[Editor’s note: This is one of a series of interviews I’ll be posting that were rescued from WizardUniverse.com’s now-defunct archives. Originally posted on August 18, 2007.]

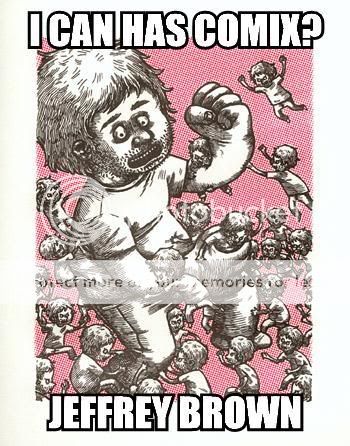

I CAN HAS COMIX?: JEFFREY BROWN

SUB: The ‘Incredible Change-Bots’ creator talks Transformers, his new Top Shelf series, directing for Death Cab for Cutie and why he’s so interested in sex

By Sean T. Collins

The night she first met Jeffrey Brown, a friend of mine went home and created a T-shirt that read “JEFFREY BROWN’S NEXT BOOK.”

It’s certainly hard not to be won over by Brown’s so-called “Girlfriend Trilogy” of graphic-novel autobiographies, the work for which he is best known. In Clumsy, Unlikely and Any Easy Intimacy/AEIOU, he chronicles the major and minor events in three separate relationships with uncensored honesty and humor, in the process creating three of the most instantly relatable comics in recent memory.

But there’s more to Brown than the autobio beat: He’s also a laugh-out-loud-funny humorist whose gag strips grace the collection I Am Going to Be Small, and who’s taken parody shots at superheroes with Bighead, his own brand of sensitive autobiography with the ultra-macho Be a Man, and this summer’s breakout sci-fi stars the Transformers in The Incredible Change-Bots, out next week from Top Shelf. Offbeat contributions to anthologies like Mome and a hilarious homage to his cat Misty in the hardcover Cat Getting Out of a Bag and Other Observations further push the boundaries of Brown’s deliberately sketchy style.

The extremely prolific Brown put down his pen long enough to spill the beans on his new upcoming comics series, his next graphic novels and just what those ex-girlfriends have thought about being immortalized in Brown’s books.

WIZARD: What kind of cartoonist would you describe yourself as? You’ve split your time evenly between a lot of different genres: autobio, parody, gag strips, fiction…

BROWN: Well, when I tell people what I do, I usually say that I draw autobiographical comics, just because usually when I’m telling people, they’re people who don’t really know that much about comics other than the superhero stuff. So that lends some amount of respect to it or something. But it is pretty half-and-half. I guess I would also maybe not want to be trapped in one element so much. I’m half-humor and half-autobiographical–although I guess the autobiographical is humorous too.

I guess that depends on your biography.

BROWN: Yeah. It depends on which part of the book you’re reading.

So is that a conscious choice on your part, not getting stuck in one genre?

BROWN: Well, yeah, partly conscious. There are definitely times where I go back and forth just so that I don’t get too bogged down in the autobiographical. One of the reasons that I did Bighead when I did was that I was writing Unlikely at the same time. It was a way to do something lighthearted and have my mind go somewhere else so that it didn’t get so insulated. But at the same time, I mean, I do genuinely really enjoy doing those other parodies and kind of letting loose with things. It’s definitely something that I make a conscious effort to do, but hopefully it’s something that I do to some extent anyway.

I guess that question first occurred to me when reading the comics you did for anthologies like Kramers Ergot, Drawn and Quarterly Showcase and Mome, which didn’t really fit into either of the Jeffrey Brown modes that we’ve come to know. It’s not Clumsy or Unlikely or AEIOU, and it’s not Bighead or Incredible Change-Bots or I Am Going to Be Small. That kind of work falls between the two poles of what you mainly do.

BROWN: That’s probably not conscious. You’re right. I never really thought about that, actually. I think maybe what it is…I mean, I have a lot of interest in exploring the autobiographical work and that I have a lot of interest in finding these parodies and more straightforward funny books. I think that when I’m doing something for anthologies, you don’t have the same kind of space to work with. The ideas that I use for the anthologies are things that I wouldn’t expand out into a whole book. Then it tends to be these kind of weird ideas that come up less often, that are sometimes a little experimental in form. Essentially, the stuff in Mome was just kind of me letting my mind babble a little bit.

