Posts Tagged ‘The Comics Journal’

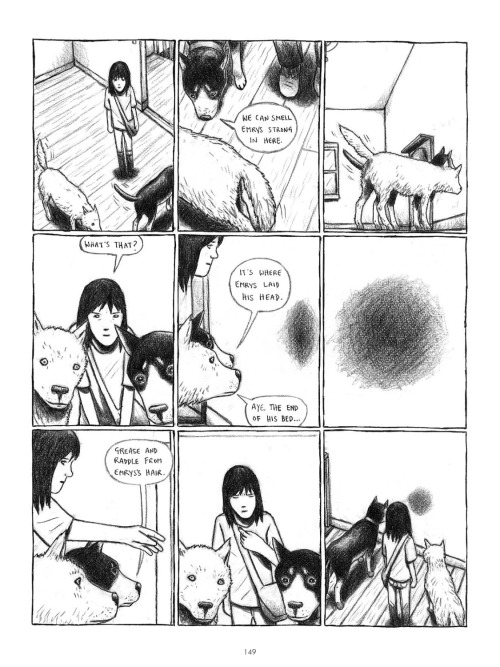

An interview with Julia Gfrörer: ‘I don’t think that I could make like a nice book if I wanted to’

May 30, 2025Are there any self-imposed taboos in your work, like rules that you won’t break?

Yes, there definitely are. Probably a lot of them are not things that I’m immediately conscious of. I won’t put a beautiful girl on the cover of my book, just because I find it boring and kind of pandering, and also obviously kind of misogynist. I guess I don’t really like to put people on the covers of my books at all.

I’m very careful about the way that I depict violence, domestic violence, sexual violence, things like that. I think it’s important to show, and I won’t hide them. There can be a tendency to think it’s fine to show these things as long as you do it properly in a way that it telegraphs your true intentions, so you have to have a disclaimer on every page that says, well, this character is stomping on a duckling, but I would never stomp on a duckling.

I try to show things like that with as little judgment as possible, because when you encounter those things in real life, they don’t usually come with a disclaimer. And usually when violence suddenly appears in your otherwise violence-free day-to-day life, it is difficult to know how you are supposed to feel about it. So I don’t want to give the reader any help in that regard.

I also won’t show things that I can’t stomach. So if there’s a certain type of violence that I show, like, for example, I don’t know if I’ve ever shown somebody being burned alive. I think probably not. But if I were to show that, I would do my best to read firsthand accounts of that type of death, people who have come close to it, people have witnessed it, or maybe even watch videos of it if they exist. I mean, to my way of thinking, it’s the least that I can do.

Like, to honor those who have been burned alive.

I guess it sounds kind of silly when you put it that way. I just don’t think that I have any right to use that as part of my story if I can’t face it. Does that make sense?

Well, you’re taking a lot of time to draw it, so that’s a sustained amount of time where you have to think about it.

Yeah, and that’s part of how I choose the things that I write about. I will purposely choose things that are difficult for me to think about. I really hate drawing close-ups of people screaming. I hate to look at them, but I do sometimes think they’re necessary. So I and make myself do it and I lean into the discomfort for my own sake to feel like I’ve earned it, maybe. It makes my entire process sound very masochistic. It’s like the comic is just a byproduct of my own need to just kind of swim around in the cesspit of human experience. That can’t be healthy.

And yet.

And yet. I mean, it’s more healthy than a lot of other ways that I could be chasing that feeling.

My brilliant friend Matthew Perpetua interviewed my brilliant wife Julia Gfrörer about her brilliant book World Within the World for the Comics Journal! If you’ve ever been curious about her stuff, this is the interview to read.

Memories of Tom Spurgeon

November 19, 2019I wrote about my friend Tom Spurgeon for the Comics Journal’s collection of eulogies. I miss him very much.

“‘Best’ Is a Bullshit Word”: Phoebe Gloeckner on Editing “The Best American Comics 2018″

January 1, 2019To get deep in the weeds a bit, when you’re selecting the best comics—

Okay, get rid of that word. Get rid of that word, because it’s not possible. OK, yeah, you’re choosing the “supposed best” or “so-called best comics,” right, yeah?

Mmhmm.

What is your responsibility to your readership? What do you think when you’re possessing them? Well, I don’t fucking know. [Collins laughs.] No, honestly! I’m not thinking I’m choosing the best because I know I am the filter. What matters to me is, Do I like it? Did I like it more than a number of other comics? If the answer is yes, maybe I’ll include it, because what else do I have?

It’s like grading student work, in that you’re looking for so many things. You’re looking for: Can they draw, can they write, is it working together? Then you think, Well, I’ve known this student for two years. Look at them two years ago and look at them now. God, they are so good, and they are so much better than they were. They’re really trying hard and they’re really actually finding out what they can do. They might not be your best student to someone looking in from the outside. But sometimes you get these students who are great coming in, but because they can draw so well they have no real way to push themselves. You can see that they’re stuck. Their stories are a little weaker. Any criticism you give them, they halfway don’t believe it, or get pissed because they know they’re good. And they are, but they get this attitude and they don’t really get better.

So on the outside you can say “That person deserves an A”—the person with all the talent—and the one who tries so hard and gets so much better and will continue to do so, from the outside you might think “That’s C work.” In reality, you’re looking at so many things that other people who might not be inside this classroom wouldn’t take into consideration.

It’s the same when you’re looking at all this work. Because we’re individuals, we tend to like certain things or be interested in certain things, not in others. You try hard to put that aside, but you can’t. You can’t get out of your own skin. In the end, you’re going to choose things you like for reasons you don’t even understand.

