Archive for the ‘Pain Don’t Hurt’ Category

099. The Phantom Menace

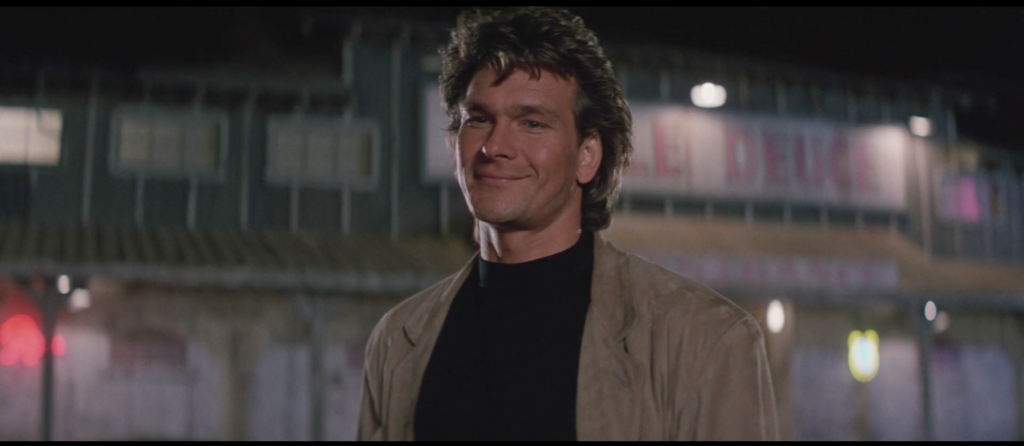

April 9, 2019WESLEY: This is my town. Don’t you forget it.

DALTON: So what does he take?

RED: Who?

DALTON: Brad WesIey.

RED: Ten percent…to start. Oh, it’s all legal-like. He formed the Jasper Improvement Society. All the businesses in town belong to it.

DALTON: You’ve gotten rich off the people in this town.

WESLEY: You bet your ass I have. And I’m gonna get richer. I believe we all have a purpose on this earth. A destiny. I have a faith in that destiny. It tells me to gather unto me what is mine.

RED: Twenty years I’ve watched Wesley get richer while everybody else around him got poorer.

TILGHMAN: Anyway, I’ve come into a little bit of money.

TILGHMAN: This is our town. And don’t you forget it.

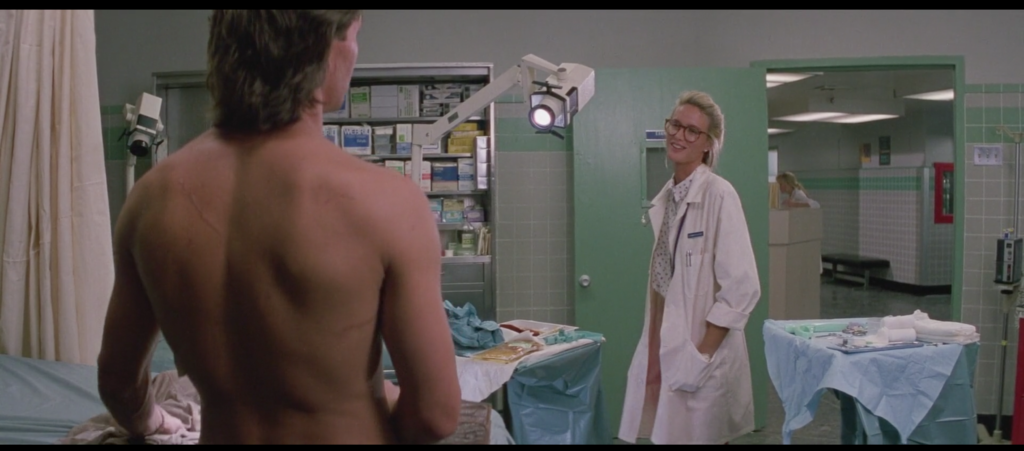

100. Pain don’t hurt

April 10, 2019Look, all he’s saying is that it doesn’t bother him that much. Why would you doubt him? You’ve just read his life story in the form of a medical file. Thirty-one broken bones, two bullet wounds, nine puncture wounds, and four stainless steel screws. To these you are about to add nine staples, to close the knife wound he incurred in the process of physically fighting multiple armed attackers in his employer’s office. He’s a bouncer by trade, and taking it is as much a part of the job as dishing it out. More so, perhaps. The fight has to come to him, not the other way around. Until someone’s ready and willing and able to hurt him he’s off duty. So he turned down the anesthetic, so what. Pain is how he clocks in.

But there’s more to it than that, you suspect. Because the non-standard subject-verb agreement is…it’s cute, you guess, but you know he knows better. In that job, with that body—you’ll afford him the working-class hero affectation, but that’s what it is. Again, you’ve read his medical file. You know he went to NYU. You know he keeps this information in his medical file, for some reason. You suspect, in the minute you’ve known him you suspect, that he’s put real thought into the things he says, for better or…

Beautiful eyes. Blue. He has a blue-eyed smile, too, you think, unsure what that means, sure that it’s right.

You’ve been with violent men before. There, now you’ve thought it, now it’s out in the open. Not with you, never with you, not really, no not really, though you’ve heard things since then that you have a hard time believing yet also believe the moment you hear them. What’s that girl’s name? The blonde woman. She was with one of his boys, and you were with him, and you left town, and he went nuts, and now she’s with him and the boys have moved on, you suppose. Not with you, though, not really.

But Brad didn’t need to hit you to hurt you. His charisma, his worldliness, his ease with success, the way he promised you everything and meant it: When you saw it for what it was—for its casual cruelty and gross acquisitiveness and lack of empathy and small-minded understanding of what “everything” even means—and the life you’d planned to last forever kindled and burned and crumbled to ash in the light of it, oh, he hurt you then. He hurt you so badly you ran to get away from it, like the feelings lived in that godawful mansion and you could leave them there mounted on the wall, immobile, unable to reach you again.

Has he ever been hurt, you wonder? Hurt like that, you mean? Has Dalton comma James, he of the thirty-one broken bones, two bullet wounds, nine puncture wounds, and four stainless steel screws—and nine staples, don’t forget those—has this man who literally trailed blood into your hospital tonight ever tried to run away from the pain, only to learn just like you did that you take it with you no matter where you go?

You want to check his medical file for the answer. You wonder if maybe it’s on the same page that lists his alma mater. You want to laugh but that would be inappropriate.

But you have your answer. You may not want to believe it, because it’s safer not to. But the working-class hero with the NYU degree and the studiously sculpted body and the equally studiously sculpted speech, with the blue eyes and the smile, with the thirty-one broken bones and two bullet wounds and nine puncture wounds and four stainless steel screws and, soon, nine staples—he told you already.

He told you, when he said Pain don’t hurt.

No, you think. By comparison? No. No, it does not.

You’re still smiling, you realize, you’re still smiling and he’s still smiling as you turn to grab the stapler. As you feel his body through the latex of your glove and begin to repair what was broken you think Pain don’t hurt and you wonder how long the smiling will last.

