Posts Tagged ‘Peter Jackson’

160. How to Build a Better Goon

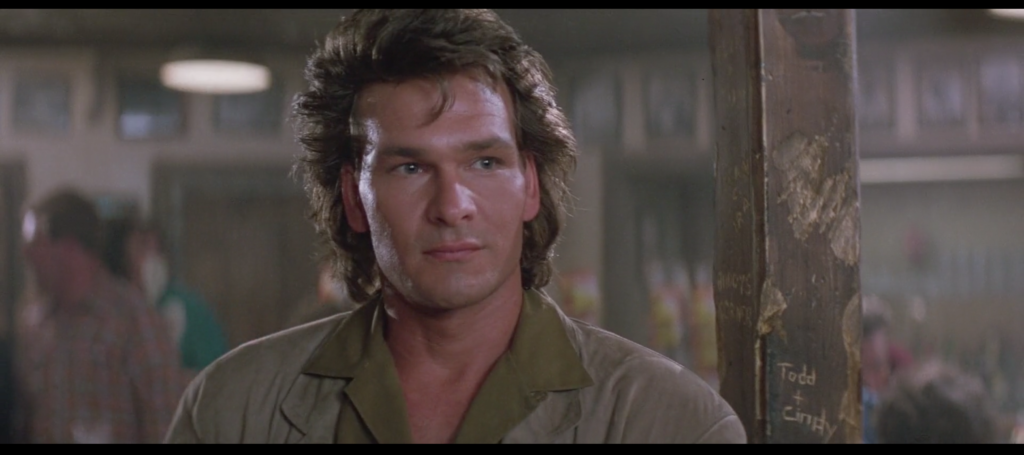

June 9, 2019Ketchum is a forgettable goon. That’s just facts. I know who he is because I’ve watched Road House a million times, and you know who he is because you’re reading this series of daily essays about Road House. But it took me a long, long time, and many, many viewings, to put Ketchum together, as it were: that he drives the monster truck any time it shows up; that he’s the guy who tries to kick Dalton in the head with the knife in his boot and gets his ass kicked instead; that he’s the man who kills Wade Garrett, as evidenced by his retrieval of the knife used to kill him and insertion of that knife into a custom sheath on his hip; that he’s the last goon to tangle with Dalton hand to hand; that his name is Ketchum.

Alone among the goons present for the climax of the film, no one even says his name in the movie, a privilege afforded to Pat McGurn, Morgan, O’Connor, Tinker, and Jimmy. I’ve made a fuss about this over the past few months, alleging that it’s one of the reasons he’s so forgettable. But I’ve been thinking about that assertion lately, because I don’t think it has to be that way.

Consider the orcs.

Remember these handsome fellas? Sure you do. That’s Lurtz, Grishnakh, and Gothmog, from Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. No one says their names in the movies. No one says any orc’s name in the movies. For that matter, Lurtz is a made-up name for a brand-new character the filmmakers introduced, and Gothmog is simply their best guess as to what a Mordor commander from the books whose species isn’t even specified by Tolkien might be like.

But if you’ve watched those movies recently, or if you find them memorable at all, you probably recall them as the uruk-hai leader with the Ariana Grande hairstyle whose head gets chopped off by Aragorn after a big fight, the raspy-voiced weasel who tries to hunt and kill Merry and Pippin before Treebeard squishes him, and the leader of the orc assault on Minas Tirith with the big puffy pink face. You remember how they look, how they sound, and what they do, because Jackson and company made a big point of giving them memorable introductions, isolating them with distinct camerawork (closeups, angles, whatever the case), and having them do their most memorable stuff right there for all to see. Lurtz was created to give the uruk-hai chasing the Fellowship a distinctive leadership figure so the film’s climax would work as such. It’s a far cry from the aggressively nondescript Ketchum first showing up as a non-speaking background character wearing face-masking sunglasses during the Bleeder scene and eventually killing Road House‘s secondary protagonist off-screen.

For that matter, it’s a far cry from these fellows.

Karpis and Mountain are also never named. They’re only shown in close-up in couple of scenes apiece; in Mountain’s case, one of those scenes is a pool party (in which Karpis appears in the background). Neither of them make it to the film’s final reel but it’s not because they get killed—they simply stop showing up, because that’s how Road House rolls.

