Archive for the ‘Pain Don’t Hurt’ Category

179. Smart boy

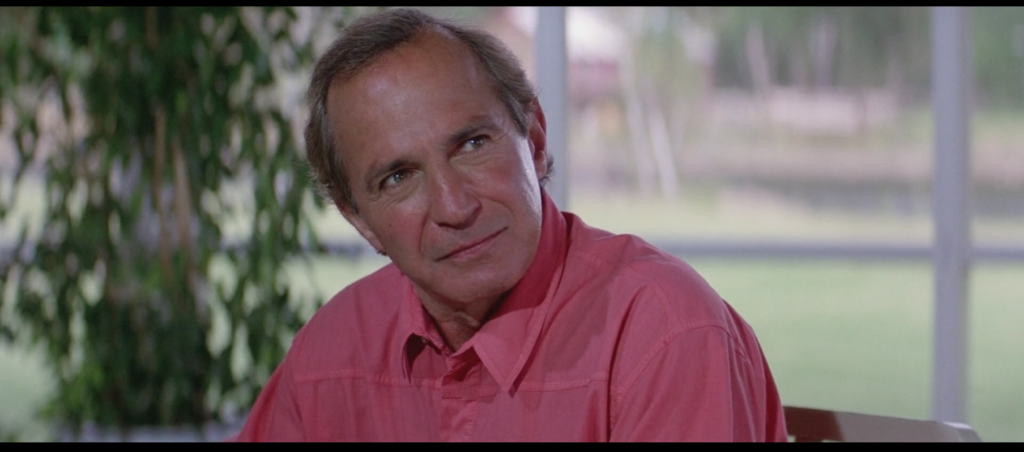

June 28, 2019At the time of Road House‘s filming Patrick Swayze was 36 years old, Ben Gazzara 58. Assuming their characters are the same age that makes Brad Wesley technically old enough to be the younger man’s father, though he’d really have had to make the most of his downtime in Korea to pull it off. Still, 36 is barely a boy’s age in hobbit years, let alone human ones.

Yet “boy” is the diminutive Wesley chooses to employ when favorably comparing the stalwart cooler to his own asshole grandfather: “But you—you’re a smart boy, aren’t you, Dalton? You’re just not too realistic.” He’s intelligent, but a child. He’s not an asshole like Grandpa Wesley, but he’s not a great man like Brad Wesley either. It’s backhanded compliments all the way down.

Or is it? Wesley repeatedly calls his beloved goons his “boys.” And sure enough, before this conversation is through he offers to hire Dalton to bounce on his behalf. It’s an invitation/initiation into the Lost Boys of Jasper that Dalton leaves on the table, but still. Brad Wesley is the only adult in the room, which makes everyone else children in his eyes. He is also the father of Jasper, Missouri, making everyone else his children in his eyes. His destiny, he says, tells him to gather unto him what is his. Are we all that far afield from Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me? For theirs is the kingdom of Jasper.

180. Three Imaginary Boys

June 29, 2019Brad Wesley is not the only character in Road House in whose eyes Dalton is but a boy. Three others label him as such, and they could not be more different in tone and intent.

First up is Red Webster, one of the Four Car Salesmen of Jasper, Missouri. An avuncular presence in the film—literally: He is Dr. Elizabeth Clay’s uncle—he asks if Dalton is “the boy from the Double Deuce” when our hero shows up at his store before it opens to have various parts of his car replaced. Just a friendly, getting-to-know-you inquiry, from a guy calling another guy “boy” because he’s younger and he’s just arrived in town. Here, “boy” connotes “newcomer,” someone who is experiencing the world around him with fresh eyes, and who finds himself welcomed by those around him. Excepting the clientele of the Double Deuce as currently constituted, of course.

Next is Jimmy, Brad Wesely’s right hand and bastard son [source for this claim?]. “Your ass is mine, boy,” he growls, gesticulating for emphasis in case the owner of the ass of which he is claiming emphasis was unclear. Wesley has just stopped Jimmy from taking on a roughed-up Wade Garrett and a fresh-to-the-fight Dalton 2-to-1 in the Double Deuce, the night Wesley’s men blow up Red Webster’s store and Denise does an aggressive striptease to further assert Wesley’s dominance or something. Here, “boy” means a man less experienced, less tough, less dangerous, less of a man; Jimmy will use the term again when he sneers at Dalton’s fighting prowess during their eventual mano a mano showdown. (His father, spiritually anyway if not biologically, Brad Wesley will pick up the ass-owning baton and run with it, by the way, but not before Jimmy returns to that well implicitly when describing what he used to do to guys like Dalton in prison.)

The third and final boy-sayer is Wade Garrett. Staggering into the Double Deuce the night after Dalton kills Jimmy, Wade has been badly wounded in a fight with three unspecified Wesleyan goons. Dalton realizes that if Wade is still alive, it could be that the hammer is slated to fall on Elizabeth. He rushes out to find her, but not before assuring Wade that he will grant his mentor’s wish at last: They will leave this town and never look back, allowing Wesley to win rather than keep up a fight that by rights isn’t theirs. Wade looks up at the younger man and smiles. “Attaboy, mijo,” he says. Mijo, of course, means “son”; this is the “boy” of approval, of pride, of love. This is the “boy” of a dying parent’s love for his only child.

181. Memphis

June 30, 2019“Dalton,” Brad Wesley says. “I have a cousin in Memphis. Tells me you killed a man down there. Tells me you said it was self defense at the trial. But you and I know that isn’t so, don’t we.” Even in a scene as cockamamie as the Breakfast Conference, this series of statements makes an impact.

