Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Beyond Palomar

November 5, 2010 Beyond Palomar

Beyond Palomar

(Love and Rockets Library: Palomar, Book Three)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

256 pages

$16.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

If all that Poison River were was dense, that would be one thing. We’ve already seen how far Beto has been willing to push his pacing over the course of discrete sequences like that climactic bit in “Human Diastrophism”–jumps in space, jumps in time, jumps in storytelling and story logic. Doing this for 180-odd pages, to the point where uninterrupted stretches of story bridged either by cuts involving a recognizable end for one scene and beginning for another or by some sort of visual signifier of a transition becomes the exception rather than a rule, is a tour de force performance to be sure, but it needn’t necessarily be a shocking one.

And if all Poison River were was brutal, that would be one thing. Beto has done bleak before–it was the exceedingly bleak Israel spotlight strip at the end of Heartbreak Soup where the Palomar stuff really came into its own, after all. And he’s done brutal (the murders in “Human Diastrophism”) and sordid (Israel’s mercenary hedonism) as well. Creating a story that can basically be described as “Luba’s Adventures Among the Worst Motherfuckers on Earth” can make for a grueling read, absolutely, but it needn’t necessarily be a stunning one.

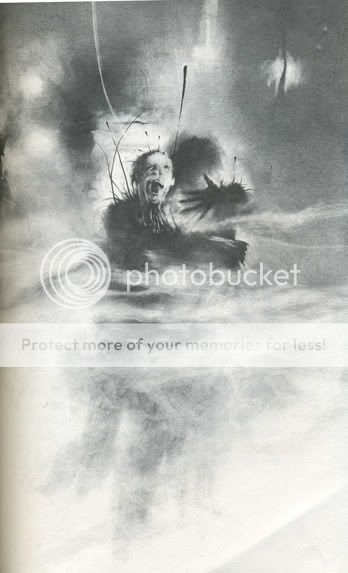

No, it’s the combination of form and content, style and substance that makes Poison River–the graphic novel-length “origin of Luba” story that comprises this collection’s first two-thirds–one of the most singular, potent, unforgettable comics ever made by anyone, ever. When there are more characters involved in the story than in the entire Palomar mythos thus far; when their stories involve a complex web of conspiracies and betrayals, deceptions and secret affairs, over the course of multiple generations; when virtually no page has fewer than seven tightly gridded panels and most have nine or more; when those panels are filled with Gilbert’s never-stronger sooty, inky linework and character designs, which virtually never serve up the sort of iconic imagery that allows you to quickly scan and move on; when each move from one panel to the next holds the promise and threat of feeling more like a page turn or a chapter jump than a simple “and then, and then, and then”; when that feeling lasts not just for a single bravura sequence but for the longest story Beto has yet told; when it’s a story that regularly invokes such brain-lacerating topics as rape, miscarriage, racism, domestic violence, and torture; when it repeatedly slams your heart into scenes of utter cruelty and your genitals into scenes of pure depraved sexuality…It’s like your brain has to spend the length of the story running as fast as it possibly can to keep up, and every so often you run full tilt into someone swinging a baseball bat. You can’t just lie there and shake it off, you’ve got to leap back to your feet and resume sprinting, even though you know you’ve got no hope of not being knocked flat on your ass again.

I’m trying to focus on the emotional response, the feeling, of reading Poison River because, frankly, it’s so overwhelming. But intellectually, I think this is Gilbert’s meatiest work as well. I’m fascinated by how willing he is to lay bare some of his work’s most indelible tropes, like Luba’s comically large breasts and all the baggage that comes with them–with the equivalent of a corny joke, no less: They do her no good in a marriage to a man with a fetish for women’s stomachs. Given the fire Gilbert has taken for his visual depictions of women, it’s quite easy to read Poison River as a lengthy meditation on the damage that having a “type” can do, no matter what your “type” is…which means it’s an extremely black take on the whole of human sexuality, pretty much. It’s also a savagely political work, fusing his past examinations of the powers wielded by both body and brain by showing the physical depravity unleashed around the world by the ivory-tower/missile-silo conflicts of Cold War ideologies promulgated in nations thousands of miles away from the action in the story itself. There’s a haunting, recurring leitmotif involving a racist caricature comic-book character, his beatific blackface smile appearing in the background, and occasionally in context-free close-ups, as a symbol of unthinking, commoditized cruelty. Poison River may also be my favorite artistic exploration of hypocrisy, neither overly condemnatory nor in any way compromising, in terms of how it treats being queer: Nearly every character in the book is either financially or emotionally close to someone who isn’t strictly straight, and nearly all of them really don’t care, and nearly all of them would nevertheless punish those non-straight characters for it if doing so became convenient–and some of the punishments meted out are far more perverse than anything the characters being punished would dream of cooking up. The story also takes Luba herself about as far into unlikablity, even irredeemability, as it can go, before literally walking her through a tunnel and out the other side, as she and we shake off the previous events of her life like a nightmare and emerge with a scarred but strong sense of morality. There’s just a fucking lot going on in this thing.

I feel bad about barely discussing Love and Rockets X, the also-pretty-long story that rounds out the collection, in which we follow some of the Palomar characters in racially tense, hard-partying Los Angeles circa 1990. But in a way, it feels like a riff on the same ideas that drive Poison River, simply filtered through the American/urban/musical milieu normally occupied by Jaime. Racism, capitalism, the way we let sex make us into worse people, violence in the name of ideology…it’s all still there, no matter how many people call each other “dude.”

There aren’t very many comics this affecting, that much I can tell you. You can probably count them on two hands with fingers to spare. I would say I envy the people who still get to read this for the first time, but I just re-read it, and here I sit, knocked on my ass.

Comics Time: Mome Vol. 20: Fall 2010

November 3, 2010Mome Vol. 20: Fall 2010

Dash Shaw, Sara Edward-Corbett, The Partridge in the Pear Tree, Josh Simmons, T. Edward Back, Conor O’Keefe, Nate Neal, Michael Jada, Derek Van Gieson, Steven Weissman, Sergio Ponchione, Jeremy Tinder, Aidan Koch, Nicholas Mahler, Ted Stearn, Adam Grano, writers/artists

Eric Reynolds, editor

Fantagraphics, October 2010

120 pages

$14.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

(Programming note: Taking a brief break from LOVE AND ROCKTOBER today as this book hits stores.)

“5 years, 20 volumes, 72 artists, and 2,352 pages of comics”–that’s how the relatively sparse introductory text describes this landmark installment in Fantagraphics’ flagship anthology series, which I believe at this point has produced more pages of comics than any other such English-language effort. It sees a redesign of the series’ iconic cover layout and a quartet of series debuts, from altcomix known-quantities Jeremy Tinder, Steven Weissman, and Sergio Ponchione, plus Aidan Koch. Paul Lynde and Lil Wayne also make their first appearances in the series. So, big shit poppin’ in Mome 20. Good thing it’s also pretty good!

Don’t get me wrong, there’s still the usual stuff I’m not feeling. Nate Neal’s broad schtick, Ted Stearn’s Fuzz & Pluck (despite some wicked crosshatching), and Nicholas Mahler’s anecdotal autobio never amuse me the way they’re supposed to. Conor O’Keefe’s impeccable McKay-by-watercolor riffs remain more lovely than compelling. T. Edward Bak’s biography of explorer and naturalist Georg Steller still comes across as stiff and disjointed despite some hardcore sex in this installment. And Mome newcomer/Ignatz veteran Ponchione’s studied cartoony character designs don’t communicate anything to me.

