Posts Tagged ‘Comics Time’

Comics Time: Closed Caption Comics #9

May 25, 2011Closed Caption Comics #9

Pete Razon, Lane Milburn, Conor Stechschulte, Mr. Noel Freibert, Ryan Cecil Smith, Chris Day, Erin Womack, Andrew Neyer, Mollie Goldstrom, Molly O’Connell, Zach Hazard Vaupen, writers/artists

Closed Caption Comics, December 2010

192 pages

$20

Buy it and see preview pages from every contributor at Closed Caption Comics

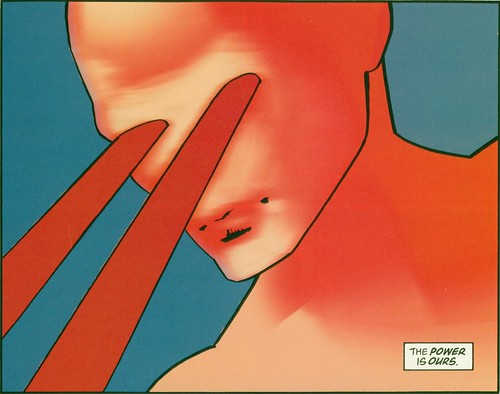

My favorite thing about the men and women of Closed Caption Comics is how much about their ways of drawing I just don’t get. I don’t get how Lane Milburn builds these beefy sci-fi-fantasy-horror creatures and warriors out of crosshatching and cleverly chosen angles and a line thick enough to look like it was drawn with a Crayola marker held in a fist. I don’t get how Conor Stechschulte creates his black images and blacker stories with lines piled upon wispy lines. I don’t get the thought process behind Mr. Freibert’s scraggly uniform-line-weight EC pastiches, with their abstract-lettering (???) interludes and endings that aren’t so much the usual O. Henry-by-way-of-the-Cryptkeeper twists but just the most ludicrously dark way the story could go. I don’t get Chris Day’s blend of chopped-up images, geometric shapes, block printing, and murky visual noise, and how it somehow fits so well with an elliptical tone poem about how The ’60s as a cultural force (from Marilyn to Manson) were a Satanic plot. I don’t get Andrew Neyer’s lightly penciled cross between a children’s storybook and a lo-fi Yuichi Yokoyama comic, its gutterless panel grids producing cross-image tangents that can be read as pure imagemaking in a way that belies his childlike character designs. I don’t get Molly O’Connell’s crazily ornate yet somehow messy figurework, her people who look like they were built out of tiny feathers. I don’t get how Zach Hazard Vaupen’s stuff doesn’t so much spot blacks as pour and smear them all over everything, reducing legibility but somehow increasing communicative power. Even the things I do think I can understand, like Ryan Cecil Smith’s cartoony parable, Mollie Goldstrom’s staggeringly detailed exploration of snowfall, Stechschulte’s painstakingly photorealistic drawings of a forest, Erin Womack’s elegantly iconographic tale of mystical violence, or Pete Razon’s knockout cover (which couldn’t speak more directly to me if it could literally talk), feel as though they emerged from a thoughtspace I could never quite access on my own, even if I recognize their results. That’s why I keep coming back to what they put out every time I see their table at a show, snapping up minicomics and eyeing their more expensive objects enviously. I don’t know where they’ll take me, but I know I’ll want to go there.

Comics Time: Gaylord Phoenix

May 23, 2011 Gaylord Phoenix

Gaylord Phoenix

Edie Fake, writer/artist

Secret Acres, 2010

256 pages

$17.95

Buy it from Secret Acres

Buy it from Amazon.com

Well now, here’s a pleasure: a book that gets steadily better as it goes on, so much so that by the time you finish it it’s as though you’re reading a second, later, better book by the same author. In some sense that’s literally true: Cartoonist Edie Fake serialized the story in the minicomic series of the same name over the course of years, so you’re seeing the work of an older, more experienced artist by book’s end. But his artistic growth isn’t just a “well hey, good for him” situation, it’s a happy complement to the growth of the wandering, questing title character. Watching Fake’s art tighten up — his placement of the characters on the page become more self-assured, his pacing become more controlled, his blank white pages fill up with elaborate psychedelic vistas and bold dot or grid textures and lovely two-tone color — does as much to show us his hero’s maturation as anything the character himself does or says or sees.

Like Kolbeinn Karlsson’s The Troll King, Gaylord Phoenix talks about homosexuality using the narrative language of myths and monsters with a pronounced art-comics accent. We first meet the Gaylord Phoenix (who’s a dome-headed, tube-nosed naked dude and not a phoenix at all) as he is about to be attacked by a crystalline monster; he survives the attack, but the wound he sustains carries within it an infection of aggression that eventually drives him to kill his lover. When the slain man is revived at the behest of a subterranean crocodile emperor, the phoenix returns to claim him, but the lover uses the magic now present inside him to cast the phoenix away. What follows is a journey consisting of encounters with various creatures and beings seeking to use the phoenix for their own ends, leading to sex, violence, enlightenment, and sometimes all three.

Fake is a lateral thinker when it comes to devising ways to depict all these things: The result, whether it’s a crocodile tail inserted through the anus and protruding out the mouth, penises that look like giant macaroni and thus can both penetrate and be penetrated, or a multiplicity of cocks that cover a crotch like the tentacles of a sea anemone, is racy, unexpected, a bit weird, and sometimes even a bit scary, which is pretty much how sex ought to be. But aggression is just as central to the story, a fact that’s unfortunate for the characters but a breath of fresh air in how it reclaims the province of traditional masculinity for homosexuality even while preserving queerness’ outsider identity. The climax (no pun intended) further emphasizes the importance of this synthesis, as the Gaylord Phoenix discovers that everyone he’s met on his journey is now literally a part of him, unleashed in what can only be described as the world’s first solo orgy. “It is all with me now,” he proclaims. “At last I hold my own…and partake of who I am.”

The problem with the book, I suppose, is right there: It’s a bit too neatly allegorical to ever truly soar, and its didactic conclusion left me feeling a little too much like I’d just heard the phrase “And the moral of the story is….” I wish the narrative had the crazy courage of the image-making — Fake’s beautiful block-print lettering, say, or the dark navy-blue-colored series of double splashes that conclude the book, or the way he can fill a page with tiny accumulated circles and waves that buffet and subsume, or the lovely tangerine halftone and clean rounded lines that comprise the phoenix’s final mystical encounter. But the key here all along has been to let the artistic growth on display speak for itself, to do the heavy lifting of the story itself. Actions speak louder than words.

Comics Time: Two Eyes of the Beautiful Part II

May 20, 2011Two Eyes of the Beautiful Part II

Ryan Cecil Smith, writer/artist

self-published, 2010

48 pages

$5

Buy it from Ryan Cecil Smith

Like the previous chapter, this installment in Closed Caption Comics member Ryan Cecil Smith’s adaptation of Kazuo Umezu’s horror manga Blood Baptism achieves something damn close to horror camp. It’s a celebration of the over-the-top nastiness and spectacle of horror manga: Not content to show the killer, a demented ex-actress out to repair her disfigurement by any means necessary, strangle a dog to death, Smith depicts the woman’s hapless daughter stumbling into a room full of dismembered animal corpses and getting buried in a pile of severed cat heads. Even the villain’s hair is larger than life, an enormous bun taller than Marge Simpson’s beehive. This is all the funnier for being drawn in an altcomix-meets-kids’-manga style; it could just as easily be an uglied-up Sailor Moon tribute comic some kid from CCS did. But it’s precisely this idiosyncracy — a member of one of the States’ premiere underground comics collectives doing a respectfully ridiculous cover version of a horror manga about a crazy woman preparing to rip her own daughter’s brain out to achieve eternal youth — that elevates it from cheap irony or schlock. From the expert zipatone shading to an immaculately inked centerfold spread of that room full of dead dogs (it’s all painstakingly delineated grains in the hardwood floor and shiny black puddles of blood), Smith is pouring a very serious amount of effort and craft into what could easily have been just a goof, because to him, it clearly isn’t. Most impressive to me is the way he depicts his little-girl protagonist’s reaction to her discovery of her mother’s true nature. As she panics and tries to escape, Smith crops her word balloons so they cut off the text of her speech so that only half the letters (top, bottom, left, right, whatever) are visible, the rest of each alphabetical character disappearing under the edge of the balloon or panel. Panel borders and balloon edges, the very containers from which comics are comprised, are inadequate to contain the overwhelming horror she feels. That’s a lot of smarts to bring to an arch horror-comedy experiment. It kicks the shit out of Black Swan, that’s for sure.

