Posts Tagged ‘road house’

004. Doc

January 4, 2019Fantastic fiction often asserts that forces awesome, alien, or profound enough to overwhelm our senses will be processed by our puny brains in ways we’re capable of processing instead. The erratic movements and sudden disappearances of UFOs are how we see extradimensional travel. Vast unspeakable intelligences present themselves to us as dragon-winged squid-gods. Fire and life incarnate themselves in a flaming bird shape and a costume color-scheme change.

But can it work in the other direction? When faced with the inexplicable, can our minds process it into something more human, not less?

The life of Dr. Elizabeth Clay in Road House can be divided into five phases. She meets our hero, Dalton, when he’s admitted to the hospital where she works for the treatment of a knife wound he incurs on early in his tenure at the Double Deuce. After telling him the cut will require nine staples, she rattles off a list of previous injuries from his medical files, which he carries around with him. (“Saves time.”) She offers him a local anesthetic, which he refuses. (“Pain don’t hurt.”) She notes that his medical files say he graduated from NYU, where, he tells her, he studied philosophy. (“Man’s search for faith, that sort of shit.”) Given the damage that’s been done to his body, she facetiously asks him if he’s ever won a fight. (“Nobody ever wins a fight.”) Furthering one of the film’s recurring jokes, she says that she figured someone in his line of work would be bigger. (“Gee, I’ve never heard that before.”) Perhaps because nearly everything he says would look good as a back tattoo, she accepts his offer to take her out for coffee in the middle of all this.

Next time we see the good doctor, she shows up at the Double Deuce for their date, in a dress that looks like something Billy Joel and his first love ordered a bottle of white, a bottle of red over. She arrives in time to watch him finish beating the tar out of several of Brad Wesley’s goons alongside his fellow bouncers. During their date she brutally negs him for getting paid to hurt people, and for acting like a Nice Guy when he clearly isn’t. Perhaps impressed by how he tosses money on the counter of the diner where they’re eating so that the grumpy manager will allow a falling-down-drunk old man to sit there a while longer, or the good-natured way in which he reacts to discovering his enemies have rammed an entire stop sign through the windshield of his car, she gives him a chaste but heartfelt kiss goodnight before leaving. (He gives her the same little salute he gave the Second Car Salesman of Jasper, Missouri as she drives off.)

She meets up with him at the Double Deuce again a few scenes later, by which point Dalton has pretty much single-handedly reversed the place’s fortunes, which you can tell because the bartenders are wearing uniforms and there’s no longer any chicken wire around the bandstand to protect the performers from the audience. They go back to his place. He turns on the radio and, after they both reject Bullet’s “I Sold My Soul to Rock n’ Roll,” settles on “These Arms of Mine” by Otis Redding. They exchange five or six sentences about her Uncle Red, who raised her after the death of her parents, and her failed marriage. Then they have sex; he’s inside her, standing up, before they so much as kiss. She laughs while they fuck, like she’s in on the joke. Later that night they fuck again, on the roof, in full view of Brad Wesley, who lives across the water, and whose house she looked at ruefully shortly after arriving at Dalton’s apartment because he was the person she had the failed marriage to. (Though their relationship is confirmed, the actual fact that they were married is never stated outright, but the vacuum-sealed logic of the film allows no other possibility; there’s not enough room in anyone’s life for two major former disastrous love interests.)

