Posts Tagged ‘the giving of the rules’

183. The Third Rule, Verse 6

July 2, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, for the final time, is the third.

3. Be nice (concluded)

Previously:

- The Great Commandment

- The Parable of Someone Getting in Your Face and Calling You a Cocksucker

- Walking the Dalton Path Together

- It’s a Job / It’s Nothing Personal

- Two Nouns Combined to Elicit a Prescribed Response

As our lessons have shown us, there is nothing simple about the simplest of the Three Simple Rules. Be nice: Those two words pack a world of meaning into their duosyllabic totality. Through parable and paradox and painstaking explication of every detail, Dalton slowly indoctrinates his disciples in the six letters (plus a space) that are the true determinant of the Dalton Path’s meandering course.

Naturally, the Dalton Path must include its own Path-annihilating destination.

3 (Revised). Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.

That’s what Dalton wants. He says so. “I want you to be nice…until it’s time to not be nice,” he says, in so many words. This is the second time he’s given voice to his own desires when delineating the Third Rule, the other being “I want you to remember that it’s a job—it’s nothing personal.” We can hereby conclude first that nature of the work as work, as labor, is of central importance. Indeed we will see how this conception of the job allows Dalton both to assert that, as a laborer, he is entitled to all he creates, and how it gives him the detachment necessary to see himself (his self) as separate from the job that his self performs.

But it’s the second half that clues us in here. We recall that in saying “It’s nothing personal,” Dalton was employing the old “If you think this sentence is confusing, then change one pig” technique: He waltzed into these people’s place of business, fired several of them, told them his authority is absolute, noted what a bad job they’ve been doing, personally insulted them—sometimes via parable, sometimes via insinuation, always indirectly so as to stymie their righteousness in lashing back. If they managed not to take what he was doing personally, then they already will have understood the importance of not taking things personally.

Which brings us back to “Be nice…until it’s time to not be nice.”

“Well, uh, how are we supposed to know when that is?” asks Younger, the quietest of Dalton’s new believers.

“You won’t,” Dalton says. “I’ll let you know. You are the bouncers. I am the cooler. All I want you to do is watch my back—and each other’s…Take out the trash.”

We already know that the Dalton Path is a path we walk together. Here, at the end of the path, the point at which the Third Rule gives way to its opposite, where thesis becomes antithesis, where being nice becomes not being nice, is where we receive the most emphatic declaration of our collectivity.

It is not for us to know when the time to not be nice has come. We are but bouncers, seeing through a pint glass darkly. Dalton, the Cooler, will instruct us. And yet the cooler cannot be the cooler without his bouncers. He needs us to watch his back—and each other’s—just as much as we need him to tell us the day and the hour of the not-niceness.

This is all part of the same thought-flow, each point indistinguishable from the last. Without bouncers, the cooler cannot cool; without the cooler, the bouncers cannot bounce. Ad infinitum, world without end, amen.

And what are the Three Simple Rules, if not the cooler distilled to his intellectual essence, the flesh made Word? Time and time again we have seen how when released into a mind willing to receive them, they act independently, engendering the understanding required to understand them as they take their course. Each rule is Dalton made miniature, released into the Double Deuce of the mind, taking out the trash. And within ourselves, we have watched his back all along.

We will not know when the time has come to not be nice. We won’t need to. Dalton will tell us. He already has.

This marks the midpoint of Pain Don’t Hurt. Thank you for reading.

130. The Third Rule, Verse 5

May 10, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, for the sixth time, is the third.

3. Be nice (continued)

Previously:

- The Great Commandment

- The Parable of Someone Getting in Your Face and Calling You a Cocksucker

- Walking the Dalton Path Together

- It’s a Job / It’s Nothing Personal

Whenever two or more nouns are gathered to call a name, there is hate.This is the difficulty—well, one of the difficulties, in addition to being barred from coming within 200 yards of Jasper High—facing Steve the Horny Bouncer. He has heard Dalton’s commandment. He has heard the parable of someone getting in your face and calling you a cocksucker. He’s heard about the power of community, the innate dignity of the laborer, and the fact that it, whatever it is, is nothing personal. He simply isn’t buying it.

“Uh-huh,” he says, the sarcasm dripping from his lips in sufficient quantity to stain his shirt, were he wearing one. “Being called a cocksucker isn’t personal?” Gyp Rosetti, you have a friend in Steve.

“No,” says Dalton coolly and confidently. (Considering the degree to which men routinely sexualize their antagonism toward him, I’d say this is a man who’s been called a cocksucker many, many times.) “It’s two nouns combined to elicit a prescribed response.”

Well goddamn, looks like he was a linguistics minor in NYU! Thanks there, Chomsky!

Of course, he’s right. One need look no further than the fact that this is my 130th essay about a movie called Road House in 130 days to see that combining two nouns in the right way can elicit one hell of a prescribed response. I have chosen to give myself over to that response, but that’s just it: I made a choice. Dalton is attempting to convince the skeptical Steve that he has a choice too, and he can choose to let that shit slide.

