Posts Tagged ‘Marvel’

Marvel Movie Catch-Up Thoughts

May 6, 2015In the last three days I watched the last four Marvel movies.

Thor: The Dark World (dir. Alan Taylor): Wafer-thin characters and worldbuilding offset by charismatic performances and cheeky action sequences. I don’t quite understand the white dwarf sexual gravity exerted by Tom Hiddleston on large segments of the audience, but he and Chris Hemsworth are clearly having a ball every minute they’re on set. Same with Kat Dennings and Stellan Skarsgard and even, in this one at least, Natalie Portman, who’s only ever been good in Closer (and I guess Leon) but is fun here.

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (dir. the Russo Brothers): Exciting, well-staged action from start to finish — very much the cinematic child of the Ed Brubaker run on the comics, where the characters felt solid and rooted in physics but operating at the absolute peak allowed, like they rolled a 20 for every saving throw. Not street level, super-street level, if that makes sense. Chris Evans is shockingly likeable in that role, which is hard for both him as an actor and that character if you’re a commie like me. I’ve never bought Johansson as Black Widow, but okay, fine. Mackie was fun as Falcon, Redford was Redfordian as the evil suit, and I liked the future Crossbones guy. A solid message regarding the out-of-control security apparatus, too, that wasn’t undermined by Black Widow’s “you need us” testimony at the end the way I’d been led to believe it was. Best of the lot.

Guardians of the Galaxy (dir. James Gunn): A decent enough tonal and design throwback to ‘80s/early ‘90s sci-fi/action/popcorn fare — the Kyln prison looked like something out of Total Recall — but it overshot fun and hit shrill time and again. The fight scenes were poor, like a sort of warped version of the Captain America ones: All of these characters are way powered up, yet the nature of the story required them to be brawlers, so you were left with this down-and dirty fight choreography that just revealed how phony the physical effects were. And none of these lovable losers were as lovable as the film needed them to be, or clearly thought they were. How about that Chris Bautista though, huh? Funny stuff. Though that reminds me: Over and over again, the Marvel movies go to the most generic-looking blue-skinned-cosmic-type villains in the whole Marvel Universe. Laufey, the Frost Giants, Malekith, Kurse, the Dark Elves, Ronan, the Sakaarans, the Chitauri — it’s like they took their pointers from Guillermo Del Toro’s still-baffling decision to boil the entire Mike Mignola bestiary down to a shitty redesign of the frog monsters for Hellboy.

Avengers: Age of Ultron (dir. Joss Whedon): Nowhere near as confusing as advertised. Nowhere near as sociopolitically noxious, either; jesus, if ever there were an illustration of my Golden Rule of Internet Argument — interpret with minimum good faith, attack with maximum rhetorical force — it’s the litany of charges leveled against this relatively innocuous film, that’s for fucking sure. Whedon’s an awful director of action, you can never tell what the physical stakes are for any particular move or blow or strike or dodge. But he’s good with teamwork, with selling the idea of this group as a group. With the exception of that cornball farm shit back at Hawkeye Acres, all the personal-trauma stuff worked very well too. James Spader was very funny as Ultron, and Paul Bettany’s Vision reminded me of something I’ve heard from many older superhero fans, which is that once upon a time the Vision was the top-dog “cool” Marvel character, like Wolverine has been ever since. Sure, I can see that. Like all Marvel movies, even the best, it’s almost aggressively bereft of style, so the emphasis on charm is a necessary saving grace.

“Daredevil” thoughts, Season One, Episode Seven: “Stick”

April 23, 2015…But the biggest and funniest riff [“Stick”] played off the Daredevil comics involves the title character himself. Played by the wonderful Scott Glenn — who between this and his similarly weird role on HBO’s The Leftovers appears not so much to have aged with time but dried out like beef jerky — Stick was the martial-arts mentor who transformed Matt Murdock from a blind kid with uncontrollably sensitive senses into the black-clad badass we know and love today. As such, he’s given to a lot of portentous pronouncements: “You’ll need skills for the war,” “Surrounding yourself with soft stuff isn’t life, it’s death,” “They’re gonna suffer and you’re gonna die,” etc. In other words, he’s not a man, he’s a Frank Miller comic in human form.

Miller was just a kid trying to make his way as a comics artist in the Taxi Driver-esque mean streets of Carter-era New York City (he was mugged twice) when he parlayed a shot at the low-selling Daredevil comic into superstardom. It was he who gave the series its neo-noir makeover, incorporating techniques gleaned from American comics pioneers like Will Eisner as well as manga, Japan’s homegrown comics scene which at the time had very little readership in the West. His interest in ninjas, which he made a core component of Daredevil’s backstory, more or less singlehandedly shoved the concept into the American pop-culture mainstream: The ninja-heavy G.I. Joe characters and comics that Marvel developed owe him a great deal, and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were conceived as a straight-up Daredevil parody. (Ever wonder why the Turtles’ sensei was called “Splinter”? If you’ve met “Stick,” you know the answer.)

As time went on, Miller gave Batman an even more successful grim and gritty makeover in his seminal work The Dark Knight Returns, to which the Tim Burton and Chris Nolan movie franchises owe a massive debt. He also created series of his very own, like the hardboiled crime comic Sin City and the homoerotic historical fantasia 300, both of which became hit films. Meanwhile, Miller himself became more and more like a grizzled old hardass from one of his own comics, wearing a fedora and reminiscing favorably about the good old days when America’s heroes were of the two-fisted, square-jawed variety. So when wrinkly, stubbly old Stick compares Matt Murdock to the Spartans, “the baddest of the badasses,” it’s a 300 reference that winks as much at Miller himself as the comic in question. This helps keep his zen tough-guy routine on the show just this side of knowing self-parody, instead of the unwitting kind.

I reviewed episode 7 of Daredevil, and wrote a lot about Frank “The Tank” Miller, for Decider.

The Rise of ‘Guardians of the Galaxy”s Rocket Raccoon

July 30, 2014“You can only take these characters so far before it gets ridiculous,” Gunn admits. “Honestly, some of the latest superhero movies take themselves so seriously, they feel like a joke. This desperate, angsty need for ‘coolness’ is sort of pathetic. Guardians is a big reaction against that.” Will the grim-and-gritty-loving fanboys go along? Gunn laughs. “Who the hell knows?”

HBO, Marvel, and “The New Canon”

April 24, 2014I’m so wrong, but not in the way I might have expected. My students taught me that. They watch Netflix, and they watch it hard. They watch it at the end of the night to wind down from studying, they watch it when they come home tipsy, they binge it on a lazy Saturday afternoon. Most use their family’s subscription; others filch passwords from friends. It’s so widely used that when I told my Mad Men class that their only text for the class was a streaming subscription, only one student had to acquire one. (I realize we’re talking about students at a liberal arts college, but I encountered the same levels of access at state universities. As for other populations, I really don’t know, because Netflix won’t tell me (or anyone) who’s using it.

Some students use Hulu, but never Hulu Plus — when it comes to network shows and keeping current, they just don’t care. For some super buzzy shows, like Game of Thrones and Girls, they pirate or find illegal streams. But as far as I can tell, the general sentiment goes something like this: if it’s not on Netflix, why bother?

It’s a sentiment dictated by economics (a season of a TV show on iTunes = at least 48 beers) and time. Let’s say you want to watch a season of Pretty Little Liars. You have three options:

1) BitTorrent it and risk receiving a very stern cease-and-desist letter from either the school or your cable provider. Unless you can find a torrent of the entire season, you’ll have to wait for each episode to download. What do you do when it’s 1:30 am and you want a new episode now?

2) Find sketchy, poor quality online streams that may or may not infect your computer with a porn virus (plus you have to find individual stable streams for 22 episodes)

or

3) Watch it on Netflix in beautiful, legal HD, with each episode leading seamlessly into the next. You can watch it on your phone, your tablet, your computer (or your television, if it’s equipped); even if you move from device to device, it picks up right where you stopped.

It’s everything an overstressed yet media-hungry millennial could desire. And it’s not just millennials: I know more and more adults and parents who’ve cut the cable cord and acquired similar practices, mostly because they have no idea how to pirate and they only really want to watch about a dozen hours of (non-sports) television a month (who are these people, and what do they do after 8 pm every day?)

Through this reliance on Netflix, I’ve seen a new television pantheon begin to take form: there’s what’s streaming on Netflix, and then there’s everything else.

When I ask a student what they’re watching, the answers are varied: Friday Night Lights, Scandal, It’s Always Sunny, The League, Breaking Bad, Luther, Downton Abbey, Sherlock, Arrested Development, The Walking Dead, Pretty Little Liars, Weeds, Freaks & Geeks, The L Word, Twin Peaks, Archer, Louie, Portlandia. What all these shows have in common, however, is that they’re all available, in full, on Netflix.

