Posts Tagged ‘comics reviews’

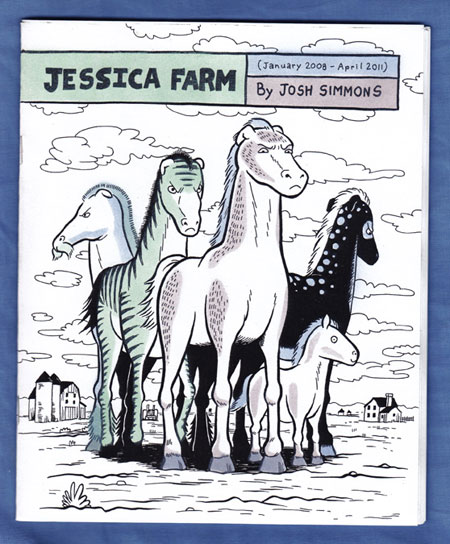

Comics Time: Jessica Farm (January 2008-April 2011)

June 15, 2011Jessica Farm (January 2008-April 2011)

Josh Simmons, writer/artist

self-published, June 2011

40 pages

$8 (including shipping)

Buy it from Josh Simmons

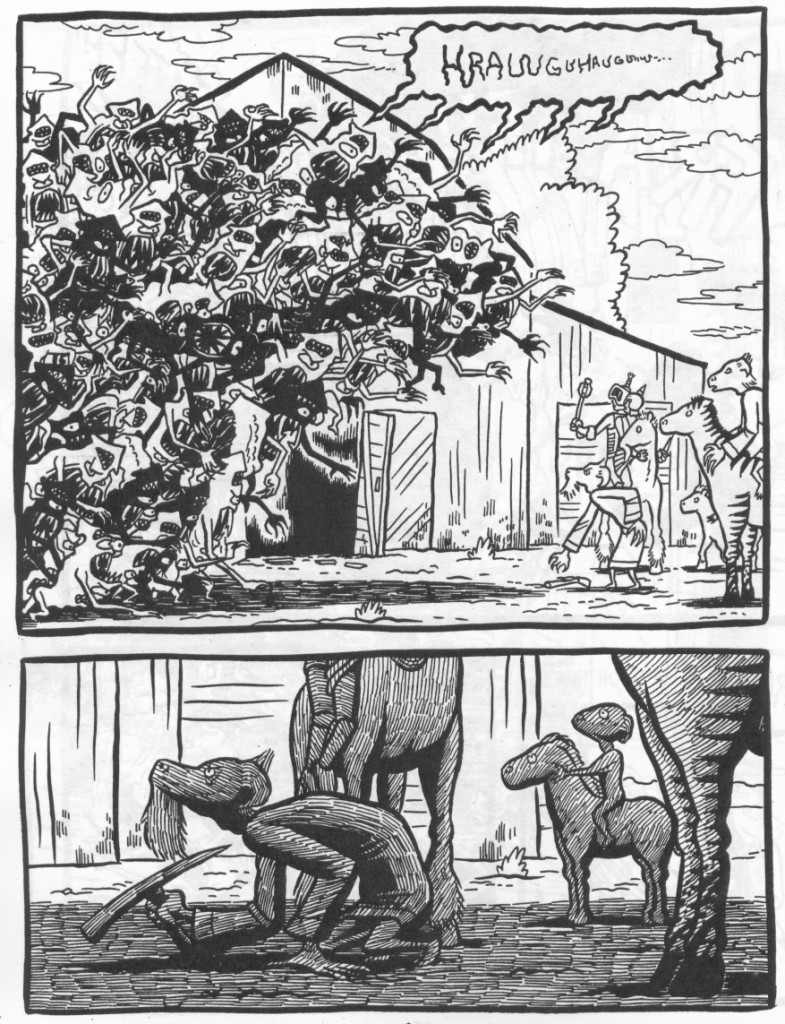

If there’s a cartoonist working today who more reliably, ruthlessly, and relentlessly exploits his own strengths with each new release than Josh Simmons, I’ve yet to encounter him. Witness this self-published slice of Jessica Farm, a 600-page graphic novel Simmons is drawing one page a month for a projected fifty years. Volume One was published by Fantagraphics in April 2008, (the back cover of this minicomic installment reads “Volume 2 coming 2016”), and already the contrast with the involving but formless original is striking. Instead of taking us on sort of “It’s a Small World” ride through various disconnected images of dreamlike horror and weirdness, Simmons here uses his rubric of a teenage girl meeting strange invaders and residents on the sprawling family estate to keep us rooted to the same two places: a bare room where a trio of goat-people called the Smiths are brutalizing a boogeyman akin to the one that Jessica encountered in Vol. 1, and the field outside where they eventually do battle with an army of the creatures. The book feels much more focused for the lack of literal wandering. Moreover, within these established confines, Simmons can get much more mileage out of his astutely choreographed action sequences. In the first half of the book, two dramatic attacks are dependent on our feel for how large the room is and how long it takes characters to get from one side to the other, and Simmons crafts that space so well that you can practically hear the scrambling footfalls. A later sequence involves charging horses and bounding beasts, depicted in a succession of widescreen panels that keep the action dead center in each one, a restrained presentation of very visceral material.

And I don’t know how it’s possible, but the pacing is remarkable for a book drawn with thirty days between each page. It’s reversal after reversal: These Smiths are scary, no wait, they’re friendly; they’ve got the upper hand on their captive, no wait, it’s got the upper hand on them, no wait, I was right the first time; they’re attacking a couple of monsters, no wait, they’re outnumbered a hundred to one, so what, they’re still going to win. It has a propulsive feel to it that Vol. 1 lacked.

Simmons’s usual talents are in evidence here as well. From the title creatures in “Night of the Jibblers” and “Jesus Christ” to the witches and ogres of “Cockbone” to the Godzilla-sized pink slug in The White Rhinoceros, he’s developing one of the best bestiaries in comics, and the “skrats” at the center of this story fit right into that menagerie. They come in black and white varieties here, and in great numbers by book’s end, allowing Simmons’s ever smoother inks (reproduced beautifully here, by the way) to evoke everything from Spy vs. Spy to David B. to that Escher drawing with the fish and the birds. And like most of Simmons’s monsters, they’re a discomfiting combination of flesh and fangs that makes you feel that being attacked by one of them would be not just deadly but grotesquely intimate, like being mauled by a giant scrotum studded with razor blades. The characters we meet are similarly creepy, using Simmons’s standard and still unnerving combination of over-the-top aw-shucks friendliness and violent, obscene threats and exclamations, like a beloved uncle you suddenly realize you don’t want to be alone with anymore. Lovely cartooning, icky horror, and a battle scene that’ll likely top anything else you see this year, for eight dollars total? No way you should wait till 2016.