First and foremost it confirms what to this point had only been treated as part of Dalton’s cooler legendarium—a potential tall tale about ripping a man’s throat out with his bare hands that Hank relates to Horny Steve, and that Horny Steve rejects as bullshit out of hand. Wesley doesn’t mention the unusual method of dispatch at all, as the details do not concern him. What does concern him is that, in his own estimation anyway, he is up against a) a killer, and b) a liar. The former tells him Dalton can be useful; the latter tells him Dalton may be willing to be used.

Second, it shows us that despite all his sangfroid, Dalton does indeed have nerves that can be hit and buttons that can be pushed. He neither confirms nor denies Wesley’s cousin’s report, and a closeup reveals his reaction as muted. It’s only when Wesley claims that the self-defense justification was bullshit that Dalton gets up from his chair, preparing to storm off. Wesley preceded this story by arguing that of course Dalton loves beating people up for cash, that this is both his nature and human nature in general. Telling Dalton this story about his own life, then intimating that they can both sense the truth lurking under the surface, is Wesley’s attempt at turning him into a co-conspirator on this point. Wesley sees a useful man, he concludes that this man may consent to being used, he attempts to paint him into a corner in which he’s being used already, in which his use is a fait accompli. It’s rather deftly done, and that it leaves us not fully sure to what part of Wesley’s version of events Dalton objects is deft as well.

Third, it’s a pleasure to listen to, bearing many of the hallmarks of Road House‘s finest line readings. Ben Gazzara’s voice is a rollercoaster of subtle modulation, a miniature Bleeder Speech. “Dalton” is delivered in his best we are reasonable men, you and I; come, let us reason together voice. “I have a cousin in Memphis” is flatly factual. “Tells me you killed a man down there” swoops upward in register, as if he’s relating an interesting factoid from a wikipedia page he’s reading as he and Denise sit next to each other on the couch after dinner looking at their phones. “Tells me you said it was self defense at the trial” has a conclusory feel to it: Ah, well, that settles that. Then the verbal killshot: “But you and I know that isn’t so, don’t we.” His voice shifts to a level lower than in conclusion, revealing the deeper truth. Despite the sentence construction, this is, in that go-to maneuver of Road House rhetoric, not a question but a statement. They know. They both know.

Fourth…Brad Wesley has a cousin in Memphis.

It’s not the first time Wesley has alluded to family even within this scene; there’s his asshole grandfather, his only sister, and of course his only sister’s son Pat McGurn. (Not to mention his bastard son Jimmy, and no I will not be providing documentation.) So there’s precedent here—just not, more broadly speaking, within the world of action-movie archvillains. I don’t recall any other cousin relationships factoring into the mental landscapes of the big bads of ’80s and ’90s murder-spectacle movies, so this is something of an anomaly.

But how much does this cousin factor into that landscape? Let us first assume the cousin actually exists and is not simply a convenience concocted by Wesley to preserve the integrity of his intelligence network. Do they speak regularly? Does Brad give him or her (pronouns are dropped here, perhaps strategically) the occasional call just to say hello, or vice versa?

If so, how did Dalton come up? Did Wesley happen to mention the name of the new bouncer in town? Was the plight of their mutual relation Pat McGurn the topic at hand?

Or was it brought up deliberately? Did Wesley know some of Dalton’s past haunts, perhaps via the barfolk network into which his goons Morgan and Pat had been plugged for years? Did the cousin hear that a local figure of ill repute had traveled to good ol’ Brad’s stomping grounds?

And who is the cousin? Is it simply some unnamed, offscreen figure, concocted by the writers as a device for relaying this crucial bit of backstory? Or is it someone we’ve met? Someone who figures briefly into the film before this conversation and then returns whence he came to hear Beale Street talk? Someone we witness in Wesley’s company—at his pool party, in his driveway during a postmortem confab about the failed mission to secure reemployment for Brad’s nephew and his own first cousin once removed Pat McGurn, at a subsequent intra-family mission to intimidate Brad’s ex-uncle-in-law Red Webster—who then relays this information offscreen, says goodbye, and then is never seen again?

182. Cousin in Memphis

July 1, 2019Called up my two worst goons and I

Gave them a name

Was down to tell Dalton intriguing news

And say “Christ” three or four times in vain

You smart boy, Dalton

Won’t you come have brunch with me

Yeah we’ll have some idle chit-chat

About your old Class A felony

Got a cousin in Memphis

I got a cousin says you killed a man down on Beale

Cousin in Memphis

The human throat was his Achilles’ heel

This guy’s throat, you ripped it

Then pleaded self defense

He stuck a gun in your face and threatened

So you tore him a new vent

Now both you and I, we know that’s bullshit

And your story isn’t so

The JC Penney? That was me, ask anyone you see

Christ, they’ll all tell you so

Back to my cousin in Memphis

I got a cousin says you killed a man down on Beale

Cousin in Memphis

The human throat was his Achilles’ heel

I’ve got breakfast on the table

And there’s freestyle in the air

And Pat McGurn’d be mad to see you

But my sister-son’s not there…

He’s visiting my aunt in Memphis

Now Jeff Healey plays the guitar

Every evening at the Double Deuce

So I’m heading down to see him

So Denise can cut footloose

She’ll do a little striptease

And then Jimmy’ll start a fight

And he’ll ask if you’ll rip out his throat too

And I’ll say “Christ, I think he might”

Got a cousin in Memphis

I got a cousin says you killed a man down on Beale

Cousin in Memphis

The human throat was his Achilles’ heel

Got a cousin in Memphis

I got a cousin says you killed a man down on Beale

Cousin in Memphis

The human throat was his Achilles’ heel

Called up my two worst goons and I

Gave them a name

Was down to tell Dalton intriguing news

And say “Christ” three or four times in vain

Was down to tell Dalton intriguing news

And say “Christ” three or four times in vain

183. The Third Rule, Verse 6

July 2, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, for the final time, is the third.

