Posts Tagged ‘j.r.r. tolkien’

“The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power” thoughts, Season One, Episode Six: “Udûn”

September 30, 2022As it turns out, Adar’s whole deal is absolutely fascinating: He is a first-generation orc, one of the original Elves whom Morgoth tortured and warped to create his race of minions. (He also claims that he killed Sauron, which, okay buddy, but that’s neither here nor there.) If you’re deep into Tolkien lore — as, presumably, a decent chunk of the audience for a show set in Tolkien’s Second Age would be — this is a glimpse of something we’ve never seen before but have been wondering about since…well, in my case, since I first read The Hobbit at age four. Wouldn’t it have been so much more interesting for the show to make his origin clear immediately, thus getting the audience invested in who he is rather than who he might be, instead of erroneously presuming that mYsTeRiEs are the be-all and end-all of fantasy narratives?

Please recall that there are approximately zero “mysteries” in Tolkien’s work: Aside from the origin of Gollum and the Necromancer, which are irrelevant when they first show up in the text, everything you need to know is spelled out almost immediately, with Tolkien counting on his inventive skill to engross you all by itself. Which it does!

I reviewed this week’s episode of The Rings of Power for Decider.

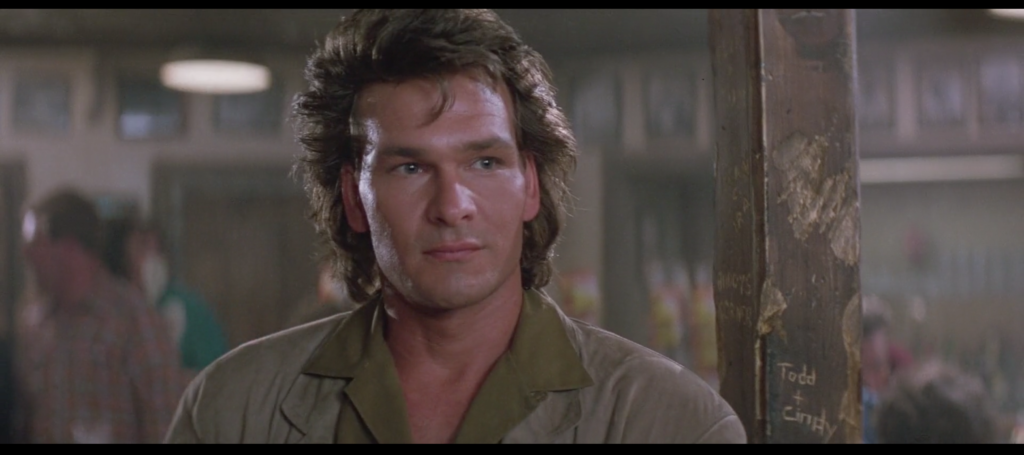

147. Look Back in Anger

May 27, 2019In addition to “embedding a knife in a boot” and “murdering Wade Garrett” and “being Mister Clean Jeans,” Ketchum has a leg up (wink!) on his fellow goons in one other respect: He is outraged that Dalton has the temerity to whip his ass. “Son of a bitch!” he shouts at the cooler as Captain Turner pulls him away, one boot on, one boot somewhere above the streets of Jasper. It’s the same verbiage employed by Carrie Ann when she brains some drunken dipstick with a beer bottle in the middle of that full-scale riot within the bar earlier in the film. She’s just a working woman trying to make a living and not get groped or punched or forced to bear witness to other people enduring the same. Ketchum is a paid killer who just attempted to murder a man by kicking him in the skull with a knife-shoe. That man intercepted the killing Rockette maneuver and simply followed the Three Simple Rules in response. But does this keep Ketchum from acting like he’s the wronged party once things don’t go the way he wants them to? Heavens no. Not one for simply going quietly and licking his wounds is Ketchum. One last “how dare you sir,” in modern vernacular of course, is required before he drifts away, allowing Dalton to go on a date with Dr. Elizabeth Clay that will change the lives of all three of them. (Death changes your life.) In Ketchum’s climactic whinge you hear the sound of privilege. Like his boss Brad Wesley, who expresses surprise that anyone would resist him more than once as the film continues, Ketchum does not believe those he oppresses have the right to fight back. But it’s more than that: He does not believe that those he oppresses should even be able to formulate the knowledge, desire, and will the very notion of “fighting back” requires. They should be as blissfully unaware of their power in this situation as an animal that has briefly slipped loose of its bonds and, should it realize its chance for freedom is upon it, could reduce its human handler to red wreckage. But they don’t realize. Neither, according to the only form of morality the Wesleys and Ketchums acknowledge, should the hoi polloi of Jasper.

