Posts Tagged ‘The Dark Is Rising’

Vorpalizer

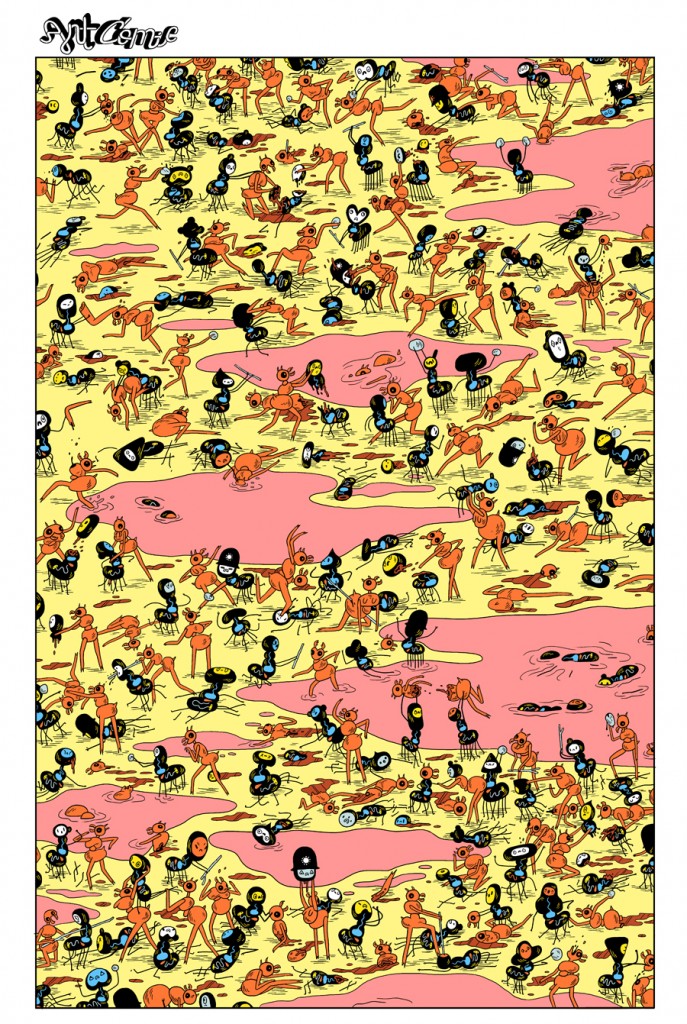

February 6, 2013I’m going to be writing about science fiction, fantasy, horror etc. with some dayjob coworkers at our new group blog Vorpalizer.com. I got started with posts on Michael DeForge’s Ant Comic and Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising. Come check it out.

Book reports

February 4, 2011One of my favorite things to do (and what this says about me I couldn’t begin to guess) is backlog enough comics reviews that I can take a few weeks off from the funnybook grind and plow my way through a suitably ambitious prose-reading project. This winter that project is apparently reading fantastic-fiction series written for young adults. First up was Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising Sequence, which I’ve talked about a bit before. Christmas almost always puts me in the mood for these books, just like seeing bugs congregate around my houselights when I take the garbage out at night makes me want to re-read Stephen King’s “The Mist” every summer. The Dark Is Rising, which gave the series its name, contains some marvelously Christmasy stand-offs between good and evil in the English countryside, involving carols like “Good King Wenceslas,” constant references to Midwinter’s Day, the magical properties of holly, and so forth — the ancient Britannipagan roots of the Christmas traditions we know today. But it’s also the second book in the series; the first, Over Sea, Under Stone, was written some years before the rest and is much more a children’s mystery and much less an overt fantasy. So you kind of have to buckle down and commit to reading the whole megillah before you get to the candles and wassails and mince pies and so forth (whereas with “The Mist,” you get a sweltering summer instantly and giant insects crawling across supermarket windows within half an hour’s reading), which is an investment. But this year I felt up to the challenge, and thus over the holiday break I took a crack at the whole series for the first time in eight or nine years. I ended up quite impressed by how much mileage Cooper could get out of merely describing how her conflict between the Lords of Light and Dark — and I mean sheer description, an endless succession of infodumps. Any time our young chosen-one hero Will confronts the enemy, the rules governing their conflict are simply asserted, either by the more experienced characters or, after he reads a book that literally teaches him everything ever, by Will himself, rather than uncovered through action. It’s not a choice I’d have made, certainly…and yet it never feels lazy, somehow. Why? Because Cooper’s overriding theme is that pure Light and pure Dark are both hard masters. Having all the usual fantasy story beats arrived at not through struggle or coincidence but by through “it is the way it is, the way it must be” rules and prophecies and plans and destinies makes perfect sense in a world where even the heroes are resigned to the occasional destruction of the souls of normal humans with the misfortune to be caught up in the conflict. Don’t get me wrong, this series isn’t at all about the necessity for Hard Men In A Dangerous World; indeed I’m not sure there’s any appropriate ideological/allegorical reading to be applied to it. It’s more a combination of Cooper pursuing the brand of fantasy that most intrigued her — lofty and explicitly Arthurian — and then occasionally, and particularly in the masterful Newbery Medal-winning fourth volume The Grey King, chronicling the emotional effect such cold purity has on we hot, impure humans. It’s a fantasy series with a lot of images that shine brightly — the Black Rider, the White Rider, the Six Signs, the Afanc, the Mari Lwyd — but also sting.