101. The Third Rule, Verse 4

April 11, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, for the fourth time, is the third.

3. Be nice (continued)

“I want you to remember,” says Dalton, “that it’s a job. It’s nothing personal.”

Thus far, Dalton has explained the third and simplest of his Three Simple Rules in comparatively painstaking detail. He has articulated its Great Commandment. He has preached the Parable of Someone Getting in Your Face and Calling You a Cocksucker. He has emphasized its communal nature. And now he says it’s nothing personal?

I’d like to take this opportunity to introduce you to a man named Gyp Rosetti.

ROSETTI: “Bone for tuna.”

TONINO: What?

ROSETTI: “Bone for tuna.” What the fuck’s that’s supposed to mean?

TONINO: Oh. The kid’s Irish. The pronunciation was off. I think he meant—

ROSETTI: I know what he meant. Who the fuck is Nucky Thompson to wish me good luck? And in Italian, no less, like he’s mocking me? He’s real cute, I’ll fucking tell you. Sets me up to lose, pulls our whiskey deal at the last minute, then it’s buon fortuna like he’s rooting for me to get back on my feet. Push me off a cliff, why don’t you.

TONINO: Sure, I mean—

ROSETTI: Good luck flapping your arms on the way down! Am I right?

TONINO: Sure, I mean—

ROSETTI: Real attitude on him. Scrawny Irish prick. I need his blessing to make my way in the world?

TONINO: He w—

ROSETTI: I need him? To lecture me? “Nothing’s personal”? What the fuck is life if it’s not personal?

So you can see Dalton’s dilemma. Here he is, new in town, new in the job, new to these men, whose job it is to physically fight, restrain, and eject other men. His first order of business is to fire two of their coworkers, neither particularly well-liked, but each emblematic over his power over their employment and thereby their lives. He’s told them It’s my way or the highway and rattled off a list of undesirables who frequent the bar, a state that’s going to change. The implication is clear: His way is superior to theirs, which has demonstrably failed. From there he launches into a disquisition on bouncer conduct that is rife with paradox and contradiction as well as comprising a nearly diametrically opposed approach to the craft than that which they have heretofore pursued. After all this, after telling these violent men how to do their violent jobs by moderating their interactions with other violent men under the threat of termination, Dalton has the temerity to tell them that when the time comes and they are being pelted with verbal and physical abuse and they must decide whether and how to strike back, that all of this is nothing personal? Doesn’t he see how they would take this? Doesn’t he know it reads as insanely pollyannaish at best, insulting at the most reasonable, and downright dangerous at worst? When confronted with well-meaning advice by someone with whom you are at odds—and what is a worker if not at odds with the boss—even the most anodyne bromide, like wishing an associate “good luck” in his native language when a business deal goes south, feels like fighting words. Doesn’t Dalton realize that telling these men in this context that this job is nothing personal is tantamount to throwing down the gauntlet and fucking daring them to take it personal?

Yes. Yes he does.

If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig.

(to be continued)

102. Mirror

April 12, 2019103. Dump truck

April 13, 2019This much, at least, is not in dispute: When Dalton’s first night at the Double Deuce is winding to a close, Morgan, who is skeptical about the man’s physical prowess, tells him the following.

“You know, I heard you had balls big enough to come in a dump truck, but uh…you don’t look like much to me.”

“Opinions vary,” Dalton replies, and Morgan is temporarily bested.

But while that may settle the issue for the involved parties, we are left with unanswered questions. To wit: When Morgan says he’s heard Dalton’s balls are big enough to come in a dump truck, does he mean A) a dump truck is required to carry them on account of their large physical size, or B) a dump truck is required to receive Dalton’s ejaculate load due to the copious amounts of semen his big balls produce? “Come” as in “arrive,” or “come” as in “cum” as in “ahh skeet skeet motherfucker”? As Dalton himself might say, opinions vary.

Below you’ll find the best cases I can make for and against the two competing interpretations.

Morgan means “come” as in “travel”

PRO:

- Saying someone has “big balls” is a way of saying they’re unusually gutsy or tough, traditional characteristics, one would think, of a famous bouncer

- Dump trucks are known for carrying things placed in them and can accommodate substantial size and weight, making for a strong metaphor

CON:

- Placing his gargantuan sack in a dump truck would leave the rest of Dalton’s body at something of a loss were the truck to go anywhere, the Double Deuce’s parking lot for example

- Dump trucks typically transport dirt, rubble, or refuse, none of which describe Dalton’s testicles

Morgan means “cum” as in “bust a nut”

PRO:

- The measure of a man’s balls could in theory be taken by the size of the receptacle required to contain a full emission of his seminal fluid; from this we can infer that were the bed of a dump truck required to catch all of Dalton’s ropes in their entirety, his yarbles must needs be very big indeed

- Simply weighing or determining the circumference of Dalton’s ballbag implies passivity on his part, while the thought of Dalton milking, or causing a third party to milk, his dick into the back of a construction vehicle demonstrates the activity and agency becoming of a bouncer

CON:

- Dump trucks are not recommended vehicles of liquid waste; absent a watertight truck bed Dalton’s jism could seep through the seams and on to the road surface below, causing a potential traffic hazard and thus negating the central idea of the metaphor as a means to convey his professional clout and skill

- The size of Dalton’s cock, which due to the nature of the orgasmic process would play an indispensable part in the process of cumming into a dump but not in the process of simply transporting Dalton’s huevos in one, goes conspicuously unremarked upon

CONCLUSION:

Occam’s razor suggests Morgan means he’s heard that Dalton’s balls are so big he would not be surprised to see them being carried by a dump truck, not squeezed like lemons into one. However, the imagistic approach of the latter interpretation has much to recommend it as a hypothetical alternative.

104. I Thought You’d Be Bigger Vol. 2: Cody

April 14, 2019For a recurring joke, “I thought you’d be bigger” gets deployed with a pretty broad affect range. The first person we hear say this to Dalton is Frank Tilghman, whose delivery is difficult to characterize in any way but sexual. The second is Cody, lead singer of the Jeff Healey Band in the Road House Universe, and his delivery could not be further removed from his and Dalton’s mutual employer.

Dalton arrives at the Double Deuce, takes in the scenery, and discovers that the bar band are old friends. He sneaks up on the lead singer with the help of his identical and yet somehow not related bandmates, with a theatrical finger-to-the-lips Marian-Madam-Librarian “shhhh” gesture he shares with each. He hands Cody a towel to mop up the accumulated sweat and projectile beer on his face, for which Cody thanks him. “You play pretty good for a blind white boy,” Dalton says, beaming. Recognition dawns in Cody’s face. “Yeah, and I thought you’d be bigger,” he jokes, and the two embrace, laughing.

