Posts Tagged ‘fight scenes’

087. Jack

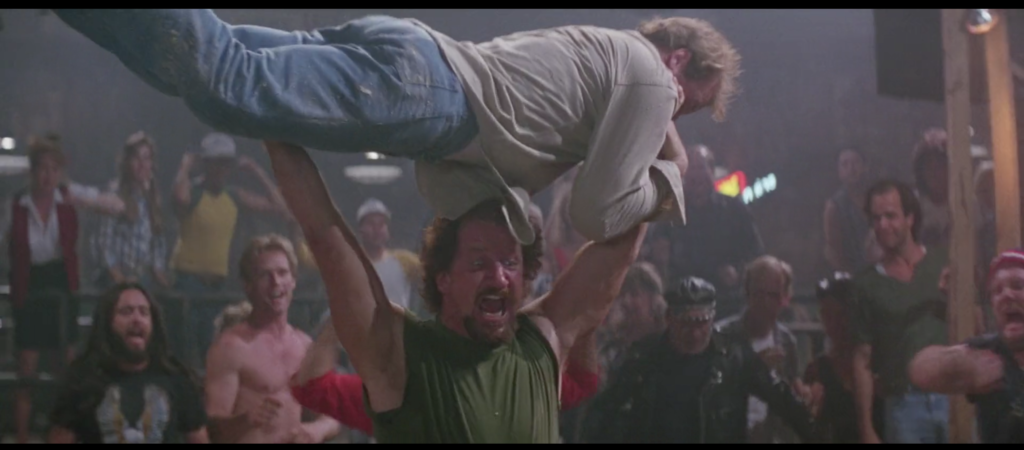

March 28, 2019As we near the century mark here at Pain Don’t Hurt, faithful readers will not be surprised to hear me sing the praises of Jack once again. It’s my growing conviction that Road House may be viewed as the origin story of the heir to the cooler’s mantle possessed by Wade Garrett and passed on to Dalton, and that heir is the man above. Why? Because in less than a second after that image, he is also the man below.

Jack goes 0 to 100 real quick.

As well he should! Here, he is reacting to Sharing Husband’s punch and shove of Gawker into Morgan and the entire crowded bar full of patrons. Jack knows the Double Deuce generally and Morgan specifically well enough to know that all hell is about to break loose, and he knows his own trade well enough to know it’s on him to stem the blood-drenched tide. He does so with sufficient alacrity to send the stool on which he’d been sitting skittering halfway down the hall behind him. The dude’s like the Flash, for real. He’s even wearing red. This is the first time we see him spring into action, but as we’ve learned, it is not the last.

The bouncers of the Double Deuce are not a promising lot when Dalton first arrives to take charge of them. Hank is too timid. Steve is too horny. Morgan should by rights be not the bouncer but the bounced. Younger is…present. Jack, though? In A Song of Ice and Fire he would be referred to as the true steel, supple as needed, able to be honed, unbreakable when it matters. Jesus Christ would recognize him as the good ground, bringing forth fruit an hundredfold. It is toward that good ground that the Way of Wade Garrett and the Dalton Path lead. Beyond? The undiscovered country.

083. Table spot

March 24, 2019DALTON: Morgan, you’re outta here.

MORGAN: …what the fuck you talking about?

DALTON: You don’t have the right temperament for the trade.

Hard to argue with that, huh? As a bouncer, Morgan does not seem to have specialized or differentiated his skill set from that which he applies to his parallel career as a Brad Wesley goon. The nominal purpose shifts from “protect the business interests of Brad Wesley” to “protect the peaceful atmosphere of the Double Deuce,” but insfoar as he simply ports the methods of the former to the latter, he’s doing far more harm than good. The table we see him shatter with another human beings body by throwing that body through that table from a height isn’t even the first table we’ve seen him fuck up in this basic way that evening, having ejected the Nipple to Nipple guy by wallopping him into a bunch of paying customers seated around one a few minutes earlier. (One of those customers was Foxworthy, so it’s hard to feel too bad about it, but still.) Not only is Morgan likely the most dangerous person in the bar to patrons of the bar, he’s also one of the most destructive to its property—and to their drink orders, at least one of which the guy above plummets through on his way to the ground. If Morgan’s job truly is to keep the peace in the Double Deuce, he really should start by bouncing himself.