Comics Time: Lose #3

May 18, 2011 Lose #3

Lose #3

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

Koyama Press, May 2011

pages

$5

Buy it from Michael DeForge

It’s one thing to take a Chris Ware/Daniel Clowes middle-aged sad-sack comedy of discomfort and plop it into a slime-encrusted anthropomorphized-mutant-animal-inhabited post-apocalyptic hellscape that looks like Jon Vermilyea staging a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles revival in the middle of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. It’s quite another thing to do this well. And it’s still another thing to do it so well that while the whole is indeed more than the sum of its parts, the parts work all on their own, too. That’s the achievement of Lose #3, the latest installment in Michael DeForge’s old-school one-man alternative comic series.

In past issues, as well as in his minis and anthology contributions, DeForge has proven adept at crafting razor-sharp embodiments/lampoons of what have been termed “first world problems” and placing them in the mouths of fantastical, outlandishly designed and drawn creatures and monsters and superheroes and giant mecha and what have you. (“I feel like things have been weird between us lately,” reads the image of the shaggy faceless beast rolling around on the ground — that sort of thing.) And he does that here, too, to cringingly devastating effect: The text for the opening one-pager is a letter from a fresh-faced intern high on his first trip to NYC to his mother back home (“I asked if there were any paid positions opening at the magazine in the fall. They said things were still up in the air for now. Fingers crossed, I suppose!”), juxtaposed against the images of a naked man riding a spotted deer through a debris-strewn wasteland in order to pour the coffee he purchases at a still-standing chain coffee house into the maw of the creature that lives in his cave. Toward the end of the collection, ants wax pessimistic about life in these weird, dark times (“But, like — why do we live this way? It’s — it’s nuts that this is the ‘norm’ for us,” says an ant about the potential for human beings to burn them with magnifying glasses) and debate whether or not to move the dead body of a friend when its pheromones start attracting a crowd (“Just leave it. It’s a party”) Even in the main story, there’s a bit where the two teenage sons of our divorced protagonist talk about The Wire that nails the clichés of that particular conversation so accurately even without mentioning it by name (“The show introduces a new part of the city at the beginning of each season, so it’s always, like, BOOM! Bigger picture! BOOM! Bigger picture! You know?”) that I wanted to delete my old blog entries about the show.

The innovation of “Dog 2070,” Lose #3’s centerpiece story, is, well, that it’s a story, a look at a very shitty month in the life of a middle-aged flying-dog-man-thing. He concern-trolls his ex-wife over her current husband, his attempts to connect with his teenage and twentysomething kids are rebuffed with casual cruelty, he fixates on his own problems to the pint where he can’t empathize with cancer patients, his neurosis leaves him equally unable to spend his time at the computer productively writing or unproductively masturbating, he drunkenly confronts his middle-school son’s ex-girlfriend after a cyberbullying website the kid made about her nearly gets him expelled from school, he ends up in the hospital after a freak gliding accident. It’s easy to focus on the yuks here, which are abundant in the same way they are in Wilson or Lint — the sudden reveal of our hero Stephen’s inebriation when talking to his kid’s ex is impeccably timed to elicit an “Oh, Jesus” guffaw, and DeForge nearly always chooses dead-on details to illustrate the guy’s creepy self-absorption, from giving his ex-in-laws gifts on Thanksgiving just to stay in their lives to interrupting a conversation about a co-workers chemo to announce he’s begun therapy as research for his screenplay. (The flying scene, in which a soaring Stephen sums it all up by saying “Sometimes it’s as if I forget we’re able to glide!,” then crashes into a bird, is a bit on the nose, though.) But DeForge reveals the true emotional stakes in a pair of dream sequences as recounted by Stephen to his therapist. In the first, we watch the flesh slowly slough off his daughter, who recently attempted suicide, before she fades away from view; in the second, he and his former family, reduced to four-legged animalistic versions of their anthropomorphized selves, fight over a scrap of meat. “I just feel so ashamed I don’t know why. I’m watching it and I just feel awful.” This, of all the notes he hits, is the one he chooses to leave us with, a nightmare representation of a failing man’s worst fears and shames, to which he has no adequate response and to which no adequate response is provided. That’s when you realize that these emotional stakes have been present all along, hiding in plain sight: In the omnipresent beads of sweat oozing down Stephen’s fleshy body, in the debris-strewn streets and burned-out buildings that form a backdrop for the story, in the walls that seem to sweat and drip and bleed themselves. Something is wrong, the art says, even as the narrative chronicles the banal travails of a relatively normal guy. DeForge doesn’t need to come right out and say it himself. Lose #3 isn’t the bolt-from-the-blue paradigm-shifter I’ve seen some people describe it as, but it’s a confident enough comic that it doesn’t need to be, pushing its author out of his comfort zone only to discover he’s perfectly comfortable here, too.

Comics Time: Garden

May 16, 2011 Garden

Garden

Yuichi Yokoyama, writer/artist

PictureBox, May 2011

320 pages

$24.95

Buy it from PictureBox

Buy it from Amazon.com

Meet the non-narrative pageturner. Garden is Yuichi Yokoyama’s third English-language release from PictureBox, and his most viscerally thrilling work to date. It’s the clearest demonstration yet of the innovation that is his masterstroke: fusing visually and thematically abstract material with the breakneck forward momentum, eye-popping spectacle, and pulse-pounding sense of stakes of the rawest plot-driven action storytelling.

Garden has no story to tell, of course, not as such: It simply depicts a large group of sightseers who break into a vast manmade “garden” of enormous natural features combined with artificial and mechanical objects, wander around, and describe and inquire after what they see. With their matter-of-fact pronouncements (“There are many ponds. This one is jagged. There is a giant ball floating in this one. This one is made of stainless steel. We have now arrived at a significantly larger pond.”) doing the heavy lifting of parsing exactly what we’re looking at for us, we’re freed to simply go along for the ride, marveling at each new environment Yokoyama dreams up. As a feat of sheer bizarre imagination it’s tough to top: I can easily picture standing around with other readers comparing favorites — “I liked the hall of bubbles!” “I liked the stack of boats!” “I liked the river of balls!” “I liked the giant book!” “I liked the polaroid carpet-bombing!” “I liked the monkey bars!” Imagine if everything in Walt Disney World were as alien and strange as the giant golfball Spaceship Earth and you’re almost there. Nearly every new area and attraction practically demands to be stolen and used for a setpiece in someone’s weird alt-SFF webcomic. And with a “narrative” through-line that’s 100% pure exploration — lots of little guys walking and climbing and sliding and crawling through doorways and scaling mountains made of glass and so on — echoes of their tactile, discovery-driven adventure can’t help but hit us and excite us as we race along with them to their eventual destination.

In essence, Garden teaches you how to read it. It immerses you in its perambulations and presents you with a new amazing thing with each turn of the page, engrossing you to the point where you hardly even notice that it’s a book-length exploration on Yokoyama’s part of geometric shapes, of the clean line, of costume design (all the little people wear headgear and outfits that make them look like a cross between Jason Voorhees and Carmen Miranda), of his own fascination with the way the natural world and the manmade world shape one another. I felt at the end of the book like I do at the end of a great theme-park vacation: Exhausted, invigorated, and already planning my return.

Comics Time: Paying For It

April 5, 2011Paying For It

Chester Brown, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, April 2011

292 pages, hardcover

$24.95

Buy it from D&Q

Buy it from Amazon.com

My publishers wanted this book to be called PAYING FOR IT. I don’t like the title — there’s an implied double-meaning. It suggests that not only am I paying for sex but I’m also paying for being a john in some non-monetary way. Many would think that there’s an emotional cost — that johns are sad and lonely. There’s a potential health cost if one contracts a sexually transmitted disease. There’s a legal cost if one is arrested. If one is “outed,” then one could lose one’s job and also suffer the social cost of losing one’s friends and family. I haven’t been “paying for it” in any of those ways. I’m very far from being sad or lonely, I haven’t caught an S-T-D, I haven’t been arrested, I haven’t lost my c areer, and my friends and family haven’t rejected me (although I should admit that I still haven’t told my step-mom.

