Posts Tagged ‘road house’

048. The punchline

February 17, 2019For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

—traditional

“Hey buddy, what are you doin’? Are you gonna kiss ’em or not?”

“I can’t!”

“What do you mean, you can’t?”

“I ain’t got twenty bucks!”

—Road House

This concludes “The Agreement,” a seven-part special Valentine’s Week series. Thank you for reading.

047. A Dream

February 16, 2019Part Six of “The Agreement,” a special Valentine’s Week series

The Agreement is as follows: For the price of twenty bucks (specifically ten a kiss, though the phrasing of The Agreement implies that each breast is to be kissed once rather than one breast kissed twice), Gawker may kiss the breasts of Well-Endowed Wife, with both her and Sharing Husband’s enthusiastic consent. Gawker’s consent to The Agreement appears—appears—to be no less enthusiastic. On the contrary, it’s possible that at the moment he says “ARE YOU KIDDING?!?” no one has ever been more enthusiastic, about anything.

The Agreement brings forth a spirit of joie de vivre in all who participate in or observe it. Gawker, hands full of Well-Endowed Wife, is happy. Well-Endowed Wife, liberally coated with Gawker, is happy. Sharing Husband, by name and by nature, is happy. Heckler…well, Heckler looks like he’s watching The Agreement be fulfilled primarily to keep himself from sliding off the face of the Earth, but whatever part of his brain still functions certainly seems to be happy.

The Agreement is not only happy, however. The Agreement is sweaty. Get the most high-resolution copy of Road House you can find, get a good look at our cast of characters in this scene, and you can smell the salt of physical exertion, the alcoholic tang of beer-induced perspiration, the slightly acrid pit-stink from Gawker’s sleeveless underarms, the how-about-this-heat hail-fellow-well-met forehead dew of a jocular neighbor who seems to be more barbecue grill than man during the warmer months of the year on the noggin of the Sharing Husband, the chemical (or alchemical, if you happen to swing this way and be moved by this kind of thing) interaction between Well-Endowed Wife’s perfume and hair product and moisturizer and makeup her own body’s barely perceptible production of its natural coolant.

What I’m trying to say about The Agreement is that they’re not just having fun, they are into it, man. The absurdity of the whole situation masks this somewhat. My advice? Don’t let it.

Enter the Double Deuce on its own terms. Treat the concerns of its patrons and staff as valid and real. It’s what unlocks the whole film, turns it from “so bad it’s good” to, to, to this. It’s like knocking down some drywall and finding a whole other room, or like finishing The Hobbit and discovering the existence of The Silmarillion. Road House can be enjoyed in any number of ways but the rewards of this approach are—I was gonna say immeasurable, but all of us can count to 365. I know I can. And here, on day forty-seven, you can read the rewards of The Agreement all over its participants’ smiling faces.

Unfortunately, when it comes to the success of The Agreement, there’s only one measurement that counts: twenty American dollars.

Remember these moments, friends. Remember this sweathog happiness. Remember what we had, and could have had, before the bill comes due.

There was a time when men were kind

When their voices were soft

And their words inviting

There was a time when love was blind

And the world was a song

And the song was exciting

There was a time

046. Tableau II

February 15, 2019Part Five of “The Agreement,” a special Valentine’s Week series

I’m sitting in a bar writing this. The bar’s name is Duggan’s. Duggan’s is one of five Irish pubs within a one block radius of my apartment. (Jameson’s, McCarthy’s, Cork & Kerry, and Fallon’s are the others. Arps Tavern too, if you wanna get a little creative with your geography. This does not include the five non-Irish non-pub restaurants with a liquor license in the same area.) What you’re seeing above is not a scene that takes place at Duggan’s, young and dumb and full of cum as its clientele often is. On the kinds of nights when people who are young and dumb and full of cum go out and socialize, anyway. It’s otherwise the province of the shrieking Irish-American racists whose every breath is a betrayal of the Irish liberationary socialist tradition they all believe they support, sans the socialism. Anyway. Duggan’s boasts a relatively genteel crowd even at its most raucous compared to McCarthy’s, the bar whose parking lot abuts my apartment building. I’ve stepped inside there a grand total of once, to see if anyone belonged to the car in the lot with its headlights on. (They did not. At least not that they could remember.) McCarthy’s produces a nightly brawl like Kander & Ebb. I wish I were kidding. Every single night there’s some…what is the Long Island Irish equivalent of the word “guido”? because there really should be one, and “paddy” doesn’t quite cover it. Anyway—every single night there’s some moronic Hibernian, some bog person whose great-great-great-grandma snuck past Ellis Island despite Thomas Nast’s best efforts, screaming “HOLD ME BACK BRO, HOLD ME BACK BRO” or “MY FUCKING SISTER BRO, MY FUCKING SISTER” or “COME BACK COLLEEN, COME BACK COLLEEN” at the top of his lungs about fifteen away from MY HOME where my wife-to-be sleeps and my children play with their toys. McCarthy’s is the kinda place that they sweep up the eyeballs after closing. That’s not where I’m, currently, at. The distinction I’m attempting to draw is that what goes on at the Double Deuce during our first visit to the Double Deuce is intended to be unique to and representative of the Double Deuce. So let’s revisit the image above, and let’s do it from right to left, like we’re reading manga or the Torah. You have Well-Endowed Wife, eyes closed and smiling, thrilling to the sensation of a gormless stranger’s hands on her tits and her husband’s attention and affection resulting from same, I mean she’s transported by it. You have Sharing Husband, cackling with glee, simply could not be happier and more entertained by the spectacle of other men enjoying his wife’s body and his wife’s body enjoying other men. You have Gawker, now and forever Groper just like Donald Merwin Elbert became now and forever The Trashcan Man when he blew those oil tankers in Powtanville (Hey, Trash, what did old lady Semple say when you torched her pension check?), as riveted by this woman’s tits as the first men on the moon were by the earthrise. And—and this is key—you have Heckler, played by Charles Hawke, previously remarkable in this film for hollering “HEY YA PAID TA PLAY PLAY!” AND THROWING A excuse me and throwing a beer bottle at the Jeff Healey Band for the crime of announcing they’re going to take a brief break to urinate in the bathroom rather than piss themselves on stage, and throwing it with sufficient force to shatter it against chickenwire looser than Steve the bouncer’s ID requirements, and saying this with Noo Yawk accent that makes about as much sense in its Jasper, Missouri setting as the idea of famous bouncers, and I’m sure we’ll return to him eventually, but for now let’s look at this miserable bastard, transformed by the spectacle of the tripartite Agreement between Sharing Husband, Well-Endowed Wife, and Gawker/Groper from a belligerent cut-up to fucking Saul on the road to Damascus, transfixed by the sight, blinded by the light, revved up like a deuce another runner in the night, just completely fucking poleaxed by watching one idiot feel up another idiot’s wife. You don’t see that—you might still see it in the desert—but you don’t see it at Duggan’s, and you don’t see it where Dalton is at work. Beautiful in its idiocy as it is, the world Tilghman is building has no room for it. The Elves sail West and the Gawker and Heckler and Sharing Husband and Well-Endowed Wife disappear and so help me god the bar as I sit here writing this the bar is playing “I’m Shipping Up to Boston” by Dropkick Murphys and where is Dalton and Thomas Nast when you need them.

