Posts Tagged ‘dalton’

085. The Baseball Player

March 26, 2019On a warm summer’s eve

In a bar down in Jasper

I saw “The Baseball Player”

Ersatz vintage, prob’ly cheap

Frank Tilghman was a-starin’

Out the window at the rumble

When Morgan overdid it

Then he began to speak

He said, “Son, I’ve made a life

Out of hurtin’ people’s livers

Knowin’ not to card ’em

By the way they held their eyes

And I heard that you’ll be stayin’

Out with Emmett by the river

Have a taste of my whiskey

And give me some advice”

So he handed me a bottle

And he ogled as I swallowed

Then I smoked a cigarette

And glistened in the light

And the night got deathly quiet

And his face made weird expressions

I said, “If I’m gonna be your cooler

I’m gonna be your cooler right

You’ve got to know when to hold it

Know your opponent

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

Every cooler knows

That the secret to survivin’

Is knowin’ which guy’s throats to rip

And knowin’ who to kick

‘Cause no one is a winner

And every fight’s a loser

Go ahead and call me dickless

But I sure won’t show my dick”

And when I finished speakin’

I turned back toward the window

Crushed out my cigarette

And wandered to my Benz

And somewhere in his office

Frank Tilghman stood there grinnin’

Then doctored dirty words

In the graffiti in the Men’s

You’ve got to know when to hold it

Know your opponent

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

You’ve got to know when to hold it (when to hold it)

Know your opponent (your opponent)

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

You’ve got to know when to hold it

Know your opponent

Know when it’s time for nice

And know when it’s not

You’re gonna pay me money

To drive a man’s face through a table

Cuz it’s my way or the highway

I’m extremely hot

084. Honesty

March 25, 2019Emmett is Dalton’s landlord. He rents him an apartment constructed out of the loft in his barn. It’s open to the outside and has no TV or telephone or “conditioned air,” which Emmett explains is why no one wanted to rent it from him, not even for the price of $100 a month, which he seems willing to be talked down from anyway. It is a preposterously well-designed living space to be owned and operated by Emmett. If he can afford to have it built and to rent it for a song, he probably has enough money socked away somewhere to give his neighbor Brad Wesley a run for his money in the real estate, liquor distribution, mall development, JC Penney franchising, and goonery businesses alike. But we’ll take his self-presentation as a crusty but kindly old coot at face value for the purposes of this essay, which concerns an entirely different (I think) curio about the character.

When Dalton first arrives at his ranch to inquire about the “room to rent,” Emmett’s affect is wary and his response monosyllabic. He’s a far cry from the guy who, about a minute and a half later, will kvetch about Brad Wesley to this total stranger and then tell him “callin’ me ‘sir’ is like puttin’ an elevator in an outhouse—it don’t belong.” Farther still from that affable man with his colorfully dumb similes is the Emmett we witness on the stairs up to the apartment in between.

“You honest?” he asks Dalton.

“Yessir,” Dalton responds like the good boy he is.

“You expect me to believe that?” Emmett replies. Get it? Because he asked him if he was honest, but if he doesn’t know the answer to that already he wouldn’t know if he was lying in reply, hence the follow-up inquiry, haha, how droll.

Dalton thinks it’s funny too. “No sir,” he says, smiling and laughing and warming to the old man.

Only here’s the thing: There’s no indication from Emmett’s tone of voice, facial expression, or body language that he’s kidding at all. He pretty much freezes and LOOKS DALTON DEAD IN THE EYE during the ostensible punchline part of the exchange. Without knowing anything else about Emmett, you’d think he’s dead fucking serious about wanting to know if Dalton is really being honest when he says he’s honest. He could launch into a “What do you mean I’m funny” routine right there, that’s how intense it sounds.

Then Brad Wesley buzzes his horses with a helicopter and the thaw begins. Before long we have the Emmett we’ll have for the rest of the film—a guy who drops corny jus’ folks wisecracks and aphorisms with a straight face and then immediately loosens up, letting Dalton and company in on the joke. He ribs Dalton immediately after Dalton saves him from the burning wreckage of his own firebombed house by movie’s end.

What’s going on here, then? I have a theory, and don’t I always. Emmett is a servant of the Secret Fire, Wielder of the Flame of Anor. He’s Major Briggs, he’s the Log Lady, he is of the White. Not himself a spirit, he is nonetheless their tool, their agent, sent to Jasper and instructed, Noah-like, to build a fancy schmancy loft and wait for the indwelling. To him shall come a stranger, one who will make the wrong things right. How will I know him, Emmett asks the glowing voice, and that voice replies You will test him with paradox, the language of the righteous. Then and only then will you recognize him as a traveler on the Dalton Path.

You honest/you expect me to believe that. Be nice/until it’s time to not be nice. Yin/yang. The White Lodge and the Black.

082. Intimacy

March 23, 2019If there’s one thing the Marvel/Netflix shows, even the ones I’m not crazy about, have been good at, it’s tying their superhero/vigilante violence to moments of physical intimacy. Sometimes this involves the main characters having sex, and from Jessica Jones and Luke Cage to Luke Cage and Misty Knight to Matt Murdock and Elektra Natchios, those scenes have been hot across the board. That’s certainly true on this show as well, from Agent Madani and Billy Russo to David “Micro” Lieberman and his wife Sarah to [the Punisher] and Beth the bartender just last episode.

At other times the violence itself is intimate. This naturally tends to be the case more for the characters who lack super-strength than for those who do, but it’s true. Watching mortal men like Matt Murdock and Frank Castle be made vulnerable by the infliction of violence on their bodies is a display of intimacy. To quote myself quoting Barbara Kruger regarding another show, “You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men.” Hallway fights are an intricate ritual indeed.

And then there are the moments of triage that occur after the battle is over. I’m thinking Luke Cage tending to Misty Knight’s mangled arm for damn near an entire episode (overlong thanks to Netflix Bloat, but still notable), or Frank Castle and Karen Page leaning into each other in an elevator after spending an entire episode trying to avoid being murdered by a mentally ill gunman. In this case it’s “Rachel” (if that is her real name), the shifty fugitive Frank’s been protecting for two episodes, removing a slug from Frank’s right buttcheek. Earlier in the episode, it’s her taking his boot off for him when he proves unable to do it himself. You see the same principle at work when Daniel Craig hugs a crying Eva Green in the shower after a killing spree in Casino Royale, or when Bruce Willis has a heart to heart with Reginald Vel Johnson while he picks shards of glass out of his bare feet in Die Hard, or even when Patrick Swayze and Kelly Lynch meet cute while she staples a knife wound in his side in my beloved Road House. Sylvester Stallone, the actor who at his best most reminds me of what Jon Bernthal does, constructed two entire franchises around the idea that there’s something interesting about watching his perfect body get beaten to shit. Moments like this make the violence real and draw those of us who’ve never experienced such combat into the moment by reminding us we all share the same basic physical vehicle for navigating the world around us.

When I went searching for this quote I’d forgotten all about including Road House as an example of the tendency I’m discussing, but there you have it. The first thing Dr. Elizabeth Clay does with Dalton, after ribbing him for having gotten the shit kicked out of him over and over for years, is staple shut the gash in his side. She’s up close and personal for this, face inches away from armpit and chest hair and nipple. Often she looks up and grins at him, and if you’ve ever seen the phrase “slow smile” used in reference to a sexy person in a book and want an illustration of the concept, you’ve got one. I’m sure I don’t need to underline what the relative positioning of their heads suggests. I mean, this is a person who meets the man she will fall in love with for the first time when he’s shirtless and waiting for her to touch and heal his body. At this point she’s never seen him with a shirt. (Start as you mean to go on, I suppose.) And in the reverse, Dalton first sees the woman he’ll fall in love with when she’s approaching him to inject him with a needle and fire metal staples into his knife wound, a fate to which he stoically submits, other than that he rejects the needle and the dose of anesthesia that comes with it for reasons described in the title of this essay series.