So far, I’ve been paying in only the one sense. (Since this is a memoir, “so far” is all that’s relevant.)

But let me be clear that my publishers did not force the title on me. I chose to give in to what they wanted. If I had insisted, they would have allowed me to put whatever words I wanted on the cover. I love and respect Chris and Peggy and realize that this is a difficult book to market.

–Chester Brown, in the entry pertaining to the Cover in the “Notes” section of Paying For It

“Difficult book to market”? Get outta town, Chet! When a review copy arrived at my house unexpectedly this Saturday, I tweeted, and quite seriously meant it when I did so, that having an infant in the neonatal intensive care unit was literally the only thing stopping me from dropping everything and reading this book right then and there. A parametric memoir from Chester Brown, the parameters of which were one of the great North American cartoonist’s experiences with prostitution? Appointment reading! Maybe it’s tough to market to the great unwashed, but you’d have to pry this thing out of my hands to keep me away.

As it turns out, Brown is right about the title his publishers selected. With its punning double meaning and slightly censorious elision of what, exactly, is being paid for, it’s all wrong for this straightfaced, blunt, even didactic sexual autobiography/soapbox lecture. “Paying for Sex” would be far more appropriate. Drop the cap from the “For” to make the phrase less idiomatic, insert the actual act back into the proceedings, and be as matter-of-fact and up-front as possible about what’s going on — which quality, not at all coincidentally, is a big part of why prostitution appeals so much to Brown in the first place. The social cues he seems unable to pick up on, the rituals he is congenitally incapable of performing, the years and decades of accrued guilt and sense of failure he built up from missing out on potential romantic or sexual relationships, the elaborate and to-him draining emotional quid pro quo of sex within the context of the few relationships he was able to enter into and maintain (that’s the context in which he really “paid for it”)…all of that disappeared the moment he told his first whore “Uh, I’d…like to have vaginal intercourse with you.” (“Yes, that’s what I really said,” he assures us helpfully in the “Notes” section.) It seems a shame to add a level of kabuki to the title of a book so fixated on taking it away.

This is not to say that humor has no place in the book. On the contrary, this thing is fucking hilarious. Much of this stems directly from how Brown draws what he draws. His Harold Gray tribute from Louis Riel has been abandoned (with the exception of Brown’s brother Gordon, who’s drawn like a Riel refugee). In its place are rigorous, unyielding two-column eight-panel grids filled with tiny, tiny people drawn in as smooth a line as you’re likely to see anywhere; “painstaking” is the word that comes to mind. Foremost among these tiny people is Brown himself; his self-caricature is gaunt to the point of skeletal, an impression enhanced by the pupil-hiding blank voids of his everpresent eyeglasses. (One of the “Notes” reveals that by a certain point in the narrative he’d begun wearing contact lenses, particularly when patronizing prostitutes, but he didn’t want to confuse the issue.) Seeing his eyeless face in three-quarter profile over and over and over and over and over again, page after page after page, is bizarrely hysterical after a while. It is the least sexy self-portrait possible — not just unsexy, but almost devoid of the energy one would think would be required to have sex at all. In the many scenes where Brown is accompanied by his best friends and fellow cartoonists Seth and Joe Matt, the portraiture gets funnier still. Watching the three bespectacled men — Brown balding and sullen, Matt babyfaced and effusive, Seth impossibly dapper and never without his suit, fedora, and cigarette — walk in lockstep down the city streets like some sort of morose urban Three Amigos is one of the unexpected comedic highlights of my comic-book year so far.

I know, I know: What about the fucking? Pretty funny too. Throughout the book Brown uses a sort of dilation effect to center one’s attention in each panel, tending to shade in the periphery of the panels with a circle of black, like an old silent movie. This is barely even noticeable until you hit the sex scenes, which tend to show a bareassed Brown silently thrusting away at the crotches of the whores in question, usually with several different physical configurations per encounter (which is to say per chapter, since each experience with a prostitute gets its own chapter). Before long Brown’s mid-coitus interior monologue features him calmly assessing the pros and cons of each prostitute — he thinks about how she stacks up against previous women he’s been with, whether or not to patronize them again, what kind of review he’ll give them on a website for clients of Toronto escorts, and so on. It’s so deadpan he might as well be in the produce aisle squeezing melons.

Which is the point. In the lengthy, handwritten prose section that ends the book — first a series of polemical Appendices detailing Brown’s exact position on the decriminalization (not legalization! keep the government out of it!) of prostitution and his responses to arguments against the profession, then a response from Seth to his depiction as a character in the book (“The truth is, Chester seems to have a very limited emotional range compared to most people. There does seem to be something wrong with him.”), then another series of Notes on various points of interest in the book — Brown advances an admittedly quixotic vision of a world where paying for sex is an utter commonplace, a practice so pervasive that the need for professional prostitutes is lessened because you or I would have no problem exchanging money for sex with our attractive friends and acquaintances and vice versa, the same way we might go to movies together or send a friendly email. The important thing to Brown isn’t just decriminalizing the supposed offense of giving or receiving money for sex, it’s deflating the romanticized aura of the act itself.

As you’ll learn at great length from Brown, both in monlogues within the comic and in the prose material appended to it, the book isn’t so much about prostitution in and of itself as it is about the way Brown has rejiggered his life in order to avoid the “evil” of romantic love, or “possessive monogamy” as he comes to exclusively put it. Unlike familial or friendship love, romantic love in its idealized form is exclusive — you love one person, that one person loves you, and neither of you is allowed to feel the feelings you have for one another or have the sex you have with one another with anyone else. This leads to jealousy, an emotion Brown views as immature and immensely destructive. The solution? Separate sex from its romantic context entirely. Have close friends and companions from whom you get all the benefits of friendship love, which is superior to romantic love anyway, and then have sex with people of whom your contractual obligation to whom ensures that you will have no further expectations, nor they of you. Sex is sacred, Brown argues — so it should be made available without stigma or shame to as many people as possible. What better way to accomplish this than cash?

So that’s the platform here. Brown wants to do away with romantic love, and prostitution has enabled him to do this.

Except for one jaw-dropping revelation he sneaks into the final eight pages’ worth of comics: UPDATE: Actual revelation redacted, but suffice it to say it calls into question, if not outright undermines, all the Big Ideas he’s been advancing all along. This is the key to the whole fucking thing, and he shoves it away in a single chapter! If this is the way life is to be lived in Brown World, then don’t we need to see how it’s lived if the entire project is to have any value? That’s where the rubber hits the road! So to speak!

And once you realize that Brown has pulled the knockout punch, so many other things you’d been willing to overlook due to his overall breathtaking candor and craft become harder to excuse. Every prostitute we meet, for example, is depicted as a faceless brunette. Now, it’s abundantly clear why he wouldn’t want to actually draw these women true to life even without his notes explaining this decision, but noting that he did in fact see prostitutes who weren’t pale brunettes doesn’t change the fact that that’s how he drew all of them — nor does it make the fact that he drew their naked bodies as accurately as possible but left them a faceless raven-haired horde otherwise any less unwittingly (?) revealing.

Then there’s the chapter where he has sex with a very young-looking, foreign-born prostitute who gasps in pain throughout intercourse: “That she seems to be in pain is kind of a turn-on for me, but I also feel bad for her. I’m gonna cut this short and cum quickly.” What a gentleman! In the Notes he reveals he was astonishingly naive — credulity-stretchingly so, to be honest, for someone who appears to be so well-educated in every other aspect of the literature of prostitution — about the existence of sex slaves, whom he continuously talks about as though kidnapping by force were the preferred method of harvesting them, as opposed to false-pretense illegal-immigrant indentured-servitude. “Was ‘Arlene’ a sex slave? She didn’t seem like one,” he shrugs in the Notes about this painful encounter, before quoting someone on how “outcall” prostitutes (those who come to your apartment) are unlikely to be sex slaves since they could always go for help instead. Anyone who’s watched a single episode of Law & Order: SVU or Dateline NBC could shoot this whole element of things so full of holes you could use it as a colander.