045. ARE YOU KIDDING?

February 14, 2019Part Four of “The Agreement,” a special Valentine’s Week series

“ARE YOU KIDDING?” All caps. No question about it. Actually: “ARE YOU KIDDING?!?” Emphasis in the original. Phonetically, “URYEW KHIHDDINGH?!?”, the first two words slurred into one, the third fired out of a shotgun. An incredulous gasp and a barbaric yawp. The voice of the world’s happiest man, at the very moment he becomes the world’s happiest man, and realizes he’s become the world’s happiest man, simultaneously. The instant when the Gawker crosses the threshold to become the Groper, a three-word doorway he creates and passes through, pulling it shut behind him. A sound effect that accompanies a fantastical contortion of the facial muscles responsible for grinning, taxed to their limit. The noise of a large head on a large neck, jutting forward, physically penetrating the barrier between the potential and the actual. The cry of sweepstakes winners, of hidden-camera prank-show targets, of people who’ve been told this one’s on the house. When you both can’t believe it and you gotta believe! A sound like none heard before or since. An uncommon expression of a familiar sentiment. A singular verbalization of a universal sensation. A sleeveless shirt of a sentence. A microphone held to beer-moistened bluejeans. A line reading greater than any other in a film full of the best line readings in the action-movie canon. The calling card. The fanmaker. The callback generator. The line most likely to be repeated by the inebriated audience. The equal and opposite reaction to “Pain don’t hurt.” A record-player needle dropped into the Venn diagram overlap of drunk, dumb, and horny. A death-row pardon for a man sentenced to never whack it again. The end of “A Day in the Life” but with belches. “Yakety Sax” with a Tristan Chord. Cleavage synesthesia. Happiness is a warm pair a’ attitudes. All you need is twenty dollars and a wet dream. Actor Michael Wise as Gawker in the film Road House, responding to the news that he can kiss the marvelous breasts of a total stranger, provided he pays her husband twenty bucks for the privilege. Perfection.

044. The offer

February 13, 2019Part Three of “The Agreement,” a special Valentine’s Week series

When you write an essay about Road House every day for a month and a half and counting, you learn some wonderful things. As mentioned earlier, Sharing Husband is played by one Christopher Collins (no relation). What I did not know until a reader kindly brought it to my attention is that Mr. Collins was also a voice actor under the name Chris Latta. Not just any voice actor, either. The same guffawing bumpkin who asks “Ever seen a better pair a’ attitudes?” is the voice (screech? wail?) of Starscream from Transformers and Cobra Commander from G.I. Joe, two of the most distinctively abrasive villains in the entire pantheon of early-to-mid-Eighties boy-oriented action-figure commercials in children’s-entertainment form.

Cobra Commander in particular was for me the sound of an entire school of childhood villainy, and a very popular school at that: the chickenshit heel who looked much cooler than he actually was. (Skeletor is the other go-to here.) Any time I had access to a Cobra Commander action figure I felt behooved to swing in the opposite direction and make him competent and fearsome—the lack of respect shown him by his own goons, much less the Joe Team, bothered me that much. Anyone with a mask collection that rad, I reasoned, deserved better. Yet such was Latta’s skill in voicing the character that I maintained the same timbre to the best of my ability even as I substantially changed his skill set. This was not a voice you could shake so easily.

To be sure, the voice Latta/Collins provides for Sharing Husband is less distinctive and more easily imitated than Starscream or Cobra Commander (or the even more eardrum-annihilating D’Compose from Inhumanoids, the …And Justice for All to the other villains’ Ride the Lightning and Master of Puppets). Latta also voiced some of the Simpsons characters during the cartoon’s first season; his Mr. Burns, an instantly recognizable voice that Harry Shearer was nonetheless able to recreate perfectly and play for the rest of the show’s 78-year run, is a creation closer to Sharing Husband’s mark. But learning that Collins was a voice actor by trade, rather than a stuntman as I’d assumed, made his marvelously cartoonish delivery of this scene’s central offer easier to contextualize.

“Tell you what,” he says to the Gawker as the man ogles Well-Endowed Wife and her pair a’ attitudes. “For twenty bucks…you can kiss ’em!”

The offer itself is a wonderfully dumb surprise, of course. It’s “Take my wife—please” with a pricetag. His subsequent repeated elaboration that this amounts to “ten a kiss” implies that either there’s a cheaper option on the table, like going to Subway and getting the six-inch instead of the foot-long, or perhaps that you save if you buy in bulk off the individual price of $15 per breast. The whole thing somehow manages to be both salacious and childish, like if the graffiti on the wall provided a number for neither a fuck nor a Buick, but the opportunity to “check out my weiner.”

But as you might expect from an actor with Collins’s bonafides, it’s all in the delivery. His eyes shine with twinkle straight out of Looney Tunes. A wolfish grin borrowed from Tex Avery spreads across his broad sweaty face. His eyebrows move with exaggerated Groucho Marx mischief. After being relatively deliberate with tell you what and for twenty bucks, he whips through you can kiss ’em in a pair of rapid up-and-down inflections, like if he says it fast and forcefully enough it can be fired directly into the brain of his mark, so he’ll think it was his own idea.

I make a lot of hay out of a lot of minor Road House moments, because they often communicate much more than intended. That isn’t the case here. This is a minor Road House moment that does exactly what the expert performer behind it set out to do, no more and no less. He wanted to seem funny, horny, eager, slightly stupid, and wholesomely sleazy. Unlike he perpetually failing Cobra Commander, he got what he wanted.

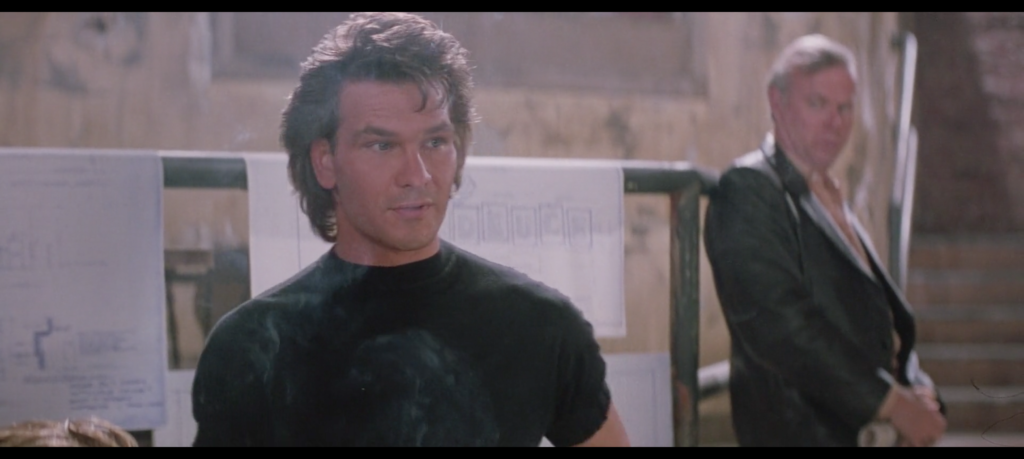

043. Good times with good friends

February 12, 2019Part Two of “The Agreement,” a special Valentine’s Week series

These two fellows are out for a night on the town, and their evening has brought them to the Double Deuce. There they can enjoy the musical stylings of the Jeff Healey Band, watch a shirtless man dance, interact with such luminaries as the Laughing Man and Mr. Clean, watch two brothers fight each other until they’re rolling on the ground near the pool table, potentially get beaten up by a bouncer with anger management issues, buy drugs from a waitress, throw beer bottles at a chickenwire fence, watch a bouncer pick up underage girls, buy a Buick—the world is truly their oyster. They’re sharing a drink they call Miller Genuine Draft, but it’s better than drinking alone.

And what a pair a’ attitudes they are! Our friend on the left, known to posterity as Gawker (actor Michael Wise), has the glee-squinted eyes and three-mile smile of a guy whose inebriation has enhanced his personal sense of good fortune tremendously. As well it might! He’s being inveigled to observe the excellent breasts of the Well-Endowed Wife by her Sharing Husband, an invitation he has gratefully accepted. “Fine, ain’t they?” Sharing Husband asks rhetorically; look at Gawker’s face and see if you can guess the answer.

His unnamed and uncredited pal is a delight as well. With bright eyes and bushy brows that both a) make him look like the wacky horny best friend in any number of ’80s sex comedies and ’90s Skinemax flicks, and b) appear as if they got spooked by Gawker’s smile and migrated to the next face over to avoid the space crunch, he plays a similar role in relation to his gawking friend that SH plays to WEW. He is there to beam approval, to offer encouragement, to generally egg things on. He too is clearly tickled pink by Well-Endowed Wife’s namesakes, but his gaze is reserved as much for Gawker as it is for her. He wants to see his friend seeing the thing they’re both seeing.

