Posts Tagged ‘the big lebowski’

172. Lebowski (III): Korea

June 21, 2019Brad Wesley may bear a closer to resemblance to a very different captain of a very different industry from The Big Lewbowski, but in recasting the Korean War as a crucible for personal growth rather than the grotesque slaughter of a country by warring empires he has more in common with Jeffrey Lebowski than with Jackie Treehorn. (As far as we know, anyway; it’s entirely possible Jackie Treehorn froze his dick off in early 1951, leading to his belief that the brain is the biggest erogenous zone.)

When Wesley came to Jasper after Korea, he tells Dalton, there was nothing. His ambition stems, then, from a kind of horror vacui; this would account for his work in the area as a developer, entrepreneur, and establisher of the area’s first Slurpee machine, and it may stem from his experience with privation during that grim time overseas. For the Big Lebowski, Korea afforded him the chance to tell a non-sob-story sob story, about how a gentleman from the People’s Republic cost him his legs, but excuse me sir, spare me the pity and hold back the handouts, everything he’s done since is a testament to his indomitable will to achieve, legs or no.

In both cases the Korean Character-Building Exercise did precisely nothing to make either of these men worth more than a pisshole in a snowbank. Lebowski married into money, and his avant-garde artist daughter Maude allows him the fig leaf of a charitable foundation and a trophy wife to keep him from blowing her late mother’s fortune. Wesley built a mall and some strip-mall stores and hires semi-competent legbreakers to bust up auto-repair shops and dive bars to keep the locals in line. Both men wind up lying on the floor of their own palatial homes in humiliation and defeat by the end of their respective films, though Lebowski at least is still a going concern afterwards, which is more than we can say for Jasper’s JC Penney baron. The paths of glory lead but to Frank Tilghman’s shotgun and Walter Sobchak’s misdiagnosis of paraplegia.

073. Lebowski II: Garden Parties (continued)

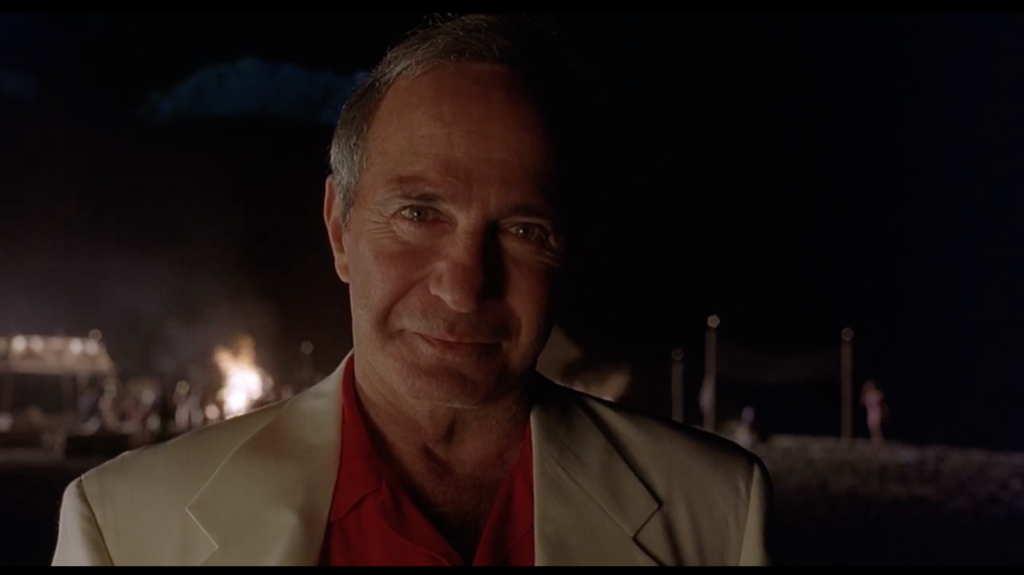

March 14, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a shady business mogul played by Ben Gazzara flouts decency standards in a waterfront community that he controls through a combination of extravagant wealth and muscular morons. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film in which Gazzara reprises this role.

The two orgiastic parties thrown by the Gazzara characters in these movies, Malibu pornographer Jackie Treehorn in the latter and Jasper JC Penney enthusiast Brad Wesley in the latter, have so many surface-level similarities it remains difficult for me to believe that Joel and Ethan Coen were not familiar with Rowdy Herrington’s masterpiece when they made their own. Smiling men tossing topless women through the air, the bright blue of a pool juxtaposed against the dark of the night, a general “the night time is the right time” atmosphere, the dramatic entrance of the Gazzara characters themselves, goons—it’s all there.

Yet the differences reveal much, as they typically do, even as they point to how similarly the two films often function. I vividly remember going to see Lebowski at the movie theater when it debuted and finding it a sensational film, in the sense that on a scene-by-scene basis I felt buffeted by new and unprecedented forms of ridiculousness. The Treehorn beach party is way way up there on the list, beginning as it does with a topless woman plummeting through a void with the otherworldly voice of Yma Sumac blasting at full volume. This is the impression Treehorn wished to make on the Dude as well, whom he used his goons to summon to his estate, impressed with the excess and splendor of his lifestyle, lulled into a false sense of security, drugged, and dumped in the street. It was a party for himself and his, I dunno, friends I guess?, but it was also a performance for one Jeffrey Lebowski. Treehorn’s direct-address introduction of himself right into the camera speaks to that.

