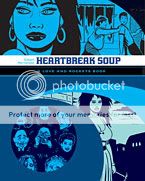

Heartbreak Soup

(Love and Rockets Library: Palomar, Book One)

Gilbert Hernandez, writer/artist

Fantagraphics, 2007

292 pages

$14.95

Buy it from Fantagraphics

Buy it from Amazon.com

(Programming Note: Due to technical difficulties, I was unable to post this review during the regularly scheduled Comics Time slot on Wednesday of this week. This is the first time I’ve missed a Comics Time deadline, scheduled time off aside, in probably two years, and I’m pretty bummed. My hope is to resume the regular MWF schedule beginning tomorrow, but delays or erratic scheduling may continue until the issue is resolved. I apologize for the interruption in service. Anyway…)

The great temptation when discussing Los Bros Hernandez, and it’s a temptation I’ve succumbed to, is to operate under the assumption that they’re both trying to do basically the same thing, only one of them is better than the other at it. Now, obviously, they are doing many of the same things. They’re brothers who co-founded a series they share in which they tell the sprawling saga of groups of (mostly) Latin American (mostly) young adults that unfold over (mostly) real time, dealing frankly with issues of sex, community, and mortality, starring women who are the closest alternative comics have come to generating sex symbols, and utilizing striking black and white art and inventive, challenging pacing. If that’s all you’re going by (and granted, it’s a lot!), then it’s almost irresistible to point to an element you feel one brother has over the other–Jaime’s incorporation of poster-ready design into his visual storytelling, say, or Gilbert’s magical-realist literary panache–and call him the victor.

But a) much as we comics folks love looking at absolutely everything otherwise, it’s really not a “who’d win in a fight” situation, and b) my re-read of Heartbreak Soup has me more convinced than other that the differences between Beto and Xaime are not differences of degree, but differences of kind.

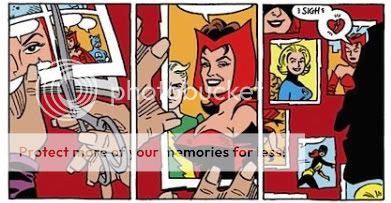

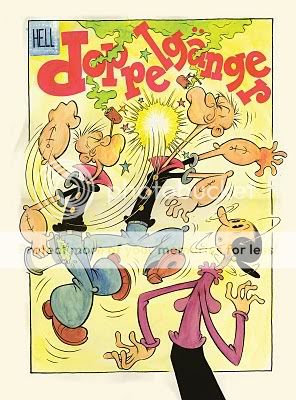

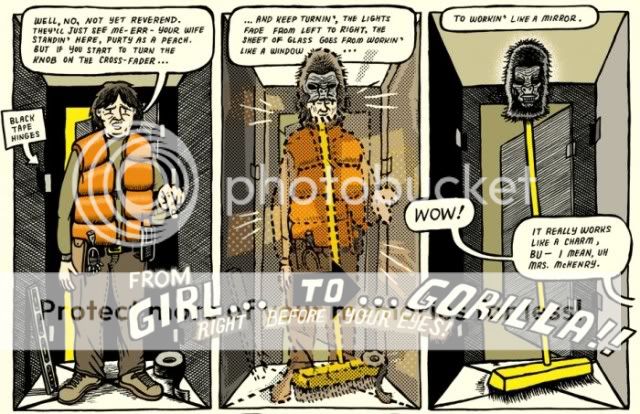

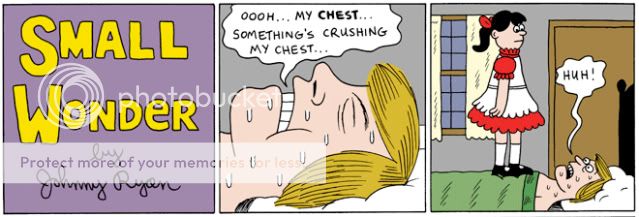

Let’s talk about the art first. This is the arena where Jaime is most frequently said to have it over Gilbert. And indeed, I can happily imagine a day spent doing nothing but looking at drawings of Terry Downe or Doyle Blackburn. That smooth line, those sumptuous, propulsive blacks, those enormously appealing and endearing character designs–it really is eye candy, in the best sense of that term. But a key goal of Jaime’s art, besides being pleasant to look at, is pop. Not in the sense of “pop art,” although I think that’s a major element and not just due to the occasional overt Lichtenstein homage, but in the sense that they pop off the page. Those blacks fill in space in a way designed to sharply foreground the figures and objects Jaime wants you to focus on or remember, something his sharp, slick line abets. When I picture Jaime panels, I tend to picture the characters are arrayed in a line from left to right against some sort of horizontally oriented background like a car or a wall, like actors (or punk rockers) on a stage. Moreover, he tends to draw his characters in poses and facial expressions that come across as, well, poses–the precise moment at which whatever they’re feeling or thinking or saying or doing is communicated most clearly, so that that thing pops off the page. The overall effect is that there’s them in the spotlight, and then there’s the other stuff against which that spotlight is defined.

