouring shots

- a cash register ringing up a sale

- a waitress carrying a tray of drinks

- a man lighting a cigarette for an attractively dressed woman

- a credit-card transaction

- a man leaving a large cash tip

- a bar band

Remember, and this is key: Frank Tilghman owns a bar.

If you think I’m kidding about Tilghman “marveling at” these things, watch actor Kevin Tighe’s eyeline as he looks at each of these things in turn, whether within frame or via match cuts to the actions and objects in question. Then look at his face afterwards. He’s impressed. Thoroughly so. He takes it all in so intently that he reads like a villain casing the joint. Granted, he reads like that all the time, but as we’ve established, nothing that happens during the opening happens by accident.

You wanna know how bad things have gotten at the Double Deuce? Frank Tilghman, who owns a bar, looks at the basic components of literally any bar on earth like the apes look at the monolith in 2001. Forget the eyeballs on the floor. Just follow the eyeballs in Tilghman’s head.

033. Dead man

February 2, 2019When Dalton fires Morgan, the irascible bouncer played by pro wrestling legend Terry Funk, from the Double Deuce because he doesn’t have “the right temperament for the trade,” Morgan reacts as if determined to prove this was the right decision. “You asshole,” he growls. “What am I supposed to do?” “There’s always barber college,” Dalton deadpans in reply. The rest of the staff laugh at Morgan then, openly and for what I’d imagine is the first time. Dalton has defanged him.

Pointing his finger in Dalton’s face, Morgan delivers his farewell prediction: “You’re a dead man.” He nearly smacks his severance check out of Tilghman’s hand as he grabs it, then storms away.

Road House fans—Roadies—enjoy this interaction a great deal. It’s at least partially obvious why: How often do you get to see Patrick Swayze (Dirty Dancing) and Terry Funk (Halloween Havoc ‘89) tread the boards together? But it’s Funk’s innovative line readings that make this a standout scene.

He previews the direction he’s headed when he calls Dalton an asshole, which he pronounces “asshole,” emphasis very much on the second syllable and, one assumes, that particular aspect of the anatomy. Two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response, right? For Morgan—and he’s not the only person in the film to pronounce the word in this way—”hole” is the lead noun, not “ass.” In his eyes, Dalton is less the cheeks than the evacuating void between.

Still, this might have escaped notice were it not for the coup de grace: not “You’re a dead man,” as every other person in the history of the English language has pronounced it, but “You’re a dead man.” Here, the rationale is a bit harder to parse. Surely no matter what spin you put on this, dead is the most important, and insulting, aspect of the phrase, right? Dalton already knows he’s a man. Dead is the newsworthy part. And in making himself the bearer of this bad news, Morgan is issuing a threat. (This is all obvious, I know, but we’re being methodical.)

So why emphasize “man”? Not to praise Dalton, that’s for sure, despite the rubric established by asshole. He’s putting man front and center in the Shakespearean, “What a piece of work is” way. If we think of Dalton as a man, a human, we imagine all that entails: his infancy, childhood, adolescence, young adulthood; his need to breathe, eat, drink, sleep, excrete; his social and biological drives to form community and find a mate; his hopes and fears and lusts; his prodigious skill and significant renown as a bouncer-philosopher; his future in all its possibility and inevitability. One pissed-off ex-coworker later and this could all be gone, a man reduced to meat and thence to nothing at all. In his own dimwitted way, from a brain that processes only rage and schadenfreude, Morgan is driving home what Dalton stands to lose, and what he plans to take away.

029. Knife Nerds

January 29, 2019A person watching Road House from a remove of decades could be forgiven for wondering if packs of pointy-faced dorks with switchblades, roaming the land and stabbing bouncers, were the subject of some sort of ginned-up panic along the lines of Satanic nursery schools and wilding superpredators. No fewer than four blade-wielding wieners try to slice up Dalton before the film is even halfway over. Though as a category they are a distant second to brawlers in terms of goon prominence, they bear examination for what their presence tells us about Dalton’s world.