3. Be nice (concluded)

Previously:

- The Great Commandment

- The Parable of Someone Getting in Your Face and Calling You a Cocksucker

- Walking the Dalton Path Together

- It’s a Job / It’s Nothing Personal

- Two Nouns Combined to Elicit a Prescribed Response

As our lessons have shown us, there is nothing simple about the simplest of the Three Simple Rules. Be nice: Those two words pack a world of meaning into their duosyllabic totality. Through parable and paradox and painstaking explication of every detail, Dalton slowly indoctrinates his disciples in the six letters (plus a space) that are the true determinant of the Dalton Path’s meandering course.

Naturally, the Dalton Path must include its own Path-annihilating destination.

3 (Revised). Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.

That’s what Dalton wants. He says so. “I want you to be nice…until it’s time to not be nice,” he says, in so many words. This is the second time he’s given voice to his own desires when delineating the Third Rule, the other being “I want you to remember that it’s a job—it’s nothing personal.” We can hereby conclude first that nature of the work as work, as labor, is of central importance. Indeed we will see how this conception of the job allows Dalton both to assert that, as a laborer, he is entitled to all he creates, and how it gives him the detachment necessary to see himself (his self) as separate from the job that his self performs.

But it’s the second half that clues us in here. We recall that in saying “It’s nothing personal,” Dalton was employing the old “If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig” technique: He waltzed into these people’s place of business, fired several of them, told them his authority is absolute, noted what a bad job they’ve been doing, personally insulted them—sometimes via parable, sometimes via insinuation, always indirectly so as to stymie their righteousness in lashing back. If they managed not to take what he was doing personally, then they already will have understood the importance of not taking things personally.

Which brings us back to “Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.”

“Well, uh, how are we supposed to know when that is?” asks Younger, the quietest of Dalton’s new believers.

“You won’t,” Dalton says. “I’ll let you know. You are the bouncers. I am the cooler. All I want you to do is watch my back—and each other’s…Take out the trash.”

We already know that the Dalton Path is a path we walk together. Here, at the end of the path, the point at which the Third Rule gives way to its opposite, where thesis becomes antithesis, where being nice becomes not being nice, is where we receive the most emphatic declaration of our collectivity.

It is not for us to know when the time to not be nice has come. We are but bouncers, seeing through a pint glass darkly. Dalton, the Cooler, will instruct us. And yet the cooler cannot be the cooler without his bouncers. He needs us to watch his back—and each other’s—just as much as we need him to tell us the day and the hour of the not-niceness.

This is all part of the same thought-flow, each point indistinguishable from the last. Without bouncers, the cooler cannot cool; without the cooler, the bouncers cannot bounce. Ad infinitum, world without end, amen.

And what are the Three Simple Rules, if not the cooler distilled to his intellectual essence, the flesh made Word? Time and time again we have seen how when released into a mind willing to receive them, they act independently, engendering the understanding required to understand them as they take their course. Each rule is Dalton made miniature, released into the Double Deuce of the mind, taking out the trash. And within ourselves, we have watched his back all along.

We will not know when the time has come to not be nice. We won’t need to. Dalton will tell us. He already has.

This marks the midpoint of Pain Don’t Hurt. Thank you for reading.

184. Wesley Say Relax

July 3, 2019“Relax, relax!” says Brad Wesley at the precise midpoint of the film Road House—57:02 down, 57:02 to go. He’s telling his guest, Dalton, to chill out about the whole “this guy just sent his goons to pick me up and paraded me past his abused girlfriend so he could sit me down in his breakfast nook and tell me he thinks I murdered a man in cold blood” thing. I’d probably tell him to relax too, if I saw him getting up from his chair in anger and believed him to be a remorseless killing machine!

After Dalton gets up, fuming, Wesley does his RELAX, DON’T DO IT bit and then asks, purely hypothetically of course, how much money it would take to get Dalton to come work for him if he had a bar that needed cleaning up.

“There’s no amount of money,” Dalton says, and storms out.

And I will say this for Road House: The midpoint of the movie—the turning point, if you will—really is the midpoint of the movie.

This scene is where it stops being a job and becomes something personal. This scene is where it stops being time to be nice and starts being time to not be nice. This scene is where Dalton starts to break his own Three Simple Rules. This scene is where the Dalton Path diverges in a breakfast nook and Dalton begins to take the one less traveled by, perhaps because it is littered with corpses. Relax? Don’t do it.

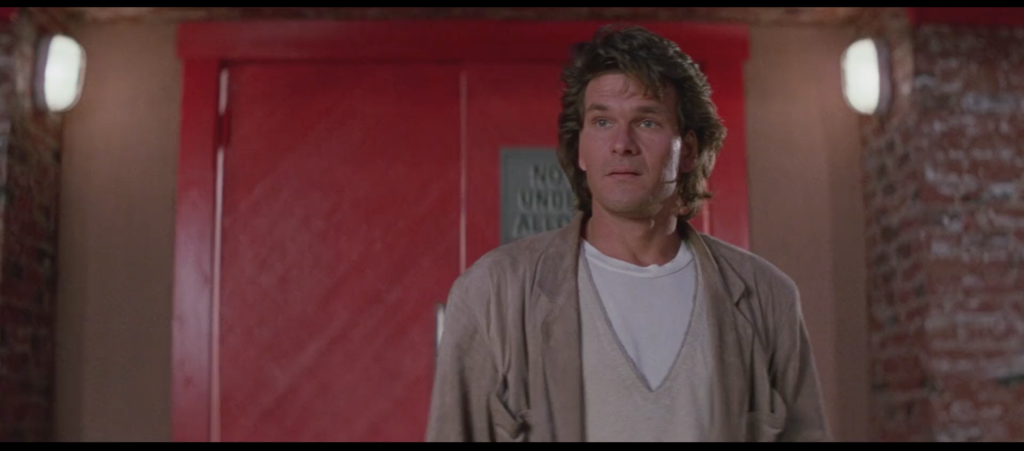

185. “I think it’s time for you gentlemen to leave”

July 4, 2019“I think it’s time for you gentlemen to leave” is the first thing we hear Dalton, the second greatest cooler in North America, say in Road House, the film about him. I’m ashamed, however, to say that it’s taken me over half a year to write about it. To paraphrase George Harrison on Ringo Starr, the phrase looms large in his legend.