This is more common in Road House than you might think. In this film, it is often not enough to experience events on one’s own. An audience is required to confirm that the thing that has happened really has happened. It makes sense given the subject matter. When you’re a famous cooler hired to clean up an absolute cesspool of a nightclub, it won’t do to bust a few heads anonymously. The word needs to get out, to both the nice people and the ne’er-do-wells, that things have changed. By the same token the bad guys need their fellow goons’ laughter and howls of approval to make them feel their actions are justified, and they need not just their direct victims but everyone else to see what happens when they are defied. By the back end of the film Brad Welsey’s terroristic attacks on businesses who resist his protection racket take place for virtually no other purpose.

Gawker and friend aren’t keeping each other in a fashion anywhere near that brutal. But as we asked yesterday regarding Well-Endowed Wife and Sharing Husband, would the events that are about to unfold have taken place if Gawker had gone to the Double Deuce solo that night? Or is the presence of a friend, to exchange knowing glances and exclamations of pleasure, to verify and reify the spectacle, required to fully enjoy that spectacle? And is that not unlike the act of watching Road House itself?

042. Attitudes

February 11, 2019Part One of “The Agreement,” a special Valentine’s Week series

“Ever seen a better pair a’ attitudes?”

Even for a film that has already introduced us to “dirtball” and “moose-lips” (though “chicken-dick” is still a ways away), Road House still enters uncharted linguistic territory with the euphemism the person on the left of the above photo uses for the breasts of the person on the right. This is of course the right, perhaps even the calling, of screenwriters David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin. If your goal is to make an audience that is quite possibly already inured to chuckleheaded idiocy sit up and take notice when a large, sweat-soaked gentleman, whose first line of dialogue is the kind of guffaw you’d write out as “HAW HAW HAW HAW HAW!” like he’s Pete from the old Mickey Mouse cartoons, proudly displays the body of his special lady for particularly besotted onlooker…I mean, admittedly the bulk of the work has already been done for you. Still, in a language with more slang terms for tits than tits themselves, “attitudes” doesn’t hurt.

Our new friends, billed in the credits as Sharing Husband (Christopher Collins, no relation) and Well-Endowed Wife (Cheryl Baker) may have hit on something more than skin deep with this coinage, however. One look in the eyes of Well-Endowed Wife will tell you that her attitude is, indeed, half the fun of engaging with her in a bit of shitface-drunk barroom repartee. It’s in the way she smiles, twirls her hair, angles her body toward the audience, and on and on. As we’ve said before, arousal is lovely, desire is lovely, and by that standard Well-Endowed Wife is lovely. It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing, and to borrow the words of a great man, Well-Endowed Wife is swingin’ on the front porch, swingin’ on the lawn, swingin’ where she wants cuz there’s nobody home.

But the use of “pair” is unintentionally revealing. (That’s the last time you’ll hear that phrase used to describe this scene.) The joy on Sharing Husband’s face and in his voice as he proudly draws attention to Well-Endowed Wife’s unabashed sexual self-confidence is unreconstructed and pure and palpable. (Not as palpable as some other things in this scene, but still.) Without his Wife’s endowments, Sharing Husband would have nothing to share. She’s the reason he is who he is, in a sense so literal it scrolls up the screen in black and white at the end of the movie.

And now we come to the heart of the matter. Would either of them look like this, act like this, feel like this without the other across that table? For while her happiness clearly fuels his, we may conclude from their conduct, and from the words chosen to describe the situation, that the reverse is also true. Just as Sharing Husband requires the endowments of his Wife to thrive, Well-Endowed Wife relies on her husband to share those endowments to maximal erotic effect. To give the complexities of cuckoldry, polyamory, and swinging as thorough an examination as they deserve would distract us from walking the Dalton Path. But while there are certainly varieties of each in which the presence of both partners is not necessary to achieve the desired sexual frisson, that does not appear to be the dynamic in play here. They exist in tandem, and it is in tandem that they must be observed. They take that sawdust-strew stage together.

Sadly, they are given reason to reconsider the particulars of their arrangement by scene’s end, in this respect and many others. For now, though? The whole is greater than the sum of Sharing Husband and Well-Endowed Wife. They are pandrogyne, the two-in-one. Ever seen a better pair a’ attitudes? Can’t say that I have, sir. Can’t say that I have.

041. Breaking a table with a human face

February 10, 2019If you want a picture of the Double Deuce, imagine a table broken by a human face — for ever. I’ve been thinking about the way Dalton grabs the Hawaiian Shirt Knife Nerd who was willing to defend his girlfriend’s right to dance on a table literally to the death by the back of his head and smashes his face down into a second table so hard and so fast that the wood splinters cleanly in half a lot lately. It’s a terrifically intuitive and forceful bit of fight choreography, that certainly helps. It conveys Dalton’s efficiency of movement and his power at short range, key to making him seem like a physical threat when half the characters in the movie say “I thought you’d be bigger” to him at one point or another.

Crisp editing by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link (Die Hard, RoboCop, Predator, Commando, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Tombstone) sells the move, but not alone. As an actor, Patrick Swayze takes a heretofore unprecedented turn for the savage in this moment, scowling with fury we’d previously seen no trace of at all. As time passes we’ll see more and more of this look from him. (To the extent Dalton has a character arc it’s largely one long descent that begins at a moment we’ll discuss in detail later in this series and ends with five murders.) Dalton traffics primarily in a blend of the Western and Eastern forms of coolness; he’s gunslinger tough and martial-artsist enlightened. The audience needs to see what happens when he gets heated up, and how little normal men can do to stop him when it happens.

When does it happen? This is important as well. The scene that precedes the table incident is none other than the Giving of the Rules, in which Dalton lays out his credo for successful bouncing and cooling. “Never underestimate your opponent/expect the unexpected”? Check. Dalton chose to act in such a way that this guy was done before he even realized the fight had started. No surprises coming from that corner. “Take it outside/Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary”? Okay, sure, we’ll allow it. This bizarre little man drew a knife and threatened to murder a bouncer simply because he’d been asked to ask his girlfriend to stop climbing on the furniture. Sounds absolutely necessary to me. (And the Third Rule? Perhaps you know it already, perhaps you don’t. We will not be discussing it just yet. We will not discuss it…until it’s time to not not discuss it. Let’s just say that grabbing a human being by his hair and forcing his skull through a table sturdy enough to dance on speaks volumes on the Third Rule’s contents.)

What happens immediately afterwards? Everyone in the bar gazes and gasps in awe. People nearly move in slow motion, they’re so stunned by his prowess. Even the woman whose boyfriend has just been given some kind of concussion gingerly takes Dalton’s hand to be led down off the dancing table, and looks back over her shoulder at him on her way out of the bar. This is a man worth turning into a pillar of salt for. “The name…is Dalton,” Cody announces from the stage (through the chickenwire), after being filled in by his sighted bassist as to the nature of the hubbub—like a talk-show host announcing a guest, or the lead singer introducing the band. People in the Road House Universe absolutely adore people who break tables with other people’s faces.

Finally, there’s the savagery of the act itself. Powerful agent to the uninitiated. WA-BAM! He broke a table with a guy’s face! Didn’t even give him a chance! If you’re a first-timer and you reach this moment, any fears you may have had as to whether the first big barfight was the last time you’d see anything that gratuitously, moronically violent, this lays your fears to rest. You ain’t seen nothing yet.

039. Biker Gang

February 8, 2019The very first people to give Dalton shit upon his arrival in Jasper aren’t Brad Wesley and his goons. They aren’t the corrupt members of the Double Deuce’s staff. They aren’t even Knife Nerds or other random ne’er-do-wells among the club’s clientele. They’re a biker gang, in the Double Deuce’s parking lot. “Mer-SAY-dees!” they whoop it up as Dalton parks his luxury work of German engineering in the unpaved unloading zone for the town’s worst element, glaring at him all the while. “Hey hotshot! What’s wrong with Dee-troit cars?” Dalton simply stares back at them and their bikes and their very cool ’80s bad-guy car, tosses away his cigarette, and goes about his business. You and I are left with more to ponder.