But you remember them, right? They each have a distinctive look, with Karpis’s clothes from the Bun E. Carlos collection and Mountain’s sheer size. They each do something interesting: Karpis stares down Dalton, and Mountain dances like an idiot and later Sam Elliott tells him “I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick” before taking him down. The camera makes a point of both of them: Karpis stares right into it in closeup, while Mountain becomes the focal point as it follows Wesley and Denise into the pool party.

When it comes to differentiating your goons, bothering to say their name during the film helps, especially if you name half a dozen comparable characters during the film and run the risk of drowning the unnamed one out. (That doesn’t apply to LotR.) But you need the look, you need a distinctive action, and you need a memorable trick with the camera to make the look and the action click in the viewer’s mind. It’s a bit unfair to compare Rowdy Herrington’s work with Ketchum to Peter Jackson’s work in The Lord of the Rings, which is better at this than any other film I’ve ever seen. My point is simply, what’s in a name?

080. Dodge

March 21, 2019

If there’s anything else in the history of action cinema I’ve studied with the same open-hearted intensity I’ve applied to Road House, it’s the Tomb of Balin/Bridge of Khazad-dûm sequence from Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Back in the summer of 2001, in the Before Times, I was invited by New Line Cinema in my capacity as assistant editor of the Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly, my first real job out of college (see what I mean about the Before Times?) to watch the 20 minutes or so of footage from Jackson’s first Lord of the Rings movie that had been publicly screened, initially some weeks prior at the Cannes Film Festival. Wisely the studio had selected the film’s first real action setpiece, the slobberknocker with the orcs and the cave troll in Balin’s Tomb and the flight down the crumbling staircase afterwards. Any doubts I might have harbored about the ability of Jackson, a filmmaker whom I loved for Heavenly Creatures but wasn’t sure could tamp down his manic style for Tolkien’s world, evaporated the moment the fighting began. This was a director who understood that effective action is shaped by the environment in which it’s staged, with easily understandable physical stakes for the success and failure of each blow and maneuver, relayed through camerawork that allows the eye to parse the spatial relationships between the combatants.

What’s more, and the friend I brought along with me as my plus-one to the screening room is the one who pointed this out, Jackson understood that the key to fantasy as a genre is scale, intuiting George R.R. Martin’s much-quoted dictum that we turn to fantasy “to find the colors again,” to transcend drab reality on (paraphrasing here) the wings of Icarus rather than Southwest Airlines. Neither Jackson nor Martin (nor Tolkien, nor Benioff & Weiss for that matter) felt this meant completely detaching the material from reality; on the contrary, the punishing realism of Martin’s setting and the painstaking detail of the Weta Workshop’s worldbuilding made the truly massive scope of the landmarks and lives of Westeros and Middle-earth all the more convincing.

I’ve told this story many times now, but it was specifically one of the Moria sequence’s action beats that brought this home to me. As the Fellowship flees down those gigantic, precarious stairs, orcs begin pelting them with arrows. Legolas, the Elven archer, turns and fires back at one of the distant foes. The camera travels as if mounted on the shaft, giving us an arrow’s eye view of the cave and the evil creature on the opposite end towards whom it is racing. A cut at the moment of impact switches us to a view of the same cavern from just behind and above the orc (by now struck right between the eyes and plummeting into the abyss below), angled downward toward the Fellowship on the stairs hundreds of yards away. The arrow’s flight, and our flight along with it, describes that vast space in a way a more traditional establishing shot could not. If we’d started with that over-the-shoulder shot looking down at the Fellowship we’d have gotten the picture I suppose, but we wouldn’t have been made to feel the space, the scale, the awe.