Steve, you will not be surprised to learn, is not buying it. However, while dumb, he is no dummy. He senses he will not be able to best Dalton in the squared circle of neurolinguistic programming. Better for him to take a new and even more direct approach:

“What if somebody calls my mama a whore?”

Actor Gary Hudson’s delivery of the word “whore” is remarkable, a cousin in its way to Joe Pantoliano as Ralph Cifaretto, exasperatedly insisting “She was a hooah.” He takes the word and purses his lips and shoots it out the side of his mouth, like he’s trying to send it scurrying out of the servant’s entrance before the Duchess arrives. Nervous laughter erupts. All that his smug look of triumph afterwards lacks is the voice of Ra’s al Ghul from Batman: The Animated Series saying “Checkmate, Detective” or some shit.

Which leaves him wide open for Dalton’s riposte:

“Is she?”

Nervous laughter bubbles up again, at Steve’s expense this time. His smile sours. He takes the napkin or whatever he’s been tearing up OCD-style and tosses the latest shred to the ground in a rage. Anything he says would imply acceptance of Dalton’s framework, that rather than being some outlandish insult, the notion that Steve’s mother is a sex worker is a matter of some debate. Not since Dalton told Morgan “opinions vary” has he so thoroughly shut someone down.

Note that Dalton himself is agnostic on the issue. I’m not claiming any kind of “sex work is work” points for Dalton; this was an era in which even an NYU philosophy major may not have encountered this kind of thinking, and moreover his attitude toward Denise after her topless dance smacks of SWERFiness. And yet one is reminded, is not one, of Matthew 26:63-64: “And the high priest answered and said unto him, I adjure thee by the living God, that thou tell us whether thou be the Christ, the Son of God. Jesus saith unto him, Thou hast said.” Tou-fuckin-ché, Caiaphas.

And so it us unto you, Horny Steve. You have just given Dalton the rope to hang you with, rhetorically. When you diss Dalton, you diss yourself, and in so doing you yourself have set up the perfect demonstration of the wisdom of “Be nice.” Did Dalton say anything insulting? You’ll notice he did not! He left it to his foe to be his own undoing. Petard, here be thy hoist.

129. The Third Rule, Verse 4 Revisited

May 9, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, for the fifth time, is the third.

3. Be nice (continued)

Previously:

- The Great Commandment

- The Parable of Someone Getting in Your Face and Calling You a Cocksucker

- Walking the Dalton Path Together

- It’s Nothing Personal

But there’s more to Verse 4, isn’t there? Dalton doesn’t merely tell his acolytes that bouncing is nothing personal. He chooses to emphasize that bouncing is a job. Bouncing is work. Bouncing is labor. Through this lens, perhaps, we can arrive at the cod Marxism for which Road House has been crying out for years.

We’ve discussed one interpretation of the latter portion of this verse already—the need to maintain a level head, a distanced perspective, the ability to distinguish between professional challenges to be surmounted and personalized challenges to be destroyed.

At this point Dalton could, and indeed at a subsequent point he will, emphasize the “sticks and stones may break my bones” element. He could, and will, insist that though they will be dealing with physically and verbally aggressive patrons, those patrons have no insight into the men bouncing them and thus their words and deeds carry no true weight. That’s one interpretation of “it’s nothing personal,” and it’s valid.

But what does Dalton mean by counterposing “it’s nothing personal” with “it’s a job”? By situating bouncing within the context of labor and setting this up in opposition to the personal, he is underlining—and not for the first time—the communal nature of the task. The bourgeois conception of personhood, atomic individualism, false individual consciousness, Thatcher proclaiming “there is no such thing as society”: These have no place Dalton’s philosophy. When you do a job you do so in concert with your fellow workers, and, ideally, for the benefit of workers as a class.

You are no Morgan, searching for opportunities in which to vent your rage and exercise power at the expensive of the collective.

You are no Pat, enriching yourself at your fellows’ expense.

You are no Steve, fucking young women of uncertain age in the breakroom, or Judy, selling cocaine in the bathroom, indulging in hedonistic pursuits while others shoulder your burden.

“You are the bouncers,” Dalton says at the end of the Giving of the Rules. You are the proletariat. Through your labor the value of the Double Deuce is derived, a fact which is made plainer and plainer as the film goes on.

“I am the cooler.” Dalton is the vanguard. He seizes power with the intent of awakening the wider class of bouncers to their revolutionary potential and diffusing that power among them, and unlike other vanguardist movements he does so.

“Watch my back and each other’s.” Solidarity forever.

“Take out the trash.” Up against the wall, motherfuckers.

069. The Third Rule, Verse 3

March 10, 2019“This is the new Double Deuce,” says Frank Tilghman. We are at the start of an all-hands staff meeting, and Tilghman is pointing to the concept art for the bar’s redesign. But standing nearby is his latest hire, Dalton. It is through Dalton, with Dalton, in Dalton that the new Double Deuce will be achieved. Dalton embodies the new Double Deuce. He is its future.

When Dalton takes over as cooler he becomes more than just the chief bouncer. His role is not to handle a series of discrete incidents, but to institute sweeping reforms that will eliminate such incidents forever. “It’s going to change,” he states—not a threat, not a promise, a fact. His bouncers, too, must change for this to take place. As below, so above.

