Posts Tagged ‘brad wesley’

181. Memphis

June 30, 2019“Dalton,” Brad Wesley says. “I have a cousin in Memphis. Tells me you killed a man down there. Tells me you said it was self defense at the trial. But you and I know that isn’t so, don’t we.” Even in a scene as cockamamie as the Breakfast Conference, this series of statements makes an impact.

First and foremost it confirms what to this point had only been treated as part of Dalton’s cooler legendarium—a potential tall tale about ripping a man’s throat out with his bare hands that Hank relates to Horny Steve, and that Horny Steve rejects as bullshit out of hand. Wesley doesn’t mention the unusual method of dispatch at all, as the details do not concern him. What does concern him is that, in his own estimation anyway, he is up against a) a killer, and b) a liar. The former tells him Dalton can be useful; the latter tells him Dalton may be willing to be used.

Second, it shows us that despite all his sangfroid, Dalton does indeed have nerves that can be hit and buttons that can be pushed. He neither confirms nor denies Wesley’s cousin’s report, and a closeup reveals his reaction as muted. It’s only when Wesley claims that the self-defense justification was bullshit that Dalton gets up from his chair, preparing to storm off. Wesley preceded this story by arguing that of course Dalton loves beating people up for cash, that this is both his nature and human nature in general. Telling Dalton this story about his own life, then intimating that they can both sense the truth lurking under the surface, is Wesley’s attempt at turning him into a co-conspirator on this point. Wesley sees a useful man, he concludes that this man may consent to being used, he attempts to paint him into a corner in which he’s being used already, in which his use is a fait accompli. It’s rather deftly done, and that it leaves us not fully sure to what part of Wesley’s version of events Dalton objects is deft as well.

Third, it’s a pleasure to listen to, bearing many of the hallmarks of Road House‘s finest line readings. Ben Gazzara’s voice is a rollercoaster of subtle modulation, a miniature Bleeder Speech. “Dalton” is delivered in his best we are reasonable men, you and I; come, let us reason together voice. “I have a cousin in Memphis” is flatly factual. “Tells me you killed a man down there” swoops upward in register, as if he’s relating an interesting factoid from a wikipedia page he’s reading as he and Denise sit next to each other on the couch after dinner looking at their phones. “Tells me you said it was self defense at the trial” has a conclusory feel to it: Ah, well, that settles that. Then the verbal killshot: “But you and I know that isn’t so, don’t we.” His voice shifts to a level lower than in conclusion, revealing the deeper truth. Despite the sentence construction, this is, in that go-to maneuver of Road House rhetoric, not a question but a statement. They know. They both know.

Fourth…Brad Wesley has a cousin in Memphis.

It’s not the first time Wesley has alluded to family even within this scene; there’s his asshole grandfather, his only sister, and of course his only sister’s son Pat McGurn. (Not to mention his bastard son Jimmy, and no I will not be providing documentation.) So there’s precedent here—just not, more broadly speaking, within the world of action-movie archvillains. I don’t recall any other cousin relationships factoring into the mental landscapes of the big bads of ’80s and ’90s murder-spectacle movies, so this is something of an anomaly.

But how much does this cousin factor into that landscape? Let us first assume the cousin actually exists and is not simply a convenience concocted by Wesley to preserve the integrity of his intelligence network. Do they speak regularly? Does Brad give him or her (pronouns are dropped here, perhaps strategically) the occasional call just to say hello, or vice versa?

If so, how did Dalton come up? Did Wesley happen to mention the name of the new bouncer in town? Was the plight of their mutual relation Pat McGurn the topic at hand?

Or was it brought up deliberately? Did Wesley know some of Dalton’s past haunts, perhaps via the barfolk network into which his goons Morgan and Pat had been plugged for years? Did the cousin hear that a local figure of ill repute had traveled to good ol’ Brad’s stomping grounds?

And who is the cousin? Is it simply some unnamed, offscreen figure, concocted by the writers as a device for relaying this crucial bit of backstory? Or is it someone we’ve met? Someone who figures briefly into the film before this conversation and then returns whence he came to hear Beale Street talk? Someone we witness in Wesley’s company—at his pool party, in his driveway during a postmortem confab about the failed mission to secure reemployment for Brad’s nephew and his own first cousin once removed Pat McGurn, at a subsequent intra-family mission to intimidate Brad’s ex-uncle-in-law Red Webster—who then relays this information offscreen, says goodbye, and then is never seen again?

180. Three Imaginary Boys

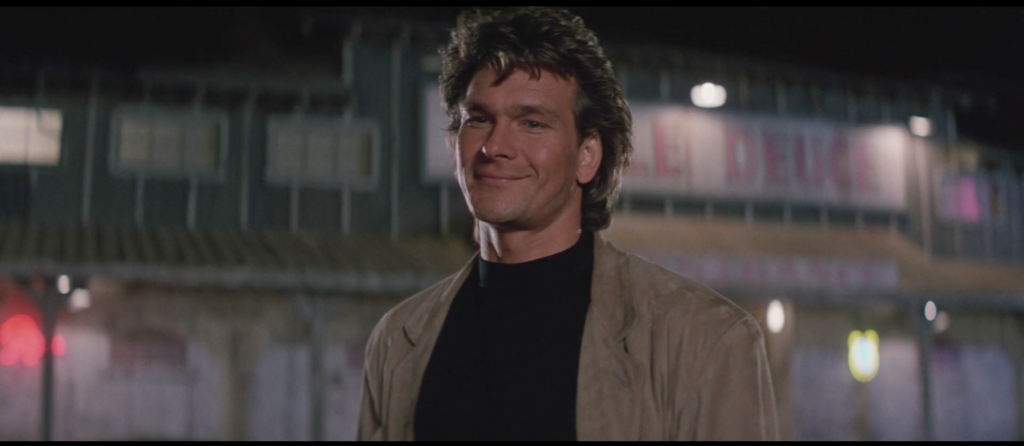

June 29, 2019Brad Wesley is not the only character in Road House in whose eyes Dalton is but a boy. Three others label him as such, and they could not be more different in tone and intent.