Are you asking me, Do I feel any responsibility towards the reader? Or if my role is, in a very dry and responsible sense, to present only the finest? I mean, what are you trying to ask?

Well, for example, a couple of years I was hired to write a piece on “The 33 Greatest Graphic Novels of All Time.” Immediately, I said to myself “This is going to be my list of the 33 greatest graphic novels of all time, not a survey of the major landmarks from each genre and tradition and geographical region. You can get that anywhere, but you can only get this from me.” How do you draw the distinction between the quote-unquote “best” and stuff that you, based on your own interests as a reader, as an artist, as a person, as a teacher, whatever, like the best?

This is different in that I wasn’t asked to choose my all-time best stories or favorite stories. It was just my favorites among those that were sent, submitted, or solicited at this particular period of time. In that sense, it is harder to impose your own tastes and preferences on the group. You didn’t direct yourself towards a certain group of comics, they’re just placed in front of you.

I went into it thinking—and Bill Kartalopoulos said—“It’s your favorite from this period.” He kept emphasizing, “You’re the one who’s choosing which ones will go in the book.” If we had been asked to honor the accepted greatest cartoonist or the best-selling up-and-comers, I mean, that would’ve been really different. Publicly that may have been more recognized as, this is good, this is bad, but it wasn’t like that at all. They always have a different guest editor because it’s understood that different tastes will be reflected depending on who’s judging the work.

Bill, in his foreword, says his task is different than the guest editors in that he’s seeing all the submissions and whittling them down to a broad range of suggestions, but one that’s still smaller than the overall submission group. As much as he stands by his personal taste and feels it’s informed and defensible, he puts it aside as he’s looking at work in genres or tones that he’s usually not interested in. He thinks to himself, Okay, well, this may not be my thing, but it’s a thing. Is it a really good example of that thing? Is it an ideal version of that thing? Is it doing something new with that thing?

Right, but he also admitted that he constantly chose things he thought I might like. I always thought, What exactly does that mean? I actually do like lots of things, so I wasn’t sure what he meant by that.

But with all those questions—is it doing something groundbreaking, is it really the best example of this type of thing in any particular year—even the most prolific artists aren’t vomiting up stuff at a fast clip relative to other forms of communication. What are the chances you’re actually going to get work that fulfills all those criteria? Sometimes, you’ll get really brilliant shining examples you can hold up and say No doubt, this is best, everyone will agree. Sometimes you’re getting a book that is better than others, but nevertheless this particular artist did a book that you liked far better two years ago. Yet you’re going to include this because it’s actually something you can say you admire more than you appreciated fifty other books that were also submitted. You’re not always going to get that many outstanding pieces of work, even from the best artist. If you look at a body of work you’re always going to have a preference for this period or this story or this book over another, even in one artist’s work. “Best” is a bullshit word. Nobody’s ever going to agree on it.

Comics Time: Worst Behavior

January 14, 2015How do you take something as complex and confounding as the most tumultuous time in a person’s adult life and make a concise and compelling short story out of it? Annie Mok’s solution: Echo the tumult. In as-below-so-above fashion, Worst Behavior, an illustrated memoir for the “Dedication”-themed January issue of the online magazine Rookie, utilizes a hybrid format to describe and analyze a three-year period during which a host of issues that by rights would be overwhelming individually pulled Mok’s life in a dizzying number of directions. She uses prose, comics, illustration, hand lettering, sampled/disassembled/reassembled passages from her previous work, and quotes from the artists who’ve inspired her along the way to harness that onslaught in an act of creative judo, simultaneously communicating its power and demonstrating her artistic, emotional, and intellectual ability to best it.

I reviewed Worst Behavior by Annie Mok for The Comics Journal.

Say Hello, Leah Wishnia!

December 19, 2014[LEAH WISHNIA:] I honestly don’t really think too much about how my own comic work fits into the over-arching canon of alternative comics and such. I’m just trying to do work that I enjoy and that others might appreciate as well. Although I like to think of my own comics style and vision as being unique, I don’t feel that it’s necessarily at odds with other alternative comics that are being produced and distributed right now—in fact, there’s quite a few contemporary cartoonists whose output of work I totally “get,” work that seems rooted in a similar place as my own.

