Over at Comic Book Resources, I talked with J.M. DeMatteis about writing Spider-Man in anticipation of our (!!!) comic Marvel Adventures Spider-Man #19 — in stores tomorrow!

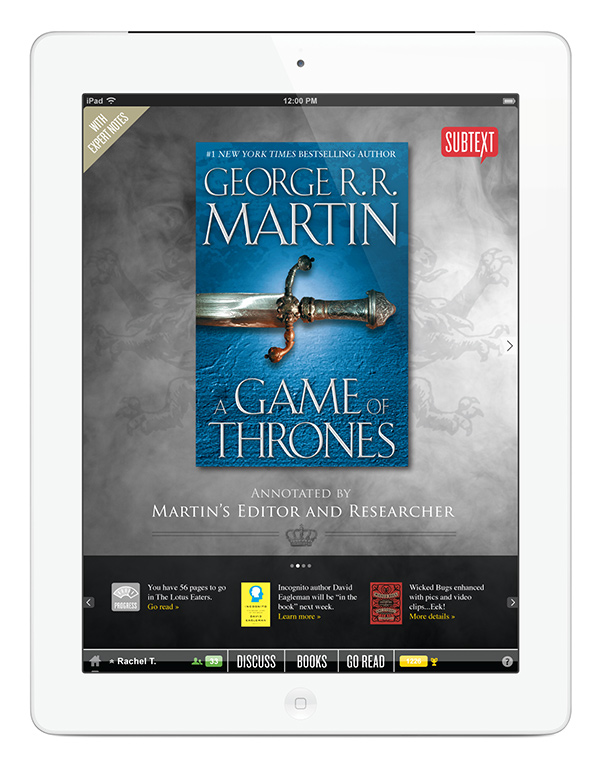

The Annotated A Game of Thrones

I’m over the moon to be able to finally announce this: I annotated A Game of Thrones.

I didn’t do it alone, either. Working alongside me were Anne Groell, editor of the entire A Song of Ice and Fire series; and Elio Garcia, George R.R. Martin’s go-to researcher, the co-founder (with Linda Antonsson) of ASoIaF megasite Westeros.org, and the co-author (with GRRM and Antonsson) of the forthcoming World of Ice and Fire guide.

I know, right?

We did this in a very cool fashion for a very cool new iPad app called Subtext, which launches today. It’s kind of like having a social network built into the book itself.

The way it works is that you download Subtext for free from the iPad App Store. Then you use it to read any Google Books ebook. As you do so, you can embed notes in the margins at any point throughout the book, sharing your thoughts or asking questions about what you’ve read. You can also read and reply to any notes on the book left by your friends, or in cases like A Game of Thrones, notes left by the author or by experts like, well, me. This video will give you the basic idea.

So in other words, it’s not just that you can read an annotated version of A Game of Thrones — you can annotate it yourself, and interact with anyone else who’s done so, including Anne, Elio, and myself. And a whole bunch of other books featured in the launch have expert or author annotations as well. (George was a bit too busy to contribute himself, which is why we three were tapped. Somehow I don’t think you’ll mind that he didn’t find time in the schedule.)

If you’ve enjoyed my writing about A Song of Ice and Fire here or at All Leather Must Be Boiled or anywhere else, I think you’ll enjoy the notes I’ve left for you to find.

But speaking personally, my contributions kinda pale in insignificance compared to Elio and Anne’s. When I was first approached about the project, I said yes in large part just for the opportunity to work alongside such august personages in the ASoIaF community. I was not disappointed. Anne’s you-are-there anecdotes about discovering the book, working with Martin, and what she knows (and doesn’t know) about what has yet to be written are worth the price of admission alone. (And I’ll tell you what, there’s little that does your superfan ego better than being told by the book’s editor that this or that insight you had about the book was dead on.)

Elio’s astonishingly comprehensive annotations are also more than a return on your investment. He’s provided the first appearance of nearly every character, House, region, and in-world jargon with a capsule biography/definition and a link to further information on his and Linda’s indispensable ASoIaF website, Westeros.org. And as GRRM’s researcher and soon-to-be coauthor, the guy who knows Westeros better than Martin himself, he too offers unique insights into process, theme, and technique.

In both cases, just reading their notes as they went up while I was working on the project was an enormous pleasure. God only knows how much of that AT&T data plan I ate up by anxiously refreshing the Recent Notes page to see if Anne or Elio had dropped any more knowledge bombs on me. And my desire to earn my keep alongside them led, I think, to some of my best ever writing on the book.

I really hope you iPad owners will check it out. Download the app here, then download the book here, then go to town. Our annotations should pop up automatically — keep your eye out for my sigil.

See you in the pages!

PS: Thank you to Elio Garcia for recommending me for the project, thank you to Elio and Anne Groell alike for treating some dude with tumblr like both a peer and a pro, and thank you to Claire Teter from Subtext for guidance and support throughout the process.

Brief Boardwalk Empire thoughts

SPOILERS AHEAD

I’m really admiring Boardwalk Empire‘s narrative audacity this season, from a structural perspective. Last season’s cliffhanger was that Jimmy, Eli, and the Commodore were conspiring to take Nucky down. My assumption, and everyone else’s I assume, was that we’d spend much of Season Two watching this happen. It’d be a slow race toward the final coup attempt: the conspirators working to keep their plans secret before the trap is sprung, Nucky working to stay on top and get to the bottom of the setbacks that would surely start to befall him.

Instead, the coup happened in the season premiere. It turns out Nucky’s too big to take down in one fell swoop, but that aside, he learned that his brother, mentor, and protege had all betrayed him; that the city bigwigs were backing his enemies; that he was all alone, with his money and clout in serious danger. Instead of whether the coup would take place, the season is about what happens afterward. Smart stuff.

So too is the arrangement of the warring parties. In a battle between Nucky and Jimmy, there’s no default for the audience’s sympathies. Nucky’s the guy in the credit sequence, but the story we were really sold from the beginning is the story we’ve seen many times before — the hungry young man on the make. In other words, there are two protagonists, and after watching them work together for a full season (albeit with some hiccups), we’re now watching them become one another’s antagonist. Who do you root for? What’s more, their primary allies on the criminal end of things are the show’s two most compelling such characters, Chalky and Richard. We’re obviously to root against the conniving, child-raping Commodore, and the politicians on both sides aren’t worth spit, but there really is no easy way to take sides between the primary players. Obviously there are plenty of big prestige cable dramas who at least attempted to split audience sympathy between rival factions, but for the most part there were still clear good guy/bad guy lines established initially, regardless of where things went from there — sheriff versus crime boss, cops versus druglords, stern but kind Northerners versus arrogant, hedonistic Southerners. Boardwalk Empire has really split things down the middle, and I’ve got no idea what side I’m gonna come down on. Mostly I hope for a rapprochement. Don’t you?

Carnival of souls: Marvelcution ’11, more Sexbuzz, Jonny Negron does Drive, more

* Alejandro Arbona and Jody LeHeup, two of Marvel’s best editors and the men responsible for Invincible Iron Man & Immortal Weapons and Uncanny X-Force & Strange Tales respectively, were laid off by Marvel yesterday, among many other employees of long standing. I’ve been pretty upset about this. Comic Book Resources provides the facts; Tom Spurgeon and Heidi MacDonald provide much-needed and highly infuriating context.

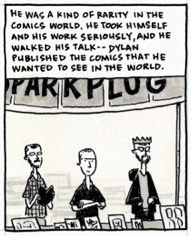

* “Dylan [Williams] said something once that really stuck with me. ‘Art isn’t bullshit and love isn’t bullshit.’”—Austin English

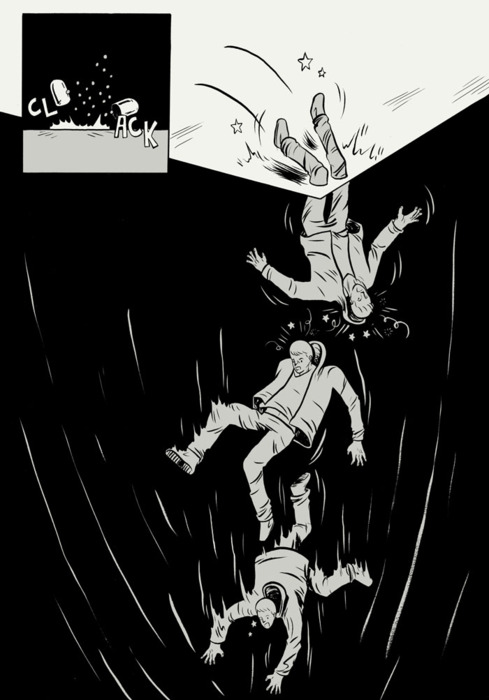

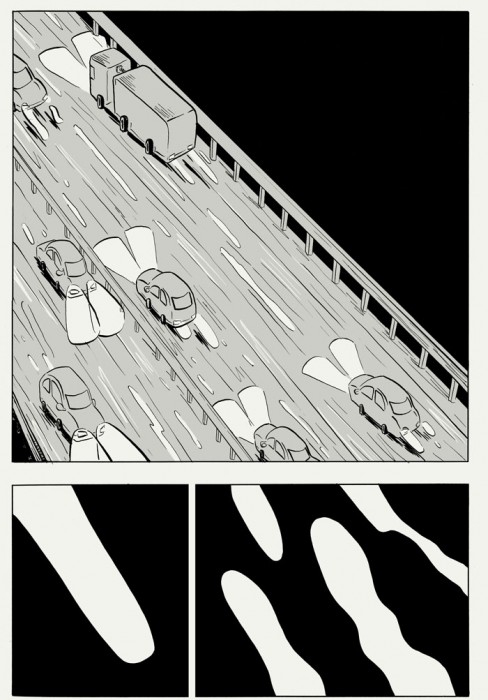

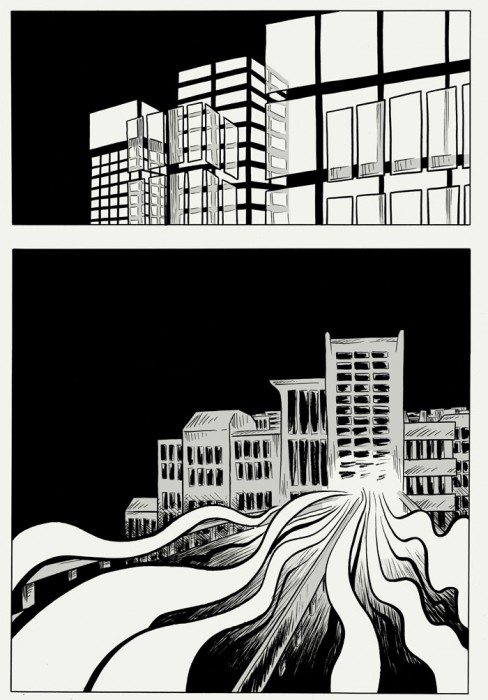

* Wow, speak of the devil: Andrew White has posted the complete Chapter Five of Sexbuzz.