Things that they haven’t watched? The Wire. Deadwood. Veronica Mars, Rome, Six Feet Under, The Sopranos.Even Sex in the City.

It’s not that they don’t want to watch these shows — it’s that with so much out there, including so much so-called “quality” programs, such as Twin Peaks and Freaks & Geeks, to catch up on, why watch something that’s not on Netflix? Why work that hard when there’s something this easy — and arguably just as good or important — right in front of you?

The split between Netflix and non-Netflix shows also dictates which shows can/still function as points of collective meaning. Talk to a group of 30-somethings today, and you can reference Tony Soprano and his various life decisions all day — in no small part because the viewing of The Sopranos was facilitated by DVD culture. Today, my students know the name and little else. I can’t make “cocksucker” Deadwood jokes (maybe I shouldn’t anyway?); I can’t use Veronica Mars as an example of neo-noir; I can’t reference the effectiveness of montage at finishing a series (Six Feet Under). These shows, arguably some of the most influential of the last decade, can’t be teaching tools unless I screen seasons of them for my students myself.

—Anne Helen Petersen, “The New Canon,” LA Review of Books

This absolutely fascinating essay makes the persuasive argument that HBO’s absence from Netflix, the television viewing mechanism of choice for a generation, means what those of us who are slightly older consider key, canonical shows simply aren’t getting watched anymore. It makes a great deal of sense: My own love of The Sopranos, Deadwood, and The Wire was enabled by DVDs, which were at the time the easiest, quickest, cheapest technology for viewing. Now that’s streaming, and those shows didn’t (until the recent Amazon Prime deal anyway) stream without a prohibitively expensive HBO-inclusive cable subscription, and they still don’t stream on the service of many people’s choice, so there’s a whole lot of potential Seans out there who aren’t ever gonna come across these shows. Technology — DVDs, DVRs, Netflix, streaming, even just the proliferation of cable channels and the concomitant need for more programming — played such a crucial role in the creation of the New Golden Age; it’s engrossing to see how it will help transform it and alter our perceptions of it in retrospect as well.

I should add that one of the reasons this article struck me so is that many of its lessons apply to another area of interest for me: Marvel Comics’ mismanagement of its backlist. Very quickly, even after its purchase by Disney, the company is still run by the man who bought it in, and brought it out of, bankruptcy in the late ’90s, Isaac Perlmutter. In many ways he still runs the place like the doors will close at any moment. Sometimes this makes headlines, as when the stars of Marvel’s films band together to demand higher wages; sometimes it’s fodder for jokes, like how Marvel’s publishing wing’s office space has a grand total of one available restroom per gender for hundreds of employees.

But it has a real impact too, in that books are constantly allowed to go out of print rather than commit to the cost of keeping them in print and available to retailers. Marvel makes an end-run around this by continuously repackaging and reprinting, but the net effect is that if you wanted to purchase a seminal, artform-altering run on a Marvel series — the Stan Lee/Jack Kirby Fantastic Four in its entirety, say, or the Stan Lee/Steve Ditko/John Romita Sr. Amazing Spider-Man — this is literally impossible to just hop on Amazon or go to your comic shop and do. At best, you’ll be able to cobble together a collection with different trade dresses, at different sizes, with different cover stock. In many cases you’ll just give up.

This costs Marvel money, obviously — I’d have plunked down $100 or whatever to buy all the Lee/Ditko Spidey and Lee/Kirby FF in one fell swoop years and years ago, if I could have. But it also costs them in terms of legacy — in terms of how readers and critics alike view their output. Compared to their nearest competitor, DC Comics, Marvel’s ’80s output never reached the heights of DC’s best work of the era, your Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One. But DC is equally adept at maintaining and selling B- and C-level books like Kingdom Come or the various Jeph Loeb Batman collections that Marvel can easily match or beat with things like Marvels or a solid Dark Phoenix Saga collection or Spider-Man: Kraven’s Last Hunt or even Daredevil: Born Again from the Year One creative team of Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli. But these titles are available sporadically at best, and have been in and out of print so many times that you’d be hard pressed to find two copies that even look alike. Compare that to how consistent, say, Watchmen has looked on store shelves for nearly three decades now.

Moreover, in terms of its 1960s Silver Age material, Marvel absolutely crushes DC. Artistically, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko were stylistic innovators who continue to influence the totality of the artform today, not just superhero comics but alternative and art comics as well. Narratively, too, ’60s Marvel basically invented the shared-universe template so much popular fiction follows today — sure, Batman and Superman teamed up from time to time, but the events that befell the Fantastic Four could change what happened to Iron Man or Spider-Man or whoever else. What’s more, those comics had a genuine sense of stakes their DC counterparts sorely lacked; I can’t tell you what an eye-opener it was to interview people as disparate as Gary Groth and Walt Simonson for the oral history of Marvel I did for Maxim a few years ago and hear that one of the things that impressed them about Marvel as kids was simply the fact that these superheroes actually got in fights. Such a basic component of how these stories are told to this day didn’t even exist before Lee, Kirby, Ditko et al did it. Finally, unlike DC, which has rebooted nearly half a dozen times, all those classic Marvel stories are still in continuity — they matter to the stories of those characters to this day. In all these respects those comics are valuable and readable to today’s readers; sure, they’re dated, but so is The Prisoner and The Twilight Zone, you know? A nice, uniformly designed collection of those runs would be invaluable to “fans,” to scholars, to cartoonists, to libraries, you name it. But no such collection exists. It’s not just money that’s left on the table, it’s the perception that the work is valuable and alive. And perhaps HBO, to a lesser but still significant degree, is weathering that exact same loss.

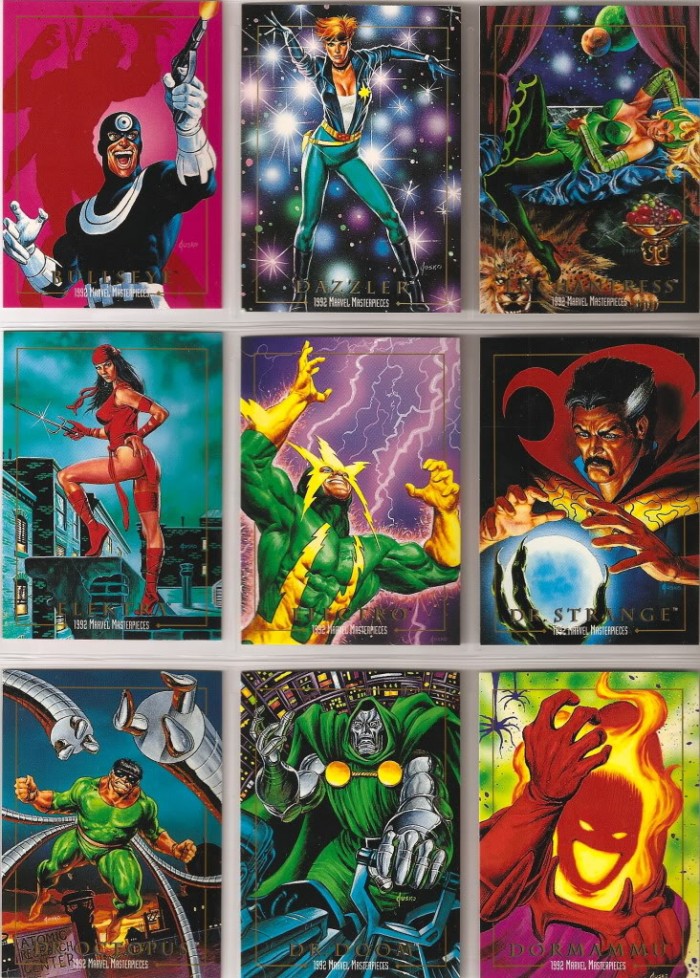

Comic cards, comic movie, comic

July 30, 2013I wrote about the early-’90s Marvel trading cards for Vorpalizer, explaining how for kids like me were our primary exposure to comics at all, and what that means.

I wrote about the history of Wolverine for Rolling Stone, marking the occasion of the release of the new movie The Wolverine by tracing how the Len Wein/John Romita Sr./Herb Trimpe–created, Chris Claremont/Dave Cockrum/John Byrne–developed character went from throwaway antagonist to one of the most popular in all of fiction.

And I wrote about Saman Bemel-Benrud’s webcomic Abyss for Vorpalizer, exploring its handling of information technology as a vector for the fantastic.