First up is Red Webster, one of the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri. An avuncular presence in the film—literally: He is Dr. Elizabeth Clay’s uncle—he asks if Dalton is “the boy from the Double Deuce” when our hero shows up at his store before it opens to have various parts of his car replaced. Just a friendly, getting-to-know-you inquiry, from a guy calling another guy “boy” because he’s younger and he’s just arrived in town. Here, “boy” connotes “newcomer,” someone who is experiencing the world around him with fresh eyes, and who finds himself welcomed by those around him. Excepting the clientele of the Double Deuce as currently constituted, of course.

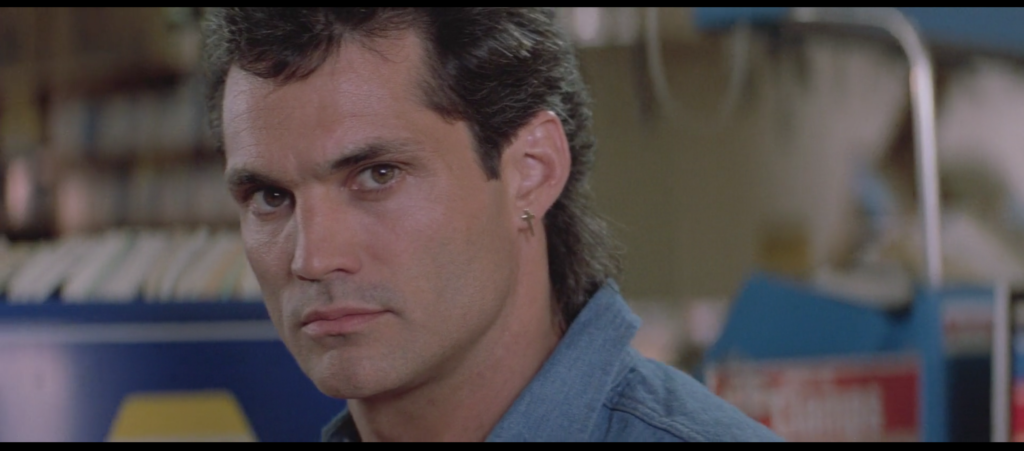

Next is Jimmy, Brad Wesely’s right hand and bastard son [source for this claim?]. “Your ass is mine, boy,” he growls, gesticulating for emphasis in case the owner of the ass of which he is claiming emphasis was unclear. Wesley has just stopped Jimmy from taking on a roughed-up Wade Garrett and a fresh-to-the-fight Dalton 2-to-1 in the Double Deuce, the night Wesley’s men blow up Red Webster’s store and Denise does an aggressive striptease to further assert Wesley’s dominance or something. Here, “boy” means a man less experienced, less tough, less dangerous, less of a man; Jimmy will use the term again when he sneers at Dalton’s fighting prowess during their eventual mano a mano showdown. (His father, spiritually anyway if not biologically, Brad Wesley will pick up the ass-owning baton and run with it, by the way, but not before Jimmy returns to that well implicitly when describing what he used to do to guys like Dalton in prison.)

The third and final boy-sayer is Wade Garrett. Staggering into the Double Deuce the night after Dalton kills Jimmy, Wade has been badly wounded in a fight with three unspecified Wesleyan goons. Dalton realizes that if Wade is still alive, it could be that the hammer is slated to fall on Elizabeth. He rushes out to find her, but not before assuring Wade that he will grant his mentor’s wish at last: They will leave this town and never look back, allowing Wesley to win rather than keep up a fight that by rights isn’t theirs. Wade looks up at the younger man and smiles. “Attaboy, mijo,” he says. Mijo, of course, means “son”; this is the “boy” of approval, of pride, of love. This is the “boy” of a dying parent’s love for his only child.

179. Smart boy

June 28, 2019At the time of Road House‘s filming Patrick Swayze was 36 years old, Ben Gazzara 58. Assuming their characters are the same age that makes Brad Wesley technically old enough to be the younger man’s father, though he’d really have had to make the most of his downtime in Korea to pull it off. Still, 36 is barely a boy’s age in hobbit years, let alone human ones.

Yet “boy” is the diminutive Wesley chooses to employ when favorably comparing the stalwart cooler to his own asshole grandfather: “But you—you’re a smart boy, aren’t you, Dalton? You’re just not too realistic.” He’s intelligent, but a child. He’s not an asshole like Grandpa Wesley, but he’s not a great man like Brad Wesley either. It’s backhanded compliments all the way down.

Or is it? Wesley repeatedly calls his beloved goons his “boys.” And sure enough, before this conversation is through he offers to hire Dalton to bounce on his behalf. It’s an invitation/initiation into the Lost Boys of Jasper that Dalton leaves on the table, but still. Brad Wesley is the only adult in the room, which makes everyone else children in his eyes. He is also the father of Jasper, Missouri, making everyone else his children in his eyes. His destiny, he says, tells him to gather unto him what is his. Are we all that far afield from Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me? For theirs is the kingdom of Jasper.

177. “You ask anybody, they’ll tell you!”

June 26, 2019“Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me!” gets all the attention, and for good reason. In Road House, the archvillain, a man who employs a small army of hired thugs to blow up buildings with recalcitrant old men in them, touts the arrival of The One-Day Sale—Storewide! as his greatest accomplishment. As my own summary goes, “Road House is the story of one bouncer’s quest to free a small town from the iron fist of the guy who is on the verge of opening the area’s first JC Penney. Over half a dozen men will die for this.” So I get it.

I prefer Casino to GoodFellas. Which is not to say I fail to recognize GoodFellas as Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece of mass entertainment, which I intend as a pure compliment. It’s the movie, not the kind of movie but the movie, that makes people fall in love with cinema. It’s like if the philosopher’s stone was rock candy. It’s a towering achievement. But I prefer Casino to GoodFellas because its interests are closer to my own. It’s grandiose, spectacular, it has a machine logic behind its narrative flow, it has pitiable characters and funny characters but no likeable characters, it’s brutally soul-crushingly violent, the music is maybe even cooler than the music in GoodFellas, it reads as a rejoinder to anyone who thought GoodFellas is about how much fun it is to be in the mafia, which may well have included Scorsese himself. It’s not the colossus GoodFellas is, but it stands taller in my heart.