At first blush it’s just a bit of color, a way to convey that the Double Deuce is a rough and tumble environment before you so much as step through the doors, in the same way that watching Morgan the evil bouncer toss a guy through those doors a few seconds later (“Don’t come back, peckerhead!”) lets you know what you’re in for once you set foot inside. What makes it a uniquely Road House bit of color how none of it has the slightest relevance at any point in the future, and how no element of it is ever heard from again.

Are biker gangs a threat Dalton will face in his quest to clean up the Double Deuce, and eventually the entire town of Jasper? No. Not even a little bit, in fact. The problems all stem from Brad Wesley, the Fotomat King, and his merry band of assholes. This is Road House, not The Road Warrior. Though Dalton and Brad Wesley could well be the Mad Max and Lord Humungus of the post-guzzoline Missouri wastelands should it come to that, this is merely informed speculation.

Is there a slobs vs. snobs angle to the movie? Again, no. For one thing Dalton always stows away his fancy car and uses a ringer instead once he starts working, so he doesn’t even bring the Mercedes back to the Double Deuce, or anywhere else for that matter, until the end of the film. He doesn’t ostentatiously spend his money, or wow the local yokels with his citified ways, or even crow about his NYU philosophy degree to woo Dr. Elizabeth Clay. What’s wrong with Dee-troit cars? Nothing, as far as he’s concerned. (This is a question better directed at Brad Wesley.)

Maybe these guys play a role in the ensuing all-hands-on-deck barfight, the movie’s first? Once again, no. The instigators and all the primary combatants are just the usual drunken shitbirds and meatheads. While it is true that one of the bikers miraculously appears inside as the Shirtless Man about twenty seconds later, this is down to Road House‘s charmingly free-form approach to continuity, rather than the idea that this guy somehow raced around to a back entrance, bared his chest, and started boogying down in the time it took Dalton to cross the parking lot and enter from the front. The Shirtless Man, at any rate, is a dancer, not a fighter.

But in their own pointless way, the bikers illustrate the importance of Dalton’s First Rule: “Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected.” Your enemies could look like anyone, come from anywhere, and attack at any time, even if their offense consists solely of “Buy American” jingoism. A cooler of Dalton’s experience and skill would have devised a plan for combatting these creeps within seconds, and likely kept it filed away throughout the course of the film, in case Brad Wesley ever hired them to run his clunker off the road, or prevent him from accessing one of Jasper’s many auto and auto-parts dealerships—or, less facetiously, bring the fight to grizzled old road dog Wade Garrett before he so much as parks his motorcycle. Indeed, one could argue that Dalton’s purchase of a beat-up car to replace his Mercedes was his way of defeating these opponents by depriving them of their casus belli. Victory is his before battle is joined.

038. The Laughing Man

February 7, 2019The men who look at Dalton are not the only Road House characters who model behavior for their audience. Nor are the women. To understand this movie, one must understand the Laughing Man.

An anomalously odd, almost Lynchian presence in a film that’s otherwise much more straight-down-the-middle in its abject stupidity, the Laughing Man is an avatar for the audience in that the events of the film transmogrify him from observer to participant.

A member of the rogues gallery that greets Dalton upon his arrival at the Double Deuce, he is at first content to simply watch the opening barfight unfold, giggling and guffawing and going slightly crosseyed like a cartoon woodpecker all the while. As a matter of fact, he is at second content to do so, and at third, and presumably ad infinitum. In an another world, perhaps one in which Wes Bradley successfully wooed the first Dillard’s to Casper, Wyoming, this hyena-man is still standing by the bar, laughing like a Joker henchman at everything that has since unfolded. The fool on the hill sees the goons going down.

But that is not the world we inhabit.

In this world, the ageless waitress who appears to have started working at the Double Deuce after quitting her job at Norma Jennings’s Double R lobs a bottle through the air, intending to hit some other asshole but clocking this harmless nimrod right between the eyes instead. He goes down with the kind of exaggerated overselling you see from pro-wrestling mid-carders, or from anthropomorphic animals around whose heads birds chirp in a saturnine orbit after someone hits them with a rolling pin.

The waitress looks upon her works and despairs. But should we? No! The Laughing Man is concussed so that we might continue. He shows us that no matter how much we might wish to laugh at this movie, it will draw us in until we have no choice but to laugh with it, or suffer for our refusal. You are in the Jasper of the mind now. Laugh and the world laughs with you!

037. Denise & Carrie Ann

February 6, 2019I was a theater kid in high school, and yes, I am glad you were sitting down. As the president of the Drama Club, the only coed activity my all-boys Catholic high school had to offer, I usually had better things to do than nitpick blocking, from learning my own steps to realizing how unforgiving for teenage boys pleated dress pants can be. But I did have one pet peeve I remember to this day.

Pretty much every musical in the high-school repertoire has around three or four major characters who—whether because they’re too old, too young, don’t sing, don’t dance, aren’t residents of the town/actors in the company/members of the Conrad Birdie fanclub, or any number of other factors—don’t take part in the big dance numbers, or aren’t active in the events of a particular show case scene. However, they are often at least present at those times, typically clustered in little groups around the perimeter. What would always bug me was when two characters who’d never spoken to each other before in the show, and for whom because of narrative economy it would be a big deal for them to speak to each other, like worthy of a song and dance of their own, wound up standing next to each other, stage-whispering about Professor Harold Hill’s latest chicanery or whatever.

I think about that when I watch Denise, Brad Wesley’s kept woman, and Carrie Ann, the Double Deuce’s coolest employee, team up during the first big fight. They cower together to shelter from the action. They root and heckle and holler as a unit. They wrap protective arms around one another when the going gets tough. Denise cheers Carrie Ann on when she starts slugging one of the participants. She actually hands her a bottle to use as a weapon!

Do these characters have anything in common? Do they have any mutual friends? Do they ever speak to each other…I was gonna say again, but really the phrase I’m looking for is at all? Do they even come within five feet of one another? If you’ve read thirty-six essays about Road House and counting you’re no doubt familiar enough with the film’s approach to continuity to answer those questions. But there’s a gigantic fight scene going on, and they’ve gotta stand somewhere, and the director is probably too busy telling gigantic men which tables to fall through, so a few perfunctory “stand over there”s are all they got, and they improvised. If it helps, imagine they’re the juniors playing Mayor Shinn and Mrs. Paroo, silently emoting together while forgetting to cheat toward the audience during “Shipoopi.”

036. Bleeder

February 5, 2019I want to tell you a story of a man and his bleeder.

The man is Brad Wesley—sportsman, outdoorsman, liquor distributor, civic leader, JC Penney franchisee. The bleeder is O’Connor, the goon upon whom Brad Welsey’s disfavor falls, to his great misfortune.

The scene in which Wesley beats O’Connor, ostensibly for failing to defeat his newfound enemy Dalton and restore his nephew Pat McGurn to his position as bartender at the Double Deuce but for the stated reason that O’Connor bleeds too much (?????????), is a fanmaker. It’s up there with the first deck-clearing barfight, the realization that Dalton visits four separate salesmen of cars and/or car parts, the Giving of the Rules, Doc’s Dress from an Italian Restaurant, “pain don’t hurt,” you name it. It’s even more of a fanmaker if you are, as you should be when you watch Road House, fucked up. It whipsaws back and forth from one emotion to its diametric opposite so fast and so often that it makes you feel fucked up whether you are or not. Only the lag time in comprehension caused by chemical intoxication comes close to replicating the Bleeder Scene’s otherwise inimitable psychological Gravitron.

We’re going to take it frame by frame.

The goons roll up to Brad Wesley’s mansion. Among them are Pat McGurn, Tinker, and O’Connor, the three men defeated by Dalton and his bouncers at the Double Deuce the previous night. Ketchum and Karpis, who are never referred to by name in the film, arrive separately in the monster truck.