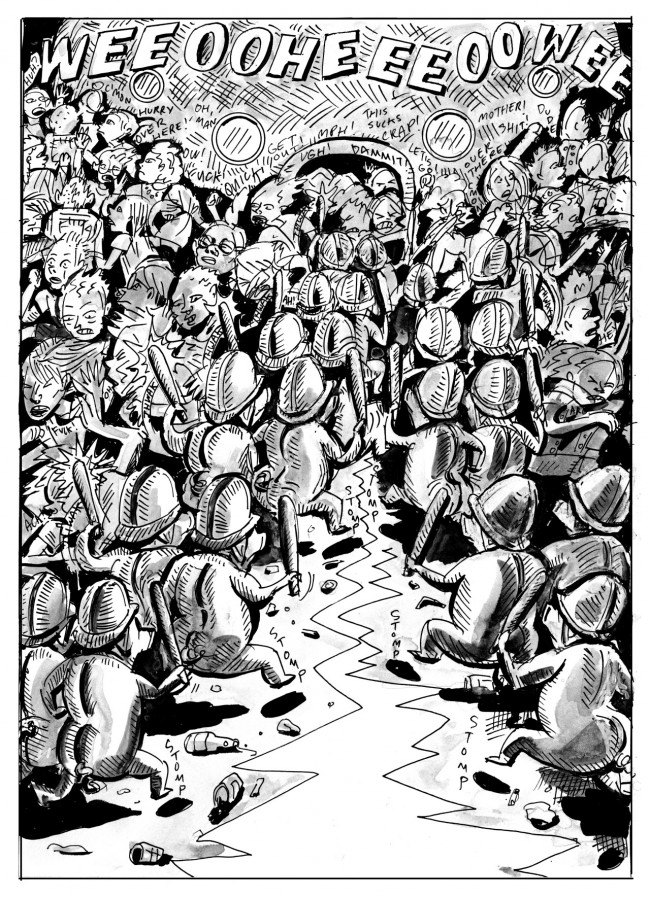

Indeed, though, many of my comics have featured characters that act and react quite dramatically, a kind of exaggeration of some negative attributes I see in both myself and in others. I think there’s a lot of chaos and pain and greed present in our culture right now that often goes unnoticed or unaddressed, so I like to take those negative things and amplify them until they reach absurd proportions, beating people over the head with it all until someone takes notice.

Comics Time: Earthling

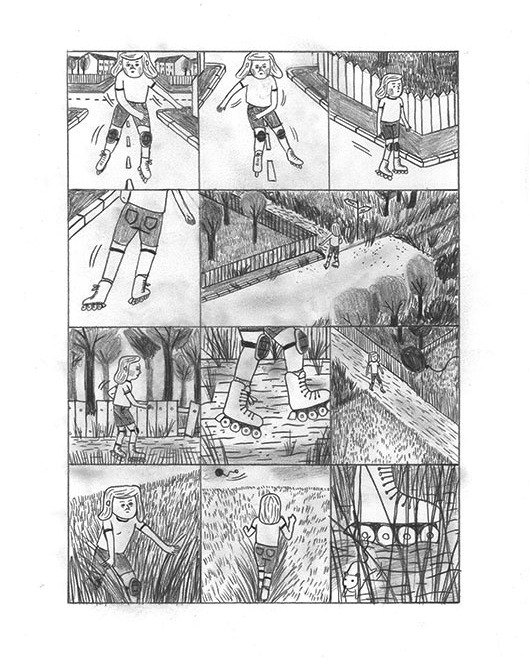

November 12, 2014Aisha Franz’s faces are an architectural marvel. Their features bunch up in the center of great round white circle heads crowned with hair that looks sculpted from clay. They’re bookended by apple cheeks drawn with a perpetual blush rendered as circular gray scribbles, as though a physical ordeal or an uncomfortable emotion were always only scant seconds in their past. Eyebrows, wrinkles, creases, and smile lines push the eye toward the beady eyes and pug noses they ring. (The look is very Cabbage Patch Kids, but there’s a reason those weird-looking things made millions.) They broadcast emotion from the center of the head like a spotlight focused down into a laser — curiosity and confusion, peevishness and puckishness, boredom and loneliness and anger and, very occasionally, satisfaction and delight. In a book where Franz’s all-pencil style — the lack of inks and the deliberately boxy and rudimentary props and backgrounds suggesting a casual, tossed-off approach completely belied by Franz’s obvious control of this aesthetic — works very well, those faces work best of all.

The story is another matter.Earthlingtells the not-quite-multigenerational tale of a suburban mother and her two daughters — one on the cusp of puberty, the other of college. The book derives its title from the storyline of the younger daughter, who encounters and attempts to befriend an alien visitor she hides in the toy chest in her room. But it’s equally concerned with her older sister, who’s negotiating the needs of an estranged best friend, a physically eager but emotionally aloof suitor, and an absent father whose scheduled return is impending; and with their mother, who alternately seeks to discipline and connect with them while pondering a turning point in her own past. None are happy; all deal with their unhappiness alone. That’s the only choice allowed them in the book’s closed emotional system. Franz casts every supporting character as mean, manipulative, or oblivious. She paints her protagonists with a similar palette, or at least portrays them as so fixated on their own difficulties that they are useless to one another. Thus the storytelling deck is stacked against each to such a degree that we are forced to come to the same conclusions they do: no one understands them, the situation is hopeless, and only rash renunciations of responsibility or intercession by a well-timed savior can liberate them. Perhaps inadvertently,Earthlingteases out the undercurrent of narcissism that those of us who suffer from depression often suspect, and fear, helps fuel those gray-pencil periods in our lives, but only to reinforce it.

Comics Time: The Basil Plant

November 12, 2014As an object, The Basil Plant is not much to look at. The same can’t be said of author Laura Lannes’s cartooning — as economical and as energetic as a well-delivered joke, with a thick, versatile line, and figurework that alternately recalls Anders Nilsen and Gabrielle Bell as played for laughs. The package containing that cartooning, however, is a bog-standard staple-bound minicomic, about 4.5″ x 3.5″, black and white, xeroxed, one page = one panel, its sole two-page spread not even located in the center of its 28 pages. You’ve seen a million of these things if you’ve been to a single small-press show. If you pick it up with the intention of reading it, you’re probably disinclined to be impressed. This is because you’re a sucker, which is what Lannes is counting on. The Basil Plant relies on your belief that you know what you’re in for. You think you know, but you have no idea.

I reviewed The Basil Plant by Laura Lannes for The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Gast

October 23, 2014Murder mysteries are defined by their central, structuring absences. A hole occupies the space where a life once lived. That hole can never be filled. But through an investigation of the facts, an uncovering of the truth, and a pursuit and capture of the killer, we can define and discover the shape of the hole to a degree of accuracy sufficient to put a cover on it, so that the still-living may proceed past it once more.