Comics Time: Cindy and Biscuit

June 13, 2011 Cindy and Biscuit

Cindy and Biscuit

Dan White, writer/artist

Milk the Cat, 2011

24 pages

£2.50

Buy it from Milk the Cat

What a pleasant surprise this turned out to be. Created by Dan White, aka The Beast Must Die from the Mindless Ones blog, Cindy and Biscuit has a look that at first glance might tempt you into thinking it’s one of those try-too-hard “bang! pow! comics aren’t just for grown-ups anymore!” all-ages things that grown-ups on the Internet really like — but only at the very first and most cursory glance. Take a closer look at that cover: It’s not just a spunky-lookin’ little girl and her plucky canine companion, it’s also a mountain of skulls and a board with a nail through it. Things never get quite that grim inside, but it still comes as something as a shock when our dynamic duo spots an alien landing crew and, instead of having some zany spooky adventure, Cindy leaps through the air and brings her board down on an alien’s head with full force, shattering the helmet into tiny safety-glass fragments and smashing the head to a pancake with a KKRUNNT! (Great sound effect, by the way.) That’s the moment where it becomes apparent that White will be bringing to the surface all of the unpleasantly unrestrained id lurking beneath fondly remembered all-ages entertainments from Calvin & Hobbes to Bone. In addition to going Game of Thrones on those aliens, the three stories collected here see Cindy stumbling across a savage, slavering werewolf only to be patted on the head by the beast, who’s seemingly acknowledging a kindred spirit, and recounting a dream in which she floats to the Moon and tosses a rock at the Earth, blowing it up. White realizes that the danger we crave as kids is a projection of the dangerous sensations called up by our own anger and frustration with a world we’re quickly learning is unfair. The best thing about Cindy and Biscuit, though, is that it really could be an all-ages comic, and an excellent one at that. White’s thick line has a candy-like quality to it, wavy and chunky and almost chewy, and which gives his rather impeccable action shots real heft and momentum. He draws Cindy as a bounding presence whose feet stay a solid foot and a half in the air when she runs, but she doesn’t come across as weightless or effortless, but rather as a physical thing that’s got so much energy behind her she’s propelling herself off the ground. Biscuit’s a good design too, like an arrow in dog form. It’s solid enough in terms of figurework and depiction of action to put me in mind of a less claustrophobic Brian Ralph, while the use of a genuinely fun adventure-comic look and tone to say something melancholy about youth is reminiscent of sweet-and-sour “new action” books from Street Angel to Cold Heat. It’s easy to imagine a big color collection of these with a few more uncompromising little stories added in really knocking people for a loop. It’s well worth a look as is — an intriguing array of visuals and ideas from a talented off-the-radar cartoonist.

Comics Time: Prison for Bitches

June 10, 2011Prison for Bitches

Ryan Sands, Hellen Jo, Calivn Wong, Anthony Ha, Makkinoso, Gea, Sophia Foster-Dimino, Chris Kuzma, Johnny Ryan, Sophie Yanow, Chris “Elio” Eliopoulos, Michael Kupperman, Adam Bronson, An Nguyen, Mickey Zacchilli, Lisa Hanawalt, Anthony Wu, Evan Hadyen, Leslie Predy, Monika Uchiyama, y16o, Ryan Germick, Saicoink, Angie Wang, Tony Tulathimutte, Andre Syzmanowicz, Raymond Sohn, Michael DeForge, Mia Shwartz, Patrick Kyle, Derek Yu, Jordyn Bochon, Seibei, Ginette Lapalme, Nick Gazin, Harvey James, Zejian Shen, Robert Dayton, Aaron Mew, writers/artists

Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge, editors

self-published, 2010

64 pages

$12

Buy it and see an extensive preview at PrisonForBitches.com

The wonderful thing about recruiting a galaxy of underground comics and illustration stars to make a Lady Gaga fanzine is that no matter what kind of extravagant weirdness they concoct, there’s a better-than-even chance that at any moment the Lady herself could come along and comfortably out-weird them all. Nearly to a piece, the art, comics, photography, interviews, and essays assembled here by the Thickness team of Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge appear to have been created with a healthy appreciation for their own potential obsolescence in mind, and admiration and awe for the relentlessly and exuberantly creative young woman who’d make it happen. How else to explain the number of contributions that portray Gaga as godlike? In the hands of the Prison for Bitches team, Gaga is a queen seated on a giant telephone throwing trinkets to the huddled masses (Foster-Dimino); a vision appearing in dreams to espouse Anarcho-Gagaism to her supplicants (Yanow); a Big Brother-style disembodied head whose kohl-rimmed eyes stare at the viewer with a totalitarian sex-death gaze like something out of Metropolis (Kupperman); a She-Ra/ELA-esque figure riding through space atop a crystalline Battle-cat (Hayden); a Ray-Ban-wearing Baphomet (Predy); a giant sea goddess towering over the bodies of the drowned (Wang); an empress who lives to be 110 years old (DeForge); a severed head whose tongue, hair, and blood vessels are Cthulhoid tentacles (Aaron Mew). She is seen as supernatural, both a Delphic oracle of fabulousness and a Ring-claiming Galadriel proclaiming “All shall love me and despair.”

On the “love me” point, only a handful of the contributors work with the fact that she’s a very attractive person, but they’re among my favorites: André Syzmanowicz lovingly depicts the curves of her stomach, her breasts, her armpits, even as a werewolf creature gropes her from behind; a strip from Robert Dayton sees an ostensible fan complain about her mediocre music and ripped-off style, finally responding to the question “What do you like about her then?” with “Her navel—I want to lick her navel”; and right between the staples in the centerfold spread that anchors the book’s central full-color section, Mickey Zacchilli sticks the singer’s famously fit rear end.

Still other contributors take advantage of Gaga’s graphic potential for maximum maximalist imagemaking — artist after artist (Jo, Wang, Gazin, Yu, Bochon, Foster-Dimino) have a ton of fun with her hair, culminating in a spectacular caricature of her Coke-can curlers from the “Telephone” video by Harvey James. An Nguyen and the team of Hellen Jo & Calvin Wong provide concert reportage, the former with photos of her cosplaying fans, the latter with comics about the on- and off-stage spectacle of the concert experience.

A trio of prose pieces appear in what seems like ascending order of skepticism; in descending order, Adam Bronson has a funny piece that uses Deleuze and Hegel to analyze the relative potential of Gaga’s “Let’s Dance” and Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” to provoke violence in Filipino karaoke bars; Anthony Ha interviews Vanessa Grigoriadis, author of New York magazine’s seminal profile of Gaga’s origins and rise to fame, that’s best summed up by its title – “I’m a Total Fan of Hers, I Just Am Not a Huge Fan of Her Music”; editor Sands kicks the whole thing off with an utterly sincere and descriptively, persuasively argued “UNDISPUTED TOP 5 LADY GAGA SONGS,” featuring genuine gems like “[‘Alejandro’] sounds like ABBA’s ‘Fernando’ rubbing lotion all over Ace of Base’s ‘Don’t Turn Around’ while bathing nude on ‘La Isla Bonita'” and “[‘So Happy I Could Die’ is] really just a simple song about being convinced you are the hottest and most desirable person on the earth, and that this can be the best of all possible worlds if we allow ourselves the pleasure.” Taken in tandem, they’re like a debate between different modes of Gaga fandom, from arch irony to measured respect for a pop-culture needle-mover to downright love for someone who makes awesome songs to dance to.

The whole zine works like this, basically. Whatever it is you get out of Gaga — a pop-art deity, a gorgeous girl, an eye-inspiring spectacle, a thinkpiece generator, a hitmaker — by all means share that fun with a world that doesn’t have enough of it. This book is a snapshot of the Gaga conversation, post-“Telephone” video 2010; it’s a testament to the contributors and their subject alike that even now that the specifics of that conversation have now been rendered moot by an album full of pinball music and Clarence Clemons sax solos with a cover that reads “BORN THIS WAY” over a picture of the artist as a motorcycle with a human head, I’d love to hear them have it all over again. Prison for Bitches is a Little Monster must-have for any Gaga fan.

