Posts Tagged ‘wade garrett’

117. Smile

April 27, 2019They say a picture is worth a thousand words, a principle I attempt to disprove on a daily basis. But they’ve got me here, man. Wade Garrett may be getting old, this we know, but Wade Garrett’s the best. Indeed, based on our observations thus far, Wade Garrett is a supreme hardcase. In the past minute we’ve seen him a) observe the strip club from his perch at the periphery, like Batman surveying Gotham from the top of the cathedral at the start of a night’s work; c) wrangle a horned-up jarhead in the process of charging the stage to squirt women’s breasts with a battery-operated water gun at point blank range; d) do so so convincingly that the randyman’s brother Marines all squirt him with their water guns instead of teaming up to pound the shit out of a wiry old man who just stepped to them in front of attractive women they’re there to impress; e) earn a wink-and-a-promise from the lovely young woman whose performance he saved f) return that wink with a smile for which the phrase “panty-dropping” was invented g) do all this with a pronounced limp that makes him look like he just got off his horse after riding here all the way from Cheyenne with the law on his trail. Then he hears Dalton’s on the phone for him, and this goofy-ass grin is the result. I want you to keep this smile in mind as the rest of the film unfolds. Carry it with you during the trials and travails, triumphs and tragedies, strange pronunciations and displays of pubic hair that Wade and Dalton experience together in the days to come. Dalton lights up Wade Garrett’s life. And that’s all you need to know, son.

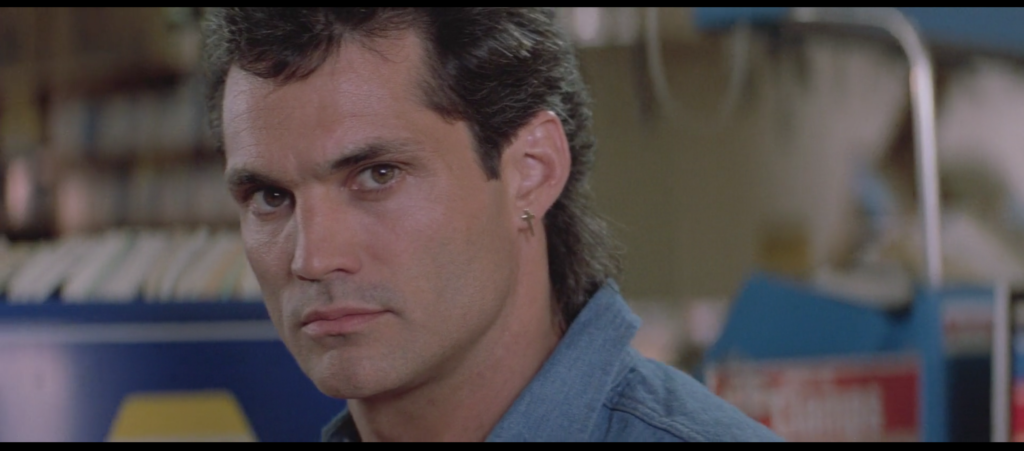

116. Bad Barfolk

April 26, 2019All barfolk are not created equal. Take this fellow, who tends bar at the strip joint where Wade Garrett is working when first we see him. We know Wade Garrett is the best, because Dalton has said so. We know he’s getting old, because Frank Tilghman has said so. We know this doesn’t matter, because he just charmed about a dozen Marines out of either storming the stage to sexually harass the dancers or beating the shit out of him for telling them not to. Why the best cooler alive is working a topless bar roughly the size of your uncle’s basement is beyond me, but then there’s a lot I don’t understand about cooler economics in this film. Did the titty bar impresario pay Wade five hundred large a year to clean up a place with a seating capacity of about forty semi-erect men? Your guess is as good as mine.

Here’s one thing I know, though—or thought I knew: Barfolk know who Wade Garrett is. Barfolk know who Dalton is. On the very first day of this project we established that Dalton has a famous name among barfolk but is not necessarily visually recognizable, whereas people know who Wade is on sight. But that shouldn’t make a difference in this scene, in which Dalton calls Wade’s place of employment to ask his advice on the matter of Brad Wesley. When Dalton says “Wade Garrett please. The name’s Dalton” or whatever his phone greeting is, that should be sufficient to alert anyone on the other end of the line that they’re standing witness to history: the two best coolers in the business have something to say to each other.