* Vasilis Lolos is prepping a webcomic called Supersword, the goal of which, he says, is “Lord of the Rings for the Nintendo generation.” Sure, I’ll eat it.

* Well, it happened: Jonny Negron saw Drive. AND THE REST IS HISTORY.

* Tom Gauld’s doing a book for Drawn & Quarterly? Tom Gauld’s doing a book for Drawn & Quarterly!

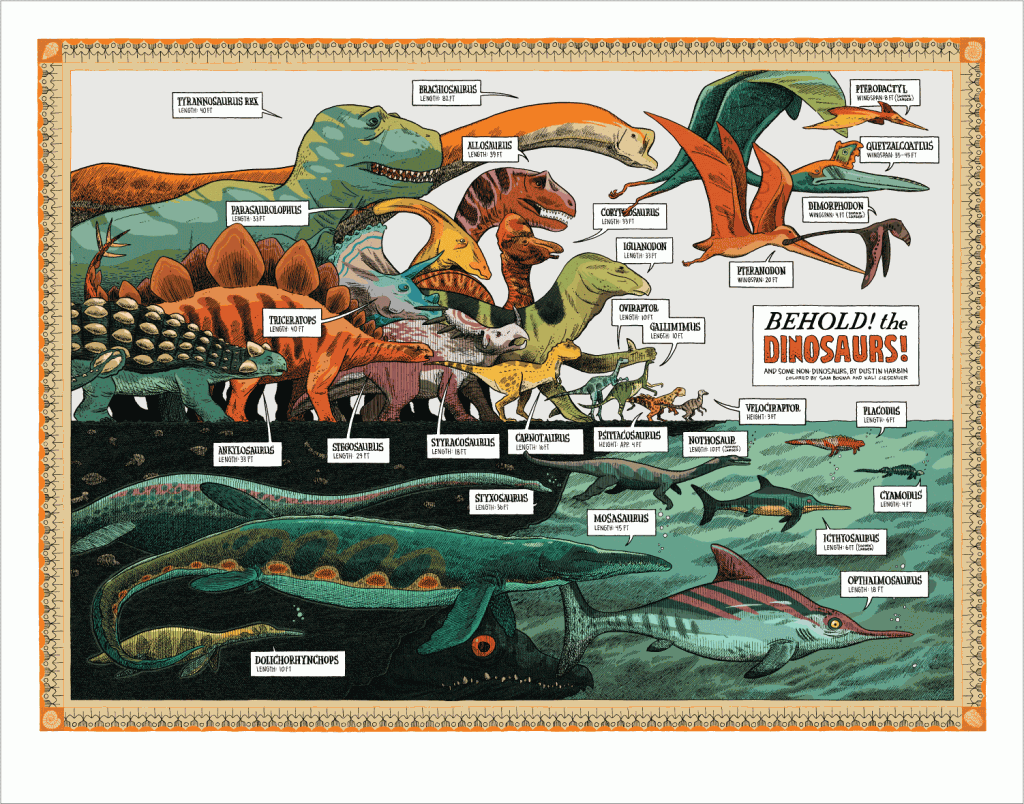

* Dustin Harbin drew some dinosaurs, Sam Bosma and Kali Ciesemier colored them, and it was good.

* Whoa: Matt Zoller Seitz says the new Kelsey Grammer drama Boss is a great show.

* The great cartoonist Jason lists his five favorite giallo actresses and posts a picture of Edwige Fenech for emphasis. Paging Dr. Purcell, Dr. Curt Purcell!

* Happy birthday to Mike Baehr of Fantagraphics. Like so many Fanta employees, he’s one of the good ones.

* Real Life Horror: I guess we’re sending flying killer robots to execute American teenagers from the sky at will now, which is super-fucking-exciting, isn’t it.

* Wow, Uno Moralez has really outdone himself with this image gallery. It’s called “Horny Goblyns,” and it makes the abbreviation NSFW a comical understatement.

* Sex, synths, teen angst/lust, eldritch horrors: Is there anything about Jérémie Périn’s video for “Fantasy” by DyE that isn’t one of my favorite things? (Hat tip: Steven Wintle.)

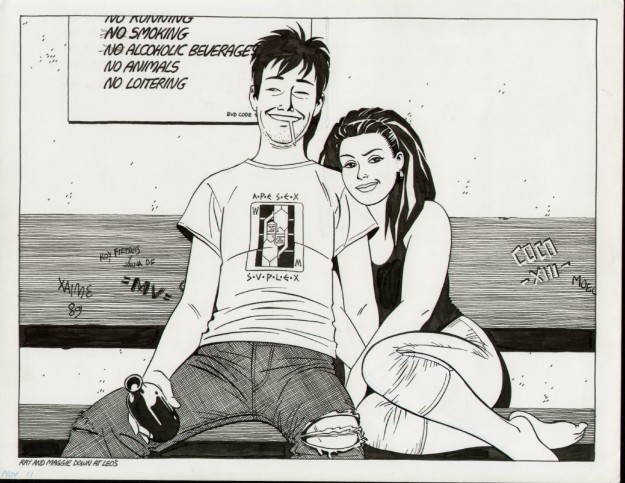

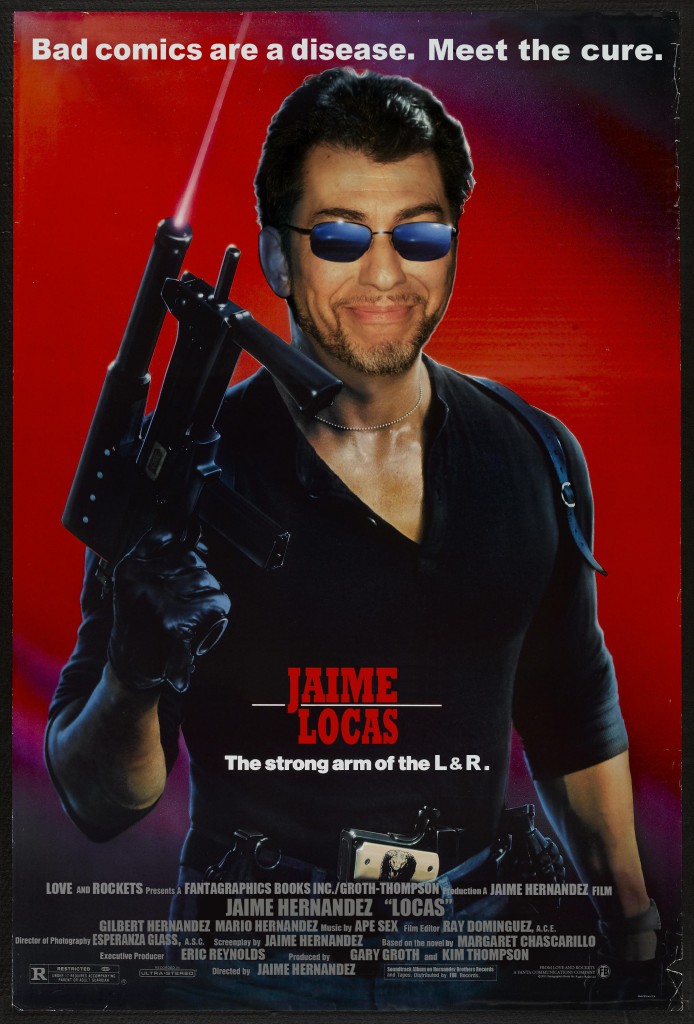

You’ve come a long way, Jaime: or how I learned to stop worrying and love Love and Rockets

I wrote about “getting into” Love and Rockets for Robot 6. It’s the culmination of a week’s worth of posts on the subject. Take a look.

Comics Time: Ganges #4

Ganges #4

Kevin Huizenga, writer/artist

Fantagraphics/Coconino Press, October 2011

32 pages

$7.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Jaime Hernandez, Jeet Heer, Michael DeForge, Uno Moralez, more

* I posted a rundown of all the things I’ve been working on lately over on my A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones blog All Leather Must Be Boiled. Keeping pretty busy!

* BAD COMICS ARE THE DISEASE. JAIME HERNANDEZ IS THE CURE. I’m going full-court-press on Jaime and Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 this week, in case you hadn’t noticed. The latest:

** Springboarding off Tom Spurgeon’s excellent piece, I talk about Jaime as a literal alternative comic for disgruntled or jaded readers.

** And springboarding off Jeet Heer’s excellent catch-all column for The Comics Journal, I talk about “The Love Bunglers” as a potential career capstone, and Gilbert’s comics as an under-the-radar phenomenon of comparable quality and import vis a vis his thirty-year storyline.

* There’s lots more to talk about in Heer’s post, by the way. I’m particularly struck by his argument that the work of contemporary cartoonists on classic reprints in a design, editorial, or critical capacity helps fold those works into the current practice of comics the same way a Scorsese riff on Welles or Eisenstein does in film. It comes as a riposte to some bombthrowing on the topic of contemporary vs. classic cartoonists, too, and you know I always like to see bombthrowing defused.

* Also on the L&R tip: Matt Seneca on the bravura mirrored sequence in “The Love Bunglers.” No, not that bravura mirrored sequence — the other bravura mirrored sequence.

* Yeah, I’m pretty happy about Sexbuzz.

* Ben Katchor’s latest comic takes on the 1%.

* Like the Geto Boys, Michael DeForge can’t be stopped. He’s posted a new installment of Ant Comic, while his wondrous horror minicomic SM is now up in its entirety on Jordan Crane’s What Things Do. Jesus but his line really pops against that cream background.

* The good news: Ross Campbell has finished Wet Moon 6, the latest volume in his engagingly morose and meandering goth slice-of-lifer. The bad news: It’s not coming out until October 2012.

* A day may come when I don’t link to a new Uno Moralez image/gif gallery…but it is not this day.

* Speaking of Moralez, I don’t know if Google Translate is steering me right, and the post itself is showing up in my RSS reader but can’t be accessed directly, but a post that features the image below and appears to state that Moralez is self-publishing a collection of his work is too good not to at least try to share.