These two nitwits are the first people in the film to get bounced, from the Bandstand, before Tilghman hires Dalton away from the place to come work at the Double Deuce. The fellow on the right sparks a bounceable incident when he attempts to pay for the attentions of a young woman who finds the offer insulting and pins the hundred-dollar bill he offers her to the table with a knife; he knocks over her chair by planting a kick right between her legs and we’re off to the races. Dalton thinks he and his men have cooled things off, but this weaselly goof yanks the knife right back out of the table and takes a slice out of the cooler’s arm the moment his back is turned. He and his friend Farrah Fawcett are taken outside by Dalton and company, thinking they’re about to throw down with the man himself. (“I’ve always wanted to try you,” says the knife nerd to Dalton prior to exiting the premises. “I think I can take you.” This is another essay entirely.) But their date with immortality is cancelled when Dalton just turns around and goes back inside. They hurl invective at him in an effort to rile his temper or shame him into combat, but not even such vicious insults as “dirtball” and “moose-lips,” which are things these two people yell at the top of their lungs at a man they’re trying to intimidate, can change Dalton’s mind. Later, Dalton will caution the staff of the Double Deuce against taking such insults personally, since they’re just “two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response.” That knowledge is clearly hard-earned.

This beady-eyed Parrothead is the first person Dalton bounces from the Double Deuce, earning him the undying awe of the people there assembled. All he wants to do is watch his girlfriend dance on a table. Such a fan of her gyrations is he that he attempts to murder, with a knife, the bouncer who asks them to cut it out. “Motherfucker” is his preferred binominal, but what he lacks in creativity he makes up for in extremely loud shirts. Dalton breaks a table with his face, and thus the cooler’s head prevails.

Here’s our old friend Pat McGurn, Brad Wesley’s only sister’s son and the Double Deuce’s now-ex bartender. He’s returned with his fellow goons Tinker and O’Connor in tow to muscle Tilghman into rehiring him, lest Wesley shut down liquor distribution to the bar. When Dalton takes mild, even bemused issue with the idea, Pat whips out a monstrosity that looks like something Legolas would pull out of an Uruk-Hai before lobbing it into another one’s forehead. As he attempts to stab Dalton in the fucking face in front of multiple witnesses in a crowded bar that can be observed clearly through the glass window of the office in which the murder attempt is taking place, he calls Dalton “chicken-dick.” In the end it works out no better for him than it did for Store Brand Crockett and White Tubbs or Hawaiian Punch, but I’m pleased to note that he at least came up with the film’s most ridiculous insult.

For the purposes of this essay I almost didn’t count Ketchum, the unnamed and fundamentally anonymous Brad Wesleyan who drives the monster truck and for whom bladed weapons are a specialty, as we will later learn to tragic effect. Though he is an obnoxious prig, he actually seems like someone you’d think twice about getting in a fight with. That ought to—ought to—elevate him out of Knife Nerd territory. On the other hand, his first knife attack involves attempting to high-kick Dalton in the head with a blade embedded in the toe of his cowboy boot, one of the lamest attempted murders in the movie, and it’s not like the competition isn’t stiff. Dalton catches his leg in midair, twists it savagely, and drags the guy out of the bar on his ass, which he proceeds to kick. Ketchum may look tough. He may even be tough. He doesn’t call Dalton “shit-ass” or “poodle-sack” or anything. But watch him dragged out to the curb like so much stonewashed garbage and then deny the Knife Nerd within at your peril.

All of these men use the blade as surrogate bravery. They may talk a good game—alright, they may talk a game. But when push comes to shove, they attempt to stab. They can whip out whatever they want in their attempt to try and take Dalton. But Dalton’s blade is his body, honed to a nicety, and it will wind up inflicting a far more serious gash than any knife before the story is through. A true cooler is worth a hundred such cowards.

025. Tableau

January 25, 2019Though Dalton gets stabbed within the first few minutes of Road House, it would be incorrect to refer to the incident as a fight. He weathers the cut with stoic grace, lures the wielder of the blade into the parking lot of the Bandstand under the false pretense of giving him the honor of a mano a mano throwdown, and then walks back inside, closing the gates of paradise behind him with a row of mountainous bouncers.

The real first fight occurs about 15 minutes in, when Dalton first arrives at the Double Deuce. Let us leave aside the manner in which the fight begins, for now; suffice it to say it involves the violation of a verbal contract and a subsequent falling-out between the negotiating parties. Let us also avoid discussion of the fight’s particulars, each of which will likely receive an entry of its own. Here our focus is on the fight’s gestalt. As much as the Shirtless Man or the Four Car Salesmen or the Bouncer Fame Index, it is an indication of the kind of movie you’re watching, and the most visceral and ambitious one at that. And it indicates this: You are watching a movie in which barfights achieve the colossal scale and cacophonous visual intensity of a painting from the Flemish Renaissance.