I’m gonna level with you: I love this moment. Why? Because it’s one of the only times in the film where Dalton is completely at ease. He’s been reunited with an old friend, a peer, not someone he has to impress, not someone he has to instruct, not someone who mentored him, not someone he needs to mentor. They know each other well, but as colleagues rather than sensei and student. They pass feverish gossip about old times and current times: “Man, this toilet is worse than the one we worked back in Dayton,” Cody says. He also mentions that he and “the boys” heard Dalton was headed to Jasper, presumably from Tilghman, although word among barfolk travels far and fast of course. Dalton therefore does not need to dazzle Cody, nor earn his respect. Cody’s been sitting on his barstool on stage, guitar in his lap, waiting to welcome Dalton with open arms. Anyone would be happy to step into that situation.

But most important of all is that this exchange is just that: an exchange. Dalton ribs Cody in a way he is, presumably, accustomed to being ribbed—that his chosen genre and evident skill are anomalous given his race and disability. Cody thinks this is funny to hear, which indicates he’s heard it a million times before. He uses “I thought you’d be bigger” as a riposte, indicating that these two have shared late-night “You know what people say to me all the time and totally drives me nuts?” conversations over Miller Genuine Draft when the patrons of that toilet in Dayton have long since retired for the evening.

The point I’m trying to make is this: While Tilghman’s “I thought you’d be bigger” is off-putting and invasive, Cody’s is familiar, friendly, and inviting. Eat your heart out, Snake Plissken and “I heard you were dead.” Patrick Swayze and Jeff Healey just took you to catchphrase school.

105. Fate

April 15, 2019One hundred essays into a year-long Road House writing project, I feel about the film’s attempts to coin catchphrases and aphorisms exactly the way I felt when I’d written no essays at all: yikes. I mean, Does a hobbyhorse have a wooden dick, folks. Balls big enough to come in a dump truck. The writers have a relationship with the English language only slightly less estranged than their relationship to male sex organs.

But they can’t all be losers.

Just after the dump truck incident, a grumpy Morgan (there is no other kind of course) stomps over to Cody, whom he knows has a preexisting relationship with their mysterious new colleague. “This Dalton character,” he grumbles, “what’s his story?”

“His story is, you fuck with him and he’ll seal your fate,” Cody replies.

Now that’s how it’s done.

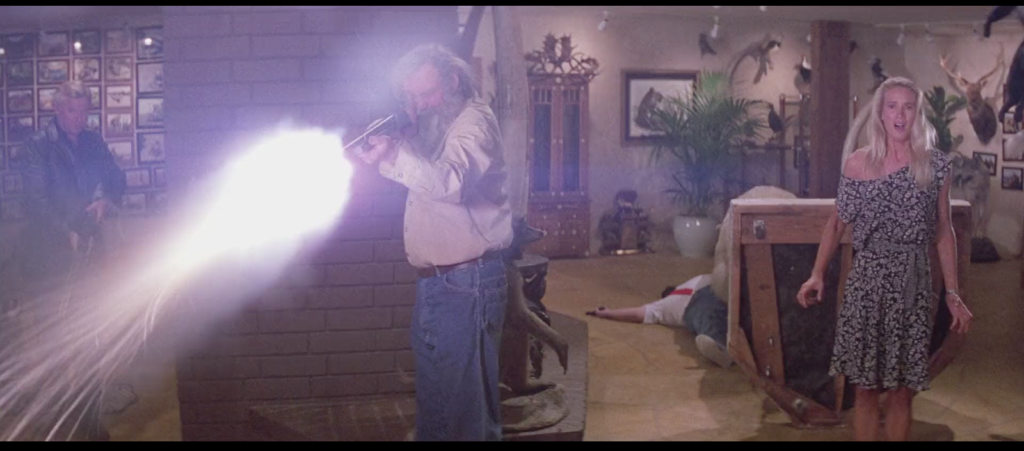

It’s a marvelous exchange insofar as it’s a rare moment when two characters have a conversation during which Dalton is neither a participant nor present. These are few and far between in this film, to the point where they stand out like sore thumbs each and every time. Off the top of my head, there’s this conversation, there’s Brad Wesley beating up the bleeder, Wesley and Jimmy talking to Red briefly after Dalton departs his store, and Jimmy and Ketchum spying on Dalton and Elizabeth from afar. Unless you count Wade Garrett breaking up shenanigans at a strip joint prior to receiving a call from Dalton, or Wade Garrett asking for Dalton’s whereabouts when he arrives at the Double Deuce, or Wesley’s goons making small talk prior to Dalton’s final assault on the Wesley compound, or Steve and Agnes doing their regular Saturday night thing before Dalton pops in and fires him—all of them scenes that exist so that Dalton can join them in progress—that is it. This is Dalton’s world, and what a treat to see other people live in it.

And who are the people in question this time around? Blind white blues musician Jeff Healey and hardcore wrestling legend Terry Funk. For Road House fanatics this is like the De Niro/Pacino diner scene in Heat.

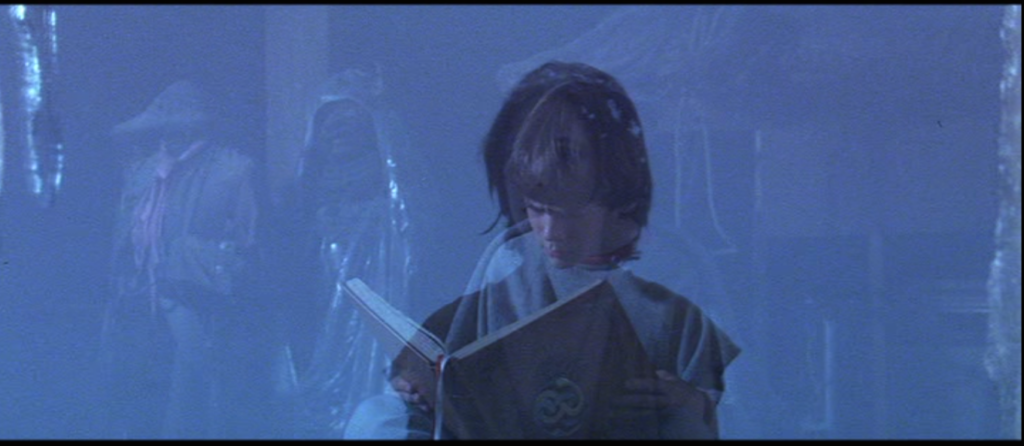

But don’t think it’s just some goofy novelty act. (I didn’t say “Don’t think it’s some goofy novelty act,” mind you, I said “Don’t think it’s just some goofy novelty act.) Throughout this project I’ve been impressed by what the…let’s say non-traditional actors bring to the table. The naturalism Terry Funk brings to his role as an enormous man who gets paid to get angry and beat the shit out of people with tables is obvious. But spare a thought for Jeff Healey, too, who sounds like exactly what he is supposed to be: a guitar player chatting with dudes in bars. It works when he’s serving as a welcoming presence for Dalton, the one character he neither needs to intimidate nor impress, and it works when he drops the “hey man lemme put this here guitar down and buy you a beer” schtick and describes his friend like he’s the fucking Shogun Assassin.

Because that’s the message of “you fuck with him and he’ll seal your fate,” isn’t it. He won’t just kick your ass, or kill you, or make you wish you were never born or blah blah blah. Like a Norn with a mullet, he’s got the thread of your life in his hands, and if you step to him you’re going to find out exactly where that thread ends.