But what works works really well thanks mostly to bravura cartooning. Dash Shaw captures the awkward performative heterosexuality of an episode of Blind Date in his adaptation, rendered in a TV-screen-glow green and making the most of his tendency to render people as gestures rather than figures. Sara Edward-Corbett crafts a little funny-animal fable about an ill-fated menage that’s her strongest and most emotionally troubling work to date; the more I look at it the more I realize that no one else in alternative comics has a line that emphasizes its line-ness the way hers does. Josh Simmons’s collaboration with The Partridge in the Pear Tree continues to ratchet up the uncomfortable with the introduction of a leering, sweating, quipping Paul Lynde as a protagonist, chased here by a massive, gorgeously colored slug-pachyderm the size of one of the AT-ATs from The Empire Strikes Back; it’s called the Jiggaboo. (Good Lord.) Michael Jada and Derek Van Gieson’s shadowy World War II story begins with a literal bang, one of the most powerfully drawn gunshots I’ve seen in comics. Steven Weissman’s scratchy black-and-white-and-zipatone art actually works better for me in this harsh, slippery story of memory and loss than it does in his humor stuff. Jeremy Tinder is taking his funny-animal stuff further out and getting sharper as he goes, adding in an artcomix influence to boot. Aidan Koch seems to draw poetic twentysomething slice-of-lifers as tenderly and attractively as anyone currently doing that. And Adam Grano encourages us to Free Weezy, always welcome advice. Here’s to 20 more volumes of this occasionally frustrating, occasionally fascinating, always worth reading series.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Human Diastrophism

November 1, 2010 Human Diastrophism

Human Diastrophism

(Love and Rockets Library: Palomar, Book Two)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

292 pages

$14.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

(Programming note: Yes, LOVE AND ROCKTOBER marches on! And I’m sticking with “LOVE AND ROCKTOBER” because “LOVEMBER AND ROCKETS” just sounds kinda goofy. Thanks for sticking with it, thanks for switching blog locations with me, and thanks for your patience with the unrelated-to-the-blog-switchover computer meltdown that screwed up my reviewing schedule last week.)

I know I just got finished explaining that biology is destiny in the Palomar stories. But what struck me upon rereading the material collected in this volume, dominated by the titular story of a serial killer’s stay in the town, is the power of ideas. Not emotional or sexual drives, even, like the web of lust and unrequited love surround Luba’s mother Maria in the suite of stories that forms the second half of the collection, but actual honest-to-god ideas. Tonantzin is literally driven mad — broken — by the late Cold War political apocalypticism of her criminal boyfriend. (He himself is freed from nihilism’s grip by a jailbird religious conversion, for all the good it does anyone.) Humberto is thrown so far off-kilter by his discovery of the avant-garde artistic tradition from the Impressionists onward that the impact, combined with his fear of the killer, drives him to abandon notions of right and wrong entirely in favor of the truth art can express. In both cases, this ends in disaster.

But there’s a counterpoint to the damage these ideas do. Pipo’s success as a designer and entrepreneur is at least as driven by ideas — from the designs she and her siblings create, to her no-nonsense but still thoughtful approach to business and investing, even to her adamant refusal to learn English as a way to defy being fully coopted by American cultural capitalism — as Tonantzin’s self-immolation and Humberto’s life-threatening secret. Similarly, “American in Palomar” Howard Miller once thought his ideas of art and genius allowed him to dehumanize and exploit the Palomarians, until his actual experiences with them revealed what a creep this makes him; now he’s returned to help Pipo and Diana rebuild and restore the town, using the money made from the artistic project that his time in Palomar forced him to rethink.

Maybe I’m just looking for pat connections here, but perhaps this is why Gilbert’s technique takes a turn for the heady here. Think of that climactic sequence in “Human Diastrophism” where over the course of three tightly gridded pages, each panel represents a jump in time and space, forcing the reader to reconstruct the events that led up to each image herself. Think of the entire Maria/Gorgo section, with its massive, unceremonious leaps throughout the history of the pair’s lives and relationship, the exact contours of which constitute as much of a mystery as the sinister events that forced them both into their secret lives. Think even of the almost playful, superhero-universe-style continuity games Beto plays — the implication that the weird animals that surround Palomar, from an eyeball-eating bird to those vicious monkeys to perhaps even those giant, tasty slugs, are the result of experiments by American military scientists; most especially the oblique revelation that concludes the volume (and all of the first run of Love and Rockets) by bridging the lives and worlds of two of the most haunting characters Gilbert and Jaime ever created. If Heartbreak Soup showed us Gilbert the literary comics stylist, Human Diastrophism shows us Gilbert the mindfucker — the Gilbert who’s still with us today.

Two more quick notes:

1) Human Diastrophism is the one point in the entire excellent Love and Rockets Library digest-size reprint program where I actually have something to object to, format-wise. I found the Palomar hardcover somewhat frustrating because it left out Love and Rockets X and Poison River, two stand-alone graphic novels set in the Palomar-verse if not in Palomar itself. But it wasn’t as bad as Locas leaving out short stories like “Flies on the Ceiling,” and at any rate I understood that when you’re talking about adding two full-length graphic novels to an already gigantic book, page count becomes a factor. However, I figured that with the digests, we’d finally get all the Palomar-verse stories in chronological order, so that Palomar Book Two would include “Human Diastrophism” and “Love and Rockets X,” and Palomar Book Three would include “Poison River” and the material originally collected in “Luba Conquers the World,” which marked the end of the first Love and Rockets run. Instead, things are collected pretty much as they were in the Palomar HC, with the “Human Diastrophism” and “Luba Conquers the World” material collected back to back in this volume, and “Love and Rockets X” and “Poison River” taken out of order and placed in Book Three, Beyond Palomar. If Eric Reynolds had a nickel for every time he’s heard me complain about this, he’d have, well, at least two bits, but this has always driven me nuts. I could be wrong, but I think collecting everything in order would have worked just fine in terms of page count, story cohesion, you name it. Human Diastrophism is a fine collection, and in all honesty the material towards the end involving Luba, her mother, her sisters, Gorgo, and their backstory isn’t really any more confusing without having read the intervening stories in “X” and “Poison River” than a lot of things Gilbert does on purpose. But it wasn’t the way the material was first released, it does make things confusing at least to an extent, and most importantly, it gives the back half of this collection a valedictory, bon voyage feel (since that material was the end of Love and Rockets, as far as anyone knew) that comes across as really sudden and jarring. Next time I may manually monkey with the reading order and stop Human Diastrophism halfway through, read Beyond Palomar, and then pick up with the back half of the book. Hey, if I can do this sort of thing for Final Crisis…

2) di·as·tro·phism (dī as′trə fiz′əm)

noun

1. the process by which the earth’s surface is reshaped through rock movements and displacements

2. formations so made

Origin: < Gr diastrophē, distortion < diastrephein, to turn aside, distort < dia-, aside + strephein, to turn (see strophe) + -ism

Thanks, Webster's.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Heartbreak Soup

October 28, 2010Heartbreak Soup

(Love and Rockets Library: Palomar, Book One)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

292 pages

$14.95

(Programming Note: Due to technical difficulties, I was unable to post this review during the regularly scheduled Comics Time slot on Wednesday of this week. This is the first time I’ve missed a Comics Time deadline, scheduled time off aside, in probably two years, and I’m pretty bummed. My hope is to resume the regular MWF schedule beginning tomorrow, but delays or erratic scheduling may continue until the issue is resolved. I apologize for the interruption in service. Anyway…)

The great temptation when discussing Los Bros Hernandez, and it’s a temptation I’ve succumbed to, is to operate under the assumption that they’re both trying to do basically the same thing, only one of them is better than the other at it. Now, obviously, they are doing many of the same things. They’re brothers who co-founded a series they share in which they tell the sprawling saga of groups of (mostly) Latin American (mostly) young adults that unfold over (mostly) real time, dealing frankly with issues of sex, community, and mortality, starring women who are the closest alternative comics have come to generating sex symbols, and utilizing striking black and white art and inventive, challenging pacing. If that’s all you’re going by (and granted, it’s a lot!), then it’s almost irresistible to point to an element you feel one brother has over the other–Jaime’s incorporation of poster-ready design into his visual storytelling, say, or Gilbert’s magical-realist literary panache–and call him the victor.

But a) much as we comics folks love looking at absolutely everything otherwise, it’s really not a “who’d win in a fight” situation, and b) my re-read of Heartbreak Soup has me more convinced than other that the differences between Beto and Xaime are not differences of degree, but differences of kind.

Let’s talk about the art first. This is the arena where Jaime is most frequently said to have it over Gilbert. And indeed, I can happily imagine a day spent doing nothing but looking at drawings of Terry Downe or Doyle Blackburn. That smooth line, those sumptuous, propulsive blacks, those enormously appealing and endearing character designs–it really is eye candy, in the best sense of that term. But a key goal of Jaime’s art, besides being pleasant to look at, is pop. Not in the sense of “pop art,” although I think that’s a major element and not just due to the occasional overt Lichtenstein homage, but in the sense that they pop off the page. Those blacks fill in space in a way designed to sharply foreground the figures and objects Jaime wants you to focus on or remember, something his sharp, slick line abets. When I picture Jaime panels, I tend to picture the characters are arrayed in a line from left to right against some sort of horizontally oriented background like a car or a wall, like actors (or punk rockers) on a stage. Moreover, he tends to draw his characters in poses and facial expressions that come across as, well, poses–the precise moment at which whatever they’re feeling or thinking or saying or doing is communicated most clearly, so that that thing pops off the page. The overall effect is that there’s them in the spotlight, and then there’s the other stuff against which that spotlight is defined.