I’m not sure if I’d go that far in describing the line that follows the JC Penney thing, which is “Ask anybody, they’ll tell you!” because let’s be honest, “Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me” is the sound of my soul. But do not, do not sleep on that follow-up. Travel inside Brad Wesley’s mind and look out through his eyes at the town of Jasper, Missouri, and what will you see? A bustling hive of simple little people, buzzing with excited gratitude for what Brad Wesley has done for them, awed by its magnitude, eager to spread the good news. Brad Wesley envisions Dalton driving down the main drag, stopping in one of the town’s countless hole-in-the-wall bars and greasy spoons (Jasper is where Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives manifests Guy Fieri’s id as a tulpa), sidling up to one of the Four Car Salesmen, stopping people at the doors of the Double Deuce, grabbing any man jack off the street, chatting up any swinging dick he sees and getting the same response: “Oh, the JC Penney? It were Brad Wesley what done it.” Like Boromir or Samwise Gamgee contemplating a world in which the Ring gives them Command, Brad Wesley envisions the masses roiling with department-store ecstasy from sea to shining sea, his name rolling off their tongues like glossolalia. Children by the million sing for Brad Wesley bringing JC Penney to Jasper when he comes round. I’m in love. What’s that store? I’m in love with that store.

176. Human

June 25, 2019“Oh Christ,” says Brad Wesley to Dalton, “you get paid for beating people up! Tell me you don’t love it. Of course you do! You wouldn’t be human if you didn’t!” It’s a revealing moment for two reasons. First, it’s the third time in this scene alone that Wesley has employed his favorite blasphemous expletive. I’m going to assume that “Ben, you said ‘Christ’ three times that take, do you think we can go again” was not going to cut any ice on that particular set, so there’s that, but recall which character spreads a gospel with a wound in his side. Second, Brad Wesley’s defining characteristic of humanity is the enjoyment of establishing dominance by inflicting pain, particularly in exchange for cash. This squares with everything we know about him: hiring goons to strong-arm the other weird old men who own businesses around town, beating his girlfriend, citing his survival of “Korea” and “the streets of Chicago” as the sole points of interest in his pre-Jasper biography, festooning his home with the stuffed corpses of literally dozens of different slain animals. (Trust me, you haven’t seen the half of it.) If Dalton needed any more evidence that this is a man who cannot be negotiated with, he has it now. But third, when you turn it around in your mind, you can see it as proof that he does care about his “boys,” the goons. If getting paid to beat people up is a way to do what you love and love what you do, if it proves your essential humanity, then what a gift he has bestowed upon Jimmy, Ketchum, Karpis, O’Connor, Tinker, Morgan, Mountain, and his sister-son Pat McGurn, all of whom he pays to beat people up. For Brad so loved the goons, that he gave his only begotten cash, that whosoever worketh for him should not perish, but have everlasting life.

175. “You bet your ass I have”

June 24, 2019 About the only time I find Brad Wesley appealing as a person, not just entertaining but “ha, this guy’s alright,” is when he laughs and admits he’s robbing the town of Jasper blind. By now you know his litany of achievement: In the name of the 7-Eleven, the Fotomat, and the JC Penney, Amen. After he runs through the catechism, Dalton observes that he’s gotten rich off the locals, intending it to be a charge of parasitism delivered as a balls-and-strikes observation. Wesley doesn’t give half a shit how Dalton intended it, since it’s true, and he can afford to admit it. He grins and chuckles and says in Ben Gazzara’s bullfrog rumble “You bet your ass I have.” He goes on from there, announcing he’s going to get richer, that acquisitive wealth is his destiny, that he’s gathering unto him—he says “gather unto me” in so many words, amazingly—what is his. But that’s the whip cream and the sprinkles and the hot fudge and the maraschino cherry on top. The real banana split of the thing here is straight-up laughing at a guy’s attempt to own him for making money by taking it from other people and going “yeah, and?” You don’t need to admire what he’s doing to appreciate the well-deserved self-confidence with which he’s doing it. I hear Dalton’s braggadocio when he talks to his assembled bouncers about how it’s his way or the high way, with none of the “well gee I suspect it’s always been that way, when a feller earns hisself a degree from NYU and needs to make a livin'” faux humility he serves up elsewhere. I hear my talented and brilliant friends when they’re like “Fuck off, I’m talented and brilliant and deserve to be recognized as such,” one of my favorite things that any of my talented and brilliant friends ever do. They are, and they do, and others should indeed fuck off. Unfortunately for all concerned Brad Wesley isn’t a TV critic or a cartoonist, he’s a gangster who’s willing to lie, steal, and even kill if it means Jasper gets a Sam Goody. But in this way, and possibly only this way, I like the cut of the man’s jib. Alright, this way and the way in which he swerves all over the road while singing “Sh-Boom.” Those two ways.