The thing is, like Brown, I don’t think the existence of sex slaves necessitates the continued illegality of prostitution, any more than the existence of labor slaves meant we should ban the harvesting of cotton or the performance of housework. He’s quite right to say that were prostitution decriminalized, law enforcement could focus on forced prostitution that much more readily. It’s the “forced” that matters, not the “prostitution.” But for a guy who’s so willing to extrapolate universal principles from his personal experiences — his mother’s disastrous, effectively lethal course of treatment for schizophrenia means schizophrenia doesn’t exist; his unhappy experiences with romantic relationships mean that romantic relationships are a categorical evil — he sure doesn’t mind leaping right the fuck past any personal experience, or those of anyone else, that might cause those principles harm. And, you know, hey, that’s how almost all of us live, to one extent or another (most of us not to the extent that we need to wonder whether or not a given sex partner is a sex slave, but to some extent at least). That’s human, and we forgive each other for it in life. In art? Art explicitly dedicated to the advancement of some philosophical and political truth? Then that’s the sort of thing you gotta pay for.

Comics Time: The Cardboard Valise

March 7, 2011The Cardboard Valise

Ben Katchor, writer/artist

Pantheon, March 2011

128 pages, hardcover

$25.95

Buy it for damn near 50% off right now at Amazon.com

Comics Time: Angel

February 23, 2011Angel

L. Nichols, writer/artist

self-published on the web, September 2009-August 2010

129 pages

Read it at DirtBetweenMyToes.com

I worry that I over rely on comparing comics to still other comics when reviewing them, but once this comparison occurred to me there was no way I wasn’t gonna use it: L. Nichols’ Angel is like Benjamin Marra’s Night Business crossed with Megan Kelso’s Artichoke Tales. Like the former, it’s a straight-faced homage to the trash aesthetic of late-’70s/early-’80s black-and-white genre comics and grindhouse/straight-to-video movies — this time it’s not erotic urban slasher thrillers being saluted, but post-apocalyptic gang-warfare stories. And like the latter, it’s using a somewhat disreputable genre as a filter for a story about violent conflict’s disruptive effects on friendships, love, and sex — Angel‘s funneling of queer sexuality through an idiosyncratically Brooklynite (lots of bike-riders!) Warriors-scape replaces Kelso’s multi-generational saga of lovers tossed around an epic anthropomorphized-artichoke fantasy framework by the winds of war

To be sure, it’s not quite as accomplished as either of those works. In a way, the seriousness of the emotional stuff Nichols is working with undercuts one of the great strengths of Marra’s comparable comics, which is how hard he can make you laugh at the sheer go-for-the-gusto-ness of it all. Where Marra’s sex and violence is garish, gaudy, and over-the-top, Nichols’s is a bit subdued and somber, and ironically that makes the pulpy prose (see page one above) harder to swallow. At the same time, though, the romantic entanglements, however far afield they roam in terms of the gender and sexuality of the participants, are much more firmly in the straightforwardly star-crossed lovers mold of traditional genre comics and movies than Kelso’s richly imagined couples and families. Moreover, the action sequences tend to be pretty much one beat per panel, making it difficult to get a sense of where characters are in relation to one another or what the consequences of any given shot or swing or explosion really are. The climactic battle sequence builds up an impressive momentum with its page after page of isolated action incidents, but in smaller doses, this method of pacing can be frustrating.

But that pacing is hers. That’s the important thing here, I think. And that melancholy combination of over-the-top ’80s-action cheese and bodice-ripping (or strap-on-wielding) romantic intensity is hers. Like the best alt-genre/”new action”/fusion comics, Angel isn’t an artist molding her ideas into a preexisting template, it’s her using her ideas as the template, and pouring bits and pieces of the genre art she loves into the mix to fill it up. When it works, it’s really exciting: Those staccato panels, which hardly ever show two people in the same frame and frequently don’t even show entire faces, create a real sense of paranoia and insecurity in that post-apocalyptic landscape. And the romantic material is affectingly personal despite its clichés. It’s not an action comic with heart, it’s a heart comic with an action, if that makes any sense. It’s not intended to be rad or stylish or awesome or sexy or cool or now, it’s intended to be exactly the combination of personal preoccupations and obsessions that it is. If I could say that about all alt-genre comics, whatever their other flaws, I could read them all damn day and still feel like I wasn’t cheating myself of the unfettered personal expression the best of the “alt” side of that equation can offer.

Comics Time: “His Face All Red”

February 21, 2011“His Face All Red”

Emily Carroll, writer/artist

self-published on the web, October 2010

Read it at EmCarroll.com

I’ve said a lot of complimentary things about this comic in the months since it was first posted, but it occurred to me I never actually sat down and reviewed it. So the other night I loaded it up for re-reading with the express purpose of writing a review in mind. And despite having looked at it however many times since it went up on Halloween, I still found myself dreading, literally dreading, the final image. Familiarity bred fear. From the striking title to the matter-of-fact opening line to the final page turn, Emily Carroll’s “His Face All Red” is an engrossing, quietly terrifying horror comic. You could be forgiven for thinking it might not be, by the way. Carroll’s slick-sexy-cute illustration style is very popular on the Internet, the kind of stuff that gets endlessly reblogged and Tumblrd and LJd; it’s easy to picture her earning plaudits for doing realistically cute redesigns of Supergirl’s costume, or a killer suite of Scott Pilgrim or Harry Potter portraits, or a drawing of Mal Reynolds and The Tenth Doctor reenacting Alfred Eisenstaedt’s “V-J Day in Times Square,” or whatever. So yeah, I could stand to see it de-prettified in the future. But here she applies that readily appealing craft in ways above and beyond what she could have easily gotten away with doing. Her use of the web to control pacing is really masterful: She uses the long vertical scroll to create an almost hypnotic feeling of inevitable descent as we watch our narrator explain why and how he killed his brother, and try to figure out why and how someone who looks and acts just like him appeared the next day, acting like nothing had happened; she then breaks this flow in jarring fashion with a pair of pages that contain but a single indelible image, one after the other. All this against a pitch-black background, further enhancing the immersiveness of the story. And that final turn of the page! Really pitch-perfect cartooning and pitch-perfect horror pacing, showing us just enough to let us know that something truly terrible is before us. I don’t want to spoil anything, but I found that in the weeks since I last saw it, my mind had added details to the image — they weren’t really present there, but the tone of utter shattering of reality’s norms conjured them nonetheless. Enormously effective and affecting work, as close to delivering a jump-scare as any comic I’ve read. Shudder.

Comics Time: “2001”

February 18, 2011“2001”

Blaise Larmee, writer/artist

self-published on the web, January 2011-

Read it at BlaiseLarmee.com

What a thrilling comic. It’s worth noting, I suppose, that the white-on-black presentation of Blaise Larmee’s gorgeous webcomic “2001” largely removes Larmee’s work from the pencil-smudged, fragile-lines-on-white, Darger/CF context in which it’s previously been located. But far more interesting to me than how the comic operates versus Larmee’s other stuff is how it operates in and of itself. The vastness of the full-bleed images, the fact that they occupy the entire page, the way the starfield/snowfall background is a big black nothing that appears to isolate the characters in infinity, is immediately impactful, even awe-inspiring, maybe the most striking use of the webcomic medium I’ve ever seen. Now that enough pages have accrued, however, we discover that Larmee isn’t just tracking bodies in space, but bodies in a particular space. The big geometric planes of white and black that interrupt the snow/stars, we can now tell, are a building or structure of some sort — the white its roof, the black its walls — around which our two heroines twirl and leap and walk and peek. Storywise, there’s not much more to it at the moment, beyond some almost Bendisesque cute dialogue about how “very May ’68” the place is and how they’ve got tea but want coffee instead. But there needn’t be more to it than what there is: An innovative, arresting, and beautiful way to arrange movement on a comics page, and to arrange a comics page, period.