That said, there is a pot/kettle element to Dalton’s callout of Morgan’s mien and methods. You’ll recall, of course, that Dalton’s first order of business upon officially assuming the position of cooler is firing Morgan during an all-hands meeting, as quoted above. But what is his first order of business upon officially assuming the position of cooler once the bar opens for business later that day? Breaking a table with a human face. Hypocrisy much?!?!?!

I doubt it. That’s not really Dalton’s style. As our examination of the Rules has made clear, apparent paradox and contradiction is virtually always a method of education via self-enlightenment. From this we can conclude that Dalton’s objection is not to breaking tables with human beings per se, but the mindset, method, and result of same. The Rules are instructive here, as they always are. “Never underestimate your opponent—expect the unexpected”? Look at Morgan’s face and tell me he’s not feeling the outrage of man who cannot believe what others have dared to do to him. “Take it outside—never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary”? Morgan is deeply inside his feelings; he has the object permanence of a furious toddler and fails to understand that no problem truly starts inside the bar, and thus can not properly assess the necessity of responding inside the bar in turn. “Be nice—until it’s time to not be nice”? I feel it’s safe to say that if you materially contributed to escalating a couple of punches thrown at Gawker by Sharing Husband into a rumble involving two dozen combatants capable of leveling the entire seating area, the time to not be nice had not yet arrived. Only the mind of a cooler knows the day and the hour. Morgan, you’re outta here.

080. Dodge

March 21, 2019

If there’s anything else in the history of action cinema I’ve studied with the same open-hearted intensity I’ve applied to Road House, it’s the Tomb of Balin/Bridge of Khazad-dûm sequence from Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring. Back in the summer of 2001, in the Before Times, I was invited by New Line Cinema in my capacity as assistant editor of the Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly, my first real job out of college (see what I mean about the Before Times?) to watch the 20 minutes or so of footage from Jackson’s first Lord of the Rings movie that had been publicly screened, initially some weeks prior at the Cannes Film Festival. Wisely the studio had selected the film’s first real action setpiece, the slobberknocker with the orcs and the cave troll in Balin’s Tomb and the flight down the crumbling staircase afterwards. Any doubts I might have harbored about the ability of Jackson, a filmmaker whom I loved for Heavenly Creatures but wasn’t sure could tamp down his manic style for Tolkien’s world, evaporated the moment the fighting began. This was a director who understood that effective action is shaped by the environment in which it’s staged, with easily understandable physical stakes for the success and failure of each blow and maneuver, relayed through camerawork that allows the eye to parse the spatial relationships between the combatants.

What’s more, and the friend I brought along with me as my plus-one to the screening room is the one who pointed this out, Jackson understood that the key to fantasy as a genre is scale, intuiting George R.R. Martin’s much-quoted dictum that we turn to fantasy “to find the colors again,” to transcend drab reality on (paraphrasing here) the wings of Icarus rather than Southwest Airlines. Neither Jackson nor Martin (nor Tolkien, nor Benioff & Weiss for that matter) felt this meant completely detaching the material from reality; on the contrary, the punishing realism of Martin’s setting and the painstaking detail of the Weta Workshop’s worldbuilding made the truly massive scope of the landmarks and lives of Westeros and Middle-earth all the more convincing.