About the only time I find Brad Wesley appealing as a person, not just entertaining but “ha, this guy’s alright,” is when he laughs and admits he’s robbing the town of Jasper blind. By now you know his litany of achievement: In the name of the 7-Eleven, the Fotomat, and the JC Penney, Amen. After he runs through the catechism, Dalton observes that he’s gotten rich off the locals, intending it to be a charge of parasitism delivered as a balls-and-strikes observation. Wesley doesn’t give half a shit how Dalton intended it, since it’s true, and he can afford to admit it. He grins and chuckles and says in Ben Gazzara’s bullfrog rumble “You bet your ass I have.” He goes on from there, announcing he’s going to get richer, that acquisitive wealth is his destiny, that he’s gathering unto him—he says “gather unto me” in so many words, amazingly—what is his. But that’s the whip cream and the sprinkles and the hot fudge and the maraschino cherry on top. The real banana split of the thing here is straight-up laughing at a guy’s attempt to own him for making money by taking it from other people and going “yeah, and?” You don’t need to admire what he’s doing to appreciate the well-deserved self-confidence with which he’s doing it. I hear Dalton’s braggadocio when he talks to his assembled bouncers about how it’s his way or the high way, with none of the “well gee I suspect it’s always been that way, when a feller earns hisself a degree from NYU and needs to make a livin'” faux humility he serves up elsewhere. I hear my talented and brilliant friends when they’re like “Fuck off, I’m talented and brilliant and deserve to be recognized as such,” one of my favorite things that any of my talented and brilliant friends ever do. They are, and they do, and others should indeed fuck off. Unfortunately for all concerned Brad Wesley isn’t a TV critic or a cartoonist, he’s a gangster who’s willing to lie, steal, and even kill if it means Jasper gets a Sam Goody. But in this way, and possibly only this way, I like the cut of the man’s jib. Alright, this way and the way in which he swerves all over the road while singing “Sh-Boom.” Those two ways.

174. Ozymandias

June 23, 2019

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

‘I brought the mall here, I got the 7-Eleven, I got the Fotomat here;

Christ, JC Penney is coming here because of me! You ask anybody, they’ll tell you!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

172. Lebowski (III): Korea

June 21, 2019Brad Wesley may bear a closer to resemblance to a very different captain of a very different industry from The Big Lewbowski, but in recasting the Korean War as a crucible for personal growth rather than the grotesque slaughter of a country by warring empires he has more in common with Jeffrey Lebowski than with Jackie Treehorn. (As far as we know, anyway; it’s entirely possible Jackie Treehorn froze his dick off in early 1951, leading to his belief that the brain is the biggest erogenous zone.)

When Wesley came to Jasper after Korea, he tells Dalton, there was nothing. His ambition stems, then, from a kind of horror vacui; this would account for his work in the area as a developer, entrepreneur, and establisher of the area’s first Slurpee machine, and it may stem from his experience with privation during that grim time overseas. For the Big Lebowski, Korea afforded him the chance to tell a non-sob-story sob story, about how a gentleman from the People’s Republic cost him his legs, but excuse me sir, spare me the pity and hold back the handouts, everything he’s done since is a testament to his indomitable will to achieve, legs or no.

In both cases the Korean Character-Building Exercise did precisely nothing to make either of these men worth more than a pisshole in a snowbank. Lebowski married into money, and his avant-garde artist daughter Maude allows him the fig leaf of a charitable foundation and a trophy wife to keep him from blowing her late mother’s fortune. Wesley built a mall and some strip-mall stores and hires semi-competent legbreakers to bust up auto-repair shops and dive bars to keep the locals in line. Both men wind up lying on the floor of their own palatial homes in humiliation and defeat by the end of their respective films, though Lebowski at least is still a going concern afterwards, which is more than we can say for Jasper’s JC Penney baron. The paths of glory lead but to Frank Tilghman’s shotgun and Walter Sobchak’s misdiagnosis of paraplegia.

170. Grandpa Wesley

June 19, 2019At least I assume it’s Grandpa Wesley; it’s hard to imagine Brad Wesley celebrating his matrilineal anything, even his kindly Pep-Pep. What’s for certain is that the black and white portrait on a table in his breakfast room (at least I assume it’s his breakfast room; a man of Wesley’s pretensions to feudalism almost certainly has a long oak table with high-backed chairs somewhere around that hideous house) is a portrait of his grandfather, as he announces without looking up from his breakfast when Dalton pauses in front of it.

“Looks like an important man,” Dalton says.

“He was an asshole,” Wesley replies.

This is one of my favorite stupid exchanges in the movie for a variety of reasons. Judging from the not just conciliatory but outright deferential tone Dalton adopts when he proclaims Grandfather’s importance—the “looks like” is just a turn of phrase, you can hear in his voice he’s quite certain it must be so—it’s quite possible that this was the last opportunity for peace in our time between the two most lethal men in Jasper, Missouri.

Despite enduring multiple physical assaults and murder attempts, despite seeing what Brad Wesley does to the woman in his life, this is Dalton attempting to meet Wesley where he lives, no longer just literally but emotionally as well. Surely, surely he can get this crazy old bastard to wax nostalgic about the lessons Papaw taught him, tough but fair no doubt, thunder in his voice but warmth in his heart, taught me the value of a dollar, when you forgive your enemies you create friends, you and me Dalton we’re not so very different are we?, you can hear it all play out in your mind just as clearly as Dalton could. Who would expect Wesley to grab hold of the proffered conversational life preserver long enough only to stick his ass into the middle and use it as a makeshift floating toilet before sending it bobbing on back? Not even the second greatest cooler in North America, I’ll wager.

Which is why I believe this to be one of the few occasions in which Dalton’s cooler-sense fails him.

Consider: His powers of observation, of sight and sound, of the sixth sense that can tell when trouble has walked through your door in knife-augmented boots, are unmatched at this point in the film.

Then consider: Here is the room he walked through in order to reach Brad Wesley.

What about this picture suggests to you that Brad Wesley uses the dead for decoration because he misses the time when they were alive?

