Posts Tagged ‘real life’

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Ten: “Thorny Politics”

March 18, 2016Which brings us back to both the nonexistent investigation into deaths incurred during the search and rescue attempt and Trump’s hang-‘em-high routine. Who’s to blame for the Bergdahl debacle? The Obama Administration certainly broke the law by not informing Congress of its intentions, though as Koenig points out this is hardly unprecedented where the invocation of executive authority is concerned. And pretending there’s no evidence anyone died because of Bergdahl’s actions when the truth is no one ever bothered to try to collect any is impossible to excuse. Civilian oversight of the military is vital to a democracy, even when those civilians are Republican congresscreeps. At the same time, the Administration lied to Congress because Congress, and the entire Republican governmental, political, and media apparatus, has made it a matter of course to deny Obama anything he wants, ever, as well as maintain an hysterical level of fear-mongering about the Gitmo detainees (whose detainment, by the way, is also completely illegal, though you don’t hear HASC complaining there) and terrorism generally. Distrust met with distrust, intransigence with mendacity, illegality with illegality, until traditional political action became impossible. The result: an escalating pattern of hatred of the political enemy and a precipitous loss of faith in the existing institutions to do anything about it. Thus, a market is created: Gee, if only someone whose hatred of the enemy and contempt for the institutions could, somehow, make America great again.

How the battle over Bowe Bergdahl prefigured the rise of Trump: this week in my review of Serial.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Nine: “Trade Secrets”

March 5, 2016Serial Season Two is a lot like the Afghanistan peace process, actually. Good intentions? Check. Grand plans? Check. The slow collapse of both due to institutional unsuitability to the task at hand? Check. There’s a great story to be told about the capture and release of Bowe Bergdahl. There’s a great story to be told about the decade-plus-long attempt to get us out of the mess we made in the country where he was captured. There’s just not a great story to be had by wedging the latter into the former on a podcast.

I reviewed this week’s rambling episode of Serial for the New York Observer.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Eight: “Hindsight, Part 2”

February 21, 2016This time, we’re not just counting on fellow soldiers and childhood friends to explain just how ill-suited Bowe and his delusions of heroic grandeur were to army life—we’ve got the man himself. In an interview with screenwriter Mark Boal, Bergdahl describes himself as “lost in the fantasy” of being a soldier—not the modern-day kind, the only variety actually on offer, but a mythologized hybrid of soldiers from World War II, the 1800s, the era of the samurai, and the completely fictional world of kung-fu flicks. Bergdahl’s conception of the soldier’s life was entirely based around outmoded, if not outright invented, ideas of valor and honor. Bowe realizes his viewpoint was not realistic, but sticks with it nonetheless, insisting that the conditions he found unacceptable “shouldn’t be acceptable to anyone.” And since he believes in the bushido code, he doesn’t take any of the more readily traveled roads available to him, from speaking with an embedded reporter (not soldierly enough) to contacting any one of the dozens of officers at the forward operating base he was at days before he wandered off (not heroic enough). Reality had disappointed him, and the ideas he’d generate to reclaim his fantasy would be invariably grandiose—and doomed to failure.

What better writer to give voice to this childlike view than the philosopher queen of take-my-ball-and-go-home right-wing extremism, Ayn Rand? Bergdahl’s friends groan to Koenig as they recall a group email he sent out just prior to his departure, titled “Who Is John Galt?” and cribbing extensively from the Objectivist ur-text Atlas Shrugged, demanding that institutions shape themselves around men of worth, not the other way around. A copy of the novel winds up arriving at his old friend Kim’s house, along with his valuables, days after his disappearance. It’s a shame, in a way, that Bergdahl didn’t go into politics, where Objectivism is often a ticket to the august ranks of the United States Senate and a subsequent failed mid-tier presidential primary campaign. Instead, he went into the Army and “went Galt” when the system failed him, demanding it all grind to a halt in his service. The results were entirely predictable.

I reviewed the second installment in last week’s Serial doubleheader for the New York Observer.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Seven: “Hindsight, Part 1”

February 21, 2016Over the episode’s relatively short running time of 38 minutes, Koenig presents a litany of first-hand testimony to Bergdahl’s unique psychology. She begins with the many, many soldiers who highly doubt his retrospective rationale for running away from his post, arguing he had years to cook up this flattering story. Some proffer an alternate theory: According to them, Bergdahl sometimes wondered aloud about faking his death, going AWOL, running off to Pakistan, making his way to India, joining the Russian mafia, working his way to the top as a mercenary and hitman, killing the boss, and taking over. Hey, he’s nothing if not ambitious! In the end the story is even less credible and logistically possible than Bergdahl’s version, but it speaks to his overwhelming desire to be seen as a great warrior, a self-made ubermensch.