There’s another implication here that must be considered: Fate is predestined. Cody’s description of Dalton, then, is of one who will mete out the appropriate and appointed sanction to those who cross him, no more and no less. Perhaps it will be your fate to disappear from the movie a third of the way through and never return, like Karpis. Perhaps it will be your fate to pass out from terror when a stuffed polar bear is dropped on you and then emerge reborn, your sins forgiven, like Tinker. Perhaps it will be your fate to be murdered offscreen while wearing moonboots, like Morgan. Whatever the case, Dalton is not making the news, he’s simply delivering it to your doorstep.

It’s precisely the right description for the Dalton Path. Remember Rule Three, Verse Four: “It’s a job. It’s nothing personal.” What can be more impersonal than fate? And who better to do the job of sealing it?

106. Sightings

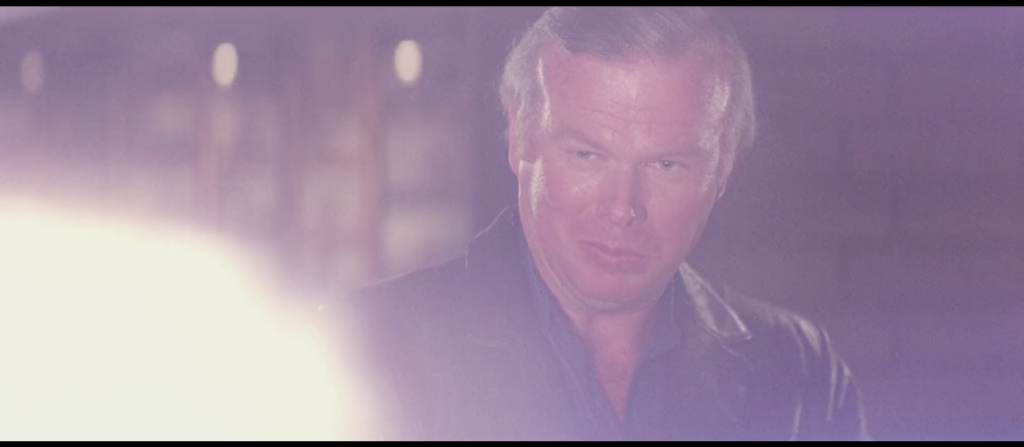

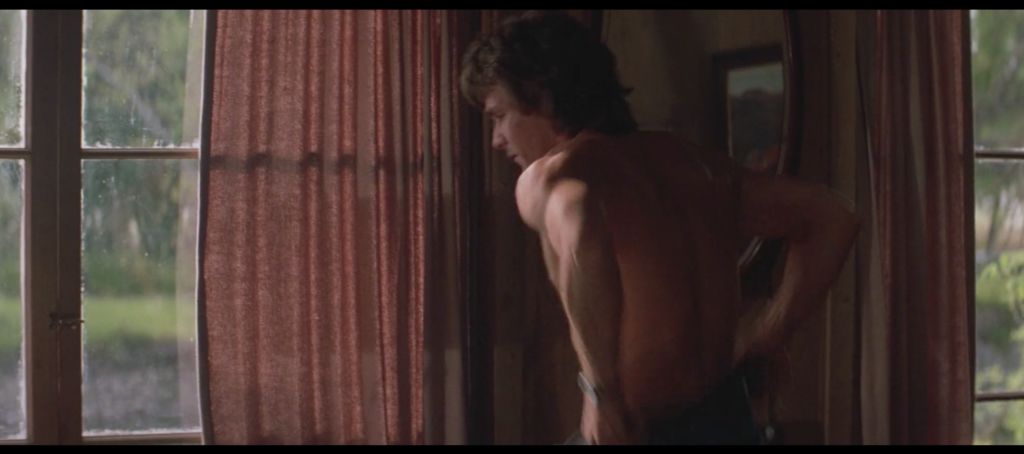

April 16, 2019Flipping through my copy of Road House today, waiting for inspiration to strike, I came across one of my favorite goofy moments in the movie: Brad Wesley stopping his ATV, which he’d been driving around he lawn of his mansion or something I guess, in order to watch and gently scoff at Dalton doing tai chi across the river. The combination of factors at work here—a shirtless and glistening Patrick Swayze performing tai chi on the Missouri farm where he lives during his stint as making six figures at a local shithole as part of his career as a famous bouncer, a deranged JC Penney enthusiast finding this interesting enough to park his Big Wheels and watch but ultimately come away unimpressed, as if he’d expected better form, or a dryer torso—is irreplicable in any other film.

But something hit me about Dalton, as seen from Wesley’s point of view in this moment. Something that I have seen in another film, albeit not a feature. Something that comes close to capturing our sense, and perhaps Wesley’s sense too, that when we look at Dalton we’re seeing something that defies comfortable categorization. Something wild, mysterious, dangerous, untamed, and all but extinct.