While, again, avoiding the instigating incident and the individual fight choreography beats, the effect of the first fight is intoxicating—a vertiginous ramping-up of wanton physical stupidity and destruction, from a starting point that is incredibly stupid itself, that simulates the effect of consuming an heroic amount of intoxicants in a time short enough to be the length of a song from Wire’s Pink Flag.

The first time I watched Road House I’d heard about it for a couple of years from the friends who wound up introducing me to it, but really had no idea what the fuss was about. By the time the first fight was over I wondered no longer. While I imagine there are those who do not give themselves over to the movie after this scene, I was not one of them, nor do I truly understand what it would take to be one of them. There’s no resisting the howitzer blast of shattered bottles, smashed tables, flying bodies, and punched heads you witness here, nor the rogues gallery of one-off stuntpersons who produce them.

And while Dalton himself stays out of the fray, watching it all unfold with the sangfroid only America’s second most famous bouncer could muster, you the viewer are afforded no such luxury. You pinball around with the camera as every act of stupendously dumb violence is rubbed right in your face. As a collection of individual moments, shots, characters, punches in the head, it’s truly impressive.

But when the camera pulls back and the full scale of the devastation is revealed for the first time? Breathtaking. Staggering. Clarifying. In that one moment you mentally whip-zoom from the trees to the forest, the way you might look back at a particularly harrowing stretch of events in your life and think “my god, how did I ever make it through?” The parts overwhelm moment to moment. The whole overwhelms on a whole other level, yet none of the parts are concealed. Everything is happening.

And you’ve emerged on the other side, with roughly a Tilghman’s eye view of the conflagration. You see the magnitude of the task Dalton has taken on, even as he casually strolls through the still-raging slobberknocker to confer with the bar’s owner. You see the movie you’re about to spend another hour and a half watching, itself a collection of individual moments, shots, characters, and punches in the head—just as chaotic as this one image, and just as cohesive a statement.

024. Mr. Clean

January 24, 2019Dalton’s first visit to the Double Deuce is, it’s reasonable to assume, a representative view of the establishment’s clientele. He is harassed in the parking lot by a gang of bikers angry at him for driving a Mercedes instead of Detroit steel. Inside the bar he passes two women pawing at their noses clearly after powdering them in the ladies’ room. (A minute or two later we see them approach the Double Deuce’s resident drug-dealing waitress to purchase the cocaine they just used, a transaction she tells them she will complete in the ladies’ room. I suppose it’s possible they just needed more and not that they entered the Moebius, a twist in the fabric of space where time becomes a loop.) He sees a hayseed who looks like Jeff Foxworthy sexually harass his future friend and Dionysian acolyte Carrie Ann. He watches Regular Saturday Night Thing Steve refuse to break up a rolling-around-on-the-ground fight because the participants are brothers.

The first person to actually acknowledge the presence of Dalton inside the Double Deuce is a man who is cueball Kojak bald, at a time when that was still unusual enough to be striking. When Dalton parks himself at the corner of the bar nearby, this fellow gives the newcomer a polite wave hello. He then stands up, tucks his chin against his neck in the fashion of someone who has just involuntarily re-tasted an hours-old meal, and raises his eyebrows like he’s surprised he’s still mobile. He is drunk as a lord. He toddles away in the fashion of a person who is mustering literally all of his physical and mental energy just to make it to the bathroom without exploding out of both ends.

I think of this guy as Mr. Clean, for obvious reasons, and for lack of a better descriptor. And why not? Despite being both friendly and nonviolent, he’s nevertheless exactly the sort of 40-year-old adolescent, power drinker, felon, and trustee of modern chemistry Dalton will go on to tell his underlings it is their job to expel from the Double Deuce forever. Dalton is here to clean up the likes of Mr. Clean.

Yes, Mr. Clean offers Dalton a comparatively warm welcome, before lurching out of frame and out of the film forever. What of it? This will hardly be the last time that those Dalton must destroy approach him in the guise of friendship. In the words of Dalton’s First Rule: Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected. Including a polite little wave hello.

019. Staff

January 19, 2019Brad Wesley isn’t the only man in Jasper, Missouri with a goontourage. The employees of the Double Deuce whom Dalton does not fire when he assumes the role of cooler can generally be counted upon to have his back. I don’t think this is just the dubious whipped-dog loyalty of working stiffs to the middle manager who spares their jobs while shitcanning other people instead, either, though god knows we’ve all been there. Dalton brings out the best in good people and the worst in bad people. He’s a moral refinery. Here are the people who emerge purified from the kiln of his character. Most go unnamed, but let us not allow them to go unsung.