Comics Time: “Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010”

February 16, 2011“Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010”

Matt Seneca, writer/artist

self-published on the web, February 2011

52 pages

Read it at Death to the Universe

Talkin’ ’bout his g-g-g-g-generation. When he’s not making comics, Matt Seneca is best known as a promising new critic of the things, one of the very few who have emerged on the internet over the past few years who engage with alternative and art comics with any regularity. He does this in post-post-post fashion. For starters, he’s part of the first wave of post-Comics Comics critics. Dan Nadel, Tim Hodler, and Frank Santoro could take the work done by Gary Groth and The Comics Journal in carving out a critical space for comics of genuine literary ambition and execution as read, enabling them to eschew the Journal‘s then-necessary ruthless aesthetic elitism and reclaim genre comics as a valid and fecund field for criticism. (At its best, the young comics blogosphere — and its print funnel, Dirk Deppey’s Comics Journal — did some of this work too, especially the inestimable Joe McCulloch, but I think the Nadel braintrust, through its multiple venues (CC, PictureBox, The Ganzfeld, Art Out of Time), really put it over the top.) In turn, Seneca exists in a world where the Journal‘s distinctions are a pretty distant memory, a world where in the wake of the CC crew’s rehabilitation project, genre work of whatever sort can be unhesitatingly and unashamedly examined with all the close-reading intensity and epiphanic emotion anyone ever brought to “The Death of Speedy Ortiz.” Seneca is also probably several years deep into the post-Internet cohort, a group that never saw print as the primary outlet for criticism or goal of its writers, a group that didn’t exist even five years ago. As such, personal critical interests, obsessions, and conundrums can be pursued with a length and an idiosyncratic focus unthinkable to any primarily-print writer (Kent Worcester excepted). Finally, he’s post-Tucker Stone/Mindless Ones/Noah Berlatsky, the performance-art superstars of Internet comics criticism. Though each of these writers (or group of writers in the Mindless Ones’ case) is very different, each embraces a style of writing and an approach to criticism that (for better or worse — which one really isn’t important here, however) makes them the star of the criticism as much as the work in question; I know this is old news in, say, rock crit, but in my experience growing up, comics critics, even the most outspoken ones, basically wanted to get out of the way of what they had to say about the comics they were talking about. The Mindless Ones’ Morrison-under-a-microscope rhapsodies, Stone’s insult-comic/battle-rap smackdowns, and Berlatsky’s indefatigable, Google Alert-enabled contrarianism all require readers to engage not just their analysis of and opinions on the work, but the way that analysis and those opinions are performed.

Not that anyone ever asked, but I’ve got some problems with all of this. I find that the focus on artsy genre stuff, or genre stuff that can be reinterpreted as artsy (Carmine Infantino?), can get monotonous (must every comic deliver thrills and sexy cool explosions?) and myopic (won’t somebody think of John Porcellino?) and lead to the lionization of some pretty middling work (like Brendan McCarthy’s dopey, weirdly racist Spider-Man: Fever). And I think the tendency to wax loquacious, coupled with the use of a given comic to put on a little show about lots of other things besides, can lead to some errors in interpretation and judgment because the error feels more right than what might result from a more rigorous interrogation of the work. Not every comic, and certainly not every cartoonist’s entire career, can be sussed out from a single panel in “as below, so above” fashion, and all the passion in the world can’t make The ACME Novelty Library #20 a work of life-affirming optimism or people’s discomfort with Ebony White in The Spirit comparable to idiots’ discomfort with the use of “nigger” in Huckleberry Finn.

So there’s that. Or maybe I just like shorter, more direct criticism. Maybe I just like reading about contemporary works that don’t feature extraordinary individuals solving problems through violence. Or maybe I would like to have been half the writer Seneca is at his age (my shit was pretty embarrassing) and had (or have! who knows?) half the audience he does, or would like to be able to convincingly make comics myself instead of just writing them and/or writing about them.

Point is, I brought a lot of baggage to “Flash Roughs/In a Hole: Jul-Aug 2010,” Seneca’s breakout work as a comics creator. In comics form, it synthesizes many of the features and factors Seneca brings to the table as a critic into art of its own. In fact, the comic itself is both comic and comics criticism: Interwoven with intensely confessional writing about Seneca’s break-up with his fiancée is astute, self-reflexive, process-based discussion of Seneca’s attempt to create a (bootleg, highly personal) comic starring the Flash, as well as passages about the sensual qualities of the work of Carmine Infantino and Guido Crepax delivered in more-or-less straight (albeit handwritten) prose. It feels like the logical place for Seneca’s criticism to go. Both style and emotional impact are such a big part of his critical writing; what better way to enhance both than making that critical writing into actual art that pleases the eye with its bright reds and yellows and bold hand lettering, that aims straight for the heart and gut with ripped-from-real-life doomed romance? Seneca knows his limits as a draftsman — that’s part of what the comic is about, his earlier self coming to terms with how his Flash comic was likely to look when he “finished” it and realizing that the “rough,” pencil-only version might make for more powerful comics — and compensates for it with eye-grabbing color and a welcome willingness to let words work as pictures. Much of this is done literally atop notes in Seneca’s sketch/notebooks — notes for the Flash comic, notes from the art class he was taking at a time; these bleed through and are pasted over in Brian Chippendale Ninja style. You’ll never feel bored reading this comic, never feel like your eyes or mind are being underfed, and this is one of the great strengths that artcomics, which need not meet any of the obligations of the representational, can bring to the table. Seneca, a voracious reader of comics, knows what he can do with the things.

And the same self-awareness he brings to craft concerns forms the lynchpin of the narrative: Knowing full well that we probably got there pages and pages ago, Seneca self-effacingly walks us through the achingly long time it took him to realize that the super-sexy, super-smart new character he’d introduced for his Flash comic wasn’t just a tribute to Crepax’s Valentina, but quite obviously and painfully to his increasingly estranged girlfriend as well. Once they break up, the comic is lost to him forever. Anyone who’s tried their hand at making art will recognize that feeling, that you’re often the last person to figure out what the art you’re making is about.

Even still, I’ve got my reservations about the comic — not so much what it’s about, but how it goes about it. Any work this profoundly personal and traumatic for the author makes those who find themselves unable to get fully on board feel like churlish heels, but c’est la vie: I think I’m past the point where I can appreciate doomed glamour. I don’t see anything glamourous about doom anymore. So when Seneca scrawls “WHEN LOVE LEFT MY LIFE” in giant block letters that take up nearly an entire page, or writes “SHE LEFT.” in white against a black block background, or fairly casually drops in some drug references, or ends on a lightly scrawled note of uplift centered against a blank spread, these things feel calculated for maximum Tumblarity to me, like a fashion photo of a pretty girl in a Joy Division t-shirt. (I am not immune to such things’ charms, to be sure! But that’s on me.) And the writing gets mighty purple in the big climactic (heh) pre-breakup “tonight’s the night, it’s gonna be alright” sex scene. Again, I’m not about to deny that this is how this felt to him in that moment, but sometimes in art as well as in criticism, you need to remove yourself from the equation. Of course, you could just as easily say that maybe I need to take my own advice.

Comics Time: The Dark Knight Strikes Again

February 14, 2011The Dark Knight Strikes Again

Frank Miller, writer/artist

Lynn Varley, colorist

DC, 2003

256 pages

$19.99

Buy it from Amazon.com

Originally posted on October 28, 2009 at The Savage Critic(s).

Years ago I came across an eye-opening quote from Jaron Lanier in the liner notes of the reissued Gary Numan album The Pleasure Principle. Google reveals that it was pulled from this Wired essay. Here’s what it said:

“Style used to be, in part, a record of the technological limitations of the media of each period. The sound of The Beatles was the sound of what you could do if you pushed a ’60s-era recording studio absolutely as far as it could go. Artists long for limitations; excessive freedom casts us into a vacuum. We are vulnerable to becoming jittery and aimless, like children with nothing to do. That is why narrow simulations of ‘vintage’ music synthesizers are hotter right now than more flexible and powerful machines. Digital artists also face constraints in their tools, of course, but often these constraints are so distant, scattered, and rapidly changing that they can’t be pushed against in a sustained way.”

Lanier wrote that in 1997. I’m actually not sure which vintage-synth resurgence he was talking about, unless you count the Rentals or something (although everyone and their grandfather was namechecking Gary Numan back then, which was sort of the point of including the quote in the liner notes. Maybe he meant Boards of Canada?).

But golly, it sure seems prescient now, huh? Here we are, in the post-electroclash, post-Neptunes, post-DFA era. The hot indie-rock microgenre is glo-fi, which sounds like playing a cassette of your favorite shiny happy pop song when you were three years old after it’s sat in the sun-cooked tape deck of your mom’s Buick for about 20 years. And my single favorite musical moment of last year, as harrowing as those songs are soothing, was the part of the universally acclaimed Portishead comeback album that sounded exactly like something from a John Carpenter film score. (It’s at the 3:51 mark. It’s awesome, isn’t it?)