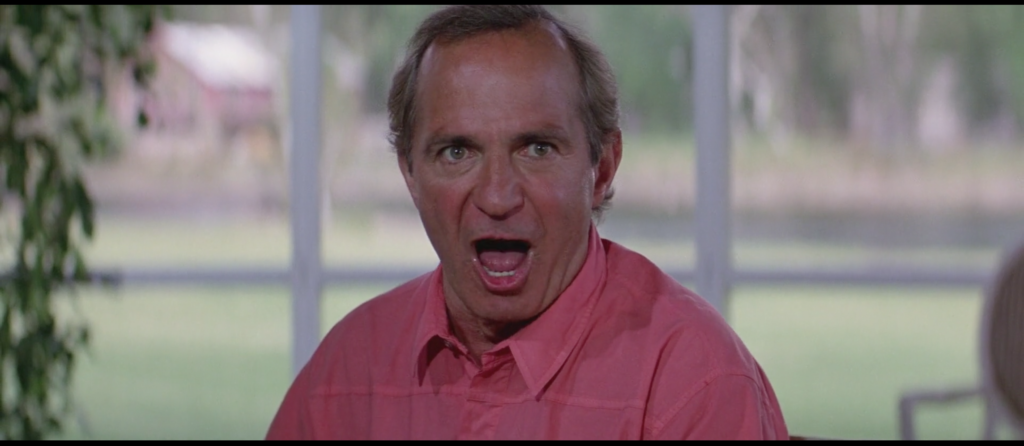

169. No Country for Poptimism

June 18, 2019“Will you shut that shit off?!” Brad Wesley yells. The “you” is unidentified, although Tinker and O’Connor snap to and head in the direction of the source of the problem. The problem is the upbeat ’80s dance-pop Wesley’s abused girlfriend Denise is blasting while she exercises, which she does with Fondaesque brio despite the bruises covering her face, neck, and chest, and the ensuing shame that causes her to cover up when Dalton sees. The source of the problem is therefore Denise, who’s playing the music in the first place. “I can’t listen to that crap,” Wesley explains to Dalton as his goons force his girlfriend to turn the brisk, bright, twitterpated tune off. “It’s got no heart!” Or balls, if you prefer, since that’s the body part to which Wesley later refers when he orders a command performance from Cody at the Double Deuce. During that performance, Denise is prompted to get on stage and strip, which she does with talent and enthusiasm. Then it’s Dalton’s turn to complain about Denise’s homage to Euterpe and Terpsichore. He refers to her as a dog who should be kept on a leash.

To the characteristically awful Wesley and the uncharacteristically mean-spirited Dalton, there’s nothing more aggravating than a woman enjoying art on anything approaching her own terms, even if it’s while working out to shake off the beating she received the night before, even if it’s taking off her clothes in front of a room full of baying strangers not for her own sake or her own financial health but to aid her abuser in his weird power trip. Music that lacks roots-rock authenticity, dancing that sexualizes the woman dancing with insufficient deference to the concerns of the man watching—these grave injustices must be stopped.

If Brad Wesley and James Dalton weren’t locked in a life-and-death struggle over a bar, they’d write one hell of a Black Mirror episode.

168. At the center of it all

June 17, 2019The speech in which Brad Wesley touts his accomplishments as a captain of industry to Dalton over breakfast and a Bloody Mary, revealing all of those accomplishments to involve the local establishment of downscale retail chains, is memorable for the obvious reason that this film’s chief antagonist says the sentence “Christ, JC Penney is comin’ here because of me!”

But that is not the only reason it stands out. Watch how cinematographer Dean Cundey (Jurassic Park, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Back to the Future, The Thing, Big Trouble in Little China, The Fog, Escape from New York) established Brad Wesley’s centrality to his own narrative by making him the center of the shot in which he spells out that narrative.

As Wesley rattles off his life story—coming up the hard way on the streets of Chicago, arriving in this nothing of a town after Korea, building it up into an empire of Fotomats, amassing both popular acclaim and a fortune in cash—the camera follows Dalton as he walks around Wesley at the perimeter of the round room in which he sits eating at a round table. It focuses on Dalton at the beginning of the journey, shifts to Wesley near the midpoint, and pulls back to Dalton at journey’s end. Their relative positions in the frame shift as well: Wesley starts at the left and winds up at the right, while Dalton does the opposite.

What is the purpose of this perspectival pas de deux, this theater in the roundhouse? To visually convey Wesley’s narcissism and his delusions of grandeur (which in the world of the film can be passed off for actual grandeur in a pinch). To emphasize the wary, hunter/hunted relationship between Dalton and Wesley, with their shifting focus and placement in the frame making it difficult to ascertain who is the predator and who is the prey. To show off the fancy house the locations team secured for the production. To give Ben Gazzara a platform on which to declaim without so much as having to stop eating his scrambled eggs. It is a truly accomplished shot, in the sense that it accomplishes a great deal. Is it any surprise that, depending on how one counts the opening and closing credits rolling over live band performances, it is at or near the exact center of the film?

167. Two pool tables

June 16, 2019There are two pool tables in the Double Deuce. There are two pool tables in Wade Garrett’s topless bar. There are two pool tables in Brad Wesley’s foyer. Yes, it seems like you can’t swing an uprooted stop sign in this movie without hitting one of every location’s two matching pool tables.

You have to respect the preparedness here, particularly on the part of Brad Wesley. Frank Tilghman and the unseen owner of the strip club might reasonably expect that patrons looking to unwind with a game of skill and chance might want to play pool in numbers sufficient to require parallel pool tables.

Wesley, though? That’s his home. His home! In his foyer where his mistress jazzercises, and his goons come to escort his nemesis. His home. The man has pool parties yes, but of an entirely different variety. And to go back to The Godfather, I can’t figure out a secondary meaning to their presence. Ceci n’est pas une orange.

Yet there they stand, the Jasper Argonath, the Pillars of the Fotomat Kings. They let all who pass between them know they have entered the realm the giver of gifts, the bestower of levity and liquor, the gamesmaster, building his parody of the recreations of every day folk, a grotesque satire, now perfected, the uruk-hai of billiards. Hither came Wesley, gray-haired, sullen-eyed, cigar in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the JC Penneys of the Earth under his sandalled feet.

159. The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades

June 8, 2019When Tinker and the Bleeder are sent to collect Dalton for an audience with Brad Wesley, they do so wearing bigass aviator sunglasses. It’s sunny out, I get that. But both these men have been badly beaten recently: Tinker by the bouncers at the Double Deuce, O’Connor by Dalton at the Double Deuce, and O’Connor again by his own boss, Brad Wesley, in the driveway of the very house to which he’s delivered his quarry. You can see a bandage sticking out from under the shades, in fact. Sadly he’s not the sort to wear concealer to cover up the bruise above his lip, but he’s trying his best to look healthy, together, and intimidating in front of two men who literally beat him unconscious on consecutive days. I get why: Abusers see weakness, and they hate it, and they exploit it, and it reminds them of the anger they felt when they inflicted the damage that caused the weakness and it makes them angry all over again, and god forbid word of what’s going on gets out.