Comics Time: 67 monthly comics

October 23, 2012A couple weeks ago I realized I hadn’t read a single monthly comic book series since August 1. That’s the longest I’ve gone without reading a comic from the industry’s serialized backbone since I started reading comics in earnest again in the spring of 2001. Looking back, there were many reasons why I took this unplanned sabbatical, some of which it shares with my deliberate step back from writing about comics at the same time, but “I don’t enjoy these comics anymore” was not one of them. It’s an odd, transitional period for serialized action-adventure pamphlet comics, the kind people call “mainstream”: Marvel’s longest and in some cases best runs are all about to come to an end as they shuffle writers to new projects en masse, DC’s New 52 relaunch appears to have pushed my old favorite Grant Morrison into winding down his titles as well, and the Image-led renaissance in non-corporate non-shared-universe creator-owned comics may not be equal to its hype but certainly provides ample opportunity to read finely crafted action-adventure comics far removed from the line-wide editorial diktats of the Big Two. There’s an end of an era feeling in the air, and depending on how things shake out there may never again be a time when I’m reading and enjoying as many of these comics as I would have been reading and enjoying during those two and a half missing months.

So over the past two weeks or so, I crammed. Here are my impressions of the 67 comic books I read during that time, written in the order I read them. They’re all books I either have an established track record of liking or new titles I thought sounded interesting, so the result probably isn’t a useful portrait of What’s Not Working in Monthly Comics Today. The stuff I knew wasn’t working, I stayed away from. But I definitely didn’t end up liking everything I thought I’d like, and ended up liking some things more than I expected, so there are a few surprises in there.

Before I start, let me note for the record that this is absolutely the way to read these things, if you can help it: binge on them in big chunks. The serialized monthly comic is an almost uniquely inefficient and cost-ineffective art-delivery mechanism, so anything you can do to stack the deck in the favor of a satisfying single-sitting reading experience helps.

Avengers vs. X-Men #10-12, AvX VS #5-6: I liked this thing. It was certainly the best non-Final Crisis major line-wide event comic since Infinite Crisis kicked that era off. Wrapped up a lot of narrative and thematic threads from throughout the nu-Marvel era in fairly organic and enjoyable fashion. The action was engaging and intelligible, aside from a couple of weak spots (Bendis can’t write action and Coipel can’t draw it). The all-fight spinoff comic was a terrific idea–pure fluff, and a million times better than seeing the umpty-umpth splash-page melee with people shooting lasers in all direction that constitutes way too much superhero-comic action these days. I even liked the overall tonal progress of the series, how it went from being very much in line with Bendis’s usual seen-it-before military-superhero stuff to an X-Men mutant dystopia to a war of the gods, with the heroes flying and teleporting around from mystical cities to floating island prisons to Limbo to the moon, conducting their fights literally above the heads of the hoi polloi. Cyclops killing Professor X is a great story beat and I actually think this editorial/creative regime will make it stick for some time. And man, was it an orange book by the end. When I think of this series I’ll think of fire in the sky, which sounds really overdramatic and cheesy now that I’m typing it out, but it’s really not a bad look for an event comic to have a prevailing, lingering mental palette like that, one that overlaps with the overall tone and theme and story. If you’re predisposed to shit on this sort of thing nothing here will make you change your mind, but I’m almost always up for a good time at the movies and that’s what this provided me.

Action Comics #13 & #0: The bloom’s off the Morrison rose and he has no one but himself to blame, between a take on the Superman Year One concept and character that has never quite clicked, a relationship with the artists on this title that also hasn’t clicked, and a series of lame dodges and venal fuck-you-I-got-mine responses to creator’s rights issues either brought up by interviews or offered without prompting in his book Supergods. That said, these two issues contained my favorite aspects of Action Comics so far: the relatively convincing relationships between Clark Kent, Lois Lane, and Jimmy Olsen, here portrayed as young journalists getting a start in the big city by attempting to make uncompromising work, characters of a sort you basically never see; and done-in-one All Star Superman-style run-ins with Kryptonian villains, in this case the first criminal sentenced to the Phantom Zone. The art by Travel Foreman was memorably burned-looking, the take on the Phantom Zone creepy and unpleasant, and I’m a mark for Krypto stuff. It’s hard to take Morrison stories about the unbeatable power of good over evil when he abdicates any and all responsibility to behave ethically toward his peers and forebears IRL, but sometimes artists can lead you to the promised land but not enter themselves and that’s okay. Atheists write lovely hymns sometimes.

The Walking Dead #102, Michonne Special, and #103: One of the nice things about this series is that it can set up a new status quo, like Rick convincing his community of survivors to surrender to a more powerful and dangerous rival community, and you know Kirkman will have the follow-through to stick with this new status quo for, potentially, a year or more, and that when time’s up it won’t just get restored to the status quo ante. You can put up with a lot for that sense that “hey, this matters.” Over in the Michonne Special, which seamlessly edits an origin story written and drawn for Playboy (!) into a reprint of Michonne’s first appearance in the series, it’s striking how much Charlie Adlard’s art has changed from what looks now like an attempt to ape previous artist Tony Moore’s expressive, definitively delineated oblong faces into his own loose moody gray thing.

Uncanny Avengers #1: This is 99% set-up for future storylines, and said set-up is 99% angry superheroes telling each other how disappointed in each other they are, which I’d be happy never to read again. Rick Remender is an entertaining superhero team writer but much more so on certain titles than others, and this is an inauspicious start.

Powers #11: I was all set to say “so much time goes by between issues of Powers that you forget why you’re reading it anymore” but this issue was involving and lovely, with big breathless layouts in the big smackdown of Walker and Triphammer vs. some giant green god-thing and a moment that tied together years of storylines I’m surprised I remember. I see they’re going to relaunch the thing yet again as Powers Bureau, and we’ve seen this movie before: three or four on-time issues, then waiting five months each for the final two installments of the initial arc, then reading that Bendis and Oeming are back with a vengeance for the all-new story arc. I don’t look forward to the waiting or the fingers-crossed promises, but I do look forward to the reading. I wish Bendis would drop the assignments and the TV pilot that prevent him from putting out more of this, at a rate sufficient to help us forget we’ve seen a lot of these story beats before.

Invincible Iron Man #523-526: Not everything works in Matt Fraction and Salvador Larroca’s lengthy Iron Man run—the supporting cast at Tony Stark’s company resilient never distinguished themselves beyond “the people Tony and Pepper Potts banter with at meetings,” the stunt “casting” of, say, Nicole Kidman as Pepper lessened as time went on but was still distracting, and the less said about Tommy Lee Jones The Cussing Dwarf the better. But most of it worked very well indeed. Larroca’s art and Frank D’Armata’s colors look every bit as shiny and candy-coated and slick and future-ish as they ought to; nothing else in superhero comics looked like it in turn, that much I can say. Fraction gets Tony Stark as well as anyone this side of Robert Downey Jr., his intelligence and ego the only things that can get him into the scrapes he gets into AND get him out of them again — a great fit for Fraction as a personality based on what I can gather. Fraction’s Stark is just a pleasant character to spend time with. Plus there’s simply a lot to be said for guys in armor flying around punching each other. Even the Mandarin’s off-brand version of supervillain megalomania is compelling. This is one of the most consistently enjoyable superhero runs of the past decade, and I’ll be glad to see it end in a month or two only in the sense that then I can have a complete run of it.

Winter Soldier #9-11: Speaking of lengthy runs that are about to wrap up, Ed Brubaker’s tenure on Captain America and its assorted spinoffs is nearing the finish line, too. Just a wonderful match of writer to character, even if everything after Steve Rogers’s return from the dead has felt a bit like gilding the lily. The artists on the main title have strayed from the visual template established by Steve Epting and Mike Perkins back in the day, but here, Butch Guice is working right in that “naturalist depictions of superhero antics” sweet spot that made Bru-Cap the perfect blend of black ops, superspy, and Star-Spangled Avenger. Most of the time, at least — other times it looks like he’s just tracing photos to save time. It’s weird, how dramatically it shifts. Nice colors from Bettie Breitweiser, though, working in the teal-and-orange palette of Jimmy Corrigan’s cover and simultaneously muted and garish at the same time. Kind of glo-fi on occasion. Finally, Black Widow fights Bucky while wearing a ballerina costume.

Invincible #94-95: Here Kirkman gives us a sort of My First Sony version of the old sci-fi trope where centuries pass for characters stranded on an alien world while they and the Earth they come from barely age at all. The disconnect between the immensity of that experience and demeanor of the characters involved is so massive it’s all but played for laughs, but given the fact that these are two very much supporting players and yet the book is still spending issue after issue on this story, it’s still an entertaining example of Kirkman’s willingness to both go big and go offroad. Series co-creator Cory Walker draws the alien-world stuff; I think his design for the grown-up Amanda Monster Girl is hella cute. I’m always glad to have read Invincible when I put it down because I never know where it’s headed when I pick it up–I certainly didn’t see this storyline coming. Who could’ve?