To say that all of this supercharges their subsequent interactions with erotic intimacy is to understate the case considerably. I know people have mixed feelings about their sex scene but if you can watch their first couple of dates without wanting them to bang instantly you’re a stronger person than I am. It all begins here. So does the sexualization of Dalton’s mentor Wade Garrett, whose chemistry with the Doc is phosphorescent and who exposes his pubic hair to her in the course of revealing a scar given to him by a woman as part of their getting-to-know-you evening out as a threesome. I think there are even echoes, faint but audible, of the way Elizabeth looks at Dalton during this scene in how various men who either want to or will commit violence against Dalton look at him as well. When they finally do battle, Jimmy in particular will sexualize that violence.

Considering how resolutely un-sexy most of the bouncer-goon combat is in this film, to inject this pain-pleasure connection into the proceedings and have it pay off frequently moving forward is a minor miracle. Most action movies of the period were content with the corniest, fanserviciest, most sexist, least interesting ways of depicting sex. Road House has some thoughts in its head after all, and they’re kind of dirty.

080. Dodge

March 21, 2019

If there’s anything else in the history of action cinema I’ve studied with the same open-hearted intensity I’ve applied to Road House, it’s the Tomb of Balin/Bridge of Khazad-dûm sequence from Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Back in the summer of 2001, in the Before Times, I was invited by New Line Cinema in my capacity as assistant editor of the Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly, my first real job out of college (see what I mean about the Before Times?) to watch the 20 minutes or so of footage from Jackson’s first Lord of the Rings movie that had been publicly screened, initially some weeks prior at the Cannes Film Festival. Wisely the studio had selected the film’s first real action setpiece, the slobberknocker with the orcs and the cave troll in Balin’s Tomb and the flight down the crumbling staircase afterwards. Any doubts I might have harbored about the ability of Jackson, a filmmaker whom I loved for Heavenly Creatures but wasn’t sure could tamp down his manic style for Tolkien’s world, evaporated the moment the fighting began. This was a director who understood that effective action is shaped by the environment in which it’s staged, with easily understandable physical stakes for the success and failure of each blow and maneuver, relayed through camerawork that allows the eye to parse the spatial relationships between the combatants.

What’s more, and the friend I brought along with me as my plus-one to the screening room is the one who pointed this out, Jackson understood that the key to fantasy as a genre is scale, intuiting George R.R. Martin’s much-quoted dictum that we turn to fantasy “to find the colors again,” to transcend drab reality on (paraphrasing here) the wings of Icarus rather than Southwest Airlines. Neither Jackson nor Martin (nor Tolkien, nor Benioff & Weiss for that matter) felt this meant completely detaching the material from reality; on the contrary, the punishing realism of Martin’s setting and the painstaking detail of the Weta Workshop’s worldbuilding made the truly massive scope of the landmarks and lives of Westeros and Middle-earth all the more convincing.

I’ve told this story many times now, but it was specifically one of the Moria sequence’s action beats that brought this home to me. As the Fellowship flees down those gigantic, precarious stairs, orcs begin pelting them with arrows. Legolas, the Elven archer, turns and fires back at one of the distant foes. The camera travels as if mounted on the shaft, giving us an arrow’s eye view of the cave and the evil creature on the opposite end towards whom it is racing. A cut at the moment of impact switches us to a view of the same cavern from just behind and above the orc (by now struck right between the eyes and plummeting into the abyss below), angled downward toward the Fellowship on the stairs hundreds of yards away. The arrow’s flight, and our flight along with it, describes that vast space in a way a more traditional establishing shot could not. If we’d started with that over-the-shoulder shot looking down at the Fellowship we’d have gotten the picture I suppose, but we wouldn’t have been made to feel the space, the scale, the awe.

Whether to reserve the sight of the Balrog for the eventual filmgoing public or because that sight had not yet been completed I can’t recall, but the preview cut off with our final glimpse of the Fellowship escaping the stairs. The chase across the Bridge, the standoff between Gandalf and the Balrog, Gandalf’s triumph and fall, and the Fellowship’s mournful escape had to wait until the premiere. But there’s another moment with an arrow that stuck with me then and still does today. As Aragorn, the last one out of the Mines, looks back at the chasm, the rain of arrows from the orcs, who’d given the Balrog a wide berth, resumes. Viggo Mortensen, an amazing proficient action performer for a guy who had about a week of instruction before his first on-camera swordfight compared to the rest of the cast’s extensive training camp, had clearly been instructed by Jackson to act as though he was dodging arrows that were added digitally after the fact. Like a particularly generous pro wrestler he sold the hell out of it, at one point ducking so dramatically it’s like he was avoiding some big galoot’s haymaker. The desultory choreography of the move jumps out at me because Mortensen’s Aragorn is otherwise a model of physical efficiency in his fighting style, as befits a man who’s been hunted all his life and has learned that excess movement can mean the difference from ending a fight merely exhausted and ending a fight dead. It’s taken me time to come around to it but I now recognize it as the right approach for a character who’s been momentarily poleaxed by a grief he never believed he’d experience.

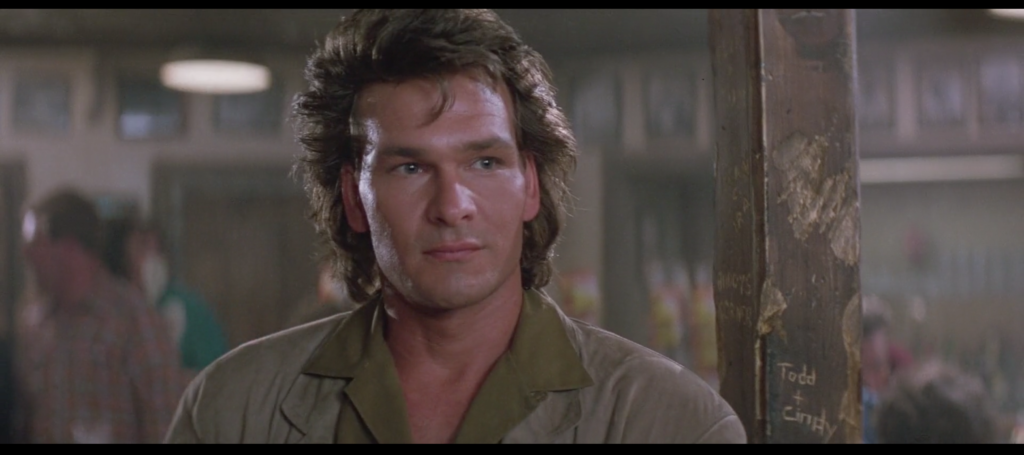

Anyway, at one point during the big bar-destroying fight that breaks out in Road House when a man squeezes another man’s wife’s tits without paying to kiss them as he’d appeared to agree to do, a stray bottle comes flying in Dalton’s direction and shatters against the post next to which he’s been standing and taking in the scene, and he dodges it and resumes watching in less time than it took either of the arrows described above to do their thing. This doesn’t tell us anything about the scale of the Double Deuce, the spatial relationship between Dalton and the unseen bottle-thrower, the nature of the world in which the film takes place, the emotional state of the characters, or the approach of director Rowdy Herrington toward the material. It just tells us that Dalton is so good at dodging broken glass that it doesn’t even disturb his spit-curl. And that’s all you need to know, son.