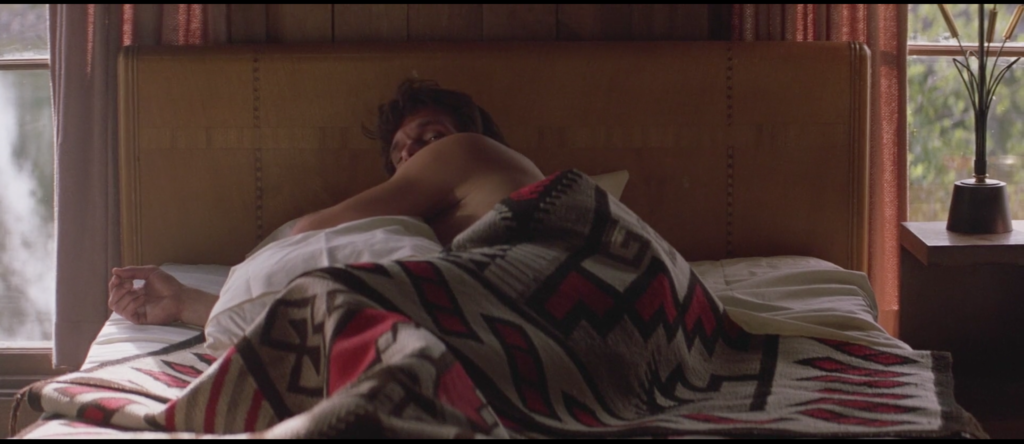

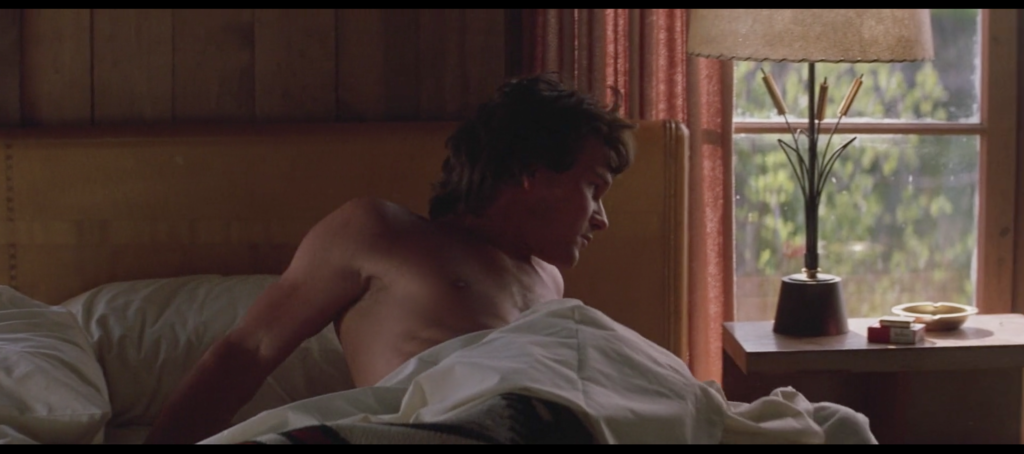

107. Dalton’s back

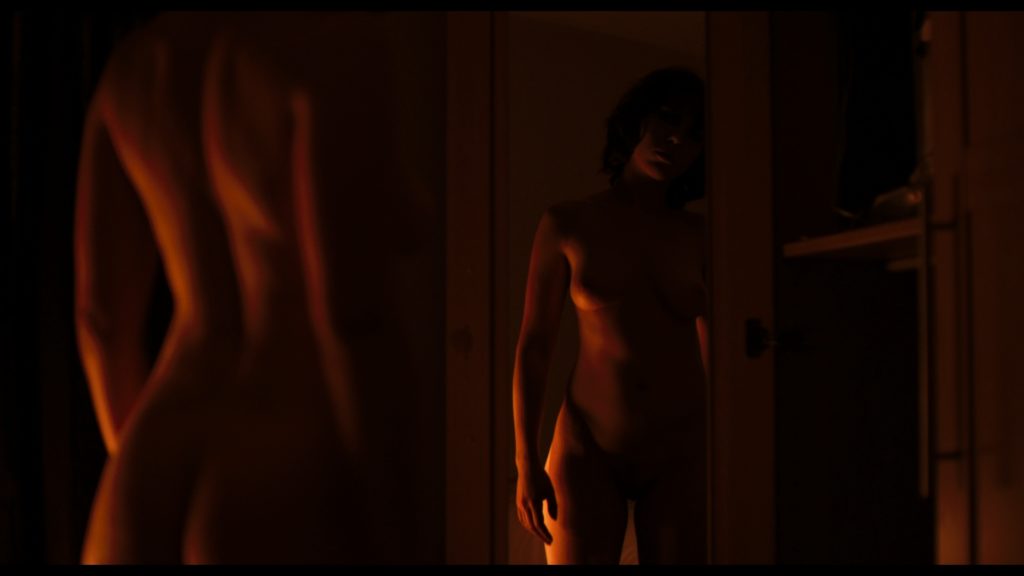

April 17, 2019Broad-shouldered, slim-waisted, corded with muscle, Dalton’s back is a perfect thing, an inverted arrowhead of sex. The sun glistens and gleams from every sweat-soaked ridge and cleft. At times you’d swear it’s a source of light itself. The camera orbits Dalton throughout his riverside tai chi routine and his whole body, or at least the upper half which is mostly what you see, is a marvel of course. But his back looks like it was manufactured, by the company who designed the clockwork opening credits for Game of Thrones maybe, or the people who adapted H.R. Giger’s artwork into sculptures for his house. During his waterside tai chi routine both Emmett, his friend, and Wesley, his enemy, stop what they’re doing and just…stare. It’s impossible to blame them. Or us. Dalton’s character is built on the sense that his many aspects—fighter, lover, road warrior, philosopher, rich famous guy, aw shucks everyman, killing machine, pacifist, beer-drinker, binge-reader, master, apprentice—all work in concert to make the man. Road House too, when appreciated properly, is less a film than an ecosystem: hyperefficient factory-made late-’80s star vehicle, barely competent incoherent MST3K fodder, rock-solid action flick, more obvious than usual homoerotica, smarter than it looks, dumber than it realizes, a Ben Gazzara film, a Terry Funk film. When you watch Dalton’s flawless, godlike arms and traps and shoulderblades flex and contract in harmony, you’re watching the character and the movie in metonymy. You’re watching a real physical thing, Patrick Swayze’s beautiful beautiful body, do what Patrick Swayze’s character and Patrick Swayze’s movie are also doing. As below, so above.

108. Dead man revisited

April 18, 2019“You’re a dead man,” Morgan tells Dalton when he gets fired. Carrie Ann, Morgan’s now-former coworker, may not share his idiosyncracies regarding where to place the emphasis when speaking, but she does share his sentiment.

The morning after Dalton’s momentous first night in the Double Deuce’s employ, Carrie Ann heads over to his luxury barn to feed him breakfast and, lucky for her, see his bare ass and reenact that gif of Ariel the Little Mermaid leaning on a rock as a huge gush of water erupts around her as a result.

But she brings business to go along with her culinary and visual pleasure. Firing Pat McGurn, one of the Double Deuce’s bartenders, is something Dalton should not have done, she tells him. As a mostly mute (but for grunting and an admittedly sincere-sounding “thank you”) Dalton sits down with a lit cigarette in his mouth and no shirt on his torso, disgustedly tossing aside the bacon and egg sandwich or whatever it is she brought him and moving in on the coffee, Carrie Ann starts cracking up while saying “Oh my god.”

“What is the joke,” Dalton asks, sounding like a cop on a TV show who just got a call at 3:30am saying there’s been another homicide down at the docks.

“Well, there’s no joke,” Carrie Ann says. “I just think I’m looking at a dead man, though.”

“Seems everywhere I go I hear that same joke,” Dalton mutters, shaking his head.

“Yeah? Well, something tells me you bring it on yourself,” Carrie Ann says saucily, nibbling on her breakfast in eating the popcorn/sipping the tea mode.

The variation in affect between the two actor makes it tempting to write this scene off as a minor bit of light-comedy character building. Dalton, who is hung over from a long night reading A River Runs Through It, is gruff and world-weary, too tough to worry and too tired to care. This is just how he lives his life: an endless cycle of naked wake-ups, shirtless stretching, cigarette-flavored coffee for breakfast, some tai chi or perhaps hitting the heavy bag for a workout, grabbing an unstructured jacket, heading to work to get stabbed by various men in the course of kicking their asses, repairing the damage done to his car by those men on their way off the premises, driving back to his luxury bachelor pad right next to the horse pen, taking off his shirt, reading a book, spying on Brad Wesley’s in-ground pool orgy, and finally doffing his jeans and hitting the sack. If during the course of those events people pronounce him a dead man, it’s a job, it’s nothing personal. And Carrie Ann is just the platonic female foil, the funny best friend, who’s able to poke holes in his machismo but not actually call his narrative into question or anything of that threatening nature.