So it’s tailored to take advantage of the short-story form?

BROWN: Yeah. I think that for me to do autobiographical stuff in short form is more difficult because I think that it becomes this lamenting thing, and you just end up with literally short funny pieces or something. I don’t think that it’d be as interesting. Then for the parody stuff, there are a few things like the “Cycloctopus” story, but that was for Project Superior, a superhero anthology, so it fit really well. It’s just easier when you’ve got a smaller space. You can kind of fool around, but there is a cutoff point and you know that you can escape at some point.

This also brings to mind the fact that you’re really, really prolific. It seems like you’re constantly drawing; I’ve gone out to dinner with you and all of a sudden I’ll turn around and you’ve got your sketchbook open and you’re drawing. Is it important to you to keep working and constantly produce comics?

BROWN: It’s not so much that I feel any kind of need to, at the end of the day, have a certain amount of pages published. It’s such a habit for me, though, that I start to get itchy when I’m not drawing a lot. Also, I have to keep coming up with ideas. I don’t know if it’s impatience or what, but I need to get it down quickly. If it’s an idea that I feel really strongly about, a lot of times if I don’t do it shortly after I think of it then I lose interest and I can’t do anything with it.

As an artist, you were first interested in fine arts.

BROWN: Yeah.

Yet your comic style sort of evolved into this…I don’t know. Is lo-fi a word that you would accept as a description?

BROWN: Yeah.

Is that to enable you to keep drawing and keep getting ideas down rapidly?

BROWN: Yeah. Part of it was just in response to fine art, because I was in art school and was getting so tired of overthinking everything and having all of this baggage to making a work of art, so I wanted to go back. Like, when you’re a kid you can just sit down and draw and draw. You’re not worried about things other than just trying to express something on paper. Part of it was just trying to capture that kind of feeling again. The other part of it was that my style does come out of wanting to be fast and sketchy. I guess that part of my philosophy of drawing is that when you’re not overworking a drawing, when you’re really just going at a certain speed, it becomes more expressive and more immediate because you don’t have time to hide your flaws. You don’t have time to tinker around with things. So, in a way, the meaning behind the drawing is kind of purer somehow because it’s unedited.

That reminds me of the indie-rock aesthetic, and it seems as though music is influential in your creative process. Do you listen to stuff when you work?

BROWN: When I can. I usually have it in the background, though I haven’t been lately. I used to draw in coffeehouses a lot, so there would be music playing and then you would have the additional background noise of people talking and people bustling around. Now I’m drawing at home a bit more, and if I’m by myself I can have the TV on and the stereo on at the same time. Usually what I do is I turn the volume down on the TV so that I can just barely hear that, and then I turn the music up, although if anyone else is there, most people start to get really freaked out by the overstimulation. Music is definitely something for me. Also, I think that music is deep into comics, because when I’m driving a lot of times I’ll just be thinking about whatever project I’m working on. So I’m driving and listening to music and also thinking about things. It’ll often deepen things even before I start drawing.

My therapist told me that when you’re driving in your car it’s a little bit of a sensory deprivation chamber, so when you listen to music in your car you tend to react a lot more intensely than you might outside. It tends to spur those deep thoughts.

BROWN: Yeah, that makes sense.

I kept wondering why I was getting so depressed: I was driving home from work listening to Azure Ray, and I’d see some roadkill and I’d want to cry. Then she explained to me how that worked.

BROWN: [Laughs] Yeah, you just need to switch the CDs that you’re listening to.

Having seen your sketchbooks, and occasionally some of the drawings that you put into your one-man anthology collections or even the cover for Bighead, you do have a style that is a lot more rendered and less sketchy and dashed off.

