Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: An interview with Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez

October 4, 2010NOTE: Back when I worked for Wizard magazine’s website, WizardUniverse.com, I conducted a series of interviews with alternative-comics creators titled I CAN HAS COMIX? That title was a little problematic with some folks at the company — as were the transcription bills — but whaddayagonnado. I kicked the feature off on June 22, 2007 by speaking with Los Bros Hernandez, and I’m reposting the interview here because I think it’s a pretty solid introduction to/overview of the brothers, Love and Rockets, and what I get out of it all.

I CAN HAS COMIX?: GILBERT AND JAIME HERNANDEZ

In Wizard Universe’s new alternative comics interview column, Los Bros Hernandez reveal how their shared love of punk rock, sexy girls and Silver Age classics helped their epic series Love and Rockets launch the indie scene as we know it

By Sean T. Collins

I’ll admit that it took me a while to hitch a ride aboard Love and Rockets.

Despite the near-universal acclaim the series and its creators have received over the 25 years since the series’ first issue took the comics world by storm and kick-started a small-press revolution–the fruits of which can be seen at this weekend’s MoCCA Art Festival in New York City–there’s something daunting about it. For starters, it’s not just a straightforward one-man show: It’s an umbrella title for the work of Los Angeles-born brothers named Gilbert and Jaime (and sometimes even older sibling Mario), collectively known as “Los Bros Hernandez.”

What’s more, both Gilbert and Jaime have developed their own mini-mythoi within L&R, featuring enough characters to rival your average superhero universe. In Gilbert’s case, you have the busty, hammer-wielding femme fatale Luba and her friends, lovers, family and enemies, all swirling around the fictional Latin-American town that gives Gilbert’s “Palomar” saga its name. Jaime’s stories center on unlucky-in-love mechanic Maggie and her obnoxious punk-rock best friend/sidekick/sometimes-lover Hopey, wild women who are the stand-out members of a loose-knit group of L.A. ladies dubbed “Locas.” Both casts of characters age in real time, meaning some people who started the series as teenagers now have teenagers of their own, with their own adventures. The warts-and-all presentation of the series’ leads (particularly Jaime’s, in my case) can leave you as pissed of as you’d be at your own obnoxious friends.

And to top it all off, Love and Rockets has spawned two separate ongoing series using that title, a raft of trade paperback collections, two massive hardcovers housing nearly the entire “Locas” and “Palomar” sagas, and countless spinoff miniseries, graphic novels and even adult comix. Put it all together and it’s enough to make the friggin’ Legion of Super-Heroes’ continuity seem easy to follow.

Until now.

To celebrate L&R‘s 25th anniversary, publisher Fantagraphics recently began releasing awesomely affordable, handily portable softcover digest collections, starting at the beginning of both brothers’ epic storylines and giving readers their best chance ever to get in on the ground floor. With the first volumes (Jaime’s Maggie the Mechanic and Gilbert’s Heartbreak Soup) already in stores, the second installments–The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S. by Jaime and Human Diastrophism by Gilbert–launched this week, with some of Los Bros’ best work ever on board.

I could go on about both brothers’ mastery of character development, creating people as flawed, funny, and fascinating as your best friends. I could wax rhapsodic about their sophisticated storytelling, which relies on the readers’ intelligence as it bounces back in forth in time and between dozens of characters. I could point out that at different times, it’s the funniest, raunchiest and scariest comic you’ll ever read. I could talk for ages about the gorgeous art–Jaime’s sharp, sexy, stylish classicism and Gilbert’s earthy, equally sexy surrealism. And I could say that while you hear a lot about “creating a universe” in comics, no one’s ever done it better than Los Bros–when you read an L&R story, you feel like you’re catching just a small glimpse of a world as big, sprawling, messy, funny, horny, heartbreaking and real as our own.

Instead, in this joint interview with Gilbert and Jaime, I’ll let Los Bros themselves explain the inspiration of the series, reveal the dark secrets of the stories in the new digests, and announce their pick for the greatest superhero comic of all time. Through it all, it’s clear that when it comes to creating thrilling uncategorizable comics in Love and Rockets, the brothers are still armed and dangerous.

WIZARD: Take us back to 1981 when you guys started the books. What made you say, “Let’s do this”?

JAIME: Let’s see, 1981…I was being paid to go to junior college, so I didn’t want a job. I was just taking art classes and stuff like that. I wasn’t thinking about what I was going to do with my life–I just liked drawing comics. By that time we were drawing comics for ourselves, but we were starting to draw them with ink on the right paper and everything, not just on a piece of typing paper with a pencil. We wanted to print it somewhere but we didn’t know where, because it wasn’t your normal Marvel or DC fare. There wasn’t really much of a market for this stuff, we thought. We were still punk rockers in bands and we were just doing comics. We wanted to draw comics the way we wanted to see them, and we weren’t really seeing much of them out there.

GILBERT: Comics were our amusement for years, and what we were into was not what the mainstream companies were into at the time. We figured that by printing an underground magazine we would get it out there, mostly to see what the response would be–just something to do, really. It turned out that when we finally got our stuff together and put out a 32-page Love and Rockets comic, a fanzine/underground type thing, we were luckily noticed right away by Fantagraphics. The timing was just right–they were ready to publish their own comics. It took a little climb to get Love and Rockets going, but the response was very good, even in a small way at first, so that encouraged us to continue.

It’s not too often that people in the alternative comics area have that kind of success right out of the gate, but I guess you guys didn’t have a lot to compare it to. Before Love and Rockets there were the undergrounds, but they were sort of a different beast.

GILBERT: Yeah. Cerebus and ElfQuest were actually encouraging in the sense that it could be done, getting a following for a black-and-white comic. It wasn’t necessarily mainstream. Even though they were both geared for that audience, they were successful on their own.

Jaime, you had more “mainstream” elements in your early work, with its sci-fi flavor. Was that an attempt to tap the normal comics-reading audience, or was it just you following your bliss?

JAIME: It was pretty much just me. I liked drawing rockets and robots, as well as girls. [Laughs] It really was no big game plan. It was almost like, “Okay, I’ll give you rockets and robots, but I’ll show you how it’s done. I’m gonna do it, and this is how it’s supposed to be done!” I went in with that kind of attitude.

That’s definitely a punk attitude.

JAIME: Yeah. I’d see something was being done in other comics and I’d say, “Ah, no, no, that is not the way to do it. This is the way to do it.” That gave me encouragement to just do it. In the beginning, I was putting my whole life of drawing comics since I was a kid into this comic. When the characters started to take over, the other stuff started to drop out because it was getting in the way.

And the result was a book that’s been credited with inventing alternative comics as we know them, though that couldn’t have been your intention at the time.

GILBERT: I think that we did create a path, at least, using all our influences and what we saw about comics that we knew of since we were kids. That developed into mainstream comics in the ’60s, and undergrounds in the late ’60s, and then in the ’70s you’d have mainstream companies that would also publish black-and-white magazines–different things bouncing around here and there with a different format. That was encouraging to us as well. I think what happened with Love and Rockets is that since there really weren’t the kind of comics we were doing, that is bringing our mainstream influences into a new kind of comic, a new kind of underground, let’s say. An underground with more going on, hopefully. [Laughs] At least I would like to think so. It basically created a path for everybody to at least get on, not necessarily making it easier, but just [having] something there. It was just a different road to go down, and I think that is what we did somehow.

In each of your main storylines, you’ve both created these big, sprawling, interconnected casts over the years. Is that something that two of you talked over, or did it evolve spontaneously and separately out of what you both were interested in doing?

JAIME: I would say that it just kind of happened as the characters started to write themselves. I think because Gilbert started creating all-out characters, it just seemed like a good idea to me, or something. On my end, I basically just created characters that would fill in the gaps of the story. If I needed someone to say something in the back that was totally unrelated to the characters, I would create a character later on. What started out as a drawing of just somebody, I decided, “Hey, I’ll make that someone’s boyfriend.” While in the beginning they were just there to color up the place, after a while they started to take on lives of their own. That is how the characters started to multiply. What about you, Beto?