By contrast, when I picture Beto panels, I picture someone more or less standing around, usually with one or more other characters milling around as well, with the house-lined streets and intersections of Palomar extending out to the back left and back right. The very setting of his stories is one through which his characters are constantly walking to get from one place to another; I couldn’t draw you a map of Palomar or anything like that, but I feel like I’ve been walked through its streets much more than I can say that of Hoppers. Moreover there’s a casual element to Gilbert’s imagery that Jaime’s more compositionally calibrated panels don’t have. Beto’s line is rubbery, and complimented not by masterful fields of smooth, clean black but by shading and stippling that feels almost dusty. His character designs famously overemphasize flaws and virtues alike, and have a uniformly heavy-lidded weight to them; my wife simply describes his characters as “hard.” It’s tough to imagine spending a pleasant few hours staring even at Tonantzin or Israel the way you might at Maggie or Rand Race. And when characters are depicted for maximum impact, it feels like it’s being done through great force of effort on Gilbert’s part rather than with the effortless, effervescent precision with which Jaime does it. It’s also almost always either something the characters in question are doing on purpose to impress someone else, or a shot of them as seen by someone who they’ve impressed unwittingly. The overall effect feels calculated more for immersion than impact.

Then there are the stories and subject matter. One difference is obvious from the start: Jaime had a couple-issue jump on his brother in terms of beginning his magnum opus, but the delay gave Gilbert the opportunity to draw a bright line between his science-fiction work and his (occasionally magical) realist material. But beyond that, Gilbert very rapidly jumps his action forward about ten years or so from the first major story to the next, while Jaime’s almost resolutely marches forward in sync with our own real-world timeline. Jaime presents material from the past largely in the context of memory and how it intrudes upon and influences us; arguably the past’s on-again off-again love affair with the present is even more central to the Locas strips than Maggie and Hopey’s. Gilbert, however, doesn’t usually view stories from back in the day through that psychological lens. They tend to be presented as discreet tales, filling in backstory, spotlighting a character or a relationship, illuminating a part of Palomar we haven’t seen, depicting someone or something lost to time. Jaime’s interest in the past is primarily internal in its effect; Gilbert’s is primarily epic.

Particularly in light of their recent work, there’s another difference between Gilbert and Jaime worth pointing out. Jaime’s work is studded with sit-up-and-take-notice stories, and his most harrowing stuff–“The Death of Speedy Ortiz,” “Flies on the Ceiling,” and now “Browntown/The Love Bunglers”–tends to be among them. But when you hit “The Death of Speedy,” it’s not as though it establishes the tone for the rest of the series. It’s an exception, not a rule. “Locas” tends to be lighthearted even though what it’s really about–friendship, sexuality, identity, adulthood–is actually quite serious.

By contrast, the harshness, seediness, and bleakness of the world of Palomar and of Gilbert’s work generally–the love many of his characters feel for one another notwithstanding–tends to be what first comes to mind when I think of his comics. Yet Heatbreak Soup struck me for how good-natured it feels, up until the very end. Yes, sex is presented from the very first strip as a magnetic force with the potential for incalculable damage, and the book often does feel like “horniness punctuated by the occasional physical assault.” But centering the material on good-hearted Heraclio, unpredictable Luba, and packs of sweetly belligerent little kids and teenagers goes a long way to making everything feel funny, even when you’re not laughing. It’s almost Pueblo Home Companion, you know what I mean?

It’s only when you hit the final story in this collection, “Bullnecks and Bracelets,” that things truly take a turn for the dark: Try as he might to bury himself in bodybuilding, drugs, love affairs, and hustling, Israel’s whole life is defined by the disappearance of his twin sister during a solar eclipse when they were very young. No matter where he goes or what he does, he cannot escape that black sun. And this is where “Palomar” becomes what it is–where Gilbert becomes what he is–as surely as The Sopranos became what it was with “University” in Season Three. Whether in terms of family, sexuality, physicality, or deformity, biology is destiny for the people of Palomar, in a way that is almost never true for the Locas (Penny and H.R. excepted, perhaps–and a certain character in “Browntown”). And although biology is obviously among Beto’s primary concerns, destiny is the operative word. I don’t think the Palomarians have the ability to escape the way the Locas do. Not all of them need to escape, mind you–there’s a lot of really warm and adorable and hilarious and awesome stuff going down in Palomar–but whatever walks alongside them in their lives is gonna walk alongside them till the very end.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #3

October 25, 2010Love and Rockets: New Stories #3

featuring “The Love Bunglers Part One,” “Browntown,” and “The Love Bunglers Part Two”

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

104 pages

$14.99

If I had to sum up all of the post “Wigwam Bam/Chester Square/Bob Richardson” Locas stories in a phrase, it would be “coming to terms.” With adulthood, with the death of punk, with a career, with the past, with reaching middle age, with falling in and out of love, with family and friends and heroes, with your limitations, even with really good things like your talents. (Heck, even this story reveals that Maggie’s planning to open up her own garage, finally utilizing her long-dormant skills as a mechanic.) For the most part this has gone, if not smoothly, then at least pretty well in the end. Maggie and Hopey both seem less prone to disaster than ever before, as does Ray. Yes, Izzy had a fairly spectacular flame-out–literally!–but Ghost of Hoppers nonetheless ended on an optimistic note for her future. Put it this way: No, I wouldn’t be surprised if that was the last we saw of her, if she were lost to mental illness and to us forever, but nor would I be surprised if she came back reunited with her man in Mexico, content and writing again. Penny sort of exploded her way out of the series too, depending on how much credence you give “Ti-Girls Adventures Number 34,” but her story also ended on a note of hope for future reconciliation with her children and repentance for her life of fecklessness. A few years ago, Jaime ended Love and Rockets Mark II with two dueling stories of people making other people feel whole again by virtue of their very presence. What a kindly pair of comics,” I said.

So much for kindness.

The suite of strips that Jaime contributed to this year’s Love and Rockets: New Stories volume, which revolve around the long centerpiece “Browntown,” comprise the cruelest and story he’s ever told. Sadder than “The Death of Speedy,” scarier than “Flies on the Ceiling,” crueler than “Wigwam Bam.” Jaime’s line, which has been loosening somewhat over the course of the last few books (I first noticed it in “La Maggie La Loca”–a de-tightened approach to better accommodate Steve Weissman’s colors), is as limber here as I’ve ever seen it, the closest perhaps he is capable to looking like he drew something in a white heat. In filling in one of the biggest remaining gaps in Maggie’s backstory, the two years she spent living with her family away from Hoppers, Jaime reveals what seems like the key piece of the puzzle of Maggie’s bad luck in love and her punk-era rebelliousness, and a sealed-off well of pain caused by her estrangement from her family. But worse–and I don’t want to spoil anything here, so I’m not even going to say who I’m talking about–it introduces a character who, at long last, can’t come to terms. What happened in this person’s life, through no fault of anyone but the perpetrator but as a result of unwittingly malign neglect by everyone else, broke them, never to recover.

It’s easy enough to tell that sort of story, I suppose, but difficult to make the reader feel an impact of discovery of this tragedy commensurate to what the characters themselves might feel. Jaime’s genius is that he pulls it off, with an out-of-nowhere punch-to-the-gut revelation that literally made me gasp out loud. It’s his “I did it thirty-five minutes ago.” And ever since I read it, when I think of it, I just keep thinking to myself, “Poor [name]. Poor, poor [name].” It makes me want to cry! Cry for an imaginary person I’d never read about until a few pages earlier. (It’s the flipside of feeling proud of the entirely imaginary Hopey Glass for becoming a teacher’s assistant, I guess.) Such power! Between this and the not at all dissimilar ACME Novelty Library #20, this year has featured two of the most devastating–and I mean so sad it impacted me physically–comics I’ve ever read. I will never forget reading this book. Finally, I was there.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets: New Stories #1-2

October 22, 2010Love and Rockets: New Stories #1-2

featuring “Ti-Girls Adventures Number 34”

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2008-2009

104 pages each

$14.99 each

This is going to sound a little weird, but one of my favorite things about the superhero flight of fancy with which Jaime inaugurated this third Love and Rockets series, now in bookstore-friendly post-altcomic squarebound format, is the fact that I was pronouncing the titular super-team’s name wrong nearly the whole time. I was thinking “Tee-Girls”–maybe you can blame the aging super-version of Xochtil’s resemblance to Maggie’s Tia Vicki for putting that pronunciation in my head–when as it turns out its a play on “Tigers.” And whaddayaknow, just like that, Jaime’s imaginary team of misfit superheroines fits right into the very real and very long legacy of superhero characters and creators I’ve heard people completely mispronounce: Namor the Sub-Mariner, Magneto, Sienkiewicz, Quesada, Byrne–not to mention “Jamie” Hernandez himself. Probably just a fluke, I know, but somehow it feels more like attention to detail.