* I love Matthew Perpetua precisely for posts like this one. In one fell swoop he singles out the best song on the new album by retro synthgazer guy M83 and quickly describes why it’s good, while also explaining why his overall project never quite gets off the ground:

Their new album, a double disc set, is sprawling and “epic,” but its expanse is mostly numbing – a few setpiece numbers are surrounded by ethereal time-wasters and underwritten bombast.

That is exactly right, and it’s been exactly right for at least three albums running now. In theory M83 could not be more up my alley, and from single to single he’s one of my most listened-to artists of the past decade (up until now, that is — I’m not crazy about “Midnight City”; too much yelping), but in practice his albums feel overlong, undercooked, and too content with his (admittedly) great idea for a musical aesthetic to actually execute that idea well. But yeah, “Claudia Lewis” is pretty terrific.

* If you know the source of the image, this is one of the funniest Kanye + Comics entries ever.

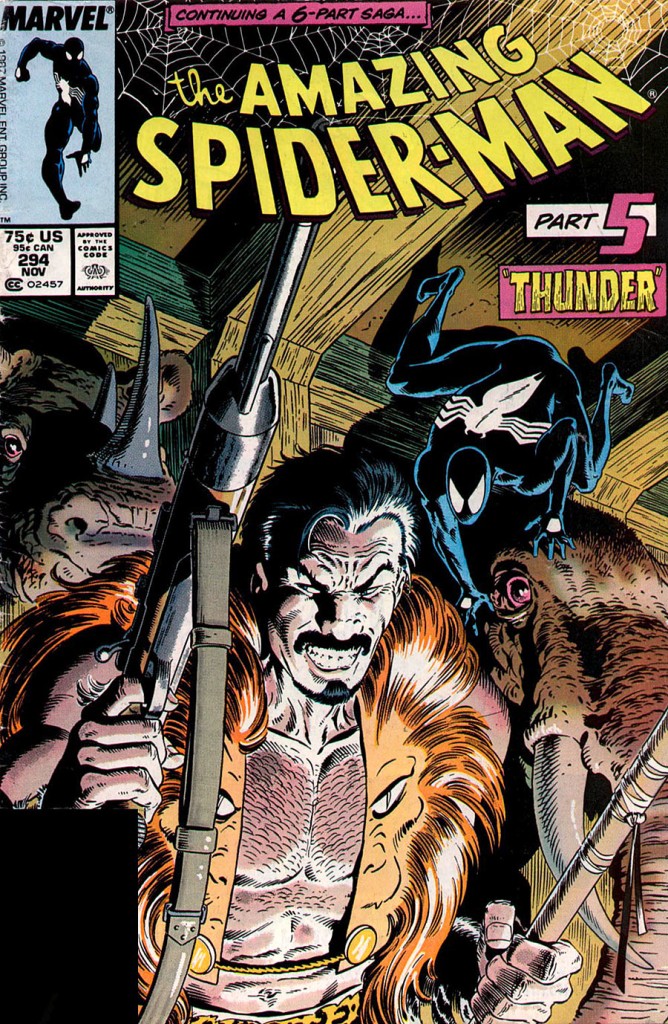

A friendly reminder from Kraven the Hunter

One week from today, I make my Marvel Comics debut with “The Amazing Spider-Man in…The Hundred-Story Hunt,” the back-up feature in Marvel Adventures Spider-Man #19. Illustrated by Pere Pérez, it’s a battle between Spidey and Kraven in a high-rise office building. Hey, write what you know!

It’s not Kate Beaton’s take on ol’ Sergei Kravinoff, but it’ll do. I hope you buy it and enjoy it.

Mad Men thoughts: Special “…and the John Deere you rode in on” edition

* Just finished Season Three, Disc Two. SPOILERS AHEAD.

* I’ll admit it: I’m looking forward to being able to type “Mad Men” into Google and go berserk the moment I finish the series so far almost as much as I’m looking forward to the act of finishing the series itself. For years now I’ve been very studious in avoiding talk about the series (I lead a life lived in terror of spoilers, basically.) But even so, some things slip through the cracks — and sad to say, Roger Sterling in blackface was one of those things. Because I’m usually so careful I have no idea how I came across the image, but sure enough, a couple of weeks ago a Google image search revealed Roger doing his best Al Jolson. I winced for many reasons, but “Aw, shit — that would have come as a complete shock otherwise” was not least among them.

* Fortunately (if that’s the right word), enough time had passed that I sort of forgot the moment was coming, and when it did come it was more than shocking enough on its own terms. Literally jaw-droppingly shocking in fact. I sat there on the train staring at my laptop catching flies as dapper, jolly, funny, skeevy, charming Roger Sterling serenaded his bonnie bride with centuries of unthinking racial animus and privilege smeared all over his face. I think my main thought was “blarrrrrrgggghhh.”

* I think that was Don’s main thought, too. The big question, I suppose, was what made Don more uncomfortable: Roger’s heedless racism, or his heedless foolishness? It’s the foolishness that Don smacks Roger around for at the end of the episode, but his conversation with the incognito Conrad Hilton at the club’s abandoned bar indicates a lingering sense of solidarity with the help, no matter who they are. As was perhaps the case when he ignored Sal’s hotel-room indiscretion, I get the sense that the only thing that makes Don judge a person is incompetence. Insofar as bigotry blinds one to the feelings of a class of other people who could otherwise be engaged and thereby communicated to as an audience, bigotry is a form of incompetence, and that’s what matters.

* I did permit myself a bit of googling after the episode was over, and a quick search for “Roger Sterling blackface” revealed some pretty shallow and facile thinking about Mad Men‘s approach to race prior to the episode. I’m both amazed and not at all surprised that people who get paid to write about these things mistook the way the show reduced African Americans to speak-only-when-spoken-to servants, or to saintly nannies turned to in times of crisis, or to evidence of one’s beatnik bonafides, as evidence of the show’s racism rather than as an indictment of the characters’. Apparently episodes in which the characters gathered ’round the TV and talked about Birmingham would have been “better” than showing how they’d created a world for themselves where black people were permitted to exist at the margins but no further. I dunno, man. If that’s not an intentional absence, I don’t know what is. And watching it slowly leak into their lives as a presence — Betty’s drug-induced vision of the sad, slain Medgar Evars; Pete Campbell’s incredulity that anything as irrational as not wanting to be seen as the Negro TV company could ever trump the making of money; Paul’s failure to maintain a romantic relationship that needs must exist as more than symbolism and platitudes — has been bracing.

* Elisabeth Moss is a terrific actress because the role she’s playing is so challenging for a person of this day and age to play. She has to play Peggy as a strange and alien creature called a “woman,” learning and fighting to become a “human,” a transformation basically without social precedent.

I’ve been thinking a lot about sexism lately — I’m watching Mad Men, reading about superhero comics, and raising a baby daughter, so how could I not? And I’ve realized that I believe women are different from me as a man in three very specific ways and those three very specific ways only:

1) They have slightly different biology.

2) They identify as “women.”

3) I find some of them sexually attractive.

As best I can tell, that’s it. Aside from those three things I’ve never encountered a difference between myself and a woman that couldn’t be explained as a facet of that particular woman as an individual person rather than as a facet of her woman-ness. I remember discovering my senior year in college that one of my roommates had deliberately never taken a course taught by a woman professor unless required to, and this totally blew my mind — it quite literally never occurred to me that women as a class would be less good than men as a class at anything other than, like, bench pressing. I’m not saying this to pat myself on the back because I in now way feel like I deserve any “credit” for this viewpoint, any more than I deserve credit for having blue eyes. I did no work to get here. It’s just the way I see things, even if I’m only now articulating it in precisely this way, and mentally I never had the option of seeing it some other way, I don’t think.

The point is that problems arise when men think of women as a separate species. When Peggy looks at Don and sees who she wants to be, not who she wants to be with, for most men in the office that’s akin to a chimpanzee putting on pants.

* One variable I’d forgotten when trying to pinpoint the origin of Pete and Trudy Campbell’s newfound team spirit was Pete’s discovery that he’d fathered a child with Peggy. I’ve done a shit job of keeping track of Pete and Peggy’s relationship in light of this revelation this season — I barely recall if they’ve been palling around like the rest of the officemates or just cordial or barely speaking to one another — but all the evidence you need for the Campbells’ current relationship can be found in their hotstepping at Roger’s party. It made me happy for both of them to see them be stars together, however briefly.

* The bit at Roger’s party where that dude asks to put his hand on Betty’s stomach? Yeesh, this really is a sexy show. The performance of desire and arousal, and the invitation to intimacy. That’s where it’s at.

* I think my idiosyncratic Mad Men crush is on Sal’s poor wife Kitty. Meow!

* On a more serious note, what do you think she knows? Even though Sal would set off a five-alarm gaydar alert for most of us today, his coworkers seem completely oblivious, so it’s reasonable to assume Kitty is or was, too. I mean, she married the guy, and apparently after nurturing a boy-next-door crush on him for years beforehand. But she obviously senses that something is off. She feels left out when Ken comes for dinner, and she tells Sal he’s been distracted or distant for months. I really find myself puzzling out her teary eyes when Sal performs the Ann-Margaret routine he’s directing in the diet soda commercial for her. At first it seems she’s emotional because he’s letting her into his world. Then it seems like she’s upset because he seems so much more passionate about this Patio ad than he is about her. Then perhaps she’s jealous of the attention this presumably young and beautiful actress is receiving from him. But…is there also a sense that in this flirty, theatrical playacting, he’s somehow more himself than he’s ever been?

* I love moments when Matthew Weiner’s Sopranos starts showing. Previously the standout was the bit with the neighbor’s pigeons, the Drapers’ dog, and Betty’s gun — the lyrical way in which that stuff was shot, the use of animals, the weird outburst of violence. This season I think there’s been more than usual. We’ve had the episode that focused on a character who was about to die as he made some portentous final memories with another character (Gene and Sally). Betty had her dream sequence during childbirth. The agency preying on the dipshit jai-alai trust-fund kid was the Scautino bustout all over again.

* And, of course, the lawnmower. That was a majestic moment, man. Hilarious and awful and unforgettable, like any number of great Sopranos moments. I know without looking that there are a million animated gifs out there of that, aren’t there? Since violence on the show is so rare, a flash of grand guignol like that probably had a similar effect on large segments of the audience to the one it had on the people there in the office. (Wait, there was a Peggy/Pete moment I remember — he caught her when she fell. Dun dun dunnnnn!) It also gave rise to some of the show’s funniest and most mordant black humor: The “He might lose the foot.” “Just when he’d gotten it in the door!” exchange was topped only by St.-John-whatsisnames grave pronouncement that “The doctors say he’ll never golf again.”