This doofus above, though? When he tells Wade he’s got a phone call, he describes the caller as “Some guy name a’ Dalton.”

What kind of barman are you, sir?

Have standards at your establishment dropped so precipitously that the name of Dalton does not echo across its pool tables and down its elevated stage? Why would Wade Garrett be caught dead in such a place? If you don’t know Dalton, you’re not worth knowing, or at the very least not worth buying a drink from.

Perhaps you’re saying “Well Sean, if you stop and think about it for a second, they can hardly have this guy say ‘Garrett! It’s Dalton!’ because that would read as if Dalton is his friend as well as Wade’s. ‘Some guy name a’ Dalton’ is just screenwriter shorthand for ‘You have a phonecall from someone with whom I am not personally acquainted, and I’m relaying this information to you in a slightly rough-hewn manner. You’re rushing to judgment here.” To this I can only say bull shit, if anything I’m not rushing judgment enough. You either stick with the rules you yourselves established as the writers every time you showed any bar employee discover they were interacting with Dalton or I am forced to conclude you are casting aspersions on those who do not follow those rules. Sorry, topless bar bartender, if that is your real name, but you failed. I think it’s time for you gentleman to leave.

115. Mijo

April 25, 2019“What’s goin’ on, mijo?”

This is how Wade Garrett opens his phone conversation with Dalton, the first exchange the student and the master have in the film. Mijo is the term of endearment with which Wade refers to Dalton throughout the film. Mijo means “son.”

I wouldn’t read too much into that if hahahaha just kidding, boy oh boy is this a fecund (virile?) word choice! This kind of affectionate diminutive is of course common to men of a certain age when addressing younger men. It’s certainly common in Road House. O’Connor, the Bleeder himself, calls Dalton “son” prior to this exchange. Brad Wesley refers to the men he pays to beat people and destroy property for him as “my boys.” On the flip side, Morgan sneeringly calls Wade “Dad” when they jump ugly upon Wade’s arrival in Jasper. Fatherless sons and sonless fathers in this movie, almost to a man.

Let’s step back for a moment though. Whatever the implication of the term, Road House is emphatically not some sort of prophetic look at the future of nerd culture, in which daddy issues are the prime motivator for fiction, both in terms of what the fiction is about and the men who write it, most of whom have few thoughts in their head deeper than “You shouldn’t have yelled at me for staying inside to read The Incredible Hulk instead of playing pee-wee league football, Dad.” I just find it hard to believe that, for example, people stranded on a mysterious island with extraordinary powers, supernatural threats, and a relict science cult only want to look upon the faces of their fathers again, or that the Alien franchise is improved by recreating the Genesis/Frankenstein creation myth with Michael Fassbender instead of leaning hard into the birth-phallus nightmare Giger gifted poor idealess Ridley Scott with back in the day, or…I dunno, I think Chris Pine Captain Kirk is really worried about his dad for some reason in those Star Trek movies.

What does this have to do with Road House, you might ask? On one level, nothing, I’m just getting a few licks in on the sentimental excesses of JJ Abrams & Damon Lindelof. But what I’m really trying to say is that the actual father-son dynamic, in terms of a younger man rebelling against but ultimately (in nerd-culture usage anyway; rebellion against the father is always a mistake) looking up to an older man who offers him guidance, remonstrance, and ultimately approval, and an older man needing a younger man to live through vicariously, help avoid painful mistakes, and wrestle with being supplanted—that’s not here. Whatever the age difference (“Wade Garrett’s getting old”), Dalton and Wade are peers at this point. The advice Wade gives him is not much more paternalistic than that given to Dalton by Elizabeth or Emmett, or by Dalton to the employees of the Double Deuce and the small businessmen of Jasper, all of whom are his senior by a wider margin than Wade.

Mijo is rather applicable in two other ways. First there’s the “all these bitches is my sons” Nicki Minaj spin on it, sans the pejorative implication. The Dalton Path is directly descended from the Way of Wade Garrett. Dalton brings his own philosophical spin to things, but from their rangy fighting styles to their emphasis on both emotional and physical efficiency they’re father and son alright.