It’s easy to dismiss “Ti-Girls Adventures Number 34” as precisely that sort of pleasant superhero-nostalgia diversion, a chance for Jaime to work directly in the idiom of one of his greatest but least frequently expressed influences. It’s certainly difficult to square it with the Locas-verse as we know it. The wildest left-turn back into the fantastic that the “Locas” strips have taken in probably 20 years, it transforms Penny Century into the mad superhero she’s always dreamed of becoming, reveals that Maggie’s apartment-complex neighbors Alarma and Angel are secretly superheroes themselves (we’d already caught some glimpses of Alarma in costume, but that was in the storyline where we also saw the devil take the form of a levitating black dog, so, y’know, grain of salt), brings sundry superheroes mentioned in the imaginary comics Maggie reads to life (e.g. Cheetah Torpeda, herself the namesake of a strip club Ray D. frequents), features inexplicably aged versions of previously existing characters like Maggie’s wrestler cousing Xochtil, posits the existence of a mutant-like female-only “gift” of superpowers, and ultimately reveals that Penny was never really real to begin with. “I’ve known Penny for quite a few years now,” Maggie says, “and in all that time she never aged. Like, she was not regular flesh and blood, but like, this drawing that was clipped from a comic book and pasted down here on Earth.” And here I’d thought she’d just used H.R. Costigan’s billions to have a lot of work done!

And indeed, Jaime’s art here is so zesty that maybe a chance to have fun with super-powered women in skimpy costumes really is the main point. (And frankly it’d be worth it if only for the debut of Alarma’s glam-rock cut-off-tank-top villain look. Yowza.) The effect he achieves with his black-and-white-uniformed Amazons flying around or smacking each other around against the night sky or in the void of outer space is frequently breathtaking–my dream comic con panel is a “spot-black-off” between him and Mike Mignola. Meanwhile his action choreography is to die for. Witness the knockout wordless nine-panel-grid page in Part Two of the story, featuring a series of images in which Angel attempts to join the fight against an off-the-right-hand-side-of-each-panel Penny Century, only to be rebuffed at each stage by one of the uber-powerful popular girls of the superhero scene, the Fenomenons. In each panel there’s a palpable drive from the left to the right, thanks to motion lines and those blacks, but there’s always something stopping Angel from getting to that elusive border. I know I lecture superhero writers and artists all the time about how they should be doing their job, but, well, this is how they should be doing their job.

But there is more to “Ti-Girls” than meets the eye. Super-Penny turns heel not just because she’s gone mad with power, but because those powers have caused her to lose two of her children; in order to thwart Penny, one of the Ti-Girls uses a ray-gun to zap another with a sample of Penny’s “maternal instinct,” which can be used as a homing device. I think this may be one of the most explicit explorations of motherhood ever for “Locas”; certainly Penny and Hopey’s dueling pregnancies way back when weren’t explored in terms of how the pair felt about the kids they had and/or didn’t have. There’s Tia Vicki’s misery over her belief that Maggie resents her for how she raised her, too, but that didn’t involve birth and babies and very young children like this storyline does. I wonder what it says about Maggie that this is all being processed in something very like a dream?

There’s also an explicit feminist angle. Women are the only people capable of becoming super-powered naturally; they’re born with “the gift,” while men have to try to recreate it with lab accidents or magic meteors or what have you. Meanwhile, the entire history of female superheroes in this world is one of their management and exploitation by one Dr. Zolar–his crowning superheroine-team creation is an all-teen unit, the Runaways to his Kim Fowley. But perhaps most strikingly, certainly if you read regular superhero comics, is what a non-presence male superheroes are. None are drafted into the fight against Penny, and the few we meet are basically non-entities who exist to get thrashed by one of Penny’s super-kids or to help out the Ti-Girls in locating them. The problems in the story–Penny’s rampage, a breakout at a female supervillain penitentiary, a supervillainness out for vengeance, a Bizarro Ti-Girl–are all caused by women, addressed by women, solved by women, and have consequences felt by women. I actually think you might have a hard time getting this comic to pass a reverse Bechdel Rule, in fact. And that’s enormously, enormously refreshing. If “Locas” has taught us anything, isn’t it that women should be the stars and driving forces behind their own damn comic, even if they’re dressing up in one-piece swimsuits and punching each other in the process?

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

October 20, 2010Love and Rockets Vol. 2 #20

featuring “La Maggie La Loca” and “Gold Diggers of 1969”

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

56 pages

$4.50

(First, a quick reader’s note: At this point I’ve read all of the all-Jaime/Locas L&R collections. For this, the final issue of Love and Rockets as a comic-book-format periodical, and for the three currently available volumes of its new squarebound incarnation, Love and Rockets: New Stories, I’m going to be reading and reviewing Jaime’s stuff on its own before starting over at the beginning with Beto. There are other ways I could play this, but I’m enamored by the idea of being all caught up with Maggie and company. And yes, this means LOVEMBER AND ROCKETS is on its way…)

The triumph of the continuity! Leave it to Jaime to use “La Maggie La Loca,” the inaugural strip for The New York Times‘ “Funny Pages” lit-comics section, to address one of the oldest, wildest, most sci-fi strips in his series’ history. Though the more outlandish details are largely (but not entirely–I spy a glowing robot head in one of those flashback panels) elided, Maggie the Mechanic’s adventures in the jungle alongside Rena Titanon and Rand Race are officially not retconned. I’m happy about this because I’m the sort of person who pulls for that early sci-fi stuff, encouraging folks who want to start reading the series to start there even though it’s so different in vibe and visuals from what it ends up being. I’m also happy because it means that Maggie’s translator for that time, Tse Tse, returns for the strip, revealing herself to have become maybe the smartest and most successful of the characters. (I’d always considered her the “lost Loca” and hoped she’d somehow find her way to Hoppers or the Valley.)

The strip’s story involves Maggie receiving an invite to come visit Rena on the private island where she hides from the admirers and enemies she made during her dual careers as a wrestling champion and a revolutionary icon. Maggie, of course, is just a humble apartment manager, and she spends most of the visit alternating between awe, jealousy, and contempt for her hostess, whose glamour and strength appears to have slowly edged into isolation and paranoia. But what makes the strip really worthwhile in terms of how it relates to the Locas strips of the here and now can be summed up by one panel: A nude, 40-year-old Maggie, standing with her back to us in all her craggy, doughy, Rubenesque magnificence, looking out the window at Rena, her back also to us, arms akimbo, her 70-plus-year-old back and arms still seeming hewn out of wood despite her age, staring down at gifts left by her devoted fans. But as that mirrored pose indicates, both women have essentially the same plight: To what extent are they comfortable with their achievements? To what extent can they let the people they love into their lives? To what extent are they just standing there alone–or is the important thing that they’re looking at people who care about them? Maggie may just be an apartment manager anymore, she may now get in way over her head (literally) when she attempts to have a fun island adventure like she used to, but the way Rena sneaks into her room at night just to watch her sleep reveals that the aging heroine could use a dose of the community and camaraderie that’s part and parcel of Maggie’s dayjob. A life spent fighting people in the ring and the streets has left her admired but alone; Maggie’s misadventure teaches her it’s okay to focus on the former to ameliorate the latter.