There’s a reason I avoided specifying the sentence’s terminal punctuation, and it’s because Patrick Swayze’s line reading defies our understanding of the very concept of the sentence. “I think it’s time foryougentlemen to leave“: Dalton walks up to the scene of a Knife Nerd disturbance and these words come spilling out of his mouth in a controlled burst. “I think it’s time“: Face stoic, he leans hard on the last word, letting them know the time has come for…something; “foryougentlemen”: It comes out like a child sayin “LMNO” in the middle of the alphabet, as if “gentlemen” is but a courtesy he’d just as soon skip past; “to leave“: the initial “t” is hard, the tip of the tongue taking a trip of two goons down the palate to tap, at “to,” on the teeth, and then right into “leave,” emphasis his, the message clear, get the fuck out before he stops calling you gentlemen, you don’t have much time left.

The delivery is magnetic, engaging, evocative of the entire Dalton persona that awaits us, commanding yet polite yet petulant, tremulous with suppressed violence and the strain of high ideals, ready to be peeled back, layer by layer, like an onion, like a daydream, or a fever.

186. [whispering to date while watching Road House when Road House first appears on the screen]

July 5, 2019187. Stitches

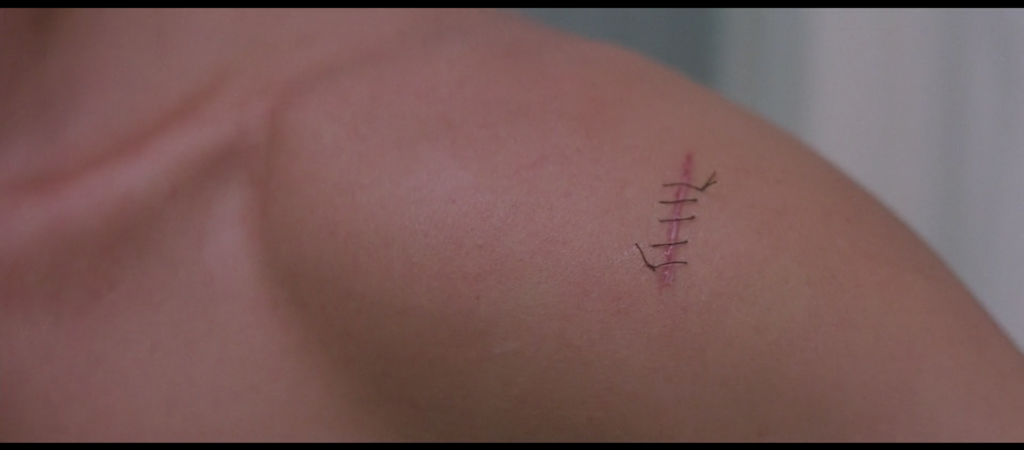

July 6, 2019“Why must a movie be “good” ? Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a beautiful face, huge?” When Mike Ginn wrote this on twitter he could easily have been speaking about Road House, since the beautiful faces of Patrick Swayze, Kelly Lynch, and Sam Elliott are no small part of the attraction and entertainment. (If you find a film studies program that articulates the sensual pleasure of cinema this effectively in two sentences or less, please ask a billionaire to give it a grant.) But in the action films of the 1980s—as in many other genres and many other time periods, but here the tendency is especially marked—there’s another question to ask: Is it not enough to sit somewhere dark and see a beautiful face, bruised?

Sylvester Stallone is one of the strangest extremely famous and mainstream people in Hollywood. I often think of the road not taken when he put out Rocky II and thus gave the lie to the final exchange between Rocky Balboa and Apollo Creed about rematches in the first Rocky film, which would otherwise be remembered as the classic of 1970s New Hollywood that it actually is. But since he is often not just the star of his films but the writer and/or director as well, his idiosyncracies shine through in even the most fast-food slop he serves up. Regardless of how slick, bombastic, and ultimately jingoistic the Rocky and Rambo series wound up getting by the end of the ’80s, in direct opposition to the earthy, low-key, and questioning debuts, they are at heart two separate franchises created by Sylvester Stallone based on the assumption that watching his perfect body get destroyed over and over again was crackerjack mass entertainment. That he was correct speaks to a desire in the audience to see that which we desire abased and laid low. Kink has understood and articulated this forever; cinema can’t really speak it aloud, but it’s there alright.

As I was flipping through my copy of Road House, which is often what I do to start this daily process, I stumbled across this frame of Patrick Swayze’s shoulder with a stitched-wound makeup effect stemming from Dalton mending the knife injury he incurred at the start of the film. At no point does Dalton take a beating that John Rambo and Rocky Balboa would even recognize as such. Yet because of his lithe dancer’s physique (“I thought you’d be…bigger”), the delicacy of his movements, and the coded-feminized prettiness of his face and hair, we feel the shit out of every punch and kick and cut. His penultimate battle, with Jimmy, is to my mind one of the best fight scenes ever filmed not just because of the ace choreography and Swayze’s and Marshall Teague’s almost dangerous commitment to the scene (they realized after the first night of filming that they’d have to pull some more punches if they wanted to successfully complete the damn movie), but because of how Swayze’s shirtless, glistening, fire-illuminated torso radiates physical beauty even as it’s getting pummeled into hamburger. The beating is the spice that brings out the flavor of the dish. So too here with the wound and the stitches, six bold slashes through an unblemished field of bare smooth flesh. The stitches could just as well spell “Kiss it and make it better.” So could the Hollywood sign.