GILBERT: It would probably be my mainstream influence, with me. Like in, say, Peanuts: You could follow the strip with Charlie Brown and Linus for a few days, and then it would shift to Lucy and Violet. But you wouldn’t lose what the strip was about; it was because all the characters were so well informed that you are always in the Peanuts world. Even if sometimes it was about Snoopy or Sally Brown or whatever, you were always there. That’s on the high end, but in the middle there would be the Marvel Universe, actually, for me. I always liked what fans complain about now: the fact that they were all interconnected. If you needed something heavy and metallic and electronic, you went to Stark Industries. If you needed power, you went to Reed Richards’ unstable molecules. I always liked the crisscrossing of that. Of course it went into madness eventually [laughs], but at first it was very intriguing to a kid. It was something new for superheroes, that interconnecting. In the Hulk comic you could mention Stark Industries, and Iron Man or Tony Stark was nowhere near it but you knew what they were talking about. That is what I liked about it: that interconnecting, even when stuff is off camera. That is pretty much what inspired me to go ahead and do that with mine. That way, you just have a larger canvas to work from.

That’s a big part of L&R‘s appeal–you get the sense that we are following this handful of characters right now as they do things during the course of their day, but that if we just took that camera and moved over a couple of blocks, you could catch someone else in the middle of what is going on in their lives, too.

GILBERT: Yeah, and another aspect is that is how our family worked as well. That’s something we brought from home. Our family, our cousins, aunts and uncles were all interconnected the same way. That was an influence as well, the family unit.

JAIME: Yeah, it was a big family. Our aunt had six kids and our other aunt had six kids.

Talk a little bit about your main characters. In your case, Jaime, it’s Maggie and Hopey, the stars of The Girl From H.O.P.P.E.R.S., and with Gilbert it’s Luba, the main attraction in Human Diastrophism.

JAIME: Maggie started back in high school, where I wanted to create a character I could put into any type of story I wanted–send her to outer space, back to time, to her grandma’s house. She was just a drawing at first, and I just started to think wherever I go, Maggie goes. It took a while, but I put a lot of my thoughts into her, and that’s why she’s the main character and the stories follow her. I created her friend Hopey out of just wanting a sidekick, and seeing the punk girls in L.A. at the time; that was when I was first going to the punk shows. They just kind of hit off together. My Betty and Veronica, you could look at it that way. Or my Batman and Robin. [Laughs] They just worked. When we did the first issue, that was the first response I got: “I like your girl characters.” I went, “Cool, because I like doing them!” [Laughs] That is basically how that started, and Maggie continues because I know her so well and I can put a lot of stuff into her.

GILBERT: My work around the beginning was similar to Jaime’s: a science fiction, two-girls-hanging-out-type thing. Once Jaime’s came out, the response to it was immediate. I could see how much more defined it was [than mine] and how much potential it had. Jaime had already grabbed it and was working that side of it just fine, so I abandoned my stuff and thought, “What is it I really want to say that’s different?” I just kept going back to the idea of this imaginary Latin-American village [called Palomar]. The more I thought about it and the more I felt it out, the more it seemed right. It was completely different from what Jaime was doing. Even from the beginning I thought that Love and Rockets should be a bigger thing. It shouldn’t be just all the same thing, and since Jaime was taking care of that part of it, then doing something completely different but still on the same page would make Love and Rockets a bigger thing, a bigger work of art. So that’s where the encouragement came from, bouncing off the fact that Jaime’s was done and already the response was good, so all I had to do was fill in the rest. I was a little freer, actually, to do something that might not have been commercially viable. I think that Palomar was a little chancier than doing the girl/rocket stuff at the time.

JAIME: I could tell you that Gilbert’s approach helped me a lot in taking the girls out of the science fiction, to handle stuff more at home. Gilbert was the older brother, anyway, so he really did everything before me, ever since we were little. [Laughs]

GILBERT: What’s very interesting about the science fiction stuff is that the question we get asked the most, at least out loud, is “Where is the rocket? That’s the real Love and Rockets.” Oddly, that’s the smaller segment of the audience–they’re just more vocal. The real audience is the one who followed Maggie and Hopey’s adventures as real girls, so to speak, and the Palomar stories. That is the real Love and Rockets reader. But for some reason we have the most outspoken ones saying, “When are you going to do the rockets? It’s called Love and Rockets!” That’s fine, we love doing rocket stuff, but the real Love and Rockets is what we are famous for.

You mentioned that the audience has changed, and now the less genre-y things are actually more commercially viable. Jaime’s had his work published in The New York Times, your recent collections have gotten major mainstream-publication review acreage–could you ever have seen this coming?

JAIME: I think that for me, it was more a case of, “One of these days, sure, I’d like my character standing next to Charlie Brown and Betty and Veronica and Superman.” But I was just hoping we would be able to continue doing it and hopefully make a major living off of it because I didn’t want to do anything else with my life. It was like, “Oh boy, I can continue!” But “How long is this going to go?” I wasn’t even thinking about it. Twenty-five years later, I’m going, “Wow, a quarter of a century and I’m still allowed to do this?” It’s amazing. I just think back to all the talented people I knew in the past who had to stop because they just couldn’t live off of doing their comics.

GILBERT: The one time I got thrown was when we were getting a lot more attention doing Love and Rockets and people were really accepting what we wanted to do in it. What really threw me was when I got to a point where readers would tell us, “I used to read Batman, but now I read your stuff.” I thought that was really creepy. I’d go, “You mean you’d rather read us than Batman?” Batman, Superman, all that stuff–they were icons when we were growing up. Nobody ever thought somebody would rather read stuff that wasn’t that. It just threw me and was something I never really thought about, that someone might like a different kind of comic outside of the Big Two. For us it was always a note of encouragement: “We just better step up to the plate then. If this is what they are saying about us, if this is what they like about us, then we better be good!” And we’ve done our best to stick to our guns about giving the most honest comic we can–coming from our point of view, of course. But it threw me for a bit. It seemed like we were being scrutinized for a while, like, “Okay, this stuff is getting more attention than The Incredible Hulk, so let’s see what they’re gonna do next.” We were like, “Oops!” The only thing you can do is try to get better. Otherwise you’d crumble if you tried to compromise or change things.

What do you think of the new digest versions of your work?

GILBERT: For me, I just trust our publisher. I don’t have the say of how it is going to be packaged, because I couldn’t tell you how, so I have to trust them a lot. I think it’s great if it’ll just give us shelf space. Don’t colorize it or something like that. [Laughs] But as long as it’s presentable and someone will put it on their shelf, that’s all I can ask for.

Jaime, your latest digest includes “The Death of Speedy” and “Flies on the Ceiling,” two of your best-known–and darkest–stories. How did each of them come about?

JAIME: Back before “The Death of Speedy” and “Flies on the Ceiling,” I did this story about Speedy talking to his friend about his sister Izzy. He mentioned how she was all normal and then she went to Mexico and came back weird. When I wrote that, I didn’t know exactly what happened to her. I got that question every time: “What happened to Izzy in Mexico?” I’d say, “Oh, I’ll tell you one of these days.” But to myself I was saying, “Yeah, when I find out!” [Laughs] It took almost 10 years to write. It all came from that, and it took on many forms and shapes and sizes till I finally did “Flies on the Ceiling.” With “The Death of Speedy,” certain continuity was building up in the drama, and all of this was building up to where I wanted to kill somebody. I wanted someone to die. But it was another one of those things where I thought, “I’ll show you how to have someone die.” I was going to challenge myself and everybody else. Speedy became the guy just because of the way things were going: I wanted to kill a main character, and he was a victim of my plans. [Laughs] It didn’t have to be him, but it ended up being him. Years after that I asked myself, “Should I have ever killed him?” It was just one of those things that he fell victim to.

Do you ever wish you could bring him back to life, Superman-style?

JAIME: That’s the cool thing with Love and Rockets: You can always have flashbacks. It doesn’t mean they come back to life; you just tell a story that happened not to screw with history. Which I get really close to, sometimes, just because it’s tempting. I can always bring Speedy back–just in the past. I don’t want it to become formula. I have to do it right.

Gilbert, in your case, again, it’s fairly dark material, since “Human Diastrophism” is about a serial killer preying upon Palomar. What made you let loose this violence on these characters in this town you created?

GILBERT: There was no direct line, no conscious effort to be that dark. It just sort of came out as the stories were developing. Whatever darkness there was is from my unconscious. I don’t really know what the source, but I just wanted darker stories. I was also tired of the cramped format, doing a few pages an issue; I wanted to do a longer story, and the longer the story is, I feel I have to give more. I was basically doing stories unchecked, throwing everything in that I could. In those days I would write stories thinking, “When I finish this story, if I get hit by a truck the next day, then I’ll be satisfied that this is my last story.” I don’t do that anymore. Now I think, “Oh, that was my first story,” and that works just as well when I work. “This is my first story, I’m just getting started, I’m just learning.” In the old days it was the other way around: “Okay, if I’m done with the story then I’m done, but I better get down to business.” I wanted to do the world in a microcosm that had death and rebirth. Everything that you can imagine in an epic story, I tried to stick it in one big story. Like Jaime’s story, I chose a character because whenever you are dealing with a story that big and that universal, the characters that you hurt the most have to be ones you care about, unfortunately. You can’t just make up a character and kill them, because it doesn’t matter. If it’s a character that the readers cared for to a degree, that’s what gives the story more resonance, especially in a large story like that. We don’t really do it to shock or anything, but it’s just part of life.