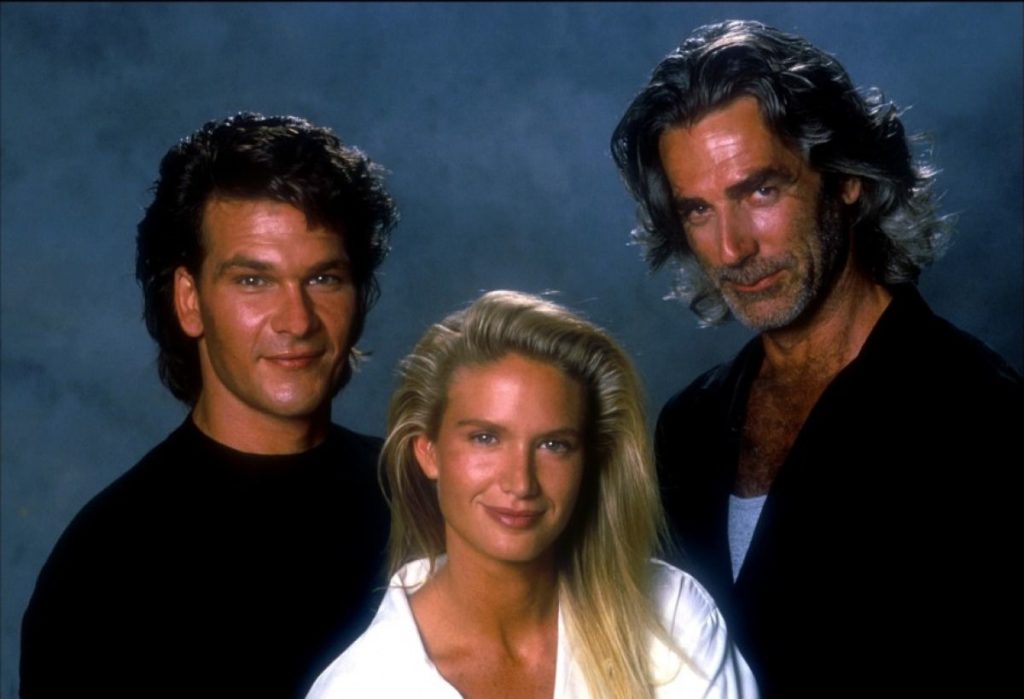

When Dalton’s mentor Wade Garrett comes into town to help him in his battle against Wesley—Elizabeth has become a focal point in that grudge, and in Dalton’s desire to stay in town and take Wesley down rather than simply picking up stakes and moving on when things get ugly, as Wade advises—the two men and Elizabeth spend the night on the town, drinking beers and swapping stories about their old antics and injuries (the two are inseparable), which at one point involves Wade unbuttoning his jeans and revealing the dark thatch of his pubic hair to show her a scar on his hip that a woman gave him. They pull an all-nighter, during which Wade and Elizabeth dance in a diner (not the previous diner, nor the place they spent the night talking and drinking in, nor the Double Deuce, but a fourth dive altogether) and he comes on to her pretty heavily, with just enough plausible deniability that everyone can play it off with a smile. The sexual tension between all three is just insane, though it’s cut short by the start of the work day. (“Don’t mean to bust up the party, but my shift starts in a couple of hours—thought I’d go home, get some sleep,” says the trauma surgeon after spending the past five or six hours drinking.)

Elizabeth’s final emotional beat in the film is as the unhappy go-between in the Dalton/Wesley feud. She chastises Brad (she’s the only person who calls him that) for destroying Strodenmire Ford with a monster truck, and warns Dalton that if he’s trying to save the townsfolk from Wesley, “Who’s gonna save them from you?” Actor Kelly Lynch’s commitment to this line, which she shrieks at the top of her lungs, is so total that when Wesley’s lead goon Jimmy blows up the shack where Dalton’s landlord Emmet lives the next moment, at first it seems like she Carrie‘d the place. When Dalton kills Jimmy by ripping his throat out with his bare hands, she checks to make sure the man is dead, then leaves, horrified, and refuses to leave town with Dalton when he tries to convince her to do so at the hospital the next day. For some reason she goes to Brad Wesley’s house during the middle of Dalton’s killcrazy rampage through his army of goons; her arrival prompts Dalton to not tear Wesley’s throat out, which gives Wesley a chance to go for a gun to finish Dalton off, but fortunately four old men show up with shotguns and Sonny Corleone the shit out of the guy.