188. That’s Road House

July 7, 2019I wasn’t joking when I joked yesterday that the road house we see when Jeff Healey starts playing the Doors’ “Roadhouse Blues” *is* Road House. Say what you want about the writing of this movie, but there’s almost always some serious narrative logic behind the editing of it—of which image follows which line, of which scene arrives at which moment. We saw it with Brad Wesley’s breakfast, the literal center of the film, before which Dalton is nice and after which Dalton is not nice. We saw it very early on, when director Rowdy Herrington’s credit appears immediately between Terry Funk yelling “DON’T COME BACK, PECKERHEAD!” at a man he just bodily threw through the doors of the Double Deuce and that shirtless yahoo boogieing on down in front of the chickenwire-wrapped stage. And we see it again here, when right after Dalton announces in no uncertain terms that he’ll never work for Brad Wesley, “Roadhouse Blues” plays over the debut of the new, remodeled Double Deuce in the very next shot. The scene that then takes place shows the bar as Frank Tilghman intended it to be—packed to the rafters, everyone happy, no one fighting (or shirtless). The booze is running low thanks to Brad Wesley’s blockade of distribution, but no violence breaks out and nothing breaks up the party. Everything else is going exactly the way the decision to hire Dalton to clean the place up was meant to ensure. Everything works. That’s the endpoint of the Dalton Path. That’s Road House.

189. All Smiles No Blues

July 8, 2019A partial list of things Dalton smiles at during the “Roadhouse Blues” scene in Road House:

- The parking lot

- The crowd waiting in line to get in

- The guy counting attendance

- Jack the bouncer

- The crowd to his left

- The crowd to his right

- The Jeff Healey Band

- The pool table area

- The dining area

- The crowd at the bar

- Ernie the bartender

- His coffee

- The crowd on the dancefloor

- Frank Tilghman

- The prospect of taking care of Frank Tilghman’s problems

And the night is still young for him, too! By the time it’s over he’ll also have smiled at Dr. Elizabeth Clay in his parking lot, Dr. Elizabeth Clay in his apartment, Dr. Elizabeth Clay in her car which he’s driving, Otis Redding on the radio, Dr. Elizabeth Clay on his erect penis, and Dr. Elizabeth Clay nude on his roof. (Otis seems like the odd man out there until you consider his vital role in that particular progression.) None of these smiles are sardonic or wry. None are directed at stop signs torn from the ground and speared through his car windows, or at people who have or soon will have tried to stab him to death. These are genuine smiles of happiness, from a man who finds himself surrounded with the best things in life: happy crowds, good drinks, admiring proteges, soul music (blue- and brown-eyed varieties), Kevin Tighe, open-roofed motor vehicles, public nudity, the welcoming sex organs of a beautiful woman with a doctorate degree. The Dalton Path leads to a far green country.

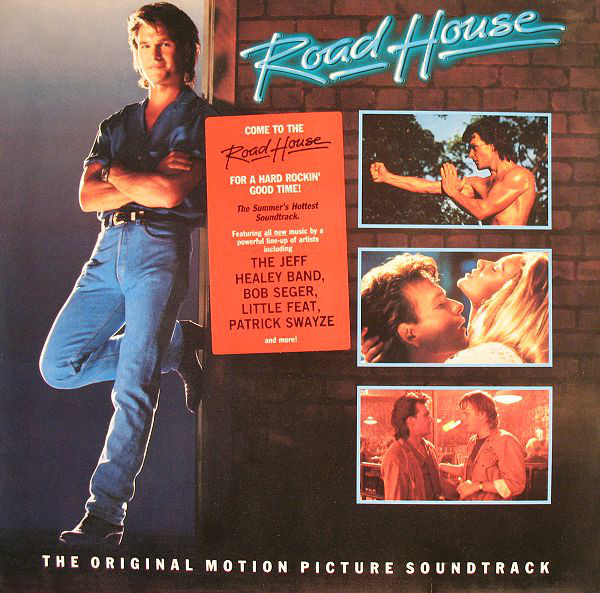

190. Soundtrack

July 9, 2019The thing you need to know about Road House: The Original Motion Picture Soundtrack is that it’s not what you think, or perhaps even hope, it is. It’s not a wall-to-wall collection of all of the Jeff Healey Band’s performances from the film. Four of their songs make the cut, but one (“I’m Tore Down”) is only minimally memorable from the movie, and several of the big showstoppers (“Travellin’ Band,” “White Room,” “Knock on Wood (feat. Kathleen Wilhoite)” are nowhere to be found. There’s no snippets of the High Hollywood action-movie score by Michael Kamen, the late great film composer who counted the original Die Hard trilogy and Metallica’s orchestral album S&M among his achievements. “These Arms of Mine” by Otis Redding? That’s in there, thankfully. Alabama’s “(There’s A) Fire in the Night”? No joy.

What you get is a mixture. There’s those four Jeff Healey tracks, including “Roadhouse Blues” and “Hoochie-Coochie Man” from the Denise striptease and Bob Dylan’s self-plagiaristic “When the Night Comes Falling From the Sky.” Otis is on there. Most of the songs are covers—Dylan, the Doors, Willie Dixon, Willie Nile, Maria McKee by way of Feargal Sharkey, Fats Domino. There are at least four songs on here, including two performed (and one co-written) by Patrick Swayze himself, that I don’t think are in the actual movie at all.