Gast, a graphic novel of exquisite and accomplished empathy and restraint by alternative-comics veteran Carol Swain, tells a story centered on a hole far harder to close up than most. It proceeds with the methods and mechanics of investigation and discovery. The scene of the crime is visited. The victim’s routine is examined. The friends and acquaintances of victim and suspect alike are questioned. Evidence is recovered and cataloged: a discarded make-up bag, a shell casing, a stain on the bedroom wall. Means, motive, and opportunity are all established.

But there is no crime, because killer and victim are one and the same. There is no pursuit, no arrest, no trial, no conviction, because there can’t be. We don’t so much as see the dead person once — not as a corpse, not in a flashback, not in a photograph. All we have is what is learned by a quiet, curious eleven-year-old girl, Helen, a lover of nature and long walks who must piece together even the most basic of facts about the deceased. At first we don’t even know the deceased is a person: Helen is simply told of a “rare bird” who killed himself nearby, and as a Londoner newly arrived in the rural region of Wales where the story is set and unfamiliar with the antiquated expression, she starts her search looking for an actual bird. Like the pages of the ever-present journals, Helen starts with a completely blank slate. Over the course of many long wordless walks and quiet conversations with both her human and, mysteriously, animal neighbors, she slowly fills the tabula rasa with discoveries: suicide, gender dysphoria, the allure and peril of solitude, and the life and death cycle of this farming community and its inhabitants. She learns that most adult of lessons: We each of us have roles we play in the lives of others, shapes we take in their worlds—shapes that can be integral to those lives’ landscape yet still not save us.

Comics Time: Honey #1

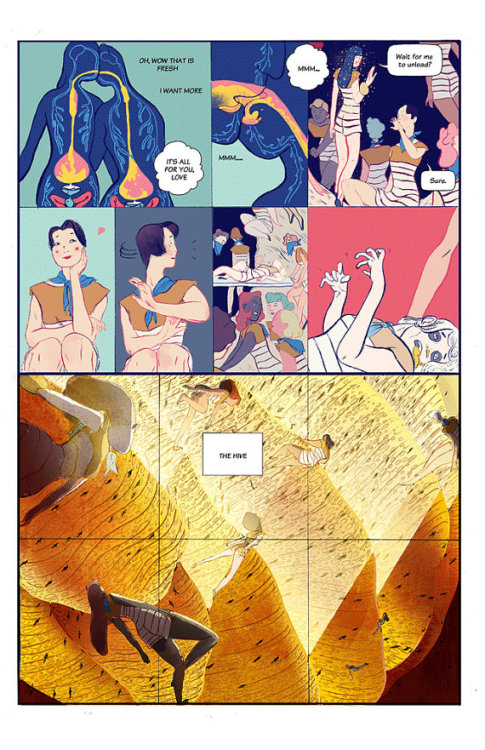

October 10, 2014Honey #1 is an elegantly drawn, exuberantly paced, spectacularly colored workplace dramedy/romance. It’s an action-adventure story set in a fantasy-indebted world with prominent horror elements. It’s a radical reconsideration of anthropomorphism and “funny animal” comics. It’s a serious exploration of how communities shore up certain strengths of the individuals they comprise while also pushing them all toward willful ignorance of wrongs committed in their name. It’s a gedankenexperiment about an all-woman society — imagining it, putting it through its genre-story paces, examining female friendship, romantic relationships, and enmity in the fresh air created by the near-total absence of men and thecompleteabsence of men in positions of power. It’s hugely, admirably, refreshingly ambitious for a twelve-page comic book. If the work cartoonist Céline Loup assembles from these myriad parts is not without flaw, that’s almost beside the point.

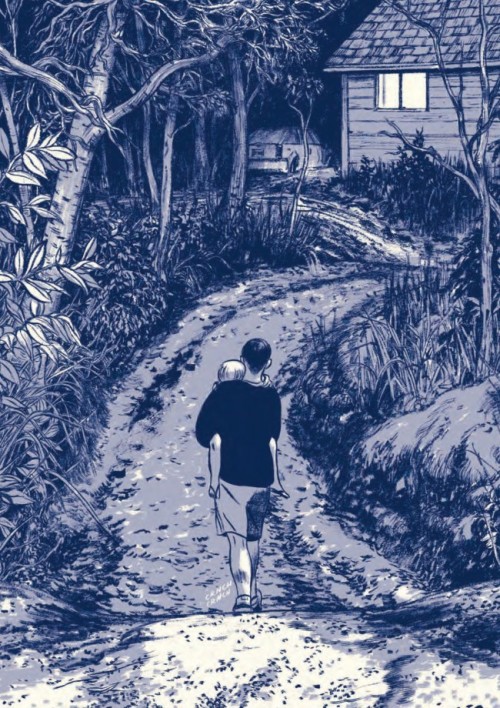

Comics Time: July Diary 2014

September 15, 2014At first glance, Gabrielle Bell’s six-panel daily diary comics don’t have a lot in common with the Mines of Moria sequence in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings . Or at any number of subsequent glances, I suppose. But the more Bell I read, the more I think they share a primary strength: a sense of space, of environment. Autobio slice-of-life comics, by the nature of what most of us tend to do with our lives every day, often consist in large part of conversations, either with a small number of other parties or within the head of the diarist as they go about their day. Unless those conversations reference a specific landmark, cartooned depictions of them can, and often do, devolve into dialogues that could be taking place anywhere, or nowhere. They have all the spatial context of action figures or dolls or sock puppets held aloft by the cartoonist, one in each hand, and made to speak with the voices of the participants.