Wesley and his right-hand man Jimmy exit his mansion to greet their visitors. Wesley is holding a half-smoked cigar. Jimmy puts on his shades. Wesley sighs with exasperation. Wordlessly and shamefacedly, Pat skulks past them into the mansion himself.

Wesley smiles sardonically.

[Tone: disapproving irony]

WESLEY: Did I explain it wrong? Is that it?

O’CONNOR: No boss, you didn’t.

[Tone: pity for Pat, with a hint of condescension]

WESLEY: Pat’s got a weak constitution. You boys know that. That’s why he’s working as a bartender.

[Tone: righteous familial fealty]

He’s my only sister’s son. And if he doesn’t have me, who’s he got?

[Tone: just the facts about the job]

And If I’m not there, you’re there.

Wesley affectionately grabs Jimmy by the back of the neck.

[Tone: mixed admiration for his favorite son and regret for his own lack of perspicacity]

Shoulda let you go, Jimmy.

Wesley begins circling the assembled goons.

[Tone: Disappointed schoolmarm]

Well, one of you boys owes me an apology. Now I’ll leave it up to you to decide which one of you wants to say “I’m sorry.”

TINKER (contritely removing trucker hat): ’m sorry, boss.

O’CONNOR: I’m sorry, boss.

[Tone: forgiving father figure]

WESLEY: I believe you, Tinker.

[Tone: mounting suspicion]

But you, O’Connor, somehow I don’t believe you.

[Tone: assistant manager who really doesn’t want to have to report this to corporate]

Now you better try it again, because if there’s one thing I can’t stand, it’s a man who’s untruthful.

O’CONNOR: I’m sorry, boss.

[Tone: fast-burning anger]

WESLEY: And if there’s one thing that disgusts me, it’s a man who can’t admit when he’s wrong.

O’CONNOR: I swear to God, boss, I’m sorry.

[Tone: pure hate]

WESLEY: You disgust me, O’Connor. You wanna know why you disgust me?

O’CONNOR: No, why, boss?

Wesley punches O’Connor in the face, causing his nose to bleed. O’Connor feels the blood and looks at his boss, confused.

[Tone: cheerful scientific observation]

WESLEY: ’Cuz you’re a bleeder. You bleed too much.

[Tone: the kind of contempt that ends with kneeing someone in the balls]

You are a messy bleeder.

Wesley knees O’Connor in the balls. O’Connor doubles over.

[Tone: pure disappointment]

You’re weak.

[Tone: prepping for a Quod Erat Demonstrandum]

You got no endurance for pain.

On “pain,” Wesley slams his fist down onto the back of O’Connor’s head, knocking him to the ground.

Wesley looks at the other goons, who are all smiling happily at the unfolding events, with “what did I tell you” grin that rapidly fades. He pats the crumpled O’Connor on the back.

[Tone: stern but ultimately kind tough-love football coach]

Now come on. Get up.

[Tone: ER doctor on a double shift talking to a drunk patient who cut his forehead after walking into a lamppost]

Yeah you’ll be fine. Come on.

O’Connor tries to stand and falls even flatter. Wesley looks around at his goons.

[Tone: “Do I have to do everything around here?”–style fed-up fury]

Well help him up!

Ketchum and Jimmy lift the dazed O’Connor to his feet.

[Tone: enough with the pity party]

You’re gonna be fine.

Wesley smiles benevolently. He puts his hand on O’Connor’s shoulder.

[Tone: “I’m not just your boss. I consider us a family.”]

And you know why? Because I like you.

O’Connor smiles, glad to be forgiven. Wesley socks O’Connor right in the jaw, knocking him out cold. Wesley addresses his goons as he turns to go back inside.

[Tone: scraping cat turds off his shoe]

Get this piece of shit coward outta here.

The Bleeder Speech contains every feeling possible to express in its idiom. It is the White Album of ‘80s action-movie bad guy speeches. Brad Wesley is the Fab Four (and Eric Clapton on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps”), and the Bleeder is his muse—the Beach Boys, Bob Dylan, John Lennon’s mom, Paul McCartney’s dog, Yoko Ono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Ringo Starr quitting and fleeing to a boat in Sardinia for a few weeks, and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi all rolled into one, wrapped in a short-sleeved dress shirt, and beaten up in a driveway with a monster truck parked in it.

035. Shithead

February 4, 2019I don’t think I’m spoiling anything for you when I say things do not go well for O’Connor, as a rule. The Brad Wesley goon most likely to be mistaken for a once-promising Celtics prospect who suffered a career-ending injury and now owns a chain of Honda dealerships throughout the Greater Boston area, O’Connor gets his ass definitively kicked by Dalton and his fellow bouncers within minutes of our meeting him. He gets it kicked again by Brad Wesley, basically for the crime of getting it kicked in the first place, though the proximate cause is his pronounced tendency to bleed from ass-kickings, a condition Wesley is not helping. He gets it kicked again by Dalton and Wade Garrett later in the movie, gets it kicked right into the trash, I’m not even kidding, he ends up in a dumpster. And in the end Dalton murders him off-screen. Thus always to bleeders.

But this towering yahoo sure makes an impression when he first shows up on screen thanks to four simple words: “Hey, shut up, shithead.”

Does he say this to Frank Tilghman, who’s office he’s crashed in order to force him to re-hire Wesley’s sister-son Pat McGurn? Does he say it to Dalton, who shows up and tries to put a stop to it all? Does he even say it to Pat himself, a guy who needs his Rich Uncle Pennybags to make people be nice to him? No. He says it to Tinker, the sweatiest goon, cutting off Tinker’s attempt to engage in biting repartee with Dalton.

PAT: You don’t get it, do you?

DALTON: Why don’t you explain it to me.

TINKER: I’ll explain it to you—

O’CONNOR: Hey, shut up, shithead.

Mere transcription doesn’t do O’Connor’s delivery justice, though. For one thing, it necessitates the use of commas, which are not audible in actor Michael Rider’s Juilliard-educated bass voice at all. The whole thing comes out in a single exhalation, heyshutupshithead, like one self-contained sound of rebuke is all Tinker merits. O’Connor looks and sounds bored with even having to go through that much effort before he so much as finishes the sentence.

“Utter contempt” is too generous to describe what’s going on here. The fact that O’Connor sounds like White Barry White makes it all the more brutal, more hilariously unnecessarily mean. This is the verbal equivalent of missing the trash with the thrown remnants of a half-eaten egg salad sandwich and just leaving it there as you walk away. It’s the voice of God doing Pusha T’s “EEYUGGH” ad lib, at you. Never before or since have two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response more effectively.

034. Thru the Eyes of Tilghman

February 3, 2019It goes ill with the Double Deuce. Frank Tilghman colorfully describes it to Dalton upon their first meeting as “the kind of place where they sweep up the eyeballs after closing,” and other than the lack of actual traumatic globe avulsions nothing we witness when we arrive contradicts this. It’s a hellhole. The bartender is a nepotism hire who robs the joint blind. The band gets pelted with bottles when they take five in order to urinate. The chief bouncer starts fights. Another bouncer fucks teenage girls in the supply closet. A waitress sells coke in the bathroom (presumably interfering with those customers who wish to snort coke in the bathroom, as is custom in classier establishments). Bottles, glassware, and furniture get smashed as regularly and thoroughly as the customers do. The owner is forced to waste precious man-hours bowdlerizing graffiti.

This much we know—now, anyway. But during the opening sequence, prior to our first visit to the Double Deuce, prior even to Tilghman’s description of the place to Dalton, we don’t know any of this unless we have watched the entire film before. That opening sequence, which depicts Frank Tilghman’s journey through the capacity crowd at the massively popular Bandstand where Dalton works at the time, is one of the reasons Road House rewards repeat viewings: Only people who’ve already witnessed the nightmare that is the pre-Dalton Double Deuce can understand what the hell Tilghman is doing.

In short order, Frank Tilghman marvels at…

- a handrail

- a bartender pouring shots

- a cash register ringing up a sale

- a waitress carrying a tray of drinks

- a man lighting a cigarette for an attractively dressed woman

- a credit-card transaction

- a man leaving a large cash tip

- a bar band

Remember, and this is key: Frank Tilghman owns a bar.