I’ve told this story many times now, but it was specifically one of the Moria sequence’s action beats that brought this home to me. As the Fellowship flees down those gigantic, precarious stairs, orcs begin pelting them with arrows. Legolas, the Elven archer, turns and fires back at one of the distant foes. The camera travels as if mounted on the shaft, giving us an arrow’s eye view of the cave and the evil creature on the opposite end towards whom it is racing. A cut at the moment of impact switches us to a view of the same cavern from just behind and above the orc (by now struck right between the eyes and plummeting into the abyss below), angled downward toward the Fellowship on the stairs hundreds of yards away. The arrow’s flight, and our flight along with it, describes that vast space in a way a more traditional establishing shot could not. If we’d started with that over-the-shoulder shot looking down at the Fellowship we’d have gotten the picture I suppose, but we wouldn’t have been made to feel the space, the scale, the awe.

Whether to reserve the sight of the Balrog for the eventual filmgoing public or because that sight had not yet been completed I can’t recall, but the preview cut off with our final glimpse of the Fellowship escaping the stairs. The chase across the Bridge, the standoff between Gandalf and the Balrog, Gandalf’s triumph and fall, and the Fellowship’s mournful escape had to wait until the premiere. But there’s another moment with an arrow that stuck with me then and still does today. As Aragorn, the last one out of the Mines, looks back at the chasm, the rain of arrows from the orcs, who’d given the Balrog a wide berth, resumes. Viggo Mortensen, an amazing proficient action performer for a guy who had about a week of instruction before his first on-camera swordfight compared to the rest of the cast’s extensive training camp, had clearly been instructed by Jackson to act as though he was dodging arrows that were added digitally after the fact. Like a particularly generous pro wrestler he sold the hell out of it, at one point ducking so dramatically it’s like he was avoiding some big galoot’s haymaker. The desultory choreography of the move jumps out at me because Mortensen’s Aragorn is otherwise a model of physical efficiency in his fighting style, as befits a man who’s been hunted all his life and has learned that excess movement can mean the difference from ending a fight merely exhausted and ending a fight dead. It’s taken me time to come around to it but I now recognize it as the right approach for a character who’s been momentarily poleaxed by a grief he never believed he’d experience.

Anyway, at one point during the big bar-destroying fight that breaks out in Road House when a man squeezes another man’s wife’s tits without paying to kiss them as he’d appeared to agree to do, a stray bottle comes flying in Dalton’s direction and shatters against the post next to which he’s been standing and taking in the scene, and he dodges it and resumes watching in less time than it took either of the arrows described above to do their thing. This doesn’t tell us anything about the scale of the Double Deuce, the spatial relationship between Dalton and the unseen bottle-thrower, the nature of the world in which the film takes place, the emotional state of the characters, or the approach of director Rowdy Herrington toward the material. It just tells us that Dalton is so good at dodging broken glass that it doesn’t even disturb his spit-curl. And that’s all you need to know, son.

074. “Jesus Christ!”

March 15, 2019Jack is the voice of the people. Leave it to men like Dalton and Wade Garrett to take in the chaos of the bouncer lifestyle and reply with a wry smile and a quip, or with stoic silence. Less seasoned than his mentor and his mentor’s mentor before him, Jack has much of their inherent courage, decency, and adaptability, but lacks the sangfroid common to the cooler. When faced with, say, a bloodied Pat McGurn getting spin-kicked by Dalton through Frank Tilghman’s plate-glass office window, he’s not going to gently shake his head and chuckle to himself or something. He does what you and I might do: make a face conveying almost comical levels of disbelief and gasp “Jeeesus Chrrrist!”

It’s a not dissimilar reaction to the one he has when Horny Steve’s latest lady friends try to gain access to the Double Deuce by presenting, as ID, a Sears credit card. Sometimes we need a man like Jack to say “This is a Sears credit card” in such circumstances—not to elevate the problem to the realm of the philosophical as Dalton might, not to make light of it with a dick joke like Wade would, but just to call it like it is. Then he leaps over the bar and runs into the fray, because he’s still a character in Road House. But the point stands.