* What’s more, it gave us sympathy for Lane, for perhaps the first time. He’s seemed like a decent guy rather than a tyrant throughout, but it wasn’t until he was rewarded for his achievements at Sterling Cooper by being packed off to Bombay effective immediately, a fate he resigned himself to in the space of about 90 awkward seconds, that we realized how much his stiff upper lip, company-man persona could cost him. The owners can rely on him and thus abuse him, and making himself amenable to the abuse is the only way he can make himself indispensable. When he tells Don that he feels like Tom Sawyer at his own funeral and didn’t like the eulogy, I really felt how awful that must be: to be great at your job and respected less because of it, not more. He’s the anti-Don.

* Writing that very last sentence made me realize that I’m barely talking about Don himself! He’s receded a bit this season — perhaps because he’s not sleeping around and thus there’s less relationship drama for him to star in, while at home he takes a back seat to Betty and the baby, plus after he threw his weight around in the final confrontation with Duck over the sale, we know he’s probably got more job security than anyone else at the company?

* Still, I think we got a “shape of things to come” moment when he talks to Sally’s hot, slightly drunk teacher over the phone as she divulges her personal history, then still thinks to tell Betty that it was “no one” even as they leave for the hospital for her to give birth to their baby. The ease with which he lies is alarming.

* But so too can be the ease with which he tells the truth. I have two married siblings, as does my wife, so I’ve seen just about every possible relationship between a person and their parents-in-law, from “great” to “my God make it stop.” Even so, I was still stunned when Don told Betty “He hated me and I hated him — that’s the memory.” To put it so bluntly, to remove any wiggle room for politeness and decorum…even after Gene’s death, that’s still a huge shock to the system. Good for Sally for coming in at just the right moment and defusing the situation by apologizing for bothering the baby.

* And man, Sally’s an MVP, isn’t she? That kid’s a terrific actor, and the show really uses her without overusing her. (Lately I’ve thought about the problems faced by Game of Thrones in having so much of the story driven by children acting basically on their own. The show had to age all of its characters up for a variety of both content-based and logistical reasons, but one of them was that if they’d kept (say) Arya and Bran at their ages in the book, you’d basically be relying on children the age of Sally and Bobby Draper circa Mad Men Season Two to anchor a quarter of the show.)

* Back to the lawnmower incident: Here we had another tour de force writing performance. An entire episode is spent setting up the possibility of a new status quo, ramming it into place, and forcing both us and the characters to contemplate it…then completely undoing it with one drunken mishap. I love not being able to expect where things are going even when the show comes out and says “This is where things are going.”

* Name nerdery: One of my favorite little comics factoids involves the naming conventions at the two big superhero publishers. DC characters tend to have a first name for their last name: Clark Kent, Bruce Wayne, Hal Jordan, Barry Allen, Guy Gardner, Tim Drake, Jason Todd, Ronnie Raymond, Barry Allen. Marvel characters have alliterative names: Peter Parker, Reed Richards, Sue Storm, Stephen Strange, Matt Murdock, Bruce Banner, Scott Summers, Warren Worthington, Victor Von Doom. (Also fun: finding the exceptions. Marvel’s got Donald Blake, Bobby Drake, and Clint Barton; DC has Wally West, Guy Gardner (again) and Superman’s entire supporting cast.) I’ve noticed something similar about Mad Men. The male characters’ names are nearly always a one-syllable first name and a two-syllable surname with the emphasis on the first syllable, i.e. “First LASTname” — Don Draper, Dick Whitman, Pete Campbell, Ken Cosgrove, Bert Cooper, Paul Kinsey, Duck Phillips, Gene Hofstadt, Bill Hofstadt, The female characters’ names are nearly always a two-syllable first name and a two-syllable surname, with secondary emphasis on the first syllable of the first name and primary emphasis on the first syllable of the surname, i.e. “Firstname LASTname” — Betty Draper, Peggy Olsen, Trudy Campbell, Rachel Mencken, Mona Sterling, Sally Draper, Bobbi Barrett, Judy Hofstadt. As the alpha male and female, Roger Sterling and Joan Holloway/Harris are the exceptions that prove the rule.

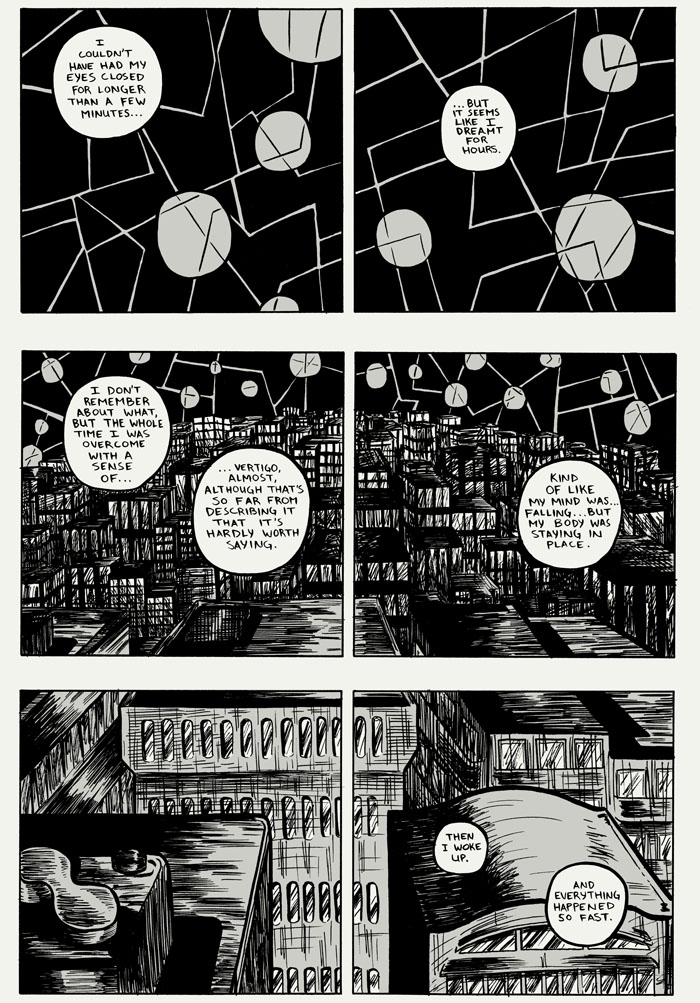

Comics Time: Sexbuzz

Sexbuzz

Andrew White, writer/artist

Self-published online, 2010-

Currently ongoing

Read it here

Holy shit. Who is this guy?

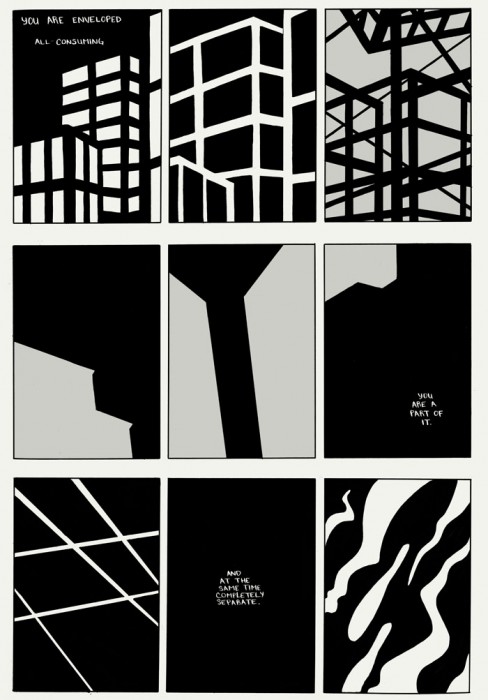

Though I first encountered Andrew White’s work through a collaboration with the writer Brian John Mitchell on one of Mitchell’s very tiny minicomics, I didn’t really become aware of White as a creator until a few weeks ago, when (I believe via twitter) I followed a link to his homepage and read this science-fiction sex/spy/slice-of-life webcomic. To say I was impressed would be an absurd understatement. Let me put it this way: I emailed my friends freaking out about him, but refused to tell him his name, because I didn’t want the word going out. A quick google search, in fact, had revealed essentially zero hits. The only person talking about Andrew White was Andrew White, and barely at that. That is nuts.

In Sexbuzz, you’ll see a lot of what you like in the comics of Dash Shaw in the way White fuses science-fictional ideas with formal play rather than with set dressing, which in turn gives him the freedom to pursue human-interest storylines without getting tripped up by excessive visual worldbuilding. You’ll see some Ryan Cecil Smith in how he uses loose, almost ramshackle character designs and a fine sense of movement and momentum in his action sequences to make his world feel loose, large, and full of possibility. You’ll see Paul Pope in his big thick ink squiggles, and a fixation on the role of physical objects as a loci of near-future science fiction rather than a more ethereal digital conception of the genre. You’ll even see some Gilbert Hernandez in the way he occasionally pulls back for isolated, abstracted images of the world around us that suffuses it with a weird melancholy magic.

But beyond all the trainspotting, White’s just very good at making the most of the tools at his disposal. The comic’s long vertical scroll gives you the sense of a long story, a story to get lost in, unfurling before your eyes. His graytones are beautifully applied for shading and contour, but also enhance the impression that this is a dingy, rain-soaked city of the night. He’ll slow time down to a crawl with spread-apart panels that evoke McCloud’s infinite canvas without using it outright, then leap forward in time at a chapter break. And he’s constructed the story itself — about underemployed twentysomethings who steal the works for their dangerous technological sex drug Sexbuzz from a sinister corporation — with ample room to play in any number of genres: sci-fi spy thriller, a satire of the corporate/security state, alt/lit young-person relationship drama, action, romance, even erotica. (The nakedly transactional exhibitionism of that opening chapter is hot stuff.) Like Jesse Moynihan’s Forming before it, it’s the kind of webcomic you dream of stumbling across. Long may it run.

(Here are a few pages.)