That is what I was going for with that. And once I was done with it and it did get very good response, then what do you do after that? You just start all over and do your damnedest not to cheapen the story. You try not to refer too much to that story, unless it’s little things you need that you left out or something. Jaime and I are clever enough to bring back those characters in a legitimate way, without cheapening it. In Jaime’s “The Death of Speedy,” you never really see what happened–it could have been somebody else and not Speedy who was killed. There’s that little twist that you can do and make it convincing. The same with Tonantzin setting herself on fire in my story. I could very well say it wasn’t her, it was a set-up. I’m just saying that we’re able to do stories where we can make it work–we’re just not going to. It’s too easy, it’s too pat, and it just cheapens the earlier story.

The characters in both the “Locas” and “Palomar” stories aren’t like the ones in Peanuts or in Riverdale High or in the Marvel Universe–they age in real time. Why’d you make that choice, and do you ever regret it?

JAIME: First of all, it was Gilbert’s idea to actually age them. I’ll let him explain.

GILBERT: I was thinking of a sprawling epic that took years to complete. I think I aged them too quickly for my taste now. I definitely regret that it was a little too quick compared to how long we have been doing it. We’ve been doing it for 25 years and that is not really too quick, but it is in terms of comics because I’m still doing them. I’m not done with the characters that are getting older. What happens is you get the “Tiny Yokum syndrome”: The old strip Li’l Abner was about a bachelor who was being chased by a lovely woman, [and eventually] they married and had a kid. Well, now Li’l Abner is responsible. He can no longer have wacky, nutty adventures because he’s married and has a kid. He has to stay home and take care of the family. What they did was create a character, his little brother, named Tiny. Basically, Tiny had the adventures that Li’l Abner could no longer have–but we don’t know Tiny, we know Li’l Abner. The problem that happened with aging my characters too quickly is that I had to come up with characters to replace the older characters, and it’s not as good. I’ve had several characters to replace my main character Luba, but none of them are Luba. That presents itself in that way, even though some readers probably don’t even know who Luba is because they only read the new ones. That’s fine, but it’s something I regret a little bit, and I keep pushing the main characters back.

Jaime, earlier you compared Maggie and Hopey to Betty and Veronica, but in this case there’s no Archie. Both of you focus on female characters. Was that a conscious choice? Did you just like drawing girls or did you really think you had something to say about women?

JAIME: I think it all started when I was a budding teenager and Gilbert was a teenager, and he said, “Jaime, you should start drawing girls.” And I went, “No, I can’t do that–Mom will kill me!” And he just goes, ‘No, it’s cool,” because he was drawing girls left and right. I started and I thought, “Oh God, I can’t draw girls–[mine] are so terrible!” Then after a while you couldn’t stop me. It all started from wanting and liking to draw women. They are much more fun than drawing men. I thought, you can have your cake and eat it too if you do your comic starring the women instead of the men. You can have men, but you get a lot more done if you are drawing a character you like. At the same time, it’s something Gilbert talked about earlier: When I was young, I always felt that if I was going to put something in my comics, I had to back it up. I had to step to the plate and be responsible. So there was always talk about T&A–“You just like women as objects” and stuff. I was like, “No I don’t–look!” So I started making them characters. I thought, “That’s easy! Just do it! I don’t have to feel responsible to create 10-hundred male superheroes to 10 female superheroes–I can just concentrate on the female superheroes!” That’s how it started for me. Gilbert was well on his way before me, being the older guy. I just followed along.

GILBERT: A lot of Love and Rockets is just simply what we wanted to do, even superficially–if we feel like drawing a person wearing these clothes, doing this thing, just because we feel like drawing that. Most of the time it’s a woman doing it. Then we started giving the characters personalities, like Jaime said, having our cake and eating it too. There was a weird little rub there because we kept getting asked, “Why are you doing women?” Just the fact we were asked that all the time, it was like, “Something is wrong here if you have to ask us why. Why do anything? Do people ask Frank Miller why his stories are so violent?” People are fine with violence but they’re nervous about women for some reason. So we are always up to the challenge. We stick our elbows up and go, “Look, we’re gonna do this and we’re gonna do it as best we can.” We kept getting encouraged–the more we did it, the more good response we got. Then every once in a while, “Why do you do women?” and I thought, “It is really a boys’ club out there, isn’t it?”

JAIME: It was almost like the more they told us not to, the more we did it. It was like, “I don’t see anything I’m doing wrong here. What am I afraid of?”

Who do you consider your peers? What other comics out there interest you?

JAIME: It’s harder for me to say now, because I’ve gotten so locked in this Love and Rockets world of mine, creating my stories and not looking at anyone around me, so I don’t know. I guess it’s competition on the shelves: “Who’s taking up my shelf space?” That’s how it is [now]. When Gilbert and I started out, it was like we were welcomed by the mainstream when the comic first came out, but we didn’t have the heart to tell most of the mainstream, “We don’t want to do what you guys are doing.” I didn’t want to be an assh— about it or anything–we were getting all this support–but we thought, “Oh, so you’re gonna do Secret Wars? After we talked about how there’s a new comics world, you’re gonna go back and do that? Well, fine, you do that, but don’t ask me why I’m not.” It wasn’t till more alternatives and people with their own goofy comics like ours started popping out that we started to get these peers coming out of the woodwork. I would say when the Peter Bagges and the Dan Clowes started coming out too, we kind of formed this little… I don’t want to say club, because everyone lived in a different state. [Laughs] But we liked seeing each other at conventions and events like that.

GILBERT: Were you talking about peers now?

That would be the follow-up. Are you also “head-down,” like Jaime?

GILBERT: I am, pretty much. I’m just so focused on getting work out that I look for influences and for other things to inspire me, [and] rarely is that another comic book these days. One reason is that alternative comics, as far as series go, are barely there anymore. Love and Rockets is one of the few that comes out on a relatively regular basis that continues this old tradition that is pretty much gone now. It’s mostly graphic novels and online comics. It’s just different, and a different way to get ahold of comics. The alternative comics they call pamphlets now are simply not around like they were. I don’t look at comics on the Internet. I don’t really look at the Internet too much. I’m focused on writing the best comics I can, and that takes up most of our lives, really. I don’t want to dis anybody or ignore anyone–I’m just not really focused on things outside at this time.

JAIME: I find that when I go to a comic store I leave with an old Marvel or DC archive 99 percent of the time.

It is kind of a golden age for that stuff. The sheer volume of old stuff that is coming into print in really nice books is amazing.

JAIME: Gilbert told me recently that they did the complete [Steve] Ditko Amazing Spider-Man, and I’m just achin’ to go and get that.

GILBERT: Actually, that just came out, and here is a plug for Marvel. I think that now that that’s collected, the Ditko-[Stan] Lee Spider-Man, I think we finally have a book to show and put down and say, “This, for me, is the best superhero comic ever right here.” There has been stuff that has been pretty close, like [Will Eisner’s] The Spirit and [C.C. Beck’s] Captain Marvel and other things, but this, to me, is the grail of superheroes. It’s great to have it in a package like that. Which means I have to rebuy it. [Laughs] I’ve bought that stuff so many times now in different formats.

JAIME: So this is what we’re influenced by, see? [Laughs] We have nothing to show about the new stuff–this is all stuff we liked when we were kids.

What does Love and Rockets have that would appeal to the kinds of readers who haven’t said yet, “I used to read Batman, but now I read you guys?”

JAIME: It’s more difficult these days, because there are more ways of getting ahold of comics with the Internet and different things now. I think what hooked people, the mainstream readers, from reading Batman or Superman and went to Love and Rockets is that [we] were serialized at the time. New stories about Maggie and Hopey were continued from issue to issue, new stories about Palomar continued from issue to issue. The reader could identify with that, reading a serialized adventure that was similar, superficially, to reading a Batman comic. Now Love and Rockets is different, a little more fragmented, a little more experimental, a little more idiosyncratic, I think. It’s different from how mainstream comics are read now. I get a bunch of free [mainstream] comics every month, and I look at them, and you got to be really into them to know what’s going on. You have to be a fan of that particular book to know what is going on. It’s a different day now, a different way to look at comics now, so it’s probably not as easy to grab that audience these days.