The second is a bit trickier to unpack, or unzip as it were. If Dalton is Wade’s son, Wade must needs be Daddy. Again, I don’t think this usage applies to Dalton himself, except perhaps with third-party women like Elizabeth as a proxy. I do know that the Doc clearly has Wade up on the exam room table of her mind within about two seconds of seeing him for the first time, and that the night is still young when Wade first shows her, the girlfriend of his best friend and student, his pubic hair. Wade isn’t into the Tumblr Daddy Dom suit-and-tie capitalist-pig shit, not at all. He simply has the steady hand, stubbly chin, and built-for-action body of a man who’s used to being in charge. For every mijo, there is an equal and opposite papi.

114. The Nine

April 24, 2019Nine quarters, says the sign that appears in the middle of Dalton’s pivotal conversation with Wade Garrett, right after he blows off the threat presented by Brad Wesley. Right away we can see that reality has warped a little, that a glitch in the matrix has appeared. As well it might: Dalton has just underestimated his opponent and failed to expect the unexpected, a violation of his own First Rule. And for that, a price must be paid.

But what if there’s more to it than that?

It was not I who set myself on this path, but reader @RoddySwears. It was he who noted the numerological significance of the established price. Nine quarters. Two dollars and twenty-five cents. $2.25. 2 + 2 = 9.

What could such a specific prophecy mean?

Then I realized.

The Nine are abroad.

113. Signs

April 23, 2019Dalton goes to a laundromat to make his phone calls. There’s no phone in his luxury barn, we know this from Emmett’s anti-sales pitch when he rents the place. Either he doesn’t have opening privileges for the Double Deuce or he wasn’t in that part of Jasper (the Auto Parts/Boat Sales/Hellhole district) when he needed to make the call. Either way, here he is, inside this beautiful laundromat that I’m almost positive you couldn’t find somewhere in California in 1989 or thereabouts, reaching out and touching his mentor Wade Garrett. He’s wondering if Wade’s heard anything about a guy named Brad Wesley, because (I’m inferring) any man who’d make trouble for a cooler stands a decent chance of having been watchlisted by veteran cooler agents across the country. Wade comes up empty, though using his cooler-sense he asks Dalton if he’s gotten into any kind of trouble. “Nothing I’m not used to,” he says, before adding with a chuckle “but it’s amazing what you can get used to, isn’t it?” Wade banters back, they say their goodbyes, that’s that.

But look what happens after Dalton says Brad Wesley is nothing he’s not used to.

Suddenly a sign appears where none had been before. The sign lists the cost of using one of the laundromat’s large machines: NINE QUARTERS. I never noticed this until just this afternoon.

So here’s the situation. You can choose to believe this is just the kind of harmless, almost invisible continuity goof that happens in nearly every movie.

Or you can take it as a sign [pause for reader recognition of the awesome implications of the connections being drawn here] that for dismissing Brad Wesley, a price must be paid.

Search your cooler-sense. You know what is true.

059. Men in Black

February 28, 2019When I wrote about Wade Garrett yesterday, I remembered something about his black t-shirt: He’s not the only cooler in the movie to wear one. The other of course is Dalton—but it’s not like he wears it all the time. The movie shows us he’s molded in Wade’s by deploying black in his wardrobe on three key occasions.

Attentive readers of Pain Don’t Hurt will have guessed the first by now: The Giving of the Rules. This takes place prior to Wade’s introduction, directly linking the older man’s debut to the establishment of his acolyte’s doctrine.

The second is the fight that takes place the night he and Doc have their first date, which is also the first time we see him on the job after we meet Wade. This reinforces the sense of succession while also tying Dalton’s romantic flourishing to the older man’s tutelage.

The third is his impromptu breakfast summit with Brad Wesley, during which Wesley brings up his checkered past and offers to hire him away from the Double Deuce. It’s not a t-shirt here but a collared shirt, as befits this more formal occasion. But the dialogue makes direct reference to an event in Dalton’s past that Wade will also bring up (while wearing a collared black shirt himself) later in the movie, and shows Dalton standing up to an asshole in a way that would do his mentor proud—even if he’d likely suggest getting out of Dodge afterwards.

Clothes make the man. Clothes mate the men.