Carnival of souls: Special “post-NYCC” edition

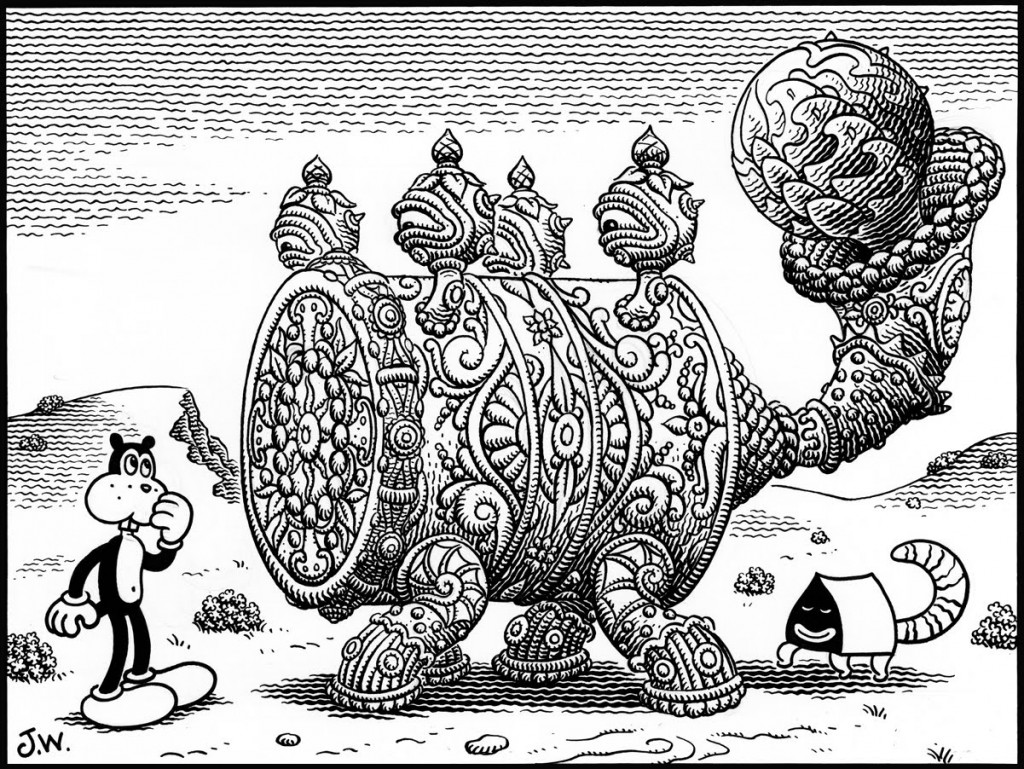

* Recently on Robot 6: Everybody’s talking about “The Love Bunglers,” and everybody should be talking about Jim Woodring too.

* Dustin Harbin salutes Dylan Williams.

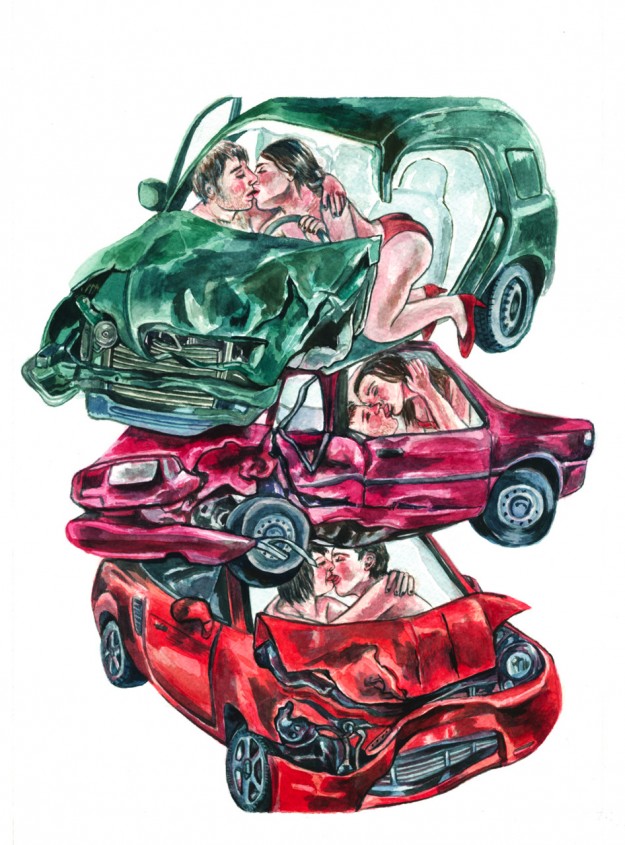

* Lisa Hanawalt draws J.G. Ballard and opens a spiffy new store.

* New comics from Jonny Negron! Not, perhaps, what you’d expect.

* Jordan Crane’s Keeping Two has taken a turn.

* Grant Morrison’s long-discussed plans for a Wonder Woman series seem to be taking shape for sometime next year. Sounds kinky. I wonder if anyone will mutilate a horse, walk around a room naked, or dismember a guy in this one.

* David B. is working on a book on the history of U.S./Middle East relations?

* DC’s relaunch moved a lot of units. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I think this is the first time a Big Two publisher has ever brought forth its own set of actual sales figures since I’ve been following these things.

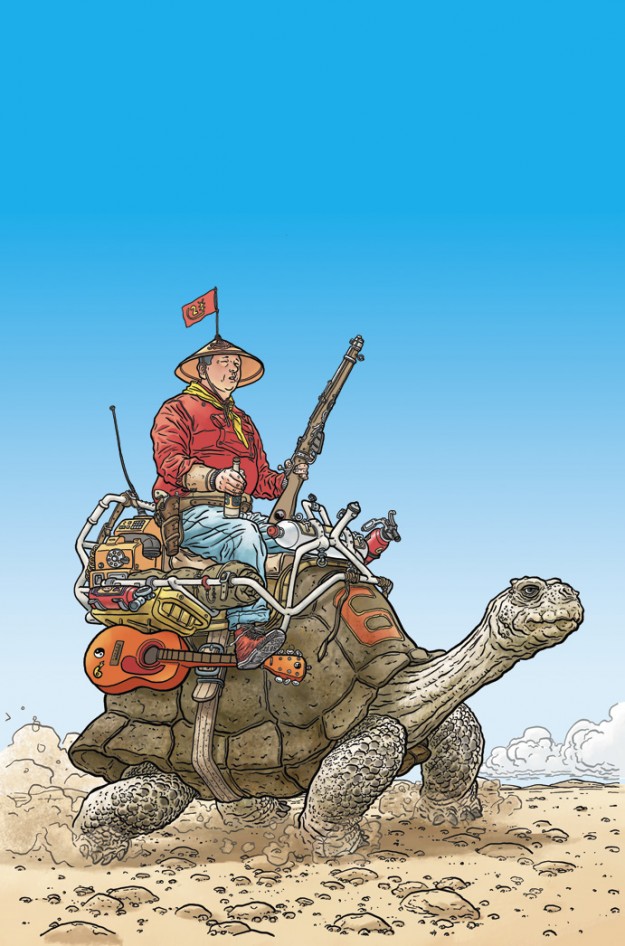

* Geof Darrow’s Shaolin Cowboy never seemed to find its way into Wizard’s hallowed halls when I worked there during its run, so I have yet to read any of it. I can’t tell if the NYCC announcement that the title’s moving to Dark Horse means they’ll also be reprinting the previous material in addition to the three new issues they’ve got planned. I hope it does. There couldn’t be a more influential artist than Darrow right now.

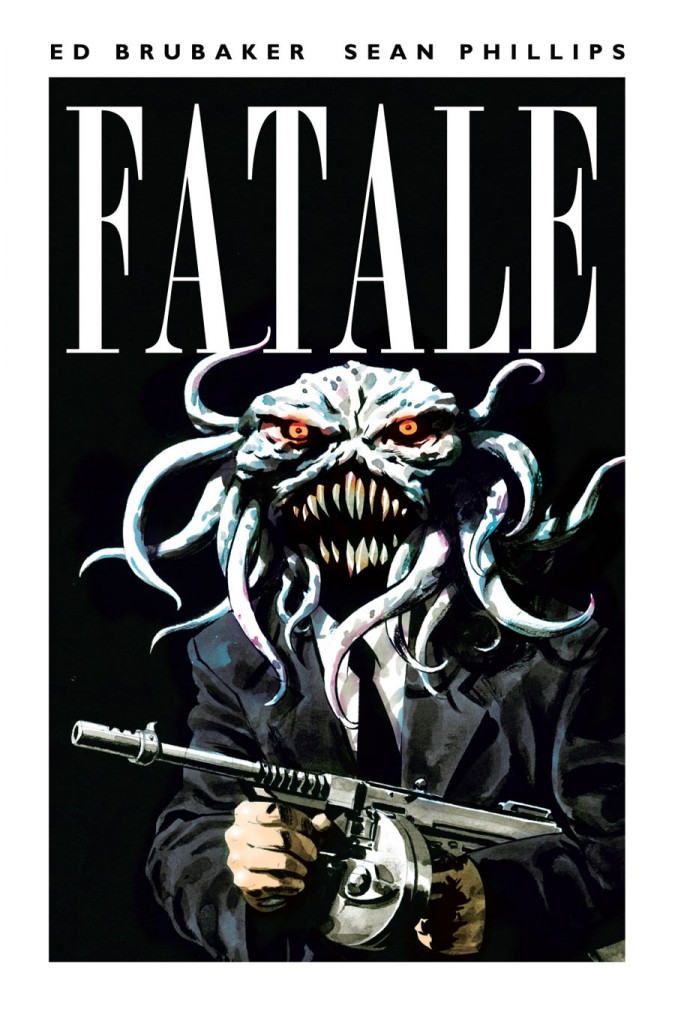

* The Sleeper/Criminal/Incognito team of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips are working on a Lovecraftian noir series called Fatale, surprisingly for Image rather than Marvel’s creator-owned Icon line.

* At Marvel proper, Rick Remender and Gabriel Hardman, one of their best writers and best artists respectively, will be taking over Secret Avengers. It’ll probably be pretty darn good. I read somewhere that Bettie Breitweiser, one of their best colorists, won’t be rejoining Hardman here, though, which is too bad. Also Jack Kirby deserved more credit and rights and money and so do his heirs, but you knew that.

* Marvel’s Tom Brevoort explains how nearly all of a given superhero franchise’s titles can end up dumped into stores on the same day. I do wonder how DC’s experiment with rigorous scheduling will affect this conventional wisdom.

* Worth noting: Zak Smith/Sabbath wrote an RPG manual for his fantasy city Vornheim.

* Real Life Horror: Wake me when Obama sends military advisors to take down the pope.

* They’re not making movie cameras anymore. My jaw dropped when I read this.

* Roger Corman, ladies and gentlemen.

* Scarlet Witch cosplayer at NYCC photographed by Judy Stephens. Sure, sure.

