I sometimes think of Road House as a sublime movie, and that’s not an adjective I throw around for movies that often. For me it’s reserved for films that transport me into a place of tangible, physical awe—the equivalent of musical frisson, that chill you get up and down your spine and through your skull from art that stuns you. If you know me at all it won’t surprise you to learn that I get this feeling most often from horror films. I think Jaws is sublime. I think The Exorcist is sublime. I think The Shining is sublime. I think Aliens is sublime. I think Hereditary is sublime. I think Barton Fink is sublime. You get the idea. So you get that Road House does not transport me the way any of those movies do.

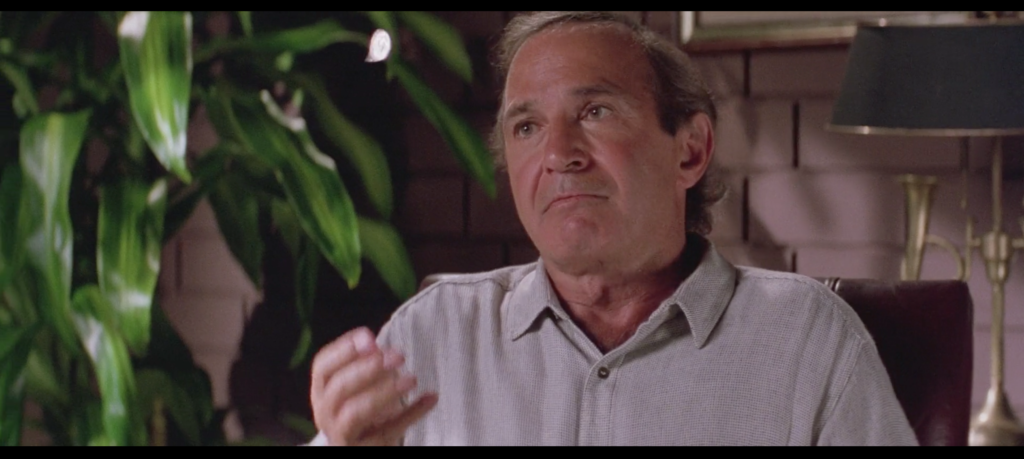

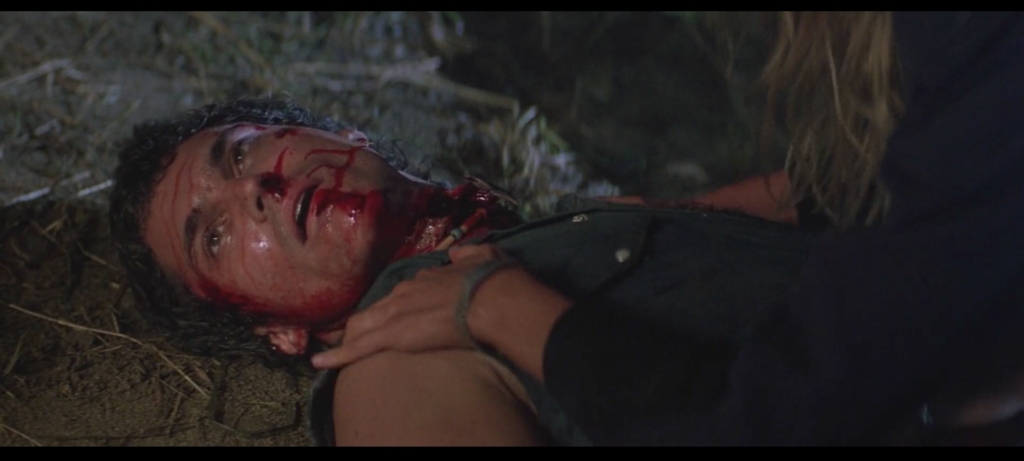

Why is Road House sublime? Because sandwiched in between two identical parking scenes and a scene in which two lovers confront one another over matters of life and death in front of a bunch of x-rays of people’s colons, Patrick Swayze looks at Sam Elliot like he does above and below. First: total love, respect, humility—he is admitting he was wrong after all—and above all gratitude that he gets to know this man. Then: total loss, grief, anger, denial, anything but acceptance that this man who meant so much to him is gone.

The word I use to describe Patrick Swayze as an actor is generous. He gave himself over to this absurd role in this absurd film, used every ounce of his training as an actor and a professional-grade stuntman and a professional-grade ballet dancer. Every interview I’ve ever seen with Kelly Lynch or Marshall Teague or Sam Elliott in which they’re asked about this film is full of superlatives of how dedicated he was, and how kind he was, and how the experience of working with him was…well, they don’t say it, but I will: sublime.

Parking, acting, colons, parking, more acting, acting like his life has fallen apart, like the person he loves most in the world has been stolen from him. His eyes squint with tears and she shakes his head wildly back and forth, moving his whole upper body at one point, his whole self one gigantic No. Some of the dumbest filmmaking I’ve ever seen, and then this. Sublime.