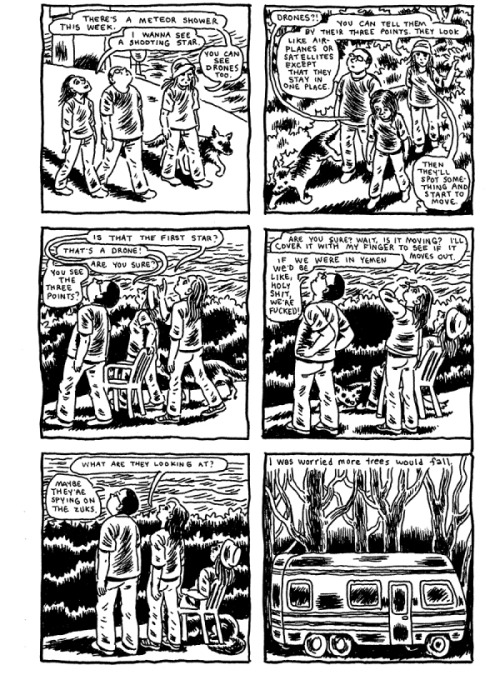

Not so with Bell, and not so in the most recent iteration of her annual July Diary project. Hers is a world where rooms, furniture, streets, buildings, and human bodies are arrayed in a three-quarter cheat to the audience, enabling us to see into corners, grasp the depth and dimensionality of each space. Her inimitable spotted blacks — little jagged-edged rectangular smudges — set off the surfaces of the objects with which she is surrounded, and pool in the wrinkles of her characters’ clothes like ink. It’s impossible to look at a Gabrielle Bell diary-comic page and reduce it to stick figures against a blank backdrop, any more than you could do so with the fellowship of the Ring dodging orc arrows as they flee down those crumbling steps. Her apartment, her garden, the streets of her neighborhood, the wilderness surrounding the trailer where her mother lives following the house fire that understandably dominates the diary — Bell makes them distinct, inhabitable, navigable spaces. That her rigid, six-panel grid closes those spaces off is a feature, not a bug. Each panel feels like a tiny, beautifully constructed diorama, where Bell and her acquaintances will act out the same moment forever.

I reviewed Gabrielle Bell’s July Diary 2014 for The Comics Journal.

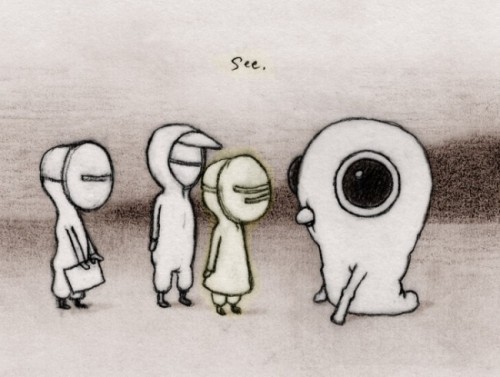

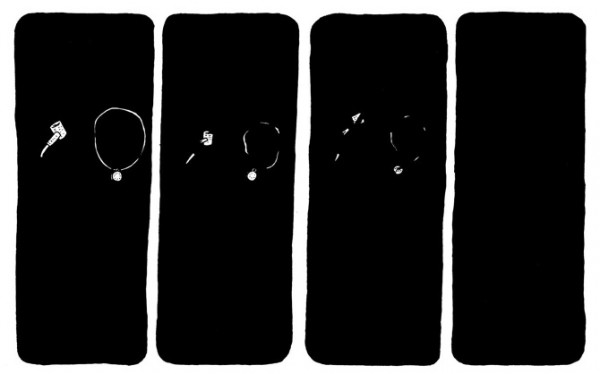

Comics Time: Baby Bjornstrand

September 3, 2014A thing comes into three lives, without warning or explanation. A thing leaves those lives in much the same way. The time between: Baby Bjornstrand, the new Renee French graphic novel completing and collecting the webcomic of the same name. In the past, I’ve written that the hazy, watery wasteland inhabited by Baby Bjornstrand‘s masked, hooded protagonists and monstrous fauna evokes a post-apocalypticism that is, if not belied, then at least transfigured by the comic tone of the proceedings. Now that the series is finished, that’s only true to a point. As the uniform proscenium staging of its panels suggests, Bjornstrand remains much closer to Samuel Beckett than Stephen King, despite French’s astonishing proficiency with painstakingly penciled menace. Yet its morose ending has a bite that doesn’t require the jaws of a monster.

I reviewed Baby Bjornstrand by Renee French for The Comics Journal.

Say Hello, Meghan Turbitt!

August 25, 2014I’m particularly interested in the idea advanced in Sophia Wiedeman’s piece on you and Katie Skelly for The Rumpus that your work is driven in part by Catholic guilt. Certainly your comics seem to revel in a rejection of Catholic mores, but more than that, they don’t smooth out the rough edges to make the violation more palatable, you know? The sex is, frankly, gross, and so is the food component, once that’s introduced in #foodporn.There’s not an attempt to play respectability politics with it.

Everything I make, every particle of my being, is based on how I grew up. Everything I make will of course be influenced by that. But to be honest, the reason I made #foodporn is because I had a crush on an ugly guy who made pizza at my local pizza joint. He is not attractive. When he was making the pizza I was attracted to him, though? I didn’t understand it and I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I thought the concept of him getting hotter and hotter as he made the pizza was just hilarious. Hence the premise of the book.

Oh, just an interesting piece of side trivia – I finally did end up having sex with him, two days after #foodporn was released at MoCCA. I’ve stopped eating pizza since.