079. Son

March 20, 2019O’Connor is the cornucopia of plenty of goons. Like Barry White, He’s Got So Much To Give, and like Barry White he gives it in basso profundo to boot. In addition to delivering the purest expression of contempt I’ve ever heard in cinema, in addition to getting beaten unconscious when his boss finds his excessive bleeding to be an indicator of cowardice, in addition to dressing business-cazh to every ass-kicking he attempts to give and/or winds up receiving, this poor dumb bastard somehow drills right down into the subtext of Road House and strikes black gold without even trying. My partner, the cartoonist Julia Gfrörer, told me earlier on in this process that Road House is a movie about fatherless sons and sonless fathers. And what do you know—O’Connor addresses Dalton accordingly. When he appears in the Double Deuce with Tinker and Pat McGurn to force Tilghman to re-hire the mustachioed failnephew as a bartender or face the cessation of liquor shipments, Dalton is naturally initially curious as to their intentions. After shutting up the shithead, O’Connor grins broadly and tells Dalton “Mr. Tilghman has changed his mind,” then lowers his head and looks the cooler dead in the eye and gets all serious and adds “And that’s all you need to know, son.”

Son! For context, please note that Michael Rider, the actor who plays O’Connor, is just over four months older than Patrick Swayze. Not even years, which would be goofy enough—April 1952 vs. August 1952 is what we’re talking about here. “Son” is an attempt to bigfoot Dalton by a man who believes himself to be an authority figure. It’s likely meant to belittle him, and I mean literally: Dalton is just knee-high to this towering would-be father. It’s meant to son him, in the Nicki Minaj “all these bitches is my sons” sense.

Naturally, it works out about as well for O’Connor as anything else he tries in this movie. But it does earn him this distinction: He is the only man murdered by Dalton who casts his own eventual demise in Oedipal terms. No doubt Laius was a bleeder too.

078. Morning bed

March 19, 2019When Carrie Ann shows up at Emmett’s farm to visit Dalton the night after he fires Morgan and Pat McGurn and puts a Knife Nerd’s face through a table <exhale> this is the sight that first greets her. Not Dalton nude, and not Dalton half-dressed and stretching and smoking and somehow hung over from reading too hard the night before—just a man, beautifully centered, in a bed, beautifully centered, in a room with hardwood floors and floor-to-ceiling windows, glowing with natural morning light reflected off the waterfront view outside. It’s just ridiculous, for a movie this dumb, to have a shot this pretty with light this lovely. It’s like Barry Lyndon up in here, for real.

But it’s also the one moment during which I can kind of sort of imagine being Dalton. Not fighting people for a living, no. Certainly not fighting people and winning for a living. Not parading around nude in front of my coworker. Not smoking and stretching, simultaneously, first thing after I roll out of bed. Not doing either thing separately either. Not grabbing another Jim Harrison novel while murmuring “Hair of the dog that bit me” or whatever the appropriate response is to getting a hangover from reading Legends of the Fall might be. Not pissing off foundational figures in the hardcore wrestling, Los Angeles punk, and John Cassavetes acting scenes in one fell swoop. Not giving goofy little salutes to people as we say our goodbyes. Not commanding a $350K salary. Not having sex with a doctor of nebulous speciality played by Kelly Lynch, though I suppose not not doing that either. Not accepting any offer made to me by any character played by Kevin Tighe. Not festooning the mansion of a mall developer with corpses, unless perhaps they really deserved it. None of that. But sleeping in a beautiful gray-bright wooden room on the water, naked under the covers, groaning a bit as I get up but then looking around and seeing that the place I live in feels warm and inviting and special and a place like I might be happy to live in? Yeah, I can imagine that.

077. Doorway to Doc

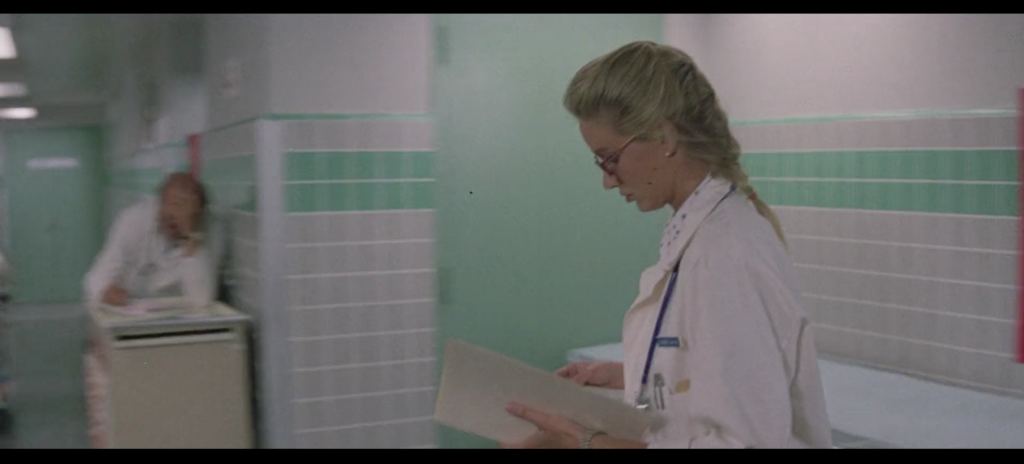

March 18, 2019Slashed with a knife and socked in the face by Tinker, propelled through a broken window and onto the floor in order to shake the grasp of O’Connor, dispatching both O’Connor and Pat McGurn in short order while his coworkers take Tinker down, Dalton is done with the Double Deuce for the night. I suppose when you’re pulling down a solid six figgies to make sure a Missouri bar with an unpaved parking lot isn’t overrun by concussed hayseeds who’ll stab anyone who fails to laugh at “if I said you had a beautiful body, would you hold it against me” you can make your own hours. Love what you do and you’ll never work a day in your life, etc. So out Dalton goes, through a back door into a vaguely defined sea-green area on the other side, the bright crimson stain on his torn shirt traveling with him.

Working late in the trauma unit, Dr. Elizabeth Clay walks across the hospital hall, browsing a patient’s medical file. For a split second we catch a glimpse of a bright red wall-mounted case, for a fire extinguisher perhaps, or some kind of emergency medical device. Professional and presentable, hair in a tight French braid, face half-covered by enormous glasses that make her look as if she’s viewing the entire world on an x-ray readout, she’s a world apart from Dalton, the sweaty, bloody, disheveled man whose (latest) knife wound she’s about to staple shut.

Yet she isn’t, is she a world apart, is she? She is connected, via not-quite-but-close-enough match on action editing, directly to Dalton via his exit through the Double Deuce’s back door. Her movement picks up almost where his leaves off, with just enough of a hiccup to keep it from reading as cutesy. He walks right out of the Double Deuce and into the Doctor’s life. The Doc takes his cinematic arrival literally in stride, like she’d been walking with him all along.

076. Foxworthy

March 17, 2019This fellow right here I call Foxworthy, for obvious reasons.