I don’t mean to take this in such a heavy direction, but consider who else is in this scene.

That’s Denise, charming horny vivacious together Denise. The night before, she hit on Dalton with no regard for subtlety whatsoever: She saw what she wanted and went for it. From a personal emotional perspective it’s one of the most impressive things anyone does with anyone else in this farkakte movie, which frequently bears the same relationship to actual human interaction that Lego minifigures have to actual human hands. But it takes place in front of Jimmy, Brad’s bastard son [citation needed], who drags her strugging out of the bar, through the parking lot, and into a nearby vehicle. Jimmy gives the high sign to Ketchum and his squad of men who’ve ordered the Rooty Tooty Fresh ‘n’ Fruity at IHOP after church on Sunday move in to attempt to assassinate the man she just hit on by kicking his skull with a knife. Denise, it appears safe to assume, is brought back to Brad Wesley’s house, where he and perhaps Jimmy beat the living fucking shit out of her.

I’ll give Dalton this much regarding his conduct toward Denise, a definite character lowlight in many other regards: Seeing what Brad Wesley did to her seems to factor into his last-straw decision to react to Wesley’s overtures with open hostility. I say “seems” because he’s most visibly pissed off when Wesley brings up the fact that Dalton killed a man who’d discovered he was fucking his wife, and that could be enough. I’m just giving him the benefit of the doubt is all.

Anyway, you’ll notice no sunglasses have been afforded to Denise. No warning that Brad would be receiving company, either. She’s in the middle of an aerobics routine with music blasting when Tinker and O’Connor roll in with Dalton in tow, because getting beaten bloody by your boyfriend is no justification for an off day.

In conclusion, O’Connor and Tinker get off easy, and O’Connor gets murdered by the end of the movie. Throw some sunglasses on his corpse.

140. What’s better than this?

May 20, 2019Here, in a quiet moment near the end of the film just prior to the situation coming to a head so to speak, we see the goon in his natural environment. O’Connor, Ketchum, Morgan, Tinker, Pat McGurn: All of them have tucked their favorite short-sleeved shirts into their favorite pairs of jeans and settled in on the front lawn of the mansion owned by the Peter Pan to their Lost Boys, Brad Wesley. As you can tell from the shooting irons, this is not a company picnic or a cookout with the boys; they’re here to protect Brad Wesley from Dalton, whom they rightfully assume is on his way to kill them all because they murdered his best friend. You’ll have cause to wonder why, given the predictability of and ease of access to Dalton’s whereabouts—he in fact receives a phone call taunting him about the impending murder in the very location where that murder eventually takes place in his absence—they did not simply cut out the middleman as it were and murder him instead. Perhaps, given their superior numbers and lack of compunction about bringing guns to a knife fight and so on down the fight escalation scale, they did not split up to murder them both. Just blue-skying here: One could even imagine a scenario in which the large quantity of explosives the Brad Wesley organization has used to destroy Red Webster’s place of business and Emmett’s cottage could instead have been employed to blow up the Double Deuce (across the street from Red Webster’s store) or Dalton’s barn apartment (approximately two hundred feet away from Emmett’s house). It’s almost as if the goal were to deliberately goad the best fighter in Jasper into a mano a mano with a demented old man who likes JC Penney, reckless operation of motor vehicles, and music with balls. And if that were the case—well then, one would wonder, wouldn’t one, whether the very orchestration of such a plan signals a wish on the part of Brad Wesley’s men, or Brad Wesley, or some other and still more nefarious figure working behind the scenes, the hole in things, the Enemy, the piece that can never fit, there since the beginning, that Brad Wesley and his men be removed from the playing field permanently, and that if Dalton himself should die in the process of that removal, well, so be it.

But that’s crazy talk, isn’t it.

<Swearengen voice>Anyways,</s> the goons and their paymaster are to be congratulated on the success of their plan, which does indeed lure Dalton into the Wesley estate, at full speed, no holds barred, no quarter asked and none given. Few things will get an experienced killer in a killing mood than killing one of the men who trained them in the techniques that allow them to kill, and once the experienced killer is in that killing mood, he needs must find the people he desires to kill, and a good place to check is if one of them owns a mansion, then it’s that mansion. So kudos are due in that respect.

Until Dalton drops by, however, the goons are left to their own devices. Their mixture of vigilance and utter disregard for firearm safety is the purest visual expression of the goonsmanship levels evidenced in this film. Ketchum and the Bleeder? Silent sentinels, eyes at nine and six, ready for anything. Morgan, Tinker, and the sister-son? Holding a pistol the way you hold your phone when you’re trying to check the text that just came in but you’re doing a million things and you grab it at kind of an awkward angle but now you’re stuck with it that way until you put something else down, eating a lolipop, and scratching his back with the butt of a shotgun while saying “Remember that blonde? Shhyew. She could suck-start a Harley.” Ruthless efficiency coupled with a generated sense of wonder that any of these men lived past high school: That is the Way of the Goon. Bask in it.

Bask in it while you can, anyway, since all but one of these men will be dead within two and a half minutes.