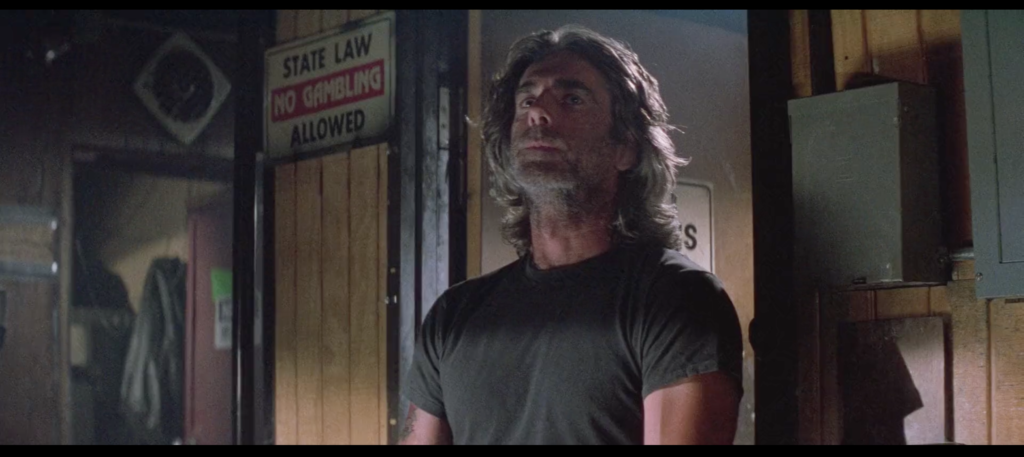

058. The Sentry

February 27, 2019The shadow lies upon Wade Garrett when first we see him. He stands ramrod straight, stiff lipped, chin up, eyes alert. He rocks back and forth from the intensity of the vigilance thrumming in every sinew and synapse. To his right is a sign of prohibition. To his left, a box controlling the generative energy of the bar itself. Behind him, a doorway, barred by his very body. His hair is grey with the knowledge and peril of the long years, and his raiment is black. Wade Garrett knows the gate. Wade Garrett is the gate. Wade Garrett is the key and guardian of the gate.

At that very moment, here’s what he’s looking at.

Not without professional cause, mind you. Within seconds, a horned-up Marine yells “CHARGE!” and rushes the stage, and Wade must rush into action. He sits the jarhead’s ass back down and defuses the situation with a quip about Rambo and saving the world from the Commies that shows Dalton is not the only cooler for whom Be Nice is a cardinal rule. But his protégé, strong though his game may be, could never match the sly grin Wade flashes at the dancer he rescued, who smiles and winks appreciatively in return. Condoms have been lab-tested with less.

What can we learn of the Way of Wade Garrett from this sequence? Most obviously, the integrity of the Wet T-Shirt G-String CONTEST every NITE! would rightfully be called into question but for his presence. We see that humor, even irony, feature prominently in his bouncing arsenal. We see him through the eyes of a dozen drunk, erection-toting members of the United States Marine Corps, who view him as likeable enough, formidable enough, or most likely both to allow him to lay hands on one of their number and walk away unscathed (and bowlegged). He is himself horny, and hairy, but not handsy. He’s quick to action, but not eager for it; not for him is Dalton’s remonstrance to Morgan about not having “the right temperament for the trade.”

And from that first look at him, standing silent sentry in the half light, we see that he harbors within him a darkness—one that does not belie the revelry with which he surrounds himself and the merry manner in which he polices it, but which informs and complements it. He is only at ease because he knows all there is in the world to worry about. Those things have worried at him, and he has held them at bay. For now, anyway. For now.

028. Lebowski (I): Windshields

January 28, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a grizzled gray-haired man with a molasses drawl played by Sam Elliott dispenses wisdom to a practitioner of tai chi who finds himself at odds with a rich, sleazy business magnate with a personal goon squad played by Ben Gazzara. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film about same.