Jack

Bouncer. Expressive eyes. Quick on his feet, literally and figuratively. Played by Travis McKenna, whose body type sets him up as the opposite number to Brad Wesley goon standout Tinker, but never used as comic relief (except maybe once, when Brad Wesley goon standout Jimmy uses his prone body as a fulcrum to pole-vault onto the stage at the Double Deuce with a pool cue) and shows much higher levels of emotional intelligence. Fastest-moving character in the film save for Dalton himself. Visibly receptive to Dalton’s advice and instructions. Demonstratively appreciative of his fellow employees’ talents (he’s positively delighted to discover Carrie Ann’s singing voice). Frequently is the first to warn Dalton of Brad Wesley’s bad acts. Most likely to become the Dalton to Dalton’s Wade Garrett sometime down the line. Steve the Horny Bouncer whom Dalton fires due to his regular Saturday night thing calls him “Bear.” No one ever says this character’s name in the movie.

Younger

Bouncer. Just a big ol’ mumble-mouthed meathead, played by Roger Hewlett. Politely raises hand to ask a question during Dalton’s orientation session. Has the least screentime of the three bouncers, leaving the nature of his skill set largely to the imagination. The guy I would least like to tangle with personally, as he seems like he might not notice he’d beaten you to death until long after it was too late. No one ever says this character’s name in the movie.

Hank

Bouncer. The most visually dashing of Dalton’s crew, and the most openly fanboyish about his renowned exploits. Reenacts Dalton’s infamous throat-ripping maneuver, alerting us to this chapter in his checkered past. Frequently takes point in breaking up hostilities prior to Dalton stepping in. Smokes a lot. Played by future real-life murder-suicide perpetrator Kurt James Stefka, because every Lost Highway needs a fucking Robert Blake. No one ever says this character’s name in the movie.

Carrie Ann

Waitress. Singer. Breakfast delivery person. Engine of pure erotic power. Pal and confidante. Just a kickass character in every way. It helps that people do say her name in the movie, that’s for sure. Played by Kathleen Wilhoite and god bless her for it.

Stella

Waitress. Has that weird “German schoolgirl” vibe (description courtesy of MST3K/RiffTrax genius Mike Nelson) common to waitress types circa the filming of the original run of Twin Peaks, which you could probably convince anyone she was a character in as well. Tosses a bottle and hits a nitwit at one point. Played by Lauri Crossman. No one ever says this character’s name in the movie.

Ernie Bass

Bartender. Keith David. Unrealized potential. For some reason people say his name in the movie, though considering how badly he’s wasted who knows why.

The Nameless Bartender

Bartender. Prominent throughout the film. An original employee of the Double Deuce, unlike Ernie, who is brought in when things are flush. Multiple lines of dialogue. No one ever says this character’s name in the movie. No one ever bothered to name this character for the movie. Played by James McIntire, uncredited. There’s gotta be a story here, man.

Cody

Lead singer and guitarist of the Jeff Healey Band. Played by Jeff Healey. Not named Jeff Healey in the movie, though. Plays pretty good for a blind white boy, according to Dalton, with whom he has a long-standing working relationship. Possibly the person who recommended Dalton to Frank Tilghman, though this is never established and neither man seemed to realize the other would be working at the Double Deuce at the time of Dalton’s arrival. Adds much-needed verisimilitude and is a lot of fun to watch and listen to, even if acting is not Jeff Healey’s first calling. Recently I discovered that it’s Cody, not Dalton’s landlord Emmet, who sits on the shore as Dalton and the Doc skinny dip in that water at the end of the movie. They did seem pretty close, certainly.

Cody’s Drummer and Cody’s Bass Player

Drummer and bass player of the Jeff Healey Band. Played by Tom Stephen and Joe Rockman, who are amazingly not related despite both looking like they rolled off the dollar-store Eric Bogosian assembly line in the same batch. Silent observers of the events of the film, a mute Greek chorus. Great hair. No one ever says these characters’ names in the movie, not even “hey, Cody’s Drummer” or “Congrats on the chickenwire coming down, Cody’s Bass Player.”

???