If this version of Bergdahl is a bit on the Bane side, interviews with earlier acquaintances paint him as more of a Batman type. Growing up isolated and homeschooled on a remote farm, Bergdahl eventually fell in with a slightly artsy crowd clustered around on a performing arts center and teahouse in a nearby town. There he learned how to fence, became famous among his circle for testing his own mettle (seeing how long he could go without speaking, punching trees and rocks to strengthen his hands), and began amassing makeshift weapons to protect his little clique in the event of…god knows what. His friends describe him as a young man obsessed with the concept of virtue and determined to arrive at his own definition rather than follow someone else’s. What he came up with—basically, you can only be a good person if you’re doing everything in your power to solve any problem in the world that you can observe—could be considered crippling in its impossibility to implement…if your goal really was to ameliorate every problem you encounter. If your goal is to be seen as the kind of man who does that, by both yourself and others, then the course is a bit clearer. For Bergdahl, who friends say wanted to be seen as “a silent protector” of the innocent, it was plain as day.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Six: “Five O’Clock Shadow”

February 8, 2016The contradictions inherent in Bergdahl’s personality emerge clear as day. It’s not that he’s opposed to danger per se; his DUSTWUN misadventure and his two subsequent attempts to escape from the Taliban prove that. Moreover, Koenig reports his friends and fellow soldiers recalling him frequently agitating for more engagement with the enemy, more “killing bad guys.” Not that he’s there to “rape, burn, pillage, and kill,” mind you, to quote the gallows humor he reportedly took very poorly when a higher-up joked that this was not their mission in a briefing before deployment. Heaven forbid anyone believe Bowe Bergdahl is anything less than a real American hero! He was equally keen on COIN, the well-intentioned but impracticable boondoggle of a military doctrine whereby soldiers slowly gain the trust of the locals and cut off insurgents’ support at the roots, effectively impossible to do in a series of brief months-long rotations. Sgt. Bergdahl was there to help, goddammit, to fight for truth, justice, and the American way. It wasn’t danger he feared, it was danger that didn’t help him prove he’s a supersoldier, a man of honor and valor, a true knight. (This was the thinking behind his pointless acts of Arthurian self-abnegation, like sleeping directly on his bedprings instead of a mattress and snuggling a tomahawk to sleep every night.) Getting yelled at bothered him because he expected a hero’s welcome; not receiving it was tantamount to a threat against his personal safety. And if he couldn’t be a hero playing by the rules, then by god he was going to break them. Thus was the ludicrous AWOL mission that began the season conceived.

I wrote about Bowe Bergdahl deciding his life was in danger because he got chewed out over a dress code violation, and what that means about him and the show covering him, in my review of last week’s Serial for the New York Observer.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Five: “Meanwhile, in Tampa”

January 25, 2016Ronald Reagan once said “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.” Far be it from me to encourage a journalist to heed the words of the Gipper—explaining is what journalists do, after all—but in the case of Serial, he’s got a point. “Our one story, told week by week, will now be week biweek,” Sarah Koenig announced on last week’s non-episode episode of her podcast. “Get it?” she asked, before answering her own rhetorical question in the negative: “No? ‘Biweek,’ like ‘biweekly’? B-I-weekly?” We’re not 15 seconds into the announcement that Serial is shifting to an every-other-week schedule before Koenig begins apologizing for her own writing. “Sorry, that’s a pun that only print could love, and I just tried to pull it in an audio story.”Could print love that pun, though, really? I mean, you tell me. I just wrote it up, it’s sitting there a few lines above this one, and “biweek” still isn’t an actual word, printed or no. To paraphrase Harrison Ford’s famous critique of George Lucas: Sarah, you can type this shit, but you sure can’t say it. Maybe you shouldn’t type it either.

But that’s Sarah Koenig’s Serial for you. Once this procrustean podcast has settled on an idea and a format, it’s by-god sticking with them, no matter how little sense that makes. Of course, forcing a pun that she admits almost immediately doesn’t work is the least of Koenig’s problems in that regard. Now that “Meanwhile, in Tampa,” the series’ delayed fifth episode, is finally up and running, it’s apparent that the show’s difficulties are only intensified by the biweekly schedule. Whether told week by week or week biweek [sic], this “one story” has yet to be presented in a way that justifies its telling at all.

I reviewed last week’s Serial, or really just Serial generally, for the New York Observer.

Vic Berger IV Is Vine’s Strangest Political Satirist

January 7, 2016Fallon doesn’t want to offend. I am sure he is the nicest guy, and would be super fun to hang out with, but his show appears to be this platform where anyone can come on and paint themselves however they want to appear. My annoyance with him started with Chris Christie constantly being on there, dancing around and doing his dumb skits about how much he loves Springsteen. Christie is such a gross and horrible person. I worked for a decade for the state of New Jersey and can truthfully say he’s done way, way more harm for the state than he’s done good. And the whole shutting down of the bridge bullshit? He denies it all, and then the next thing you see is him on Fallon making light of it and singing a song about it or whatever. Fallon lets these terrible people saywhatever they want. Not that the host of The Tonight Show needs to be a hard-hitting journalist getting to the bottom of things—it’s just that if he’s going to have these people on, at least have some point of view. Don’t just laugh nervously about it. I mean, one of his questions to Christie was, “Heard you hung out with the Romneys! So how are the Romneys? They’re all awesome.”