Comics Time: Thickness #1

June 8, 2011Thickness #1

Katie Skelly, Jonny Negron, Zejian Shen, Derek Ballard, True Chubbo, writers/artists

Ryan Sands and Michael DeForge, editors

self-published, May 2011

48 pages

$12

Buy it from the Thickness website

The great altcomix fuckfest continues! Of the recent releases I’ve read that pass smut through the same art-comics filter that science fiction, fantasy, action, and horror have all recently traversed, Thickness is the book that seems most concerned with creating out-and-out pornography. Chalk that up primarily to the anthology’s centerpiece and unquestionable standout, “Grandaddy Purple, Erotic Gameshow,” by cover artist Jonny Negron. “Dreamlike” is an adjective that gets tossed around a lot, by me not least of all, but that’s absolutely the right way to describe the plot of this thing, which starts with two sinister gangster-type figures falling victim to a rooftop assassination, then follows the assassin as he’s rewarded with a Let’s Make a Deal selection of prizes hidden behind three numbered doors, then shows him claiming his prize — a beautiful woman — in explicit detail, and ends with his post-climax black-widow murder. Negron can’t seem to contain his glee during the sex scene: The woman shouts out no-fuckin’-around, let’s-have-fun-with-our-bathing-suit-area exclamations like “Mmm, let’s see how much I can fit in my mouth!” and “Fuck! We’re goin’ to have fun with this cock!”, while Negron frequently breaks down his large panels into sub-grids of as many as nine, 10, or 11 panels, using the layout language of Acme Novelty Library to cram in as many of the deliciously dirty details of the characters’ liaison as possible before running out of room on the page. To quote Maude Lebowski, sex in Negron’s hands is a zesty enterprise. But it’s just one of the arrows in his quiver: His story also features angular artificial environments and M.U.S.C.L.E.S.-style character designs that, when combined with his women’s King magazine physiques and his bad guys’ skinny-suit-and-shades-sporting comportment, makes him come across like a happy marriage of Yuichi Yokoyama and Benjamin Marra. His depiction of action is really a marvel, too: It can be dynamically staged as all get-out, but then he does something off-kilter, like showing a falling man’s impact with the floor and his subsequent post-mortem prostration in a fashion that totally flattens the moment, calls attention to its ludicrousness, and yet somehow makes it feel all the more brutal and unpleasant for that. Ditto the final image, which I won’t spoil.

By comparison the other contributions can’t help but feel slight. Katie Skelly’s “cute-sexy floppy-eared lady has sex with plants in a sci-fi paradise that suggests Vaughan Bode mated with Georgia O’Keefe” entry “Breeding Season” is covering well-worn territory for SF erotica, though her thick rounded inks are nice to look at and she has a knack for capturing certain visual details that entice, like the gap between the fabric of the heroine’s suspender-like bathing suit and her breast and torso when viewed from the side. Zejian Shen’s “Pearl Divers” wrings an amusing dual joke out of its title’s double entendre by anthorpomorphizing both the oysters captured by the titular fisherwomen and their clitorises as they celebrate their catch with some beachside tribadism. Derek Ballard’s “Trap Shadez” is another sci-fi story whose sexual content is actually relatively minimal; for my taste it overelies on angular ’80s-tinged figurework and design that can’t quite overcome storytelling that’s deliberately but still unsuccessfully unclear. The True Chubbo comic that closes out the collection is a solid example of that strip’s unusual charm (it’s more charming than funny), wherein the love between creators Ray Sohn and his anonymous wife comes through all the clearer the worse their ridiculously violent sexual violations of one another get. Sands and DeForge’s high-quality production, including risograph printing that gives each story a fitting primary color ink, certainly elevates each contributor — the murky purple selected for Negron makes that particular freakout even seedier, somehow. He’s worth the price of admission all by himself, and hey, a home run after four singles still puts a lot of runs on the scoreboard.

Comics Time: Sock

June 6, 2011Sock

Chris Day, Conor Stechschulte, Mr. Freibert, Matthew Thurber, Neal Reinalda, Molly O’Connell, Emily Johnson, C.F., Zach Hazard Vaupen, Sam Gaskin, Ben Stiegler, Erin Womack, writers/artists

Conor Stechschulte, editor

Crepuscular Archives, May 2011

40 pages

$6

Buy it from Closed Caption Comics

In which the Closed Caption Comics crew and selected associates get freaky. Billed on the cover as a collection of “ADULT STORIES AND IMAGERY,” Sock proceeds in the mighty CCC manner, albeit a pornographic variant thereof. Editor Conor Stechschulte and Noel Freibert go in their customary horror direction, with Stechschulte employing a less dense than usual style for an Evil Dead referencing story of a woman sliding down a hill while being taken advantage of by the flora, and Freibert using his customary in-your-face explicit dialogue (“I’m just experimenting with the corpses, running tests”) and gutterless panel layouts for a “straight forward sex-death comic” that relies equally on puns (holes, bones, and boxes figure prominently) and dream logic to conflate the two impulses. The flipside to their ugliness is elegance, and here’ it’s provided by Chris Day’s almost rebus-like typography and decontextualized presentation of sexual imagery (a whip, a boot, a big black circle, the legs and crotch of a woman in black underwear and garters); one of C.F.’s always convincingly delivered portraits of women in bondage, all thin lines, bound breasts, tile floors, and lovingly delineated spit; and a wordless, benday-day dotted strip from Erin Womack, which convincingly uses corn cobs and ropes and fountains in tandem with drawings of figures in embrace and ecstasy as stand-ins for the more explicit stuff found elsewhere in the anthology. Zach Hazard Vaupen even gets a good gag strip out of the idea of anal sex, which you’d think would be impossible in our assfucking-fatigued society. None of this is a turn-on per se — erotica it may be, but pornography, then, not so much. However, its most effective contributions earn that honor by coming across as genuine transmissions from artists about what they consider sexy, from Day and Womack and C.F.’s poetically understated images to a simple, funny pin-up from Neal Reinalda that simply puts a photo of Nicki Minaj and her cartoonish physique back(side)-to-back with a drawing of Jessica Rabbit. A wise woman once asked, “What do you consider fun?”; when it works, Sock answers.

Comics Time: Too Dark to See

June 3, 2011Too Dark to See

Julia Gfrörer, writer/artist

Thuban Press, May 2011

32 pages

$5

Buy it from Julia Gfrörer

Buy it from Sparkplug

“I just need your cum. Give it to me and I’ll go away.” Well, hello, sailor! In the vanguard of a burgeoning mini-movement of alternative comics dealing frankly and explicitly with/in sex, Too Dark to See centers on a liaison between a sleepy (or possibly sleeping) young man and a spectral shadow woman, the bluntly transactional nature of which is no doubt hot to some, cold to others. It’s tough to figure out how to feel about it, actually, and that’s what makes it a fine catalyst for the story, which is primarily about the real live human couple of which the guy is a part. His girlfriend, our protagonist through the bulk of the story, is introduced to us as either she or he (it’s not clear who; I’m not sure it matters) says “No one has ever loved anyone more than I love you” as they embrace in bed, but before long she’s being cuckolded by a shadow creature. We next see her sitting on the toilet, naked from the waist down, awkwardly asking the guy if he remembers jerking off in his sleep. She’s at a disadvantage throughout: She thinks her boyfriend might be cheating on her and her suspicion is greeted with angry dismissal, she fails to pick up on cues he thinks are screamingly obvious and interrupts him as he works on writing “the first good idea I’ve had in ages,” she suspects a customer at the coffee shop where she works of coming in solely to judge her, she’s worried about a black spot that could be an STD but which we can gather from our experience with the shadow person is likely something far more sinister, she self-mutilates, she struggles to even be heard at one point while lying under the covers when her boyfriend returns after storming off, and even supernatural entities make fun of her. Factor in Gfrörer’s shaky, wiry line, really perfect for capturing both the undermployed bohemian demimonde and the veal-calf physicality of young skinny naked people, and the feeling that emerges is one of almost overwhelming vulnerability — a woman who feels at the mercy of love, sex, money, class, and her own body, to the point where the addition of dark forces from beyond feels not just appropriate but almost inevitable. It’s an ugly feeling, and it takes a special sort of beauty to capture it as well as this disarming little comic does.