We will be revisiting the Road House/Lebowski Cinematic Universe. Boy, will we! But for now let’s focus on what I like to call The Windshield Shots. In Road House, Wade Garrett has just arrived in Jasper, Missouri to lend a hand to his old running buddy Dalton as the latter wages an increasingly vicious war with Brad Wesley, the film’s Gazzara. After rescuing his ass from a four-on-one beatdown—seriously, they’re just holding him in place and punching him in the gut like he’s a human heavy bag when Wade finally shows up to save the day—Wade goes for a drive in the passenger seat of Dalton’s car, the abuse of which by the angry patrons of the Double Deuce is a running gag, one that runs too far by any reasonable standard in fact. For that reason, riding shotgun puts Wade in an unenviable position.

But look at Wade here. He’s tickled pink! I assume he likes the feel of the wind through his magnificent head of hair, but it’s more than that. We will see, time and time again, how his most dangerous and dirty exploits amuse him, and how the same is true of Dalton’s. Riding through Jasper with a gigantic hole of shattered glass in front of him reassures him that it’s business as usual for his treasured “mijo.” It’s a sign that Dalton’s pissing off all the right people. And since Wade is a firm believer in the cut-and-run strategy when shit gets too heavy, he’s no doubt aware that the car will not long outlive Dalton’s stay in town, however long that may be. “It seems to me you’d be a little more more…philosophical about it,” he says later (much later) that evening, about an entirely different matter. But that hole in the glass, framing his “Aw shit-hell kid, I’m in hog heaven” grin, is already our lens into the Wade Garrett Mindset. He looks at broken things and sees a chance to live a life defined more by parts than the whole they add up to. Moving from one sensation to the next, treating calamity as opportunity, riding the nightlanes, bound only to those who ride with him: That is Wade Garrett. All Dalton can do is grin and bear it. Currently, it is time to be nice.

The Lebowski triarchy is an entirely different matter. Put aside whatever this Windshield Shot does or doesn’t owe to its predecessor. (I certainly believe the Coen Brothers, who after all put Sam Elliott and Ben Gazzara in their movie about a pair of weirdos fending off some rich guys and some goons, had seen Road House, but it’s irrelevant.) Despite sharing the tonsorial sensibilities of Wade Garrett, the Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, is pointedly not enjoying this breezy night drive. There will be no next down for him to head to. His car is not something he can stand to sacrifice. The Dude does not abscond. The Dude abides. He’d prefer to abide with a windshield.

Walter Sobchak occupies the Wade position in the car, but again, the contrast is revealing. No smile for Walter, no “shyush, don’t this beat all” grin. Walter is a man who can never admit that things have not gone according to plan, that every eventuality has not been foreseen and warded against. If at the beginning of the evening he said they would swing by the In-N-Out Burger, then goddammit that’s what they’re doing. If, in the interim, they attempt to brace a teenage boy for money he didn’t steal, vandalize a car he didn’t buy, and antagonize the neighbor who is the real owner of the car until the Dude’s own vehicle winds up getting the worse of it…well, the In-N-Out’s still there, isn’t it? Then he’ll by god buy it and eat it. As he says elsewhere in the film, “I’m staying. I’m finishing my coffee. Enjoying my coffee.” Situation normal, et cetera et cetera. Ironically, only his fellow veteran of American imperialist adventure in East Asia, Brad Wesley, shares this need to control the narrative.

Oh, Donny? Donny’s literally taking a back seat, literally a few steps behind. (Windshield’s out, Dude.) Lacking any physical or intellectual agency, he’s just along for the ride. He has no character in Road House. Unless…unless…

017. The Double Douche

January 17, 2019Dalton has worked at the Double Deuce for a while now, and business is booming. The place is packed every night. The bartenders and bouncers wear jaunty red shirts as uniforms. The band is out from behind the chickenwire. The facade has been remodeled to look like a place the gang from Saved by the Bell might visit. There’s just one problem: Brad Wesley has cut off the liquor supply. Dalton, an excellent cooler but not the most excellent cooler, knows this is no job for one man. He makes a call. (He has sex with the Doc.) Then, as Dalton requested, Wade Garrett arrives. Senpai has noticed him.

Wade Garrett is played by Sam Elliott, and what you’re picturing is almost what you get. The voice is there. The sense that you’re looking at a person who’s more beef jerky than man is there. But this isn’t the fine upstanding cowboy who wishes the Dude wouldn’t use so many cusswords. (Nor even the actual pitchman for beef.) Wade Garrett is a bit dangerous, a bit sleazy, a lot sexy. “Louche” might cover it.