B.P.R.D. Hell on Earth: Return of the Master #1-2: Tyler Crook had the thankless task of following the great Guy Davis on this title (literally thankless in the sense that Dark Horse barely said boo about Davis’s departure–I still scratch my head about that) and preceding the tour de force monster on monster combat story arc illustrated by James Harren. So you can hear the collective kvetching when he’s on duty. But his work is just fine — not as creepy as it should be, perhaps, but very expressive, which was always the other big tool in Davis’s arsenal. I’d rather have good acting from the characters than super-scary visuals, frankly — it’s made the relationship between the secretly evil Russian zombie guy and his imprisoned immortal-little-girl predecessor at the top of Russia’s BPRD equivalent a lot of fun to watch, for example. Anyway I feel like the best thing for the Hellboy/BPRD saga would be for it to end in the middle-term future — it’s been a marvelous, unpredictable, evocative ongoing series but it needs a true ragna rok to stick. Hopefully we’re headed there.

Lobster Johnson: The Prayer of Neferu: You could go either way with these Hellboyverse spinoffs and say that their tangential relationship to the main story helps them — they’re looser and freer and less burdened by a sense of building to a climax that never comes — or hurts them –it’s not the character-based Lovecraftian good stuff so who cares. I guess I’m in the former camp for this one. Wilfredo Torres’s faces are a bit too obviously photoreffed but ooftah, that line of his! Loose, thick, luminous, lively. Shades of Dave Stevens, maybe. Meanwhile, Lobster Johnson crashes a party full of gangsters and reincarnated Egyptian occultists and sticks around until he’s managed to kill all of them, then leaves. Ruthlessly efficient.

Uncanny X-Force #29-32: Four issues in two months. This doesn’t bother me like it’s bothered a lot of people, since I haven’t seen any dimunition in the quality of the stories Rick Remender’s telling, and the art, while inconsistent, is always competent and almost always colored by Dean White, one of the best in the biz and the book’s aesthetic lynchpin. Granted, though, he’s less in evidence by the end of this little run, and that’s a loss. Anyway, no, generally I’m fine with lots of Uncanny X-Force. This run made me realize how much Remender is willing to stack the deck against his own theme. The idea behind Uncanny X-Force is that violence poisons the souls of those who commit it, even for the right reasons — and not in the usual, hardass, “down these mean streets a man must go”/”you want me on that wall” way that books starring the Punisher and Wolverine usually approach this stuff. No, all the characters here, their lives are legitimately worse than they were before they signed up, and they know they have only themselves to blame. The interesting thing there, though, is that Remender pursues this theme in the face of antagonists who are just out-and-out monstrous psychopathic villains with “does what it says on the tin” names like Apocalypse, Dark Angel, and the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants. (He’s done the same thing in Secret Avengers, too, resurrecting the Masters of Evil.) X-Force’s opponents either have evil in their name or preside over alternate realities where the consequences of not stopping them are visible everywhere. Yet the message, that engaging these thoroughly awful murderers by murdering them in turn is wrong and destructive, remains. It’s exciting to see someone willing to make extra work for themselves to make their point stick.

Batman Incorporated #3 & #0: Morrison’s still got the fire here, I’ll say that much. Obviously having Chris Burnham and Frazer Irving in your corner goes a long way toward creating that impression — Burnham’s taken Frank Quitely’s pointillist approach to action and made it his own, and Irving can just do so much with so little, from boiling chase sequences down to figures made from little shapes of color to drawing gorgeous Jonny Negron-style hip ladies getting down. But the story itself remains engaging, giving the impression that you’re about five feet away from being able to see the whole picture, but it keeps advancing right along with you to keep the answer to the mystery tantalizingly out of reach. That’s how Morrison’s been handling his conspiracy-based Bat-run for years and years now, and it remains an electric read, even if his concept of a corporation dedicated solely to do-gooding now reads like pure projection. Or perhaps it’s not “even if” but “because,” I don’t know.

Happy #1: We all get it: Morrison’s doing a parody of Mark Millar and Garth Ennis, with Ennis collaborator Darick Robertson riding shotgun. That’s nice, I guess, but as far as this first issue is concerned, it’s all set-up and no subversion. It simply reads like a undistinguished example of what one assumes he’ll be sending up in a more ambitious fashion by series’ end. It’ll be a bit of a slog getting there with these undistinguishable foul-mouthed hardasses vomiting f-bombs at each other. Still, I like Robertson’s art well enough — maybe it’s just reading this and Batman Incorporated back-to-back that did it, but now I can see his influence on Burnham, and that influence is reflected back in a way that makes me appreciate him more.

Secret Avengers #30-32: Compared to writer Rick Remender’s similarly structured Uncanny X-Force, there’s just…not a lot going on here. The closest it gets to a theme is the use of Marvel’s various android characters for a look at what makes us human, an issue I’ve never felt compelled to grapple with, seeing as how the question is basically answered every second of every day you get up in the morning. Nominally this storyline is the payoff to a grand mystical conspiracy introduced by Ed Brubaker in the inaugural arcs of the series before he realized he doesn’t like writing team books and bailed, but the payoff is a dud — literally, pretty much, as nothing happens when the archvillain pulls the trigger on the superweapon he’s spent the entire series to date preparing. The figurework by Matteo Scalera is scratchy and elastic in a way that softens the impact of the black-ops and hand-to-hand combat that drives the story. It’s inoffensive, and occasionally fun, but extremely slight — exactly what I’d worried it would be after that initial preview issue back when, and impossible to overlook now that it’s not being papered over by the lovely cosmic artwork of Renato Guedes and Bettie Breitweiser from the Avengers vs. X-Men tie-in arc.

Lobster Johnson: Caput Mortuum: And this one is super-duper slight, yet its mere presence in the Mignolaverse, the implacability of its lead “character” (Lobster Johnson is something of a deliberate cipher), and some exciting action stagecraft played off of Tonci Zonjic and Dave Stewart’s solid and efficient artwork make it feel like a much more worthwhile affair. It’s weird to read a Hellboy/BPRD-related book without a single hint of the supernatural — this is just a vigilante against Nazis with an advanced chemical weapon — and that may speak to the overextension of the concept generally, but not enough to complain about the particulars.

Captain America #16-18: Well, this is a bummer. After a near-decade run that was arguably the best in the character’s history, Ed Brubaker hits the eject switch from Marvel in favor of TV projects and creator-owned stuff, and in the confusion a co-writer is roped in to handle his final full arc on the title, which seems to mean scripting off of Bru’s plot. So a long-running storyline about Cap’s primary antagonist for the past year or so is basically taken out of Brubaker’s hands, with even his trademark, claustrophobic narrative captions removed, and the result is just unspectacular superhero boilerplate. Doesn’t help that artist Scott Eaton isn’t elevating the material, although the menagerie of three inkers and two colorists he’s saddled with in issue #16 don’t exactly give the impression that this is the thought-through product of a singular vision either. I believe Brubaker’s getting his very own farewell issue, at least, but this is a pretty depressing example of Marvel’s need to move product trumping what had been one of its creative highlights for literally years. If you’re keeping track, it’s much worse a sin than the cast of thousands necessary to make Uncanny X-Force a biweekly title, but way better than Brian Bendis being forced to unceremoniously kill off Ultimate Spider-Man after well over a hundred issues and replace him with an interesting character hamstrung by a gross tribute to union-busting school-“reform” propaganda film Waiting for Superman because Mark Millar tossed out the phrase “Death of Spider-Man” on his way out the door of a creative summit.

Prophet #28-29: This series has been just fantastic, a most welcome addition to the few, the proud, the “who knows what the hell’s going to happen when you open any given issue of this book?” monthly series. Deadly serious yet never humorless — a trick known to its pulp antecedents (it’s very much Space Conan) but hard to pull off in the present day. The scale of this “literature of ideas” take on SF is just phenomenal — all the concepts are just so big! It’s the universe as a massive, rotting body, with each individual alien or warrior or creature or robot the tiniest of molecules in the tiniest of cells in some small organ or digit somewhere, locked into a life-and-death drama with no sense of its own inconsequentiality relative to the grand scheme of things. It’s actually rather breathtaking. The rhetoric surrounding the comics of Brandon Graham, who here is “just” the writer where elsewhere he does the lot, has been messianic enough to make the most ardent Grant Morrison fan blush (I know whereof I speak there), and I personally bristle at his boilerplate Chris Ware disses, but there’s no sign of any of that affecting his work for the worse here. Even his use of puns, perhaps his greatest vice elsewhere, is judicious and illuminating (“mind field” instead of “mine field” is the main one here, and it’s an evocative and informative turn of phrase). Graham has a stable of talented off-model sci-fi artists to work with, though the standout here is the stunning gray-white color work of Joseph Bergin III and Charo Solis in issue #29. Realizing the connecting thread to the series’ done-in-one format was one of my favorite eureka moments in the past couple years of comics, and it continues to be one of the book’s great delights. Simply a pleasure from start to finish.