Comics Time: Open Country #1

June 1, 2011Open Country #1

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

self-published, May 2011

16 pages

Read some preview pages, and buy it eventually, I’d imagine, at Michael DeForge’s website

I think there’s a greatest-hits compilation called A Young Person’s Guide to King Crimson? That’s sort of what this is for Michael DeForge. Nearly all his themes can be heard here: deadpan slice-of-life dialogue juxtaposed with extravagantly odd SFF concepts; deconstructed, dismantled, dismembered, disfigured human bodies and faces, like cubism reimagined as body horror; friendship depicted primarily as a venue for venting ideas and concerns at one another rather than real emotional interaction; uncomfortably accurate and funny lampooning of the disconnect between lofty art-school philosophizing and post-graduation economic reality; visually spectacular treatment of altered states shared by two people; creepy horror slowly oozing out of and eventually overwhelming previously established ideas. Conspicuously absent are the full-fledged rubble-strewn wastelands of the sort seen in Lose #3, but in their place there’s a conversation about such post-apocalyptic landscapes. It comes in the context of an interview with the visual artist whose work is the catalyst for the comic. She works in the medium of psychic projection, said by our leading man to be the province of the educated and access-granted elite: “Sometimes I wish I had actually stayed in art school so I could have learned how to do that sort of thing. There are so many techinques that I don’t have the time or resources to learn on my own…psychic projection, silkscreening, linocuts, darkroom photography–all that stuff.” Our hero tries to bone up on the form by watching an interview with the artist (whom we first see as she projects an avatar of herself that’s gigantic, nude, impaled in a field of debris, and begging for help) on YouTube: “[Do you] really believe that? That there’s ‘nothing left to build on?'” asks her interviewer. “Your imagery is so preoccupied with debris, clutter, refuse…'” This might as well be an interview with DeForge himself. And like a good interview, Open Country #1 is a great thing to hand someone who wants to see what’s up with the artist in question.

Comics Time: SF #1

May 30, 2011SF #1

Ryan Cecil Smith, writer/artist

Closed Caption Comics, May 2011

36 pages

$5

Buy it from Ryan Cecil Smith

I know, I know, “Physician, heal thyself,” but I was skeptical of the need for another altcomix take on space opera. Closed Caption Comics member Ryan Cecil Smith is at his best when he’s riding his preoccupations into uncharted territory, be it his high-camp horror-manga riff Two Eyes of the Beautiful or his wild “bicycling action as you like it!” adventure “Koshien: Impossible.” But anthorpomorphic alien races, laser guns, intergalactic law enforcement agencies, worldbuilding, and knowingly arch dialogue are a commonplace even in revisionist circles. Would Smith bring enough new ingredients to the table to get me to eat it? I needn’t have worried. Taking advantage of a larger trim size and pretty high quality printing for a minicomic, SF gives Smith an expansive canvas on which to deploy a take on sci-fi swashbuckling that’s…quietly silly, if that’s even possible. His line feels light and frothy here, a fluid thing that flows along with the propulsive action sequences (a shootout in a hospital is particularly bombastically staged) and the charming character designs (aliens variously evoke the creature-people of Lewis Trondheim, James Kochalka, and Chris Wright, while our hero Ace of the Space Fleet Scientific Foundation Special Forces has a giant mountain of hair that wouldn’t look out of place in Dragonball-Z, a demeanor akin to one of Naoki Urasawa’s indefatigable ultra-awesome do-gooder detectives, and a laser gun that would give that dude from Berserk and his sword a run for their collective money on any Freudian analyst’s couch.) Zipatone-style shading gives the art dimension while obviating the need for Smith to vary his lineweight overmuch and thus lose some of its elegance. And as simplistic as it is, the story even manages to be engaging, with its tale of a boy orphaned by terrorist space pirates and taken under the wing of the galaxy’s greatest gang of good guys — if I didn’t have this exact fantasy while in grade school, I had one so similar that it hardly makes a difference. Surely the mark of a successful exercise in genre is that whatever pleasure the reader derives from seeing generic tropes exploited or subverted places second behind simply wanting to see what happens next. That’s where I’m at with this one.

Comics Time: Mister Wonderful

May 27, 2011Mister Wonderful

Daniel Clowes, writer/artist

Pantheon, April 2011

80 pages, hardcover

$19.95

Buy it from Amazon.com

Oddly enough for a book that numbers among his most accessible — brief, funny, light, with an ending that doesn’t make you want to throw yourself out a window — Mister Wonderful really works best if you’ve read enough Daniel Clowes to realize just how different it is. When you’ve met Andy the Death-Ray and Wilson, our main character Marshall seems like a pussycat even at his most judgmental or self-lacerating. When you’ve experienced the bleak, paranoid claustrophobia of Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron or David Boring, or for that matter the misanthropic rant-based humor of “Sports” or “Art School Confidential,” a rom-com/comedy of discomfort mash-up feels all the more sunny and breezy even at its blackest. When you’ve read comics assembled from individual strips drawn in a multiplicity of styles like Ice Haven or The Death-Ray or Wilson, both Mister Wonderful‘s original “Tune in next week, same Clowes-time, same Clowes-channel!” incarnation as a serialized strip in The New York Times Magazine and its re-cut, re-edited, expanded, much less punchline and cliffhanger dependent reincarnation here come across like a study in stylistic and storytelling economy. When you’ve seen how much mileage Clowes gets out of the cramped feel of his pages and the studied ugliness of their contents — even at their prettiest his comics have the uncomfortable, slightly awkward feeling of wearing a suit that’s a size or two too small — watching him blow out images to sprawl across both pages of a loooooong horizontal spread is a glorious thing indeed, infusing the images so selected with emotional power, whatever emotion it happens to be at the time. And when you’ve seen Ghost World‘s seemingly optimistic yet decidedly ambiguous ending, Mister Wonderful‘s denouement becomes all the more notable, both for its similarities (a bench figures prominently in both) and its differences (Ghost World‘s bench is empty, Mister Wonderful occupied and shared). It’s the differences that make all the difference.

Click here for an interview I conducted with Clowes about the book.

Comics Time: Closed Caption Comics #9

May 25, 2011Closed Caption Comics #9

Pete Razon, Lane Milburn, Conor Stechschulte, Mr. Noel Freibert, Ryan Cecil Smith, Chris Day, Erin Womack, Andrew Neyer, Mollie Goldstrom, Molly O’Connell, Zach Hazard Vaupen, writers/artists

Closed Caption Comics, December 2010

192 pages

$20

Buy it and see preview pages from every contributor at Closed Caption Comics

My favorite thing about the men and women of Closed Caption Comics is how much about their ways of drawing I just don’t get. I don’t get how Lane Milburn builds these beefy sci-fi-fantasy-horror creatures and warriors out of crosshatching and cleverly chosen angles and a line thick enough to look like it was drawn with a Crayola marker held in a fist. I don’t get how Conor Stechschulte creates his black images and blacker stories with lines piled upon wispy lines. I don’t get the thought process behind Mr. Freibert’s scraggly uniform-line-weight EC pastiches, with their abstract-lettering (???) interludes and endings that aren’t so much the usual O. Henry-by-way-of-the-Cryptkeeper twists but just the most ludicrously dark way the story could go. I don’t get Chris Day’s blend of chopped-up images, geometric shapes, block printing, and murky visual noise, and how it somehow fits so well with an elliptical tone poem about how The ’60s as a cultural force (from Marilyn to Manson) were a Satanic plot. I don’t get Andrew Neyer’s lightly penciled cross between a children’s storybook and a lo-fi Yuichi Yokoyama comic, its gutterless panel grids producing cross-image tangents that can be read as pure imagemaking in a way that belies his childlike character designs. I don’t get Molly O’Connell’s crazily ornate yet somehow messy figurework, her people who look like they were built out of tiny feathers. I don’t get how Zach Hazard Vaupen’s stuff doesn’t so much spot blacks as pour and smear them all over everything, reducing legibility but somehow increasing communicative power. Even the things I do think I can understand, like Ryan Cecil Smith’s cartoony parable, Mollie Goldstrom’s staggeringly detailed exploration of snowfall, Stechschulte’s painstakingly photorealistic drawings of a forest, Erin Womack’s elegantly iconographic tale of mystical violence, or Pete Razon’s knockout cover (which couldn’t speak more directly to me if it could literally talk), feel as though they emerged from a thoughtspace I could never quite access on my own, even if I recognize their results. That’s why I keep coming back to what they put out every time I see their table at a show, snapping up minicomics and eyeing their more expensive objects enviously. I don’t know where they’ll take me, but I know I’ll want to go there.