So when Wade Garrett pulls up on his motorcycle, he doesn’t so much dismount the bike as ooze off of it. You can all but hear his bowlegs creak and stretch, smell his two-day post-shower aroma spiked with cigarette smoke and exhaust fumes and hot asphalt, feel him adjust his hips to ensure he’s doglegging in the proper direction within those skinny black jeans.

Wade Garrett looks up at the Giuliani Times Square marquee Frank Tilghman has erected over the former dive bar where young Dalton works, runs his hand over his greasy gray hair, and reads the name aloud: “The Double Douche.” [Sic.]

Why does he pronounce it this way? On one level I assume it’s a tip of the hat to the all-time god-emperor of pronouncing “deuce” as “douche,” Manfred Mann’s Earth Band’s version of the early Bruce Springsteen composition “Blinded by the Light.” Wade does have his shades on, and it is very bright out.

But it’s more than that. It’s a demonstration of Wade’s contempt for anything but the work of cooling itself. You can wrap it up like a Deuce, or a Douche if you will, but beating up the people who beat other people is what he’s here for. No delusions, no pretensions. He came to fight. To quote the man himself when he’s asked “Are you gonna fight, dickless?” a couple minutes later, “I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick.”

And it’s a signal that whatever his affection for his protégé Dalton, he shares little of the younger man’s philosophical outlook. It’s hard to imagine Wade Garrett telling anyone that being called a cocksucker is just “two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response.” Wade is too much of the wild man, too much the heir to Mifune in Seven Samurai. Wade’s world is one of George Carlin’s seven words, several of which he lets fly before his untimely demise. It’s a world of sweat and blood and sexual fluids. Those are things he understands. Those are things he treasures.

This is not to say that Dalton is a slacker in any of those departments—far from it. It’s just that he maintains a certain detachment from it all. Not so Wade. He’ll pull his sidekick’s ass out of the fire one minute and compliment his sidekick’s girlfriend’s ass the next. He’ll show a woman he just met his pubic hair in order to reveal a wound incurred from a previous woman who was presumably well acquainted with his pubic hair before things went south, so to speak.

Speaking of bad breakups, the horrible crime of passion that haunts Dalton? Wade blames the woman whose husband Dalton murdered with his bare hands more than Dalton himself on account of her never revealing her marital status, and sees it as a simple matter of kill or be killed. Yet he’ll expose intense feelings like that only when pushed by the man closest to him, Dalton himself. Otherwise Wade Garrett is, as Billy Joel would put it, quick with a joke or to light up your smoke. He’s still cracking wise the last time we see him alive, after he’s been beaten half to death.

Put succinctly, Wade Garrett the type of guy to ride hundreds of miles to the rescue of his best friend, then make a sophomoric douche joke when he arrives. There are many ways to be an itinerant bouncer-sage in this world. The path of Wade Garrett is but one, as valid as any other.

001. Fame

January 1, 2019 Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

Road House is a film about a very famous bouncer. Not the most famous bouncer; that man is a supporting character. And not technically a “bouncer” either; our hero, played by Patrick Swayze, beautiful and terrible as the dawn, is a cooler, which is to say the Head Bouncer In Charge. But his job is basically bouncing, and he’s so good at it that he’s become famous for it.

So that tells you something about the kind of film Road House is: It respects the people who beat up people who beat up other people in bars so much that it affords them significant renown. Other men will fly across the country and offer these men hundreds of thousands of dollars a year for their services. Barfolk, for want of a better term, whisper their names in reverent awe. In the land of the blockheaded, the two-fisted man is king.

Because their reputations precede them, or because to invoke them inaugurates the ritually contracted cycle of redemptive violence for which they’ve been hired, the bouncers of Road House are reluctant to share their names.

“You got a name?” asks Carrie Ann, waitress at the Double Deuce, the ultraviolent Missouri honky-tonk at the heart of the story. “Yeah,” answers our hero.

“What’s your name, buddy?” asks Pat, the Double Deuce’s thieving failnephew bartender, who is played by John Doe of Los Angles punk institution X. “Coffee, black,” responds our hero.