Accompanying the main strip is “Gold Diggers of 1969,” a flashback strip drawn in Jaime’s Sunday-funnies kiddie-comic style and concerning li’l Maggie as she bounces between her three other mother figures–her actual mom, her Tia Vicki, and her babysitter/mentor Izzy from back in her wannabe-gangsta teenage years–on a particularly dramatic day. Again we see the ways in which these strong women are weak (I was particularly tickled by the revelation that Izzy’s not a founding member of the Widows at all; sorry, Speedy), and the ways in which they draw strength by helping to protect people weaker than they. Little Perla’s way too young to really notice any of this, but I think that’s the point–flash forward about 15 years when she’s off gallivanting with Rena in the jungle, and she’s still mostly too besotted with hero worship to notice the toll Rena’s glamourous, dangerous life has taken on her. In much the same way that connecting with her new baby brother and her mom and dad makes young Maggie feel like part of a whole, so too does her semi-disastrous visit to Rena at age 40 help give a hero her strength back. What a kindly pair of comics.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: The Education of Hopey Glass

October 18, 2010The Education of Hopey Glass

(Love and Rockets, Book 24)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2008

144 pages, hardcover

$19.99

The “all growns up” phase for the Locas continues. Looking back, the material collected in Penny Century was sort of the calm before the storm for our heroes and heroines–the point at which they’d matured, but the point before they realized they’d matured and started struggling with it. If Ghost of Hoppers was Maggie’s confrontation with adulthood, The Education of Hopey Glass serves up the equivalent for Hopey and Ray. It’s fascinating to me to see where their lives have taken them versus where they were–and more importantly, what they represented to Maggie–when they were first juxtaposed. For starters, this is a really weird and kind of silly thing to say about a comic book character, but I am straight-up proud of Hopey for becoming a teacher’s assistant. (Waiting for Superman can go pound sand.) It reveals a strength of character she’d always kept carefully hidden, an indication that beneath the hellion exterior, she’s actually, well, a good person, a person capable of caring about someone other than the Maggot. What’s refreshing about what Jaime is showing us here is that this in no way “fixes” Hopey, nor makes her suddenly respectable. She’s still a loudmouth bartender and an incorrigible womanizer with a wandering eye, and she still can’t seem to help but hurt the people who care about her. And on the more positive side, she’s still sexy and funny and badass and all the other things that have made her fun for her friends to be around. Her new job in a position of responsibility isn’t something she sacrificed the person she’d always been to achieve. Like the glasses she spends the storyline shopping for, it’s just a new accessory on the same old face, a new way of looking at things with the same old eyes.

Good ol’ Ray Dominguez, on the other hand, is more ol’ than good at this point. The rumpled, cigarette-smoking noir narration we encountered from him last time around is back with a vengeance, and the succession of endless nights of booze, broads, and loneliness it suggests tells us that much has changed over the nearly two decades since he first emerged as the safer, more caring alternative to Hopey in the quest for Maggie’s heart. This is not to say that he’s the full-fledged devil-may-care degenerate of the sort comprised by the circles his old friend Doyle and his would-be flame Vivian “The Frogmouth” Solis move in–on the contrary, his relentless narration is a litany of worrying that he’s too old, a given situation too hairy, a given woman too much trouble, a given dude too dangerous even to know. And yet through some innate inability to really stick up for himself and go for what he wants, Ray is constantly buffeted from predicament to predicament by the still more fucked-up people with whom he surrounds himself–a classic noir patsy protagonist, played mostly for Lebowski-style black laughs. Ray wonders aloud why he’s so fixated on the two years he spent with Maggie all those years ago, especially in light of what he eventually gets going with Viv, but it feels like less of a secret to us: He saw what he wanted and hung onto it. My fear is that the Frogmouth is too much of a (hilarious!) human disaster area to give him the gumption to do so this time around, but anything’s possible, and he seems to realize that it’s now or never.

What makes these two stories compelling and connects them to one another beyond the basic idea of the characters coming to terms with their age is how much the stories rely on the kinds of things only an artist of Jaime’s caliber can pull off for their telling. Hopey’s many loves and crushes–Maggie, Rosie, Grace, Guy Goforth, Angel, the woman at the eyeglasses store–are woven into an intricate web of eye contact and body language, glances and looks away, the clothes they choose to wear and what they look like naked. Half the story emerges from characters looking at how other characters look at still other characters. Ray’s story, meanwhile, takes place about 30 feet in front of a murder mystery, if you will, one that he and his friends remain half-aware of and half-willfully oblivious to as it approaches, takes place, and ripples out into its aftermath. As Ray does his thing, we’ll see people behind him start arguing and fighting, whisper to one another, disappear and reappear, shoot daggers at one another or look sheepish and sick. Ray putting it all together is one of the catalysts for him trying to get his own act together by the end of the story–and it wouldn’t have been possible if Jaime hadn’t been such a poet of bar fights and parking-lot conspiracies in the rear of the panels. Maybe adulthood isn’t just choosing a new way to see with your same old eyes, but also choosing not to look sometimes, too.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Ghost of Hoppers

October 15, 2010Ghost of Hoppers

(Love and Rockets Book 22)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2006

120 pages, hardcover

$18.95

Jaime Hernandez has long displayed an infrequently utilized but alarming alacrity for horror. The Locas comics’ outbursts of genuine violence have been scary–I’ll never forget Hopey getting stomped on in the bathtub and staggering out, leaning naked against the door frame, or Speedy half-lit by the streetlight, a portrait of a young man at the very moment he hits rock bottom that chills me to my very soul. But in general the real terror, the real exercises in creating and sustaining horror imagery, emanate from Izzy Ruebens. Maggie and Hopey’s long-suffering, eccentric mentor has slowly withered, almost, over the years, from the semi-comical parasol-wielding goth of the strip’s early, punky days to the stoic, emaciated, frequently naked presence we’ve seen in Penny Century and now Ghost of Hoppers. Whether she’s simply mentally ill or genuinely haunted (and the two aren’t mutually exclusive possibilities, to be sure) is almost immaterial. In either case, the danger comes simply from seeing what she sees. The shadows, the stains, the shattered and inverted crucifixes, the black dog, the flies on the ceiling–these are monumental horror-images, frightening not because of some physical threat they present but the violation of reality they represent. They’re frightening by virtue of their very existence. Something is wrong with them. All of the damage they’ve caused–and based on what we know of Izzy’s guilt over her abortions and suicide attempts, the damage that caused them–has been self-inflicted.

At first I struggled with why Jaime would choose this particular storyline–Maggie Realizes She’s All Grown Up, basically–to delve deeper than ever into this aspect of the Locas world. I mean, this thing becomes a horror comic toward the end, easily the most sustained such work in the whole Locas oeuvre. What does any of it have to do with the misadventures of Maggie, the story’s protagonist? But then it clicked: She, too, is threatened here by the violation of her conception of reality. Is she the badass punker she always thought she was, or has she grown up to be a square like everyone else? Is she basically just a fun-loving straight girl with one exception that proves the rule, or might she be physically and emotionally attracted to other women after all? Is she okay with the friends-with-benefits relationship she’s had with Hopey since time immemorial, or does she want something more? Were she and Hopey really the center of the universe, or were there equally vibrant and vital relationships that continued on without them? Can she maintain her self-image as a troublemaker when she’s at a place where she really kind of hates trouble? Does Hoppers–her neighborhood, her hometown, her group of friends and fellow travelers–still exist in her mind as a screwed-up but happy place to visit, or has the passage of time rendered that all a lie? No wonder the black dog chooses now to pay her a visit. She had so much to be frightened of already. Thank goodness that life sometimes grants even hapless Locas an exorcism or two on the house.

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Penny Century

October 13, 2010Penny Century

Love and Rockets Library: Locas, Book Four

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2010

240 pages

$18.99

Grown-ups! More or less. This volume collects stories that follow the conclusion of Love and Rockets Volume One, the initial years-long run of the series’ comic-book format–first in spinoffs and standalones, then in L&R Volume 2–and it’s clear Jaime took the dividing line seriously. From the largely wordless wrestling action of “Whoa, Nellie!” to the less spotted-black-driven line art of the “Maggie & Hopey Color Fun” (here presented in glorious black and white), the comics in Penny Century look less dense and read that way, too. Maggie and Hopey seem to have settled down, somewhat–no longer careening from adventure to adventure or disaster to disaster, still involved in the lives and schemes of their eccentric friends but no longer completely swept up by them, still romantically (or at least sexually) entangled with one another but not to the all-or-nothing extremes of the past. The most frantic strips in the collection, “Chiller!” and “The Race,” are a late-night driving-alone mind-playing-tricks-on-Mag freakout and an out-and-out dream sequence respectively. The horns on H.R. Costigan’s noggin, heretofore the Locas strips’ only remaining visual link with their sci-fi roots, are explained away. The most outlandish thing that happens here, Izzy’s magic-realist transformation into a giant, is tied to her very adult concern about an upcoming reading from her recently published memoir, and the comic’s last remaining great free spirit, Penny Century, spends most of the book hiding from attention and is then widowed. Even the “who’s who” portrait page at the back of the book has been cut. The wild-oats-sowing crises of the sort that drove “Wigwam Bam” and “Chester Square” are over. The Locas have matured.