Now our man Foxworthy stands out in a crowd, even in a wretched hive of scum and villainy like the pre-Daltonate Double Deuce. For starters, he looks like a very famous comedian who within a few short years of the events of Road House will no doubt siphon up some of the spending cash freed up by the expulsion of several Double Deuce patrons. Aside from the lovely perms sported by the two other guys in the Jeff Healey Band and Dalton himself, he’s the only man in there for whom hair seems to have been anything more than an afterthought; “business up front, party in the back” is not an arrangement arrived at without some consultation with one’s barber. The mustache sets him apart as well, particularly when compared to the sorry situation taking place on the upper lip of Pat McGurn. Finally, at least where his appearance is concerned, he is wearing a bright red t-shirt, making him easily the loudest splash of color in the entire barroom. This isn’t because he plays a major role or has an actual speaking part or threatens someone with a knife over his table-dancing girlfriend or anything—as best I can tell it’s just because the costume department couldn’t be bothered to keep track of who was popping and who wasn’t.

But he mostly stands out because he grabs poor wonderful Carrie Ann by the waist and tugs her bodily towards him, spilling her drink tray and nearly getting punched in the face by her for it. Dalton sees this plain as day, as it’s one of the first incidents he comes across when he enters the Double Deuce for the first time. But his role at that point is simply one of observer. He intervenes no more than, say, Hank, who’s leaning against a pole a few feet away, perhaps thinking over his instructions from Horny Steve not to intervene in the fight erupting in the billiards area at approximately the same time. While like most of the early barflies Foxworthy simply disappears when Dalton starts cleaning the place up, he more than most deserves some kind of comeuppance for his transgression against Carrie Ann. Were it to have taken place just one week later probably would have earned his face an all-expenses-paid trip through a table. But Dalton’s non-intervention here establishes that, in his own later words, “It’s a job. It’s nothing personal.” Dalton will have occasion to break his own guideline in this respect many times over by the time the film is through, but for now, Foxworthy has no idea what kind of bullet he just dodged. You might say Foxworthy is unworthy.

073. Lebowski II: Garden Parties (continued)

March 14, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a shady business mogul played by Ben Gazzara flouts decency standards in a waterfront community that he controls through a combination of extravagant wealth and muscular morons. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film in which Gazzara reprises this role.

The two orgiastic parties thrown by the Gazzara characters in these movies, Malibu pornographer Jackie Treehorn in the latter and Jasper JC Penney enthusiast Brad Wesley in the latter, have so many surface-level similarities it remains difficult for me to believe that Joel and Ethan Coen were not familiar with Rowdy Herrington’s masterpiece when they made their own. Smiling men tossing topless women through the air, the bright blue of a pool juxtaposed against the dark of the night, a general “the night time is the right time” atmosphere, the dramatic entrance of the Gazzara characters themselves, goons—it’s all there.

Yet the differences reveal much, as they typically do, even as they point to how similarly the two films often function. I vividly remember going to see Lebowski at the movie theater when it debuted and finding it a sensational film, in the sense that on a scene-by-scene basis I felt buffeted by new and unprecedented forms of ridiculousness. The Treehorn beach party is way way up there on the list, beginning as it does with a topless woman plummeting through a void with the otherworldly voice of Yma Sumac blasting at full volume. This is the impression Treehorn wished to make on the Dude as well, whom he used his goons to summon to his estate, impressed with the excess and splendor of his lifestyle, lulled into a false sense of security, drugged, and dumped in the street. It was a party for himself and his, I dunno, friends I guess?, but it was also a performance for one Jeffrey Lebowski. Treehorn’s direct-address introduction of himself right into the camera speaks to that.

Brad Wesley’s idiotically raunchy shindig has no such purpose. He and his men and women have no idea Dalton is watching from across the river; indeed it’s unclear if at this point in the film Wesley has any idea where he lives at all, and furthermore Dalton makes an effort to hide his observation of the party by switching off the light by which he was reading a Jim Harrison novel when the noise of the soiree first distracted him. Additionally there is nothing particularly disorienting or otherworldly about this parade of gawping meatheads and Mötley Crüe video extras—they simply run out of Wesley’s house in a surprisingly orderly line, start stripping off their clothes (“hot babe” bikinis for the women, the usual thug-casual style for the goons), and boogie down to Bob Seger’s “Monday Morning” of all things. Wesley arrives last but he incorporates himself into the festivities rather than set himself apart, joining his girlfriend Denise and pinching the cheek of Mountain, his tallest and goofiest goon. Where the Dude is duly impressed by Treehorn’s milieu (“Completely unspoiled!”), Dalton is merely amused by Wesley’s, a fair and perhaps even generous reaction to a party at which a central component is Terry Funk with his pants around his ankles.

The point I’m trying to make is that while the Ben Gazzara party scene in The Big Lebowski serves a concrete purpose for the Ben Gazzara character, the Ben Gazzara party scene in Road House exists simply to entertain an audience the film presumes to be pretty stupid, or at least open to enjoying pretty stupid things. Dalton, a man of diverse interests, enjoys it just fine. Thus Wesley’s power to impress and intimidate Dalton with his Dionysian powers is dissipated. When he finally does attempt to bowl the cooler over with demonstrative partying and sexuality deep into the film, when he has Denise strip at the Double Deuce as a show of masculine force, Dalton is completely impervious. This party is a vaccine.