After she watches her ex-husband die during an attempt to kill her current boyfriend-ish guy, the doctor and Dalton are reunited and skinny-dip in front of his landlord Emmet happily ever after.

Every time I watch Road House I grow more and more fond of the Doc. And why wouldn’t you? She’s the smartest and most together person we meet, having one of the few jobs anyone holds outside of the automotive, alcohol, or beating-people-up industries. She has a good head on her shoulders regarding the lunacy of Dalton and Wesley’s blood feud, which has involved the total destruction of at least three buildings in town and the severe injury of dozens of human beings even before people start dropping like flies. Removed from the French braid she wears it in for work, her hair does this cool thing where it sticks out on the sides like an old Barbie doll. She’s one of the few human beings who could get bare-ass naked next to in-his-prime Patrick Swayze and hold their own.

However, she also accepts a date from a masochist who’s constantly getting his ass kicked, which she knows because she meets him while stapling his latest knife wound. She holds his job in open contempt and mocks the idea that he’s a force for good in town even when they’re getting along and used to be married to his arch-enemy, whose murder during the process of his attempted murder of Dalton she witnesses before settling down with Dalton for good. She goes into work at a hospital on two hours of sleep after spending the small hours pounding Miller High Lifes. Even by the standards of Road House, a film about famous bouncers, her behavior is hard to recognize as that of a normal human person.

Yet when I think about her, it’s always in terms of “Wow, way to put him in his place,” or “power move,” or “wearing that dress takes guts,” or “fucking before kissing, right on, this is a person who knows what she wants,” or “she must really love her uncle to hitch her star to Jasper, Missouri’s wagon on his account, I bet he was a great dad to her” or “she patches up Dalton’s knife wound but the next time we see her at work she’s looking at x-rays of someone’s colon, what’s her medical specialty,” or “she could absolutely talk Dalton into making out with Wade in front of her and she knows it, and just sits with it because knowing it is all the satisfaction she needs,” or “I wonder what she saw in Brad Wesley,” or “I bet she went to an Ivy League medical school because she’s just a little condescending when she talks about Dalton going to NYU.” In other words, things you might think about a normal human person, and a very interesting one at that. Confronted with Road House, the mind transmutes chaos into character.

003. The Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri

January 3, 2019If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig. —Uilliam M. Bricken, Jr.

An English professor of mine used that self-reflexive riddle to illustrate the way Christ’s parables are both medium and message: The second the concept behind the parable clicks, so does the larger point about ethical behavior or spiritual enlightenment.

In his book The Three Christs of Ypsilatnti, psychologist Mark Rokeach recounts an experiment, which he would later apologize for and reject as unethical, in which he placed three men who believed themselves to be Jesus Christ in regular group therapy sessions in hopes that encountering each other would shatter their delusions, to which end he occasionally manipulated them directly by concocting imaginary elements of their collective story himself. The experiment was unsuccessful.

This man is Big “T” of Big “T” Auto Sales, or so it seems safe to assume. We meet him around 17 minutes into the film, as he watches The Patty Duke Show on his office television while preparing to eat his lunch. He then notices our hero, Dalton, checking under the hood of a beat-up old car in the lot. “She’s a runner!” shouts this walrus-looking sonofagun as he strides out to meet Dalton face to face, treating the singular requirement of any used car sale—that the car being sold is capable of movement—like a selling point. Dalton drives a Mercedes when he’s not on the job, but since angry patrons of the bars at which he serves as cooler tend to take their frustrations out on his car after they’re ejected, he replaces it with a cheaply bought beater when he’s got a gig. He takes the car. We never see Big “T” again.

This man does not have a name, not that we’re given to know anyway. We meet him about one minute after we meet Big “T.” This fellow presides over some kind of automobile junkyard Dalton goes to not to purchase a used car, which he could have done here since used cars are visibly on sale in the background, but to stock up on spare tires, since people who are pissed off that he smashed their face through a table because their girlfriend was dancing on another table often slash his tires in revenge. Dalton loads the trunk of his new old car with tires and gives the proprietor a little salute, which the old man returns. We never see this man again.