J.R.R. Tolkien once said “I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’; but the one resides within the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed dominion of the author” and I think about that a lot.

080. Dodge

March 21, 2019

If there’s anything else in the history of action cinema I’ve studied with the same open-hearted intensity I’ve applied to Road House, it’s the Tomb of Balin/Bridge of Khazad-dûm sequence from Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Back in the summer of 2001, in the Before Times, I was invited by New Line Cinema in my capacity as assistant editor of the Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly, my first real job out of college (see what I mean about the Before Times?) to watch the 20 minutes or so of footage from Jackson’s first Lord of the Rings movie that had been publicly screened, initially some weeks prior at the Cannes Film Festival. Wisely the studio had selected the film’s first real action setpiece, the slobberknocker with the orcs and the cave troll in Balin’s Tomb and the flight down the crumbling staircase afterwards. Any doubts I might have harbored about the ability of Jackson, a filmmaker whom I loved for Heavenly Creatures but wasn’t sure could tamp down his manic style for Tolkien’s world, evaporated the moment the fighting began. This was a director who understood that effective action is shaped by the environment in which it’s staged, with easily understandable physical stakes for the success and failure of each blow and maneuver, relayed through camerawork that allows the eye to parse the spatial relationships between the combatants.

What’s more, and the friend I brought along with me as my plus-one to the screening room is the one who pointed this out, Jackson understood that the key to fantasy as a genre is scale, intuiting George R.R. Martin’s much-quoted dictum that we turn to fantasy “to find the colors again,” to transcend drab reality on (paraphrasing here) the wings of Icarus rather than Southwest Airlines. Neither Jackson nor Martin (nor Tolkien, nor Benioff & Weiss for that matter) felt this meant completely detaching the material from reality; on the contrary, the punishing realism of Martin’s setting and the painstaking detail of the Weta Workshop’s worldbuilding made the truly massive scope of the landmarks and lives of Westeros and Middle-earth all the more convincing.

I’ve told this story many times now, but it was specifically one of the Moria sequence’s action beats that brought this home to me. As the Fellowship flees down those gigantic, precarious stairs, orcs begin pelting them with arrows. Legolas, the Elven archer, turns and fires back at one of the distant foes. The camera travels as if mounted on the shaft, giving us an arrow’s eye view of the cave and the evil creature on the opposite end towards whom it is racing. A cut at the moment of impact switches us to a view of the same cavern from just behind and above the orc (by now struck right between the eyes and plummeting into the abyss below), angled downward toward the Fellowship on the stairs hundreds of yards away. The arrow’s flight, and our flight along with it, describes that vast space in a way a more traditional establishing shot could not. If we’d started with that over-the-shoulder shot looking down at the Fellowship we’d have gotten the picture I suppose, but we wouldn’t have been made to feel the space, the scale, the awe.