Far closer to ground level is Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain Chronicles. Like Cooper, Alexander drew heavily on Welsh legends, but that’s pretty much where the similarities end. On the surface it’s the most (and prior to A Song of Ice and Fire, the only) thoroughly Tolkien-indebted fantasy series I’ve ever read, albeit one written on the reading level of The Hobbit throughout its five proper installments and subsequent collection of prequel short stories. There’s a dark lord (Arawn, Lord of Death) who rules a stronghold at the edge of the known world (Annuvin) and sends his undead thralls (the Cauldron-Born) against a motley crew of various beings (the Companions) masterminded by a wizened wizard (Dallben) and spearheaded by an unlikely-hero hick (Taran, the Assistant Pig-Keeper) and his scion-of-royalty guide (Prince Gwydion of the Sons of Don) whose home is eventually besieged (Caer Dathyl). Where Alexander distinguishes himself from the good Professor is in the welcome regularity with which he drives home the central theme of the book: “Please put in the hard work necessary to learn how to not be a jerk.” He depicts Taran’s intellectual, emotional, and ethical growth process in such detail that it’s almost an instructional volume. Taran is never swept along by the mystical conflict with which he becomes entangled on his way to becoming a hero — he trudges and marches and stumbles and picks himself back up and continues to trudge through it. In each book Taran repeatedly is faced with decisions only he can make; he makes them first impetuously, and after learning how that usually works out, with as much care and consideration as he can muster; they either work out or don’t; then — crucially — he accepts responsibility for the results of the decision, accepts the results themselves as the terrain on which he must operate, and endeavors to move forward from there. It’s a constant process of experimentation, failure, contrition, and moving forward with his friends’ support. People try to do right by each other in this book, at all costs. One sacrifice, toward the very end of the book, made me tear up, something I thought I was long past in books like these — it wasn’t even a fatal sacrifice, just one you knew tore the sacrificer’s heart out but didn’t stop him from making it to help the people he cared about. He’d learned not to be a jerk.

I tweeted about all this a few days ago, and two separate people tweeted back in virtually identical terms that the books sound like the anti-Ayn Rand. That’s precisely it. The message is that acting responsibly toward others is really the only way we can gauge responsibility to ourselves — an enormously salutary message, more so now even than when the books were first written over four decades ago. Indeed Arawn Death-Lord’s greatest evil is said to be not his warring and general sorcerous nastiness, but his theft of the skills and secrets that made everyone in Prydain’s lives better once upon a time — better ways to farm and build and sew and create. Arawn took them all and hid them in his own private Galt’s Gulch; Taran’s quest was in part to liberate them, but much more than that it was to work to find his own gifts, and his own limitations, and contribute to the lives of others as best he could.

(In that light it’s hard to find fault with Alexander for his one weakness here, which is that he’s far more willing to harm the characters his main characters care about than he is to harm those main characters, i.e. the ones he and we care about. (This made me appreciate just how much of a taboo George R.R. Martin really shattered, by the way.) Plus, Arawn, the Cauldron-Born, the Huntsmen, and the Horned King are all world-class villains, so on a fantasy-mechanics level there’s still plenty to crow about.)

Finally I’ve just now started Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games. I don’t know what I was expecting, prose-wise, but it certainly has that slightly-weak-YA-fiction tendency to eliminate subtext and spell everything out. If the heroine has a tragic backstory, she is going to tell you what it is in the opening chapters. If she feels one thing but is forced to say another, she’s going to describe the situation to you in pretty much exactly those terms. In other words, big surprise, the writing is not as strong as George Orwell or William Golding. Don’t go comparing dystopian apples to oranges as I did.

What it has going for it instead is two things, as best I can tell. I only got up to the actual Hunger Games — the Battle Royale-style bread-and-circuses spectacle in which tweens/teenagers from the subjugated populations are forced to fight each other to the death for the sport of the ruling class as a way to show everyone who’s boss every year — today, but obviously as with any such dystopian-future bloodsport set-up, the kill-or-be-killed nature of the Games is pure narrative napalm. You’ve got a built-in structure that keeps people turning the pages, you’ve got a ready-made cast of varying antagonists you can endow with noteworthy quirks, of course you’ve got life or death stakes, and you have the audience’s expectations that at some point your hero (or heroine, in the case of lead character Katniss) will rip the lid off the system and show the world that the game is rigged and the only way to win is not to play. Juicy, pulpy stuff, regardless of how many school summer reading lists it’s on.

The other thing (and again, I’m barely halfway through volume one, so who knows where if anywhere this all leads) is that it makes bracingly literal contemporary culture’s penchant for watching young people display themselves and/or die for our entertainment pleasure. There’s an out-of-nowhere injection of kink before the games begin — Katniss is stripped, shaved, inspected, and tarted up by a team of stylists to help her win over the crowds; she has every expectation that she may be made to perform in front of a live audience of thousands and television audience of millions stark naked, which has apparently happened to the teen contestants in the past — that fairly blew my mind at age 32; if I’d read this when I was part of the target audience I’m not sure if I’d ever think of anything else. That willingness to go there in the face of what I imagine were objections from the folks in charge of placing this thing in libraries was refreshing.

Moreover, the youth of the bloodsport contestants, as mandated by the government, reminds me not just of the simultaneously voyeuristic and condemnatory coverage of teen misbehavior upon which huge swathes of the media depend, but also of the cold hard fact that when wars are called for, what’s really being called for is for young people to travel someplace to kill people and get killed. Again, I’d imagine that if I were a teenager, this would connect with me very hard on some level, even if I weren’t able to quite articulate how.

On a sillier note, I can’t remember the last time I read a book that my mind cast with actors as quickly and irrevocably as it did here. Katniss is Kristen Stewart, skin tone be damned; Gale is Talyor Lautner; Peeta is Armie Hammer minus a few years; Effie is birther queen Orly Taitz with the voice of that “great, great, really great!” woman from Elaine’s office in Seinfeld; Haymitch is Lieutenant Eckhardt from Tim Burton’s Batman; Cinna’s the guy who runs the New York City bridal salon on Say Yes to the Dress. I wonder who will be brutally murdered next.