Whether to reserve the sight of the Balrog for the eventual filmgoing public or because that sight had not yet been completed I can’t recall, but the preview cut off with our final glimpse of the Fellowship escaping the stairs. The chase across the Bridge, the standoff between Gandalf and the Balrog, Gandalf’s triumph and fall, and the Fellowship’s mournful escape had to wait until the premiere. But there’s another moment with an arrow that stuck with me then and still does today. As Aragorn, the last one out of the Mines, looks back at the chasm, the rain of arrows from the orcs, who’d given the Balrog a wide berth, resumes. Viggo Mortensen, an amazing proficient action performer for a guy who had about a week of instruction before his first on-camera swordfight compared to the rest of the cast’s extensive training camp, had clearly been instructed by Jackson to act as though he was dodging arrows that were added digitally after the fact. Like a particularly generous pro wrestler he sold the hell out of it, at one point ducking so dramatically it’s like he was avoiding some big galoot’s haymaker. The desultory choreography of the move jumps out at me because Mortensen’s Aragorn is otherwise a model of physical efficiency in his fighting style, as befits a man who’s been hunted all his life and has learned that excess movement can mean the difference from ending a fight merely exhausted and ending a fight dead. It’s taken me time to come around to it but I now recognize it as the right approach for a character who’s been momentarily poleaxed by a grief he never believed he’d experience.

Anyway, at one point during the big bar-destroying fight that breaks out in Road House when a man squeezes another man’s wife’s tits without paying to kiss them as he’d appeared to agree to do, a stray bottle comes flying in Dalton’s direction and shatters against the post next to which he’s been standing and taking in the scene, and he dodges it and resumes watching in less time than it took either of the arrows described above to do their thing. This doesn’t tell us anything about the scale of the Double Deuce, the spatial relationship between Dalton and the unseen bottle-thrower, the nature of the world in which the film takes place, the emotional state of the characters, or the approach of director Rowdy Herrington toward the material. It just tells us that Dalton is so good at dodging broken glass that it doesn’t even disturb his spit-curl. And that’s all you need to know, son.

The arrow that made me love The Lord of the Rings

June 26, 2014On my A Song of Ice and Fire tumblr boiledleather.com the other day, a reader asked me:

I’m sure that someone has asked this before, but what are your thoughts on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings-adaptations? Especially compared to Game of Thrones (different medium, I know, but still).

In May of 2001 I received an invitation through my job as associate editor of the A&F Quarterly (“the lifestyle publication” of Abercrombie & Fitch) to a screening of the 20 minutes or so of footage of the then-unreleased The Fellowship of the Ring that had screened at Cannes. This was from the Mines of Moria sequence — the discovery of Balin’s tomb, the fight with the cave troll, and the flight down the stairs. It was obviously crackerjack action filmmaking, but I’ll tell you what really hit me the hardest. As the Fellowship flees down that first flight of stairs, orc arrows start raining down on them, bouncing off the stone steps. Legolas turns and returns fire, and the camera gives us an arrow’s-eye-view of its flight across the chasm and into the forehead of an orc archer. At the moment of impact the camera cuts to a shot just above and behind the orc’s shoulder as he falls from his perch into the pit below, and suddenly we can see the enormous distance we’d just traveled on the head of that arrow. Fresh from film school as I was, I was blown away by this. Peter Jackson had used the flight of the arrow to describe the space it was shot in, using its physical movement to convey a sense of scale to us that would not have been possible if he’d simply cut back and forth between the vantage points. This of course is what all action sequences in visual media ought to do — root you in an environment, use the action beats to move you around in that environment, give as many beats as possible palpable physical stakes you can grasp and contextualize immediately. It also showed that Jackson was going to use the full force of the cinematic medium to tell this story — he wasn’t just going to line up a bunch of CGI critters and throw them at one another, nor was he going to whirl and twirl haphazardly, he was going to paint the story with the camera and the editing bay like brushes. It showed that the soon-to-be-legendary attention to detail he and the Weta team paid to every prop and set and costume had a storytelling purpose as well, that a bow and arrow and a stone chasm and a hero-orc makeup job would not just look cool but help us understand where we were and what kind of world it was and why it mattered. Finally, it showed that for the first time ever, a fantasy film was actually going to capture the scale of epic fantasy, the sheer physical awe-someness of it all above and beyond the striking images that plenty of fantasy films before it had dealt in without that ability to convincingly situate them in a world as large as our imaginations. Not a single moment in the entire trilogy contradicted these initial impressions. They’re magnificent films and I love them to pieces.