139. Dress from an Italian Restaurant

May 19, 2019A bottle of white

A bottle of red

A smashed beer bottle on a drunk guy’s head

We’ll climb on tables with our feet

Near the chickenwire stage

You and I, filled with rage

A bottle of red

A bottle of white

Regularly scheduled thing for Saturday night

You’ll wear a tablecloth you got

From an Italian restaurant

Things were okay with me those days

I got a good job, I got out of Memphis

I fucked a dude’s wife, ripped out his windpipe

And I didn’t do time

Oh, we’d just met days ago

You’d just healed my torso

“Nobody ever wins a fight” was my pickup line

You remember those days getting nude in a refurbed barn

My enemy watched as we fucked on an old man’s farm

Oh, we didn’t bother to kiss, who needs foreplay when you’ve got charm

Cold beer, fist fights

My sweet romantic Jasper nights

Oooh, hoo

Yeah, yeah

Wooo, hoo

Ohh, ohh, ohh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh ohh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh

Dalton and Wesley were the hero and heavy

Of a film that initially bombed

Swerving around with the car top down

And tai-chi on the lawn

Nobody looked any finer

And they both put their dicks in the Doc’s vagina

But Jeff Healey knew and implied Doc was Wesley’s ex-wife

So it’s Dalton and Wesley and only one man will survive

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh ohh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh

Dalton and Wesley were getting real petty

In a film in 1989

Wesley decided to cut off the Double Deuce liquor supply

Everyone said they were crazy

Wesley had goons who were much too lazy

And Dalton was dueling a guy with a boot with a knife

Oh, but there were were watching Dalton call Wade for advice

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Well, he opted to send for his wise old mentor

Who had taught him to bounce with no fears

He’d feathered his nest where the girls shook their breasts

And drunk soldiers could ogle their rears

He was grizzled and louche and he said “Double Douche”

And his bloodstream’s primarily beers

A-whoa oh oh oh

Oh oh oh oh

Wade Garret’s old

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Well, they fought for a while in a very nice style

But it’s always the same in the end

Wade Garrett got knifed and it cost him his life

(Though he’d shown off his pubes to his friends)

Then the old men got mad and massacred Brad

Right after Dalton killed all of his men

Oh oh oh oh

Oh oh oh oh

Dalton and Wesley had had it already

By the end of 1989

There was no way to know

We’d be watching this show

For the rest of our lives

It influenced Mystery Science

Extensively cut for network compliance

And soon was a staple of watching on cable while high

Oh, and that’s all I heard about Dalton and Wesley

One was Gazzara and one was real sweaty

And here we are waving Dalton and Wesley goodbye

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh ohh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh ohh

Oh oh

Oh oh

Oh oh oh oh ohh

Yeah, yeah, yeah

A bottle of red

Ooh, a bottle of white

Whatever works so pain don’t hurt tonight

Just wear that tablecloth you got

From an Italian restaurant

113. Pants

May 13, 2019Brad Wesley’s pants are a mess. Look at those wrinkled-ass trousers. Like an elephant’s trunk, twice, in khaki. This is his apotheosis right here, his truest moment of pure power, the point at which instead of blowing up buildings in the middle of the night with no one looking he feels able to order his man to run over a Ford dealership in a monster truck in broad daylight with a crowd of like two hundred witnesses watching. Dalton’s there, the owner of the Ford dealership is there, Wade Garrett is there, his own ex-wife Elizabeth is there, and guess what, the man don’t give a fuck, this is his town, don’t you forget it, but apparently the dry cleaners is not included. Those pants are the visual equivalent of him crowing about having the raw kingmaking power to open a JC Penney. What the hell was Ben Gazzara doing to wrinkle his pants up like that? Did no one from wardrobe intervene? Did they think it made for a nice feet-of-clay visual shorthand and just let it slide? Jimmy, couldn’t Jimmy have said something? Ketchum, a man who looks like he was born starched, what about him? Will no one tell Brad Wesley his pants are embarrassingly wrinkled? Is this what it feels like to be truly alone, even with the world at your feet? Standing in front of your great triumph over your enemies and looking like a goddamned fool and you have no friends to say so? What? Is up? With the pants?

The Stand is Stephen King’s best book, I decided about three decades into my career of reading and re-reading Stephen King books. One of the many reasons I think this involves a fellow name of Starkey. Starkey’s a military guy, brass, way up on the totem pole but it’s a totem pole they keep hidden in the dark at all times. He was in charge of the bioweapons project that had a little hiccup and started to destroy the human race, and so he’s in charge trying to halt that destruction. He’s also in charge of trying to cover it up, first under the pretext that it will buy them a few extra days to find a vaccine or a cure before panic sets in, and then mostly out of sheer force of American military habit.

The thing about Starkey is that as time goes by and it becomes increasingly clear he won’t be earning any medals for this one, to say the least, he grows fixated on the security monitors that show him the inside of the facility where Captain Trips emerged and started drowning everyone in their own snot while their brains boiled. At first this happened much faster than it does later, for reasons that I don’t think the book ever quite makes clear, and even if it did the idea of a flu virus that kills in under a minute the same way a regular flu virus would kill over the course of several days is science-fictional even for The Stand.

Be that as it may. The important thing for Starkey, less important than other things really but increasingly important to him as the bodies pile up outside that’s for sure, is that one of the people in that facility died in the cafeteria, just dropped dead at his seat, and when he did his face fell right into his bowl of soup. The soup starts congealing and getting really disgusting, which is the case with everything else that used to be warm and made of organic material down there, but the soup and the face in the soup are what start to bother Starkey, and bother him bad.

It’s the indignity of it, you see. This fellow in the lab, for all anyone knows his face will remain in that bowl of awful soup for…well, for as long as it takes for the site to be deemed sterile enough to enter at first, and then, when it becomes clear no one will be left alive to enter it, for all eternity. Starkey just stares and stares at this guy with his face in the soup. Did I mention Starkey also gave the order to have secret agents in Russia and China open vials of the flu without ever telling them what they were doing, just to make sure that when America dies she takes the rest of the world with her? Yeah, but anyway the soup. It’s just not right, a man dying like that, like a slob, like a joke. Something must be done.

Anyway, I’ve been thinking a lot about Brad Wesley’s pants. They’re wrinkled, is the problem. See? See? See?

120. Life Is Good, or The Apotheosis of Karpis

April 30, 2019For the past week I’ve chronicled sixty seconds in the lives of Mr. Wade Garret and Dr. James Dalton. (For the purposes of this conversation I’m assuming his degree in philosophy from NYU was a Ph.D.) During this pivotal minute, Dalton calls his old friend and mentor Wade to ask if he’s heard anything about a guy by the name of Brad Wesley. At this point, friends, you and I have talked about Dalton’s initial encounters with the richest man in Jasper: watching him buzz Emmett’s horse corral with his helicopter, swerving out of the way as he sings doo-wop while driving into oncoming traffic, shaking hands and having a brief conversation at Red Webster’s auto parts store, beating the shit out of several of his minions after they try to stab him to death in an attempt to make the Double Deuce re-hire a bartender. I’d say he’s handled all this rather well. What, you might be wondering, occasioned his call for counsel?