BROWN: Yeah. I’m fairly selective [about using that style]. Part of that is that I never want to be at a point where it becomes style over substance. I also don’t want people to get too caught up in looking at the visuals when they’re reading. So the cover is a good place to do the more rendered work. That’s some of the reason why the superhero stories tend to be a little more rendered. The way that they’re reading isn’t so internal, at least in my superhero stories, so I’m not as worried if the people are looking at the visuals a little bit more. Also, with the superhero stories, there are opportunities for more spectacular visuals just because it’s a fantasy. The other reason, too, is that the way that I draw the autobiographical books with these kinds of simple figures with these claw hands, there’s something about that I find kind of visually amusing. There’s something about bending arms and the physics of the room not working. There’s something about that offness that I like. If you’re drawing superheroes, you can draw them doing crazy, fantastic things. If you’re telling a story about real life where someone is walking down the street, there’s not that opportunity. Extracting the anatomy of people and using the bendy arms and things like that, that’s kind of a way to keep that in the books.

So it’s less a Scott McCloud-type thing in terms of reader identification with cartoony characters and more that you just find the look of it amusing and entertaining?

BROWN: There might be an element of the McCloud theory. I’ve actually fooled around a few times with the idea of drawing a story in a more realistic style. I think that for me what it comes down to is, for one, the more realistic the drawing, the less enjoyable it feels. I want to keep the books lighter; even when there’s something serious happening, in terms of the story, visually you can still have it be funny. There’s something that my instinct tells me: The way that I draw characters is more likable than these realistic characters. I also think that when you’re simplifying and abstracting characters like that, they do become somehow more identifiable with more people. They become a little bit more everyman than they would be otherwise.

As you’re talking about this, I keep thinking about your cat Misty in Cat Getting Out of a Bag. You drew her really cartoony, so she’s kind of an every-cat.

BROWN: Yeah.

Is there such a thing as an every-cat?

BROWN: [Laughs] There must be. There must be.

Which reminds me: I don’t know if I’d have recognized you if all I had to go on was your drawings of yourself. For example, in real life you’re pretty square-jawed, while Cartoon Jeffrey Brown has this sort of round head and not much of a chin. So two questions: First, why did you draw yourself like that? And second, since you’re obviously drawing real people who exist and whom you know, how much does that carry over with the other people in your autobiographical comics? Is getting their likenesses down important, or do you change things?

BROWN: Part of that is that just over time it’s become more stylized and so it’s kind of gotten away from any kind of consideration of looking like me or not. If you look in Clumsy, too, in that book more than any other book I wasn’t concerned with kind of capturing the likenesses and was just almost making these sort of symbolic figures for early characters. Long black hair or stubble would be more of an identifying characteristic than anything else. Now I tend to work a little more towards making the people closer to their likeness, but at the same time it’s more about maybe capturing the feeling of the person. It’s not just about what their personality is, but what my relationship to them is. In that way, it’s something I’m writing about for me, which is more important than whether it actually looks like them or not. People seem to be split actually on how much I look like my drawings. Some people tend to think that I look a lot like how I draw myself, and then other people seem to think that I don’t at all. I used to think that the more you knew me, the more my cartoon counterpart would look like me, but I don’t know that that’s necessarily true either. For someone reading the books, they don’t really need to know what people really look like. In that sense it’s kind of like if they don’t know me, the books might as well be fiction. I think that there’s something about knowing that something is real and true to life that people somehow find attractive, that quality in a book. But I don’t know if that carries over into what things look like.

I see what you’re saying. Is it a voyeuristic quality, do you think, that attracts people to reading that sort of stuff?

BROWN: I’ve thought about this, because there’s the whole scandal of James Frey where he wrote this book [A Million Little Pieces] and presented it as his memoirs, and it turns out that there were some things made up and some things that were really exaggerated. There was a class-action lawsuit and people were getting money back from the book. I think that maybe what it has to do with is something internal in humans that is about not getting fooled, or feeling that there’s an element of trust that needs to be there. Finding out that “Oh, that’s not really how it was” alters their perception, because when they’re reading something, especially when they’re reading autobiography, they’re reading it relative to their own experiences. So, when they find out something like “James Frey went through all these things,” they put that into context with their own past. Then they find out that he’s really something else. That undermines their understanding of human life, their experience. There’s something about that, needing to know whether it’s really true or made up.

As an artist it’s one thing, but as a writer, how important is the accuracy of how you depict events?