Indeed, when you see a guy get bodily launched through a window by an itinerant bar-knight, “Jesus Christ!” is not just appropriate but salutary. We in the audience are rarely afforded a reaction to the truly ridiculous violence in this film that acknowledges it as such; god knows that several times during my initial viewing, and often thereafter, I watched people get tossed into furniture or punched in the skull and thought the moral panic about violent action movies was eminently justified, even understated.

There’s a degree to which watching Road House is like getting punched in the nose and kicked into the next room. Jack gets it. He usually does. When he says “Jesus Christ!”, what he’s really saying is “I see you, Road House viewer. You are valid.”

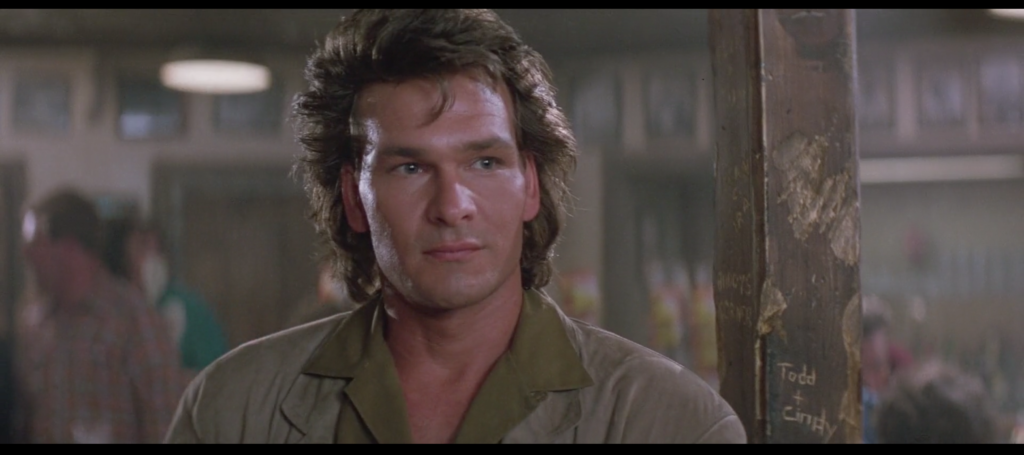

063. Patrick Swayze Beating the Shit out of John Doe from X

March 4, 2019Road House is a film in which Patrick Swayze beats the shit out of John Doe from X.

It’s simple, really. Sister-son Pat McGurn returns to his former place of employment with his uncle’s most useless enforcers O’Connor and Tinker in tow in order to force proprietor Frank Tilghman to reverse the decision of the bar’s new cooler Dalton and reinstate him to his position of bartender. Dalton takes very mild issue with the plan. Pat whine-gloats like a petulant child who thinks their parents are gonna punish their little brother and not them, then produces a knife the size of a machete and proceeds to simultaneously slash at and gay-panic taunt Dalton. Dalton punches his nose in. While he holds his hands to his broken face and howls in pain, Dalton spin-kicks him through a plate-glass window. He remains incapacitated for the duration of the fight that ensues, after which he is bodily carried out of the bar.

Concerned that Pat McGurn didn’t receive enough punishment? I’ve got you. First it’s important to note that by the end of the film Dalton will murder Pat McGurn, using the body of a dying goon to block Pat’s shotgun blast, then withdrawing the knife he’d inserted into the now dead goon’s gut and throwing it into Pat’s chest, causing him to misfire one last time and then plummet from a second-story landing to the ground below. Second you’ll notice from those screenshots that Pat’s nose was already bleeding before Dalton’s punch connected; you can call this slapdash continuity if you want, but I prefer to believe that either his body anticipated the damage that was about to be done to it and started hemorrhaging spontaneously, or that Dalton caused him to bleed without touching him by sheer force of chi. Or both! I’m not picky.

But here’s the bottom line, friends: Road House is a film in which Patrick Swayze beats the shit out of John Doe from X.