This man is Red Webster, proprietor of Red’s Auto Parts. We meet him around 33 minutes into the film, after which he becomes a major character. His store is the closest business to the Double Deuce, with which it shares some kind of vast dirt parking lot or road or whatever it is despite being about a football field away. His niece is Dr. Elizabeth Clay, former love interest of Brad Wesley and, soon, current love interest of Dalton. He is Dalton’s primary source of information on the protection racket run by Brad Wesley under the guise of civic improvement. Dalton goes to Red’s store to order a new windshield and buy a new antenna for his car after both were destroyed by angry ex-patrons of the Double Deuce the night before. This is the third scene in which Dalton makes an automobile-related purchase, and the third business establishment at which he does so. The movie is not quite 35 minutes old.

This man is Pete Strodenmire, proprietor of Strodenmire Ford. We meet him around one hour and 24 minutes into the film, at a hastily convened meeting of Jasper business owners, plus Dalton and Elizabeth, to discuss the prior night’s destruction of Red’s Auto Parts in an arson ordered by Brad Wesley. There are seven people at this meeting. Four are Dalton, Elizabeth, Dalton’s nominal boss Tilghman (seen above in the background), and Elizabeth’s uncle Red. The other three, including Strodenmire, are people we’ve never seen before; the two who aren’t Strodenmire have no lines, and we never see them again. The next time we see Strodenmire, Brad Wesley has ordered one of his goons to run over the man’s entire glass-enclosed showroom of new cars with a monster truck, which he does with glee. Strodenmire winds up being one of four men—along with Red, Tilghman, and Dalton’s nominal landlord Emmet—who murder Brad Wesley, the film’s antagonist, with shotguns during the climax. Again, we meet him an hour and a half into a two-hour film that has already included three other car or car-parts salesmen.

This man is Emmet. We meet him about half a minute after we meet the man from whom Dalton purchases tires, when he rents Dalton a barn-loft apartment that must have cost $50,000 dollars to build for $100 a month. He doesn’t sell cars or car parts, but you can see how he and the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri share a similar aesthetic.

Road House is a movie about a road house, that much is true. It’s not a movie about roads, however, nor about what you drive on them. (Much more time is spent showing Dalton buying cars, parking cars, and buying car parts to fix what happens to the cars after they’re parked, than is spent showing anyone actually driving cars.) Thus, the film’s maximalist approach to automotive retailers is striking, and bears contemplation.

Could Dalton’s trips to fully four different stores for his vehicular needs have been consolidated to, say, two, perhaps the ones owned by the two men who wind up saving his life from the character played by Ben Gazzara (John Cassavetes’s Husbands)? Yes.

Would this have been an easy way to establish Strodenmire, who I stress fires a shotgun into the body of the movie’s antagonist and inflicts a mortal wound, before the movie was three quarters of the way finished? Yes.

Would this have made things less confusing to people for whom men whose vibe is best described as “Old Fart” sort of blend together in an indistinguishable blur of ill-fitting work shirts and bold facial-hair decisions? Yes.

Is understanding that Road House has its protagonist make car-related purchases from three different men (two of whom are never seen again), includes a fourth as a main character when he emerges from a nameless scrum of unknowns when the movie is almost over (and who has never been seen before), and casts weird old coots in all four roles (with weird old coots to spare playing other parts)—that is to say, understanding things that makes no sense—key to understanding Road House‘s unique rhythm in all its concussive dreaminess?

If this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.

002. Brad

January 2, 2019 Here’s what we know about Brad Wesley.

Here’s what we know about Brad Wesley.

He grew up on the streets of Chicago, where he “came up the hard way.”

He came to Jasper, Missouri after serving in the Korean War.

His grandfather was an asshole.

He has one sister, whom we don’t meet.