If you think I’m kidding about Tilghman “marveling at” these things, watch actor Kevin Tighe’s eyeline as he looks at each of these things in turn, whether within frame or via match cuts to the actions and objects in question. Then look at his face afterwards. He’s impressed. Thoroughly so. He takes it all in so intently that he reads like a villain casing the joint. Granted, he reads like that all the time, but as we’ve established, nothing that happens during the opening happens by accident.

You wanna know how bad things have gotten at the Double Deuce? Frank Tilghman, who owns a bar, looks at the basic components of literally any bar on earth like the apes look at the monolith in 2001. Forget the eyeballs on the floor. Just follow the eyeballs in Tilghman’s head.

032. Sh-Boom

February 1, 2019Originally recorded by doo-wop group the Chords, who charted with it in 1954, “Sh-Boom” became part of the pop-culture firmament largely because of a cover version by the Crew Cuts that was also a hit later that year. Both versions are the kind of gleeful pure-dee nonsense that make doo-wop such a fun genre to pronounce, let alone listen to. While Chords’ rendition has a jaunty swing to it, the Crew Cuts’ whitebread revamp emphasizes the gliding, carefree, “life could be a dream” side of the song. It sounds like a Sunday drive.

Of course, most people content themselves with driving on the right side of the road, Sunday or any other day, whether they’re listening to “Sh-Boom” or “Yakety Yak” or “Symphony of Destruction” by Megadeth. This is not just because it’s the law, or because it’s much safer not to drive into oncoming traffic. It’s because staying in your lane allows you to chart a long straight course, and a long straight road is the most fun kind to drive. The Germans modeled a whole genre of music after it and everything.

When we see Brad Wesley driving his red convertible (a Ford, possibly ill-gotten from Strodenmire’s ill-fated Ford dealership) with the top down on a bright sunny day, the fact that he’s singing “Sh-Boom” fits. It’s that kind of song. Wesley is also swerving from one side of the road to the other and back, over and over, like a sine wave, like a snake. This, too, fits. He’s that kind of person. But the actual driving process deserves closer examination.

Until Dalton passes by headed in the other direction, nearly getting run off the road in the process, there isn’t another car in sight. Wesley has the road all to himself. He could comfortably cruise along, taking in the air and the scenery. He could floor it if he felt the need for speed. (“He’s go the sheriff and the whole police force in his pocket,” Red Webster tells Dalton later in the film; the line is likely intended to explain why crimefighting in Jasper is entirely the province of bouncers, but it explains a lot of other things too.) This is what normal people who enjoy a nice drive would do.

As anyone who’s whipped around an empty high-school parking lot could tell you, rocking the steering wheel back and forth like Wesley does creates a push-pull swerving sensation that’s much more enjoyable in theory than in practice. If you’re a 17 year old looking for a quick thrill when you’re all out of kratom or whatever, sure knock yourself out. But to drive that way over a significant distance is less fun than just driving straight, not more.

Ben Gazzara sells the nauseating joyride as well as you’d expect from an actor who, prior to Road House, created the role of Brick in Cat in a Hot Tin Roof by Tennessee Williams. And indeed we can take Wesley’s glee as entirely sincere, but not because he’s having fun driving in and of itself. He has gone out of his way to make his drive less physically enjoyable, because the thrill of being a gigantic asshole and recklessly endangering the lives of others more than compensates for the loss.

This is the kind of man Brad Wesley is. He can hey-nonny-ding-dong-alang-alang-alang his way back and forth across every inch of asphalt in Jasper and none can say him nay. That’s worth a crick in the neck.

031. The First Rule

January 31, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This is the first.

1. Never underestimate your opponent. Expect the unexpected.

To the uninitiated, Rule One sounds like it ought to be Rules One and Two. The first part dictates that one cannot take victory for granted no matter the look of the foe, wisdom borne out time and time again throughout the film. Old men prove to be exceptionally capable fighters. Heavy men move at speeds men half their size can’t match. And as the Knife Nerds amply demonstrate, even the most rat-faced and weaselly goons can carry death in their denim. You underestimate these men at your peril. Assume anyone you face in open combat, even the bleeders and the sister-sons, can and will kill you if given the chance.

Expecting the unexpected is a different matter, or so it seems at first glance. Sometimes that means anticipating that a would-be assassin has a boot-mounted knife, or that a business dispute will be settled with a monster truck, certainly. But the unexpected could also be advantageous, could it not?

Not for the purposes of Rule One, no. The combination of these two diktats is not arbitrary. By wedding the latter to the former, Dalton suggests that the unexpected always breaks in favor of your opponent: a bootblade stabbing at a human face, for ever. The bouncer must accept this.

But the inverse is also true. If never underestimating your opponent necessarily and coterminously entails expecting the unexpected, it follows that a rational assessment of your allies deems them perfectly reliable. You don’t need to wonder whether your fellow bouncers can help you. You can bank on it. They will never disadvantage you in unexpected ways like your enemies might. Your comrades will be there and be true. You can expect it. “Watch my back and each others’,” Dalton says near the conclusion of the Giving of the Rules. But with the First Rule, he’s said it already.

It’s a bit of an “If you think this sentence is confusing, change one pig” situation, isn’t it: For bouncers to be perfected, they must follow Dalton’s three simple rules, the first of which takes their preexisting perfection for granted. But simply by turning the First Rule around in their minds the bouncers of the Double Deuce are that much further along the Dalton Path. They begin thinking every enemy with the wary respect you show a large animal or an operating piece of heavy machinery. They envision scenarios that will surprise and shock them, and thus begin to take those surprises and shocks in stride. In so doing they become people who are unsurprising, consistent, dependable, stalwart—each man a hidden blade in the boot that is the bouncer corps, expertly wielded by the cooler’s outstretched leg, working in concert against all the goons that were or are or will be.

030. “My only sister’s son”

January 30, 2019“I name Éomer my sister-son to be my heir.”—Théoden, The Lord of the Rings

“He’s my only sister’s son, and if he doesn’t have me, who’s he got?”—Brad Wesley, Road House

Not even I, a person with the White Tree of Gondor tattooed on my arm who is writing an essay about Road House every day for a year, can come up with much of a connection between the King of Rohan and the Chief Job Creator of Jasper, Missouri beyond the antiquated syntax with which they refer to their nephews, Éomer son of Éomund and Pat McGurn respectively. Wesley isn’t about to name his mustachioed kinsman his successor anytime soon, certainly. “Pat’s got a weak constitution, you boys know that,” he tells his assembled henchmen after two of their number, Tinker and O’Connor, failed to forcibly reinstate Pat in his old gig at the Double Deuce during one of the Knife Nerd incidents. “That’s why he’s working as a bartender.” Poor Pat, not even fit for full-time goonmanship.

Pat isn’t even present to hear this condescension, having slunk shamefacedly into Uncle Brad’s mansion at the first opportunity, allowing his comrades-in-goon to take the heat. Why should he bother sticking around? He knows his place, and it’s not at his uncle’s side. It’s Jimmy, Wesley’s strong right hand and, in my considered opinion, secret bastard son who’s the heir apparent. “I should have let you go, Jimmy,” Wesley says regarding the failed mission, an avuncular (fatherly?) hand on the back of the younger man’s neck. Better for Pat to spare himself the sight.

So no, Wesley’s rhetorical style here doesn’t remind me of Théoden King. Rather, I’m put in mind of another great man.

Jack Lipnick is the head of Capitol Pictures, the studio that hires a certain New York playwright to give a Wallace Beery wrestling picture That Barton Fink Feeling. Like Brad Wesley, he came up the hard way (“I mean, I’m from New York myself. Well, Minsk, if you wanna go all the way back—which we won’t, if you don’t mind, and I ain’t asking”) and rose to prominence and power by exerting control over the local economy, largely by screwing other business owners out of their share (regarding his assistant Lou Breeze: “Used to have shares in the company. Ownership interest. Got bought out in the Twenties. Muscled out, according to some. Hell, according to me”).

