Posts Tagged ‘rambo’

How ‘Last Blood’ Destroys Rambo’s American Myth

September 23, 2019“When you’re pushed,” John Rambo once said, “killing’s as easy as breathing.” In his decades-long career as an action-movie icon, Rambo has been pushed plenty.

In 1982’s First Blood, the traumatized Vietnam vet ran afoul of a small-town sheriff in the Pacific Northwest and proceeded to all but level that town in a quest to simply be left alone. In 1985’s Rambo: First Blood Part II, he was extracted from prison and sent back to Vietnam on a hunt for American POWs, slaughtering Soviet and Vietnamese communists in service of one of the great American right-wing myths. In 1988’s Rambo III he journeyed to Afghanistan to rescue his old mentor from Soviet captivity, and in the process helped the country’s mujahideen fighters make the place Russia’s Vietnam. And in 2008’s inimitable Rambo, he rained death upon a Burmese warlord in order to free missionaries who’d been tending to he needs of the country’s oppressed Karen minority.

And now, in Rambo: Last Blood, he kills some guys who killed his niece.

Directed by Adrian Grünberg from a script he co-wrote with star Sylvester Stallone, Last Blood strips the Rambo franchise of any overt political ideology whatsoever. He’s not on a rescue mission, at least not for long. He’s not fighting for his country, or for some nostalgic, patriotic version thereof. He’s spilling blood because he wants to — because he feels he needs to. It’s all red; no white, no blue.

I wrote about Rambo: Last Blood and how it strips the Rambo myth down to straight-up murder for Thrillist. It’s a sequel of sorts to my piece on the 2008 Rambo film on its tenth anniversary. As a body of work, the Rambo movies—one of two film franchises based on Sylvester Stallone’s idea that watching other men destroy his perfect body is inherently interesting—are so strange and fascinating to me.

187. Stitches

July 6, 2019“Why must a movie be “good” ? Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a beautiful face, huge?” When Mike Ginn wrote this on twitter he could easily have been speaking about Road House, since the beautiful faces of Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, and Sam Elliott are no small part of the attraction and entertainment. (If you find a film studies program that articulates the sensual pleasure of cinema this effectively in two sentences or less, please ask a billionaire to give it a grant.) But in the action films of the 1980s—as in many other genres and many other time periods, but here the tendency is especially marked—there’s another question to ask: Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a beautiful face, bruised?

Sylvester Stallone is one of the strangest extremely famous and mainstream people in Hollywood. I often think of the road not taken when he put out Rocky II and thus gave the lie to the final exchange between Rocky Balboa and Apollo Creed about rematches in the first Rocky film, which would otherwise be remembered as the classic of 1970s New Hollywood that it actually is. But since he is often not just the star of his films but the writer and/or director as well, his idiosyncracies shine through in even the most fast-food slop he serves up. Regardless of how slick, bombastic, and ultimately jingoistic the Rocky and Rambo series wound up getting by the end of the ’80s, in direct opposition to the earthy, low-key, and questioning debuts, they are at heart two separate franchises created by Sylvester Stallone based on the assumption that watching his perfect body get destroyed over and over again was crackerjack mass entertainment. That he was correct speaks to a desire in the audience to see that which we desire abased and laid low. Kink has understood and articulated this forever; cinema can’t really speak it aloud, but it’s there alright.