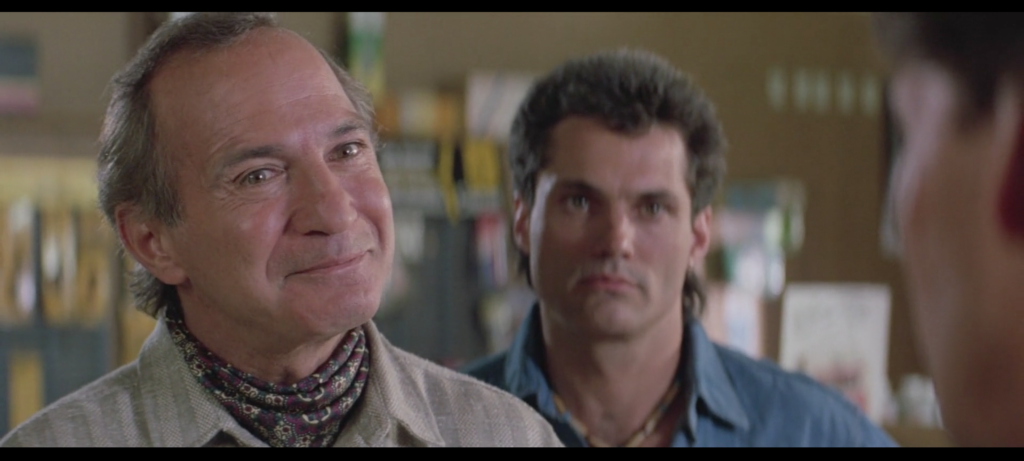

070. Face to face

March 11, 2019

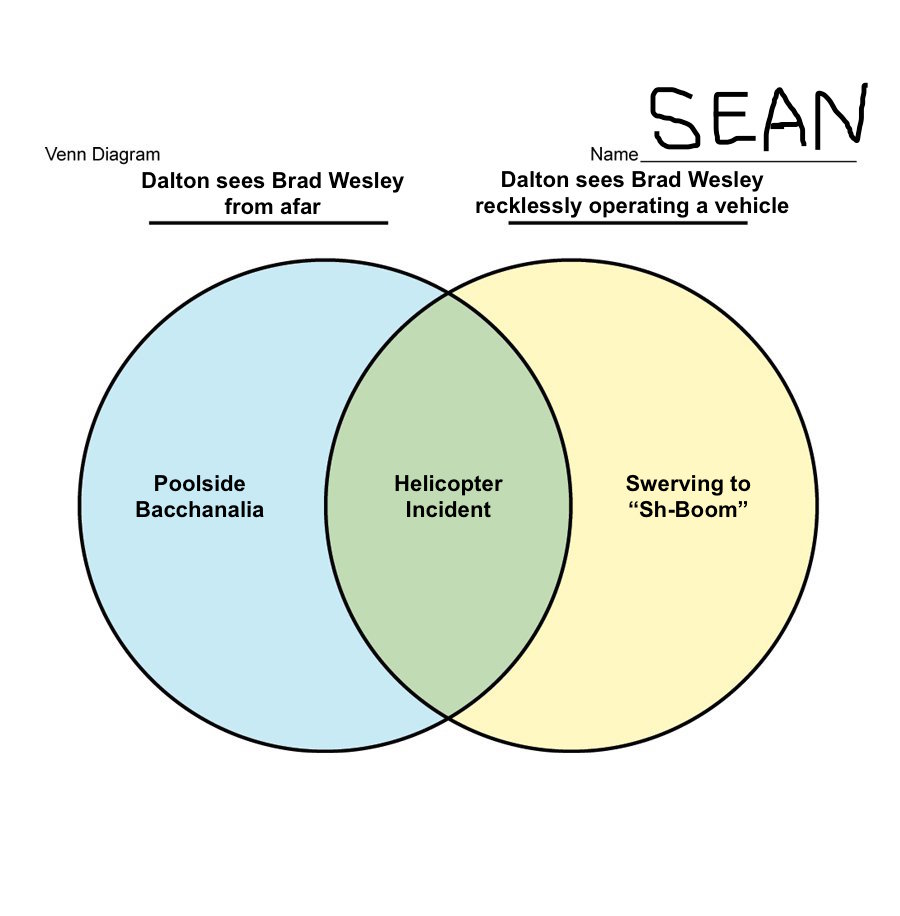

This is not the first glimpse of Brad Wesley that Dalton has gotten. Since arriving in Jasper, Dalton has seen Brad Wesley twice from afar, first when Wesley’s helicopter buzzes Emmett’s horses, later when he watches Wesley’s poolside bacchanalia from across the river. Dalton has also seen Brad Wesley twice while recklessly operating vehicles, first the helicopter incident and then when Wesley nearly runs him off the side of the road as he swerves back and forth singing “Sh-Boom.” Here’s a Venn diagram to help you keep track.

But their encounter inside Red Webster’s auto parts store the day Dalton visits to buy what he needs to repair his vandalized car is the first time Dalton and Brad Wesley meet face to face. No sparks fly. No cutting words are exchanged. They don’t even shoot each other dirty looks, though Red sure is unhappy to see Wesley and Wesley’s bastard son (source for this claim?) Jimmy stares at Dalton like he’s a starving man and Dalton is a steak he’s really mad at for some reason.

No, it’s all smiles and handshakes when these future nemeses first meet. Wesley exchanges his hand and introduces himself, Dalton takes it and returns the favor. Red even goes so far as to explain to Wesley that “He’s working at the Double Deuce,” though whether to subtly impress upon the nefarious businessman that the bar will no longer be easy pickings for him or to simply make smalltalk with a man with whom he’s forced to be cordial is anyone’s guess. “Oh, terrific, hope you’re gonna clean that place up!” Wesley enthusiastically croaks. “Bad element over there. Well, anything that I can do for you….” Later that day Wesley will send Tinker, O’Connor, and Pat McGurn to the Double Deuce, and two of those men will attempt to murder Dalton at knifepoint. For now Dalton simply returns Wesley’s friendly grin, thanks Red for the aerial, and meets Jimmy’s steely gaze as he exits the place.

If you’ve read seventy essays about Road House in seventy days you know enough about Dalton to know he hasn’t been snowed by this dude. For one thing there are his previous three first impressions of the man, none of them good. For another it’d be hard to miss the way Red tenses up when Wesley walks in, or the fact that Wesley travels to the auto parts store with a dead-eyed denim-clad psycho who looks like he came home from ‘Nam with one of them funny necklaces. Indeed it seems fair to assume that the reason Dalton performs tai chi by the riverside while glistening with sweat later that afternoon is to shake the spiritual residue left behind by Wesley (who watches him from afar this time, chuckling to himself with amusement). No, Dalton’s cooler-sense is tingling, you can bet on it.

But Red Webster’s auto supply store is a place of dreams, a nexus, if you will, of realities that are and were and yet may be. Is it so hard to imagine a world in which this handshake, these smiles, are the sum total of the interactions between these two men? A world at peace, in which the war between Dalton and Brad Wesley never takes place, where countless limbs go unbroken, where multiple homes and businesses are never destroyed by explosives or monster trucks, where no one dies so that the new Double Deuce might live?

069. The Third Rule, Verse 3

March 10, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, once more, is the third.

3. Be nice. (continued)

We’ve established the Third Rule’s Great Commandment, and we’ve examined its combination of theory and praxis. Today’s lesson follows closely in the latter’s footsteps. Almost literally, insofar as it’s about walking.

You’ll recall that the previous lesson introduced the parable of the man who gets in your face and calls you a cocksucker. In the lines that follow, Dalton continues the story. “Ask him to walk,” he advises his bouncers regarding such a person, “but be nice. If he won’t walk, walk him, but be nice. If you can’t walk him, one of the others will help you, and you’ll both be nice.”

By now his voice is pleasant, almost cheerful, the “it’s my way or the highway” edge to it long gone. It stands to reason, since the whole point of this passage is that neither he nor anyone else need walk his way alone. You can do so side by side, arm in arm, perhaps even hand in hand. Indeed his delicate double-handed gesture when he says “and you’ll both be nice” suggests nothing so much as a pair of children playing “Heart and Soul” together on the piano in the school music room.

This is the least difficult portion of the rules so far from which to glean the hidden moral instruction beneath the practical element. By way of comparison, eep in mind that “turn the other cheek” was as literal as it gets, at least within the context of the sentence in which Jesus introduced the concept: You get socked in the side of the face, you offer up the other side too. Yet hundreds of millions of people over thousands of years had no trouble figuring out what he was getting at.

I’d like to think that Jack, Hank, and Younger understand that Dalton is talking about more than just the problem introduced by Hank at the start of the Giving of the Rules: “A lot of the guys who come in here, we can’t handle one-on-one, even two-on-one.” Aiding a fellow bouncer in the ejection of a particularly recalcitrant or powerful patron is important. Even reiterating that the purpose of bouncing is to bounce the patron out of the bar, not bounce his head off of it, is important. But is “If he won’t walk, walk him,” so far removed from “it was then that I carried you”? Is “one of the others will help you” so different from “For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them”? Seeing yourself as part of a whole that includes the patrons, the bouncers, and the bar—that is the key that unlocks the new Double Deuce, the nice Double Deuce, a house with many mansions. When you walk through the storm, hold your head up high, and don’t be afraid of the dark.

068. “Opinions vary.”

March 9, 2019Morgan: “You know, I heard you had balls big enough to come in a dump truck, but uhh…you don’t look like much to me.”

Dalton: “Opinions vary.”