You could complain about that, were you so inclined. Me, I’m happy to hear Patrick Swayze’s surprisingly high breathy singing voice over massive ’80s production tricks (giant drums, “ay-oh ay-oh” backing vocals, little glittery synth fills). And anyone who played Prince’s Batman album and Madonna’s Dick Tracy tie-in I’m Breathless as often as I did in middle school knows this much is true:

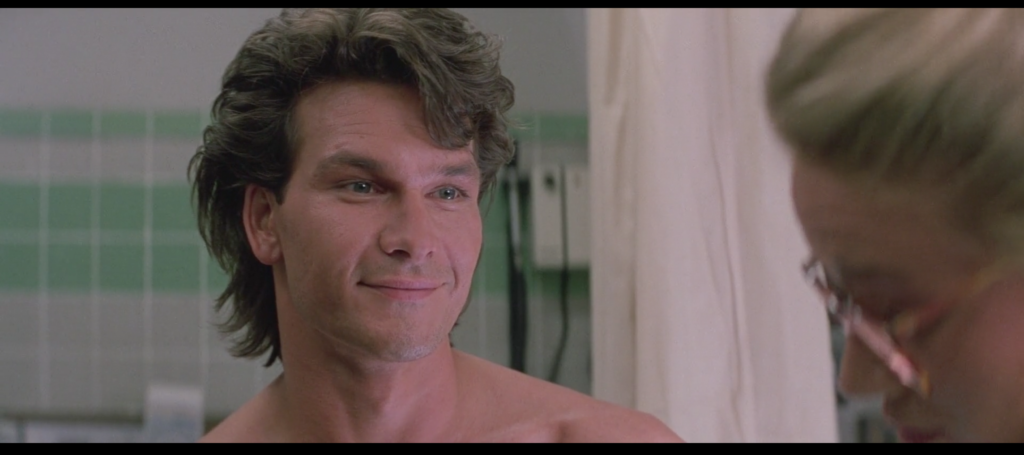

191. Pain don’t hurt revisited

July 10, 2019When I first addressed “pain don’t hurt” I did so from the perspective of Dr. Elizabeth Clay. She’s in the process of mending a knife wound in the side of a man who has to be the single oddest person she’s ever treated, and he drops that on her? Once you’ve seen the whole movie, once you know what we know about her—her reaction to Dalton’s violent job, her feelings for him as a person she cares about and is more afraid for than afraid of, her past relationship with Brad Wesley for whom the opposite is true—you know that line probably knocked her on her ass a bit. Enough to get her to accept his offer of a date for coffee, anyway.

But look at him! Look at the shit-eating grin on the face of James Dalton after he tells a trauma surgeon or whatever she is that pain don’t hurt. Actually, scratch that, just look at the grin, the smile, the smiling eyes too. Patrick Swayze, the god, at work, showing you just how smitten he is with this woman already. I’ve seen lovers in real life look at each other when the other isn’t watching, and that’s what it looks like. Goofy, glad, unguarded. It’s moments like these when you take off your metaphorical shirt and expose your figurative wound and think “I trust this person to care for this” and just smile at how lucky you are to have found them.

It changes how we read Dalton’s self-evident self-satisfaction when he says his three-word maxim, doesn’t it? Because he’s proud of the line, and he’s even prouder of the lifetime of experience in word thought and deed that led him to draw that conclusion, but he’s proudest of having said it to this fascinating woman.

I’m not saying he’s like a little boy trying to please Mama or a puppy gazing with love at his master. I don’t think Dalton feels subordinate to her in that way any more than he feels subordinate to anyone else save Wade Garrett. (Man, that’s an essay waiting to happen.) I’m saying he’s pleased to show her the best of himself, in every respect: his perfect body, his sharpened mind, and his mastery over both of them. He’s happy to impress her. He’s happy to be impressive. Judging from his face I don’t think he’s ever been happier to be impressive. He’s finally found someone worth impressing.

192. ‘Whiskey’s Running Low’: The Tragedy of Keith David in ‘Road House’

July 11, 2019The man in the red shirt is Keith David. You may remember him from his roles in John Carpenter’s The Thing and They Live, two of the best science fiction and horror films ever made. In each he plays the main foil to the protagonists—rough-hewn salt-of-the-earth working-class white-guy types, with tough-as-nails attitudes and impressive heads of brown hair, who find themselves unexpectedly drawn into conflict with forces larger than themselves. Road House, you’ll note, stars Patrick Swayze as a rough-hewn salt-of-the-earth working-class white-guy type, with a tough-as-nails attitude and an impressive head of brown hair, who finds himself unexpectedly drawn into conflict with a force larger than himself.

Naturally, in Road House, Keith David plays a bartender whose sole line of dialogue is “Whiskey’s running low.”

That’s not quite all there is to the role. His name, uttered by both Tilghman and Dalton in this scene, is Ernie, and getting named is an honor precious few supporting characters in this film enjoy. He’s mentioned by name more than all the other bouncers and bartenders and waitresses still employed by the Double Deuce at this point in the film combined, save for Carrie Ann, who says her own name and gets it yelled at her by Pat McGurn. Everyone else? Bupkis.

What’s more, he’s listed with a surname in the closing credits. This too is more than can be said for virtually anyone in the movie. Jimmy, for example, went by “Jimmy Reno” during filming—you can find interview clips with Patrick Swayze in which he calls that character by name, it comes up frequently in interviews with actor Marshall Teague, and it’s in the IMDb listing—but is merely “Jimmy” in every official respect. Dalton himself only gets a mononym unless you inspect his medical file.

Most strikingly, Keith David appears in the opening credits. He’s billed fifth, after only Patrick Swayze, Ben Gazzara, Kelly Lynch, and Kevin Tighe, and just before Kathleen Wilhoite. The actors who play Emmett, Red, and Denise all get lumped together in a single triple chyron, which is fair enough. Sam Elliott gets a “And SAM ELLIOTT” to conclude the cast listing, which is appropriate. Jeff Healey slides in later on via an “Featured Music Performance by The Jeff Healey Band” slug. Other characters you think might reasonably get listed up front—Jimmy, Tinker, O’Connor, Ketchum, Morgan, Pat, Jack—aren’t there at all. Ernie’s fellow bartender, who’s there since the beginning, is entirely uncredited.