I know when I started getting into you guys it was difficult because of the array of formats and editions that were out there: You had the ongoing series, the trades, the spinoffs…But I feel like now, with the digests, it’s nice and easy. In the same way that now a lot of the superhero comic book companies are collecting the complete Lee-Ditko Spider-Man and all these big giant historical runs of series in these easy-to-follow collections, it’s now a better time than ever to get in on the ground floor of Love and Rockets and start from the beginning pretty easily and affordably. I’ve seen it happen around the office–those digests spread like wildfire.

JAIME: I imagine that is what is going to happen with reprinting this old stuff. It’s sort of like seeing 11-year-old kids with Ramones shirts now–three of the main Ramones are dead. [Laughs] Their music is over 30 years old now, and 11-year-olds are into the Ramones! So you never know. There could be a Lee-Ditko Spider-Man comeback with kids. Who knows?

GILBERT: I met an 8-year-old kid a couple of years ago whose mom kept badgering him: “This guy draws comics! Tell him who your favorite Spider-Man artist is!” And the kid, under his breath, goes, “Ditko.” I was like, yes! [Laughs]

JAIME: Ditko quit in ’67, so it was a long time ago. It’s kind of cool, things being in perpetual print.

Any closing words of wisdom?

GILBERT [in mock-pretentious voice]: We’re not only mainstream geeks here– we’re actually progressive artists. [Laughs] I’m kidding. I don’t know about the progressive part and I don’t know about the artist part. [Laughs] We’re going to continue doing Love and Rockets projects that strike our fancy. And I have a couple of other books coming out. One will be a Dark Horse miniseries which will eventually become a graphic novel called Speak of the Devil–that’s in stores this July. I have another graphic novel coming out in June called Chance in Hell, and that’s my first actual graphic novel with Fantagraphics. It’s in the digest size–not quite as small as manga, but around that size. Hopefully, the casual reader will be like, “Hey, there’s a small book–it must be manga!” [Laughs] That could help!

Comics Time: Locas, or Announcing LOVE AND ROCKTOBER

October 1, 2010NOTE: Nearly six years ago, I panned Jaime Hernandez’s life’s work in The Comics Journal. Though this is probably the Comics Journal-est thing I’ve ever done, for the Journal or anywhere else, it’s not one of my prouder moments as a critic. At the time I was coming down from the high of brother Gilbert’s epic Palomar hardcover and his two stand-alone masterpieces Poison River and Love and Rockets X. By comparison, Jaime’s stuff, though prettier on the outside, was basically about the female Latina punk versions of Beavis and Butt-Head. Unable to see past the fact that Maggie and Hopey were annoying and did stupid shit a lot of the time, I gave Locas, which collected all their stories from Love and Rockets v1, a bad review.

Here’s where I make up for it.

I happy to announce the start of LOVE AND ROCKTOBER here at Attentiondeficitdisorderly. For the next month, I’ll be devoting my regularly scheduled Comics Time reviews to as much of Los Bros Hernandez’ work as I can get through, starting with the Jaime material I misguidedly maligned. I believe that Love and Rockets is all but unique in comics in the way it has taken advantage of serialization to slowly create a rich and enveloping world peopled with multifaceted characters who seem to be living lives on and off the page. And it did this twice, simultaneously! With this in mind I think it’s a book that’s best consumed the way great TV shows are best consumed: In huge, weeks-long binges. It may be Fantagraphics’ wonderful Love and Rockets digests facilitating this rather than Netflix, but the principle is the same.

So, first up, Jaime and the Locas stories. After that? I might continue forward with Xaime till I’m caught up. I might switch over to Beto’s stuff. (And Mario’s too!) I might do both (which I imagine would necessitate LOVEMBER AND ROCKETS). I might do neither. But whatever I do, I’m going to enjoy the hell out of it, and I hope you do too.

First, let’s start by revisiting sins past: My Comics Journal review of Locas, which I’d avoided re-posting here on the blog for years, waiting for precisely this sort of opportunity to serve as a corrective. Please take everything you are about to read with a grain of salt, as much of what I once saw to be weaknesses I now recognize as strengths. And Jaime, if you’re out there: Sorry, man!

—

Locas

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics Books, October 2004

712 pages, hardcover

$49.95

The first collection to span one of Los Bros Hernandez’ major output during the first 20-year run of their umbrella title Love and Rockets was Palomar, an anthology of brother Gilbert’s chronicles of the titular Mexican town. Aside from a few frustrating attempts to muddle through the multi-genre mishmash of Music for Mechanics, L&R‘s first softcover volume, Palomar was my first real exposure to Los Bros’ series. To say “it’s a tough act to follow” would be to imply that one of maybe the three or four greatest achievements in comics history could be followed at all, so instead I’ll say that I was almost totally unprepared for how thoroughly the book would floor me. Gilbert’s uncanny grasp of the totality of each of his characters allowed him to jump back and forth in time with ease, showing us different periods in their lives that for all their temporal disconnect never made anything but perfect sense for each indelible creation. His senses of humor, horror, and eroticism would each be enough to sustain the career of a lesser cartoonist for years at a stretch. The book succeeded as maybe the great long-form narrative in comics, even (as I learned later) despite the fact that it for some reason omitted major related works like Love and Rockets X and especially Poison River, without which much of the book’s concluding section was difficult to follow. Perhaps most impressively, Gilbert’s mastery of the formal stuff of cartooning — of line, design, characterization, caricature, panel transitions, the whole shmear — was so complete that I had to wonder (partially in skepticism, partially in giddy anticipation of fresh discoveries), “The other brother’s supposed to be the better artist?”

Locas, Love and Rockets‘ second definitive hardcover collection, focuses on the work of that other brother, the “better artist,” Jaime — and I’m not sure if I can remember a more awkward comics-reading experience than my recent sojourn through its 700-plus pages. I say this not because of the book’s unwieldy length. I say it rather because of the dual irony that this massive collection could consist of material that feels so slight, and that after reading the single longest comic book I’ve ever come across I should find myself with so little to say.

One thing I will say, since it’s unavoidable, is that the book is nowhere near the masterpiece that Palomar is. It could be argued that it’s unfair to compare the two works simply because their authors are brothers. Now, I don’t think it could be argued persuasively — when one spends years and years sharing funnybook real estate with one’s sibling and indeed adopts a collective moniker, one invites such comparisons — but that’s not even the point. Locas suffers in comparison to Palomar, but so do most comics. The point is that it suffers from much more than that as well.

Things get off to a rough start with the uneasy blend of sci-fi, soap opera and cheeky revolutionary politics found in “Mechanix” and “Las Mujeres Perdidas,” the two big storylines that begin the collection. This is not to say that even these unrepresentative, shaky stories do not have much to recommend them. Here Jaime’s art most clearly displays his classic influences, imbuing the dinosaur-fighting and rocket-flying action with beauty and dynamism. “Mechanix”‘ unusual structure — a series of letters from traveling mechanic Maggie to her best friend and fellow punk Hopey, punctuated with predominantly stand-alone panels which illustrate the text — serves as an early indication of Jaime’s great strength, that of graphic design. The title panels/pages Jaime constructs are inevitably the best looking part of any of his stories, as they allow his gifted use of high contrast and his inventive and iconic lettering and portraiture to shine; since “Mechanix” is essentially a series of such images, it’s awfully nice to look at.

Yet already the flippant tone Jaime adopts for writing his characters, one he will be unable to shake off throughout the book, works to his detriment. Maggie essentially has two settings for looking at the world: Everything’s either a goof or a tragedy. This gives these early stories, in which the lives of thousands of people, including our heroine and her friends, are often at stake in power struggles between crazed plutocrats, an air of frantic, bipolar absurdity that does not at all suit them. Perhaps the intention was a sort of Duck Soup-style lampooning of love and life in the nuclear age, but the stories come off as inconsistent and unsure of what they want to be and how they want to be it.

Before long the sci-fi trappings are shed entirely, seemingly more out of embarrassment than aesthetic evolution. The high-decibel hijinx, however, remain. Maggie and her sometime-girlfriend, sometime-best friend Hopey spend the bulk of the book fuming, with exclamation points and distorted kabuki-mask faces abounding. Listen, I’ve certainly known people who’ve spent years and years dancing around their true feelings for each other, but never so loudly! It’s like a soap opera scripted by Fourth World-era Jack Kirby! When quieter characters like Hopey’s ex-girlfriend and current bandmate Terry or witchy, death-haunted Izzy appear, I swear I can hear my ears ringing in the relative silence.