??? That’s him on the left. I don’t know who this man is. This man is in a grand total of one scene, Dalton’s orientation session. This implies he’s an employee of the Double Deuce, but he is never seen before or since. No one ever says this character’s name in the movie. No one ever says his name outside of the movie. No record exists of the actor who played him. No evidence of his existence can be found anywhere beyond these few minutes of footage. Where he’s from the birds sing a pretty song, and there’s always music in the air. LET’S ROCK

018. Keith David

January 18, 2019This is Keith David. In 1982, he played Childs in John Carpenter’s The Thing. Childs is the primary antagonist for the main character, R.J. MacReady, played by Kurt Russell. I mean, everyone is everyone’s antagonist, but Childs is the person who’s the most openly suspicious of MacReady and hostile to the way he sort of naturally slides into a command position. It’s too much to say the two men must learn to work together to have any hope of defeating the shape-shifting alien that has infiltrated their remote Antarctic outpost, since there’s no learning involved, but they must work together, that’s for sure. The extent to which they do or don’t is, in the end, the final question asked by the film. David plays the character like a pot of water set to boil at any moment; his chemistry with the less demonstrative but no less gruff and argumentative MacReady is considerable, and essential to the success of the movie, which is one of the greatest horror and science-fiction films ever made.

In 1988, David reunited with carpenter for They Live, in which he played Frank. Frank is the primary antagonist for the main character, Nada, played by “Rowdy” Roddy Piper. Again, everyone is everyone’s antagonist in this film, another stone sci-fi/horror classic about distrust and paranoia in a world where alien invaders can look just like you and me. Beneath the anti-consumerist, anti-capitalist, anti-cop, anti-corporate-media agitprop for which it has become justly famous, They Live takes The Thing‘s survival-horror cabin-fever claustrophobia and simply expands it outward, until the entire planet is the remote outpost on which the last sane men and women are trapped. Having slipped on a specially treated pair of sunglasses that enable him to see the true faces of the alien overlords and the mind-numbing subliminal messages they’ve implanted in every TV screen, billboard, and printed page, Nada is one such sane man, but he can’t fight back alone. He needs Frank, a guy even bigger and tougher than himself whom he met while they made just-above-starvation wages at a construction site, to put on the sunglasses and see for himself, so they can join forces and fight the real enemy. Frank, understandably, thinks Nada is out of his mind. The only way he’ll wear the damn glasses is if he is beaten up badly enough to literally be unable to stop Nada from putting them on his head. This is what happens, during an ugly, sloppy, seemingly endless one-on-one brawl in an alleyway that lasts for six full minutes. It’s just Roddy Piper and Keith David whaling on each other, over and over, for roughly the length of “Hey Jude.” In the end, Frank is made to see the truth, and the two combatants become allies. It’s one of the greatest fight scenes ever filmed.

In 1989, David joined director Rowdy Herrington and star Patrick Swayze for Road House, a film that is to men punching other men in the face and torso what the children’s book series Clifford the Big Red Dog is to big red dogs named Clifford, in which he plays Ernie Bass. Ernie is not a bouncer. Ernie is a bartender. He says “Whiskey’s running low.” I think maybe he says hello to Dalton at some point but I’m not sure. He does not fight anyone, at all, ever. Not one punch. Not even a raised voice. Who knows, though. Maybe he helps guard Jasper, Missouri from the forces of evil by Dalton’s side after the end credits roll. It’s possible, anyway. Why don’t we just wait here for a little while. See what happens.

017. The Double Douche

January 17, 2019Dalton has worked at the Double Deuce for a while now, and business is booming. The place is packed every night. The bartenders and bouncers wear jaunty red shirts as uniforms. The band is out from behind the chickenwire. The facade has been remodeled to look like a place the gang from Saved by the Bell might visit. There’s just one problem: Brad Wesley has cut off the liquor supply. Dalton, an excellent cooler but not the most excellent cooler, knows this is no job for one man. He makes a call. (He has sex with the Doc.) Then, as Dalton requested, Wade Garrett arrives. Senpai has noticed him.

Wade Garrett is played by Sam Elliott, and what you’re picturing is almost what you get. The voice is there. The sense that you’re looking at a person who’s more beef jerky than man is there. But this isn’t the fine upstanding cowboy who wishes the Dude wouldn’t use so many cusswords. (Nor even the actual pitchman for beef.) Wade Garrett is a bit dangerous, a bit sleazy, a lot sexy. “Louche” might cover it.