If you’ve watched David deftly dance between antagonist, supporting character, and stealth protagonist in The Thing, or if you’ve watched his world-building alley fight with “Rowdy” Roddy Piper in They Live, you probably have some questions about all this. God knows I do.

As best I can ascertain, partially from half-remembered poorly sourced comments in various Road House posts across the internet, and partially based on my own conjecture, is that Ernie Bass was originally a much more prominent character, the bulk of whose storyline wound up on the cutting room floor. I suspect he was a famous bartender, whom Dalton brought in to elevate the Double Deuce’s standing further still—surrounding himself with a surrogate family of old friends which also included Cody, his bandmates, and Wade Garrett. While the material was cut for time, contractual obligations kept David in the picture and in the credits.

A questionable decision, to be sure. Were David cast in a fighting role he’d be an invaluable asset to the film, and even as simply a gnomic presence dispensing basso profundo wisdom behind the bar he’d be a huge get. Instead? He hands Dalton a coffee with a nod of acknowledgement. He tells Tilghman “Whiskey’s running low.” He hands Dalton a phone. He looks at Wade Garrett. He looks at Wade and Dalton together. Exit Ernie Bass, pursued by an editor.

193. Why won’t they deliver

July 12, 2019Dalton may be all smiles, but Frank Tilghman has frustration to burn. Whiskey’s running low, you see, and oh how steamed he is about that. “I finally get this place just the way I want it and now we’re running out of booze,” he spits, with a sardonic half-laugh for emphasis at the end. “I’ve called every supplier I know,” he continues. “Why won’t they deliver.”

Expected a question mark at the end there, didn’t you? Yes, one would, wouldn’t one. But in that standard Road House flourish, the question is delivered as a statement. Yet something’s off here. This isn’t Doc or Dalton or Wesley supplying an answer they believe they already know—that Dalton feels entitled to collect money for beating people up, that Doc thinks Dalton’s life is too ugly to be a part of, that both Wesley and Dalton know he committed a crime not acted in self defense when he killed a man. Frank’s affect in every respect but the lack of a rising tone of voice indicates that he has no clue why people are refusing to sell him liquor anymore. It’s just a little thing that he phrases it as if he knows, right?

Well, Dalton knows the answer, that’s for sure. “Wesley,” he says authoritatively, before grabbing the phone and making a call we will later be able to deduce was to his mentor Wade Garett for help. It’s interesting, though, to watch Tilghman’s face here. When Dalton answers his “question,” he doesn’t react at all. No surprise, no “I knew it,” no “Jesus, he’ll stoop to anything,” no “goddamn that bastard”—flat. He just takes it right in stride.

Almost. His question is a non-question, yeah, and his response to the answer is nonexistent. But when Dalton turns toward the phone, look at Frank’s eyes. Follow them as he gives Dalton a quick once-over. It’s not like he hasn’t seen Dalton before, and as much of a pleasure as it is to look at the guy it seems like Tilghman’s mind should be on other things right now. Things like the matter of the liquor blockade of his bar, the culprit behind which Dalton has just named and against whom he now appears to be placing a call for aid.

Unless that is what’s on his mind when he looks Dalton up and down while the cooler isn’t looking. But why would that be? Why would Tilghman size Dalton up while thinking about Brad Wesley’s role in the Double Deuce’s plight? Why would he want to get a good look at the man who just informed him Wesley is responsible? Why would he sneak an analytic glance at the man he’s effectively placed in charge of battling Brad Wesley for control of the town, after feeding that man the information required to initiate the next round of hostilities? Why would he want to get a very close read on Dalton’s affect, his body language, the clues he might give as to how deeply he’s thought this matter through? Why did he not react with surprise when Dalton told him what he’d figured out? Why did he supply the question as if he already knew the answer himself? What is the specific concern regarding Dalton, and Wesley, and his own relationship with both men, that leads Frank Tilghman to act so suspiciously?

‘Road House’ on Netflix: A Guide to the Greatest Bad Movie of All Time

July 12, 2019Since I first saw the movie with a bunch of drunk, high, hooting and hollering friends over a decade ago, I’ve watched it dozens of times with dozens of people. I never get tired of the bone-crunching action, the sweaty neo-western sex appeal, the cockamamie dialogue (“Are you gonna fight, dickless?” “I sure ain’t gonna show you my dick!”), the peculiar performances, and the overall vibe that anything can happen at any moment. I always find new things I never noticed, or old things I never fully appreciated.

In other words, this great bad movie functions, in a lot of ways, like a great great movie. I’ll never stop watching it. Now, thanks to its presence on that big red streaming service, you never have to stop watching it either.

Road House is on Netflix now, so I wrote a guide to its wonders for Decider.

194. Gaucho

July 13, 2019I’ve paid close attention to the “Roadhouse Blues” scene because it’s the Road House Universe’s ideal state. It comes right after the centerpiece scene, in which Dalton switches from being nice to not being nice, from treating it as a job to treating it as something personal. It features “Roadhouse Blues” by the Doors, essentially the film’s title track. Dalton spends practically the entire scene smiling, indicating all is right with him. There are no fights, no arguments, no interlopers. The whiskey’s running low, but it’s not running out, and Dalton’s going to take care of it with that phonecall of his. Frank Tilghman’s actions bear special scrutiny, as discussed, but that only emphasizes the scene’s importance. After all, even he admits he has the place just the way he wants it. Everything going on here is important.

So what’s with all the gaucho hats?