Bouncing on the Dalton Path is a matter of following “three simple rules.”

This, once more, is the third.

3. Be nice. (continued)

We’ve established the Third Rule’s Great Commandment, and we’ve examined its combination of theory and praxis. Today’s lesson follows closely in the latter’s footsteps. Almost literally, insofar as it’s about walking.

You’ll recall that the previous lesson introduced the parable of the man who gets in your face and calls you a cocksucker. In the lines that follow, Dalton continues the story. “Ask him to walk,” he advises his bouncers regarding such a person, “but be nice. If he won’t walk, walk him, but be nice. If you can’t walk him, one of the others will help you, and you’ll both be nice.”

By now his voice is pleasant, almost cheerful, the “it’s my way or the highway” edge to it long gone. It stands to reason, since the whole point of this passage is that neither he nor anyone else need walk his way alone. You can do so side by side, arm in arm, perhaps even hand in hand. Indeed his delicate double-handed gesture when he says “and you’ll both be nice” suggests nothing so much as a pair of children playing “Heart and Soul” together on the piano in the school music room.

This is the least difficult portion of the rules so far from which to glean the hidden moral instruction beneath the practical element. By way of comparison, eep in mind that “turn the other cheek” was as literal as it gets, at least within the context of the sentence in which Jesus introduced the concept: You get socked in the side of the face, you offer up the other side too. Yet hundreds of millions of people over thousands of years had no trouble figuring out what he was getting at.

I’d like to think that Jack, Hank, and Younger understand that Dalton is talking about more than just the problem introduced by Hank at the start of the Giving of the Rules: “A lot of the guys who come in here, we can’t handle one-on-one, even two-on-one.” Aiding a fellow bouncer in the ejection of a particularly recalcitrant or powerful patron is important. Even reiterating that the purpose of bouncing is to bounce the patron out of the bar, not bounce his head off of it, is important. But is “If he won’t walk, walk him,” so far removed from “it was then that I carried you”? Is “one of the others will help you” so different from “For where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them”? Seeing yourself as part of a whole that includes the patrons, the bouncers, and the bar—that is the key that unlocks the new Double Deuce, the nice Double Deuce, a house with many mansions. When you walk through the storm, hold your head up high, and don’t be afraid of the dark.

059. Men in Black

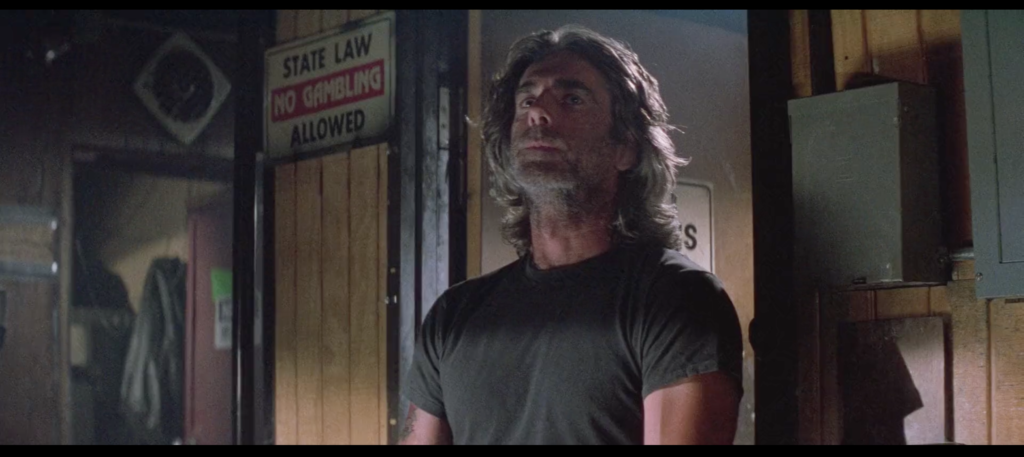

February 28, 2019When I wrote about Wade Garrett yesterday, I remembered something about his black t-shirt: He’s not the only cooler in the movie to wear one. The other of course is Dalton—but it’s not like he wears it all the time. The movie shows us he’s molded in Wade’s by deploying black in his wardrobe on three key occasions.

Attentive readers of Pain Don’t Hurt will have guessed the first by now: The Giving of the Rules. This takes place prior to Wade’s introduction, directly linking the older man’s debut to the establishment of his acolyte’s doctrine.

The second is the fight that takes place the night he and Doc have their first date, which is also the first time we see him on the job after we meet Wade. This reinforces the sense of succession while also tying Dalton’s romantic flourishing to the older man’s tutelage.

The third is his impromptu breakfast summit with Brad Wesley, during which Wesley brings up his checkered past and offers to hire him away from the Double Deuce. It’s not a t-shirt here but a collared shirt, as befits this more formal occasion. But the dialogue makes direct reference to an event in Dalton’s past that Wade will also bring up (while wearing a collared black shirt himself) later in the movie, and shows Dalton standing up to an asshole in a way that would do his mentor proud—even if he’d likely suggest getting out of Dodge afterwards.

Clothes make the man. Clothes mate the men.