Movie Time: The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug and The Wolf of Wall Street

December 27, 2013There’s an invented scene in Peter Jackson’s second Hobbit movie (SPOILER ALERT, I GUESS) where Thorin & Company fire up the forges of the Lonely Mountain while dodging an awoken and enraged Smaug the Golden. River-like torrents of molten gold pour into a mold of (presumably) Durin, the ur-Dwarf, that’s about the size of a medium-sized office building. Smaug stares at it enraptured until the heat causes it to break form and gush golden death all over the dragon. Wealth, weaponized. Find all the metaphors for a three-film Hobbit adaptation you like in that scene, go ahead, knock yourself out. Certainly this film’s herky-jerky rhythm, and its need to surround every emotional turning point with an invented ten-minute action sequence, will give you plenty of fuel for the fire. But ultimately Smaug rises again from that lake of fire, bellows a mockery of the Dwarves’ attempt at revenge, flies up into the night sky gilded with real actual gold, shakes it off into a million droplets like a sheepdog drying off after a bath, and flies off toward Laketown to burn it to ashes while shrieking “I AM DEATH.” If I get to see something like that at the movies, Peter Jackson can melt down all the rivers of gold he wants.

Wolf was more fun than Good, and I say that as someone whose favorite Martin Scorsese movie is Casino. One of the reasons it feels a bit light in the end is that we never meet any victims of the penny-stock scams at the heart of the thing, just the scammers and their trials and tribulations. In a sense, that’s Scorsese’s approach with GoodFellas and Casino as well, but in those films the characters frequently turn on and kill each other, so you’re made to understand that the criminality has real-life consequences even if only on other criminals. You see victims; they just happen to be the victimizers as well. This, on the other hand, is just DiCaprio and Jonah Hill being really funny for three hours, with tons of naked women and quaaludes. Which I liked, don’t get me wrong, but it’s almost like Scorsese and Terence Winter (Boardwalk Empire impresario, hence a couple of notable BE castmember cameos) went out of their way to reduce the working-class schlubs DiCaprio and his merry men and women stiff to disembodied voices on phones. (EDITED TO ADD: The major exceptions are Belfort’s toddler daughter, whom his inebriated behavior terrorizes, and his second wife, whom at his nadir he physically and sexually assaults; but the rhythm of the sequence in which that occurs is such that its impact is diluted first by her turning her own rape into a way to best and humiliate her husband, then by a transference of Belfort’s threat from her to the kid. Moreover she’s portrayed as so slight a person — no Karen Hill, no Ginger Rothstein — that it’s weirdly unclear how much she’s ultimately fazed by it.) Still, as I said, really funny. A lot of it is a love letter to the grossness of Long Island, which I enjoyed, and of course the idea of just doing a one-to-one transfer of his mafia-movie style and story structure over to Wall Street is scathing and hilarious. Rob Reiner’s introductory scene had me convulsing with laughter, which I’d forgotten is a thing. Jon Bernthal erases the stink of The Walking Dead every second he’s on screen, so wholly does he commit to his ridiculous Jewish-goombah drug-dealer character. There are close-ups of Hill’s face, and an entire ‘lude-dosed fight scene, that could have come straight out of Tim & Eric’s Billion-Dollar Movie. It’s a pleasure to see Scorsese work with DiCaprio in full charismatic movie-star mode versus the aging-babyface anger he forefronted in, say, Gangs of New York and The Departed. And he’s making an argument that the best sociopaths extend their little reality bubble outward to a few trusted associates — do that and you can get away with almost literally anything. Wolves hunt best in packs.

13 Things You Need to Know About “The Hobbit”

December 13, 2012I wrote a quick-and-dirty guide to The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey for Rolling Stone. Between the source material, the adaptation process, the original Lord of the Rings trilogy, the new 48fps 3D technology, the expansion into a new trilogy, and just generally trying to make a good movie, there’s a ton of stuff going on when you watch this thing, and this piece was my attempt to make sense of it all for everyone before they hit the theater—what to watch for and pay attention to and ignore.

The movie is awesome, by the way. Lord of the Rings Season Two. Anyone who tells you otherwise hates joy. Does anybody remember laughter?