Ironically, perhaps, Jaime takes this opportunity to indulge himself, if not his characters. He transforms Ray D. into a sort of hard-boiled hard-luck case, whose first-person narration captions speak of falling in with femme fatale Penny and cruising for action like the least violent installment of Sin City ever. He tells his longest li’ Locas story yet in “Home School,” which reveals the origin of Izzy’s undying affection for Maggie in a fashion that’s adorable–and carefully observed–as young Maggie’s plight is revealed to be heartbreaking. He has Penny avoid the impending circus her life is about to become by also avoiding clothing. He draws page after page after glorious, please-study-this,-Avengers-artists page of women’s wrestling action, an absolute master class in conveying the physical consequences of bodies in motion and collision.

And in the collection’s gutsiest, flashiest move, he turns one of his long-running storytelling innovations into ostentation by completely eliding Maggie’s entire marriage until we learn of her divorce. Obviously, the Locas stories are full of events we only find out about after the fact–from Esther’s forced haircut to Ray and Penny’s affair–but usually the characters involved were off-screen at the time. Maggie, on the other hand, remains our main character for the bulk of this book, so finding out she married a dude during that time comes as a shock. It’s kind of gratuitous, even–it’s Jaime doing the Jaime-est thing he could possibly do with his signature character. Why? Why not? That ends up being a sufficient answer. Sure, we go along with it in the end in large part because the flashback history we discover between Maggie and Top Cat Tony is convincing, and because Locas has always been about the past’s bizarre on-again off-again romance with the present. But mostly we go along with it because it’s fun, because Jaime has earned the right to even the most spectacular stylistic flourishes–sort of how Tony’s okay with Maggie’s dalliances with Hopey, since, well, that’s Maggie. Settling down often just means owning your weirdness.

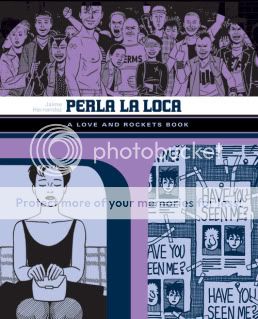

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Perla La Loca

October 11, 2010Perla La Loca

(Love and Rockets Library: Locas, Book Three)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

288 pages

$16.95

Things take a turn for the unpleasant in this volume. I don’t mean sad or heartwrenching–they’ve already done that; I mean unpleasant. Taking a look that old negative review of Locas I wrote, I’m pretty sure this is where Jaime lost me completely the first time around. Ray can’t get it together enough to hang on to Danita, and she skips town. Doyle can’t get it together enough to hang onto himself, and he skips town. Penny’s pretty much settled into the unfulfilling life of being Mrs. H.R. Costigan, theoretically banging out kids with her manservants as a way of passing the time. Maggie brings disaster everywhere she goes (though she means well, at least). And Hopey! With the image of her smoking on the toilet while pregnant still fresh in our minds from the last volume, she she falls in with a bunch of people just as glib and nasty as she is–only as it turns out they’re even worse, and several people are beaten nearly to death for her to learn that lesson. Love and sex were never quite “carefree” in the Locas stories–people pined and got hurt at least as often as they had a great time or did really romantic and loving things–but in this volume the sex gets downright seedy, transactional at best and joylessly fetishistic at worst. It’s a book about creeps.

Fortunately I’m now able to accept that. I don’t know what the hell came over me when I wrote that old review, to be honest. In what world does making art about creeps necessarily constitute and endorsement of being a creep? Upon this re-read it’s quite clear that Jaime is in no way rah-rah’ing Hopey’s behavior, which he consistently depicts as show-offy, designed for audience consumption. I mean, she elbows a crowd of prostitutes out of the way to go down on someone, and out-hipsters everyone by declaring an aging TV star’s pedo-fetish lifestyle: “I think it’s super-cool.” No one must ever accuse Hopey Glass of being in any way square! As we see from flashbacks to her as a squirmy little girl refusing to sit still for a photographer, and as a teenage asshole subjecting her loyal friend Daffy to a humiliating encounter with an S&M whackjob, she thrives on other people’s disapproval. She lives to be a magnificent bastard. Only this time around, the bastardry comes back to bite her.

Maggie is a much nicer person and therefore her story is a lot nicer, but she’s now getting less out of her basket-case love life than ever. Far away from anyone with whom she ever had a good thing going–Hopey, Ray, Casey, even Speedy or Race–she falls into a pattern of breaking the hearts of the people who are interested in her and screwing up the lives of the friends who aren’t. Her chaos has become contagious. And her now-rare moments of sexual intimacy use cash as a buffer. “The real secret is that I really didn’t feel bad about doing it,” she confides, “Like it was no big deal.” What a relief that must be to her, since “everything is a BIG DEAL” is basically her life story!

So what conclusions are we to draw from all this? It’s taken me a while, but I’ve come to the conclusion that drawing a conclusion is the wrong thing to do. There’s not some message being sent here about, I dunno, punk or fluid sexuality or sex work, which are sort of the common threads of the two big stories here–the Hopey-centric “Wigwam Bam” and the Maggie-centric “Chester Square”-to-“Bob Richardson” suite. The message, I think, is simply to be found in the fact that there are two big, separate Maggie and Hopey stories here. They’re not symbols, they’re people. Here you have two people who were once so inseparable and similar that their friends and enemies called them The Incest Twins, and now they’re finally, really living apart. When two people have formed their identities in such an inextricable way–in Maggie’s case it’s so profound that it’s the exception that proves the rule of her sexual orientation itself–what happens when you extricate them? Well, they make some really shitty life choices, they have a hard time figuring out who they are, they hurt some friends, they get some other friends hurt, they make still other friends wonder if they were really such great friends to begin with, they hurt themselves, and they start–barely–to move on. All in the hands of the kind of artist who can draw characters to have family resemblances or to look enough alike that other characters can’t tell them apart, but we the readers can even while seeing those resemblances. Story made possible by sheer chops. Damn.

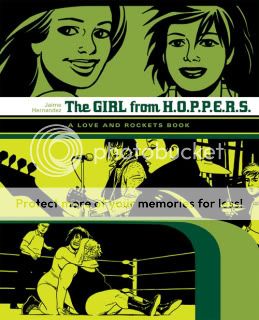

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S.

October 8, 2010The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S.

(Love and Rockets Library: Locas, Book Two)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

272 pages

$14.95

Do you ever stop to think that David Lynch’s work doesn’t make sense? No, not in that way–I don’t mean in terms of story logic, I mean in terms of his aesthetic/generic approach. In that case, your answer is probably “No, I haven’t.” But seriously: Pre-Beatles rock and roll nostalgia, soap-operatic melodrama, supernatural beings, naked ladies, small towns, Los Angeles, non-linear narratives, hideous violence, Angelo Badalamenti…there’s really no reason why all of that should get lumped together, or why all of it should work together, but somehow it does and so you almost never pay attention to what a hodgepodge it is. Something about what Lynch does, the confidence with which he does it, makes it feel seamless, like “of course” rather than “what the?”.

Looking at the cover for The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S., I realized the same is true of Jaime Hernandez’s comics. There isn’t any particular reason for a sprawling slice-of-life saga to concern itself with punk rock, Mexican-American teenagers and twentysomethings, a pair of on-again off-again girlfriends/best friends, barrio life, and professional women wrestlers, with a soupcon of comic-book sci-fi thrown in now and then–no reason beyond that’s what Jaime was interested in making comics about. But you read a story about Hopey ditching Maggie to tour with the shitty punk band she’s in with her ex-girlfriend, and Maggie getting over that and the murder of the dude she’d been into for years/her Goth friend’s cholo kid brother by becoming the sidekick for her aunt/the women’s heavyweight champion, without batting an eyelash. That’s what a Jaime comic is, the same as a David Lynch movie is doppelgangers, broad comedy, hot sex scenes, early ’60s pop classics, a cameo by some impossibly cool rock star, and someone getting their brains blown out. He created his own kind of story.