Morgan: […]

Morgan does not have the right temperament for the trade, but he does know a threat when he sees one. To a fault, perhaps. His biggest fault as a bouncer, aside from working for the local crimelord, is that he exists in a permanent state of bouncing. To Morgan, every customer is a peckerhead who’s been slugged in the gut and physically thrown through the front doors into the parking lot—they just don’t know it yet. Morgan’s great task in life is to be the one to inform them, with his fists. Witness the first thing he says to Dalton: “And if you’re not drinkin’, you’re outta here.” This is just after he ejected Mister Nipple to Nipple, and in the process upended a table and sent several perfectly pliant patrons of the establishment ass over elbows to the ground. You’d think he’d have bigger fish to fry, but no: The silent stranger with the magnificent head of hair is another threat waiting to be neutralized. Morgan is a preemptive strike in a sleeveless green t-shirt. Existing in this state of constant certitude—that everyone’s an asshole but you, and that it’s your job to pound that knowledge into them—makes Morgan ill-prepared to brook even the slightest dissent.

Witness the above exchange after Dalton’s first night visiting the Double Deuce. Morgan has just participated in a bar-wide fight that leveled nearly everyone and everything in its path; Dalton sat the whole thing out, observing from a distance and then meeting in Tilghman’s office for an off-screen tête-à-tête. So perhaps Morgan’s skepticism about Dalton’s martial prowess is warranted, though expressed it a needlessly condescending way.

To his credit, Dalton doesn’t even disagree with him, not explicitly. He neither confirms nor denies whether his balls are big enough to come in a dump truck, or whether he looks like much, or whether he is much. All he says is “Opinions vary,” and that’s enough to transform Morgan’s whole affect to a comical degree. (Terry Funk is a perform accustomed to playing to the cheap seats, after all.) He goes from a smirking prick to a puppy who just heard “Bad dog!” within about one second, all because Dalton suggested that points of view exist besides Morgan’s own. That’s it, that’s all it takes. If Dalton had walked right up and cold-cocked him it would have had less of an impact.

Aside from Dalton and Wade Garrett themselves, Morgan is by all appearances the most experienced bouncer in the film. Not for him, the Dalton Path. Not for Morgan, the Way of Wade Garrett. The Morgan Idea holds that Morgan is the master of everything and decides everything. Dalton’s simple statement that this is not so strikes at the man’s very soul; by resisting he has signed his own death warrant. That dump truck is barreling down the road toward him at 100 miles an hour, loaded for bear with Dalton’s balls, and he is constitutionally incapable of getting out of the way until he kisses the grill.

067. Table dancer

March 8, 2019“We don’t cause trouble, we don’t bother nobody.” Few of the barflies whose acquaintance either we or the staff of the Double Deuce have the good and/or mis fortune of meeting adhere to Rick the Ruler’s public proclamation of good behavior as closely as Table Dancer. Played by Sylvia Baker, she’s the character who dances on a table. Here are things that, based on the conduct of other barflies in the film, she could reasonably be expected to do instead:

- Pull a knife and threaten to stab someone at a moment’s notice

- Pull a knife and attempt to stab someone at a moment’s notice

- Pull a knife and actually stab someone at a moment’s notice

- Agree to grope a woman’s breasts for money without actually having the money

- Wallop the shit out of someone who groped a woman’s breasts for money without actually having the money

- Offer her breasts to be groped for money without first doing due diligence

- Have a fistfight on the floor with a sibling

- Propose getting nipple to nipple

- Lob a beer bottle at a blind man’s head because he says he has to urinate

- Laugh like an imbecile

- Drink until incapacitated

- Have sex with an employee in the storeroom

- Be part of a team sent by a local businessman to assassinate a bouncer

- Not wear a shirt

- Purchase and snort cocaine, though somehow not in that order

- Deface the walls with vulgar graffiti

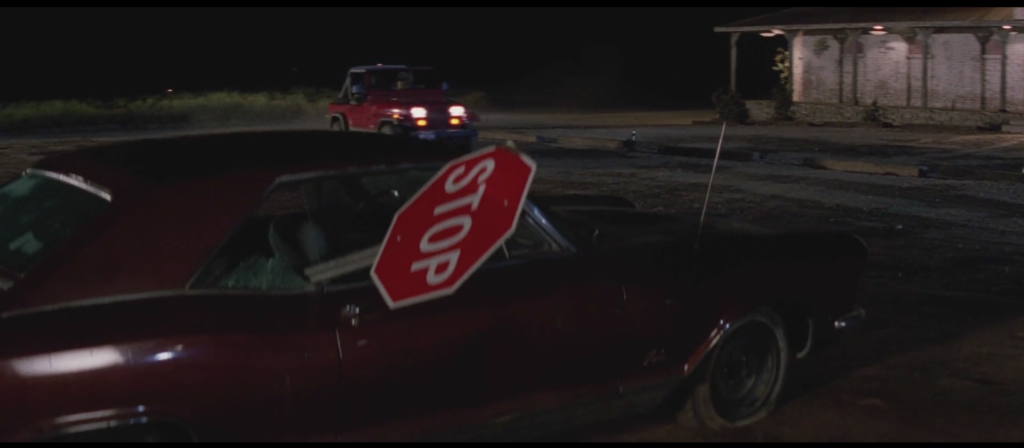

- Locate the vehicle of a bouncer, slash all its tires, break its radio antenna, smash its windshield, and shove an entire stop sign through the window

- Say “dirtball” or “moose-lips”

- Wear a very loud shirt

All Table Dancer wants to do is gyrate spasmodically on a table to the Jeff Healey Band, occasionally lifting her skirt to show that her silver-black bodysuit goes all the way down. It’s her rat-faced boyfriend who decides this is worth committing murder in a room full of witnesses for, not her. She doesn’t even get upset when Dalton rams her boyfriend’s skull through furniture solid and steady enough for her to dance on. She’s just like “Oh! Party’s over I guess” and takes Dalton’s extended hand to climb down off the table, then looks him over like the snack he is as she leaves.

Table Dancer represents the joie de vivre to which the rest of the film’s barflies should aspire. Would Dalton have been so quick to send Hank in to break up the party if this were the worst of the behavior one could expect of the Double Deuce’s clientele? I think not. She falls victim to broken-windows policing more than anything else, like how Giuliani used to shut down all the clubs where black people went to listen to hip-hop to make the city safe for oligarchs, somehow. Am I saying Dalton gentrified and Disneyfied the Double Deuce?

Am I?