BROWN: Well, I’m maybe a little less anal about it now, but I do try to keep things…like, everything I’m writing is true, but things like what I’m leaving out and the timing of things and how I’m presenting things, that’s kind of the art of it all. It’s still important for me, in the autobiographical world that I built up, that it’s true to life, because once you start undermining, or if I were to write something that undermined one story, then it would bring the rest of the work into question too. At the same time though, in terms of timing and characters, once in a while just to not have so many people in a story I might have one person fill a role that was originally two people. I’m not putting words into anyone’s mouth, but how I set everything up can really influence how people are interpreting the story or whether or not I’m expressing the ideas that I’m trying to get at.

Do you think that knowing what you do for a living influences the behavior of people around you at all?

BROWN: I don’t really think so. I mean, for the most part, for people who know me, the books become this separate thing. People will joke sometimes, like, “Oh, you better be careful. He might write about that later.” But the minute that someone says that I might write about something is like a sign to me to not write about it because then there’s something. It’s almost like the people in the situation are too aware of the situation. So I try to write about things from an outside perspective, even though it’s autobiography. I still try to approach it from somewhere else, where there’s a different perspective than being in the moment. The people I’m friends with and the people that I spend the most time with know that. I certainly don’t live my life any differently. I don’t do anything with any kind of plan like, “Now this is something that I might write about later.” If I take a trip somewhere, maybe after the trip I’ll come home and be thinking about that, and it might be interesting and mean something on a more significant level, and I might want to write about that. But I don’t say, “Okay, I’m going to go to New York so that I can write a story about New York and what happens there.” Nothing like that.

So you’re not taking mental notes–or actual notes–as you’re doing things?

BROWN: I do always write from memory, and more often now I’m also writing as if more time has passed. I’m starting to work on a high school/college/art school memoir, so there’s quite a bit more distance in time from the events. I never keep a diary. My idea is that our memory is an editor for us, so when we’re sitting down and thinking about a relationship that we were in, our minds pick certain things out. We don’t always know why, but somehow those things are what become important about that relationship. On the one hand I use that as a tool: using memory as a way of editing things and getting at what’s significant in our experience. Then at the same time it’s also something that I’m interested in, the idea of how our memories work. It’s really interesting to me, why we remember some things and why some things take on such significance to us when often they’re not the biggest events.

One of the interesting things about your autobio comics are the way that they bounce back and forth between events that are fairly momentous within the context of a relationship and little moments that end up almost as important as a first kiss or a breakup.

BROWN: Right. There’s also the fact that most of my time is made up by these inconsequential moments. It’s like stopping to smell the flowers. Those things are important. Years later, when you think back on them, it might be something that you did every day and at the time was routine, but now when you look back it, it does mean something more to you.

Is that why in your first book, Clumsy, you told the story out of chronological order?

BROWN: Yeah. On the one hand I didn’t originally plan on writing just about the relationship. I wanted to collect stories that I would tell my friends–I’d be at work talking to someone, like, “The other day this happened”–so I was just going to take all of those stories, and the first few were about this relationship. Then I realized that I had enough of these stories about the whole relationship. I wanted to let my mind pick the order because it interesting how it had started to go back and forth. I think this is how we think about relationships. When we put it in our heads, it’s like, “Oh, here’s this really great first moment.” Then we might think, “There was this one time, it wasn’t anything special, but we went to dinner.” Then you think, “Then there was this one time where I was really pissed off.” You just go back and forth between these different feelings. I wanted to organize it in that same way. How our minds wander is how the book wanders.

Is there a reason why you stopped doing things in that way for the autobiographical projects you’ve done since then?

BROWN: Not specifically. With Unlikely, I definitely wanted to do something almost surgical in its chronology. That was because the one idea that I really wanted to write about was how I felt about losing my virginity. [I wanted to] capture the feeling about that one event. To set up the feelings around that I needed to do things chronologically and build up to it and then show the aftermath. The book that I’m just finishing up now, which is a collection of shorter autobiographical pieces, jumps back and forth in chronology too, but each story is from 10 to 80 pages and each story in itself is chronological. That gets back to the same structure of Clumsy where the context that things happened in isn’t necessarily the context that we put them in when we organize them in our minds. When we have things rearranged, that’s what heightens their significance to us–where they sit amongst the other things in our minds.

In Unlikely and elsewhere, you’re not pulling any punches when it comes to sex. Actually, that’s one of the most striking aspects of your work. Why sex?