Fantastic Four #609-611 and FF #21-22: Writer Jonathan Hickman wraps up his long-running, interlocking dual Fantastic Four series with a series of one-shots and two-parters dedicated to individual subplots and supporting characters. That’s a fine note for the series to end on, as I’ve always been much less impressed by its long-game clockwork narrative structure — for all the breathlessness of Hickman’s writing this has always felt like an academic exercise to me, tied neither to a Morrisonian sense of creepy mystery nor a Moore-style autopsy of humanity’s inevitably failed attempts to remake the world in its own image — than by the way it simply places likeable characters with fun powers in close proximity with big cosmic superhero sci-fi ideas. It’s tough to go wrong with that, or at least it should be. I like Hickman FF less than Fraction Iron Man or Brubaker Cap, but I still like it, and as with those other series I’ll be glad to have The Complete Jonathan Hickman Fantastic Four &c on my bookshelf.

Green Lantern #12, Annual #1, #0, and #13: I’ve always thought Geoff Johns’s Green Lantern run works because a) he cracked open the concept and found a whole new world of possibilities inside, and b) those possibilities stem from the childlike simplicity of “what if there were other colored power rings?” which is pure inner-eight-year-old gold. But this recent stretch of GL books (and good luck figuring out what to read in what order, all those new readers attracted to comics for the first time by the New 52, we know you’re out there) makes me realize something else that’s going on here: Green Lantern is a daytime soap opera, but instead of rival families, there are rival lantern corps. There’s that same neverending roundelay of emotionally pitched, for-all-the-marbles confrontations that, miraculously, just seem to break down and reconstitute themselves with a different alignment of the players a few months later down the line. Right now, Hal Jordan and Sinestro are allies against the Guardians, who are using Black Hand in a plot against all the lanterns. A few months ago Hal and Sinestro and the Guardians were united against Black Hand. Before that Hal and the Guardians were united against Sinestro. And so on and so on. I like these characters and concepts, and I like the artists who draw them (particularly Doug Mahnke, who gets a nice glory shot of the Justice League on the final page of #13), so I’m up for watching the kaleidoscope shuffle and realign. As a side note, the last couple issues see the introduction of a new Arab-American, Muslim Green Lantern, who is recruited by Hal and Sinestro’s shared power ring while he’s in the middle of being wrongfully accused of, and tortured for, terrorism by the American government. That’s a super-duper progressive superhero origin, and one that’s likely to be a lot more timeless than Greg Rucka’s Batwoman character becoming a vigilante after getting bounced out of the military under Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. Depending on whether you choose to emphasize the progress of gay rights or the rise of open Islamophobia, this is a real half-full/half-empty situation.

Marvel Now Point One: This is an anthology one-shot featuring various prologue short stories by various creative teams of various upcoming titles. I’ve read around 40, 50 monthly comics in under a week at this point in this little project, and I could make heads or tails out of a grand total of one of these stories. (The Fraction/Allred/Ant-Man one, a teaser for a future Fraction/Allred FF book I won’t be reading because Allred did a variant cover for Before Watchmen, which is the same reason I’ve dropped Mark Waid’s Daredevil now that Before Watchmen cover artist Chris Samnee is the regular artist. Both of these men can get out of Before Watchmen Scab Limbo by donating their proceeds to charity, Paul Pope style!)

B.P.R.D.: 1948 #1: This is the first BPRD comic to spook me in a while, mainly because I find the thunderbird legend deeply unnerving. The idea that even as well-trod a territory as America is big enough to house a relict population of birds the size of a city bus…I don’t know, it’s like staring into the ocean or the night sky in some way. The bird in this BPRD comic isn’t a bird at all, mind you, it’s a cthulhoid monstrosity of the Hellboy/BPRD kind, but it’s playing with thunderbird imagery and it’s creepy. I like it.

Godzilla #4-5 and Godzilla: The Half-Century War #1-3: If you’d told me this time last year that I’d soon be reading not one but two beautiful, rollicking comic book series starring Godzilla and drawn by artists on the alternative-leaning side of indie comics, I never would have believed you, but lo, it has come to pass. I never talk about this for some reason, not even relative to stuff like He-Man or G.I. Joe, but I was a huge, huge Godzilla fan as a little kid, with the stack of VHS tapes featuring three movies taped off Channel 11’s Saturday matinees per tape to prove it. These comics do what those movies did: Create reasonably engaging human characters to provide a worm’s eye view of these giant, magnificently designed and imagined forces of nature as they wreak havoc and attack each other. The main title, written by Duane Swierczynski, is sort of the action-comedy/tween-boy animated-series version of the concept, starring a not-at-all-veiled Jason Statham figure as he and his team fly from place to place, taking down giant monsters for large sums of cash. It features the art of Simon Gane, which looks like it was assembled by tracing the wrinkles on crumpled-up aluminum foil, and I mean that in the best way. The monsters look solid, and they pop off the rubble and explosions. Even more impressive is the James Stokoe written/illustrated Half-Century War, which reads like what it is: An already talented and established cartoonist given the reins of something he loved as a kid and given carte blanche to do his own thing with it. This one’s slightly more serious in tone, in the way that monthly action-adventure comics can be “serious,” but it’s primarily a fun-for-fans Ultimate Godzilla, or maybe Marvels Meets Godzilla, that plays with the timeline established by the Toho movies in a sort of real-time way. There are a couple of spreads — the debut of Godzilla’s trademark sound effect and a giant-monster battle royale — that made my jaw literally drop.

Batwoman #12, #0, #13: An unnecessarily beautiful series, co-written and illustrated by J.H. Williams III with color by the amazing Dave Stewart. I mean, this thing…Batwoman has an enormously overcomplicated history in her few short years thanks to co-creator and original writer Greg Rucka’s fondness for some truly dopey ideas, some of which (the half-animal guys that are the rare thing Williams is bad at drawing) linger to this day, but holy god is it a thing of goth glamour and splendor. The reds in the zero issue are worth buying the damn book for. Twelve and 13 are done almost exclusively in two-page spreads, because why not? There’s a spread where Batwoman and Wonder Woman burst out of the goddess of night’s lair by lighting a match that made me say “Jesus!” out loud, it was so stunning. I’m basically sticking with this book on the off chance my daughter turns out to be a Hot Topic shopper in her teens, because this is really remarkable for that demographic, and purely in visual terms for me as well. They really ought to do whatever it takes to prevent anyone but Williams from drawing it, though. (PS: Regarding something I mentioned earlier, I notice they’ve now begun glossing over the fact that she was drummed out of the military by Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, instead simply saying she was kicked out of West Point.)

Glory #29: Joe Keatinge and Ross Campbell’s contribution to the same Rob Liefeld reboot line that spawned Prophet is goofily beautiful — there’s a panel of the main human character Riley smiling as her hair’s black tendrils blow in the chilly wind that I sat and looked at for a solid minute — and the character designs reveal Campbell to be just as proficient with genre body types as he is with the skinny/chubby/everything-in-between goths in his moody slice-of-lifer Wet Moon. This one actually has a couple of post-coital scenes, which means you get to see his hulkingly muscular version of the title character, who used to be just kind of a Wonder Woman knockoff from what I understand, in all her glory, and it’s a hilariously transgressive image. It’s tough to say where this series is headed because there’s always this disconnect between the calm demeanor of the characters and the inevitable slaughter they’re constantly talking about being headed toward, but it’s a really attractive book in the meantime.

Fatale #7-8: This is the first disappointing Brubaker/Phillips collaboration I’ve read. The combination of supernatural horror and noir just doesn’t work: the past-tense neurotic noir narration smothers any potential to present a super-rational shock in the moment, Phillips isn’t really a natural when it comes to framing horrific imagery, and Brubaker’s giving him basically nothing to work with beyond “spooky guys who sometimes have Cthulhu heads.”

Mars Attacks #3-4: Good clean fun. John Layman and John McCrea take the BEMs from the gruesome old Topps trading card series and let them run amok among various action-movie and alien-invasion cliches. This feels like someone’s action-pastiche comic you picked up at BCGF, only it looks like a book that runs in the front of Previews. That’s a fun feeling! These issues featured giant praying mantises eviscerating a college class, and that made me laugh. Very much in the vein of the Godzilla series also published by IDW. I could stand more books like this, sure. Cheap pulp kicks.