Whether to reserve the sight of the Balrog for the eventual filmgoing public or because that sight had not yet been completed I can’t recall, but the preview cut off with our final glimpse of the Fellowship escaping the stairs. The chase across the Bridge, the standoff between Gandalf and the Balrog, Gandalf’s triumph and fall, and the Fellowship’s mournful escape had to wait until the premiere. But there’s another moment with an arrow that stuck with me then and still does today. As Aragorn, the last one out of the Mines, looks back at the chasm, the rain of arrows from the orcs, who’d given the Balrog a wide berth, resumes. Viggo Mortensen, an amazing proficient action performer for a guy who had about a week of instruction before his first on-camera swordfight compared to the rest of the cast’s extensive training camp, had clearly been instructed by Jackson to act as though he was dodging arrows that were added digitally after the fact. Like a particularly generous pro wrestler he sold the hell out of it, at one point ducking so dramatically it’s like he was avoiding some big galoot’s haymaker. The desultory choreography of the move jumps out at me because Mortensen’s Aragorn is otherwise a model of physical efficiency in his fighting style, as befits a man who’s been hunted all his life and has learned that excess movement can mean the difference from ending a fight merely exhausted and ending a fight dead. It’s taken me time to come around to it but I now recognize it as the right approach for a character who’s been momentarily poleaxed by a grief he never believed he’d experience.

Anyway, at one point during the big bar-destroying fight that breaks out in Road House when a man squeezes another man’s wife’s tits without paying to kiss them as he’d appeared to agree to do, a stray bottle comes flying in Dalton’s direction and shatters against the post next to which he’s been standing and taking in the scene, and he dodges it and resumes watching in less time than it took either of the arrows described above to do their thing. This doesn’t tell us anything about the scale of the Double Deuce, the spatial relationship between Dalton and the unseen bottle-thrower, the nature of the world in which the film takes place, the emotional state of the characters, or the approach of director Rowdy Herrington toward the material. It just tells us that Dalton is so good at dodging broken glass that it doesn’t even disturb his spit-curl. And that’s all you need to know, son.

030. “My only sister’s son”

January 30, 2019“I name Éomer my sister-son to be my heir.”—Théoden, The Lord of the Rings

“He’s my only sister’s son, and if he doesn’t have me, who’s he got?”—Brad Wesley, Road House

Not even I, a person with the White Tree of Gondor tattooed on my arm who is writing an essay about Road House every day for a year, can come up with much of a connection between the King of Rohan and the Chief Job Creator of Jasper, Missouri beyond the antiquated syntax with which they refer to their nephews, Éomer son of Éomund and Pat McGurn respectively. Wesley isn’t about to name his mustachioed kinsman his successor anytime soon, certainly. “Pat’s got a weak constitution, you boys know that,” he tells his assembled henchmen after two of their number, Tinker and O’Connor, failed to forcibly reinstate Pat in his old gig at the Double Deuce during one of the Knife Nerd incidents. “That’s why he’s working as a bartender.” Poor Pat, not even fit for full-time goonmanship.

Pat isn’t even present to hear this condescension, having slunk shamefacedly into Uncle Brad’s mansion at the first opportunity, allowing his comrades-in-goon to take the heat. Why should he bother sticking around? He knows his place, and it’s not at his uncle’s side. It’s Jimmy, Wesley’s strong right hand and, in my considered opinion, secret bastard son who’s the heir apparent. “I should have let you go, Jimmy,” Wesley says regarding the failed mission, an avuncular (fatherly?) hand on the back of the younger man’s neck. Better for Pat to spare himself the sight.

So no, Wesley’s rhetorical style here doesn’t remind me of Théoden King. Rather, I’m put in mind of another great man.

Jack Lipnick is the head of Capitol Pictures, the studio that hires a certain New York playwright to give a Wallace Beery wrestling picture That Barton Fink Feeling. Like Brad Wesley, he came up the hard way (“I mean, I’m from New York myself. Well, Minsk, if you wanna go all the way back—which we won’t, if you don’t mind, and I ain’t asking”) and rose to prominence and power by exerting control over the local economy, largely by screwing other business owners out of their share (regarding his assistant Lou Breeze: “Used to have shares in the company. Ownership interest. Got bought out in the Twenties. Muscled out, according to some. Hell, according to me”).

The tone Lipnick adopts when speaking about producer Ben Geisler, whom he fires instead of Barton when the latter screws up, sounds familiar. “That man had a heart as big as the all outdoors, and you fucked him!” he says, voice soaring as if with the eagles as he describes the generosity of spirit found in a guy he shitcanned, then cracking like a whip as he drops the f-bomb on the person truly at fault, at least in his eyes.