Comics Time: Thickness #2

Thickness #2

Angie Wang, Lisa Hanawalt, Michael DeForge, Mickey Zacchilli, Brandon Graham, True Chubbo, Jillian Tamaki, writers/artists

Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge, editors

self-published, October 2011

60 pages

$12

Buy it from the Thickness website

Anthology of the year? I’d need to double-check some release dates, but it certainly seems that way to me. The second installment of Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge’s art-smut comics series is an intense, diverse collection of sex comics, beautifully printed and rich enough to revisit well after your first virgin read.

Michael DeForge, god help us all, continues his juggernaut run with what could well be his best comic yet. “College Girl by Night” stars a young man who’s transformed by the light of the full moon into a beautiful young woman, and uses the time to seduce and fuck college boys. His/her narrative captions don’t comment on the night-in-the-life activities depicted in the art, but rather explain the background of the transformations, her preferred conquests (tired of her “spoiled, drunken nineteen-year-olds,” she’s “made vague plans to set my sights on Edgeton professors, posing a student seeking advice after hours”), her almost idle questions about the science of it all (“Maybe if I got pregnant, it would only show when I transformed. If I even have a uterus, that is”), fictional precedents (“When Billy changed into Captain Marvel he wasn’t technically ‘transforming’…he was having his Billy Batson body physically replaced with an entirely different Captain Marvel one”), and daydreams about starting a relationship while in female form (“I once found a Missed Connection written about me on Craigslist”). It’s funny stuff, featuring DeForge’s trademark juxtaposition of the fantastic and the mundane. But it’s also really, really hot stuff. His character design for the main character’s female form is a note-perfect assemblage of alluring details: spagetti-like tendrils of hair, a dusting of freckles, a short and nearly translucent dress, long lashes that flutter when she throws her mouth open in ecstasy. But then DeForge takes the ruthlessly (if ironically) heterosexual nature of the situation (as she herself puts it, “Is it hugely unimaginative that during my time as a woman, the only activities I’ve done so far is fuck myself or get fucked?”) and crashes it right into its own subtext, reversing the transformation mid-coitus and presenting the two college guys now present on the scene with the opportunity to pick up where they left off, or not. Even if your door doesn’t swing in that direction, there’s a willingness to be led solely by pleasure and desire, a “Shhhh–no one can see, so why not?” quality, that’s hard to deny.

Brandon Graham’s “Dirty Deeds” is the most lighthearted of the contributions (well, aside from True Chubbo’s), and his sense of humor isn’t mine. It’s got this bigfooted vaudevillian underground schtickiness to it that’s just not my thing unless it’s Marc Bell. (Lots and lots of puns: “prostate of shock,” “cervix with a smile,” “I was young, I needed the monkey” — that last one’s a bit of a long story.) But that’s not to say that a breezy sex romp isn’t a welcome addition to this issue’s 31 flavors. Certainly Graham’s warm, curving line is shiny and happy enough to make up for a few jokes that leave me cold, and it’s fascinating watching him use it to achieve certain unique effects — the way he crams detail into limited segments of the page, piling line on line like a soft-serve ice cream cone, while letting the rest of the page breathe, say, which in turn lets him work wonders with images of massive science-fictional scale. And he really makes the most of Sands’s red-orange risograph’d coloring, particularly with his vivacious heroine’s hair and a sexy tan-line effect using what looks like the world’s tiniest zipatone dots. I’m kind of amazed that anything would give this Adrian Tomine print a run for its money in the “Sexiest Use of Tanlines 2011” sweepstakes, but there you have it.

Mickey Zacchilli’s contribution is the most off-model of the bunch, a melancholy affair in which a Brian Chippendalesque lost girl loses her wedding ring and therefore enters some weird subterranean sex chamber, in which a brawny beast and a “slime worm” have their way with her as she worries about other things. What keeps her going is the promise of ice cream on the other side of the chamber, but the showstopping reverie begins with the phrase “All I could think about at that moment were all the various objects that I had never stuck in my vagina.” Arrayed in the closest thing to a clinical grid as Zacchilli’s noisy, scratchy line can muster, this assortment goes from “Yeah, okay, feasible for a curious young woman” (“screwdriver,” “chisel tip Sharpie permanent marker”) to “uh-oh” (“rawhide dog bone,” “rotting arm,” “disembodied head”). When added to the brusque treatment she receives from the creature who lets her in — “Thru the door Alice, Jeanette, Angie, whatever” he says, her identity unimportant — and her tears when she discovers the ice cream shop is closed, it makes for a distressing portrait of disconnect between mind and body, thought and deed.

Dare I call Angie Wang’s contribution erotica rather than smut? Wang offers a four-page start-to-finish portrait of two women — one seemingly shy or hesitant, the other taking charge — having sex. Each panel depicts a discrete body part or moment of connection. It’s a familiar panoptic effect for this kind of thing, and I usually find it to be a bit false to the experience of sex, presenting it as a sort of greatest-hits grab bag rather than a journey from start to finish where the momentum, the upping of the ante from moment to moment, is key. But Wang cleverly jettisons the mishmash approach with an array of techniques: ratcheting the panel grid back from page to page, from 16 to 9 to 4 to a final, climactic (pun intended) splash page; using tangents to connect one panel to the next; paring away dialogue and sound as she goes; altering the focus of each page, from foreplay to initial genital contact to climax to afterglow. Whether despite or because of its delicate, painterly line, it’s got oomph.

Lisa Hanawalt’s contribution is profoundly Hanawaltian. Using the tried-and-true porn setup of the teacher with the hot student, she subverts (or heightens, depending on what you’re into) the fantasy by having the pair’s taboo rendez-vous take place in full view of the rest of the class; the teacher doesn’t even stop delivering his lesson on unreliable narrators (“the narrator makes mistakes” he says as he unzips his fly). Hanawalt apes the male focus on individual body parts with alarming accuracy: “Oh god, her tits! Tiiiiiits…And that ASS,” thinks the teacher over a series of panels focusing on the student’s curves with that familiar combination of thumbs-up celebration and lizard-brain leer. Oh, did I mention she short-circuits the whole thing by giving the girl the featureless conical head of a worm while stuffing her cleavage with fibrous miniature worms, and by giving the bird-headed teacher a penis that itself ends in a bird’s head, which literally vomits its semen all over her ass and vagina when he pulls out? When she slaps a David Lee Roth-referencing “CLASS DISMISSED!” on the final panel, I’m not sure whether to run for the door or stay for extra credit.

The final two contributions hearken back to Sands’s zine roots: Ray Sohn and his anonymous wife serve up one of the funniest, grossest True Chubbo strips to date (you’ll love the Lawrence of Arabia “NO PRISONERS!” quote, especially once you see the context in which it’s being quoted), while Jillian Tamaki’s centerfold pinup intrigues with its incongruous details — a monumental topless woman kneels amid lush flowers and a small army of Russian doll-like people-shaped dildos (I think?), her implacable gaze juxtaposed with her very human bikini-area stubble and a big goofy digital watch on her wrist. They give Thickness #2 a welcome diversity of form as well as content, a “hey, here’s everything that was fit to print” feel.

Thickness #2 is the real deal: talented, fearless cartoonists working in that viscous red zone of pleasure, terror, filth, and fun where the only thing that matters is what the body does and doesn’t want, and your brain is simply forced to go along for the ride. Bravo, thumbs up, panties down.

Quick Walking Dead poll

Is anyone planning to watch the Season Two premiere of The Walking Dead? I’m not, on “life’s too short” grounds. That first season was pretty bad, and there are many, many better and/or more enjoyable shows I can be watching. I’m just curious what y’all have decided. Let me know in the comments if you like.

New York Comic Con report

I stopped by NYCC on Friday evening. Here’s what I saw.

* The on-site press pass situation is hilarious. Anyone could walk in off the street and grab one if they knew where to look. While I was getting mine, I watched some loudmouth gamer basically annoy a staffer into giving him one for his buddy despite both he and she acknowledging that the buddy was not press. (He walked away saying “Thank you, sweetheart,” like he was Roger Sterling.) All I needed to get mine was the outdated business card I paid $10 for on the internet. “Do you need to see my credentials?” I asked. “Um, okay, if you have ’em,” was the reply. When I actually took them out, she waved them away.

* Best cosplay: Solomon Grundy on built-in stilts. Runner-up: Ms. Marvel With Her Ass Hanging Out. As one commentator put it, “She looks like a Mike Deodato drawing, but in this case it’s okay, because she has agency.”

* From a look at their table, I’m pretty sure the Suicide Girls were 14 years old.

* Some people smelled bad. The rain on Friday did not improve the aroma. I don’t go in for the smelly-nerd stereotype, but for what it’s worth, I pass through Penn Station twice a day every day and don’t encounter the Pigpen-like clouds of stink, so it’s not just a phenomenon of crowds, I don’t suppose.

* I walked past an enormous cosplay group photo session for some anime I didn’t recognize at all. Nerddom is bigger than ever and there are worlds within worlds, man, worlds within worlds.

* The picture of comics presented at this thing makes San Diego look like the Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival. I wonder if the show could make a go of building up an alternative or literary comics presence if they put their mind to it. I sort of doubt it. As a NYC metro-area commuter show, it’s competing for those readers with more targeted area cons like BCGF, MoCCA, and even KingCon. For those traveling longer distances, including some of the bigger publishers, the larger East Coast also offers SPX and TCAF. It’s great to see Top Shelf and NBM tabling next to each other, but you’d need Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly at the very least to approach some kind of altcomix critical mass, plus a dedicated programming slate, and no one involved appears to have much interest in that. This is one situation where I think Tom Spurgeon’s frequent suggestion of independent counterprogramming that cross-honors passes from the main event might make a lot of sense, but you’d be fighting for PR oxygen against a show that’s damn near San Diego in size without people’s ingrained inclination to go to San Diego no matter what.

* I spent about two hours walking the floor. I could have spent a lot more than that, hours permitting, I’m sure, because I do enjoy the sheer spectacle of it all. That’s just one of those things you either like or don’t, like how for some people Guinness is too heavy to drink and for others you can knock down pint after pint. But the spectacle is the extent of what it offers, to me at least. The flea market of back issues, original art, t-shirts, toys, and tchotchkes; the big booths hawking video games or wrestling or cartoons or whatever with loudspeakers and music and women in tight clothes; long lines of readers excited to meet Marvel and DC creators; cosplay, cosplay, and more cosplay; Nerd Nation at its best and worst, from happy teen couples to middle-aged men loudly complaining about Ryan Reynolds’s CGI Green Lantern costume and everything in between. I left at closing, knowing I wasn’t missing much by not going back again the rest of the weekend, but also knowing I could probably quite happily spend days and days in there.