So when Wade Garrett pulls up on his motorcycle, he doesn’t so much dismount the bike as ooze off of it. You can all but hear his bowlegs creak and stretch, smell his two-day post-shower aroma spiked with cigarette smoke and exhaust fumes and hot asphalt, feel him adjust his hips to ensure he’s doglegging in the proper direction within those skinny black jeans.

Wade Garrett looks up at the Giuliani Times Square marquee Frank Tilghman has erected over the former dive bar where young Dalton works, runs his hand over his greasy gray hair, and reads the name aloud: “The Double Douche.” [Sic.]

Why does he pronounce it this way? On one level I assume it’s a tip of the hat to the all-time god-emperor of pronouncing “deuce” as “douche,” Manfred Mann’s Earth Band’s version of the early Bruce Springsteen composition “Blinded by the Light.” Wade does have his shades on, and it is very bright out.

But it’s more than that. It’s a demonstration of Wade’s contempt for anything but the work of cooling itself. You can wrap it up like a Deuce, or a Douche if you will, but beating up the people who beat other people is what he’s here for. No delusions, no pretensions. He came to fight. To quote the man himself when he’s asked “Are you gonna fight, dickless?” a couple minutes later, “I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick.”

And it’s a signal that whatever his affection for his protégé Dalton, he shares little of the younger man’s philosophical outlook. It’s hard to imagine Wade Garrett telling anyone that being called a cocksucker is just “two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response.” Wade is too much of the wild man, too much the heir to Mifune in Seven Samurai. Wade’s world is one of George Carlin’s seven words, several of which he lets fly before his untimely demise. It’s a world of sweat and blood and sexual fluids. Those are things he understands. Those are things he treasures.

This is not to say that Dalton is a slacker in any of those departments—far from it. It’s just that he maintains a certain detachment from it all. Not so Wade. He’ll pull his sidekick’s ass out of the fire one minute and compliment his sidekick’s girlfriend’s ass the next. He’ll show a woman he just met his pubic hair in order to reveal a wound incurred from a previous woman who was presumably well acquainted with his pubic hair before things went south, so to speak.

Speaking of bad breakups, the horrible crime of passion that haunts Dalton? Wade blames the woman whose husband Dalton murdered with his bare hands more than Dalton himself on account of her never revealing her marital status, and sees it as a simple matter of kill or be killed. Yet he’ll expose intense feelings like that only when pushed by the man closest to him, Dalton himself. Otherwise Wade Garrett is, as Billy Joel would put it, quick with a joke or to light up your smoke. He’s still cracking wise the last time we see him alive, after he’s been beaten half to death.

Put succinctly, Wade Garrett the type of guy to ride hundreds of miles to the rescue of his best friend, then make a sophomoric douche joke when he arrives. There are many ways to be an itinerant bouncer-sage in this world. The path of Wade Garrett is but one, as valid as any other.