If Jaime has a claim to greatness in these pages, it’s in his creation of those two comparatively minor characters. Terry Downe looks so much like The Amazing Spider-Man‘s Mary Jane Watson that she might as well be a fanfic version of her: “What if Gwen Stacy had lived, and M.J. moved to California, got into punk rock, and became a lesbian?” But behind her resolute, John Romita-derived wall of punk cool, there’s just oceans of pain, observable both in her relentless quest for musical success (given what we know of her, this may well be possible) and for Hopey (given what we know of Hopey, this isn’t). She’s easily the book’s most compelling character, and the story in which she stars, “Tear It Up, Terry Downe,” is easily its most compelling sequence. With alarming proficiency not in evidence elsewhere in the book, Jaime constructs a riveting story out of disjointed panels, each depicting a scene from different stages in Terry’s life or a comment from someone who knows or knew her, each offering a vital glimpse of the origins of her reserved persona. Clearly, it’s one born out of trauma rather than pretension. (Would that this could be said for the object of her unrequited love: Hopey’s early relationship with Terry is undoubtedly tumultuous, but it feels as though this simply brought out obnoxious qualities in the character that were already extant.)

Black-clad psychic Izzy is also a revelation. Her premonition of disaster in “The Death of Speedy Ortiz” is the truly haunting moment in a story I found to be otherwise quite oversold by its admirers (who are many, and vocal); her fascination with the missing-persons ad Hopey eventually finds herself on is equally memorable, as is her quietly built-up battle with cancer, and indeed the simple presence of her stoic countenance in a book that’s full to bursting with mugging. But Izzy’s great shining moment, “Flies on the Ceiling,” isn’t even included in the collection. Meanwhile, a zany, Warner Bros.-style Maggie’n’Hopey romp redrawn from a comic made when the brothers were little kids is included, proving that the parameters of the collection — “The Maggie and Hopey Stories” — may have been more than a little short-sighted.

Jaime’s technical skills as an artist are not to be scoffed at, obviously. This is a beautiful book. Each of his characters is a wonder in design, and even as Jaime’s style shifts from the rendered EC-isms of the early stories into a sort of graphic-design shorthand by book’s end, you simply have to marvel at his skill in creating recognizable characters who maintain their essence through over a decade of hairstyle and hair-color changes, weight gain and loss, and radically shifting stations in life. (This last, too, is a strength of the book: Locas is one of comics’ more interesting explorations of the simultaneous fluidity and rigidity of America’s class-and-race caste system, all the more so since the topic seems to get explored almost incidentally.) The art’s strongest moments come during several pin-up style panels depicting Hopey and Terry’s band on stage during their ill-fated tour. Simply put: If there are better depictions in this medium of the allure of punk rock than the page-spanning panels in “Jerusalem Crickets 1987,” I’d like to see ’em. Too bad that so few of the characters seem to have gotten much more out of punk than an excuse to act like jerks and push their loved ones away — and too bad we’re supposed to think that the band’s drummer is an idiot for wanting to play like John Bonham. Odd that an artist’s love of technical proficiency would be mocked in a Jaime Hernandez comic!

Meanwhile, Jaime’s temporal jump-cuts demonstrate a wonderful faith in the intelligence of the reader to follow the increasingly complex lives of the characters. The problem here, though, is that the characters lack the strength of characterization to back these jumps up. As presented within Locas, too many characters suddenly appear from nowhere and are given prominence that their development itself won’t bear. The character of Tex, for example, emerges suddenly to become a pivotal player during some of the book’s central stories: He helps Hopey escape from her band’s rapidly imploding tour, then ends up impregnating both Hopey and her larger-than-life trophy-wife friend Penny Century before just kind of petering out of the storyline. Now, I can already hear people say “but this is how life works,” and indeed I’ve got a roster of ex-friends as long as your arm to prove it, but life also includes two hour visits to the DMV. Trueness to life is a potential means to the end of great art, not a guarantor of it. (At any rate, few people’s true-life trajectory involves knocking up two lipstick lesbians in one of said lipstick lesbians’ so-big-there-are-whole-wings-no-one-sets-foot-in mansion, owned by said lipstick lesbian’s horned husband.) A natural-feeling rapport between familiar and out-of-nowhere characters can be established — see Ralph Cifaretto’s introduction in The Sopranos, Wolverine’s conversation with Doop in Milligan and Allred’s X-Force (I shit you not), or really any such incident in Palomar — but in Locas the continuous accrual of sisters, cousins, roommates, co-workers, ex-girlfriends, bandmates, tag-team partners and so on feels forced and arbitrary, and at its worst like a convenient distraction from the voids at the centers of the two main characters.

That, too, is the problem. Yes, I’m sure we all know basket cases like Maggie and angry youth like Hopey, but so what? I also know several people (say) with masters degrees in engineering, and if they weren’t also interesting people, no degree of accuracy in the depiction of their lives would save a comic I might make about them from being rather pointless. Near as I can tell, there’s simply not much to Maggie and Hopey. The funny thing is they are so very often held up to be the pinnacle of multi-dimensional female characters in the male-dominated world of comics. Now, I’m not sure I see the feminist victory present in the ongoing chronicles of beautiful, bed-hopping, punked-out teenage lesbians; otherwise I guess we could all trade in our P.J. Harvey records for those Tatu girls. (And let’s not even get started on Penny Century, a character whose sole purpose seems to be to conveniently deploy her tits, mansions, or both, depending on the needs of a given story.) But even putting all that aside, what is so wonderfully multi-dimensional about a girl who is continuously pining, fuming, or (to steal a line from Tina Fey’s Mean Girls) eating her feelings, or a girl whose sole, and I do mean sole, means of interacting with the world is to embrace terrible behavior on the part of herself and those around her toward anyone she might be tempted to care about? The torpedoing of one’s own chances at happiness is often a fascinating topic for comics, yet only if the character doing the torpedoing seems to have some inner life worth preserving does that fascination arise. Hopey, a character who among other things bounces back from a miscarriage like it was the common cold, ostentatiously applauds the sexual depravity of a group of wealthy acquaintances until it inevitably erupts into violence, kicks the snot out of her ex-best friend for no good reason, and (during a flashback) delivers her new friend Daffy into a terrifying encounter with an unhinged, nymphomaniacal pro-wrestler just for gits and shiggles, does not have such an inner life. Hopey is at her most interesting in the story “A Date with Hopey.” Told from the point of view of a character that we never see before or again, it describes the instant rapport like-minded, alienated youth feel for one another, and the mysterious way in which such instant closeness evaporates. With Hopey, evaporate is all it can do. (Maggie, saddled as she is with years spent in love with this woman, is rendered uninteresting by osmosis.) Like Daffy after that pro-wrestler flashback, we’re left wondering: Is the woman we’ve spent years (or the page-count equivalent thereof) questing after like some combination of Dulcinea and Moby Dick really just kind of a boring asshole? And has punk — along with Latino culture and professional woman’s wrestling, milieus Jaime chronicles with a great deal of self-evident passion and love — taught her anything aside from how to be professionally unpleasant, to the detriment of herself, her friends, and us readers?

A little over a year ago, before the release of Palomar and Locas rendered such questions irrelevant, I wondered where was the best place for a Love and Rockets neophyte to start reading the series. As a result I posted a thread to this publication’s Internet message board, entitled “Help me learn to like Love and Rockets.” The gist of the post was this: As a stickler for reading any given series in the chronological order of its release, I’d found myself stymied at the logical starting place, Music for Mechanics, which I’d tried and failed to get through three or four times now. My hope was that an alternate option would be proposed. Little did I expect the combination of bafflement, indignation and fury that would be aimed in the post’s direction. Though I did receive a number of considered and considerate recommendations, the general attitude displayed by the board toward those who had not already pledged allegiance to Los Bros could be likened to those T-shirts you sometimes see straightedge hardcore kids wearing, the ones that say “If you’re not now, you never were!” If I didn’t already love Love and Rockets, if I didn’t already see why it deserved its two decades of plaudits, it’s probably best if I just shut the fuck up about it. In other words, “If you’re not now, you never will be!”

I wanted to like the Maggie and Hopey stories as much as I was supposed to. I wanted to let the strength of “Tear It Up, Terry Downe” and “A Date with Hopey” and parts of “Chester Square,” “Wigwam Bam” and “The Death of Speedy Ortiz” convince me of the near-messianic value of the volume’s remaining 650 pages. But in the end, maybe Maggie, Hopey, and Jaime’s whole half of L&R are like the early gigs of the band Ape Sex that the pair reminisce over, heaping scorn on those who weren’t in attendance. Maybe you had to be there.