So that’s thing #1 that struck me about this collection, wherein the sci-fi stuff is largely dropped once you get past the opening section (and is outright rejected in a cheeky self-parodying strip that ends with present-day Maggie tossing aside a “Maggie the Mechanic” comic book with a “yeah, right”) and wherein the Locas material goes from being a really good comic to a really great comic. Thing #2 is that Tom Spurgeon is right to list “memory” as one of Jaime’s hallmarks, above and beyond “spotting blacks” or “portraying rock and roll in a way that actually captures what’s awesome about it” or “drawing cute girls in bathing suits.” I think it’s the introduction of extensive flashbacks that makes this material so strong, so fascinating, and so epic in scope. For starters, it’s fantastic in a fannish way to learn the “origin stories” of Maggie & Hopey (“The Secrets of Life and Death Vol. 5,” “The Return of Ray D.”), Hopey & Terry (“Tear It Up, Terry Downe”), and Izzy (“Flies on the Ceiling”). A student of superhero comics like Jaime was obviously gonna cotton to the appeal of that sort of thing.

And of course, flashbacks serve to flesh out Jaime’s ever-expanding cast of characters. In that interview I ran the other day, Jaime mentions how he’d pick out characters he’d drawn in the background and use them whenever one of his main characters needed a new boyfriend, say–fleshing out the Locas world with stuff that’s already present. Flashbacks do the same on a narrative level: You don’t need some big character-revealing adventure with new character Doyle, say, with all the implications that might have for where you want to push the present-day story of everyone he interacts with, when instead you can rewind a few years to “Spring 1982” to see what he was like then. The contrast that arises between the genial slacker we met earlier in the volume, with his tousled hair, stubbly chin, drooping cigarette and shit-eating grin, and the scowling ex-con and ex-addict so scared of his potential to do wrong that he literally flees town we see in this flashback story says more than enough about the potential for characters in the Locas-verse to grow and change.

But from a formal perspective, this is where Jaime really starts playing with gaps on comics’ atomic level, that of panel to panel transitions. There’s this one great, totally unnecessary bit where Maggie’s fearsome aunt Vicki’s wrestler boyfriend comes to Maggie to divulge that Vicki really does care about how Maggie feels about her, but rather than stick that in a word balloon or three, Jaime jumps from a panel on the left in which the guy says “Wait, kid. Listen to me a second…” to a panel on the right where Maggie, already storming away, says “She said that, huh? So what am I supposed to do, feel sorry for her when she breaks my arm?” You’re not jumping from place to place or era to era here, you’re not doing anything that might occasion a jump cut in a more traditionally executed comic–you’re just skipping a non-essential part of a conversation, without missing a beat. Time is porous in Jaime’s hands, prone to dropping out from under you or skipping back and forth within a single page, let alone from story to story. The rise to prominence of flashback stories reflects that on an “as above, so below” level.

Most importantly, though, I think, is that this collection is where death becomes a presence and a factor in the characters’ lives. Not the impersonal, absurdist, satirical deaths caused by the depredations of Maggie the Mechanics mad sci-fi robber barons (and wasn’t it funny that the science fiction adventures Maggie had were the opposite of escapist–she was constantly hoping to escape from them?), but the death of family members and friends and babies, murder and the threat of murder, criminality and insanity. It’s the volume where you learn how Speedy, really without even thinking about it, has hurt too many people over the years too badly for them to stay close to him when he needs them the most; how Izzy is so haunted by guilt that, regardless of how literally you want to take what we’re shown here, it’s become a relentless, inescapable presence in her life, quite literally destroying her personality. Awareness of death, of our mortality, is part of what makes us distinctively human; I think the ability to remember is just as integral to us. Certainly that’s the argument Jaime makes when he ends “The Death of Speedy Ortiz” with a one-page flashback to a wedding reception of no particular importance. Memory is how we fill in the gaps death leaves behind.

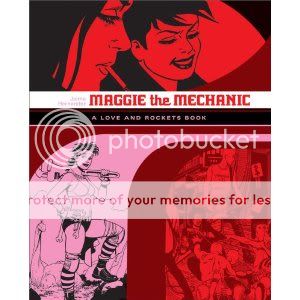

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: Maggie the Mechanic

October 6, 2010Maggie the Mechanic

(Love and Rockets Libary: Locas, Book One)

Jaime Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

272 pages

$14.95

If it weren’t for Jacob Covey and Bryan Lee O’Malley, I don’t think you’d be reading this post. Aside from Jaime Hernandez himself, they’re the two men most responsible for persuading me to pick up the digest editions of Love and Rockets that Fantagraphics began releasing a few years back, and for how hard those digests clicked with me when I did. Covey’s attractive design of the digests made the most of the power of Jaime’s art, individual panels of which work as stand-alone images as strongly as those of any cartoonist ever to put pen to paper. (I recognized that even as a Jaime skeptic.) Combine that with bright colors and the digest format itself–chunky enough to feel substantial, light enough to fit in a backpack and be read comfortably on the train or the beach, tailor-made to be lined up on a bookshelf–and you’ve got a series of books that are compulsively collectable and readable. O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim series served a prophetic role in this regard: A format that’s similar (though not identical) and similarly delectable; crisp, stylish black-and-white art incorporating a variety of traditions and influences into the basic alternative-comics tradition; a fast and loose approach to genre fiction that uses it as a spice rather than the main ingredient; compelling portraits of an incestuous social circle of music-interested, kind of feckless young people with disastrous love lives…reading Scott Pilgrim primed me for revisiting Jaime’s “Locas” material, ready to accept it for what it is (“Locas”!) rather than what it isn’t (“Palomar”). No, I could never go back and recreate the experiences of the long-time die-hards who grew up with Maggie and Hopey in every individual issue; but barring that, I’d found the ideal combination of content and format. Putting it all in fun little digests rather than a big portentous hardcover somehow made it all click.

And so, instead of being put off by Maggie’s borderline-bipolar hysterics, Hopey’s surliness and occasional cruelty, and Penny’s bombshell ridiculousness…well, that’s who they are, isn’t it? I feel like it’s somehow an insult to the whole critical project if I say “I used to find them all pretty annoying, but then I learned to accept it and move on”–like, c’mon, was it really that simple? And the answer is yes! Instead of bashing my head against the fact that they weren’t more together, or that they weren’t falling apart in the way my personally preferred alternative-comics protagonists tend to fall apart, I suddenly found myself digging it. For example, it’s funny and endearing watching Maggie fall all over herself around the alpha males she’s attracted to, and to contrast this with the alpha females with whom she surrounds herself as friends. Izzy Ruebens, Penny Century, and Hopey Glass are all a bit whacked-out in their own ways, but the personas they’ve constructed for themselves as a way of dealing with their problems are rock-solid, even overwhelming to newcomers. Maggie Chascarillo, by contrast, is an open book–even her attempts to cloak her true feelings send an equally true message in block letters five feet tall. Her inability to repress herself is her charm, and it’s reflected by the physical business Jaime is constantly involving her in–crashing hoverbikes, breaking machinery, ripping her pants, getting tossed around by wrestlers and thugs and explosions. She’s sort of an explosion herself!

(On a related note, I almost threw Terry Downe on my list of the alpha-Locas, but I can’t get around that one heartbreaking panel in this collection where her glacial hardass facade crumbles and she begs Hopey to tell her what Maggie has that she doesn’t. Hopey’s hold over Terry is that she brings out the Maggie in her.)

Making his protagonist a basketcase (albeit a sexy one–let’s be honest, that’s a big part of the appeal of this material too) is just one part of what impresses me so much any time I revisit this material: I’m struck by just how confident it is in itself. What I really mean by that, of course, is LOOK AT THIS FUCKING COMIC. Can you imagine what the reaction would be if a cartoonist today came out with a debut with the chops Jaime’s displaying in the very first issue? Keep in mind I’m not just talking about the crosshatchy prosolar-mechanic sci-fi stuff: The second story is “How to Kill a…,” a wordless, increasingly abstracted portrait of Izzy as a young writer, hinting not only at the formal mastery Jaime would later display (it’s all jumpcuts and comics-as-design), but at the psychological (and supernatural!) depths Izzy’s gothy exterior would be revealed to contain years later.

And on a narrative level, Jaime spends no time at all explaining his world, why it bounces back and forth between a realistic portrait of young poor Latina punks and a light-hearted science-fiction satire of Reagan-era Latin-American political upheavals. Like magic realism gone Marvel Comics, it just throws you right into the deep end and expects you to swim. This is true even if you’re just talking about the realistic stuff, the person-to-person relationships, and it’s established right in the fourth panel, where Maggie complains about having had too much to drink last night: These comics predicate themselves on things that already happened. Nearly any time a new character is introduced, they’re after money someone owes them, or getting teased for the crush they’ve been nurturing on another character for years. It’s an in medias res world.