Brad Wesley’s idiotically raunchy shindig has no such purpose. He and his men and women have no idea Dalton is watching from across the river; indeed it’s unclear if at this point in the film Wesley has any idea where he lives at all, and furthermore Dalton makes an effort to hide his observation of the party by switching off the light by which he was reading a Jim Harrison novel when the noise of the soiree first distracted him. Additionally there is nothing particularly disorienting or otherworldly about this parade of gawping meatheads and Mötley Crüe video extras—they simply run out of Wesley’s house in a surprisingly orderly line, start stripping off their clothes (“hot babe” bikinis for the women, the usual thug-casual style for the goons), and boogie down to Bob Seger’s “Monday Morning” of all things. Wesley arrives last but he incorporates himself into the festivities rather than set himself apart, joining his girlfriend Denise and pinching the cheek of Mountain, his tallest and goofiest goon. Where the Dude is duly impressed by Treehorn’s milieu (“Completely unspoiled!”), Dalton is merely amused by Wesley’s, a fair and perhaps even generous reaction to a party at which a central component is Terry Funk with his pants around his ankles.

The point I’m trying to make is that while the Ben Gazzara party scene in The Big Lebowski serves a concrete purpose for the Ben Gazzara character, the Ben Gazzara party scene in Road House exists simply to entertain an audience the film presumes to be pretty stupid, or at least open to enjoying pretty stupid things. Dalton, a man of diverse interests, enjoys it just fine. Thus Wesley’s power to impress and intimidate Dalton with his Dionysian powers is dissipated. When he finally does attempt to bowl the cooler over with demonstrative partying and sexuality deep into the film, when he has Denise strip at the Double Deuce as a show of masculine force, Dalton is completely impervious. This party is a vaccine.

072. Lebowski II: Garden Parties

March 13, 2019028. Lebowski (I): Windshields

January 28, 2019Road House is a 1989 film in which a grizzled gray-haired man with a molasses drawl played by Sam Elliott dispenses wisdom to a practitioner of tai chi who finds himself at odds with a rich, sleazy business magnate with a personal goon squad played by Ben Gazzara. The Big Lebowski is a 1998 film about same.

We will be revisiting the Road House/Lebowski Cinematic Universe. Boy, will we! But for now let’s focus on what I like to call The Windshield Shots. In Road House, Wade Garrett has just arrived in Jasper, Missouri to lend a hand to his old running buddy Dalton as the latter wages an increasingly vicious war with Brad Wesley, the film’s Gazzara. After rescuing his ass from a four-on-one beatdown—seriously, they’re just holding him in place and punching him in the gut like he’s a human heavy bag when Wade finally shows up to save the day—Wade goes for a drive in the passenger seat of Dalton’s car, the abuse of which by the angry patrons of the Double Deuce is a running gag, one that runs too far by any reasonable standard in fact. For that reason, riding shotgun puts Wade in an unenviable position.

But look at Wade here. He’s tickled pink! I assume he likes the feel of the wind through his magnificent head of hair, but it’s more than that. We will see, time and time again, how his most dangerous and dirty exploits amuse him, and how the same is true of Dalton’s. Riding through Jasper with a gigantic hole of shattered glass in front of him reassures him that it’s business as usual for his treasured “mijo.” It’s a sign that Dalton’s pissing off all the right people. And since Wade is a firm believer in the cut-and-run strategy when shit gets too heavy, he’s no doubt aware that the car will not long outlive Dalton’s stay in town, however long that may be. “It seems to me you’d be a little more more…philosophical about it,” he says later (much later) that evening, about an entirely different matter. But that hole in the glass, framing his “Aw shit-hell kid, I’m in hog heaven” grin, is already our lens into the Wade Garrett Mindset. He looks at broken things and sees a chance to live a life defined more by parts than the whole they add up to. Moving from one sensation to the next, treating calamity as opportunity, riding the nightlanes, bound only to those who ride with him: That is Wade Garrett. All Dalton can do is grin and bear it. Currently, it is time to be nice.

The Lebowski triarchy is an entirely different matter. Put aside whatever this Windshield Shot does or doesn’t owe to its predecessor. (I certainly believe the Coen Brothers, who after all put Sam Elliott and Ben Gazzara in their movie about a pair of weirdos fending off some rich guys and some goons, had seen Road House, but it’s irrelevant.) Despite sharing the tonsorial sensibilities of Wade Garrett, the Dude, played by Jeff Bridges, is pointedly not enjoying this breezy night drive. There will be no next down for him to head to. His car is not something he can stand to sacrifice. The Dude does not abscond. The Dude abides. He’d prefer to abide with a windshield.

Walter Sobchak occupies the Wade position in the car, but again, the contrast is revealing. No smile for Walter, no “shyush, don’t this beat all” grin. Walter is a man who can never admit that things have not gone according to plan, that every eventuality has not been foreseen and warded against. If at the beginning of the evening he said they would swing by the In-N-Out Burger, then goddammit that’s what they’re doing. If, in the interim, they attempt to brace a teenage boy for money he didn’t steal, vandalize a car he didn’t buy, and antagonize the neighbor who is the real owner of the car until the Dude’s own vehicle winds up getting the worse of it…well, the In-N-Out’s still there, isn’t it? Then he’ll by god buy it and eat it. As he says elsewhere in the film, “I’m staying. I’m finishing my coffee. Enjoying my coffee.” Situation normal, et cetera et cetera. Ironically, only his fellow veteran of American imperialist adventure in East Asia, Brad Wesley, shares this need to control the narrative.

Oh, Donny? Donny’s literally taking a back seat, literally a few steps behind. (Windshield’s out, Dude.) Lacking any physical or intellectual agency, he’s just along for the ride. He has no character in Road House. Unless…unless…