The tone Lipnick adopts when speaking about producer Ben Geisler, whom he fires instead of Barton when the latter screws up, sounds familiar. “That man had a heart as big as the all outdoors, and you fucked him!” he says, voice soaring as if with the eagles as he describes the generosity of spirit found in a guy he shitcanned, then cracking like a whip as he drops the f-bomb on the person truly at fault, at least in his eyes.

Though he prefers physical assault to firings, Brad Wesley reacts in similar fashion over his sister-son’s plight, arbitrarily beating his goon O’Connor unconscious for, alternately, being untruthful, unable to admit he was wrong, weak, unable to tolerate pain, cowardly and above all prone to bleeding. O’Connor’s failure regarding Pat may have occasioned the beating, but it isn’t even mentioned during the beating itself as one of Wesley’s half-dozen reasons for inflicting it.

For men like Wesley and Lipnick, people are worth caring about only to the extent that doing so, or pretending to do so, enables them to torment others on their nominal behalf. These men, like their words, are overinflated and empty. The overwrought sentiment intended to conceal the lie reveals it instead.

029. Knife Nerds

January 29, 2019A person watching Road House from a remove of decades could be forgiven for wondering if packs of pointy-faced dorks with switchblades, roaming the land and stabbing bouncers, were the subject of some sort of ginned-up panic along the lines of Satanic nursery schools and wilding superpredators. No fewer than four blade-wielding wieners try to slice up Dalton before the film is even halfway over. Though as a category they are a distant second to brawlers in terms of goon prominence, they bear examination for what their presence tells us about Dalton’s world.

These two nitwits are the first people in the film to get bounced, from the Bandstand, before Tilghman hires Dalton away from the place to come work at the Double Deuce. The fellow on the right sparks a bounceable incident when he attempts to pay for the attentions of a young woman who finds the offer insulting and pins the hundred-dollar bill he offers her to the table with a knife; he knocks over her chair by planting a kick right between her legs and we’re off to the races. Dalton thinks he and his men have cooled things off, but this weaselly goof yanks the knife right back out of the table and takes a slice out of the cooler’s arm the moment his back is turned. He and his friend Farrah Fawcett are taken outside by Dalton and company, thinking they’re about to throw down with the man himself. (“I’ve always wanted to try you,” says the knife nerd to Dalton prior to exiting the premises. “I think I can take you.” This is another essay entirely.) But their date with immortality is cancelled when Dalton just turns around and goes back inside. They hurl invective at him in an effort to rile his temper or shame him into combat, but not even such vicious insults as “dirtball” and “moose-lips,” which are things these two people yell at the top of their lungs at a man they’re trying to intimidate, can change Dalton’s mind. Later, Dalton will caution the staff of the Double Deuce against taking such insults personally, since they’re just “two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response.” That knowledge is clearly hard-earned.

This beady-eyed Parrothead is the first person Dalton bounces from the Double Deuce, earning him the undying awe of the people there assembled. All he wants to do is watch his girlfriend dance on a table. Such a fan of her gyrations is he that he attempts to murder, with a knife, the bouncer who asks them to cut it out. “Motherfucker” is his preferred binominal, but what he lacks in creativity he makes up for in extremely loud shirts. Dalton breaks a table with his face, and thus the cooler’s head prevails.

Here’s our old friend Pat McGurn, Brad Wesley’s only sister’s son and the Double Deuce’s now-ex bartender. He’s returned with his fellow goons Tinker and O’Connor in tow to muscle Tilghman into rehiring him, lest Wesley shut down liquor distribution to the bar. When Dalton takes mild, even bemused issue with the idea, Pat whips out a monstrosity that looks like something Legolas would pull out of an Uruk-Hai before lobbing it into another one’s forehead. As he attempts to stab Dalton in the fucking face in front of multiple witnesses in a crowded bar that can be observed clearly through the glass window of the office in which the murder attempt is taking place, he calls Dalton “chicken-dick.” In the end it works out no better for him than it did for Store Brand Crockett and White Tubbs or Hawaiian Punch, but I’m pleased to note that he at least came up with the film’s most ridiculous insult.

For the purposes of this essay I almost didn’t count Ketchum, the unnamed and fundamentally anonymous Brad Wesleyan who drives the monster truck and for whom bladed weapons are a specialty, as we will later learn to tragic effect. Though he is an obnoxious prig, he actually seems like someone you’d think twice about getting in a fight with. That ought to—ought to—elevate him out of Knife Nerd territory. On the other hand, his first knife attack involves attempting to high-kick Dalton in the head with a blade embedded in the toe of his cowboy boot, one of the lamest attempted murders in the movie, and it’s not like the competition isn’t stiff. Dalton catches his leg in midair, twists it savagely, and drags the guy out of the bar on his ass, which he proceeds to kick. Ketchum may look tough. He may even be tough. He doesn’t call Dalton “shit-ass” or “poodle-sack” or anything. But watch him dragged out to the curb like so much stonewashed garbage and then deny the Knife Nerd within at your peril.

All of these men use the blade as surrogate bravery. They may talk a good game—alright, they may talk a game. But when push comes to shove, they attempt to stab. They can whip out whatever they want in their attempt to try and take Dalton. But Dalton’s blade is his body, honed to a nicety, and it will wind up inflicting a far more serious gash than any knife before the story is through. A true cooler is worth a hundred such cowards.

028. Lebowski (I): Windshields

January 28, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a grizzled gray-haired man with a molasses drawl played by Sam Elliott dispenses wisdom to a practitioner of tai chi who finds himself at odds with a rich, sleazy business magnate with a personal goon squad played by Ben Gazzara. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film about same.

We will be revisiting the Road House/Lebowski Cinematic Universe. Boy, will we! But for now let’s focus on what I like to call The Windshield Shots. In Road House, Wade Garrett has just arrived in Jasper, Missouri to lend a hand to his old running buddy Dalton as the latter wages an increasingly vicious war with Brad Wesley, the film’s Gazzara. After rescuing his ass from a four-on-one beatdown—seriously, they’re just holding him in place and punching him in the gut like he’s a human heavy bag when Wade finally shows up to save the day—Wade goes for a drive in the passenger seat of Dalton’s car, the abuse of which by the angry patrons of the Double Deuce is a running gag, one that runs too far by any reasonable standard in fact. For that reason, riding shotgun puts Wade in an unenviable position.

But look at Wade here. He’s tickled pink! I assume he likes the feel of the wind through his magnificent head of hair, but it’s more than that. We will see, time and time again, how his most dangerous and dirty exploits amuse him, and how the same is true of Dalton’s. Riding through Jasper with a gigantic hole of shattered glass in front of him reassures him that it’s business as usual for his treasured “mijo.” It’s a sign that Dalton’s pissing off all the right people. And since Wade is a firm believer in the cut-and-run strategy when shit gets too heavy, he’s no doubt aware that the car will not long outlive Dalton’s stay in town, however long that may be. “It seems to me you’d be a little more more…philosophical about it,” he says later (much later) that evening, about an entirely different matter. But that hole in the glass, framing his “Aw shit-hell kid, I’m in hog heaven” grin, is already our lens into the Wade Garrett Mindset. He looks at broken things and sees a chance to live a life defined more by parts than the whole they add up to. Moving from one sensation to the next, treating calamity as opportunity, riding the nightlanes, bound only to those who ride with him: That is Wade Garrett. All Dalton can do is grin and bear it. Currently, it is time to be nice.

The Lebowski triarchy is an entirely different matter. Put aside whatever this Windshield Shot does or doesn’t owe to its predecessor. (I certainly believe the Coen Brothers, who after all put Sam Elliott and Ben Gazzara in their movie about a pair of weirdos fending off some rich guys and some goons, had seen Road House, but it’s irrelevant.) Despite sharing the tonsorial sensibilities of Wade Garrett, the Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, is pointedly not enjoying this breezy night drive. There will be no next down for him to head to. His car is not something he can stand to sacrifice. The Dude does not abscond. The Dude abides. He’d prefer to abide with a windshield.

