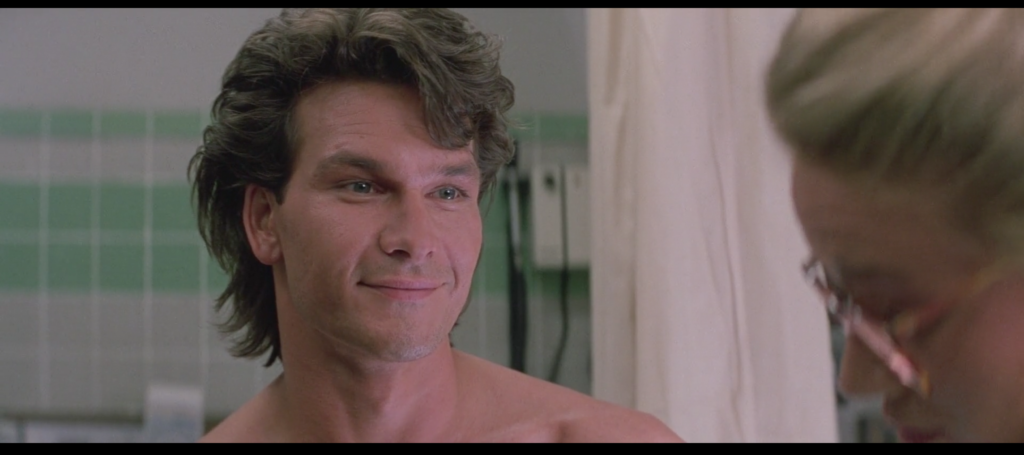

“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

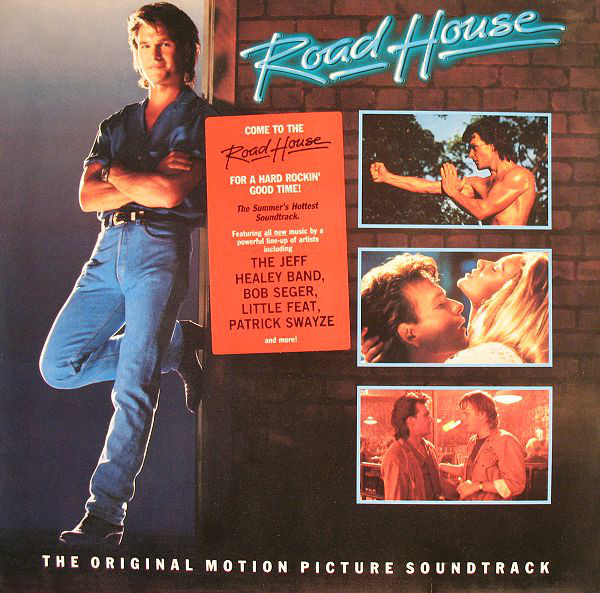

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, for the final time, is the third.

3. Be nice (concluded)

Previously:

- The Great Commandment

- The Parable of Someone Getting in Your Face and Calling You a Cocksucker

- Walking the Dalton Path Together

- It’s a Job / It’s Nothing Personal

- Two Nouns Combined to Elicit a Prescribed Response

As our lessons have shown us, there is nothing simple about the simplest of the Three Simple Rules. Be nice: Those two words pack a world of meaning into their duosyllabic totality. Through parable and paradox and painstaking explication of every detail, Dalton slowly indoctrinates his disciples in the six letters (plus a space) that are the true determinant of the Dalton Path’s meandering course.

Naturally, the Dalton Path must include its own Path-annihilating destination.

3 (Revised). Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.

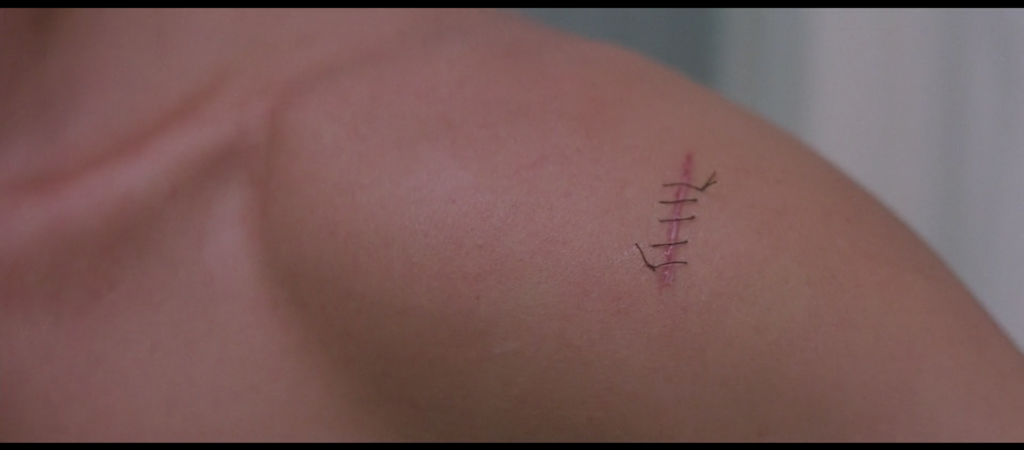

That’s what Dalton wants. He says so. “I want you to be nice…until it’s time to not be nice,” he says, in so many words. This is the second time he’s given voice to his own desires when delineating the Third Rule, the other being “I want you to remember that it’s a job—it’s nothing personal.” We can hereby conclude first that nature of the work as work, as labor, is of central importance. Indeed we will see how this conception of the job allows Dalton both to assert that, as a laborer, he is entitled to all he creates, and how it gives him the detachment necessary to see himself (his self) as separate from the job that his self performs.

But it’s the second half that clues us in here. We recall that in saying “It’s nothing personal,” Dalton was employing the old “If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig” technique: He waltzed into these people’s place of business, fired several of them, told them his authority is absolute, noted what a bad job they’ve been doing, personally insulted them—sometimes via parable, sometimes via insinuation, always indirectly so as to stymie their righteousness in lashing back. If they managed not to take what he was doing personally, then they already will have understood the importance of not taking things personally.

Which brings us back to “Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.”

“Well, uh, how are we supposed to know when that is?” asks Younger, the quietest of Dalton’s new believers.

“You won’t,” Dalton says. “I’ll let you know. You are the bouncers. I am the cooler. All I want you to do is watch my back—and each other’s…Take out the trash.”

We already know that the Dalton Path is a path we walk together. Here, at the end of the path, the point at which the Third Rule gives way to its opposite, where thesis becomes antithesis, where being nice becomes not being nice, is where we receive the most emphatic declaration of our collectivity.

It is not for us to know when the time to not be nice has come. We are but bouncers, seeing through a pint glass darkly. Dalton, the Cooler, will instruct us. And yet the cooler cannot be the cooler without his bouncers. He needs us to watch his back—and each other’s—just as much as we need him to tell us the day and the hour of the not-niceness.

This is all part of the same thought-flow, each point indistinguishable from the last. Without bouncers, the cooler cannot cool; without the cooler, the bouncers cannot bounce. Ad infinitum, world without end, amen.

And what are the Three Simple Rules, if not the cooler distilled to his intellectual essence, the flesh made Word? Time and time again we have seen how when released into a mind willing to receive them, they act independently, engendering the understanding required to understand them as they take their course. Each rule is Dalton made miniature, released into the Double Deuce of the mind, taking out the trash. And within ourselves, we have watched his back all along.

We will not know when the time has come to not be nice. We won’t need to. Dalton will tell us. He already has.

This marks the midpoint of Pain Don’t Hurt. Thank you for reading.