Comics Time: Gaylord Phoenix

May 23, 2011 Gaylord Phoenix

Gaylord Phoenix

Edie Fake, writer/artist

Secret Acres, 2010

256 pages

$17.95

Buy it from Secret Acres

Buy it from Amazon.com

Well now, here’s a pleasure: a book that gets steadily better as it goes on, so much so that by the time you finish it it’s as though you’re reading a second, later, better book by the same author. In some sense that’s literally true: Cartoonist Edie Fake serialized the story in the minicomic series of the same name over the course of years, so you’re seeing the work of an older, more experienced artist by book’s end. But his artistic growth isn’t just a “well hey, good for him” situation, it’s a happy complement to the growth of the wandering, questing title character. Watching Fake’s art tighten up — his placement of the characters on the page become more self-assured, his pacing become more controlled, his blank white pages fill up with elaborate psychedelic vistas and bold dot or grid textures and lovely two-tone color — does as much to show us his hero’s maturation as anything the character himself does or says or sees.

Like Kolbeinn Karlsson’s The Troll King, Gaylord Phoenix talks about homosexuality using the narrative language of myths and monsters with a pronounced art-comics accent. We first meet the Gaylord Phoenix (who’s a dome-headed, tube-nosed naked dude and not a phoenix at all) as he is about to be attacked by a crystalline monster; he survives the attack, but the wound he sustains carries within it an infection of aggression that eventually drives him to kill his lover. When the slain man is revived at the behest of a subterranean crocodile emperor, the phoenix returns to claim him, but the lover uses the magic now present inside him to cast the phoenix away. What follows is a journey consisting of encounters with various creatures and beings seeking to use the phoenix for their own ends, leading to sex, violence, enlightenment, and sometimes all three.

Fake is a lateral thinker when it comes to devising ways to depict all these things: The result, whether it’s a crocodile tail inserted through the anus and protruding out the mouth, penises that look like giant macaroni and thus can both penetrate and be penetrated, or a multiplicity of cocks that cover a crotch like the tentacles of a sea anemone, is racy, unexpected, a bit weird, and sometimes even a bit scary, which is pretty much how sex ought to be. But aggression is just as central to the story, a fact that’s unfortunate for the characters but a breath of fresh air in how it reclaims the province of traditional masculinity for homosexuality even while preserving queerness’ outsider identity. The climax (no pun intended) further emphasizes the importance of this synthesis, as the Gaylord Phoenix discovers that everyone he’s met on his journey is now literally a part of him, unleashed in what can only be described as the world’s first solo orgy. “It is all with me now,” he proclaims. “At last I hold my own…and partake of who I am.”

The problem with the book, I suppose, is right there: It’s a bit too neatly allegorical to ever truly soar, and its didactic conclusion left me feeling a little too much like I’d just heard the phrase “And the moral of the story is….” I wish the narrative had the crazy courage of the image-making — Fake’s beautiful block-print lettering, say, or the dark navy-blue-colored series of double splashes that conclude the book, or the way he can fill a page with tiny accumulated circles and waves that buffet and subsume, or the lovely tangerine halftone and clean rounded lines that comprise the phoenix’s final mystical encounter. But the key here all along has been to let the artistic growth on display speak for itself, to do the heavy lifting of the story itself. Actions speak louder than words.

Comics Time: Two Eyes of the Beautiful Part II

May 20, 2011Two Eyes of the Beautiful Part II

Ryan Cecil Smith, writer/artist

self-published, 2010

48 pages

$5

Buy it from Ryan Cecil Smith

Like the previous chapter, this installment in Closed Caption Comics member Ryan Cecil Smith’s adaptation of Kazuo Umezu’s horror manga Blood Baptism achieves something damn close to horror camp. It’s a celebration of the over-the-top nastiness and spectacle of horror manga: Not content to show the killer, a demented ex-actress out to repair her disfigurement by any means necessary, strangle a dog to death, Smith depicts the woman’s hapless daughter stumbling into a room full of dismembered animal corpses and getting buried in a pile of severed cat heads. Even the villain’s hair is larger than life, an enormous bun taller than Marge Simpson’s beehive. This is all the funnier for being drawn in an altcomix-meets-kids’-manga style; it could just as easily be an uglied-up Sailor Moon tribute comic some kid from CCS did. But it’s precisely this idiosyncracy — a member of one of the States’ premiere underground comics collectives doing a respectfully ridiculous cover version of a horror manga about a crazy woman preparing to rip her own daughter’s brain out to achieve eternal youth — that elevates it from cheap irony or schlock. From the expert zipatone shading to an immaculately inked centerfold spread of that room full of dead dogs (it’s all painstakingly delineated grains in the hardwood floor and shiny black puddles of blood), Smith is pouring a very serious amount of effort and craft into what could easily have been just a goof, because to him, it clearly isn’t. Most impressive to me is the way he depicts his little-girl protagonist’s reaction to her discovery of her mother’s true nature. As she panics and tries to escape, Smith crops her word balloons so they cut off the text of her speech so that only half the letters (top, bottom, left, right, whatever) are visible, the rest of each alphabetical character disappearing under the edge of the balloon or panel. Panel borders and balloon edges, the very containers from which comics are comprised, are inadequate to contain the overwhelming horror she feels. That’s a lot of smarts to bring to an arch horror-comedy experiment. It kicks the shit out of Black Swan, that’s for sure.

Comics Time: Lose #3

May 18, 2011 Lose #3

Lose #3

Michael DeForge, writer/artist

Koyama Press, May 2011

pages

$5

Buy it from Michael DeForge

It’s one thing to take a Chris Ware/Daniel Clowes middle-aged sad-sack comedy of discomfort and plop it into a slime-encrusted anthropomorphized-mutant-animal-inhabited post-apocalyptic hellscape that looks like Jon Vermilyea staging a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles revival in the middle of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. It’s quite another thing to do this well. And it’s still another thing to do it so well that while the whole is indeed more than the sum of its parts, the parts work all on their own, too. That’s the achievement of Lose #3, the latest installment in Michael DeForge’s old-school one-man alternative comic series.