These happy assholes.

Dalton catches two of Brad Wesley’s premier goons, Jimmy and Karpis, just as they pull out of Red’s parking lot. Karpis, whom we see exiting the store, has just busted the place up, spilling various motor oils and antifreezes and whatnot all over the place as punishment for Red’s recalcitrance in paying his full “contribution” to the Jasper Improvement Society, the legal name of Wesley’s protection racket.

“Work ain’t work when you’re havin’ fun,” Jimmy says from behind the wheel of the getaway car as Karpis hops in after doing the deed.

“Life is good,” Karpis confirms.

And like that—poof—he’s gone.

One last, lingering, smoldering staredown at Dalton later, Karpis is driven away from the store and right out of the movie, forever. It’s the last we see of him, much to my chagrin, handsome devil that he is.

But oh, his legacy! What Karpis does this day puts Dalton and Wade on a collision course with Jimmy and Wesley, their opposite numbers. The explosion that results, which includes multiple literal explosions, will leave three of those four men dead, and change the face of Jasper forever. And Karpis’s mesmerizing face that sets it all in motion. In that Cheshire Cat grin, I see the future: Life is good, but all men must die.

114. The Nine

April 24, 2019Nine quarters, says the sign that appears in the middle of Dalton’s pivotal conversation with Wade Garrett, right after he blows off the threat presented by Brad Wesley. Right away we can see that reality has warped a little, that a glitch in the matrix has appeared. As well it might: Dalton has just underestimated his opponent and failed to expect the unexpected, a violation of his own First Rule. And for that, a price must be paid.

But what if there’s more to it than that?

It was not I who set myself on this path, but reader @RoddySwears. It was he who noted the numerological significance of the established price. Nine quarters. Two dollars and twenty-five cents. $2.25. 2 + 2 = 9.

What could such a specific prophecy mean?

Then I realized.

The Nine are abroad.

113. Signs

April 23, 2019Dalton goes to a laundromat to make his phone calls. There’s no phone in his luxury barn, we know this from Emmett’s anti-sales pitch when he rents the place. Either he doesn’t have opening privileges for the Double Deuce or he wasn’t in that part of Jasper (the Auto Parts/Boat Sales/Hellhole district) when he needed to make the call. Either way, here he is, inside this beautiful laundromat that I’m almost positive you couldn’t find somewhere in California in 1989 or thereabouts, reaching out and touching his mentor Wade Garrett. He’s wondering if Wade’s heard anything about a guy named Brad Wesley, because (I’m inferring) any man who’d make trouble for a cooler stands a decent chance of having been watchlisted by veteran cooler agents across the country. Wade comes up empty, though using his cooler-sense he asks Dalton if he’s gotten into any kind of trouble. “Nothing I’m not used to,” he says, before adding with a chuckle “but it’s amazing what you can get used to, isn’t it?” Wade banters back, they say their goodbyes, that’s that.

But look what happens after Dalton says Brad Wesley is nothing he’s not used to.

Suddenly a sign appears where none had been before. The sign lists the cost of using one of the laundromat’s large machines: NINE QUARTERS. I never noticed this until just this afternoon.

So here’s the situation. You can choose to believe this is just the kind of harmless, almost invisible continuity goof that happens in nearly every movie.

Or you can take it as a sign [pause for reader recognition of the awesome implications of the connections being drawn here] that for dismissing Brad Wesley, a price must be paid.

Search your cooler-sense. You know what is true.

109. We’re not so different, you and I

April 19, 2019“What he says, goes.” “It’s my way or the highway.” “It’ll get worse before it gets better.” Few action-movie cliches go unuttered in Road House, along with several no action movie has ever used before or since. (“I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick.”) Remarkably, however, we never get a good “We’re not so different, you and I” out of Brad Wesley. There are moments when it seems he’s coming close—Mike Nelson notes this during the climax in his excellent solo RiffTrax on the movie, the first of three or four he and the other MST3K vets have recorded—and the Doc draws the parallel herself when things get really hairy, but the villain whose specialties are taunting Dalton and opening JC Penneys never goes there.

Given Rowdy Herrington’s direction, perhaps actually coming out and saying it would be gilding the lily. No, no one says “We’re not so different, you and I.” But in scene after scene both Dalton and especially Wesley react to annoyances and misfortunes with the exact same way. They cock their head to the side, shake it in “get a load of this” disbelief, and half-smile “ya just gotta laugh”–style. Dalton does it when he emerges from the Double Deuce after his first night of work and discovers his car has four flat tires, a broken antenna, and a shattered windshield (Nelson, in his RiffTrax again: “I have hours of backbreaking labor ahead of me. It’s actually pretty funny!”); Wesley does it the very next day when he spots Dalton practicing tai chi. You get variations on it for matters as minor (no pun intended) as Dalton finding Steve in flagrante with a young lady in the back room, and as grave as Wesley walking through his mansion and discovering the dead bodies of all his henchmen. Wade Garrett and Elizabeth may not do the head-shake thing but they spend the entirety of their three-person date with Dalton grinning at each other in that same can-you-believe-it way.

It can hardly be said that Ben Gazzara and Patrick Swayze have similar acting styles or training, so I can only assume this was Harrington’s go-to instruction, like George Lucas’s infamous “faster, more intense” on the set of Star Wars. But like so many of the film’s other foibles this winds up feeling both endearing and unique. Vandalism, tai chi, dead bodies, people fucking during their 15 minutes—Road House‘s reaction to each is “grin and bear it,” and there’s no other film with quite so untroubled an outlook on the totality of human experience. As Red Webster put it, “That’s life. Who can explain it.”