Typically when comics creators talk about essentially willing something from one of their comics into existence, it’s, like, Grant Morrison talking about tripping in Nepal or whatever and discovering the true nature of space-time. This is somewhat more relatable. But if it put you off pizza, then I wonder if in retrospect you’d have preferred it to have remained a fantasy.

Very interesting to me that you use the word “fantasy.” In March, I got out of an eight-year relationship. We had broken up and I moved out in 2012, but we ended up getting back together very quickly. But over the last year I had several crushes on people, especially this pizza guy, and I ended up making the comic about him. Things were just not working out with my ex, even though I loved him very much and he was family to me. I spent a lot of time fantasizing about “what life would be like” with certain other people, and this pizza guy was first in line. However, I didn’t make any moves about ending the relationship for almost a year after making the comic about him. My therapist had a real woman-to-woman conversation with me, knocked some sense into me, and suggested to me that my life might actually be greater on the other side of ending things with my ex, so I did it. For some reason at that moment it hit me that my life might be better with my ex not in it, which seemed almost unfathomable to me. She was right. So I guess one could say, therapist Sean, that maybe I avoided one of those painful Irish-Catholic illnesses or avoidance-of-feelings situations here? Perhaps history did not repeat itself, hmmm?

Luckily, things with this pizza guy fell into place — I got drunk at the pizza place and propositioned him — and we saw each other for a little while. It certainly served a purpose and helped me get through my breakup. I suddenly felt sexy again. He knew about my comic about him, and about #foodporn. He was aware I was doing some podcast interviews and being reviewed, and the comic about him was mentioned a few times. One night, in the midst of all this, he told me that he had gone to my website and looked at my comics, and told me, “Wow, I thought you were going to be much more famous than just this.” He also referenced myConancomic, in which there is a long sex scene between me and Conan O’Brien, while we were having sex one night, which I thought was hysterical, and which I am currently making a comic about now.

Anyway, this pizza guy was into Phish, and if anyone knows me they know I’m not into jam bands, so it just wasn’t meant to be — even though I continued to draw him and make comics about him while we were seeing each other. I guess I was just looking for anyone who wasn’t my ex and was fascinated by that. A few months after we started seeing each other, my friend Holly caught him arm in arm with another chick around the corner from my house. She went into the pizza place, which we frequented regularly, the next day and called him out in front of all of his coworkers. Needless to say, we haven’t really been back there since. So my ultimate curse is that I live half a block away from a pizza place that I love and can’t go to. So fantasy, shame on me I guess. All around, it’s been a fascinating chain of events for me to witness go down. And now I’ll have #foodporn to document it for the rest of my life, so “LOL,” I guess.

Comics Time: Danny Boy

August 8, 2014…the ending is otherwise the strongest section of the comic, the one place where Danny Boy takes on a life of its own. It does so in death. In the end, father and son are buried side by side, first their bones and then even their coffins breaking down as the dark earth reclaims them. In the end, the totemistic pipe and locket that Faret had used as shorthand for each member of the pair are all that remain, and they too are disintegrated and consumed before the final black panel. A realist might question the staying power of a corncob pipe in a grave, while a reader partial to extremes might miss a full-fledged depiction of dead bodies rotting away into nothingness (admittedly this is where my sympathies lie), but both critiques are superfluous to the sequence’s purpose, if not its power. In these final pages, Faret unearths an unspoken element of “Danny Boy” and puts it on display: The song’s final line is “And I shall sleep in peace until you come to me,” but of course at that point in the song the child has already returned, is in fact kneeling on the grave. It’s death the parent is looking forward to sharing with his child, because only then will their reunion be complete. Faret shows what that would look like, taking the original and adding a stanza of her own.

Those final pages present a potentially rewarding path for Faret to follow as an interpreter of existing stories. It reflects the same sensibility on display in, say, her luminous, horror-tinged scratchboardillustrations for Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. Though the whole point of Miller’s witch-hunt parable is that the thing was bunkum, Faret casts her cast of goodwives in a seemingly supernatural light, suggesting that terrible forces and tremendous powers were in play here — just not in the way the persecutors believed. Neither here nor in the end of Danny Boy is Faret indulging in the aforementioned glurge, lacing contemporary mores into past events in order to make readers feel good about their unearned ethical superiority (though she’s not entirely immune to this temptation); rather, she’s tapping into ideas and sentiments present in the characters and giving them freedom to manifest themselves in ways the characters could never do. Danny Boy may be a failed experiment, but in conducting it Faret has collected data that could well yield happier results a season or two down the line.

I reviewed Danny Boy by Kjersti Faret for The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Configurations

July 30, 2014I hesitate to use the formulation “more than just a comic” in describing “Configurations”, the recent webcomic series Aidan Koch published through TCJ contributor Frank Santoro’s Comics Workbook tumblr. Comics are whatever you put into them, and “Configurations,” certainly a comic, puts in plenty. But it feels less like a strip you read and more like a participatory event. It’s the rare experimental work that makes you feel as though you’re there in the lab with its creator, conducting that experiment yourself.