016. A Great Buick

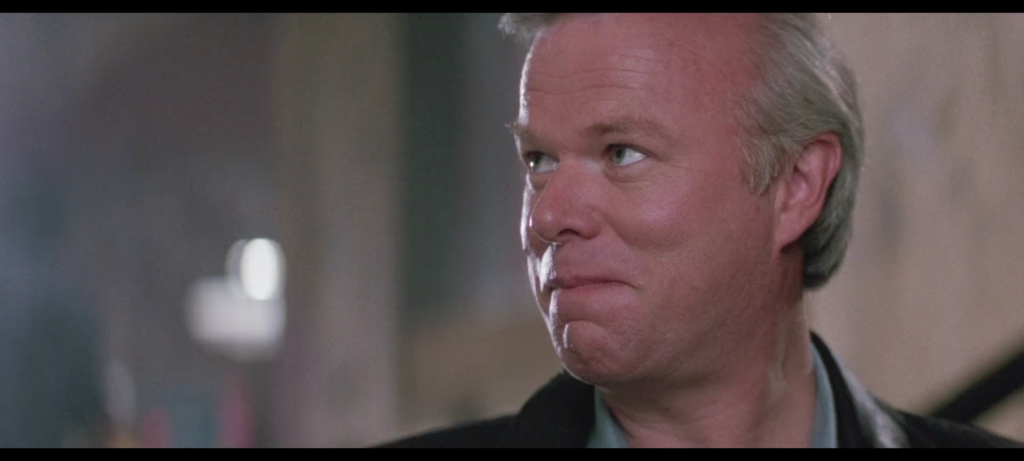

January 16, 2019Where to begin with Frank Tilghman. As played by Kevin Tighe, silver-haired proprietor of the Double Deuce is a singularly unpleasant person to observe. He walks like a man who’s sneaking up on you even when he’s coming at you straight on. His smile is stuck in the “leer” setting. His eyes gleam with the dubious good cheer of a man who knows a secret enjoyable only to himself, like the retiree who leaves out bowls of antifreeze for the neighborhood cats, or the assistant manager at the Stop & Shop who occasionally rubs his genitals on the produce. He is the first main character we meet, when he shows up at the Bandstand to hire Dalton; anyone who doesn’t assume he’s the villain from his look and behavior during that sequence should be a prime target of the social-engineering hackers your office information-security training module warned you about. Yet he isn’t the villain, because somehow there’s an even weirder and more inappropriately chipper old man out there waiting for us.

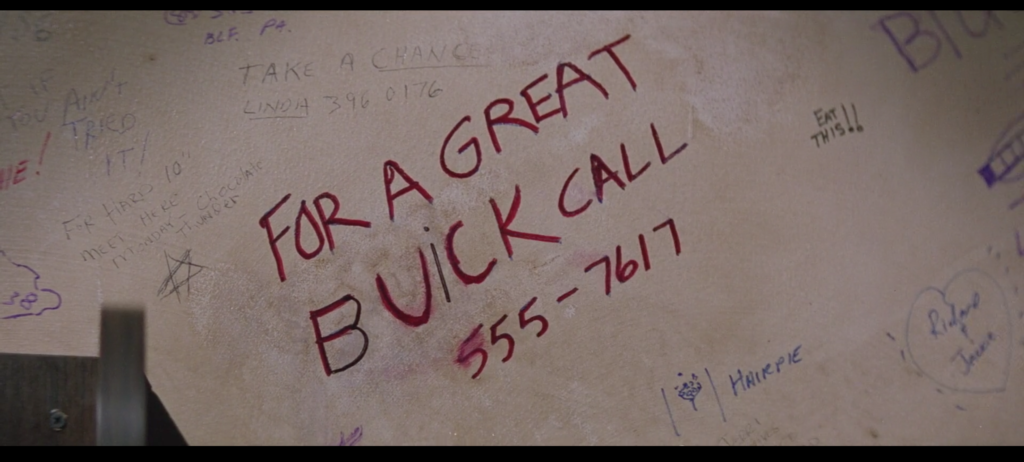

But until we meet Brad Wesley, the only proof of Tilghman’s good intent we have—virtually our only glimpse of his interior self at all—is when he changes the word “FUCK” to “BUICK” in the graffiti next to the Double Deuce’s payphone.

I won’t say I know what you’re thinking, because when Tilghman’s the topic of discussion all thoughts are permitted. But you might be thinking “Changing an obscene lavatory-wall come-on into a classified ad for a used car isn’t necessarily Good Guy behavior. The whole thing smacks of Capital.” That much is true. It’s the way Tilghman goes about this completely ridiculous act of appropriation that indicates his true character.

After hanging up the dangling handset back in the cradle, he notices the vulgar legend “FOR A GREAT FUCK CALL 555-7617,” which stands out amid all the other crude scribbles (“KATHRN THE GREAT & MR. ED” is written in white nearby, for instance) due to its size and bright red color. Looking over his shoulder, as if he’s the dirty-minded solicitor who might get caught by the owner of the bar, he produces a black Sharpie, unconvincingly converts the “F” to “B,” and slips an “I” between the “U” and the “C.” Voila: FUCK is now BUICK. Somewhere out there, the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri rest a bit easier. (They’re most likely in Jasper, Missouri, admittedly.)

Then, before smiling in self-satisfied fashion and walking away, comes the coup de grace: He adds a little dot over the “I.” Yes, everything is in all caps, and no, he doesn’t care. He’s going to dot his I’s and cross his T’s, goddammit, even if it costs him in terms of verisimilitude. A man with pretensions to class that unwavering is absolutely a man who’d hire a wandering philosopher-bouncer to clean the joint up for a mid-six-figure yearly salary with no ulterior motives whatsoever. I respect this strange man. Not enough to risk death every night so that his house band doesn’t have to play behind chicken wire for safety’s sake anymore, perhaps, but I respect him.