But Carrie Ann, the drinking man’s Cassandra, also knows well that the only person who can truly save Dalton is himself. A warning out of professional courtesy, a gesture of solidarity with a new friend, an excuse to go over to the hottest guy in town’s place—it’s probably all three of these things. But in reality what he’s saying is “I can’t help being what I am,” as a stoic positive; she’s saying it too, but as a cheerily black-comic negative. Worst of all, it’s a direct challenge to the Rules. All that talk about expecting the unexpected, remembering it’s a job, it’s nothing personal, be nice until it’s time to not be nice, watch my back and each others’, and so on…earns him death threats “everywhere I go”? Okay dude, her twinkling eyes and cocked head seem to say, it’s your funeral. We’d expect no less of a dead man.

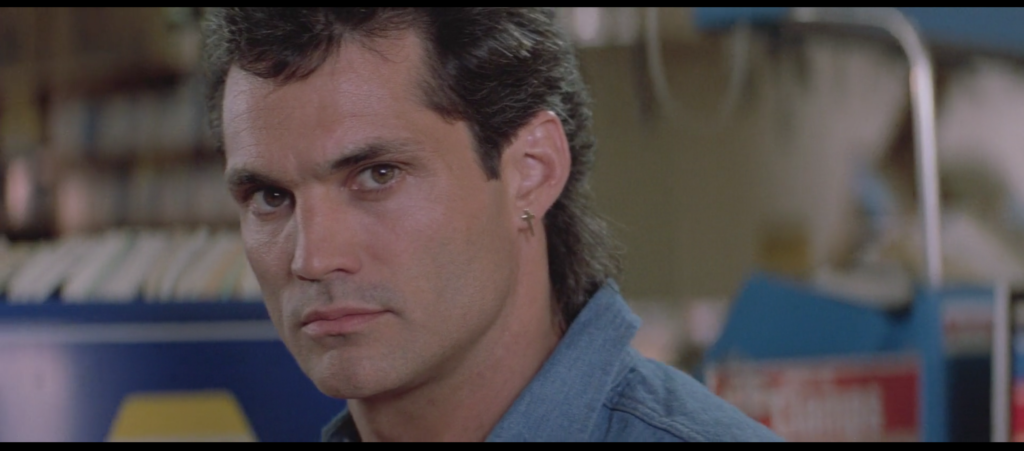

109. We’re not so different, you and I

April 19, 2019“What he says, goes.” “It’s my way or the highway.” “It’ll get worse before it gets better.” Few action-movie cliches go unuttered in Road House, along with several no action movie has ever used before or since. (“I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick.”) Remarkably, however, we never get a good “We’re not so different, you and I” out of Brad Wesley. There are moments when it seems he’s coming close—Mike Nelson notes this during the climax in his excellent solo RiffTrax on the movie, the first of three or four he and the other MST3K vets have recorded—and the Doc draws the parallel herself when things get really hairy, but the villain whose specialties are taunting Dalton and opening JC Penneys never goes there.

Given Rowdy Herrington’s direction, perhaps actually coming out and saying it would be gilding the lily. No, no one says “We’re not so different, you and I.” But in scene after scene both Dalton and especially Wesley react to annoyances and misfortunes with the exact same way. They cock their head to the side, shake it in “get a load of this” disbelief, and half-smile “ya just gotta laugh”–style. Dalton does it when he emerges from the Double Deuce after his first night of work and discovers his car has four flat tires, a broken antenna, and a shattered windshield (Nelson, in his RiffTrax again: “I have hours of backbreaking labor ahead of me. It’s actually pretty funny!”); Wesley does it the very next day when he spots Dalton practicing tai chi. You get variations on it for matters as minor (no pun intended) as Dalton finding Steve in flagrante with a young lady in the back room, and as grave as Wesley walking through his mansion and discovering the dead bodies of all his henchmen. Wade Garrett and Elizabeth may not do the head-shake thing but they spend the entirety of their three-person date with Dalton grinning at each other in that same can-you-believe-it way.

It can hardly be said that Ben Gazzara and Patrick Swayze have similar acting styles or training, so I can only assume this was Harrington’s go-to instruction, like George Lucas’s infamous “faster, more intense” on the set of Star Wars. But like so many of the film’s other foibles this winds up feeling both endearing and unique. Vandalism, tai chi, dead bodies, people fucking during their 15 minutes—Road House‘s reaction to each is “grin and bear it,” and there’s no other film with quite so untroubled an outlook on the totality of human experience. As Red Webster put it, “That’s life. Who can explain it.”

110. Wound

April 20, 2019But one of the soldiers with a spear pierced his side, and forthwith came there out blood and water. (John 19:34)

There is a nicely-vulgar joke about Christ: the night before he was arrested and crucified, his followers started to worry – Christ was still a virgin, wouldn’t it be nice to have him experience a little bit of pleasure before he will die? So they asked Mary Magdalene to go to the tent where Christ was resting and seduce him; Mary said she will do it gladly and went in, but five minutes after, she run out screaming, terrified and furious. The followers asked her what went wrong, and she explained: “I slowly undressed, spread my legs and showed to Christ my pussy; he looked at it, said ‘What a terrible wound! It should be healed!’ and gently put his palm on it…” So beware of people too intent on healing other people’s wounds – what if one enjoys one’s wound? (Slavoj Žižek, Event)

Pain don’t hurt. (Dalton, Road House)

111. He Is Risen

April 21, 20191 And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, had bought sweet spices, that they might come and anoint him.

2 And very early in the morning the first day of the week, they came unto the sepulchre at the rising of the sun.

3 And they said among themselves, Who shall roll us away the stone from the door of the sepulchre?

4 And when they looked, they saw that the stone was rolled away: for it was very great.

5 And entering into the sepulchre, they saw a young man sitting on the right side, clothed in a long white garment; and they were affrighted.

6 And he saith unto them, Be not affrighted: Ye seek Jesus of Nazareth, which was crucified: he is risen; he is not here: behold the place where they laid him.

7 But go your way, tell his disciples and Peter that he goeth before you into Galilee: there shall ye see him, as he said unto you.

8 And they went out quickly, and fled from the sepulchre; for they trembled and were amazed: neither said they any thing to any man; for they were afraid.

9 Now when Jesus was risen early the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had cast seven devils.

10 And she went and told them that had been with him, as they mourned and wept.

11 And they, when they had heard that he was alive, and had been seen of her, believed not.

—Mark 16:1-11 (KJV)

Well, there’s no joke—I just think I’m looking at a dead man, though.

—Carrie Ann, Road House

112: I Thought You’d Be Bigger Vol. 3: Doc

April 22, 2019Dalton and Dr. Elizabeth Clay’s meet cute is a very sexy scene, if you ask me, which by reading this blog you have in effect done. A lot goes into making it sexy, too. You start with Patrick Swayze and Kelly Lynch, two extremely attractive human beings. From there you step to the difference in their sexiness: Swayze’s Dalton, shirtless, exposed, vulnerable yet also tough in his willingness to be vulnerable, to be exposed, to be shirtless; Lynch’s Doc, whose intense French braid, enormous glasses, and shapeless white coat emphasize rather than obscure her beauty, as if you’d put glasses and a lab coat and a wig from a Halloween store on the Venus de Milo. There’s the intimacy of the scene too, of the act of a woman touching and healing a man wounded by physical contact with other men, sublimated eroticism piled on sublimated eroticism like they’re fucking. There’s the BDSM angle in the form of the Pain Don’t Hurt koan and the power-exchange positioning of their bodies and faces. Maude Lebowski might suggest that Dalton’s wound is highly vaginal. I for one have pulled off that lapsed-Catholic trick of eroticizing blasphemy, so if you remember where Christ was wounded you’ve got that going for you as well.