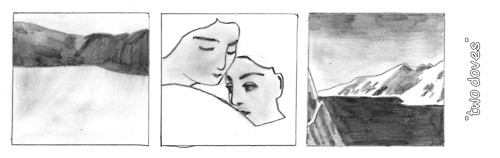

Comics Time: This One Summer

July 24, 2014At the beginning of This One Summer, its main character, Rose, splashes down into her bed, holding her nose and falling backwards as if leaping off a dock into the lake nearby. At the end she and a friend dig a hole in the beach big enough to contain her, and she lies in it, posing for her last picture of the summer — this is how she wants to remember it. In between, nature, as drawn with preposterous skill by Jillian Tamaki, proves capable of enveloping her without her help. Big summer-night skies, full of stars and moonlight. Bright summer sun, hanging overhead like it will never set again. Wet, heavy summer rain, seemingly just as endless, pouring into puddles drop after drop. Trees and vines and bushes and grass and undergrowth, verdant, overripe to the point of hysteria. The lake, which is alternately drawn dominating a spread vertically like a monolith, suspending the joyous bodies of tumbling teenagers in its inviting murk, and enveloping them like a sunlit shroud when they no longer wish to be found. Against this brush-stroke backdrop stand Rose and the other impeccably cartooned characters, whose stylized simplicity (relatively speaking; no sense that these are real people is lost) when juxtaposed with those wall-of-sound environments makes them feel like inner tubes bobbing in the water, or stones tossed in it. Immersion is This One Summer‘s strength, and it works alarmingly well for the story that cousin-collaborators Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki are telling. It’s a young-adult graphic novel, and young adults are constantly tossed into new circumstances by forces beyond their control, from puberty to parents. Out of their depth, do they sink or swim?

I reviewed This One Summer by Jillian Tamaki and Mariko Tamaki for The Comics Journal.

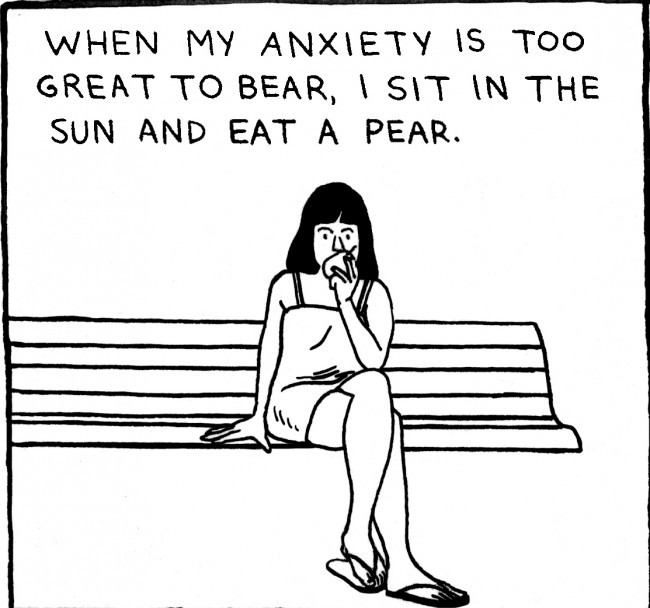

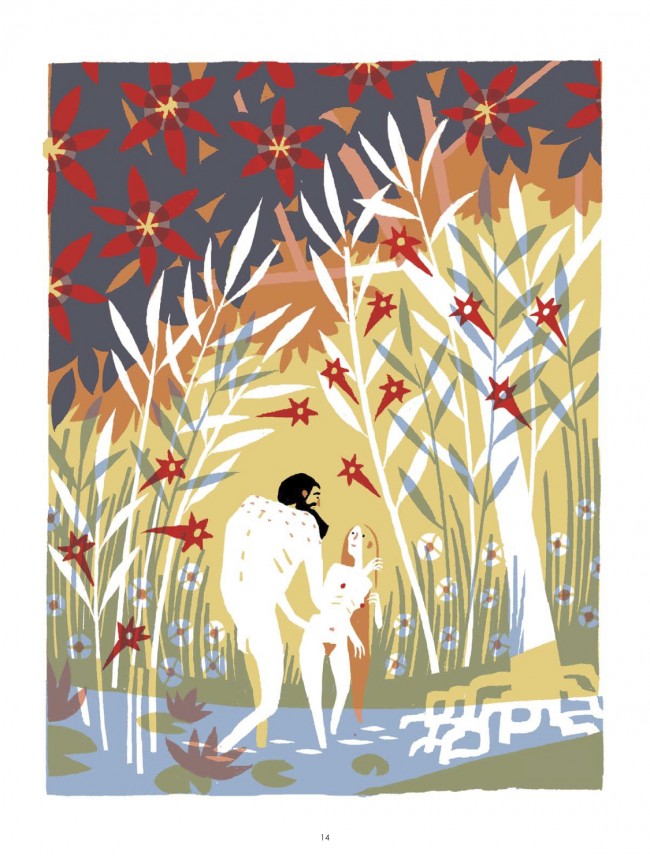

Comics Time: How to Be Happy

July 24, 2014The first moment — but certainly not the last — that made me stop reading How to Be Happy, turn back the pages, and immediately re-read them came early. “In Our Eden”, the lead-off piece in Eleanor Davis’s masterful new collection of short stories, concerns a back-to-nature commune driven to dissent and dissolution by its founder’s purity of vision. Some members chafe at the convention by which every man is called Adam, every woman Eve. Others fall away when the leader, a towering and barrel-chested figure with a ferocious black beard like something out of a David B. comic, takes away all of their prefab tools. The rest depart when he insists they neither farm nor kill for food, literalizing and reversing the Fall’s allegory of humanity’s move from hunter-gatherer to agrarian societies. At last it’s just this one Adam and the Eve he loves. By the next time we see them, Adam’s gargantuan physique has been pared away, his ribs visible, his nose reddened for a sickly effect, demonstrating Davis’s remarkable ability to wring detail and expressive power out of the simple color-block style of the piece. He comes across Eve, nude and stork-skinny, washing her long hair in a river. He goes to her, nude himself. “I’m ready for the bliss to come,” he says right to us in one of the recurring panels of first-person narration that have been peppered through the comic. They embrace. “I’m ready for the weight to lift.” They kiss.