He has a nephew, Double Deuce bartender Pat McGurn, whom we do.

He has a cousin in Memphis. (This unseen—or is he?—cousin tells him Dalton killed a man down there. Said it was self defense, which Brad doubts.)

He owns a helicopter, an ATV, a red convertible, and a monster truck, all of which he enjoys driving, or paying someone else to drive, erratically.

He loves the song “Sh-Boom.” (The Crew Cuts version, not the Chords version, which if you know Brad is unsurprising.) He can’t stand today’s music, which has “got no heart.” He prefers when bands “play something with balls.”

He employs a squad of goons for whom he enjoys throwing topless poolside bacchanals, and whom he also enjoys beating up arbitrarily when they displease him for reasons such as bleeding too much.

His favorite goon is Jimmy, a martial artist who I believe to be his bastard son. Strictly speaking this is not supported by the text—Wesley refers to all of his goons as “my boys”—but it’s in the eyes.

He’s “dating” a woman named Denise, whom he beats up for coming on to our hero Dalton. Later he has her do an erotic striptease at the Double Deuce to teach Dalton a lesson (?).

He used to be married to Dr. Elizabeth Clay, a surgeon or gastroenterologist with whom Dalton becomes involved after she treats him for several wounds incurred in his first barfight at the Double Deuce.

He lives in a waterfront mansion across a lake or river or something from the farm or ranch or whatever where Dalton rents an extravagantly appointed open-air apartment from a bearded old codger named Emmet who sleeps in a union suit. This provides him with a convenient vantage point from which to buzz the old man’s horses with his chopper or sit in a rocking chair and watch Dalton and Elizabeth have sex on the roof of a barn.

Now’s a good time to mention he’s played by Ben Gazzara, a frequent collaborator of John Cassavetes who created the role of Brick in the original Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

He alternates between light-colored suits of the Boss Hogg variety and the fussily sporty apparel of a weekend warrior. As they do in the wardrobes of many characters in this film, boots play a disproportionately large role in his ensembles.

He has a trophy room full of the stuffed carcasses and mounted heads of both exotic and domestic animals that would shame a Trump son.

He runs a glorified protection racket called the Jasper Improvement Society that keeps all the local businesses under his thumb, including the auto parts store run by Elizabeth’s uncle Red Webster.

He controls alcohol distribution in the region, which provides him with a line of attack on the Double Deuce after his nephew Jimmy is fired for skimming the till.

He feels that his many achievements in building the town of Jasper up from “nothing” have entitled him to get rich off its inhabitants.

Here are those achievements, quoted verbatim.

I brought the mall here. I got the 7-Eleven. I got the Fotomat here. Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me! You ask anybody, they’ll tell you!

Road House is the story of one bouncer’s quest to free a small town from the iron fist of the guy who is on the verge of opening the area’s first JC Penney. Over half a dozen men will die for this.

001. Fame

January 1, 2019 Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

So that tells you something about the kind of film Road House is: It respects the people who beat up people who beat up other people in bars so much that it affords them significant renown. Other men will fly across the country and offer these men hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for their services. Barfolk, for want of a better term, whisper their names in reverent awe. In the land of the blockheaded, the two-fisted man is king.

Because their reputations precede them, or because to invoke them inaugurates the ritually contracted cycle of redemptive violence for which they’ve been hired, the bouncers of Road House are reluctant to share their names.

“You got a name?” asks Carrie Ann, waitress at the Double Deuce, the ultraviolent Missouri honky-tonk at the heart of the story. “Yeah,” answers our hero.

“What’s your name, buddy?” asks Pat, the Double Deuce’s thieving failnephew bartender, who is played by John Doe of Los Angles punk institution X. “Coffee, black,” responds our hero.