Not one, not two, but three separate revelers are wearing wide, flat-brimmed black hats as they dance and carouse. The young lady in green is easy enough to miss until the woman in maroon and the gentleman in the bolo tie leap out of the screen at you as the camera whirls around them while they dance and you’re like “wait—are these…different people dressed like Zorro?” The answer is yes, they are. (Technically Zorro wears a Cordovan sombrero, which is of a different provenance and region than the gaucho hat, but the two have blended together over time in the public imagination so I’m using the terms interchangeably. I hope you’ll pardon this slight license. Clarity trumps strict accuracy sometimes, that’s just how it works. It’s a job. It’s nothing personal.)

Why are three different people wearing black gaucho hats, though? Is this a cue that Dalton is a Zorro-esque figure, wealthy due to the proceeds of his in-demand cooling services yet still a man of the people, going outside the law to defend them from the depredations of bandits and landowners? I think that’s possible. I think it’s also possible that the costume department had a lot of these because someone was like “It’s kind of like a Western” but cowboy hats were decided against and this was the compromise. I think it’s possible that the hats were considered on-trend, as a little research indicates Yves Saint Laurent was incorporating them into his line at the time. I think it’s also possible that there’s no rhyme or reason to it whatsoever, and that a crucial tone-setting scene in the film Road House just so happens to have three people wearing black gaucho hats right in front of the camera. Bodacious cowboys such as themselves will always be welcome here, high in the Jasperdome.

195. Roadhouse Blues

July 14, 2019The Doors are good. They’re a good band, I’m sorry. Break On Through, Light My Fire, Touch Me, L.A. Woman, People Are Strange, Alabama Song, The End, Riders on the Storm, Love Me Two Times, Hello I Love You, Roadhouse Blues—guess what, that’s a good band! That’s more bangers in four years than Eric Clapton has across all of his projects in a decades-long career combined (for the record: Layla, Bell Bottom Blues, White Room, Tales of Brave Ulysses, Crossroads, Sunshine of Your Love, I Feel Free, Badge, While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Cocaine, and most of those were written by people not Eric Clapton), and I’m not even digging particularly deep. It’s not a Creedence Clearwater Revival’s contemporaneous California run of absolutely miraculous hitmaking, but it’s up there. The insistence that the Doors are a gigantic joke, a dorm-room poster posing as a band, a faux-poetic wet fart—it’s childish, tbh. It’s jejune. It’s “except rap and country,” it’s “Ringo was a bad drummer,” it’s a YouTube comment complaining that today’s music just can’t compare. It’s so, so freeing to leave it behind and fucking bellow YOU KNOW THAT IT WOULD BE UNTRUE! in that final verse as you sing along in the car or just shred BREAK ON THROUGH TO THE OTHER SIDE! at karaoke or whatever. Godfathers of goth along with the Velvet Underground as well. If the Doors were good enough for David Bowie, who loved them, they’re good enough for you too. We have Kiss and Bon Jovi and the Eagles (excepting the song Hotel California and the solo stuff) to kick around. Leave Mr. Mojo Risin’ alone!

I say all that to say this: The Jeff Healey Band really kill it on “Roadhouse Blues.” It’s the most natural fit possible for the movie (duh), for Healey’s more high-energy Stevie Ray Vaughn thing, and for a solo so hot you can all but smell smoke rising from the guitar he holds on his lap. It also loses the scat-singing portion of the song, which is probably one of the reasons you hate the Doors if you hate the Doors. They do it well enough that you could actually conceive of a full nightclub dancing to “Roadhouse Blues” by the Jeff Healey Band, and I mean dancing their asses off, or their gaucho hats, whichever comes first, which they do. LET IT ROLL, BABY, ROLL! LET IT ROLL….ALL NIGHT LONG!

196. Hotbox

July 15, 2019At the end of a long, close to perfect night, the Double Deuce is smokin’. Literally. After the evening represented by the “Roadhouse Blues” scene winds to a close, Dalton stumbles through the big red double doors of the Double Deuce in a cloud of smoke. He rubs his eyes, as if they’re dry and irritated. He breathes out a plume of smoke himself. “Cigarettes and exhaustion” is surely what director Rowdy Herrington and company were going for; “Raindrop, drop top, smokin’ on cookie in the hotbox” is what many a viewer receives. If you’d slapped some designer sunglasses on him, replaced his shapeless beige sport jacket with a fur coat, and shot this in slow motion it’d look like an old Snoop Dogg video. That image and vibe is certainly preferable to the alternative, which is that to get rid of the smell of cigarettes he’d probably need a Silkwood shower. But he’s not one to get rid of the fragrances of nature, to use Emmett’s memorable phrase, and in Dalton’s world the constant presence of lit ciggies is as natural as it gets. More than once we see him light up without even bothering to put a shirt on first. The man has his priorities. And you know what they say about where there’s smoke.

197. Whatever happened to predictability

July 16, 2019What you’re seeing here is the look on Dalton’s face just after he staggers out of the smoky Double Deuce and finds Dr. Elizabeth Clay waiting for him, and the look on Dr. Elizabeth Clay’s face as she looks back at him while leaning back against her car one frame later. I don’t think you need to be an expert analyst of body language or facial expressions or human mating rituals to figure out what’s going on here, and what will be going on shortly hereafter. The Doc is about to get lucky, and Dalton feels lucky about it. That’s predictable enough: They’re both right, as it happens. But how it happens—ah, friends and neighbors, there’s the rub. (The rub against a rock wall, specifically.) It will be absurd, romantic, laughable, red hot, impersonal, extremely personal, erotic, uncomfortable, uncomfortably erotic, erotically uncomfortable, giddy, bold, slightly impractical, intensely physical, eminently watchable. It will be, in short, the Road House of sex scenes. It could be nothing else.