When he conducts his first official bouncing during his tenure at the Double Deuce by smashing the face of a man with a switchblade and a Hawaiian shirt through a table adjacent to the one on which this man’s girlfriend has been dancing and thus lowering the overall atmosphere of class in the establishment, it falls to our hero’s blind white blues-playing guitarist friend Jeff Healey (appearing as himself) to reveal his identity to the amazed, and in several cases visibly aroused, patrons.

“The name,” he says, “is Dalton.”

Dalton is by this point in the film known to the Double Deuce’s staff, over whom he’s been given absolute authority by the bar’s bizarre owner Frank Tilghman. “What he says? Goes,” Tilghman tells his employees.

“It’s my way or the highway,” Dalton concurs.

The first person to learn his identity other than Tilghman himself is Carrie Ann, who powers through our hero’s extremely badass rebuff as described above and gets him to name himself, the way Superman tricks his gnomish extradimensional enemy Mr. Mxyzptlk into saying his own name backwards to eliminate him. (Carrie Ann has no such goal, of course; it is perhaps for this reason that she is rewarded later in the film with a glimpse of our hero in the nude. to which she reacts with slackjawed lust so powerful, courtesy of actor Kathleen Wilhoite, that it all but glows with its own internal erotic energy.)

“Shit,” Carrie Ann says when Dalton reveals himself. “I heard a’ you!”

The news spreads like wildfire through the waitstaff, bartenders, and bouncers already in the Double Deuce’s employ, none of whom need its import explained to them. Like I said, a famous bouncer’s reputation precedes him. One man has heard he ripped a guy’s throat out with his bare hands. Another has heard he has balls big enough to come in a dump truck. “Sometimes you wanna go where everybody knows your name,” runs the song from another artifact of Eighties bar culture. Dalton can go anywhere.

Which gives us some indication of his exact level of fame. No one at the Double Deuce recognizes him on sight, which means he’s not so famous that his face alone writes his ticket for him. However, the moment he says “Dalton” in response to Carrie Ann’s query, she immediately assumes he is the Dalton famous for being a bouncer, and not any of the other myriad possible Daltons in the world—B. the bookseller, for example. It’s as if she asked a woman who was new to the Double Deuce for her name, and that woman replied “Gaga.” Only one person leaps to mind.

This separates our hero from his hero. “Wade Garrett’s the best,” Dalton tells Tilghman when the Missouri restaurateur says he’s heard he, Dalton, is the best. “Wade Garrett’s getting old,” Tilghman replies. But age has not dimmed his starpower. Arguably, age is responsible for it. The longer he’s been out there, bouncing and cooling, the more time the dive-bar demimonde has had to put a face to the name.

The face belongs to Sam Elliott, who in this film has long greasy hair, tight black jeans, five o’clock shadow that creeps up his face nearly to his eyes, and a grizzled sexuality that wafts from the screen like a musk. When he arrives at the Double Deuce to help his one-time protégé Dalton defend the establishment against the depredations of Brad Wesley, a local business tycoon and J.C. Penney franchisee played by Ben Gazzara (The Killing of a Chinese Bookie), no one asks his name, because no one needs to. Practically the entire staff stares at him with the wide eyes of children in a film directed by Chris Columbus when he limps bowleggedly into the place looking for his mijo.

Grinning slyly, his eyes twinkling with a sinister delight that seems to be actor Kevin Tighe’s natural mien and has no basis within the character itself, Tilghman looks at this man and says, “I know you.”

Wade Garrett, it can be concluded, has achieved a level of fame so total that even people steeped enough in bouncer culture to know Dalton by name know him by sight. Michael Jordan fame. Michael Jackson fame. Santa Claus fame. Wade Garrett is the best, Dalton tells us. And when Dalton speaks, we would do well listen. It’s his way or the highway. What he says? Goes.

Directed by Rowdy Herrington, written by David Lee Henry and Hilary Henkin (Academy Award winner, Wag the Dog), released in 1989, directed by Rowdy Herrington (the name bears repeating), and starring Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, Sam Elliott, Ben Gazzara, and an assortment of people with anywhere between one to six lines of dialogue all of whom I adore completely, Road House is one of my favorite movies ever made. I like to talk about it. I hope you’ll like to listen.