Comics Time: Batman: Knightfall Part One: Broken Bat

September 29, 2010Batman: Knightfall Part One: Broken Bat

Chuck Dixon, Doug Moench, writers

Jim Aparo, Jim Balent, Norm Breyfogle, Graham Nolan, artists

DC, 1993

272 pages

$17.99

(Originally published on April 18, 2009 at The Savage Critic(s))

Knightfall was the big Batman event during my time as a comics reader in the early to mid ’90s. That basically means it was the big superhero comic event for me during that time. Batman was the character that got me reading comics. The first Tim Burton movie sparked my interest in the character, and The Dark Knight Returns–the first comic book I can actually remember reading–cemented it. The comic shop I went to was called Gotham Manor, for pete’s sake. And so, a multi-series crossover pitting Batman against basically his entire rogues gallery until some hulking brute takes advantage and breaks his back? Yeah, sign 9th-grade Sean Collins up. But how does it look now?

Unlike most of the straightforward superhero comics I read during that time, I actually remember Knightfall, and remember it fondly at that. This is not to say it doesn’t suffer from all the shortcomings you’d expect. The dialogue, the clothing designs, the hairstyles, especially for anyone we’re supposed to think of as “cool”…you almost wonder whether early-’90s DC writers and artists ever had any contact with the outside world at all. The book is also deep, deep in the shadow of Dark Knight, and not just in the obvious grim’n’gritty way; it occasionally serves up ersatz versions of Miller’s satire–a pop psychologist called “Dr. Simpson Flanders” hawking his book I’m Sane and So Are You! and glibly defending the rights of the escaped Arkham Asylum inmates, for example–with none of Miller’s sharpness or genuine comedic sense. Despite the overwhelming tonal debt to Miller and Burton, the character designs and color palette remain incongruously bright and buoyant. And while the newly created archvillain Bane cuts an impressive figure despite his many detractors at the time, the less said about his perfunctory posse of villain types (bird guy, knife guy, tiny brick) the better. This comic is not one of my favorites in the way that Black Hole is one of my favorites, in other words.

But! The book still somehow remains exactly what a big crazy Batman event should be. For one thing, it’s got that inner-eight-year-old appeal: What Bat-fan wouldn’t want to see Batman tangle with all his big enemies in rapid succession, with some minor ones given impressive tweaks and thrown into the mix for good measure? The very nature of Batman’s rogues gallery–75% of them spend their days right next to each other in a row of cells in Arkham Asylum, allowing both the comic and your imagination to pace the hall and peruse them like a set of action figures on the shelf–taps into a childlike desire to see a bunch of cool characters one after the other, and the story takes full advantage.

But it’s not just that Knightfall shows Batman fighting the Joker, Scarecrow, the Riddler, Killer Croc, the Mad Hatter, the Ventriloquist, Firefly, Zsasz, Poison Ivy and so on all in a row–many subsequent storylines, for both Batman (Jeph Loeb’s Hush) and other characters (Mark Millar’s Spider-Man), have gone back to that well with diminishing returns. Knightfall clicks because, as far as Batman comics go, it makes sense. If I were some criminal mastermind who wanted to take over Gotham and fuck Batman up, blowing a hole in Arkham Asylum and freeing all the crazy supervillains is exactly what I’d do. Meanwhile, if I were Batman, taking on all my crazy supervillain enemies in a row really would wear me down to the point of exhaustion. To Dixon and Moench’s credit, the labors they put Batman through are such that they emphasize the physical toll Batman’s heroic activities would have on his body. During one fight, he has to leap his way through a burning amusement park; during another he has to carry the wounded mayor through a flooded tunnel; he does an awful lot of hand-to-hand combat with guys with swords and knives or guys twice his size. And keep in mind that this is the Jim Aparo-era Batman, not a Frank Miller tank or a Jim Lee splash-page pin-up. He has a sinewy swimmer’s body that you can practically feel getting pummeled. His downfall–ahem, Knightfall–is perfectly plausible.

Then there’s the ending. Ninth-grade me wound up so upset about Bruce Wayne getting replaced that I stopped reading with that issue with the die-cut Joe Quesada cover where the new armor-clad Batman takes Bane down; the bad guy got his comeuppance, and that was enough of that for me. I’ve since managed to track down most of the KnightQuest and Knight’sEnd material that followed, and it seems to me that the mega-event couldn’t keep up the manic intensity of this opening arc. So in that sense, having Bane break Batman’s back so that a new guy could take over may not have amounted to much. But as an image? One of the highlights of the ’90s in superhero comics, certainly. Say what you will about Bane and Doomsday, but people remember them not just because of what they did (if that were so, everyone would remember all the Clone Saga bad guys too), but because of the memorable way in which they did it. And after issue after issue of histrionic overwriting, it’s how simple the end winds up being that makes Bane stick: There’s the famous splash page of Bane snapping Batman’s spine over his knee, followed by the words “Broken…and done.” After all this crazy build-up, Batman goes out like a sucker, and Bane drops him on the floor like garbage. It’s almost the opposite of the big final simultaneous punches that enabled Superman to “die” a hero. It’s appropriately more morose.

Knightfall is a book I return to often, but not to read. I flip through it, skimming a passage, checking out an image, slowly going through a sequence. The execution may often be wanting, which makes going page by page a slog, but the basic ideas are sound as a pound and a delight to light upon. When I’m in the mood for raw superhero action and thrills, there aren’t many books I like better.

Comics Time: Dark Reign: Zodiac

September 27, 2010Dark Reign: Zodiac

Joe Casey, writer

Nathan Fox, artist

70 pages

in Dark Reign: The Underside

Marvel, 2010

256 pages

$24.99

Here’s a fun, nasty, wonderful-to-look-at comic about letting your freak flag fly, even or especially if that means murdering people. Yes, writer Joe Casey, who at this point has carved out a career in comics by dancing between other writers’ raindrops–he can afford to, since as a honcho at the studio that created Ben 10, he’s the one making it rain most of the time–is doing one of those “charismatic villain makes vaguely philosophical points about anarchy and society and shit while blowing stuff up” stories. And strangely, it works!

I think that’s because Casey keeps it so rooted in a villain-vs.-villain context, specifically the “Dark Reign” event Marvel did, in which former Green Goblin Norman Osborn assumed control of America’s defense, intelligence, and superhero infrastructure. Zodiac, who as best we can tell is just a guy in a suit with a bag over his head for a mask, sets out to be (in John McClane’s memorable description) “the fly in the ointment, the monkey in the wrench, the pain in the ass.” It’s not just that killing people represents the ultimate act of a free man in an existentialist world or something like that–it’s that seeing a one-time whackjob who rode around on a glider dressed as a goblin with a purple nightcap throwing pumpkin bombs at people suddenly become Donald Rumsfeld offends his sensibilities as a proud supervillain. That’s a way to sidestep the been-there-done-that philosopher-killer thing and bring out the fun of watching different bad guys smack each other around, something superhero comics can always do well.

It also helps that Zodiac’s design and raison d’etre owe so much to Christopher Nolan’s uber-popular Batman movies: He’s basically just Heath Ledger’s Joker dressed up like Cillian Murphy’s Scarecrow. Heck, Zodiac kicks things off by painting a sloppy smiley face on his mask (in blood, of course), and in the final issue all but quotes Ledger’s Joker: “What is being a super villain if not living a life of no rules?!” Why, he even blows up a hospital! (He also has scars, though he doesn’t ask anyone if they’d like to know how he got them.) Casey barely needs to paint in broad strokes, since we’ve already seen this particular painting. We can just revel in the Neveldine/Taylor-style grand guignol mechanics of it.

That’s where Nathan Fox comes in. Casey’s work has its adherents, but as with any writer, his stuff works best when he’s paired with a grade-A stylist. (Cf. Frazer Irving in Iron Man: The Inevitable.) Fox is certainly that. His work owes a great deal to Paul Pope’s, clearly–it takes Pope’s “What if ‘Guernica’ were a science-fiction action spectacular?” approach, dials down Pope’s Romanticism, and dials up the raw, testosterone-packed spectacle of it all. Considering how much ink is being slung around here, it’s really quite impressive how easy it is to parse both the action scenes (the Human Torch’s doomed attack on Zodiac’s goons is every bit as propulsive as a Human Torch attack ought to be) and the pacing (a scene at the Torch’s hospital bed flashes back to the attack and forth to his super hero visitors effortlessly). His character designs are a lot of fun, too: I’d imagine future Zodiac appearances will be made possible simply by Fox’s memorably rumpled take on him here, for example, while the existing heroes and villains we see–Torch, Ronin, the Wasp, Osborn’s Iron Patriot armor–stay on-model just enough for us to be able to appreciate the way Fox coaxes out the weirdness and aggressiveness of their original designs.