Walter Sobchak occupies the Wade position in the car, but again, the contrast is revealing. No smile for Walter, no “shyush, don’t this beat all” grin. Walter is a man who can never admit that things have not gone according to plan, that every eventuality has not been foreseen and warded against. If at the beginning of the evening he said they would swing by the In-N-Out Burger, then goddammit that’s what they’re doing. If, in the interim, they attempt to brace a teenage boy for money he didn’t steal, vandalize a car he didn’t buy, and antagonize the neighbor who is the real owner of the car until the Dude’s own vehicle winds up getting the worse of it…well, the In-N-Out’s still there, isn’t it? Then he’ll by god buy it and eat it. As he says elsewhere in the film, “I’m staying. I’m finishing my coffee. Enjoying my coffee.” Situation normal, et cetera et cetera. Ironically, only his fellow veteran of American imperialist adventure in East Asia, Brad Wesley, shares this need to control the narrative.

Oh, Donny? Donny’s literally taking a back seat, literally a few steps behind. (Windshield’s out, Dude.) Lacking any physical or intellectual agency, he’s just along for the ride. He has no character in Road House. Unless…unless…

027. Red

January 27, 2019DALTON: Dalton.

RED WEBSTER: Red Webster. How long you gonna be in town?

DALTON: Not very long.

RED WEBSTER: That’s what I said 25 years ago.

DALTON: Really? What happened?

RED WEBSTER: Oh, I got married. To an ugly woman. Don’t ever do that, it just takes the energy right outta ya! She left me though. Found somebody even uglier than she was. That’s life. Who can explain it.

This is a segment of the first conversation Dalton has with Red Webster, auto parts supplier and owner of the closest business establishment to the Double Deuce. When this exchange takes place, these men have known each other for exactly thirty seconds. Their only dialogue up to that point is about which parts of Dalton’s vandalized car need replacing, and whether he should put in a standing order due to the nature of his job or pay as he goes. Compare this interaction to the way Dalton speaks to the staff of the Double Deuce the night he arrives—spartan and only barely polysyllabic. Red, it seems safe to say, is an oversharer.

When Red starts the story of his failed marriage to his ugly wife, however, it’s not clear this is anything more than a take my wife please joke, “It just takes the energy right outta ya” being the punchline. But then he keeps going, in short little bursts that sound like Manic Street Preacher song titles from the Richey Edwards era:

she left me though

foundsomebodyevenuglierthanshewas

that’s life

whocanexplainit

And boy oh boy does it sound like he wants to keep going from there! Credit the naturalistic performance of actor Red West (yep), a former high school chum and entourage member of Elvis Presley’s; it sounds like he’s actually cleaning out his mental closet right in front of us.

Unfortunately the vicissitudes of capitalism demand that Red pause long enough to ring Dalton up. This gives the cooler a chance to reinsert himself into the conversation before Red can continue his bittersweet reminiscence. Seconds later Brad Wesley and his chief goon Jimmy pop in and the moment is gone. Yet I often think of what it might have been like had they never arrived, or had Dalton never piped up. How far down the Red Webster hole could we have fallen?

Oh, I got married. To an ugly woman. Don’t ever do that, it just takes the energy right outta ya! She left me though. Found somebody even uglier than she was. That’s life. Who can explain it. Went to a seminar once. Thought it’d sort me out. Est, they called it. Bee Ess, you ask me. Cost a pretty penny though. Had to sell the old place. Moved in with my stepdad. Hell of a man. Saved my mother from herself, I reckon. Daddy died at Anzio. Stepdad came into the picture a year later, think it was. Car salesman. Figure that’s where I got it from. Bum leg. Died in ’77. Boat accident. Hell of a thing. Seen that boat store cross the street? They’re the ones sold it to ‘im. Nearly went outta business. All that bad press. Settlement put my niece through med school. Brother never forgave me for it. Wanted her to go into the family business. Took over Momma’s apiary after the the cancer took her. Loved his little girl. Figured she’d follow in his footsteps. She had different ideas. People hate different ideas alright. Always do. Crazy ol’ world. Wound up sellin’ the bees anyways. ‘Llergic. Twenty-two years and not a sting. Tripped on a garden hose. Face first, right into the hive stack. Coma. Thought he’d lose the eye. Gotta wear one a’ them patches now. Looks like a pirate. Who’d’a thought. Car salesman, last I heard. Full circle I guess. Shame, though. First-rate dancer. Thought he’d go Broadway. “Red?” he says. “The dance never made nobody’s bread taste better.” Had a point. Always called it that, the dance. Fancy-like. Heard they’re bringin’ that Batman back. From the tee-vee. Gonna be a movie. Darker, they’re sayin’. Thought I’d read me one a’ his funnybooks. See what’s goin’ on. The Batman, they’re callin’ him now. Don’t that beat all. Drove up to St. Louis. Found one a them stores, sells nothin’ but funnybooks. Die-rect Market, they called it. Die-rect to who? Reminds me of that Home Box Office. Gotta be pig ignorant to want a box office in your home. People linin’ up, yellin’ at you when the picture’s sold out. Kids sneakin’ in. Cold at night. Thick glass. Got some good progr’ms though. Boxin’. Seen that Die Hard on there. Helluva film. California. Never been. Don’t know what to make a them Kids in the Hall. You seen ’em? Pythonesque. Nature a’ the format, you ask me. Anxiety a’ influence. Nothin’ for it. Five’ll get you ten that’s why I sell car parts and not the whole thing. Wanted to do things my way. Outta my stepdad’s shadow. They fuck you up, your mom and dad. May not mean to, but they do. Larkin. Poet. English fella. Ain’t half bad. Spent nine months in Cornwall once, ‘fore I met the wife. Thought it’d be educational. Learn them Celtic dialects. Did some fishing. Hated it. Boats. They they are again. Recurrin’ characters, you might say. Who’s the author. There’s the question. Can’t find no answer. Never been what you’d call a religious man. Couldn’t see the percentage in it. Master a’ my own destiny’s how I like it. Funny way a’ sayin’ it’s all my fault. There it is. Still. You blame yourself, stands to reason you can fix it too. Better’n believin’ it’s all random. Agency, causality. Free wlll. Love’s a neurochemical reaction? Over-reaction, in my book. But who’s to say. Could be it’s inexhaustible. Could be one a’ them zero-sum jobs. Give love here, gotta take it away from there. Wife thought so. ‘Bout yanked my heart out, ‘fore I saw the light. Blinded by the ugly I suppose. ‘Less I used to see clear, and it’s heartbreak what done for my way a’ seein’ things. Ain’t that a kick in the ass. Wonder what else I got wrong. Shaped by circumstance. Sum a’ your experiences. Nature, nurture. Either or. Can’t step outside a’ yourself. Didn’t need a seminar to teach me that. Times are I look in the mirror, can’t even recognize m’self. Who’s that old man? Still got all my hair, though. Red as ever. Caught hell in school for it. Carrot top. Tried tellin’ em the name didn’t have nothin’ to do with it. La Rouge. Momma’s maiden name. French Canadian. Way back anyways. Looked into it once. Microfiche. Didn’t get very far. Fine print. Need glasses. It’s like I said: Used to see clear. Just can’t bring m’self to do it. Proud a’ these eyes, always have been. Girls loved ’em. Baby blues, they said. Got me further’n anything else I had goin’ for m’self back then. Still remember that first time. Told Momma I was goin’ to the pictures. She was a picture alright. To a fault. Hair trigger. Over ‘fore it started. Recovered fast though. Kept at it for two hours. Next day neither a’ us was walkin’ right. Mm mm. She was a one. State senator now. Mail her a donation every cycle. Sends a thank you. Neither of us says anything about it. Figure we don’t need to. Said all we needed to say that night. More’n one way to tell someone how you feel. You gotta tell ’em, though. One way or the other. No point to it all otherwise. Connection. Long and the short of it. That’ll be $2.99 for the aerial.