And that’s just on the music end. Visually? Take a look at Heavy Light, a show at the Deitch Gallery this summer featuring a murderers’ row of video artist specializing in primary-color overload and technique that doesn’t just accentuate but revels in its own limitations. Foremost among them, at least for us comics folks, is Ben Jones, member of the hugely influential underground collective Paper Rad and recent reinterpreter of the massively mainstream The Simpsons and Where the Wild Things Are. But the ones with the widest cultural import at the moment are Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim of the astonishingly funny and bizarre Adult Swim series Tim & Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!. Their color palette is garish, their digital manipulations are knowingly crude, and their analog experiments are even more so. When they combine the three, god help us all. And let’s not forget Wareheim’s unforgettable, magisterially NSFW collaboration with fellow Heavy Light contributor and Gary Panter collaborator Devin Flynn.

Yeah, most of these guys are playing it either for laughs or for sheer mind-melting overload, but I think there’s frequently beauty in there to rival what some of the musicians are doing. (Click again on that first Ben Jones link.) And (thank you Internet God) this amazing video by Peppermelon shows that you can do action, awe, even sensuality with this aesthetic. The rawness, the brightness, the willingness to let the seams show–it all gives you something to push against again.

When I’ve written about The Dark Knight Strikes Again I’ve been fond of saying it was years ahead of its time. Sometime in the past week and a half or so, there was a day when I listened to Washed Out, then stumbled across that Deitch show link in an old bookmark, then watched an episode of Tim & Eric, then came across that Ben Jones WTWTA strip–and suddenly I realized I was right! Not that it matters–at all–whether or not Miller and Varley have any real continuity with any of this material. They certainly didn’t get there before Paper Rad, unless I’m wildly mistaken. But then half the fun of DKSA is spotting all the stuff Miller does, from naked newscasters to superheroes ruling the earth rather than just guarding it, seemingly without realizing someone’s done it first. What difference would that make? Meanwhile, in all the off-the-beaten-path references Frank Santoro has cited during the production of his Ben Jones collaboration Cold Heat–essentially a glo-fi comic book–I haven’t heard word one about this book. But I’m not saying Miller & Varley paved the way for anything. I’m saying that when Miller abandoned his chops (and, for the most part, backgrounds!) for the down and dirty styles he (thought he) saw at SPX, and when Varley decided to use photoshop to call attention to itself rather than to create a simulacrum of something else, they were using the same tools, tapping the same vein, seeking the same sense of excitement, discovery, and trailblazing as these newer movements.

I’ve also been fond of likening DKSA to proto-punk, taking a cue from Tony Millionaire’s jacket-wrap blurb: “Miller has done for comics what the Ramones et al have done for music. This book looks like it was done by a guy with a pen and his girlfriend on an iMac.” The idea is that it’s raw, it’s loud, it’s brash, it doesn’t have time for the usual niceties–it’s getting comics back to their primal pulp roots. I spoke to Miller several times during and following the release of the book, one time for print, and he said as much. (I certainly never would have bought the cockamamie idea that this thing was some sort of corporate cash-grab even if he’d never said word one.) He even mentioned to me his belief that the brightly colored costumes of the early superheroes served mainly the dual purpose of a) telling them apart from one another, and b) proving they weren’t naked, so even his thinking in historical terms had him ready to peel back from realism as a form of reclamation. And of course it’s not exactly like the story was at all subtle in this regard: Batman and his army came back to overthrow the dictators that kept us fat and happy and turned the superheroes into boring wimps. But ultimately the punk comparisons were just a little off. Born less of despair than of delight, filled less with anger than with joy, The Dark Knight Strikes Again anticipated a way of doing things that is not intended to look or sound effortless, that draws attention to its own construction, but which–with every pixelization and artifact, with every crayolafied visual and left-in glitch, with every burbly synth and sky-bright color–pushes against that construction and springs out into something wild and wonderful.

Comics Time: All-Star Superman

February 11, 2011All-Star Superman Vols. 1 & 2

Grant Morrison, writer

Frank Quitely, artist

DC, 2008-2010, believe it or not

160 pages each

$12.99 each

Buy them from Amazon.com

Originally posted on March 11, 2010 at The Savage Critic(s).

The cheeky thing to say about the brand-new out-of-continuity world Grant Morrison constructed to house his idea of the ideal Superman story is that it’s very much like the DC Universe we already know, but without backgrounds. Like John Cassaday, another all-time great superhero artist currently working, Frank Quitely isn’t one for filling in what’s going on behind the action. One wonders what he’d do with a manga-style studio set-up, with a team of young, hungry Glaswegians diligently constructing a photo-ref Metropolis for his brawny, beady-eyed men and leggy, lippy women to inhabit.

But, y’know, whatever. So walls and skyscrapers tend to be flat, featureless rectangles. Why not give colorist/digital inker Jamie Grant big, wide-open canvases for his sullen sunset-reds and bubblegum neon-purples and beatific sky-blues? We’re not quite in Lynn Varley Dark Knight Strikes Again territory here, but the luminous, futuristic rainbow sheen Grant gives so much of the space of each page–not to mention the outfits of Superman, Leo Quintum, Lex Luthor, Samson & Atlas, Krull, the Kryptonians and Kandorians, Super-Lois, and so on–ends up being a huge part of the book’s visual appeal. And thematically resonant to boot! Morrison’s Superman all but radiates positivity and peace, from the covers’ Buddha smiles on down; a glance at the colors on any given page indicates that whatever else is in store, it’s gonna be bright.

Moreover, why not focus on bringing to life the physical business that carries so much of the weight of Morrison’s writing? The relative strengths and deficiencies of his various collaborators in this regard (or, if you prefer, of Morrison, in terms of accommodating said collaborators) has been much discussed, so we can probably take it as read. But when I think of this series, I think of those little physical beats first and foremost. Samson’s little hop-step as he tosses a killer dino-person into space while saying “Yo-ho, Superman!”…Jimmy Olsen’s girlfriend Lucy’s bent leg as she sits on the floor watching TV just before propositioning him…clumsy, oafish Clark Kent bumping into an angry dude just to get him out of the way of falling debris…the Black-K-corrupted Superman quietly crunching the corner of his desk with his bare hands…Doomsday-Jimmy literally lifting himself up off the ground to better pound Evil Superman’s head into the concrete…the way super-powered Lex Luthor shoulders up against a crunching truck as it crashes into him…the sidelong look on Leo Quintum’s face as he warns Superman he could be “the Devil himself”…that wonderful sequence where Superman takes a break to rescue a suicidal goth…Lois Lane’s hair at pretty much every instant…You could go whole runs, good runs, of other superhero comics and be sustained only by only one or two such magical moments. (In Superman terms, I’m a big fan of that climactic “I hate you” in the Johns/Busiek/Woods/Guedes Up, Up & Away!) This series has several per issue.

And the story is a fine one. Again, it’s common knowledge that rather than retelling Superman’s origin (a task it relegates to a single page) or frog-marching us through a souped-up celebration of the Man of Steel’s underrated rogues gallery (the weapon of choice for Geoff Johns’s equally underrated Action Comics run), All-Star Superman pits its title character, directly or indirectly, against an array of Superman manques. The key is that Superman alternately trounces the bad ones and betters the good ones not through his superior but morally neutral brains or brawn, though he has both in spades, but through his noblest qualities: Creativity, cooperation, kindness, selflessness, optimism, love for his family and friends. I suppose it’s no secret that for Morrison, the ultimate superpower of his superheroes is “awesomeness,” but Superman’s awesomeness here is much different than that of, say, Morrison’s Batman. Batman’s the guy you wanna be; Superman’s the guy you know you ought to be, if only you could. The decency fantasy writ large.

Meanwhile, bubbling along in the background are the usual Morrisonian mysteries. Pick this thing apart (mostly by focusing on, again, Quitely’s work with character design and body language) and you can maybe tease out the secret identity of Leo Quintum, the future of both Superman and Lex Luthor, assorted connections to Morrison’s other DC work, and so on. But the nice thing is that you don’t have to do any of that. Morrison’s work tends to reward repeat readings because it doesn’t beat you about the head and neck with everything it has to offer the first time around. You can tune in for the upbeat, exciting adventure comic–a clever, contemporary update on the old puzzle/game/make-believe ’60s mode of Superman storytelling in lieu of today’s ultraviolence, but with enough punching to keep it entertaining (sorry, Bryan Singer). But you can come back to peer at the meticulous construction of the thing, or Morrison’s deft pointillist scripting, or the clues, or any other single element, like the way that when I listen to “Once in a Lifetime” I’ll focus on just the rhythm guitar, or just the drums. Pretty much no matter what you choose to concentrate on, it’s just a wonderfully pleasurable comic to read.