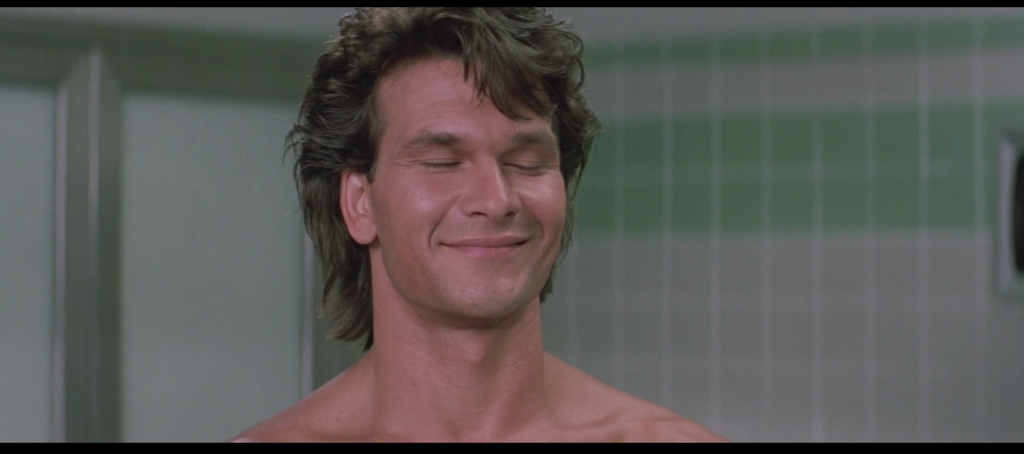

But the sexiest thing about it is Elizabeth’s voice when she pauses on her way out of the exam room, turns, and says “You know…for that line of work I thought you’d be bigger,” and Dalton’s utterly guileless smile and laugh before he responds with a self-effacing “Gee, I’ve never heard that before.” Man oh man are these two into each other! You can hear it! Elizabeth’s voice is so soft, almost tremulous with the curiosity that caused her to stop and turn back towards her patient. (She’s like Lot’s wife if Lot’s wife dodged the salt thing and got to go back to town and fuck.) Dalton is delighted to hear this fascinating woman, his intellectual and physical peer, say something he’s heard a million times before—it means he can contextualize her as a part of his life now, even if things don’t work out, and for the moment that’s good enough for him. Do we ever see Dalton close his eyes with pleasure like he does here, at any other point in the movie? Not that I can think of. Do we ever hear anyone say “I thought you’d be bigger” with such directness and wonder—not some weird power-trip come-on, not bants between the lads, but just a person sizing up another person they’re attracted to, in that person’s presence? No way. Woof, man, these two are hot for each other, and it leaks out of them and into their voices as they say goodbye. They know they’ll be saying hello again soon.

113. Signs

April 23, 2019Dalton goes to a laundromat to make his phone calls. There’s no phone in his luxury barn, we know this from Emmett’s anti-sales pitch when he rents the place. Either he doesn’t have opening privileges for the Double Deuce or he wasn’t in that part of Jasper (the Auto Parts/Boat Sales/Hellhole district) when he needed to make the call. Either way, here he is, inside this beautiful laundromat that I’m almost positive you couldn’t find somewhere in California in 1989 or thereabouts, reaching out and touching his mentor Wade Garrett. He’s wondering if Wade’s heard anything about a guy named Brad Wesley, because (I’m inferring) any man who’d make trouble for a cooler stands a decent chance of having been watchlisted by veteran cooler agents across the country. Wade comes up empty, though using his cooler-sense he asks Dalton if he’s gotten into any kind of trouble. “Nothing I’m not used to,” he says, before adding with a chuckle “but it’s amazing what you can get used to, isn’t it?” Wade banters back, they say their goodbyes, that’s that.

But look what happens after Dalton says Brad Wesley is nothing he’s not used to.

Suddenly a sign appears where none had been before. The sign lists the cost of using one of the laundromat’s large machines: NINE QUARTERS. I never noticed this until just this afternoon.

So here’s the situation. You can choose to believe this is just the kind of harmless, almost invisible continuity goof that happens in nearly every movie.

Or you can take it as a sign [pause for reader recognition of the awesome implications of the connections being drawn here] that for dismissing Brad Wesley, a price must be paid.

Search your cooler-sense. You know what is true.

114. The Nine

April 24, 2019Nine quarters, says the sign that appears in the middle of Dalton’s pivotal conversation with Wade Garrett, right after he blows off the threat presented by Brad Wesley. Right away we can see that reality has warped a little, that a glitch in the matrix has appeared. As well it might: Dalton has just underestimated his opponent and failed to expect the unexpected, a violation of his own First Rule. And for that, a price must be paid.

But what if there’s more to it than that?

It was not I who set myself on this path, but reader @RoddySwears. It was he who noted the numerological significance of the established price. Nine quarters. Two dollars and twenty-five cents. $2.25. 2 + 2 = 9.

What could such a specific prophecy mean?

Then I realized.

The Nine are abroad.

115. Mijo

April 25, 2019“What’s goin’ on, mijo?”

This is how Wade Garrett opens his phone conversation with Dalton, the first exchange the student and the master have in the film. Mijo is the term of endearment with which Wade refers to Dalton throughout the film. Mijo means “son.”

I wouldn’t read too much into that if hahahaha just kidding, boy oh boy is this a fecund (virile?) word choice! This kind of affectionate diminutive is of course common to men of a certain age when addressing younger men. It’s certainly common in Road House. O’Connor, the Bleeder himself, calls Dalton “son” prior to this exchange. Brad Wesley refers to the men he pays to beat people and destroy property for him as “my boys.” On the flip side, Morgan sneeringly calls Wade “Dad” when they jump ugly upon Wade’s arrival in Jasper. Fatherless sons and sonless fathers in this movie, almost to a man.

Let’s step back for a moment though. Whatever the implication of the term, Road House is emphatically not some sort of prophetic look at the future of nerd culture, in which daddy issues are the prime motivator for fiction, both in terms of what the fiction is about and the men who write it, most of whom have few thoughts in their head deeper than “You shouldn’t have yelled at me for staying inside to read The Incredible Hulk instead of playing pee-wee league football, Dad.” I just find it hard to believe that, for example, people stranded on a mysterious island with extraordinary powers, supernatural threats, and a relict science cult only want to look upon the faces of their fathers again, or that the Alien franchise is improved by recreating the Genesis/Frankenstein creation myth with Michael Fassbender instead of leaning hard into the birth-phallus nightmare Giger gifted poor idealess Ridley Scott with back in the day, or…I dunno, I think Chris Pine Captain Kirk is really worried about his dad for some reason in those Star Trek movies.

