I love writing about action filmmaking and cartooning, even if action is not my favorite genre in either art form. (Though I do like it a lot. Perhaps you’ve heard about my affection for a film called Road House?) Years ago now, one of my friends and colleagues at a comics-industry magazine I worked for said I was three critics in one: the horror guy, the fight scene guy, and the pervert. He was not wrong!

A sense of place, a sense of space, is what I look for above virtually anything else in an action scene. I want the fight to be rooted in its environment, making use of its unique advantages and obstacles. I want to be able to parse the spatial relationships between the combatants at all times, so I understand who is at risk and when and why. I want each movement to have tangible physical stakes and consequences I can parse against the spacial and environmental backdrop. From the “Duel of the Fates” sequence in The Phantom Menace to the alleyway slugfest in They Live to the beach fight right here in Road House, great fight scenes deliver in these criteria.

So I want to be clear about this: The beginning of Dalton and Wesley’s final battle makes no sense at all.

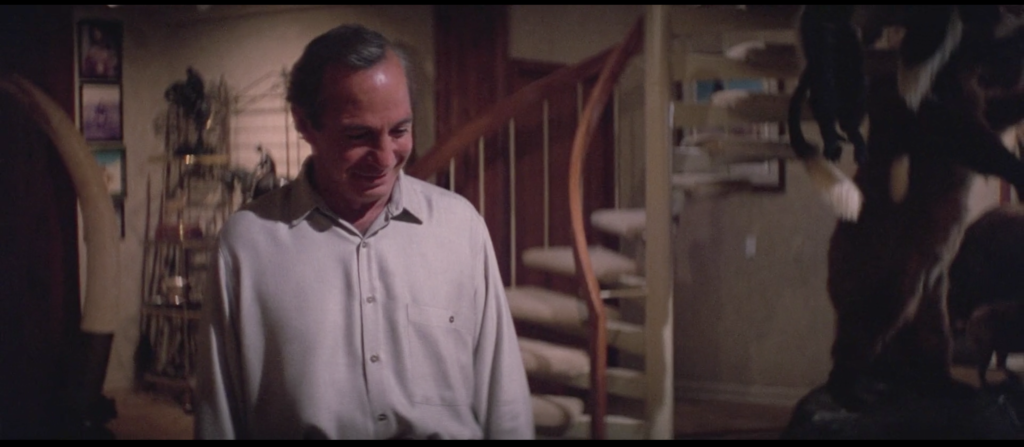

Wesley is walking through his trophy room, starting from base of the staircase. A POV shot reveals his surroundings: To his right is a living-room set, and to his left is a wall with a stuffed bear, a stuffed hyena, and a stuffed buffalo. There is a good deal of space between these animals. Behind them is a blank white wall.

Rather intelligently, considering that it’s the first place along Wesley’s route where Dalton could conceivably find cover, Wesley whips to his left and points his gun toward the wall immediately after passing the buffalo. There’s even a little sting from Michael Kamen’s score to dramatize the moment.

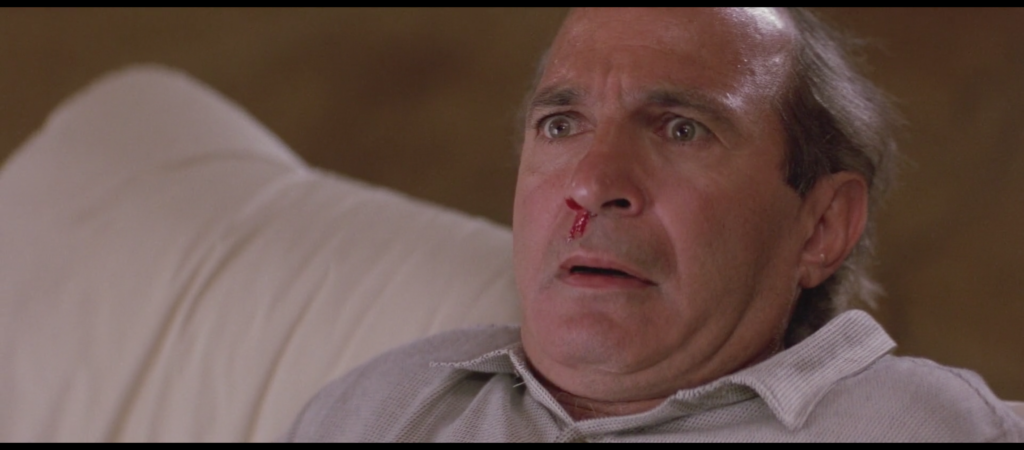

Unfortunately, Dalton is not there. Dalton is in fact behind the buffalo, as we can see when he slowly emerges after Wesley lets down his guard. Dalton kicks, Wesley shoots and grazes Dalton’s arm, and the game is afoot.

Do you see the problem here? Dalton was hiding in a place plainly visible throughout the course of Wesley’s patrol. Unless he quickly tiptoed from some unseen hidden recess behind that bear, taking care not to bump any of the animals or make any noise or emerge into the view of the gun-toting man about four feet away from him, it is literally impossible for Dalton to do what he does. Wesley would have seen him no matter what.

You know that part in Funny Games where the guy breaks the fourth wall and rewinds the action so that the outcome plays in his favor? Perhaps this is Road House anticipating that move years in advance. Perhaps the focused totality of Dalton’s bouncer powers enabled him to warp time and space around him so he could appear someplace he hadn’t been moments before, or rendered him invisible to Wesley’s eye until it came time to strike. Perhaps the invisible hand of Rowdy Herrington himself just plopped him there and let him loose so that the final battle could at last begin. Perhaps the three parking-lot scenes are designed to impress upon us the film’s almost ponderous understanding of physical space, so we don’t question it when it makes no sense at all.

Anyway, the psychotic JC Penney developer gets attacked by a bloodthirsty bouncer who was hiding behind his stuffed buffalo. And that’s all you need to know, son.