In past issues, as well as in his minis and anthology contributions, DeForge has proven adept at crafting razor-sharp embodiments/lampoons of what have been termed “first world problems” and placing them in the mouths of fantastical, outlandishly designed and drawn creatures and monsters and superheroes and giant mecha and what have you. (“I feel like things have been weird between us lately,” reads the image of the shaggy faceless beast rolling around on the ground — that sort of thing.) And he does that here, too, to cringingly devastating effect: The text for the opening one-pager is a letter from a fresh-faced intern high on his first trip to NYC to his mother back home (“I asked if there were any paid positions opening at the magazine in the fall. They said things were still up in the air for now. Fingers crossed, I suppose!”), juxtaposed against the images of a naked man riding a spotted deer through a debris-strewn wasteland in order to pour the coffee he purchases at a still-standing chain coffee house into the maw of the creature that lives in his cave. Toward the end of the collection, ants wax pessimistic about life in these weird, dark times (“But, like — why do we live this way? It’s — it’s nuts that this is the ‘norm’ for us,” says an ant about the potential for human beings to burn them with magnifying glasses) and debate whether or not to move the dead body of a friend when its pheromones start attracting a crowd (“Just leave it. It’s a party”) Even in the main story, there’s a bit where the two teenage sons of our divorced protagonist talk about The Wire that nails the clichés of that particular conversation so accurately even without mentioning it by name (“The show introduces a new part of the city at the beginning of each season, so it’s always, like, BOOM! Bigger picture! BOOM! Bigger picture! You know?”) that I wanted to delete my old blog entries about the show.

The innovation of “Dog 2070,” Lose #3’s centerpiece story, is, well, that it’s a story, a look at a very shitty month in the life of a middle-aged flying-dog-man-thing. He concern-trolls his ex-wife over her current husband, his attempts to connect with his teenage and twentysomething kids are rebuffed with casual cruelty, he fixates on his own problems to the pint where he can’t empathize with cancer patients, his neurosis leaves him equally unable to spend his time at the computer productively writing or unproductively masturbating, he drunkenly confronts his middle-school son’s ex-girlfriend after a cyberbullying website the kid made about her nearly gets him expelled from school, he ends up in the hospital after a freak gliding accident. It’s easy to focus on the yuks here, which are abundant in the same way they are in Wilson or Lint — the sudden reveal of our hero Stephen’s inebriation when talking to his kid’s ex is impeccably timed to elicit an “Oh, Jesus” guffaw, and DeForge nearly always chooses dead-on details to illustrate the guy’s creepy self-absorption, from giving his ex-in-laws gifts on Thanksgiving just to stay in their lives to interrupting a conversation about a co-workers chemo to announce he’s begun therapy as research for his screenplay. (The flying scene, in which a soaring Stephen sums it all up by saying “Sometimes it’s as if I forget we’re able to glide!,” then crashes into a bird, is a bit on the nose, though.) But DeForge reveals the true emotional stakes in a pair of dream sequences as recounted by Stephen to his therapist. In the first, we watch the flesh slowly slough off his daughter, who recently attempted suicide, before she fades away from view; in the second, he and his former family, reduced to four-legged animalistic versions of their anthropomorphized selves, fight over a scrap of meat. “I just feel so ashamed I don’t know why. I’m watching it and I just feel awful.” This, of all the notes he hits, is the one he chooses to leave us with, a nightmare representation of a failing man’s worst fears and shames, to which he has no adequate response and to which no adequate response is provided. That’s when you realize that these emotional stakes have been present all along, hiding in plain sight: In the omnipresent beads of sweat oozing down Stephen’s fleshy body, in the debris-strewn streets and burned-out buildings that form a backdrop for the story, in the walls that seem to sweat and drip and bleed themselves. Something is wrong, the art says, even as the narrative chronicles the banal travails of a relatively normal guy. DeForge doesn’t need to come right out and say it himself. Lose #3 isn’t the bolt-from-the-blue paradigm-shifter I’ve seen some people describe it as, but it’s a confident enough comic that it doesn’t need to be, pushing its author out of his comfort zone only to discover he’s perfectly comfortable here, too.

Comics Time: Garden

May 16, 2011 Garden

Garden

Yuichi Yokoyama, writer/artist

PictureBox, May 2011

320 pages

$24.95

Buy it from PictureBox

Buy it from Amazon.com

Meet the non-narrative pageturner. Garden is Yuichi Yokoyama’s third English-language release from PictureBox, and his most viscerally thrilling work to date. It’s the clearest demonstration yet of the innovation that is his masterstroke: fusing visually and thematically abstract material with the breakneck forward momentum, eye-popping spectacle, and pulse-pounding sense of stakes of the rawest plot-driven action storytelling.

Garden has no story to tell, of course, not as such: It simply depicts a large group of sightseers who break into a vast manmade “garden” of enormous natural features combined with artificial and mechanical objects, wander around, and describe and inquire after what they see. With their matter-of-fact pronouncements (“There are many ponds. This one is jagged. There is a giant ball floating in this one. This one is made of stainless steel. We have now arrived at a significantly larger pond.”) doing the heavy lifting of parsing exactly what we’re looking at for us, we’re freed to simply go along for the ride, marveling at each new environment Yokoyama dreams up. As a feat of sheer bizarre imagination it’s tough to top: I can easily picture standing around with other readers comparing favorites — “I liked the hall of bubbles!” “I liked the stack of boats!” “I liked the river of balls!” “I liked the giant book!” “I liked the polaroid carpet-bombing!” “I liked the monkey bars!” Imagine if everything in Walt Disney World were as alien and strange as the giant golfball Spaceship Earth and you’re almost there. Nearly every new area and attraction practically demands to be stolen and used for a setpiece in someone’s weird alt-SFF webcomic. And with a “narrative” through-line that’s 100% pure exploration — lots of little guys walking and climbing and sliding and crawling through doorways and scaling mountains made of glass and so on — echoes of their tactile, discovery-driven adventure can’t help but hit us and excite us as we race along with them to their eventual destination.

In essence, Garden teaches you how to read it. It immerses you in its perambulations and presents you with a new amazing thing with each turn of the page, engrossing you to the point where you hardly even notice that it’s a book-length exploration on Yokoyama’s part of geometric shapes, of the clean line, of costume design (all the little people wear headgear and outfits that make them look like a cross between Jason Voorhees and Carmen Miranda), of his own fascination with the way the natural world and the manmade world shape one another. I felt at the end of the book like I do at the end of a great theme-park vacation: Exhausted, invigorated, and already planning my return.

Comics Time: Paying For It

April 5, 2011Paying For It

Chester Brown, writer/artist

Drawn & Quarterly, April 2011

292 pages, hardcover

$24.95

Buy it from D&Q

Buy it from Amazon.com

My publishers wanted this book to be called PAYING FOR IT. I don’t like the title — there’s an implied double-meaning. It suggests that not only am I paying for sex but I’m also paying for being a john in some non-monetary way. Many would think that there’s an emotional cost — that johns are sad and lonely. There’s a potential health cost if one contracts a sexually transmitted disease. There’s a legal cost if one is arrested. If one is “outed,” then one could lose one’s job and also suffer the social cost of losing one’s friends and family. I haven’t been “paying for it” in any of those ways. I’m very far from being sad or lonely, I haven’t caught an S-T-D, I haven’t been arrested, I haven’t lost my c areer, and my friends and family haven’t rejected me (although I should admit that I still haven’t told my step-mom.

So far, I’ve been paying in only the one sense. (Since this is a memoir, “so far” is all that’s relevant.)

But let me be clear that my publishers did not force the title on me. I chose to give in to what they wanted. If I had insisted, they would have allowed me to put whatever words I wanted on the cover. I love and respect Chris and Peggy and realize that this is a difficult book to market.

–Chester Brown, in the entry pertaining to the Cover in the “Notes” section of Paying For It

“Difficult book to market”? Get outta town, Chet! When a review copy arrived at my house unexpectedly this Saturday, I tweeted, and quite seriously meant it when I did so, that having an infant in the neonatal intensive care unit was literally the only thing stopping me from dropping everything and reading this book right then and there. A parametric memoir from Chester Brown, the parameters of which were one of the great North American cartoonist’s experiences with prostitution? Appointment reading! Maybe it’s tough to market to the great unwashed, but you’d have to pry this thing out of my hands to keep me away.