Comics Time: Various pieces by Uno Moralez

February 9, 2011Various comics and illustrations by Uno Moralez

Uno Moralez, writer/artist

self-published, 2011-

Read them for free at UnoMoralez.com

I’ve been struggling mightily to put my finger on what the art and comics of Uno Moralez remind me of. I got that he draws the faces and figures of his characters to evoke that weird frisson you get when you see commercial illustration from other cultures, where what’s perfectly normal in (say) Eastern Europe or the Indian subcontinent or Southeast Asia or Central America looks just slightly off-kilter and disconcerting to us. And I got that he paces his horror comics with the attention to narrative economy and rhythm of a dark Nick Gurewitch. (That comic about the kid and his telescope gave me panicky giggles with each subsequent reveal.) And I got that there’s a massive, in-your-face dose of kink and smut, tying it to similar traditions in Japanese illustrations and comics and also reinforcing that “I shouldn’t be seeing this” feeling. But that weird, glitchy computer drawing style — what is that all about? Then it hit me: It looks like a black-and-white version of the still images they used as cut scenes in old 8-bit Nintendo games. It feels wrong to apply that aesthetic to these horrific images and stories; and because the style is so mechanical, it’s a wrongness that feels as though it has settled into and infected the very digital medium conveying it — the computer equivalent of Pim and Francie‘s Golden Age animation studio gone horribly wrong. Put it all together and you’ve got one of the most impressive and fully formed horror aesthetics I’ve seen…well, since Michael DeForge, I suppose, coupled with that same “whoa” factor I got from the format and pacing of Emily Carroll’s brilliantly assembled “His Face All Red.” Jeepers creepers, does this person hit my buttons.

(Via Zack Soto via Jillian Tamaki via Ryan Sands)

Comics Time: Squadron Supreme

February 7, 2011Squadron Supreme

Mark Gruenwald, writer

Bob Hall, Paul Ryan, John Buscema, Paul Neary, artists

Marvel, 1985-1986 (my collected edition is dated 2003)

352 pages

$29.99

Buy it used from Amazon.com

Originally posted on August 10, 2009 at The Savage Critic(s).

I don’t know what it is about Squadron Supreme, but I seem to read it only during times of great personal trauma. I first read the book in 2003, during my wife’s hospitalization at a residential treatment facility for eating disorders. I have vivid memories of sitting at a nearby Panera Bread between visiting hours, slowly turning the pages. And as I reread the book over the past couple of weeks, an 11-month period during which my wife suffered two miscarriages was capped off by the news that one of my cats has a chronic immune-system disease, complications from which prevented him from eating; our other cat had a cancer scare; both of our cats required major surgery; and one of my wife’s best friends lost her sister-in-law, her niece, and all three of her very young children in a catastrophic car accident that left three other people dead as well.

So it’s entirely possible that as effective and affecting as I find Mark Gruenwald’s magnum opus, my real life is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. Certainly there are a couple of very different ways to read this, arguably the first revisionist superhero comic available to the North American mainstream. For some people, no matter how interesting Gruenwald’s ideas are in terms of laying out the effects of a Justice League of America-type group’s decision to really make the world a better place by transforming society into a superhero-administered utopia, the execution–art, dialogue, and melodramatic plotting all firmly in the mainstream-superhero house style–cuts it off at the knees. For others, it’s precisely that contrast between the traditional stylistics of the superhero and a methodical chronicling of superheroes’ disastrous moral and physical shortcomings that makes the book work.

Count me in the latter category. Squadron Supreme may have more in common with later pseudo-revisionist works like Kingdom Come than it does with Watchmen in that it obviously stems from a place of great affection for the genre rather than dissatisfaction with it. Heck, even The Dark Knight Returns, which is really a celebration of the superheroic ideal, earns its revisionist rep for a thorough dismantling of the superheroes-as-usual style, something Squadron Supreme couldn’t care less about. No, by all accounts (certainly by the testimonials from Mark Waid, Alex Ross, Kurt Busiek, Mike Carlin, Tom DeFalco, Ralph Macchio, and Catherine Gruenwald printed as supplemental materials here) Mark Gruenwald seems to be working in Squadron as a person who loves superheroes so much that he can’t help but try to find out just how far he can take them. That what he comes up with is so bleak and ugly–nearly half of his main characters end up dead, for pete’s sake–is fascinating and sad. It’s like watching Jack Webb do another season of Dragnet consisting of plotlines from The Wire Season Four: Against America’s broken inner-city school system and grinding cycle of poverty, violence, corruption, and abuse, even Sgt. Joe Friday would be powerless.

Of course, in Squadron Supreme the heroes generally do prove able to conquer humankind’s intractable problems. A combination of the kind of supergenius technology that under normal circumstances only gets used to create battle armor or gateways to Dimension X and the tremendous sheer physical power of the big-gun characters proves enough to end war, crime, and poverty, and even put a hold on death. (The book’s vision of giant “Hibernaculums” in which thousands of frozen corpses are interred until such time as medical science discovers a cure for their condition is one of the book’s great, haunting moments of disconnect between cheerful presentation and radical society-transforming idea.) Gruenwald and his collaborators seem to have no doubt that should Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, the Flash, and the rest of the JLA (through their obvious Squadron analogues) be given the reins of the world, they really could solve all our problems for us.

It’s the methods they’d use to get us there that Gruenwald has doubts about. A Clockwork Orange-style brainwashing for criminals; a Second Amendment-busting program of total disarmament for military, law enforcement, and civlians alike; a takeover of many of the key functions of America’s democratically elected government–despite placing his beloved heroes at the center of these plots, it’s no secret where Gruenwald’s sympathy lies. (To return to the Hibernaculums again, a brief sequence involving “right to die” protestors features some of the book’s most provocative ideas just painted on their placards, eg. “WITHOUT DEATH, LIFE IS MEANINGLESS!!!” Yes, there were three exclamation points on the sign.) Still, Gruenwald backpedals from condemning his heroes for their excesses outright: During the book’s climactic confrontation, as bobo Batman Nighthawk wages a war of words with Superman stand-in Hyperion, the rebel leader reveals his biggest problem with the Squadron’s “Utopia Program” to be his fears over what will happen to it when the golden-hearted Squadron members are gone and someone less worthy takes over their apparatus of complete control. (It’s worth noting that the Squadron gets the idea for the Utopia Project as a solution for the damage they themselves did to the planet while under mind control by an alien tyrant.)

But parallel to the big political-philosophical “What If?” ramifications runs another, more affecting revisionist track. This one focuses on the individual problems and perils of the Squadron members. Some of these flow from the underlying Utopia Project scenario, and about those more in a minute, but other times–a Hyperion clone succesfully impersonating him and seducing the Wonder Woman character, Power Princess, in his place; little-person supergenius Tom Thumb (just barely an Atom analog) dying of cancer he’s not smart enough to cure–Gruenwald simply takes a familiar superhero trope or power set and plays the line out as far as it’ll go. In some cases, such as setting up a fundamental Batman/Superman conflict, making Superman and Wonder Woman an item, explicitly depicting the Aquaman character Amphibian as an odd man out, and dancing up to the edge of Larry Niven’s “Man of Steel, Woman of Kleenex” essay on the dangers of superhero sex, I would guess Gruenwald was for the first time giving in-continuity voice to the stuff of fanboy bull sessions that had taken place in dorm rooms and convention bars for years.

While that’s a lot of fun, it’s the unique touches brought to the material by Gruenwald, shaped into disconcerting images by his rotating cast of collaborators (mostly Bob Hall and Paul Ryan), that get under your skin. Nuke discharging so much power inside Doctor Spectrum’s force bubble that he suffocates himself. The vocally-powered Lady Lark breaking up with her boyfriend the Golden Archer under a suppressive cloud of giant, verbiage-filled word balloons. A comatose character’s extradimentional goop leaking out of him because his brain isn’t active enough to stop it, threatening to consume the entire world until Hyperion literally pulls the plug on his life support system. Power Princess tending to her septuagenarian husband, who she met when she first made the scene in World War II. Hyperion detonating an atomic-vision explosion in his semi-evil doppelganger’s face, then beating him to death. Tom Thumb’s death announced in a panel consisting of nothing but block text, unlike anything else in the series. Amid the blocky, Buscema-indebted pantomime figurework and declamatory dialogue, these moments stand out, strangely rancid and difficult to shake.