BROWN: Because my dad is a minister, so I have a lot of repression issues that I was breaking out of. Also, sex is kind of interesting. [Laughs] There’s a reason why people are fascinated by it. There’s the psychological aspect and the physical aspect. But I pull a lot more punches now than I did then. I think that’s partially because it’s been stated already and I don’t need to go over that again. At the same time, because of the way I draw where it’s not realistic, for me, it’s not depictions of me having sex. It’s an abstraction. These characters are having sex at this point and it’s no longer so much like real people.

Is that the case for when you’re writing in general or is it more those specific scenes?

BROWN: It’s generally. For me to be as open as I am, there has to be that. There’s a disconnect for me in writing these books. It gets back to wanting to write about these stories from a different perspective, something a little more outside of myself. There are different levels to that: There’s the way that I draw the characters and the parts of the stories that I’m not putting in the books–all of that feeds into being able to have the characters and stories become their own self-contained thing. They come out of real life, but over time, being in the books, they become something else. It’s only showing parts and particular sides of things. Even though I try to write objectively, it’s obviously still my perspective in all of these books, and you’re only seeing certain events and certain things with the characters. There’s a lot more to everyone than that. That’s another way in which it’s a little less real.

How have people handled being the other half of these scenes?

BROWN: I mean, they handle it in various ways. [Laughs] Some people I don’t know because we’re not in touch anymore. I tend to have imagined what they might’ve felt about it. I try to be somewhat fair. I’m not pulling punches, but at the same time I’m not out to assassinate anyone’s character. I could certainly make everyone look worse or better than I do and still be true to the events; hopefully the people in the books recognize that. In a weird way, although the books are extremely personal, writing them doesn’t mean anything personal towards anyone else except myself. It’s not about who these people are, it’s about how I feel about these events.

So none of these are poison-pen letters or paeans to the one that got away or whatever–it’s more focused on your own reactions to what happened?

BROWN: Yeah, and not necessarily even me trying to get over something, but I’m interested in…you have this breakup and you have these feelings of sadness mixed with these memories of good things. There’s these bad things that happened, but you might start to idealize things. I’m just interested in exploring those feelings. It’s not that I use this specific person that I feel a particular way about to write about. I’m interested in trying to capture the feelings that I had at the time. That’s what I’m trying to get at.

Your life has changed substantially in the last year or so. You’re a family man now. You have a baby. How is that affecting you as a writer and as an artist, or is it at all?

BROWN: It’s definitely affecting me, even aside from the practical effects of time, figuring out when to get work done when you have this little person who’s totally dependent. For one thing, I see myself writing less autobiography about what’s happening now. Having a baby, you don’t really have time to process and think about things a lot. Maybe years down the road that’ll change and I’ll start to think about how I could write about having a family–I’ve written one story that touches a little bit on becoming a father–but right now I’m so much in the thick of it I can’t even imagine writing about that very much. It does change your perspective on life quite a bit, about what’s significant and what’s not. There’s this change to it where, I don’t know, you start to feel a lot older all of a sudden, and not necessarily wiser. You feel like a lot of the things that meant a lot to you suddenly mean a lot less. It’s hard to say exactly how it affects me, but the autobiographical work that I’m planning on doing is pretty dated, for the near future. I also think that maybe [I’ll try] to explore autobiography in a more safe form down the road, where I might tell stories from life but then try to find a way to set up more internal thoughts than I have in the past.

The industry has also changed. Your books do very well, you have famous fans like Michel Gondry and Death Cab for Cutie…I would imagine that since you started doing comics, the opportunities that are available to someone who does the kind of work that you do have exploded exponentially.

BROWN: Yeah, definitely. People are able to do serious comics and make more money from it. It’s not that people would go into comics just to make money, but if you’re a creative person…when you’re at a formative point where you’re thinking, “I’d like to make film” or “I’d like to draw comics” or “I’d like to write books,” it’s hard to make comics when you’re not making money from them because you’ve got to do something else to make the money, whereas if you decide to go into film there is a bigger opportunity to get to that point where you could make money from making the film. Now that’s something that comics has come into, where you can actually start to make money from doing it. That enables you to do more of it. The more people that are able to do that, and the more the outside media takes notice and you have publishers that realize there’s a market for these comics, it all feeds into itself and grows exponentially.