As it turns out, Brown is right about the title his publishers selected. With its punning double meaning and slightly censorious elision of what, exactly, is being paid for, it’s all wrong for this straightfaced, blunt, even didactic sexual autobiography/soapbox lecture. “Paying for Sex” would be far more appropriate. Drop the cap from the “For” to make the phrase less idiomatic, insert the actual act back into the proceedings, and be as matter-of-fact and up-front as possible about what’s going on — which quality, not at all coincidentally, is a big part of why prostitution appeals so much to Brown in the first place. The social cues he seems unable to pick up on, the rituals he is congenitally incapable of performing, the years and decades of accrued guilt and sense of failure he built up from missing out on potential romantic or sexual relationships, the elaborate and to-him draining emotional quid pro quo of sex within the context of the few relationships he was able to enter into and maintain (that’s the context in which he really “paid for it”)…all of that disappeared the moment he told his first whore “Uh, I’d…like to have vaginal intercourse with you.” (“Yes, that’s what I really said,” he assures us helpfully in the “Notes” section.) It seems a shame to add a level of kabuki to the title of a book so fixated on taking it away.

This is not to say that humor has no place in the book. On the contrary, this thing is fucking hilarious. Much of this stems directly from how Brown draws what he draws. His Harold Gray tribute from Louis Riel has been abandoned (with the exception of Brown’s brother Gordon, who’s drawn like a Riel refugee). In its place are rigorous, unyielding two-column eight-panel grids filled with tiny, tiny people drawn in as smooth a line as you’re likely to see anywhere; “painstaking” is the word that comes to mind. Foremost among these tiny people is Brown himself; his self-caricature is gaunt to the point of skeletal, an impression enhanced by the pupil-hiding blank voids of his everpresent eyeglasses. (One of the “Notes” reveals that by a certain point in the narrative he’d begun wearing contact lenses, particularly when patronizing prostitutes, but he didn’t want to confuse the issue.) Seeing his eyeless face in three-quarter profile over and over and over and over and over again, page after page after page, is bizarrely hysterical after a while. It is the least sexy self-portrait possible — not just unsexy, but almost devoid of the energy one would think would be required to have sex at all. In the many scenes where Brown is accompanied by his best friends and fellow cartoonists Seth and Joe Matt, the portraiture gets funnier still. Watching the three bespectacled men — Brown balding and sullen, Matt babyfaced and effusive, Seth impossibly dapper and never without his suit, fedora, and cigarette — walk in lockstep down the city streets like some sort of morose urban Three Amigos is one of the unexpected comedic highlights of my comic-book year so far.

I know, I know: What about the fucking? Pretty funny too. Throughout the book Brown uses a sort of dilation effect to center one’s attention in each panel, tending to shade in the periphery of the panels with a circle of black, like an old silent movie. This is barely even noticeable until you hit the sex scenes, which tend to show a bareassed Brown silently thrusting away at the crotches of the whores in question, usually with several different physical configurations per encounter (which is to say per chapter, since each experience with a prostitute gets its own chapter). Before long Brown’s mid-coitus interior monologue features him calmly assessing the pros and cons of each prostitute — he thinks about how she stacks up against previous women he’s been with, whether or not to patronize them again, what kind of review he’ll give them on a website for clients of Toronto escorts, and so on. It’s so deadpan he might as well be in the produce aisle squeezing melons.

Which is the point. In the lengthy, handwritten prose section that ends the book — first a series of polemical Appendices detailing Brown’s exact position on the decriminalization (not legalization! keep the government out of it!) of prostitution and his responses to arguments against the profession, then a response from Seth to his depiction as a character in the book (“The truth is, Chester seems to have a very limited emotional range compared to most people. There does seem to be something wrong with him.”), then another series of Notes on various points of interest in the book — Brown advances an admittedly quixotic vision of a world where paying for sex is an utter commonplace, a practice so pervasive that the need for professional prostitutes is lessened because you or I would have no problem exchanging money for sex with our attractive friends and acquaintances and vice versa, the same way we might go to movies together or send a friendly email. The important thing to Brown isn’t just decriminalizing the supposed offense of giving or receiving money for sex, it’s deflating the romanticized aura of the act itself.

As you’ll learn at great length from Brown, both in monlogues within the comic and in the prose material appended to it, the book isn’t so much about prostitution in and of itself as it is about the way Brown has rejiggered his life in order to avoid the “evil” of romantic love, or “possessive monogamy” as he comes to exclusively put it. Unlike familial or friendship love, romantic love in its idealized form is exclusive — you love one person, that one person loves you, and neither of you is allowed to feel the feelings you have for one another or have the sex you have with one another with anyone else. This leads to jealousy, an emotion Brown views as immature and immensely destructive. The solution? Separate sex from its romantic context entirely. Have close friends and companions from whom you get all the benefits of friendship love, which is superior to romantic love anyway, and then have sex with people of whom your contractual obligation to whom ensures that you will have no further expectations, nor they of you. Sex is sacred, Brown argues — so it should be made available without stigma or shame to as many people as possible. What better way to accomplish this than cash?

So that’s the platform here. Brown wants to do away with romantic love, and prostitution has enabled him to do this.

Except for one jaw-dropping revelation he sneaks into the final eight pages’ worth of comics: UPDATE: Actual revelation redacted, but suffice it to say it calls into question, if not outright undermines, all the Big Ideas he’s been advancing all along. This is the key to the whole fucking thing, and he shoves it away in a single chapter! If this is the way life is to be lived in Brown World, then don’t we need to see how it’s lived if the entire project is to have any value? That’s where the rubber hits the road! So to speak!

And once you realize that Brown has pulled the knockout punch, so many other things you’d been willing to overlook due to his overall breathtaking candor and craft become harder to excuse. Every prostitute we meet, for example, is depicted as a faceless brunette. Now, it’s abundantly clear why he wouldn’t want to actually draw these women true to life even without his notes explaining this decision, but noting that he did in fact see prostitutes who weren’t pale brunettes doesn’t change the fact that that’s how he drew all of them — nor does it make the fact that he drew their naked bodies as accurately as possible but left them a faceless raven-haired horde otherwise any less unwittingly (?) revealing.

Then there’s the chapter where he has sex with a very young-looking, foreign-born prostitute who gasps in pain throughout intercourse: “That she seems to be in pain is kind of a turn-on for me, but I also feel bad for her. I’m gonna cut this short and cum quickly.” What a gentleman! In the Notes he reveals he was astonishingly naive — credulity-stretchingly so, to be honest, for someone who appears to be so well-educated in every other aspect of the literature of prostitution — about the existence of sex slaves, whom he continuously talks about as though kidnapping by force were the preferred method of harvesting them, as opposed to false-pretense illegal-immigrant indentured-servitude. “Was ‘Arlene’ a sex slave? She didn’t seem like one,” he shrugs in the Notes about this painful encounter, before quoting someone on how “outcall” prostitutes (those who come to your apartment) are unlikely to be sex slaves since they could always go for help instead. Anyone who’s watched a single episode of Law & Order: SVU or Dateline NBC could shoot this whole element of things so full of holes you could use it as a colander.