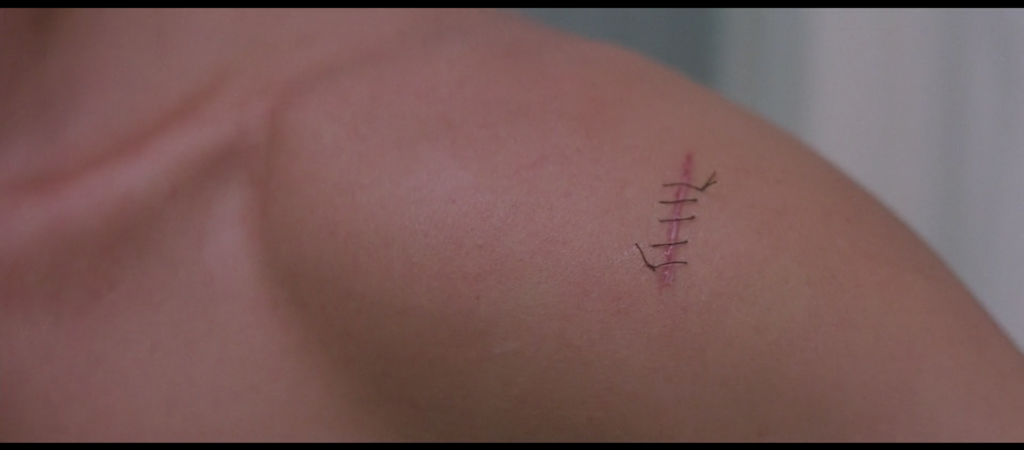

As I was flipping through my copy of Road House, which is often what I do to start this daily process, I stumbled across this frame of Patrick Swayze’s shoulder with a stitched-wound makeup effect stemming from Dalton mending the knife injury he incurred at the start of the film. At no point does Dalton take a beating that John Rambo and Rocky Balboa would even recognize as such. Yet because of his lithe dancer’s physique (“I thought you’d be…bigger”), the delicacy of his movements, and the coded-feminized prettiness of his face and hair, we feel the shit out of every punch and kick and cut. His penultimate battle, with Jimmy, is to my mind one of the best fight scenes ever filmed not just because of the ace choreography and Swayze’s and Marshall Teague’s almost dangerous commitment to the scene (they realized after the first night of filming that they’d have to pull some more punches if they wanted to successfully complete the damn movie), but because of how Swayze’s shirtless, glistening, fire-illuminated torso radiates physical beauty even as it’s getting pummeled into hamburger. The beating is the spice that brings out the flavor of the dish. So too here with the wound and the stitches, six bold slashes through an unblemished field of bare smooth flesh. The stitches could just as well spell “Kiss it and make it better.” So could the Hollywood sign.

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 73!

March 30, 2018Starship Troopers and Rambo

Come one, you apes! You wanna live forever? We sure hope not, because when you’re pushed, killing’s as easy as breathing. And so is listening to Sean and Stefan discus two of the most violent — and morally complex — action movies of the modern era, Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers and Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo. Made in 1997 and 2008 respectively, these films use satire (in the former case) and spectacle (in the latter) to probe the gaping wounds of fascism, war, war movies, and the act of killing. If, like us, you’re an admirer of how A Song of Ice and Fire and Game of Thrones use epic-battle tropes to interrogate the horrors of war, this discussion of two strange films that do the same is for you. Enjoy…?

Additional links:

Stefan’s essay on Starship Troopers (Patreon subscribers only).

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour.

Our PayPal donation page (also accessible via boiledleather.com).

Stallone’s ‘Rambo’: The Strangest Sequel Ever Made

March 5, 2018John Rambo spent the 1980s knifing, booby-trapping, and exploding his way into the American consciousness. But to resurrect this killer of a character for the 2000s, Sylvester Stallone dug deep into the heart of his hero… and dear God, that heart was dark.

Released in early 2008 to solid box-office success and minimal critical favor, Rambo promised a back-to-basics approach to Stallone’s hit action franchise, just as 2006’s acclaimed, heartwarming Rocky Balboa had done for The Italian Stallion. Stallone even planned to title the movie John Rambo to make the comparison even more direct, and wound up using that title for the film’s longer, more character-driven extended cut. But while the fourth and final film in the Rambo franchise gave Sly’s troubled Vietnam veteran a happy ending at last — its closing shot shows the 60-year-old killing machine returning to his family farm in Arizona for the first time in decades — it also gives us a character to fear, not root for. This evolution of Rambo as a character and mainstream action franchise, in turn, reveals uncomfortable, disturbing truths about the United States, and after a recent revisit, suggests that our own violent history should be treated with far more nuance than unquestioned cheerleading.

Set in the killing fields of Burma, Rambo is a brutal and bracing revisionist take on a hero whose name is synonymous with mindless action-movie excess, from the man who helped craft that excess in the first place. Yet it’s precisely because of its unprecedented savagery that the film feels truer to John Rambo’s roots than either of the sequels that preceded it: the movie, this time directed by Stallone, takes the philosophical tensions and fear of warfare present in the franchise since its politically fraught initial installment, loads them into a machine gun, and fires them directly at our collective face. Using all the tools at an old Hollywood hand’s disposal, it reflects the national mood by depicting its angry American as both suffering and inflicting trauma, in as traumatizing a manner as big-budget action movies have ever attempted.

Three thousand words on Rambo for Thrillist? Don’t mind as I do. I’m proud of this piece on one of the most viscerally disturbing and structurally odd mainstream action movies ever made.