I also want to draw special attention to the colors of Jose Villarubia. It’s not just that they’re bright, buoyant, and practically glow off the page, particularly any time fire or explosions are required (which is often). It’s that flipping through the comic once again just now reveals an overall scheme at work: The heroes, represented by the Fantastic Four, usually appear in a world of blue, while Norman Osborn is red–as are the Torch and the giant robot Zodiac uses as a decoy at one point, i.e. the characters who engage in direct physical combat. Against these primary colors stands Zodiac, a dark and dingy brown and gray presence who eventually, for reasons I won’t spoil but which have to do with Marvel continuity minutiae so they’re probably not spoilerable anyway, glows with a sickly green. You don’t have to have read very many Vertigo comics to understand that that palette is supposed to represent edgy, grown-up concerns–it’s a simultaneous salute to and parody of Zodiac’s self-conception as the superior force to the brightly colored heroism and law’n’order ass-kicking represented by the prevailing order of heroes and villains. Which is something we’ve seen before, a lot, to be sure. But it’s fun to see again in this case, and fun is what matters.

Comics Time: The Whale

September 24, 2010The Whale

Aidan Koch, writer/artist

Gaze Books, September 2010

64 pages

$10

If his own Xeric Grant-funded book Young Lions and this inaugural release for his Gaze Books imprint are any indication, cartoonist and newly minted publisher Blaise Larmee could certainly do a lot worse than cranking out tastefully designed, inexpensive perfectbound softcover books with brightly colored covers containing softly pencilled, elliptically plotted comics about longing for however long he feels like doing so. Even with all the vitality artcomix has right now, this is an underserved aesthetic, overwhelmed by inkslingers whose work tends to be either tighter and angrier or choppier and wilder. I’d imagine that this material is going to click hard with a group of people who just aren’t getting the comics that might speak to them elsewhere.

I’m not sure how hard it clicked for me, for whatever that’s worth, despite it being a really lovely comic I’m glad I read. In a weird way the lettering, of all things, gives the game away in terms of why this story, of a young woman coming to terms with the death of her partner (whose gender is unclear, and unimportant), didn’t hit me the way it might have. (Or the way Anders Nilsen’s comics on this topic, for example, actually did.) Stick with me for a minute here: Koch draws like a slightly beefed-up version of Larmee–her sensuous, slightly tremulant line shored up by more detailed and realistic figurework and portraiture and a more frequent, textural use of light and dark grays. She has a knack for using filmic techniques like eyeline matches–between her main character and her tiny, adorable dog, to name one memorable example–to make panel transitions pop. And many of those panels are strikingly, intelligently composed: I’m fond of a splash page of boats along a dock at the bottom of the page, the water filling the rest of the page with just a few suggestions of waves and ripples, which echoes a similar “shot” of our protagonist’s bare feet protruding from the bottom of the page as she looks down at a rug partially covered with boxes of her late loved one’s possessions. We get bird’s eye views, seal’s eye views, close-ups, panoramas, and through it all the sense that we’re not just seeing some figures move back and forth in tiny boxes someone drew, but that we’re in a world someone inhabits, and which that someone colors and contours with her emotions and thoughts. It’s confident comics-making.

Then there’s that lettering. It’s not unpleasant, don’t get me wrong–nice simple all-caps block hand-lettering, in pencil, slanting slightly forward. It’s just that relative to the size and tone of the drawings, it’s a bit overwhelming. The handwriting might obscure that everything’s being said IN ALL-CAPS ITAL, but that’s what it is, and it wrings a lot of the nuance and quietness out of the emotional content of the words. This in turn draws attention to how several of the story’s beats are, if not cliches, then at least familiar to anyone with a passing knowledge of the literature of loss. Boxing up their stuff, grabbing/being grabbed by certain memorable possessions; survivor’s guilt (“THEY SAID I WAS THE LUCKY ONE“); the soothing and saddening presence of the sea; the fairly on-the-nose metaphor to which the title refers, and so on. It’s grief in all-caps ital, if you will.

This, perhaps, is a weakness of this style: losing sight of the fact that feeling something intensely is, in itself, value neutral. How you express it counts more than that you express it. There’s one genuinely moving bit here where that’s clear: The protagonist calls for her dog, and the second time she does so her word balloon has suddenly sprouted another tail, pointing to a ghostly figure who once would have done the same. It’s a killer detail, unexpected and immediately powerful. It’s worth more than any all-caps emotion.

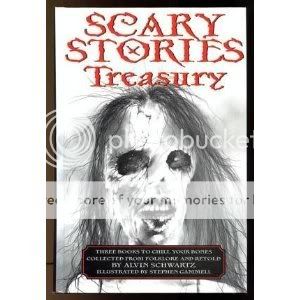

Not Comics Time: Scary Stories Treasury

September 22, 2010Scary Stories Treasury

Alvin Schwartz, writer

Stephen Gammell, artist

HarperCollins, 1995

115 pages, hardcover

$9.95

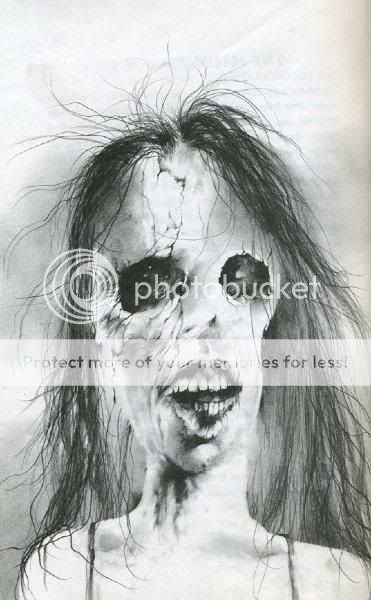

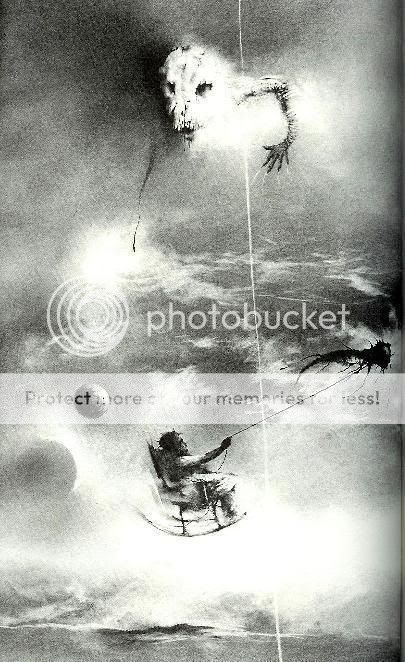

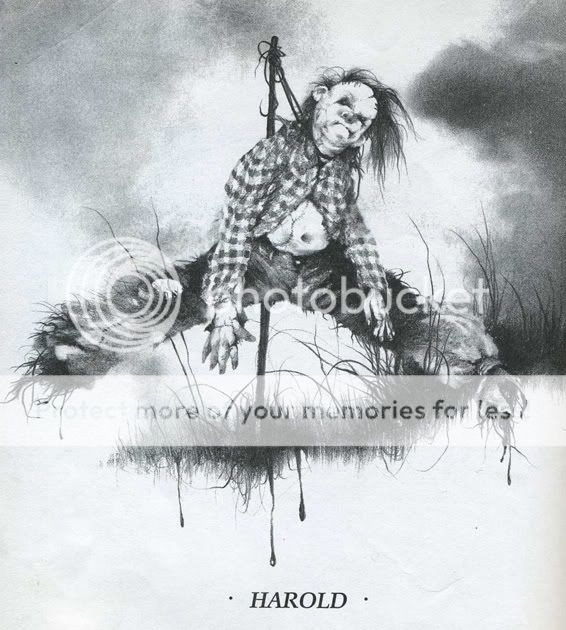

It was a red-letter day when I snagged this omnibus edition of the three collections of scary stories from folklore assembled and retold by Alvin Schwartz and illustrated by Stephen Gammell: 1981’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, 1984’s More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, and 1991’s Scary Stories 3: More Tales to Chill Your Bones. Honestly, I could skip this review and just post the collection of Gammell’s world-beating brain-searing images I gathered up from the Internet, and any point I’d have tried to make would probably be made at least as effectively. If you ever came across these books as a kid, you probably, and this is no joke, remember some of these illustrations better than the faces of your best friends. Like a proto-Al Columbia, veteran illustrator and Caldecott Medal winner Gammell found a way to depict a kind of evil that seems to have seeped into and corrupted those depictions themselves. Instead of deconstructing these images like Columbia does–using sketches, abandoned work, damaged or destroyed pages and so on to suggest that these things almost too horrible to truly commit to paper–Gammell uses washed-out black and gray inks to suggest forms slowly coalescing into being from…someplace else, someplace we can’t fully see and wouldn’t want to. On the memorable occasions when he comes right out and draws these things where you can’t help but look at them, and seemingly they at you, it can quite literally be difficult to sustain that gaze. I defy you to stare at this image, for example–astutely chosen as this omnibus collection’s cover; no effing around here!–without eventually just shaking your head and saying “Jesus.”