Okay, so a lot of it will be filled in with flashbacks eventually. We get a glimpse of this in “A Date with Hopey,” the story that concludes this volume and is its strongest single strip. Our hapless hero Henry’s one and only appearance relates how his sporadic, intense friendship with Hopey evolved into unrequited love, ended in rejection, and now exists as a bittersweet memory; the laserlike precision with which the story pinpoints powerful emotions nearly everyone has experienced serves as a model for the future of the Locas stories. (And, contra what I used to think, it’s proof positive that Jaime is fully aware of the damage Hopey can carelessly inflict, even as its her carelessness itself that makes her so irresistible.) But the way you’re just dropped into Maggie & Hopey, Already In Progress, is pretty much why I continue to recommend this volume, rather than its relatively sci-fi-free successors, as the place to start if you’re interested in Jaime’s work. I understand why that doesn’t work for everyone–and it’s true, the earliest comics are relatively talky and old-fashioned-looking as befits their influences. But if you start late in the game, you’re not just missing dinosaurs and rocketships and robots and superheroes and such–you’re missing what really feels like a couple years in the life. Even by page one, we’ve already missed so much!

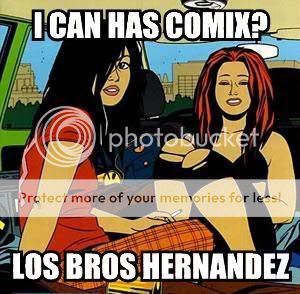

LOVE AND ROCKTOBER | Comics Time: An interview with Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez

October 4, 2010NOTE: Back when I worked for Wizard magazine’s website, WizardUniverse.com, I conducted a series of interviews with alternative-comics creators titled I CAN HAS COMIX? That title was a little problematic with some folks at the company — as were the transcription bills — but whaddayagonnado. I kicked the feature off on June 22, 2007 by speaking with Los Bros Hernandez, and I’m reposting the interview here because I think it’s a pretty solid introduction to/overview of the brothers, Love and Rockets, and what I get out of it all.

I CAN HAS COMIX?: GILBERT AND JAIME HERNANDEZ

In Wizard Universe’s new alternative comics interview column, Los Bros Hernandez reveal how their shared love of punk rock, sexy girls and Silver Age classics helped their epic series Love and Rockets launch the indie scene as we know it

By Sean T. Collins

I’ll admit that it took me a while to hitch a ride aboard Love and Rockets.

Despite the near-universal acclaim the series and its creators have received over the 25 years since the series’ first issue took the comics world by storm and kick-started a small-press revolution–the fruits of which can be seen at this weekend’s MoCCA Art Festival in New York City–there’s something daunting about it. For starters, it’s not just a straightforward one-man show: It’s an umbrella title for the work of Los Angeles-born brothers named Gilbert and Jaime (and sometimes even older sibling Mario), collectively known as “Los Bros Hernandez.”

What’s more, both Gilbert and Jaime have developed their own mini-mythoi within L&R, featuring enough characters to rival your average superhero universe. In Gilbert’s case, you have the busty, hammer-wielding femme fatale Luba and her friends, lovers, family and enemies, all swirling around the fictional Latin-American town that gives Gilbert’s “Palomar” saga its name. Jaime’s stories center on unlucky-in-love mechanic Maggie and her obnoxious punk-rock best friend/sidekick/sometimes-lover Hopey, wild women who are the stand-out members of a loose-knit group of L.A. ladies dubbed “Locas.” Both casts of characters age in real time, meaning some people who started the series as teenagers now have teenagers of their own, with their own adventures. The warts-and-all presentation of the series’ leads (particularly Jaime’s, in my case) can leave you as pissed of as you’d be at your own obnoxious friends.

And to top it all off, Love and Rockets has spawned two separate ongoing series using that title, a raft of trade paperback collections, two massive hardcovers housing nearly the entire “Locas” and “Palomar” sagas, and countless spinoff miniseries, graphic novels and even adult comix. Put it all together and it’s enough to make the friggin’ Legion of Super-Heroes’ continuity seem easy to follow.

Until now.

To celebrate L&R‘s 25th anniversary, publisher Fantagraphics recently began releasing awesomely affordable, handily portable softcover digest collections, starting at the beginning of both brothers’ epic storylines and giving readers their best chance ever to get in on the ground floor. With the first volumes (Jaime’s Maggie the Mechanic and Gilbert’s Heartbreak Soup) already in stores, the second installments–The Girl from H.O.P.P.E.R.S. by Jaime and Human Diastrophism by Gilbert–launched this week, with some of Los Bros’ best work ever on board.

I could go on about both brothers’ mastery of character development, creating people as flawed, funny, and fascinating as your best friends. I could wax rhapsodic about their sophisticated storytelling, which relies on the readers’ intelligence as it bounces back in forth in time and between dozens of characters. I could point out that at different times, it’s the funniest, raunchiest and scariest comic you’ll ever read. I could talk for ages about the gorgeous art–Jaime’s sharp, sexy, stylish classicism and Gilbert’s earthy, equally sexy surrealism. And I could say that while you hear a lot about “creating a universe” in comics, no one’s ever done it better than Los Bros–when you read an L&R story, you feel like you’re catching just a small glimpse of a world as big, sprawling, messy, funny, horny, heartbreaking and real as our own.

Instead, in this joint interview with Gilbert and Jaime, I’ll let Los Bros themselves explain the inspiration of the series, reveal the dark secrets of the stories in the new digests, and announce their pick for the greatest superhero comic of all time. Through it all, it’s clear that when it comes to creating thrilling uncategorizable comics in Love and Rockets, the brothers are still armed and dangerous.

WIZARD: Take us back to 1981 when you guys started the books. What made you say, “Let’s do this”?

JAIME: Let’s see, 1981…I was being paid to go to junior college, so I didn’t want a job. I was just taking art classes and stuff like that. I wasn’t thinking about what I was going to do with my life–I just liked drawing comics. By that time we were drawing comics for ourselves, but we were starting to draw them with ink on the right paper and everything, not just on a piece of typing paper with a pencil. We wanted to print it somewhere but we didn’t know where, because it wasn’t your normal Marvel or DC fare. There wasn’t really much of a market for this stuff, we thought. We were still punk rockers in bands and we were just doing comics. We wanted to draw comics the way we wanted to see them, and we weren’t really seeing much of them out there.

GILBERT: Comics were our amusement for years, and what we were into was not what the mainstream companies were into at the time. We figured that by printing an underground magazine we would get it out there, mostly to see what the response would be–just something to do, really. It turned out that when we finally got our stuff together and put out a 32-page Love and Rockets comic, a fanzine/underground type thing, we were luckily noticed right away by Fantagraphics. The timing was just right–they were ready to publish their own comics. It took a little climb to get Love and Rockets going, but the response was very good, even in a small way at first, so that encouraged us to continue.

It’s not too often that people in the alternative comics area have that kind of success right out of the gate, but I guess you guys didn’t have a lot to compare it to. Before Love and Rockets there were the undergrounds, but they were sort of a different beast.

GILBERT: Yeah. Cerebus and ElfQuest were actually encouraging in the sense that it could be done, getting a following for a black-and-white comic. It wasn’t necessarily mainstream. Even though they were both geared for that audience, they were successful on their own.

Jaime, you had more “mainstream” elements in your early work, with its sci-fi flavor. Was that an attempt to tap the normal comics-reading audience, or was it just you following your bliss?

JAIME: It was pretty much just me. I liked drawing rockets and robots, as well as girls. [Laughs] It really was no big game plan. It was almost like, “Okay, I’ll give you rockets and robots, but I’ll show you how it’s done. I’m gonna do it, and this is how it’s supposed to be done!” I went in with that kind of attitude.

That’s definitely a punk attitude.

JAIME: Yeah. I’d see something was being done in other comics and I’d say, “Ah, no, no, that is not the way to do it. This is the way to do it.” That gave me encouragement to just do it. In the beginning, I was putting my whole life of drawing comics since I was a kid into this comic. When the characters started to take over, the other stuff started to drop out because it was getting in the way.

And the result was a book that’s been credited with inventing alternative comics as we know them, though that couldn’t have been your intention at the time.