I turned the page, curious as to how the story would end. Some final irony? Some subtle but biting indictment of utopian folly? A widening of the view to deny the lovers centrality in their world? None of the above: the story had already ended. The build-up I’d read into it — a crescendo of extremism that would end with Adam’s hubris exposed and exploited — didn’t exist. The easy climax, the stacked-deck scenario so common in stories about true believers in which author and audience get over at the expense of the characters when the latter are made to look foolish for foibles the former recognize instantly, never comes. The climax had come two pages before, when I turned from one page to the next and reached a splash-page image of the moment when Eve turns to see her Adam. This moment of connection is the story’s resolution. The use of Adam and Eve’s human bodies to communicate to one another, to seek the bliss that’s coming, to lift that weight, is the image Davis wants us to leave with. No moral, no punchline, no muted epiphany — discarded along with all the other distractions, they leave only Edenic bliss behind.

I reviewed Eleanor Davis’s masterful comics collection How to Be Happy for The Comics Journal.

Comics Time: Sorry Kid

June 26, 2014Sorry Kid folds out like a 22×17 broadsheet. When examined closely, it reveals itself to be two 11×17 pages, their surface murky with black xerox ink, joined together by sparkly rainbow-silver tape. This juxtaposition in its construction encapsulates the eight-page whole, which sees Clark alternate heartrending grappling with the overpowering grief of her father’s death and small welcome gestures in the direction of comfort.

All of the text is borrowed from apparently much-loved sources: Inside, writer Hélène Cixous’s novel on this theme; Ursula K. Le Guin’s fantasy classic The Farthest Shore; the Cocteau Twins song “Know Who You Are at Any Age”. It’s a tacit acknowledgement that recognition of your pain in painful work is often as comforting as can be.

I reviewed my first comic in ages, Sorry Kid by Katrina Silander Clark, for The Comics Journal.

Comics Criticism

November 8, 2013Last week, Frank Santoro interviewed me about the state of comics criticism for his column in The Comics Journal. Frank and I were concerned about the seemingly dwindling pool of people writing substantial reviews of alternative/art comics and all the attendant problems — the still smaller number of women writing about them despite the huge number of women making and reading them, the lack of critical evaluation provided to the newest generation of artcomix makers, the outsize influence of the foibles of those of us who are left, and so on. The interview sparked responses from Ng Suat Tong, Heidi MacDonald, and Frank himself that are worth reading, as are the comment threads attached to all those posts (particularly this comment by Peggy Burns); I also got a lot out of the twitter exchange I had with Sarah Horrocks.

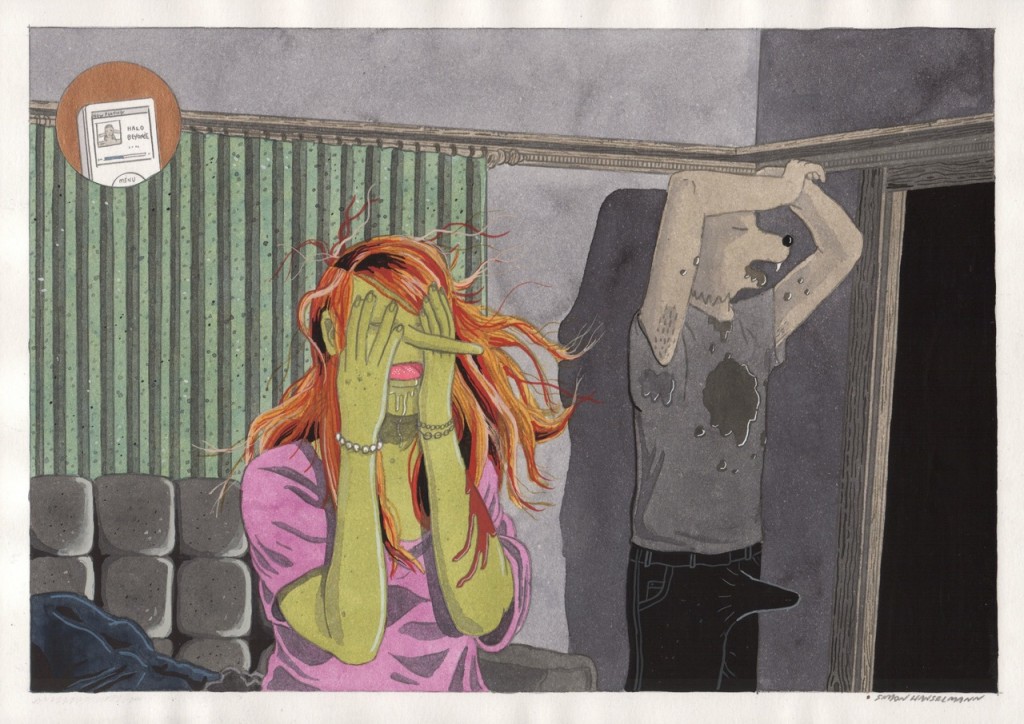

“Disgusting Creatures”: The Simon Hanselmann interview

June 6, 2013I interviewed Simon Hanselmann, creator of Megg, Mogg, and Owl, for The Comics Journal. We’ve both been looking forward to this for a long time, and I’m as proud of it as I’ve ever been of an interview I’ve done. Please check it out.