When he conducts his first official bouncing during his tenure at the Double Deuce by smashing the face of a man with a switchblade and a Hawaiian shirt through a table adjacent to the one on which this man’s girlfriend has been dancing and thus lowering the overall atmosphere of class in the establishment, it falls to our hero’s blind white blues-playing guitarist friend Jeff Healey (appearing as himself) to reveal his identity to the amazed, and in several cases visibly aroused, patrons.

“The name,” he says, “is Dalton.”

Dalton is by this point in the film known to the Double Deuce’s staff, over whom he’s been given absolute authority by the bar’s bizarre owner Frank Tilghman. “What he says? Goes,” Tilghman tells his employees.

“It’s my way or the highway,” Dalton concurs.

The first person to learn his identity other than Tilghman himself is Carrie Ann, who powers through our hero’s extremely badass rebuff as described above and gets him to name himself, the way Superman tricks his gnomish extradimensional enemy Mr. Mxyzptlk into saying his own name backwards to eliminate him. (Carrie Ann has no such goal, of course; it is perhaps for this reason that she is rewarded later in the film with a glimpse of our hero in the nude. to which she reacts with slackjawed lust so powerful, courtesy of actor Kathleen Wilhoite, that it all but glows with its own internal erotic energy.)

“Shit,” Carrie Ann says when Dalton reveals himself. “I heard a’ you!”

The news spreads like wildfire through the waitstaff, bartenders, and bouncers already in the Double Deuce’s employ, none of whom need its import explained to them. Like I said, a famous bouncer’s reputation precedes him. One man has heard he ripped a guy’s throat out with his bare hands. Another has heard he has balls big enough to come in a dump truck. “Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name,” runs the song from another artifact of Eighties bar culture. Dalton can go anywhere.

Which gives us some indication of his exact level of fame. No one at the Double Deuce recognizes him on sight, which means he’s not so famous that his face alone writes his ticket for him. However, the moment he says “Dalton” in response to Carrie Ann’s query, she immediately assumes he is the Dalton famous for being a bouncer, and not any of the other myriad possible Daltons in the world—B. the bookseller, for example. It’s as if she asked a woman who was new to the Double Deuce for her name, and that woman replied “Gaga.” Only one person leaps to mind.

This separates our hero from his hero. “Wade Garrett’s the best,” Dalton tells Tilghman when the Missouri restaurateur says he’s heard he, Dalton, is the best. “Wade Garrett’s getting old,” Tilghman replies. But age has not dimmed his starpower. Arguably, age is responsible for it. The longer he’s been out there, bouncing and cooling, the more time the dive-bar demimonde has had to put a face to the name.

The face belongs to Sam Elliott, who in this film has long greasy hair, tight black jeans, five o’clock shadow that creeps up his face nearly to his eyes, and a grizzled sexuality that wafts from the screen like a musk. When he arrives at the Double Deuce to help his one-time protégé Dalton defend the establishment against the depredations of Brad Wesley, a local business tycoon and J.C. Penney franchisee played by Ben Gazzara (The Killing of a Chinese Bookie), no one asks his name, because no one needs to. Practically the entire staff stares at him with the wide eyes of children in a film directed by Chris Columbus when he limps bowleggedly into the place looking for his mijo.

Grinning slyly, his eyes twinkling with a sinister delight that seems to be actor Kevin Tighe’s natural mien and has no basis within the character itself, Tilghman looks at this man and says, “I know you.”

Wade Garrett, it can be concluded, has achieved a level of fame so total that even people steeped enough in bouncer culture to know Dalton by name know him by sight. Michael Jordan fame. Michael Jackson fame. Santa Claus fame. Wade Garrett is the best, Dalton tells us. And when Dalton speaks, we would do well listen. It’s his way or the highway. What he says? Goes.

Directed by Rowdy Herrington, written by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin (Academy Award winner, Wag the Dog), released in 1989, directed by Rowdy Herrington (the name bears repeating), and starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara, and an assortment of people with anywhere between one to six lines of dialogue all of whom I adore completely, Road House is one of my favorite movies ever made. I like to talk about it. I hope you’ll like to listen.