059. Men in Black

February 28, 2019When I wrote about Wade Garrett yesterday, I remembered something about his black t-shirt: He’s not the only cooler in the movie to wear one. The other of course is Dalton—but it’s not like he wears it all the time. The movie shows us he’s molded in Wade’s by deploying black in his wardrobe on three key occasions.

Attentive readers of Pain Don’t Hurt will have guessed the first by now: The Giving of the Rules. This takes place prior to Wade’s introduction, directly linking the older man’s debut to the establishment of his acolyte’s doctrine.

The second is the fight that takes place the night he and Doc have their first date, which is also the first time we see him on the job after we meet Wade. This reinforces the sense of succession while also tying Dalton’s romantic flourishing to the older man’s tutelage.

The third is his impromptu breakfast summit with Brad Wesley, during which Wesley brings up his checkered past and offers to hire him away from the Double Deuce. It’s not a t-shirt here but a collared shirt, as befits this more formal occasion. But the dialogue makes direct reference to an event in Dalton’s past that Wade will also bring up (while wearing a collared black shirt himself) later in the movie, and shows Dalton standing up to an asshole in a way that would do his mentor proud—even if he’d likely suggest getting out of Dodge afterwards.

Clothes make the man. Clothes mate the men.

048. The punchline

February 17, 2019For want of a nail the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe the horse was lost.

For want of a horse the rider was lost.

For want of a rider the message was lost.

For want of a message the battle was lost.

For want of a battle the kingdom was lost.

And all for the want of a horseshoe nail.

—traditional

“Hey buddy, what are you doin’? Are you gonna kiss ’em or not?”

“I can’t!”

“What do you mean, you can’t?”

“I ain’t got twenty bucks!”

—Road House

This concludes “The Agreement,” a seven-part special Valentine’s Week series. Thank you for reading.

041. Breaking a table with a human face

February 10, 2019If you want a picture of the Double Deuce, imagine a table broken by a human face — for ever. I’ve been thinking about the way Dalton grabs the Hawaiian Shirt Knife Nerd who was willing to defend his girlfriend’s right to dance on a table literally to the death by the back of his head and smashes his face down into a second table so hard and so fast that the wood splinters cleanly in half a lot lately. It’s a terrifically intuitive and forceful bit of fight choreography, that certainly helps. It conveys Dalton’s efficiency of movement and his power at short range, key to making him seem like a physical threat when half the characters in the movie say “I thought you’d be bigger” to him at one point or another.

Crisp editing by Frank J. Urioste and John F. Link (Die Hard, RoboCop, Predator, Commando, Total Recall, Basic Instinct, Tombstone) sells the move, but not alone. As an actor, Patrick Swayze takes a heretofore unprecedented turn for the savage in this moment, scowling with fury we’d previously seen no trace of at all. As time passes we’ll see more and more of this look from him. (To the extent Dalton has a character arc it’s largely one long descent that begins at a moment we’ll discuss in detail later in this series and ends with five murders.) Dalton traffics primarily in a blend of the Western and Eastern forms of coolness; he’s gunslinger tough and martial-artsist enlightened. The audience needs to see what happens when he gets heated up, and how little normal men can do to stop him when it happens.

When does it happen? This is important as well. The scene that precedes the table incident is none other than the Giving of the Rules, in which Dalton lays out his credo for successful bouncing and cooling. “Never underestimate your opponent/expect the unexpected”? Check. Dalton chose to act in such a way that this guy was done before he even realized the fight had started. No surprises coming from that corner. “Take it outside/Never start anything inside the bar unless it’s absolutely necessary”? Okay, sure, we’ll allow it. This bizarre little man drew a knife and threatened to murder a bouncer simply because he’d been asked to ask his girlfriend to stop climbing on the furniture. Sounds absolutely necessary to me. (And the Third Rule? Perhaps you know it already, perhaps you don’t. We will not be discussing it just yet. We will not discuss it…until it’s time to not not discuss it. Let’s just say that grabbing a human being by his hair and forcing his skull through a table sturdy enough to dance on speaks volumes on the Third Rule’s contents.)