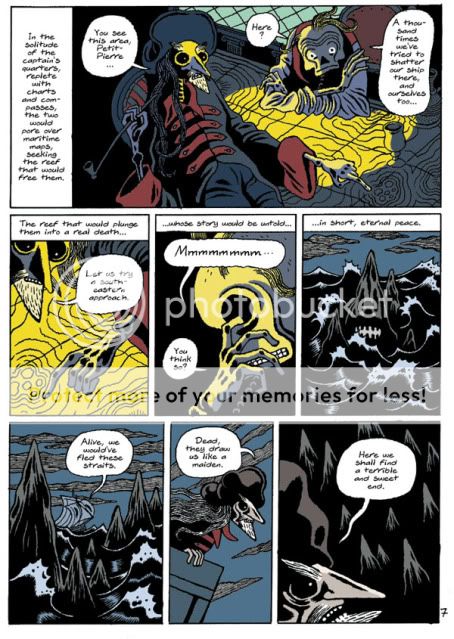

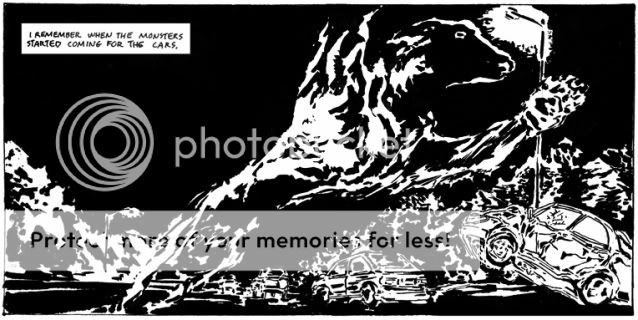

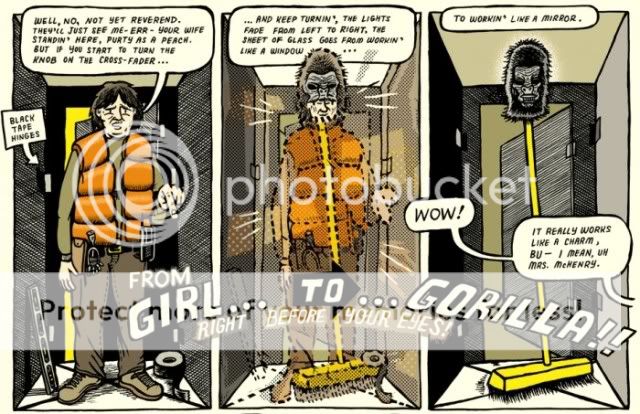

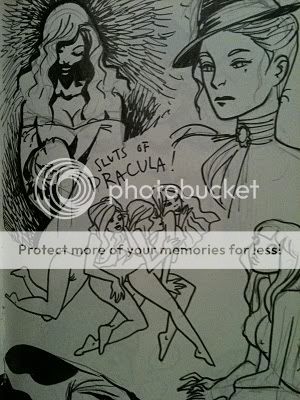

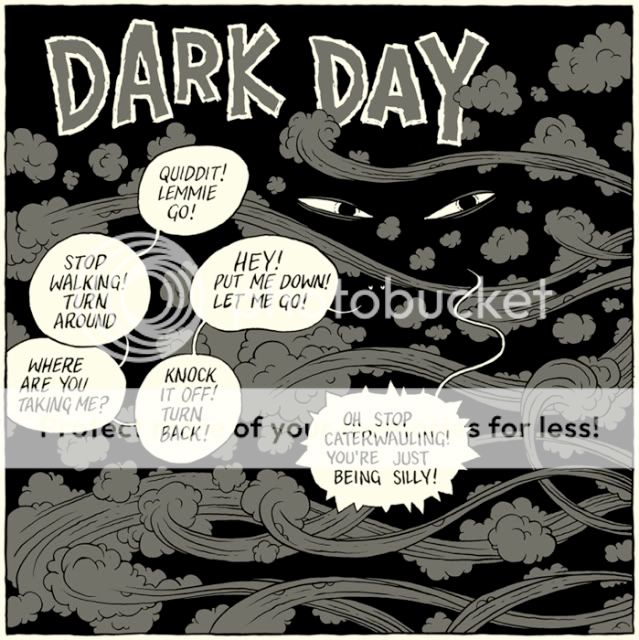

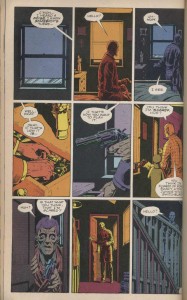

By contrast, when I picture Beto panels, I picture someone more or less standing around, usually with one or more other characters milling around as well, with the house-lined streets and intersections of Palomar extending out to the back left and back right. The very setting of his stories is one through which his characters are constantly walking to get from one place to another; I couldn’t draw you a map of Palomar or anything like that, but I feel like I’ve been walked through its streets much more than I can say that of Hoppers. Moreover there’s a casual element to Gilbert’s imagery that Jaime’s more compositionally calibrated panels don’t have. Beto’s line is rubbery, and complimented not by masterful fields of smooth, clean black but by shading and stippling that feels almost dusty. His character designs famously overemphasize flaws and virtues alike, and have a uniformly heavy-lidded weight to them; my wife simply describes his characters as “hard.” It’s tough to imagine spending a pleasant few hours staring even at Tonantzin or Israel the way you might at Maggie or Rand Race. And when characters are depicted for maximum impact, it feels like it’s being done through great force of effort on Gilbert’s part rather than with the effortless, effervescent precision with which Jaime does it. It’s also almost always either something the characters in question are doing on purpose to impress someone else, or a shot of them as seen by someone who they’ve impressed unwittingly. The overall effect feels calculated more for immersion than impact.

Then there are the stories and subject matter. One difference is obvious from the start: Jaime had a couple-issue jump on his brother in terms of beginning his magnum opus, but the delay gave Gilbert the opportunity to draw a bright line between his science-fiction work and his (occasionally magical) realist material. But beyond that, Gilbert very rapidly jumps his action forward about ten years or so from the first major story to the next, while Jaime’s almost resolutely marches forward in sync with our own real-world timeline. Jaime presents material from the past largely in the context of memory and how it intrudes upon and influences us; arguably the past’s on-again off-again love affair with the present is even more central to the Locas strips than Maggie and Hopey’s. Gilbert, however, doesn’t usually view stories from back in the day through that psychological lens. They tend to be presented as discreet tales, filling in backstory, spotlighting a character or a relationship, illuminating a part of Palomar we haven’t seen, depicting someone or something lost to time. Jaime’s interest in the past is primarily internal in its effect; Gilbert’s is primarily epic.