Do you still have a day job or are you doing comics full time?

BROWN: Up until a few weeks ago I was still working part time [at a bookstore], mostly to keep the health insurance, but my hours dropped down enough where I lost my health insurance. I still work one day a week because I really like books, and working at a bookstore is nice in some ways, but my income is basically all coming from the books that I have out and books that are coming out, and the occasional odd job here and there. I don’t really do any illustration work, but the things like the Death Cab video [I directed, for the song “Your Heart Is an Empty Room”] come up once in a while where it’s a little extra money.

What do you have coming out next? You mentioned the collection of autobiographical stuff and the high school/college/art school memoir…

BROWN: The collection is called Little Things. That’s due to come out next April from Touchstone, which is an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Then I’m still just in the scripting phase, but the other book is called Funny Misshapen Body. That would tentatively be scheduled to come out sometime the year after that, so 2009. Those are the two big projects that I’ll be working on for the next long while. At the same time I’m going to start doing a series of pamphlet comics with Top Shelf called Sulk. That’s going to be, again, my method of balancing out the so-called serious autobiography with the more humorous and free-flowing work. I’m going to do an issue with more Bighead stuff and an issue with 1 or 2 pages of funny autobiographical stuff, and there’s some other parodies that I want to do. That’ll maybe be 3 or 4 issues a year. It’s an idea that I’ve been kicking around for a while, and I’ve really started to figure out how it would work. I’ve actually got the first 8 or 9 issues scripted out, so it’s just a question of when I start to draw them.

Over the last year or two there have been a lot more actual alternative comics coming out, between the Ignatz and things like Uptight and Big Questions and Skyscrapers of the Midwest. It’s nice to see those things coming out from publishers again.

BROWN: Yeah. If you think about it, novels used to be serialized in magazines a lot. It’s kind of strange how the book market has become more profitable for comics. People have started to think, “Why do a pamphlet comic when I could just wait and do a book and have it on sale in both bookstores and comic book stores?” The nice thing about pamphlet comics is that for people who aren’t familiar with your work, it’s nice to have that little introduction. The Sulk series will be a place to put these shorter works that don’t necessarily have enough to them to fill up a whole book. I’m going to try to start [releasing] the series towards the end of this year, but that depends on getting it done. What I did wrong is that I started this one issue of Sulk where there’s 96 pages instead of 32 pages because it’s an Ultimate Fighting Championship one where there’s an 80-page fight scene. I started drawing that one first, so now I don’t want to put it down and come back to it. I feel the need to finish this one first, but I don’t plan on publishing it as my first issue. It’s kind of silly for me to draw it. Maybe I will put it down and just start Sulk. That makes sense. So November or December would probably be the next thing.

Finally, there’s The Incredible Change-Bots. I take it you’re a big Transformers fan?

BROWN: Yeah. I would get home from school and watch the cartoons, or on Saturday mornings when they were on. I had all of the toys and I read the comics. Transformers and G.I. Joe and Star Wars were the big toys for me. I haven’t done any comics for G.I. Joe or Star Wars yet, but there’s something fun about the idea of robots. I realized that I had ideas about things that are funny about Transformers that I could stick into a more extended thing.

So will we be seeing the G.I. Joe equivalent of Change-Bots from you at some point?

BROWN: I don’t know. The danger there might be that it’d be easy to get drawn into the politics and the real-world relations of things. It’s possible, but we’ll have to see if something inspires me down the road.

I write for “Twisted ToyFare Theater,” and I always amaze myself with the sheer volume of Golobulus and Dr. Mindbender gags I can come up with anytime we do a G.I. Joe strip.

BROWN: That’s great. In the McSweeny’s humor collection, there’s “The Journal of a Cobra Recruit.” He just talks about things like, “Today we ran forward holding a gun and screaming ‘Cobra!'” It’s really hilarious. It’s in the book that Charles Burns drew the cover for. You should definitely check that out. It’s so funny that I think it might make doing a G.I. Joe comic irrelevant.

I liked this interview.

Bookmarks

Remmrit.com user has just tagged your post as !