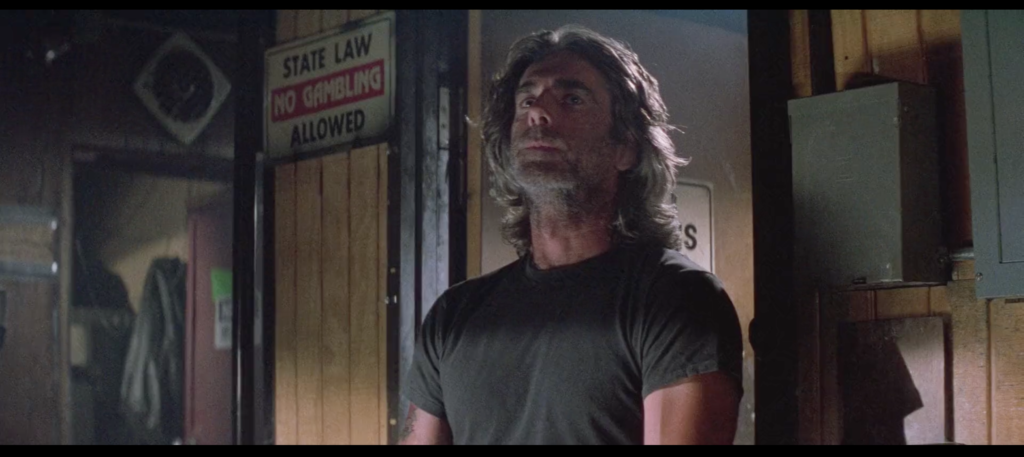

066. Frank Tilghman’s fist

March 7, 2019One thing I never noticed before starting this project, one thing I never noticed before tonight in fact, one thing I never noticed despite watching Road House dozens of times over the course of nearly fifteen years, is that when Brad Wesley’s goofiest goons, Tinker and O’Connor, come to the Double Deuce with Wesley’s nephew Pat McGurn to force Frank Tilghman to overrule Dalton’s decision to fire Pat under threat of physical harm and the cessation of liquor shipments to the bar due to Wesley’s control over distribution in the Jasper, Missouri metropolitan area, and Dalton expresses skepticism about the idea, and Pat almost instantly loses his fucking mind and attempts to slice Dalton open with a knife the size of a Little League baseball bat, and Dalton breaks his nose and tosses him through a plate glass window, and O’Connor assaults him and they both go tumbling through the place where the window used to be, and they fall first to a raised dais and then make their way to the main floor below after O’Connor bumrushes him over the railing, and Dalton pounds the crap out of him and eventually beats him unconscious, and doesn’t even bother to deliver a coup de grace, just kind of holds O’Connor up by his jacket for a moment and then drops him to the ground in disgust, and meanwhile Tinker, who during Dalton and O’Connor’s initial fight in Tilghman’s office punched Tilghman in the gut and then sliced Dalton open with his own knife and then punched Dalton in the face before Dalton kicked him in the chest for leverage to thrust himself and O’Connor through the window, meanwhile Tinker he suckerpunches Younger when he rushes through the door to see what’s going on, but then Hank comes in to help and he and Younger incapacitate Tinker and punch him in the gut while holding him still which is the kind of thing villains do but all’s fair in bouncing, and as Jack and Hank and Younger drag the punchdrunk bodies of their enemies through the bar and presumably to the exit, and Dalton is all covered in sweat and blood and getting ready to head out the back door and go seek medical attention, Tilghman, you remember him, Tilghman staggers over to the broken window and makes eye contact with Dalton and raises his right fist in a gesture of triumph and solidarity that’s one of the most ridiculously obsequious things Tilghman does in the whole movie, which in the parlance of our times puts it in the running for most ridiculously obsequious thing worldwide, I mean Tilghman contributed nothing to the fight, he just got winded by Tinker until he was rescued by the other bouncers, but there he is, small business owner, vicariously victorious in his non-worker role, and Dalton gazes into the fist of Frank Tilghman, as he raises that five-sided fistagon, as the bodies get dragged away.

065. “He killed a guy once. Ripped his throat right out.”

March 6, 2019When Frank Tilghman traveled to New York (City?) to hire the (second) best damn cooler in the business and also cast humorous aspersions on the size of his penis, we in the audience pretty much had to take his word for it. Dalton has great hair, a great body, a cool as ice demeanor, the ability to dupe Knife Nerds into leaving a bar of their own volition, and the stomach to stitch up his own knife wounds, yes. But actual bouncing? No evidence of that just yet, much less enough to decide that this lion-maned man is a one-man army in a throwdown.

Conveying just what Dalton is capable of in the clutch (literally) falls to Hank, the Double Deuce’s resident Dalton fanboy. When Dalton first arrives and word of his identity gets around—he tells Carrie Ann and Pat McGurn overhears and thus the legend is spread—the bar’s staff are all aflutter, some with excitement, some with skepticism, some with…whatever emotion covers “shit, I’m not going to be able to steal from the cash register/beat up patrons at random so easily anymore.” Hank is on the excitement end of the spectrum.

“He killed a guy once,” Hank tells his fellow bouncer Horny Steve as they lounge against a wooden post while wearing what would, if combined, amount to nearly one whole shirt. Hank shoots his left arm forward across their bodies, then pulls it back hard, raking his clawed fingers against the air just in front of Steve’s neck. “Ripped his throat right out,” he explains. He sounds like he’s talking about Regina George.

Our man Steven is unconvinced. “Bullshit,” he replies, only he pronounces it in that great movie-hardass way: “Bull shit,” two words, like the t-shirt the kid wears in The Jerk. And for all we know, Steve has the right of it. The way people have carried on about Dalton in this movie so far, there’s no telling what he’s actually capable of on the one hand, and how much his reputation has been exaggerated by the awestruck barfolk of the world. After all, Carrie Ann the extremely cool waitress recognizes his name instantly and reacts like she’s just realized she’s been making small talk with INXS’s Michael Hutchence. People are bowled over by this dude.

Also, and I think this is crucial to understanding a lot of what goes down in the first act of the film, nearly everyone we meet is very stupid. Dalton’s not and Tilghman’s not, that much is clear. But by the time the film hits the 15-minute mark, a grand total of nine words longer than two syllalbes, and zero words longer than three, have been uttered; of those nine, one is “peckerhead” and another is “attitudes.” It’s not difficult to imagine convincing Hank here that Dalton is bulletproof.

But even an extremely dumb clock tells the right time twice a day.

064. I Thought You’d Be Bigger Vol. 1: Tilghman

March 5, 2019At the end of their first encounter Frank Tilghman tells Dalton “I thought you’d be bigger.” This is Road House‘s primary recurring joke; you’ll hear it two more times from two other people. It’s probably swiped from everyone telling Snake Plissken “I thought you were dead” in Escape from New York, for what it’s worth. It’s a groaner, and it’s endearing in its groanerness over time.

It is also a weird thing to say to someone you just met. It’s a weird thing to say even if they’re a person whose job is usually associated with being of a certain size. Imagine meeting a professional wrestler or basketball player and saying that: You can picture the mechanical smile and hear the canned response already, right? Because chances are it’s not the first time the person in the job usually performed by a bigger person has been made aware that they are, comparatively speaking, smaller. It’s more likely that they’ve thought about this for literally decades, like since they were in first grade, than that this charming bit of banter will catch them delightfully unawares.

Frank Tilghman is a weird guy, though, whether by design or by Kevin Tighe’s inability to play him any other way. (A reader I’ve since argued with because I think it’s more likely Steven Spielberg has cinema’s best interests at heart than Netflix does suggested he auditioned for the Brad Wesley part, got Tilghman instead, and simply decided to play the role as Brad Wesley anyway, and it’s a damn good theory.) If you could dress a leer up in a bolo tie, that’s Frank Tilghman. He looks like a police sketch based solely on an eyewitness saying “He was some kind of pervert.” If you can watch him during the opening of this movie and not assume he’s the villain of the piece, I think that constitutes a Turing test failure.

Nevertheless he is one of the good guys, he has no ill intent toward Dalton, at no point does he do anything to antagonize or undermine or bamboozle or even overtax Dalton during his employment at the Double Deuce. This only makes “I thought you’d be bigger” even weirder.