Hawkeye #2-3: I hate to use the term Mary Sue, but suddenly Hawkeye’s a down dude who lives in Brooklyn where he attends rooftop parties with his neighbors, he loves 1970 Dodge Challengers, and he’s as irresistible to women as billionaire playboy Tony Stark and famous lawyer Matt Murdock, so what else do you call it. How any of this squares with the basics of the character — why he suddenly lives in Brooklyn instead of wherever it is that the Avengers live, why he’s a super-cool dude instead of the ex-circus ex-con archer guy…I dunno, it feels like Matt Fraction poured a bunch of unrelated ideas into a Hawkeye-shaped vessel because that’s what was available. I’m not saying there’s some One True Hawkeye out there, I’m saying I don’t think Hawkeye, One True or otherwise, is anything but an extraordinarily flimsy frame on which to hang surface-cool writing like this. At least we’re past the Russian guy who said “bro” all the time from the first issue, Fraction’s worst writing since the cussing dwarf from Iron Man, but these issues also set up the distasteful idea that Hawkeye and the girl who took over for him in the Young Avengers want to fuck but think it’s a bad idea, so it’s hardly a step in the right direction.

Fatima: The Blood Spinners #3-4: Gilbert Hernandez’s heretofore relatively lighthearted zombies-getting-shot-in-the-head epic takes a sharp left turn into Sexual Unpleasantnessville, with a pair of mutant-slug-rape-pregnancy scenes that even in this Prison Pit era have the power to shock and horrify. Yet the series maintains its just-another-day-at-the-office tone, from its flat-affect heroine Fatima on down. The matter-of-factness with which Beto presents violence and depravity in this and pretty much all of his postmillennial comics is as harrowing a vision of the world as any cartoonist has ever had, though I can certainly see why lodging such nihilism in an action-adventure romp starring a beautiful lady in super-cute short shorts sits ill with some readers. Gilbert doesn’t make it easy on anyone.

Made Mine Marvel

May 14, 2012Last week I saw The Avengers and its immediate Marvel-movie predecessors, Thor and Captain America: The First Avenger. (And just for reference: Iron Man, The Incredible Hulk, Iron Man 2.) Here’s the most important part of the following review of these three films: I gave three times as much to The Hero Initiative upon viewing them I did to Marvel and its business partners. Yes, this means that I gave Marvel and its business partners a non-zero amount of money to see these movies, more than they gave the family of Avengers/Iron Man/Hulk/Nick Fury/Captain America/Thor co-creator Jack Kirby (who despite what you may have heard did receive a brief on-screen credit, for what it’s worth) for making these movies possible. That’s deeply unfortunate and deplorable and wrong, and as both an occasional freelancer for the company and a fan of any number of its comics and creators, I encourage Marvel to change its tune on this matter, just as I encourage those of you who pay money to watch these movies to give an equal or greater amount to The Hero Initiative to help take care of creators who are in need because the companies they built never did so themselves. Indeed the bad taste in my mouth would have kept me from going to the movies to see Avengers at all but for the intervention of, literally, my three oldest friends, who were in town and wished to recreate our summer-blockbuster theater trips of old. When life gives you $4 concession-stand sodas, you make lemonade, I suppose.

First, I watched Thor. It was bad, pretty much. I mean, it had its moments, largely via the fantastic casting of its two leads, Chris Hemsworth and Tom Hiddleston as Thor and Loki. Think of what an unwatchable turd this would have been if those two had been less committed and gleeful about their ridiculous shouty roles! Space Éomer and Cosmic Wormtongue were a real coup, especially given how important Hiddleston’s Loki ended up being for The Avengers. A tip of the hat to Kat Dennings as well for her turn as the kind of sarcastic, kind of dopey friend/assistant. In a film as flatly functional as this one was, any part that that isn’t strictly required to advance the narrative should be celebrated, and Dennings made the most of it, especially when required to embody the female gaze while Thor walked around with his shirt off. For real, the presentation of male superheroes as eye candy for the female audience in both this and Captain America is a funny, smart, sexy, and welcome development — imagine if the comics had the stones to do something like that!

So yeah, that was good. So was the reasonable gravitas projected by Stellan Skarsgaard and Idris Elba in their supporting roles as a scientist and the most interesting Asgardian — y’know, they got the job done. And the big epic visuals were surprisingly effective as well. It wasn’t Kirby, of course, nothing but Kirby himself is, but I thought the golden architecture of Asgard was suitably grand and smartly designed; the Bifrost’s spherical teleportation mechanism was a memorable bit of business, for example. Meanwhile, the closest the film got to saying something really unexpected and smart was its frequent use of awe-inspiring rainbow-colored shots of the distant stars and galaxies, implying that the reality of our universe is at least as amazing and unknowable and impressive as anything a science-fantasy can conjure up.

The rest of it, of course, was the purest anonymous hackwork from Kenneth Branagh. I’m really hesitant to ever use the h-word simply because I’m not a mindreader and don’t presume to know whether an artist really was just banging something out for cash, but in Branagh’s case we have enough of a track record on other projects involving adaptation and interpretation to see how rote this Lord of the Rings knockoff really is. Dull would-be sweeping opening narration. Vast armies of undifferentiated CGI baddies. A band of warriors distinguished solely by their hair. Purple clichés like “You’ve come a long way to die, Asgardian” and “Allfather, we must speak with you urgently” dropping like bricks from the mouths of flimsy supporting actors, as if someone had taken the “give up the halfling, she-elf” line from the Jackson/Walsh/Boyens Fellowship of the Ring adaptation and made an entire screenplay out of it…gah, what a tedious and derivative mess.

Just as disappointingly, Branagh displays no proficiency whatsoever for directing action, and that really could not be more crucial to making a good superhero movie. The frost-giant fights were murky and lazy, just a bunch of people swinging things around and knocking things over. Worse still was Thor’s break-in to the SHIELD compound, in which what could have been a Bourne-style tour de force of ruthlessly efficient takedowns became a supporting-card match-up between pro-wrestling jobbers who don’t know how to sell. You got that one big wish-fulfillment moment when Thor got his powers back and took the fight to the Destroyer, where you’re like “Yesss, that’s what it’d be like to wield the hammer of the gods, Robert Plant was totally right,” but that was about it. No, wait, there was the scene where he beat up a hospital room full of doctors and nurses, but the success of that sequence had more to do with how odd it was to see something like that in a hero’s-journey-by-the-numbers flick like this than for particularly memorable ways in which to coldcock phlebotomists.

The key non-Hemsworth/Hiddleston performances were pretty brutal to watch, too. Anthony Hopkins eats so much scenery that I suspect the Odinsleep is actually a diabetic coma. Natalie Portman as the love interest is just horrible, like her insufferable Garden State character got an astrophysics doctorate. She’s one of the most beautiful human beings on God’s gray earth, yes, but has she ever been good in anything not Closer or the SNL thing where she cursed a lot?And that’s when you start paying attention to the plot and realizing how flimsy that is, too, even beneath the actual good performances. For example, both Portman’s Jane Foster and Hiddleston’s Loki undergo 180-degree reversals of their entire lives up inside, what, 48 hours? The brilliant astrophysicist takes the word of a person she has no reason to believe isn’t mentally ill, because he’s hot and SHIELD is mean? Everything here happens because it must, because that’s the kind of movie this is. Take away Hemsworth and Hiddleston’s joie de vivre and you’ve got Marvel’s 2nd-quarter financial report, not a movie.

(I will say this for it, though: Making Thor’s opposition to genocide the hinge on which the climax swings is a very interesting, and frankly wonderful, idea. Given that writer Geoff Johns just used the commission of genocide as a way to get his new, younger, tougher version of Aquaman over with the audience of his comic, apparently successfully, you can see that this could very easily have gone the other way. More easily than the way it went, in fact.)

Captain America: The First Avenger, though? This thing was pretty good. It had heart, and it had wit, and it had smarts. First, the heart: a warm, slightly sad performance from Chris Evans (!!!) as Steve Rogers, one that made him feel as much like a man out of time during World War II as he would later in the present day. I understand that the line in which Steve presents his zeal to enter the Army and fight the war not as a hankering to kill Nazis but as a deep-seated dislike bullies of all shapes and sizes, given that he’d been victimized by them his entire life, was a Joss Whedon contribution, so good on Whedon; that cracked open that character and showed me what’s inside in a way that no other interpretation of him, not even Ed Brubaker’s fine ongoing multi-series megastory of the past half-decade or so, has done. (As an aside: Jeez, does this version of Cap reveal Mark Millar’s line from Ultimates, “You think this A on my head stands for FRANCE???”, as the single worst comics line of the decade or what? Shame, shame, shame on me for not seeing it at the time. And for many other things besides, but mostly that, for our present purposes.)

