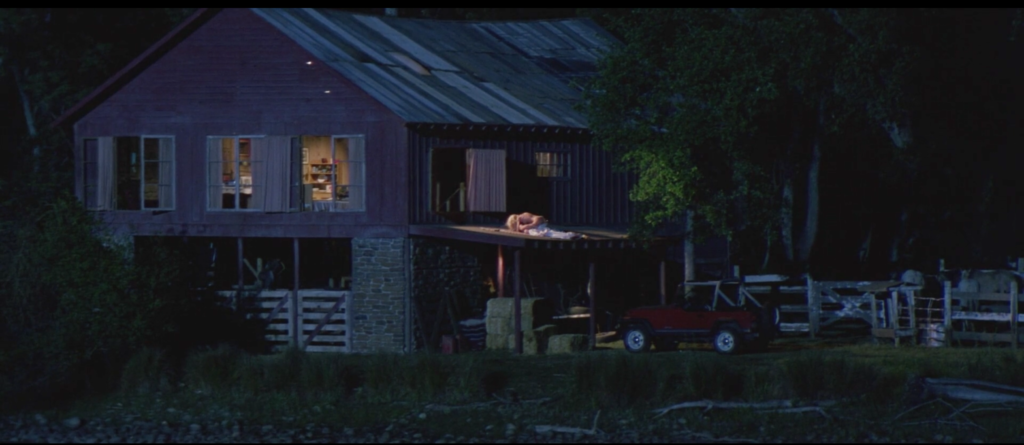

Dr. Elizabeth Clay isn’t the only person who registers the significance of the location of Dalton’s apartment on this fateful night. Across the water, her ex-husband Brad Wesley watches intently, liquor at the ready, as Doc slithers out from under her makeshift sheet-robe and mounts Dalton for a second bout of lovemaking. He rocks back and forth in his rocking chair, stops—perhaps to avoid any unpleasant mimesis of the movements of the people upon whom he’s spying—and reaches for a cigar, because even a broken Freud gives the right time twice a day.

The question that interests me here isn’t why Brad Wesley is watching his nemesis fuck his ex-wife, but when he started watching. Unless he snuck out onto his balcony or lanai or whatever it is in a big hurry after the Doc looked across the water and saw his house before she and Dalton did their standup routine, it’s doubtful he caught round one. This means Wesley started peeping at some point between then and now, a time period during which Dalton was awake and alone and bare-ass naked on the roof while Elizabeth slept the sleep of the peacefully post-coital in Dalton’s bed. It means he was watching Dalton all by himself.

This tracks with Wesley’s dialogue in the remainder of the film, for what it’s worth. At no point during his many interactions with Dalton during the rest of the movie does he bring up the man’s relationship with Elizabeth, not even at times when it would be natural to do so—when he playfully upbraids Dalton for “taking all my boys” following the cooler’s murder spree through Wesley’s goon army. “Hell, you took my girl, too”—easiest thing in the world to say, but he doesn’t say it.

The closest he comes to admitting any jealousy whatsoever is when he tells Elizabeth how much he hates to see her wind up with a no-account drifter like Dalton. As I’ve written before, this isn’t the “if I can’t have you no one can” speech you’d expect at all. It’s not hard to imagine Wesley wishing he could have her again, but that’s just it: You have to imagine him wishing it. The focus is on Dalton, and whether or not he’s a worthy successor to Wesley in Elizabeth’s love life.

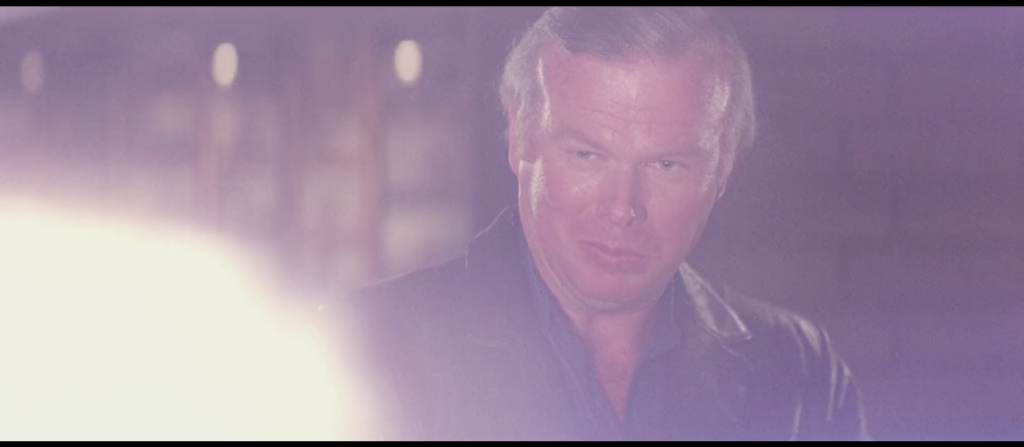

Which brings us back to Peeping Brad here. By now he’s gotten himself quite an eyeful of Dalton—Does he find the man lacking as a lover and thus unworthy of Elizabeth’s love? Or is it the opposite? Is Dalton so toned and hung and prodigiously talented in the sack that Wesley worries his ex has been dickmatized by someone with little else going for him? Or is this masochism—a case of Wesley rubbing his own face in the happiness of his former lover and his current arch-enemy because some part of him is addicted to misery?

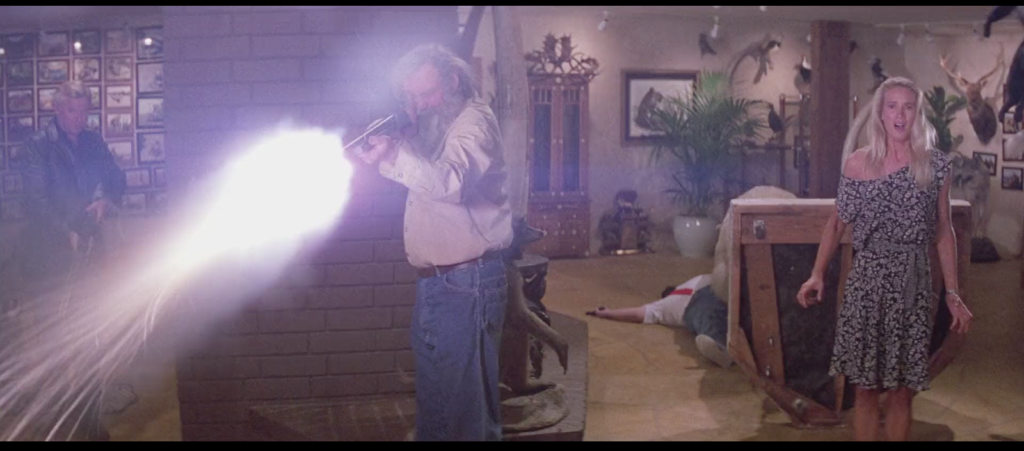

Then there’s this tantalizing possibility: The Elizabeth stuff is a smokescreen for sexualized resentment of and desire for Dalton himself. In this reading, when Wesley tells Dalton that the only thing missing from his trophy room is his ass, Wesley really wishes he could get Dalton’s ass stuffed and mounted the old-fashioned way. To be honest Wesley strikes me as a drearily heterosexual figure, double-entendre action-movie homoeroticism notwithstanding. But this leaves open the possibility of simple envy, of Wesley covetously devouring Dalton’s body and beauty with his eyes.

Wesley spying on Dalton and Doc having sex on the roof of a barn is a crime of opportunity, that much seems certain. But it is difficult to say with any certainty at all why Wesley seized the opportunity. Grab a cigar and ponder this imponderable with me.