Particularly in light of their recent work, there’s another difference between Gilbert and Jaime worth pointing out. Jaime’s work is studded with sit-up-and-take-notice stories, and his most harrowing stuff–“The Death of Speedy Ortiz,” “Flies on the Ceiling,” and now “Browntown/The Love Bunglers”–tends to be among them. But when you hit “The Death of Speedy,” it’s not as though it establishes the tone for the rest of the series. It’s an exception, not a rule. “Locas” tends to be lighthearted even though what it’s really about–friendship, sexuality, identity, adulthood–is actually quite serious.

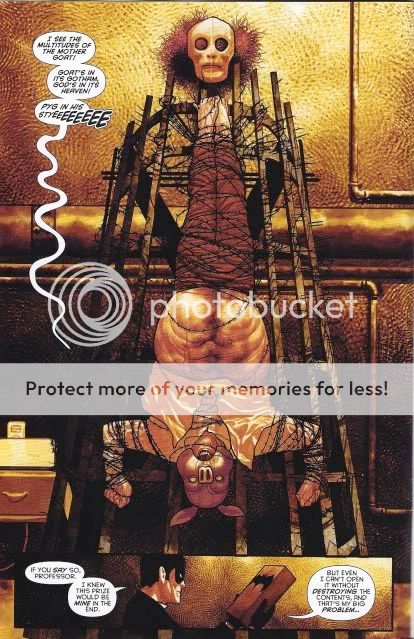

By contrast, the harshness, seediness, and bleakness of the world of Palomar and of Gilbert’s work generally–the love many of his characters feel for one another notwithstanding–tends to be what first comes to mind when I think of his comics. Yet Heatbreak Soup struck me for how good-natured it feels, up until the very end. Yes, sex is presented from the very first strip as a magnetic force with the potential for incalculable damage, and the book often does feel like “horniness punctuated by the occasional physical assault.” But centering the material on good-hearted Heraclio, unpredictable Luba, and packs of sweetly belligerent little kids and teenagers goes a long way to making everything feel funny, even when you’re not laughing. It’s almost Pueblo Home Companion, you know what I mean?

It’s only when you hit the final story in this collection, “Bullnecks and Bracelets,” that things truly take a turn for the dark: Try as he might to bury himself in bodybuilding, drugs, love affairs, and hustling, Israel’s whole life is defined by the disappearance of his twin sister during a solar eclipse when they were very young. No matter where he goes or what he does, he cannot escape that black sun. And this is where “Palomar” becomes what it is–where Gilbert becomes what he is–as surely as The Sopranos became what it was with “University” in Season Three. Whether in terms of family, sexuality, physicality, or deformity, biology is destiny for the people of Palomar, in a way that is almost never true for the Locas (Penny and H.R. excepted, perhaps–and a certain character in “Browntown”). And although biology is obviously among Beto’s primary concerns, destiny is the operative word. I don’t think the Palomarians have the ability to escape the way the Locas do. Not all of them need to escape, mind you–there’s a lot of really warm and adorable and hilarious and awesome stuff going down in Palomar–but whatever walks alongside them in their lives is gonna walk alongside them till the very end.