What does this have to do with Road House, you might ask? On one level, nothing, I’m just getting a few licks in on the sentimental excesses of JJ Abrams & Damon Lindelof. But what I’m really trying to say is that the actual father-son dynamic, in terms of a younger man rebelling against but ultimately (in nerd-culture usage anyway; rebellion against the father is always a mistake) looking up to an older man who offers him guidance, remonstrance, and ultimately approval, and an older man needing a younger man to live through vicariously, help avoid painful mistakes, and wrestle with being supplanted—that’s not here. Whatever the age difference (“Wade Garrett’s getting old”), Dalton and Wade are peers at this point. The advice Wade gives him is not much more paternalistic than that given to Dalton by Elizabeth or Emmett, or by Dalton to the employees of the Double Deuce and the small businessmen of Jasper, all of whom are his senior by a wider margin than Wade.

Mijo is rather applicable in two other ways. First there’s the “all these bitches is my sons” Nicki Minaj spin on it, sans the pejorative implication. The Dalton Path is directly descended from the Way of Wade Garrett. Dalton brings his own philosophical spin to things, but from their rangy fighting styles to their emphasis on both emotional and physical efficiency they’re father and son alright.

The second is a bit trickier to unpack, or unzip as it were. If Dalton is Wade’s son, Wade must needs be Daddy. Again, I don’t think this usage applies to Dalton himself, except perhaps with third-party women like Elizabeth as a proxy. I do know that the Doc clearly has Wade up on the exam room table of her mind within about two seconds of seeing him for the first time, and that the night is still young when Wade first shows her, the girlfriend of his best friend and student, his pubic hair. Wade isn’t into the Tumblr Daddy Dom suit-and-tie capitalist-pig shit, not at all. He simply has the steady hand, stubbly chin, and built-for-action body of a man who’s used to being in charge. For every mijo, there is an equal and opposite papi.

116. Bad Barfolk

April 26, 2019All barfolk are not created equal. Take this fellow, who tends bar at the strip joint where Wade Garrett is working when first we see him. We know Wade Garrett is the best, because Dalton has said so. We know he’s getting old, because Frank Tilghman has said so. We know this doesn’t matter, because he just charmed about a dozen Marines out of either storming the stage to sexually harass the dancers or beating the shit out of him for telling them not to. Why the best cooler alive is working a topless bar roughly the size of your uncle’s basement is beyond me, but then there’s a lot I don’t understand about cooler economics in this film. Did the titty bar impresario pay Wade five hundred large a year to clean up a place with a seating capacity of about forty semi-erect men? Your guess is as good as mine.

Here’s one thing I know, though—or thought I knew: Barfolk know who Wade Garrett is. Barfolk know who Dalton is. On the very first day of this project we established that Dalton has a famous name among barfolk but is not necessarily visually recognizable, whereas people know who Wade is on sight. But that shouldn’t make a difference in this scene, in which Dalton calls Wade’s place of employment to ask his advice on the matter of Brad Wesley. When Dalton says “Wade Garrett please. The name’s Dalton” or whatever his phone greeting is, that should be sufficient to alert anyone on the other end of the line that they’re standing witness to history: the two best coolers in the business have something to say to each other.

This doofus above, though? When he tells Wade he’s got a phone call, he describes the caller as “Some guy name a’ Dalton.”

What kind of barman are you, sir?

Have standards at your establishment dropped so precipitously that the name of Dalton does not echo across its pool tables and down its elevated stage? Why would Wade Garrett be caught dead in such a place? If you don’t know Dalton, you’re not worth knowing, or at the very least not worth buying a drink from.

Perhaps you’re saying “Well Sean, if you stop and think about it for a second, they can hardly have this guy say ‘Garrett! It’s Dalton!’ because that would read as if Dalton is his friend as well as Wade’s. ‘Some guy name a’ Dalton’ is just screenwriter shorthand for ‘You have a phonecall from someone with whom I am not personally acquainted, and I’m relaying this information to you in a slightly rough-hewn manner. You’re rushing to judgment here.” To this I can only say bull shit, if anything I’m not rushing judgment enough. You either stick with the rules you yourselves established as the writers every time you showed any bar employee discover they were interacting with Dalton or I am forced to conclude you are casting aspersions on those who do not follow those rules. Sorry, topless bar bartender, if that is your real name, but you failed. I think it’s time for you gentleman to leave.

117. Smile

April 27, 2019They say a picture is worth a thousand words, a principle I attempt to disprove on a daily basis. But they’ve got me here, man. Wade Garrett may be getting old, this we know, but Wade Garrett’s the best. Indeed, based on our observations thus far, Wade Garrett is a supreme hardcase. In the past minute we’ve seen him a) observe the strip club from his perch at the periphery, like Batman surveying Gotham from the top of the cathedral at the start of a night’s work; c) wrangle a horned-up jarhead in the process of charging the stage to squirt women’s breasts with a battery-operated water gun at point blank range; d) do so so convincingly that the randyman’s brother Marines all squirt him with their water guns instead of teaming up to pound the shit out of a wiry old man who just stepped to them in front of attractive women they’re there to impress; e) earn a wink-and-a-promise from the lovely young woman whose performance he saved f) return that wink with a smile for which the phrase “panty-dropping” was invented g) do all this with a pronounced limp that makes him look like he just got off his horse after riding here all the way from Cheyenne with the law on his trail. Then he hears Dalton’s on the phone for him, and this goofy-ass grin is the result. I want you to keep this smile in mind as the rest of the film unfolds. Carry it with you during the trials and travails, triumphs and tragedies, strange pronunciations and displays of pubic hair that Wade and Dalton experience together in the days to come. Dalton lights up Wade Garrett’s life. And that’s all you need to know, son.

118. Aw Shit Hell Kid

April 28, 2019I hate to do this to Terry Funk of all people—it’s still real to me, dammit!—but Sam Elliott is here to take the Mispronunciation Title right out of his hands. Watching and hearing Wade Garrett talk to Dalton is fascinating for at least six posts’ worth of reasons, but the adventure of listening to him go to work on the English language is right there at the top. When Dalton asks him how he’s doing, he replies “Aw Shit Hell Kid I’m in Hog Heaven,” and it sounds like it reads there—like he’s reciting a song title he’s never come across before but thinks is pretty funny now that he’s seeing it for the first time. He closes out the call by telling Dalton “I’ll see ya later,” but not as one sentence, no, that would be the easy way out, and Wade Garrett is made of sterner stuff. “I’ll see ya,” he says, then pauses, then adds, “Later.” I’ve told people “See ya,” and I’ve told people “Later,” but never have I done so back to back. No one has done so back to back, until now. Sam Elliott decided he was gonna have some fun with the line “I’ll see ya later” and Rowdy Herrington had the good sense to let him, just as he did when Terry Funk got creative with “You’re a dead man.” People talk about Scorsese and De Niro and “You talkin’ to me?” or the tears in rain speech from Blade Runner, but real heads know.