The thing is, like Brown, I don’t think the existence of sex slaves necessitates the continued illegality of prostitution, any more than the existence of labor slaves meant we should ban the harvesting of cotton or the performance of housework. He’s quite right to say that were prostitution decriminalized, law enforcement could focus on forced prostitution that much more readily. It’s the “forced” that matters, not the “prostitution.” But for a guy who’s so willing to extrapolate universal principles from his personal experiences — his mother’s disastrous, effectively lethal course of treatment for schizophrenia means schizophrenia doesn’t exist; his unhappy experiences with romantic relationships mean that romantic relationships are a categorical evil — he sure doesn’t mind leaping right the fuck past any personal experience, or those of anyone else, that might cause those principles harm. And, you know, hey, that’s how almost all of us live, to one extent or another (most of us not to the extent that we need to wonder whether or not a given sex partner is a sex slave, but to some extent at least). That’s human, and we forgive each other for it in life. In art? Art explicitly dedicated to the advancement of some philosophical and political truth? Then that’s the sort of thing you gotta pay for.

Comics Time: R.I.P.: Best of 1985-2004

March 24, 2011R.I.P.: Best of 1985-2004

Thomas Ott, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, March 2011

192 pages, hardcover

$28.99

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

For today’s Comics Time review, please visit The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: The Cardboard Valise

March 7, 2011The Cardboard Valise

Ben Katchor, writer/artist

Pantheon, March 2011

128 pages, hardcover

$25.95

Buy it for damn near 50% off right now at Amazon.com

Comics Time: Angel

February 23, 2011Angel

L. Nichols, writer/artist

self-published on the web, September 2009-August 2010

129 pages

Read it at DirtBetweenMyToes.com

I worry that I over rely on comparing comics to still other comics when reviewing them, but once this comparison occurred to me there was no way I wasn’t gonna use it: L. Nichols’ Angel is like Benjamin Marra’s Night Business crossed with Megan Kelso’s Artichoke Tales. Like the former, it’s a straight-faced homage to the trash aesthetic of late-’70s/early-’80s black-and-white genre comics and grindhouse/straight-to-video movies — this time it’s not erotic urban slasher thrillers being saluted, but post-apocalyptic gang-warfare stories. And like the latter, it’s using a somewhat disreputable genre as a filter for a story about violent conflict’s disruptive effects on friendships, love, and sex — Angel‘s funneling of queer sexuality through an idiosyncratically Brooklynite (lots of bike-riders!) Warriors-scape replaces Kelso’s multi-generational saga of lovers tossed around an epic anthropomorphized-artichoke fantasy framework by the winds of war

To be sure, it’s not quite as accomplished as either of those works. In a way, the seriousness of the emotional stuff Nichols is working with undercuts one of the great strengths of Marra’s comparable comics, which is how hard he can make you laugh at the sheer go-for-the-gusto-ness of it all. Where Marra’s sex and violence is garish, gaudy, and over-the-top, Nichols’s is a bit subdued and somber, and ironically that makes the pulpy prose (see page one above) harder to swallow. At the same time, though, the romantic entanglements, however far afield they roam in terms of the gender and sexuality of the participants, are much more firmly in the straightforwardly star-crossed lovers mold of traditional genre comics and movies than Kelso’s richly imagined couples and families. Moreover, the action sequences tend to be pretty much one beat per panel, making it difficult to get a sense of where characters are in relation to one another or what the consequences of any given shot or swing or explosion really are. The climactic battle sequence builds up an impressive momentum with its page after page of isolated action incidents, but in smaller doses, this method of pacing can be frustrating.

But that pacing is hers. That’s the important thing here, I think. And that melancholy combination of over-the-top ’80s-action cheese and bodice-ripping (or strap-on-wielding) romantic intensity is hers. Like the best alt-genre/”new action”/fusion comics, Angel isn’t an artist molding her ideas into a preexisting template, it’s her using her ideas as the template, and pouring bits and pieces of the genre art she loves into the mix to fill it up. When it works, it’s really exciting: Those staccato panels, which hardly ever show two people in the same frame and frequently don’t even show entire faces, create a real sense of paranoia and insecurity in that post-apocalyptic landscape. And the romantic material is affectingly personal despite its clichés. It’s not an action comic with heart, it’s a heart comic with an action, if that makes any sense. It’s not intended to be rad or stylish or awesome or sexy or cool or now, it’s intended to be exactly the combination of personal preoccupations and obsessions that it is. If I could say that about all alt-genre comics, whatever their other flaws, I could read them all damn day and still feel like I wasn’t cheating myself of the unfettered personal expression the best of the “alt” side of that equation can offer.

Comics Time: “His Face All Red”

February 21, 2011“His Face All Red”

Emily Carroll, writer/artist

self-published on the web, October 2010

Read it at EmCarroll.com

I’ve said a lot of complimentary things about this comic in the months since it was first posted, but it occurred to me I never actually sat down and reviewed it. So the other night I loaded it up for re-reading with the express purpose of writing a review in mind. And despite having looked at it however many times since it went up on Halloween, I still found myself dreading, literally dreading, the final image. Familiarity bred fear. From the striking title to the matter-of-fact opening line to the final page turn, Emily Carroll’s “His Face All Red” is an engrossing, quietly terrifying horror comic. You could be forgiven for thinking it might not be, by the way. Carroll’s slick-sexy-cute illustration style is very popular on the Internet, the kind of stuff that gets endlessly reblogged and Tumblrd and LJd; it’s easy to picture her earning plaudits for doing realistically cute redesigns of Supergirl’s costume, or a killer suite of Scott Pilgrim or Harry Potter portraits, or a drawing of Mal Reynolds and The Tenth Doctor reenacting Alfred Eisenstaedt’s “V-J Day in Times Square,” or whatever. So yeah, I could stand to see it de-prettified in the future. But here she applies that readily appealing craft in ways above and beyond what she could have easily gotten away with doing. Her use of the web to control pacing is really masterful: She uses the long vertical scroll to create an almost hypnotic feeling of inevitable descent as we watch our narrator explain why and how he killed his brother, and try to figure out why and how someone who looks and acts just like him appeared the next day, acting like nothing had happened; she then breaks this flow in jarring fashion with a pair of pages that contain but a single indelible image, one after the other. All this against a pitch-black background, further enhancing the immersiveness of the story. And that final turn of the page! Really pitch-perfect cartooning and pitch-perfect horror pacing, showing us just enough to let us know that something truly terrible is before us. I don’t want to spoil anything, but I found that in the weeks since I last saw it, my mind had added details to the image — they weren’t really present there, but the tone of utter shattering of reality’s norms conjured them nonetheless. Enormously effective and affecting work, as close to delivering a jump-scare as any comic I’ve read. Shudder.

Comics Time: “2001”

February 18, 2011“2001”

Blaise Larmee, writer/artist

self-published on the web, January 2011-

Read it at BlaiseLarmee.com

What a thrilling comic. It’s worth noting, I suppose, that the white-on-black presentation of Blaise Larmee’s gorgeous webcomic “2001” largely removes Larmee’s work from the pencil-smudged, fragile-lines-on-white, Darger/CF context in which it’s previously been located. But far more interesting to me than how the comic operates versus Larmee’s other stuff is how it operates in and of itself. The vastness of the full-bleed images, the fact that they occupy the entire page, the way the starfield/snowfall background is a big black nothing that appears to isolate the characters in infinity, is immediately impactful, even awe-inspiring, maybe the most striking use of the webcomic medium I’ve ever seen. Now that enough pages have accrued, however, we discover that Larmee isn’t just tracking bodies in space, but bodies in a particular space. The big geometric planes of white and black that interrupt the snow/stars, we can now tell, are a building or structure of some sort — the white its roof, the black its walls — around which our two heroines twirl and leap and walk and peek. Storywise, there’s not much more to it at the moment, beyond some almost Bendisesque cute dialogue about how “very May ’68” the place is and how they’ve got tea but want coffee instead. But there needn’t be more to it than what there is: An innovative, arresting, and beautiful way to arrange movement on a comics page, and to arrange a comics page, period.