Then the wit. Unlike Thor‘s random, listless swinging of arms and knocking-about of bodies (seriously those fight scenes played like my baby daughter tearing into block towers), Captain America‘s director Joe Johnston made his fight scenes memorable by dint of effort and attention to detail. He figured out like maybe no one ever has before how to make Cap’s nebulous “peak human ability” not-quite-a-power-set work in the context of action: Imagine the coolest, most amazing possible move a person could make, if they were both as skilled and as lucky as they could possibly be, then imagine a guy who can make move after move like that, without fail. If he leaps, he’s going to make it. If he dodges, they’re going to miss. If he shoots or throws or punches or kicks, he’s going to hit the target.

Johnston peppers the action sequences with little flourishes of visual imagination and humor, too: using multiiple countdown clocsk for the destruction of the Hydra lab instead of just one; the Red Skull firing off a dud round with his magic laser, then trying again, then nodding with self-approval when it works this time, like “Ah, there we go”; ending a “he’s got a gun on the kid!” hostage situation by having the bad guy toss the kid into the water, only to discover him treading happily, telling Cap, “Go get him! I can swim!” Even the gunfire, of which there was a surprising amount for a superhero movie, felt concrete and dangerous without being grotesque, in that bloody/not-bloody Indiana Jones way.

Indy, of course, is the film’s lodestone, from the Nazi-relic-hunter maguffin on down. The trick–and this is where the smarts come in–is in flipping the Indiana Jones conventions around in novel and entertaining ways. The film begins with the Nazis successfully acquiring and using the magical artifact rather than being a race to stop this from happening. The places-on-a-map travel montage doesn’t depict Cap’s quest across the globe, but his USO tour. Cap is the good-hearted mensch who recruits affable rogues to help him, not the other way around. And Cap actually gives himself over to the ameliorative, sacrificial oblivion that Indy always seemed required to surrender to, only to save his own bacon at the last moment.

Moreover, a few of Captain America‘s shrewdest moves have multiple purposes. Chris Evans joins Chris Hemsworth on the list of Marvel men whose bodies are presented unambiguously as sex objects, somehow threading the needle between appealing to women without turning off men — four-quadrant success, here we come — but also selling a historically undersold dimension of superhero physicality. (No sculpted-muscle rubber bodysuits required here!) Making Hydra a cult of personality in service of the Red Skull both obviates the need to keep the icky Nazis a key part of this international-audience family blockbuster, but it also provides an explanation as to how its marvelous, anachronistic weaponry never spread outside the narrow conflict between Hydra and Cap’s crew, altering both the war and the course of human history.

Cap also boasts the liveliest supporting cast of the bunch. Like Thor, it could probably have gotten away with its core protagonist-antagonist pairing, the strong performance from Evans and the delightfully cartoonish villainy of Hugo Weaving, who knows from cartoonish villainy. (And dig the voice: Hugo Weaving presents Werner Herzog as the Red Skull! He joins Daniel Day-Lewis as John Huston as Daniel Plainview and Heath Ledger as David Lynch as the Joker in the pantheon of Great Movie Villains Who Sound Like Great Movie Directors.) instead it gave us Tommy Lee Jones’s most effective turn as himself this side of The Fugitive and No Country for Old Men, Hayley Atwell as a believably steely and caring Allied intelligence operative, and lookalikes Sebastian Stan and Dominic Cooper as tough-guy Bucky and swaggering scientist Howard Stark, a pair of alpha males working different angles on that role and quietly setting an example for Steve as to how he does and doesn’t want to behave himself.

I don’t mean to oversell Captain America, mind you. It could just be my decade in the sausage factory souring me on its prospects for capturing the imagination of a generation the way Indiana Jones did for me, but I can’t help but feel it’s not going to be returned to in quite the same way. It almost certainly won’t by me. But it feels like a film, a work of art/entertainment with a unique personality and point of view which one could locate in its director’s overall oeuvre, in a way that Thor simply didn’t. It does more than what is strictly necessary and sufficient, and that can be a lot.

Which brings us to the crown jewel in the Marvel Studios “cinematic universe,” Joss Whedon’s Marvel’s The Avengers. Two of my favorite elements of this film never even appeared on screen. Rather, they were in my head, as I pictured rooms full of multi-millionaires putting their heads together about the Hulk and concluding “Nope, we can’t make this guy work for movie audiences, let’s kick it to Jeph Loeb for a TV show,” and another room full of multi-milloinaires putting their heads together about Joss Whedon and concluding “Nope, we can’t make this guy work for movie audiences, let’s scrap his Wonder Woman movie and concentrate on Green Lantern.” I’m a big believer in the Hulk and completely agnostic about Whedon (this screening popped my Joss Whedon live-action cherry, as a matter of fact), but I’m bullish to the fucking extreme on Big Two corporate execs eating crow, so way to go, Avengers!

Beyond that? Every lead actor not a SHIELD agent was just terrific, all the action and fight sequences were wonderful, and everything else was boring. Was it just me or was the film one-third uninteresting espionage, one-third flabbily written “we’re not so different, you and I” attempts at revealing character through various antagonistic dialogue pairings, and one-third wish-fulfillment/celebration of competence and cooperation/checking off items from the fanboy wishlist one by one? Could we not have expanded that last third to encompass the entire film?

To expand a bit, I realize Whedon deserves basically no credit for the cast—aside from the wonderful Mark Ruffalo, his primary contribution was Cobie Smulders; everyone else was imported from the other Marvel movies. And I realize that when they weren’t running around punching things, Whedon’s screenplay was an enervating, unfunny mess. I laughed a grand total of three times: “Legolas”; the thing where the Hulk just slams the shit out of Loki–that one brought down the house; and the shawarma stinger, which nevertheless made me feel like I did the first time I sat and watched all the way through the closing credits of Monty Python and the Holy Grail because my best friend, who accompanied me to Avengers by the way, told me something awesome happened at the end. The non-fight stuff was tepid enough to get me thinking about plot holes, even. Quick: What’s German for “Sorry, sir, but I don’t speak a word of English?” If the Hulk is always angry and thus always in control of his transformations, then shouldn’t he go to jail for hulking out and attempting to hunt down the Black Widow and beat her to death? Why are we and the characters supposed to care so passionately about Agent Coulson, a guy whose job is to lie about things and bigfoot everyone in the name of almighty Security? Why does the allusion to the Holocaust in the Germany sequence feel so much more tasteless than the use of actual Nazis as antagonists in Captain America?

And yet! Somehow Whedon and his spotty script never got in the way of what made each of the leads compelling and entertaining to watch. Even aside from obvious highlights like the Downey Jr./Ruffalo buddy comedy, or the relationship between Scarlett Johansson’s Black Widow and the always excellent Jeremy Renner’s Hawkeye (you see their scene together and picture an alternate universe in which they’d co-starred in an autumn indie drama of mild renown), or the Hemsworth/Hiddleston reunion, I was just happy to watch all the superheroes walking around and talking even when I was completely bored by what they were saying and doing. I’m not sure I can think of another film like that (not that I’d necessarily want to).

It’s really the fights that made it happen. Like Johnston and Jon Favreau before him, but now multiplied out to half a dozen characters, Whedon understood each character’s unique power or skill set, what makes them exciting, and how best to showcase them in a fight. Thor’s hammer-and-lightning was a pleasure every time, not just in one big moment of glory. The Hulk was alternately terrifying and utterly joyful, as the Hulk ought to be. Cap once again rolled a 20 with every saving throw, and added to that repertoire a ground-level mastery of tactics that served the dual purpose of explaining to the audience why he was in charge rather than Iron Man and giving each character’s personal action arc a sense of location and purpose. Black Widow and Hawkeye didn’t seem ludicrously out of their weight class when fighting alien robot monster things as they ought to have by rights — their “power” is just “being really good at killing things,” which is kind of a subversive thing to use as a way for people to earn their way into Captain America’s superhero team. And Whedon cracked open Iron Man’s modus operandi nearly as well as he did Cap’s in the previous film: Iron Man can almost always find a solution rather than a sacrifice, and that’s the defining characteristic of how he fights as well as how he lives.

Best of all, particularly in that magnificent CGI-aided long shot in the final battle, the fight is choreographed to depend on teamwork, with each character using the others’ unique abilities to enhance their own. Contrast it with the lame group battles involving Thor, Sif, Loki, and the Warriors Three in Thor — no comparison, is there? Visually as well as emotionally, you’ve been given a reason to value these characters as they fight the computer-generated hordes, and a reason to be impressed by their successes in doing so.