Yet the way he says it is the weirdest thing of all, way more than the mere fact of saying it. He’s closes a deal bringing the best young cooler in the nation into the fold for a cool mid-six-figure salary, with no set start date. He does this while watching Dalton a) stitch himself up from a knife wound Tilghman also watched him incur minutes earlier, and b) summarily quit his current job while treating the owner of the bar he’d worked in like dogshit. And what does he do on his way out the door but pause, flash that unmarked-van grin, and say “You know, I thought you’d be…bigger.” The ellipsis represents a pause so pregnant with implication and innuendo its water is breaking, and the emphasis on bigger is definitely in the original, and did I mention he literally looks Dalton’s shirtless body up and down as he says this?

Now then. Do we have reason to believe Tilghman lusts after Dalton? Yes: Dalton is reason enough for anyone to lust after Dalton. Do we have reason beyond that? Yes: My theory that he and Pat McGurn were at one time involved romantically for one thing, or my other theory that the mysterious fortune he’s suddenly come into that allows him to renovate the Double Deuce and hire Dalton to keep the place secure came from an old rich widow he seduced as a closeted gigolo, persuaded to change her will to make him her sole beneficiary, and then tossed over the railing of a cruise ship, like the “Not great, Bob!” storyline from Mad Men, would (if true) indicate he is attracted to men and also makes destructive decisions in that regard. Are we intended to read his “I thought you’d be…bigger” as both a come-on and a sexualized dick joke? Yes: Our eyes and ears are not lying to us.

Do we need to respond with the kind of gross shitty gay-panic laffs we might have expected from movies and audiences alike for decades prior to this film’s release and at least a couple decades after it? No! The proper way to respond is this. First, to paraphrase RiffTrax’s Mike Nelson, the question of whether Kevin Tighe is trying to bed down Patrick Swayze, or the character equivalents of same, is a fascinating one on its face. It’s like when you learn Kate Beckinsale has a kid with Michael Sheen, which many people just learned when they also learned Kate Beckinsale is fucking Pete Davidson, the Saturday Night Live lotto winner who was previously fucking Ariana Grade. “A lot going on here,” I believe is your American expression, yes?

Second, and more importantly, this is a workplace safety issue, because Frank Tilghman absolutely is sexually harassing his new employee here before his first day on the job! Frank Tilghman may be on the side of the angels where the larger war for the soul of Jasper, Missouri is concerned, but he is without question an awful boss. Remember that before Dalton, Tilghman’s hires (that we know of) include two Brad Wesley goons and an extremely surly and obvious coke dealer and a guy who allows teenagers into the bar so he can have sex with them. The fish rots from the head.

Seen in this light, “I thought you’d be…bigger” becomes more than a come-on or a dick joke. It’s a cry for help. Frank Tilghman knows the magnitude of the task ahead of him—not cleaning up the Double Deuce, that’s just a metaphor, but cleaning up Augean stables of his very soul. To Tilghman, that is Dalton’s true task. Beneath the clumsy curiosity about his new hire’s penis lies the real question: Is he man enough to make me whole?

061. The Third Rule, Verse 2

March 2, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, again, is the third.

3. Be nice. (continued)

When first we assayed the Third Rule, I said the following:

It is the shortest rule, and it requires the most explanation. It is the least practically minded rule, and it is illustrated with the most practical applications. It is a rule about being kind to others, on the surface at least, and it is the rule greeted—and at times delivered—with the most open incredulity, even hostility.

When Dalton tells the assembled staff of the Double Deuce to be nice, it is Jack the bouncer who, whether in spite or because of being Dalton’s best student, opens the door for doubt. “Come on,” he says, gently but with unmistakable disbelief. He’s trying to ask his new sensei “Are you out of your mind?” in the politest possible way.

Now comes the yin-yang instructional configuration that should be familiar to us as central to the Giving of the Rules. Dalton leans forward and tells Jack “If somebody gets in your face and calls you a cocksucker, I want you to be nice.” Jack responds with a skeptical “Ohkayy”—and, though he knows it not, passes the test Dalton has just given him in so doing. Dalton got in his face and called him a cocksucker, and he was nice. It takes the doing of the thing to see that it can be done and learn how to do it. If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.

(to be continued)

059. Men in Black

February 28, 2019When I wrote about Wade Garrett yesterday, I remembered something about his black t-shirt: He’s not the only cooler in the movie to wear one. The other of course is Dalton—but it’s not like he wears it all the time. The movie shows us he’s molded in Wade’s by deploying black in his wardrobe on three key occasions.

Attentive readers of Pain Don’t Hurt will have guessed the first by now: The Giving of the Rules. This takes place prior to Wade’s introduction, directly linking the older man’s debut to the establishment of his acolyte’s doctrine.

The second is the fight that takes place the night he and Doc have their first date, which is also the first time we see him on the job after we meet Wade. This reinforces the sense of succession while also tying Dalton’s romantic flourishing to the older man’s tutelage.

The third is his impromptu breakfast summit with Brad Wesley, during which Wesley brings up his checkered past and offers to hire him away from the Double Deuce. It’s not a t-shirt here but a collared shirt, as befits this more formal occasion. But the dialogue makes direct reference to an event in Dalton’s past that Wade will also bring up (while wearing a collared black shirt himself) later in the movie, and shows Dalton standing up to an asshole in a way that would do his mentor proud—even if he’d likely suggest getting out of Dodge afterwards.

Clothes make the man. Clothes mate the men.

057. “It’s my way or the highway.”

February 26, 2019Dalton, during the prologue of The Giving of the Rules: “It’s my way or the highway.”

The highway:

Show me the lie.

Whether by accident or design—who can say? alright I can say, it’s by accident—there is no aphorism, no catchphrase, no idiomatic expression, no imbecilic threat or come-on or dick joke in the entirety of this film that does not bear close, even literal, reading. This is what I want to impress upon you more than anything else. This is what inspired this project: the sense that in the 15 years I’ve been watching this movie I haven’t touched bottom any more than you might during a swim in the middle of the ocean. Road House is a journey of discovery, a highway if you will, and the higher you fly the deeper you go the deeper you go the higher you fly so come on come on come on it’s such a joy.

056. Gi

February 25, 2019Several martial-arts disciplines utilize the gi, a simple uniform developed over time with the physical and strategic demands of each particular discipline (judo, karate, whatever) in mind. Dalton, who in another life would have made a hell of a mixed martial arts fighter, likes to wear his out on the town sometimes. It’s the only outfit we see him in not once but twice: first on the day he takes a trip to the auto parts store and discovers that Red Webster is getting shaken down by Brad Wesley and his goons, and second on the day of his final mad battle against the Wesleyans. Dalton is wearing a gi when Red springs the original colloquialism “Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick?” on him in lieu of the traditional “Is the Pope Catholic?”, and again when he approaches his niece Dr. Elizabeth Clay in the middle of examining the x-ray results for her latest trauma patient and/or colonoscopy recipient to beg her to skip town with him so they can avoid the wrath of her insane Fotomat-owning ex-husband. But I assure you that in neither case did he slip this clean white garment on in anticipation of seeing action. It’s simply the film’s way of communicating that the Dalton Path stretches from East to West. In many ways it’s an equivalent signifier to stretching with a lit cigarette in his mouth, or waking up hung over from a late-night binge-read, or receiving a philosophy degree from NYU for studying “man’s search for faith, that sorta shit” prior to becoming a professional ass-kicker, or asking for a king’s ransom as a salary but living in a place that costs $100 a month and driving a car chosen specifically because it’ll function basically the same if it gets half-destroyed by angry drunks whose noses he’s broken, or doing tai chi by the water in between tours of every greasy spoon and dive bar in town. He is a human mixed martial art. Might as well dress the part.