But Gammell is equally adept, and just as haunting, when he’s not depicting anything in particular. In a few memorable pieces–sometimes in illustrations for the front matter, sometimes for the stories themselves–he goes full-on black-psychedelic, creating images that suggest surrealism but which replace the traditional visual punning of that movement with disconcertingly decontextualized tendrils and splatters and parts of leering, screaming faces. My favorite of these is the below illustration, for the story “Oh, Susannah!”

Which leads me to the storyteller, Alvin Schwartz. A folklorist with dozens of collections under his belt, Schwartz displays here what I imagine to be a hugely underrated and underremembered proficiency with his prose. These are books for children and young adults, but Schwartz uses that to his advantage. In his best moments, he takes the economical prose typically used to communicate to these age groups–that “So-and-so was a person and this is what happened to him” factuality–and employs it to tell stories of not just the unexplained, but the unexplainable. Again, “Oh, Susannah!” is my favorite. A college student names Susannah comes home late at night and tries to go to sleep, only to be awoken by her roommate, already in bed, singing the old Stephen Foster song. When she switches on the light to confront the roommate, she discovers that the roommate’s head is missing. The story ends with Susannah telling herself “I’m having a nightmare. When I wake up, everything will be all right….” Who murdered the roommate? How long ago did it happen? If the roommate is dead, who was singing the song? Is Susannah having a nightmare? Will everything be all right? What does any of this have to do with the cosmic hellscape with which Gammell has adorned this story? We don’t know, and Schwartz’s all-business prose offers us no comforting room for interpretation. It is what it is, and what it is is horrifying.

Schwartz’s technique can make even the collections’ most familiar stories freshly disturbing. Consider his take on the old “the call is coming from inside the house” urban legend that gave rise to When a Stranger Calls. Here’s how he ends it:

Just then a door upstairs opened. A man they had never seen before started down the stairs toward them. As they ran from the house, he was smiling in a very strange way. A few minutes later, the police found him there and arrested him.

As adults, we know what might cause a stranger who’s spent the evening hiding in a house, menacing a babysitter and the three little children she’s been watching, to smile in a very strange way. Indeed, Schwartz states repeatedly, in introductions to the volumes and chapters and in the notes and sources sections at the back of each volume, that scary stories about the non-supernatural are a way for young people to warn each other of the dangers the real world contains once they leave the protection of their parents–a homeopathic remedy for all-too-real fears, if you will. But within the context of the story itself, the man’s motives and bizarre behavior–that strange smile, his apparent lingering long enough for the police to “find him there and arrest him”–is a mystery, both tantalizing and repellent. It’s up to the young reader to fill in the blanks, and nothing good’s going in them.

But it’s also worth noting that Gammell and Schwartz display a sly sense of humor in a lot of their work here as well, befitting the funny-scary tone of a lot of these summer-camp and tall-tale-derived stories. I’m thinking of the subtly grinning alligator with the human hand who accompanies a story of shapeshifting swimming fanatics that ends with the sentence “Everybody knows there aren’t any alligators around here.” Or of the juxtaposition of the extravagantly bloody, elegantly gesturing hand that accompanies “The Ghost with the Bloody Fingers” with the downright goofy story itself, which ends with a guitar-playing hippie obliviously telling the sanguine specter to “Cool it, man! Get yourself a Band-Aid.” This stuff works as a relief valve for the out-and-out scary stuff, obviously. But it also shows just how deft both writer and artist are in treading that liminal area–between funny-weird and funny-haha, between fact and fiction, between popcorn-spilling scary and afraid to get up and go to the bathroom at night scary–where all these folk tales dwell.

One last thing: Schwartz comes up with the best titles! Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark itself is brilliantly matter-of-fact, but the section and story titles really get good in vol. 2: “When She Saw Him, She Screamed and Ran,” “Something Was Wrong,” “A Weird Blue Light,” “Somebody Fell from Aloft,” “She Was Spittin’ and Yowlin’ Just Like a Cat,” “When I Wake Up, Everything Will Be All Right”…More Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark is the best collection of titles this side of early Gang of Four–just one more delight to be found in this treasure of a book.

Comics Time: The ACME Novelty Library #20

September 20, 2010The ACME Novelty Library #20

Chris Ware, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, September 2010

72 pages, hardcover

$23.95

What makes a life? Is it the narrative we assemble in retrospect from the sights and sounds we remember best? Is it like comics in that regard, a combination of words and pictures stacked together to tell a story? To what degree do we act as our own cartoonists, then, picking and choosing the right combination of words and pictures to tell the story of ourselves we most want to hear? Is it possible that the way we misremember things tells us more of that story? What about the words and pictures we skip entirely? When we come to a point in the story that makes us think “Wait a minute, shouldn’t we have seen Event X or Y or Z by now, why did we skip that, shouldn’t that have been a bigger deal,” what does that tell us? What does a jump cut mean? What does an absence mean? Or what does a presence mean? What do we make of recurring marginalia that pops up when the story is supposed to be dealing with something entirely different? Is that persistence a reflection of the original absence? And who are the characters in our story? Is it fair to see them that way? Do they have any idea that’s what they are to us? Do they know how big a role they play? Do we know how big a role we’ve played in their stories? Would we even remember? Would we ever have known in the first place, or did we forget? How does it feel to find out? How do their stories affect our own? What happens when they leave our story? What happens when we leave theirs? What gets in the way of our own story? What constitutes static on the screen, blots out the image as it really is and makes it something else, however briefly? What do we do and say and think and feel in those moments that’s different from all the other moments? In what new direction will those moments send our story? What happens when we prefer the way the story used to be told? What happens when we find ourselves in a new story of someone else’s making? What happens when a turn of a page to a new set of words and images stuns us, hurts us? What happens when we reach the end of the story? What makes a story worth telling? A life worth living? Looking back, can we ever be sure that the answer isn’t “nothing”?

Comics Time: Incredible Hulks #612-613

September 17, 2010Incredible Hulks #612-613

Greg Pak, Scott Reed, writers

Tom Raney, Brian Ching, artists

Marvel, August-September 2010

32 story pages each

$3.99 each

When I talk about how Batman is the only superhero for whom I feel affection outside or beyond the quality of the Batman comic currently in my hand or movie/TV show currently on my TV, that’s not quite true. Years before I got into Batman, my childhood (and I mean young childhood, barely remembered fuzzy pool of memories out of which pops the occasional actual memory) favorites were, thanks to a back-to-back hour of Saturday morning cartoon programming, Spider-Man and the Hulk. But I think my continuing fondness for the Hulk, at least, stems from his being the superhero metaphor to which I most closely relate. First of all, huge green dude punching things is the superhero concept boiled down to its strongman essence. Secondly, mild-mannered smart guy who smashes anything that makes him angry? Sure, I’ll eat it. But best of all, the consequences of that superpower are built right into the concept. He might be able to put it off by becoming ruler of some planet someplace, or forming a surrogate family of super-goons, but ultimately the Hulk will always be an outcast, always unwanted, always on the run. If Spidey’s thing is “with great power comes great responsibility,” the Hulk is a cautionary tale about what happens when great power is used irresponsibly.

So I dig the Hulk. More specifically, I dig a lot of what writer Greg Pak has done with the Hulk. His Planet Hulk saga showed an admirable attention to detail in building the sci-fi space-opera world, aliens, and cultures through which an exiled Hulk cut a swathe on the road to becoming ruler of the planet. His subsequent World War Hulk event took the kind of concept that would make a third-grader say “Awesome!”–the Hulk vs. the Marvel Universe–and tied it to both killer fight scenes for John Romita Jr. to draw and an exploration of whether the ends justify the means and the extremes to which grief and rage will push us. After that, though, the Hulk disappeared from his own title, which became a road movie starring a de-powered Bruce Banner and his alter ego’s barbarian alien son Skaar, and then everything got tied up in a huge multiple-title roundelay of crossovers and spinoff miniseries and so on.