It’s also kind of a sexy movie, you know? Sexy in that stealthy, PG-13 family blockbuster kinda way, a way that reminded me of Laura Dern’s hinder in Jurassic Park kinda way. Gwyneth Paltrow’s jean shorts and bare feet, Jeremy Renner’s eminently fondleable biceps, Chris Evans’s clenching asscheeks and inverted-triangle torso as he pounds a punching bag into oblivion, Scarlett Johansson’s lovingly lingered-upon kiester, even the less physical sex appeal of RDJ and Ruffalo and Smulders…equal-opportunity hubba-hubba stuff that made the film feel alive and cut against the numbing effect of the violence. Was the fact that much of that violence, heroic and thrilling and inspiring though it may have been, was the result of an ethically dubious bureaucrat tricking its authors into perpetrating it a commentary of some sort? Sit in silence, chew on your shawarma, and decide for yourself.

The 20 Best Comics of 2011

January 1, 201220. Uncanny X-Force (Rick Remender and Jerome Opeña, Marvel): In a year when the ugliness of the superhero comics business became harder than ever to ignore, it’s fitting that the best superhero comic is about the ugliness of being a superhero. Remender uses the inherent excess of the X-men’s most extreme team to tell a tale of how solving problems through violence in fact solves nothing at all. (It has this in common with most of the best superhero comics of the past decade: Morrison/Quitely/etc. New X-Men, Bendis/Maleev Daredevil, Brubaker/Epting/etc. Captain America, Mignola/Arcudi/Fegredo/Davis Hellboy/BPRD, Kirkman/Walker/Ottley Invincible, Lewis/Leon The Winter Men…) Opeña’s Euro-cosmic art and Dean White’s twilit color palette (the great unifier for fill-in artists on the title) could handle Remender’s apocalyptic continuity mining easily, but it was in silent reflection on the weight of all this death that they were truly uncanny.

19. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen Vol. 3: Century #2: 1969 (Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill, Top Shelf/Knockabout): I’ll admit I’m somewhat surprised to be listing this here; I’ve always enjoyed this last surviving outpost of Moore’s comics career but never thought I loved it. But in this installment, Moore and O’Neill’s intrepid heroes — who’ve previously overcome Professor Moriarty, Fu Manchu, and the Martian war machine — finally succumb to their own excesses and jealousies in Swinging London, allowing a sneering occult villain to tear them apart with almost casual ease. It’s nasty, ugly, and sad, and it’s sticking with me like Moore’s best work.

18. The comics of Lisa Hanawalt (various publishers): As I put it when I saw her drawing of some kind of tree-dwelling primate wearing a multicolored hat made of three human skulls stacked on top of one another, Lisa Hanawalt has a strange imagination. And it’s a totally unpredictable one, which is what makes her comics – whether they’re reasonably straightforward movie lampoons or the extravagantly bizarre sex comic she contributed to Michael DeForge and Ryan Sands’s Thickness anthology, as dark and damp as the soil in which its earthworm ingénue must live – a highlight of any given day a new one pops up.

17. Daybreak (Brian Ralph, Drawn and Quarterly): Fort Thunder’s single most accessible offspring also proves to be its bleakest, thanks to an extended collected edition that converts a rollicking first-person zombie/post-apocalypse thriller into a troubling meditation on the power of the gaze. Future artcomics takes on this subgenre have a high bar to clear.

16. Habibi (Craig Thompson, Pantheon): It’s undermined by its central characters, who exist mainly as a hanger on which this violent, erotic, conflicted, curious, complex, endlessly inventive coat of many colors is hung. But as a pure riot of creative energy from an artist unafraid to wrestle with his demons even if the demons end up winning in the end, Habibi lives up to its ambitions as a personal epic. You could dive into its shifting sands and come up with something different every time.

15. Ganges #4 (Kevin Huizenga, Coconino/Fantagraphics): Huizenga wrings a second great book out of his everyman character’s insomnia. It’s quite simple how, really: He makes comics about things you’d never thought comics could be about, by doing things you never thought comics could do to show you them. Best of all, there’s still the sense that his best work is ahead of him, waiting like dawn in the distance.

14. The Congress of the Animals (Jim Woodring, Fantagraphics): The potential for change explored by the hapless Manhog in last year’s Weathercraft is actualized by the meandering mischief-maker Frank this time around. While I didn’t quite connect with Frank’s travails as deeply as I did with Manhog’s, the payoff still feels like a weight has been lifted from Woodring’s strange world, while the route he takes to get there is illustrated so beautifully it’s almost superhuman. It’s the happy ending he’s spent most of his career earning.

13. Mister Wonderful (Daniel Clowes, Pantheon): Speaking of happy endings an altcomix luminary has spent most of his career earning! Clowes’s contribution to the late, largely unlamented Funny Pages section of The New York Times Magazine is briefly expanded and thoroughly improved in this collected edition. Clowes reformats the broadsheet pages into landscape strips, eases off the punchlines and cliffhangers, blows individual images up to heretofore unseen scales, and walks us through a self-sabotaging doofus’s shitty night into a brighter tomorrow.

12. The comics of Gabrielle Bell (various publishers): Bell is mastering the autobiography genre; her deadpan character designs and body language make everything she says so easy to buy – not that that would be a challenge with comics as insightful as her journey into nerd culture’s beating heart, San Diego Diary, just by way of a for instance. But she’s also reinventing the autobiography genre, by sliding seamlessly into fictionalized distortions of it; her black-strewn images give a somber, thoughtful weight to any flight of fancy she throws at us. What a performance, all year long.

11. The Armed Garden and Other Stories (David B., Fantagraphics): Religious fundamentalism is a dreary, oppressive constant in its ability to bend sexuality to mania and hammer lives into weapons devoted to killing. But it has worn a thousand faces in a millennia-long carnevale procession of war and weirdness, and David B. paints portraits of three of its masks with bloody brilliance. Focusing on long-forgotten heresies and treating the most outlandish legends about them as fact, B.’s high-contrast linework sets them all alight with their own incandescent madness.

10. Too Dark to See (Julia Gfrörer, Thuban Press): It was a dark year for comics, at least for the comics that moved me the most. And no one harnessed that darkness to relatable, emotional effect better than Julia Gfrörer. Her very contemporary take on the legend of the succubus was frank and explicit in its treatment of sexuality, rigorously well-observed in its cataloguing of the spirit-sapping modern-day indignities that can feed depression and destroy relationships, and delicately, almost tenderly drawn. It’s like she held her finger to the air, sensed all the things that can make life rotten, and cast them onto the pages. She made something quite beautiful out of all that ugly.

9. The comics and pixel art of Uno Moralez (self-published on the web at unomoralez.com): What if an 8-bit NES cut-scene could kill? The digital artwork of Uno Moralez — some of it standard illustrations, some of it animated gifs, some of it full-fledged comics — shares its aesthetic with The Ring‘s videotape or Al Columbia’s Pim & Francie: a horror so cosmically black, images so unbearably wrong, that they appear to have leaked into and corrupted their very medium of transmission. Moralez fuses crosses the streams of supernatural trash from a variety of cultures — the legends and Soviet art of his native Russia, the horror and porn manga of Japan, the B-movies and horror stories of the States, the formless sensation aesthetic of the Internet itself — into a series of images that is impossible to predict in its weirdness but totally unflagging in its sense that you’d be better off if you’d never laid eyes on it. I can’t wait to see more.

8. The comics of Michael DeForge (various publishers): The last time you saw a cartoonist this good and this unique this young, you were probably reading the UT Austin student newspaper comics section and stumbling across a guy named Chris Ware. All four of DeForge’s best-ever comics — his divorced dad story in Lose #3, his shape-shifting/gender-bending erotica in Thickness #2, his self-published art-world fantasia Open Country, and his gorgeously colored body-horror webcomic Ant Comic — came out this year, none of them looking anything at all like anything you could picture before seeing your first Michael DeForge comic. It’s almost frightening to think where he’ll be five years from now, ten years from now…or even just this time next year.

7. The comics and art of Jonny Negron (various publishers): What if someone took Christina Hendricks’s walk across the parking lot and trip to the bathroom in Drive and made an entire comics career out of them? That is an enormously facile and reductive way to describe the disturbing, stylish, sexy, singular work of Jonny Negron, the breakout cartoonist of the year, but it at least points you in the right direction. No one’s ever thought to combine his muscular yet curiously dispassionate bullet-time approach to action and violence, his Yokoyama-esque spatial geometry, his attention to retrofuturistic fashion and style, his obvious love of the female body in all its shapes and sizes, and his ambient Lynchian terror; even if they had, it’d be tough to conceive of anyone building up his remarkable body of work in such a short period of time. Open up your Tumblr dashboard or crack an anthology (Thickness, Mould Map, Study Group, Smoke Signal, Negron and Jesse Balmer’s own Chameleon), and chances are good that Negron was the weirdest, best, most coldly beautiful thing in it. It’s like a raw, pure transmission from a fascinating brain.