What happens immediately afterwards? Everyone in the bar gazes and gasps in awe. People nearly move in slow motion, they’re so stunned by his prowess. Even the woman whose boyfriend has just been given some kind of concussion gingerly takes Dalton’s hand to be led down off the dancing table, and looks back over her shoulder at him on her way out of the bar. This is a man worth turning into a pillar of salt for. “The name…is Dalton,” Cody announces from the stage (through the chickenwire), after being filled in by his sighted bassist as to the nature of the hubbub—like a talk-show host announcing a guest, or the lead singer introducing the band. People in the Road House Universe absolutely adore people who break tables with other people’s faces.

Finally, there’s the savagery of the act itself. Powerful agent to the uninitiated. WA-BAM! He broke a table with a guy’s face! Didn’t even give him a chance! If you’re a first-timer and you reach this moment, any fears you may have had as to whether the first big barfight was the last time you’d see anything that gratuitously, moronically violent, this lays your fears to rest. You ain’t seen nothing yet.

038. The Laughing Man

February 7, 2019The men who look at Dalton are not the only Road House characters who model behavior for their audience. Nor are the women. To understand this movie, one must understand the Laughing Man.

An anomalously odd, almost Lynchian presence in a film that’s otherwise much more straight-down-the-middle in its abject stupidity, the Laughing Man is an avatar for the audience in that the events of the film transmogrify him from observer to participant.

A member of the rogues gallery that greets Dalton upon his arrival at the Double Deuce, he is at first content to simply watch the opening barfight unfold, giggling and guffawing and going slightly crosseyed like a cartoon woodpecker all the while. As a matter of fact, he is at second content to do so, and at third, and presumably ad infinitum. In an another world, perhaps one in which Wes Bradley successfully wooed the first Dillard’s to Casper, Wyoming, this hyena-man is still standing by the bar, laughing like a Joker henchman at everything that has since unfolded. The fool on the hill sees the goons going down.

But that is not the world we inhabit.

In this world, the ageless waitress who appears to have started working at the Double Deuce after quitting her job at Norma Jennings’s Double R lobs a bottle through the air, intending to hit some other asshole but clocking this harmless nimrod right between the eyes instead. He goes down with the kind of exaggerated overselling you see from pro-wrestling mid-carders, or from anthropomorphic animals around whose heads birds chirp in a saturnine orbit after someone hits them with a rolling pin.

The waitress looks upon her works and despairs. But should we? No! The Laughing Man is concussed so that we might continue. He shows us that no matter how much we might wish to laugh at this movie, it will draw us in until we have no choice but to laugh with it, or suffer for our refusal. You are in the Jasper of the mind now. Laugh and the world laughs with you!

037. Denise & Carrie Ann

February 6, 2019I was a theater kid in high school, and yes, I am glad you were sitting down. As the president of the Drama Club, the only coed activity my all-boys Catholic high school had to offer, I usually had better things to do than nitpick blocking, from learning my own steps to realizing how unforgiving for teenage boys pleated dress pants can be. But I did have one pet peeve I remember to this day.

Pretty much every musical in the high-school repertoire has around three or four major characters who—whether because they’re too old, too young, don’t sing, don’t dance, aren’t residents of the town/actors in the company/members of the Conrad Birdie fanclub, or any number of other factors—don’t take part in the big dance numbers, or aren’t active in the events of a particular show case scene. However, they are often at least present at those times, typically clustered in little groups around the perimeter. What would always bug me was when two characters who’d never spoken to each other before in the show, and for whom because of narrative economy it would be a big deal for them to speak to each other, like worthy of a song and dance of their own, wound up standing next to each other, stage-whispering about Professor Harold Hill’s latest chicanery or whatever.