* If you like talented superhero/genre artists, then Artists Alley was pretty terrific, if you ask me. I met Chris Burnham and walked past David Lloyd and Geof Darrow, just for example. There were definitely dozens of people hawking sad-looking self-published indy superbooks, but there were also some real talents in there.

* I went to a wonderful party on Friday night thrown by some of the younger Wizard alums that encompassed representatives of Marvel, Dark Horse, CBR, ComicsAlliance, The Comics Journal, Hasbro, Diamond Select, and MTV; scheduling conflicts were all that kept DC, Archaia, Archie, and Newsarama from having staff there as well. We’ve done alright! There and elsewhere, I met for the first time people I’ve talked to online for literally years. For the first time I met Sean Mackiewicz, who had been my source for dozens of DC freelance assignments over the course of two or three years, and Steve Wacker, who’s my editor on the Spider-Man comic I wrote that comes out in a couple weeks. Twice I bumped into my old boss Pat McCallum, who now works at DC but whom I hadn’t seen in years, possibly since the day he left Wizard. Moreover, I think this is what I like best about NYCC: It brings people I know and love in the industry together in Manhattan. It’s a rare case where I really do prefer the socializing surrounding the event to the event itself.

Long Mad Men thoughts

I believe I am two episodes into Season Three. SPOILER WARNING.

* The key to Don Draper is war. I’ve thought this ever since the pilot episode, before I knew…anything about him, really. There’s a moment in that first hour where he takes a nap in his office, and slowly the sounds of explosions begin echoing in his head. I believe at some point before that we caught a glimpse of his Purple Heart, but that sound cue (effectively cribbed a few years later by Game of Thrones) was the moment when I realized that something happened to him out there, wherever there was. Everything we’ve seen since lends further credence to this notion. Dick Whitman became Don Draper in an explosion in Korea. The prospect of “total annihilation” sends him running from an aerospace conference directly into a lost fortnight of the soul. And I think it’s his candor about the Cuban Missile Crisis making him “sick” in his letter of apology to Betty that precipitates their subsequent reunion as much as anything else. I don’t think I’ve wrestled with this enough to boil down what Don’s experiences in Korea did to him and mean to him to a single sentence, but I promise you it’s not for lack of trying. But I do believe that the hole in Don, the part of Don that’s so hard to define — that hole was created by being blown open.

* My recent experiences with miscarriages, pregnancy complications, premature childbirth, and fatherhood have humbled me by showing me just how beholden to biography criticism really is. Man oh man, am I ever a mark for neglected-baby shit now. Every glass of booze or Lucky Strike that goes into the mouth of one of the pregnant characters is like nails on my mental chalkboard, and when Peggy rejected her baby that first night, or when Betty left the gynecologist’s office without a checkup and then proceeded to do various things he’d instructed her not to do anymore, I had a tough time getting around that with them. The funny thing is that, like my wife, I’m more pro-choice after our ordeal than I ever was before it. I think it’s the noncommittal quality of Peggy and Betty’s ways of dealing with their unwanted pregnancies that bothered me. If Betty had gone to that “doctor in Albany” that Francine told her about rather than simply going horseback riding again like it ain’t no thing, I’d have been much more okay with it and with her. Make a decision, is what I’m saying. I dunno, this shit’s complicated.

* Duck Phillips’s self-immolation was the show at its meanest. The guy’s only crime, it seems, was just not quite playing the game right. Everybody else gets to be a drunk — he has to be an alcoholic. Everyone else cheats — he gets a divorce, and doesn’t even have a 20-year-old secretary to show for it. Everyone else thinks big and takes risks — his big thoughts and risks never seem to pan out. When he finally shoots for the moon, he’s not Neil Armstrong, he’s Gordo the ill-fated space monkey. Sure, I was rooting for Don, and was invested enough in Duck’s defeat to literally shout “He doesn’t have a contract, you dope!” at my laptop screen out loud on the train, alarming the woman in the seat next to me. But even so, watching his seemingly successful office coup and business masterstroke end with his former boss dismissing him by saying “He could never hold his liquor” was a gutpunch. And like that, poof, he’s gone.

* That whole storyline was another terrific case of misdirection by the writers, of course. The entire time Don was wandering around California incommunicado, I anticipated a total meltdown or freakout when he returned to find Sterling Cooper sold out from under him and Duck Phillips calling the shots. Instead he collected his half million dollars, blithely offered to quit, and destroyed Duck’s career with seven syllables: “I don’t have a contract.” It was like one of his “magic pitches” (I wish I remember who introduced that phrase to me), where he has just the right idea at just the right time. He didn’t even break a sweat. He’s a miracle man.

* Betty’s post-adultery rapprochement with Don was one of the show’s few too-predictable moments. They’d been building up to it for so long that I had no doubt Betty would cheat one time only, “getting it out of her system,” in order to welcome Don back to the family. In general I find the supposed epiphanic value of sex to unhappy suburban women overvalued in fiction, as if there’s a whole nation of Joan Allen in Pleasantville out there just one bathtub frig away from Freedom. Still, it could be worse: They could have made like the odious American Beauty and made the housewife’s sexual satisfaction an object of ridicule and contempt. Personally, if you’re gonna go the whole When Hausfraus Fuck route, I prefer the Hellraiser option.

* Less predictable, and much more troubling for that, was the fallout for Joan’s rape by her fiancé. Specifically, there wasn’t any. I expected the Holloway facade to finally crack, but this was no life-altering trauma for her, because this is par for the course. If marital rape (I know they weren’t married yet, but I don’t know an adjectival form for fiancé) still occasionally has a hard time mustering outrage today, imagine what it would have been like then. Like smoking while pregnant or after a pair of heart attacks, perhaps for some people it’s something you don’t even know is bad. It was the show’s most depressing depiction of the era’s misogyny this side of all those avuncular or leering male doctors dispensing unsolicited life advice with each exam. Their lives are not their own.

* People told me Alison Brie’s Trudy Campbell would improve, and lo and behold. She and Pete are so different together, so much more understanding of and genuinely interested in one another’s feelings and opinions, in that first episode of Season Three that it almost feels like a continuity error. But I guess that if you peg it to Pete’s falling out with Trudy’s father and his own mother, you’ve got the precipitating incidents you need.

* Speaking of potentially jarring character transitions, I was a bit surprised to see Don back up to his old poon-hound tricks again with that stewardess in Baltimore before the Season Three premiere was even over. I figured we’d at least see him make an effort to stay faithful to Betty before failing. And yet this felt much less like plothammering to me than…well, I can’t say, but another acclaimed drama of recent years featured a womanizing, hard-drinking leading man who briefly reformed only to lapse back into bastardry when the demands of the writers required it. There — perhaps because the original development felt so well-earned — the reversal felt cheap and trollish. Here it’s another clue in the mystery of Don Draper.

* What makes it all the more puzzling is that both Don’s apology and his subsequent lapse were juxtaposed against two of the clearest indicators that he could well pass the Good Guy test. Don came home to Betty after we learn that he’s friends, close friends, platonic friends, with the woman whose dead husband’s identity he stole. For that kind of genuine, easy affection to develop under that kind of hideous circumstance, Dick Whitman must be some hell of a guy, right? And after he cheats, he discovers that Sal is gay, but subtly makes it clear to him that he has no intention of either outing nor ostracizing him for it. It’s not just that Don’s displaying admirable tolerance for a man of his era, although that’s awesome. It’s that he’s not a hypocrite. He knows how important keeping a secret and playing a part can be, so he doesn’t hold it against Sal. That’s admirable, in its way. (He’s been hard on Betty for being too sexy for others’ enjoyment from time to time — flirting with Roger at dinner, wearing a bikini to the pool — but while I can’t imagine him reacting well to her actual cheating, I feel like these bother him as breaches of decorum rather than as acts of mote/beam optometry.)

* Don to Peggy: “You’re not an artist, you solve problems.” Copywriters, this is our gift. This is our curse.

* Peggy Olson’s A Series of Unfortunate Hairstyles

* No, semi-seriously: Elisabeth Moss is an attractive lady, but in Peggy it’s tough to see. I had a real holy-shit moment recently when I realized that the girl in that uncomfortably intimate Excedrin Migraine commercial that had driven my wife and I crazy for years during Judge Judy was none other than Sterling Cooper’s newest copywriter because the voice and the eyes were virtually the only thing recognizable about her. That commercial is predicated, more or less, on the appeal of being close enough to this dewy-eyed, breathy-voiced young lady to make out with her, whereas Peggy, to me, has been defined by the awkward middle part of her bangs. Even her makeover at the hands of Bob Dylan enthusiast and noted pervert Curt Smith didn’t fix it. Only when she took a swing at reenacting Ann-Margaret’s Bye Bye Birdie performance in the mirror at home was I reminded that hey, my goodness.

* Sterling silver-tongued.

* Another gasp-out-loud-on-the-train moment: The save-the-date for Roger’s daughter’s wedding. The missile crisis material was so effective — it was the first time the show really affected my personality throughout the day, making me nervous and paranoid — that I was looking forward to seeing how they’d deal with Kennedy’s assassination despite its potentially hackneyed nature. Turns out they’re gonna run right into it full speed. This should be interesting.

* Don got to where he is — at the top of his profession, basically untouchable even by the new owners — because everyone respects his creative talent. Creative talent could make you in that world. I don’t give a fuck about fedoras and suits, but that’s something worth getting nostalgic over.

* Is it time to start shipping Don and Peggy? Deggy?