Though he prefers physical assault to firings, Brad Wesley reacts in similar fashion over his sister-son’s plight, arbitrarily beating his goon O’Connor unconscious for, alternately, being untruthful, unable to admit he was wrong, weak, unable to tolerate pain, cowardly and above all prone to bleeding. O’Connor’s failure regarding Pat may have occasioned the beating, but it isn’t even mentioned during the beating itself as one of Wesley’s half-dozen reasons for inflicting it.

For men like Wesley and Lipnick, people are worth caring about only to the extent that doing so, or pretending to do so, enables them to torment others on their nominal behalf. These men, like their words, are overinflated and empty. The overwrought sentiment intended to conceal the lie reveals it instead.

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 63!

May 31, 2017BLAH 63 | Our Favorite Fantasies

“What other fantasy books do you like?” It’s one of our most frequently asked questions, and in this month’s episode of the Boiled Leather Audio Hour, we’re answering it? Sean and Stefan tackle the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, R.A. Salvatore, Lloyd Alexander, Ursula K. Le Guin, Susan Cooper, David Gemmell, and Robert E. Howard (with detours into Dungeons & Dragons and H.P. Lovecraft) in a wide-ranging discussion about the fantasy authors and series that they enjoyed as kids, as grown-ups, or both, and what (if anything) separates one from the other. This is a fun one, if we may be so bold. Enjoy!

Additional links:

Sean’s guest appearance on the Delete Your Account podcast with Kumars Salehi.

Our Patreon page at patreon.com/boiledleatheraudiohour.

Our PayPal donation page (also accessible via boiledleather.com).

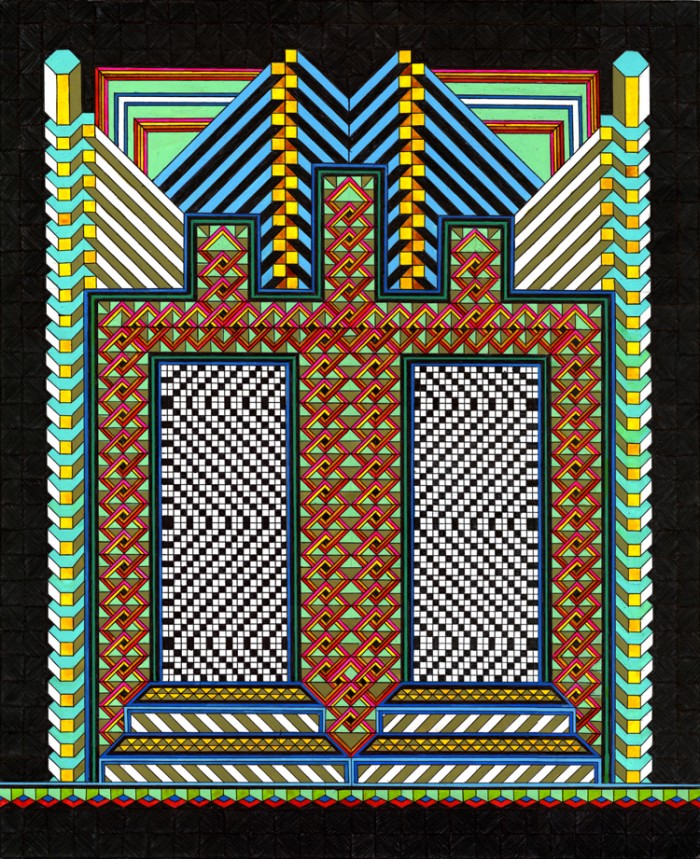

Friday night with Vorpalizer

June 7, 2013Over the past couple of weeks I’ve written about Memory Palaces by Edie Fake, “The Sea-Bell, or Frodo’s Dreme” by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Ghoul Man” by Jaime Hernandez, and “The Cask of Amontillado” by Edgar Allan Poe for Vorpalizer. Check them out.