I think about that when I watch Denise, Brad Wesley’s kept woman, and Carrie Ann, the Double Deuce’s coolest employee, team up during the first big fight. They cower together to shelter from the action. They root and heckle and holler as a unit. They wrap protective arms around one another when the going gets tough. Denise cheers Carrie Ann on when she starts slugging one of the participants. She actually hands her a bottle to use as a weapon!

Do these characters have anything in common? Do they have any mutual friends? Do they ever speak to each other…I was gonna say again, but really the phrase I’m looking for is at all? Do they even come within five feet of one another? If you’ve read thirty-six essays about Road House and counting you’re no doubt familiar enough with the film’s approach to continuity to answer those questions. But there’s a gigantic fight scene going on, and they’ve gotta stand somewhere, and the director is probably too busy telling gigantic men which tables to fall through, so a few perfunctory “stand over there”s are all they got, and they improvised. If it helps, imagine they’re the juniors playing Mayor Shinn and Mrs. Paroo, silently emoting together while forgetting to cheat toward the audience during “Shipoopi.”

025. Tableau

January 25, 2019Though Dalton gets stabbed within the first few minutes of Road House, it would be incorrect to refer to the incident as a fight. He weathers the cut with stoic grace, lures the wielder of the blade into the parking lot of the Bandstand under the false pretense of giving him the honor of a mano a mano throwdown, and then walks back inside, closing the gates of paradise behind him with a row of mountainous bouncers.

The real first fight occurs about 15 minutes in, when Dalton first arrives at the Double Deuce. Let us leave aside the manner in which the fight begins, for now; suffice it to say it involves the violation of a verbal contract and a subsequent falling-out between the negotiating parties. Let us also avoid discussion of the fight’s particulars, each of which will likely receive an entry of its own. Here our focus is on the fight’s gestalt. As much as the Shirtless Man or the Four Car Salesmen or the Bouncer Fame Index, it is an indication of the kind of movie you’re watching, and the most visceral and ambitious one at that. And it indicates this: You are watching a movie in which barfights achieve the colossal scale and cacophonous visual intensity of a painting from the Flemish Renaissance.

While, again, avoiding the instigating incident and the individual fight choreography beats, the effect of the first fight is intoxicating—a vertiginous ramping-up of wanton physical stupidity and destruction, from a starting point that is incredibly stupid itself, that simulates the effect of consuming an heroic amount of intoxicants in a time short enough to be the length of a song from Wire’s Pink Flag.

The first time I watched Road House I’d heard about it for a couple of years from the friends who wound up introducing me to it, but really had no idea what the fuss was about. By the time the first fight was over I wondered no longer. While I imagine there are those who do not give themselves over to the movie after this scene, I was not one of them, nor do I truly understand what it would take to be one of them. There’s no resisting the howitzer blast of shattered bottles, smashed tables, flying bodies, and punched heads you witness here, nor the rogues gallery of one-off stuntpersons who produce them.

And while Dalton himself stays out of the fray, watching it all unfold with the sangfroid only America’s second most famous bouncer could muster, you the viewer are afforded no such luxury. You pinball around with the camera as every act of stupendously dumb violence is rubbed right in your face. As a collection of individual moments, shots, characters, punches in the head, it’s truly impressive.

But when the camera pulls back and the full scale of the devastation is revealed for the first time? Breathtaking. Staggering. Clarifying. In that one moment you mentally whip-zoom from the trees to the forest, the way you might look back at a particularly harrowing stretch of events in your life and think “my god, how did I ever make it through?” The parts overwhelm moment to moment. The whole overwhelms on a whole other level, yet none of the parts are concealed. Everything is happening.

And you’ve emerged on the other side, with roughly a Tilghman’s eye view of the conflagration. You see the magnitude of the task Dalton has taken on, even as he casually strolls through the still-raging slobberknocker to confer with the bar’s owner. You see the movie you’re about to spend another hour and a half watching, itself a collection of individual moments, shots, characters, and punches in the head—just as chaotic as this one image, and just as cohesive a statement.