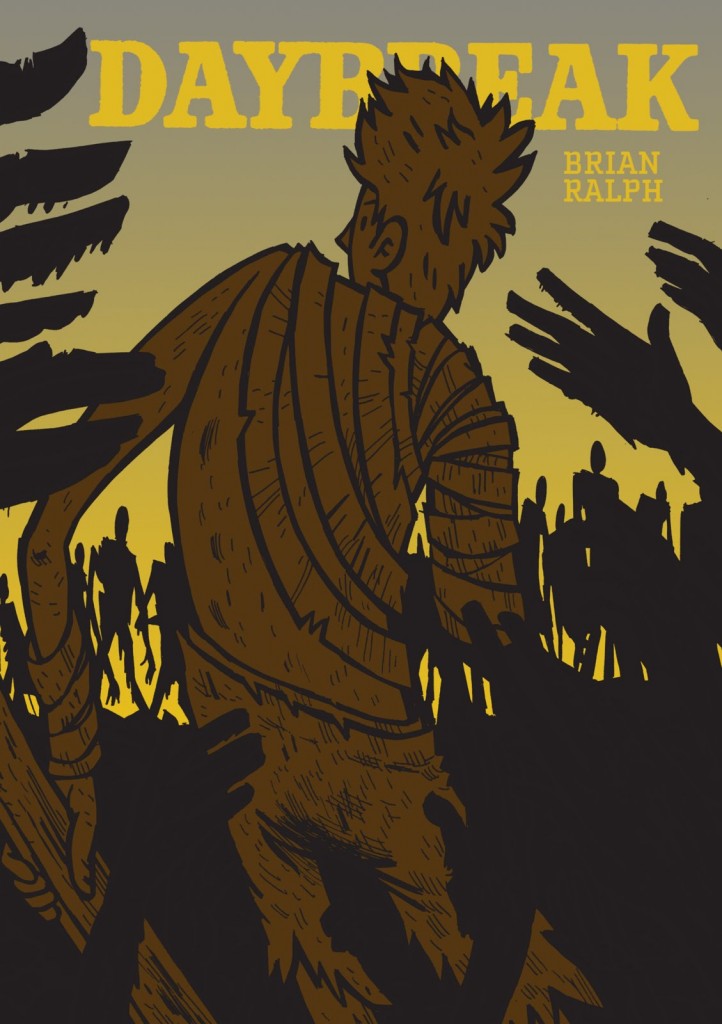

Comics Time: Daybreak

Daybreak

Brian Ralph, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, 2011

160 pages, hardcover

$21.95

Buy it from Drawn & Quarterly

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Carnival of souls: Sparkplug, Netflix, Partyka at the Whitney, more

* Sparkplug Comic Books will continue, under the watch of Dylan Williams’s wife Emily Nilsson, his friend Tom Neely, and his colleague Virginia Paine. They haven’t decided whether or when they’ll be able to start publishing new work, though they’d like to, but they’re continuing to sell and promote the company’s existing, excellent line-up.

* Amazingly, Netflix has backed down off its previously announced plan to divert its DVD subscribers into a separate service with the absurd name Qwikster. I look forward to reading retractions from the folks who wrote that that was secretly a brilliant maneuver. As I said at the time, regardless of the underlying thought process, repeatedly and publicly antagonizing your customers with sweeping business-model changes that make your services more inconvenient and more expensive, delivered first with no real explanation and then with an “apology” that amounted to “sorry for doing that horrible thing, now here’s something even worse, something so bad that I, the CEO of the company doing it, seem on the verge of tears about it” is — surprise! — a bad business move. It was the strangest thing I’d ever seen a popular consumer company do, and now it’s doubly so.

* My chums in the Partyka collective will be part of the Desert Island Comic Zine Party for kids at the Whitney Museum this Saturday afternoon. Sounds like a good time for the little ones.

* Recently on Robot 6:

* Interesting insights into Ghost World and Shortcomings may be found in this Daniel Clowes/Adrian Tomine panel report.

* Bob Temuka’s post on the Jaime Hernandez/Locas material in Love and Rockets: New Stories #4 is appropriately emotional and dead-on. I talk a bit about it here.

* The revived Wow Cool publishing/mail-order outfit is impressive.

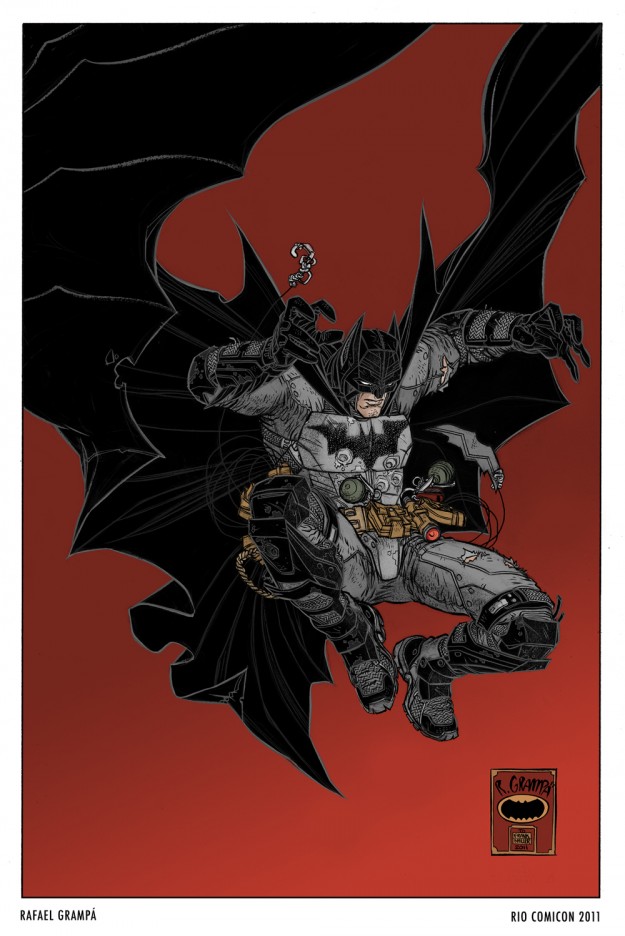

* Here’s a very pretty picture of Batman by Rafael Grampá.

* Via everyone: Liquid Television is now online in its entirety, along with related weird animated programs and station IDs from the MTV vaults. That was a real atom bomb of alt-culture for people of a certain age, one that if I’m not mistaken slightly predated Nirvana’s opening of the floodgates for that sort of material and was therefore even more of a cultural category error when in arrived on our teevees between Janet Jackson videos.

* Tom Spurgeon’s nine thoughts on the DC relaunch’s success. Of the batch, I was struck by point six — DC’s newfound insistence on regular shipping will require fill-in slots that should provide better opportunities for new or new-to-the-company creators than the usual miniseries and tryout books — and point nine — the unpleasant-to-much-of-the-online-fan-press tone of many of these successful books will force a generation of journalists weaned on the we’re-all-in-this-together spirit of comics return to cultural prominence in the ’00s to reexamine those assumptions.

* It’s spoilery so I’m staying away (even though it says it’s not spoilery, the first thing they talk about was spoilery as fuck), but Clive Barker talks to his official site Revelations about the recently released Abarat: Absolute Midnight, the third book in his lushly illustrated YA fantasy series. I recommend you read the intro, however, as it details what seems like a hellish last few years for Barker in his personal life — surgery, divorce, death. He’s one of the friendliest people I’ve ever met in this business, hugely generous in spirit, so every time I hear about these things I feel just awful for him. Still, you have to figure that if anyone’s capable of channeling real life awfulness into his art, it’s Clive Barker.

* Box Brown’s Retrofit Comics is up to its second old-school alternative-comic-book-format release, Colleen Frakes and Betsy Swardlick’s Drag Bandits. To paraphrase Barton Fink, I got a feeling we’ll be hearing from that Colleen Frakes, and I don’t mean a postcard.

* What’s Closed Caption Comics member Mollie Goldstrom been up to?

* It bears repeating that Tales Designed to Thrizzle #7 is on the way.

* It also bears repeating that Jim Woodring is posting things like this five, six days a week lately.

* Hellen Jo draws girls masturbating for Vice. These are illustrations for an article on the topic that is the Vice-iest Vice article ever to Vice, so be warned, but still, it’s Hellen Jo drawing girls masturbating. (Via Same Hat!)

* I have no brief whatsoever with “the Milkyway films of Johnnie To Kei-fung,” but this David Bordwell piece on To’s work begins with an explanation of his elliptical storytelling method that should be of great interest to Jaime Hernandez fans.

* Would you like to watch Synth Britannia, the synthpop-focused edition of BBC4’s wonderful series of rock docs, on YouTube in its entirety? Of course you would. (Via Matt Maxwell.)

Two brief Mad Men thoughts

IT OCCURS TO ME I SHOULD BE SPOILER TAGGING THESE

* I just finished the Matthew Weiner-scripted episode toward the back end of Season Two in which Don Draper has his Los Angeles idyl with the idle rich Eurotrash and their aptly/portentously/heavyhandedly-named scion Joy. While Don’s out there fiddling and relearning not to say no to things he wants (Joy, you are setting a bad example), Rome’s burning in the form of Duck Phillips’s attempt to cement his position, and take over Creative, by having his old British company buy out Sterling Cooper. What I love about this development is probably just long-form fiction writing 101, but here it is:

At the end of Season One, Don was faced with a choice. He could hire an outside applicant to take over his old position as he moved up to partner, with Duck the leading candidate, or he could promote Pete Campbell. Neither Don nor we in the audience wanted him to do the latter, for a number of reasons: 1) Pete was too big for his britches and didn’t seem to deserve the promotion on a professional level; 2) Pete was generally an obnoxious creep even by Sterling Coo standards and rewarding that behavior would have been unpleasant to watch; 3) Most directly, Pete attempted to secure the position through blackmail, and both on a “Crime Does Not Pay” level and in the sense that Don is a more likeable character than Pete, we wanted to see that fail. So Don hires Duck, then ends Pete’s game of chicken by deliberately crashing into him, and finally emerges victorious and more secure than ever. Hooray! In the moment, it looked like he made the right move.

And in the moment, he probably did make the right move! Promoting Pete under those circumstances would have been disastrous for Don, and probably not so hot for the company either. (Or for Pete, I suspect.) But this outcome — which Don selected and fought for, taking a risk and reaping the reward — had the unintended consequence of completely undermining his own happiness and power at the job. (At least I think it will — I haven’t seen how the deal with the Brits turns out yet, as I’m no further than the episode where it was first brought up.) What a great technique for the writers to use: They gave their character what he wanted, but instead of either a happy ending or a pat “be careful what you wish for” as a result, they use it as the seed from which something he absolutely doesn’t want will eventually grow. The Don vs. Duck line emerges not as a direct continuation of the Don vs. Pete line, but off on a tangent we couldn’t have predicted, and one we couldn’t have followed if Don and Pete hadn’t been made to collide in the first place. It’s Curt Purcell’s idea of narrative shrapnel (warning: A Song of Ice and Fire spoilers at the link) writ large. And it’s a great way for writers of serialized fiction to keep their stories going when seeming endpoints are reached.

* As if a film studies major couldn’t have enough fun making hay out of the name “Don Draper,” they went and made his real name “Dick Whitman.” Drop a “D” from the former and add an “e” to the latter and you’ve got an A in the class.