Perhaps no other aspect of the book gives Gruenwald more to work with than the behavior modification machine. There are all the ethical debates you’d expect–free will, the forfeiture of rights, the greater good. There’s the slippery slope of mindwiping you saw superheroes slide down decades later, and far less interestingly, in Identity Crisis. But again, the personal trumps the political. The standout among the series’ early, episodic issues is the one in which Green Arrow knockoff the Golden Archer (who has the second-funniest name in the series, after Flash figure the Whizzer) uses the b-mod machine on Black Canary stand-in Lady Lark to make her love him after she rebuffs his marriage proposal. She ends up unable to bear being away from him, her fawning driving him mad with guilt, and even after he comes clean about his deception and is expelled from the team, the modification prevents her from not loving him. Later, the device’s use on some of the Squadron’s supervillain enemies turns them into obsequious allies-cum-servants whose inability to question the Squadron, and moreover to feel anything but thrilled about this, does more to turn your sympathies against the SS than all the gun-confiscation scenes in the world.

Late in the book, another pair of behavior modification-related incidents ups the pathos to genuinely disturbing levels. When b-modded ex-villain Ape X spies a new Squadron recruit secretly betraying the team, her technologically mandated inability to betray the Squadron member by telling on her or betray the rest of the team by not telling on her overwhelms Ape X’s modified brain and turns her into a vegetable. And when Nighthawk’s rebel forces kidnap the mentally retarded ex-villain the Shape in order to undo his programming, his childlike pleas for mercy are absolutely heartbreaking, as is the cruel way in which the rebels repeatedly deceive him in order to advance their aims. The look of panic on his face as he shouts “Don’t hurt Shape please!” is tough to stomach.

What it reminds me of more than anything is taking an adorable stuffed animal that you love and throwing it in the garbage. Do you know that feeling? This is not a sentient creature, it does not and cannot interact with you in any real way–and yet you love it. It never did anything to hurt you. Why would you want to throw the poor guy away? No, don’t! By the time you get to the end of Squadron Supreme, a love-letter to the Justice League of America that ends with an issue-long fight that leaves half the participants brutally slaughtered, that’s the feeling I get from the whole book. These superheroes never did anything but bring Mark Gruenwald great joy, he wanted to repay that by doing something unprecedented with them, but as it turns out the unprecedented thing to do was to throw them away.

Comics Time: Spotting Deer and SM

February 4, 2011Spotting Deer

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

Koyama Press, December 2010

12 pages

$5

Buy it from Michael DeForge

SM

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

self-published, December 2010

12 pages

I forget what it cost

“Although physically similar to a common white-tailed deer (Ocoileus virginianus), the spotting deer (Capreolus vulgaris) is actually a kind of terrestrial slug.” So begins the first of two short, creepy comics debuted by Canadian wunderkind Michael DeForge at this past December’s Brooklyn Comics and Graphics Festival, and so does one get a sense of the type of skin-crawly, dis-ease driven horror DeForge is creating here. In the guise of a nature guide, the cartoonist not only piles discomfiting detail (“Its ‘antlers’ are actually colonies of parasitic polyps that are first attached to the deer during adolescence”) upon discomfiting detail (“biologists nickname this phenomenon the ‘sexual acqueduct'”), but trots out a unique and fully formed full-color palette to do so; he then whisks the comic into unexpected territory by making it just as much about the obsessive in-story writer of the guide, whose face we never see even as evidence quietly accrues that his interest in these strange creatures has more or less ruined his life. The self-published SM is similarly based in the horror of the squicky and gross (a snowman stands mutely smiling as two teenagers take a knife to it, unpleasantly revealing that it’s somehow made out of real flesh) and similarly takes off into unpredictable territory (the flesh is hallucinogenic; the snowman’s nearest neighbor is a Texas Chain Saw Massacre-style old man who doesn’t take kindly to trespassers). As if compensating for the comparative lack of color, DeForge makes the book’s centerpiece as sensual as possible: It’s a full-on psychedelic freak-out laid atop a topless makeout session by an ersatz Maggie and Hopey. It’s enough eye candy to send you into the visual equivalent of diabetic shock, which somehow leaves you even better prepared to picture the unpleasantness that goes on between panels on the subsequent page and is about to go on after that elegant final panel. The best part of all, of course, is that while DeForge’s alt-horror idiom is familiar enough (especially to me, especially lately), his personal drawing style isn’t; DeForge’s comics really do look only like themselves. Give me more.

Comics Time: Studygroup12 #4

February 2, 2011Studygroup 12 #4

Zack Soto, Steve Weissman, Eleanor Davis, Michael DeForge, Trevor Alixopulos, T. Edward Bak, Chris Cilla, Max Clotfelter, Farel Dalrymple, Vanessa Davis, Theo Ellsworth, Jason Fischer, Nick Gazin, Richard Han, Jevon Jihanian, Aidan Koch, Amy Kuttab, Blaise Larmee, Corey Lewis, Kiyoshi Nakazawa, Tom Neely, Jennifer Parks, Karn Piana, Jim Rugg, Tim Root, Ian Sundahl, Angie Wang, Dan Zettwoch, writers/artists

Zack Soto, editor

Milo George, editorial/technical advisor

Published by Jason Leivian and Zack Soto, December 2010

80 pages

$20

Buy it from Zack Soto

This is going to come out sounding waaaay more like a diss than it’s intended to, but in flipping through the comeback installment of this Zack Soto-edited alt/artcomix anthology a few weeks after my initial read-through, I realized I didn’t remember anything in it prior to cracking the covers once again. Which is fine, I think! Looking at it now, Studygroup12 #4 seems to me to be much more an art book than a comics anthology. For one thing it’s exquisitely made: Beautiful screenprinted neon-pink-and-aqua covers inside covers (trust me, it’s much glowier than the scan above suggests); a gallery of impactful pink/blue/purple splash pages to kick things off and close things out, including some of the most striking images Jon Vermilyea and Dan Zettwoch have ever constructed out of their customary melty-monster and diagram styles respectively; pages printed in the vivid, inky blue-purple of a carbon copy. It’s a lovely package even compared to the similar approaches of Mould Map and Monster. My point is simply that all these things point to a book that works better from moment to moment as a catalog of images and illustrations rather than one whose strength arises from the cumulative impact of individual sequential narratives. Flipping through, I’m struck by the weird mystical sensuality of Aidan Koch’s portraiture and triangular caption boxes; the Renee-French-on-a-photocopier haze of Jennifer Parks’s creepy little strip; the pleasure of seeing Tom Neely images reproduced at a much larger size than his customary minicomics; the strength of the way Vanessa Davis designs leering faces, something that’s much clearer to me here than its ever been in the comics I’ve seen from her elsewhere, which frankly have never bowled me over the way they have so many readers; some funny punk/thrash/metal/trash pastiches from Vice Magazine’s mustache-at-large Nick Gazin (I wish a HAUNTED HOLOCAUST: “THE TEENAGE TITS TOUR” t-shirt actually existed). But much of what really reads as comics does so rather weakly — an uncharacteristic experimental misfire from Michael DeForge; the return of USApe, my least favorite Jim Rugg character; diminishing returns from Vermilyea’s anthropomorphized breakfast gang, which here get a little too Milk and Cheese-y; a Farel Dalrymple strip that’s drowned out by its over-shading; etc. Ultimately it’s really only Blaise Larmee’s riotously confrontational anxiety-of-influence comic, in which one of his trademark prepubescent/elfin protagonists navigates her way through some sort of abstract geometric maze only to stand in front of a menacing reproduced photograph of Charles Schulz (!!!), that hits me hard as comics; perhaps not coincidentally it’s the first time I’ve seen anything from his whole Comets Comets crew that makes good on their kill-yr-idols gotta-make-way-for-the-homo-superior internet trolling. As a look at the Portland-helmed turn-of-the-decade artcomix look, it’s swell; as a look at their comics, and where they might take everyone else’s, it’s only a start.

Comics Time: Snake Oil #6: The Ground Is Soft

January 31, 2011Snake Oil #6: The Ground Is Soft

Chuck Forsman, writer/artist

self-published, December 2010

56 pages

$7

Buy it from the Oily Boutique