The other thing about Fallon that drives me crazy is how he will have a guest on and then bring out an iPad and try out some app with them. It’s unbelievable. There are segments where there’s like 30 seconds of him staring silently at an iPad wearing earphones. I’ve made a few Vines using those moments.

Over at Vice I interviewed the brilliant, brutally funny video editor Vic Berger IV, Vine’s strangest political satirist, about his five muses: Jeb Bush, Donald Trump, Chubby Checker, Jimmy Fallon, and Jim Baker.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Four: “The Captors”

January 7, 2016With a shorter runtime, a tighter focus, a different remit, Serial Season Two could be a harrowing account of life in captivity. Or it could be an unsparing look at the damage America’s torture of prisoners has done to our moral standing and to the individual lives of its victims, theirs and ours alike. Or it could be an examination of military justice, sentencing, and whether Bergdahl’s prospective punishment fits the crime. Or it could be a look at the lives of Taliban fighters, Haqqani operatives, and the civilians upon whom they rely for support, seen through the window of this one event. Or it could expose the truth, or lack thereof, behind the allegations Bergdahl leveled at his commanders, the allegations that prompted his flight and led to his capture, the allegations the show still hasn’t spent so much as a word detailing. It could be any one of those things. Instead, it’s…this. It’s a weekly slog through an overstuffed tale that simply can’t justify the telling, not in this way. As James Whiting, one of of the Evil Newspaper Editors in The Wire Season Five, put it, “If you leave everything in, soon you’ve got nothing.” In this case it’s actually true.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Three: “Escaping”

December 27, 2015Koenig notes that this second escape attempt puts paid to the notion that Bergdahl’s a Taliban sympathizer. He’d already been badly beaten as punishment for his first escape; why risk going through that again if he thought these people had some good points? Indeed, the severity of his treatment also calls into question the Army’s decision to prosecute Bergdahl now. If all he’s really guilty of is being a big enough moron to think he could Jason Bourne his way from one base to another in order to call attention to a commanding officer he hated (for reasons still unstated), hasn’t he suffered enough?

But the escape attempts could also be seen as part and parcel of the instinct that drove Bergdahl to run in the first place. He’d already constructed a heroic narrative for himself in which he would address a problem of great moral risk (the Army’s horrible commanders) by taking a great physical risk (going AWOL and making his way through enemy territory). How could a man like that not take his chances trying to escape? Succeed or fail, it would feed into that same legend-in-his-own-mind attitude.

I reviewed the third episode of Serial for the New York Observer.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode Two: “The Golden Chicken”

December 21, 2015By the time Serial Season Two debuted its second episode this morning, events on the ground had already overtaken it. The Army announced on Monday that Bowe Bergdahl will be court-martialed for desertion and “misbehavior before the enemy,” a serious charge that could earn him a life sentence. Sarah Koenig spent the opening minutes of the podcast detailing this turn of events—an outcome that both the Army as an institution and hawks like Sen. John McCain have backed for some time, but which, she says, flies in the face of the opinions of officials who’ve gotten to know Bergdahl personally. For the purposes of Serial, though, the decision is largely immaterial, since it will likely be weeks before we reach this point in the narrative Koenig and company have constructed.

That disconnect is revealing. When presented a choice between focusing on the facts at hand and wandering back into its rambling slow-reveal structure, Serial chooses the latter every time. No wonder the show settled on Bergdahl for its subject this season: When it comes to wild schemes that leave you lost in the wilderness, no closer to the truth you set out to expose, they’ve got something in common.

“Serial” thoughts, Season Two, Episode One: “DUSTWUN”

December 14, 2015“War is too important to be left to the podcasters.”—Gen. Jack D. Ripper,Dr. Strangelove (paraphrased)

NPR journalist Sarah Koenig’s unlikely cultural phenomenon has its problems, but laziness in the advancement of its narrative is not one of them. How else could you characterize a show that spells out all of its major problems in a single sentence early in its Season Two premiere? Describing her production partner, Zero Dark Thirty screenwriter Mark Boal, and his discursive 25-hour taped conversation with infamous POW/deserter/whistleblower/traitor/fill-in-the-blank Bowe Bergdahl, Koenig says, “Mark isn’t so much after the facts of what happened, though he wants those too, but more, he’s after the why of what happened—trying to get inside Bowe’s head, to understand how Bowe sees the world.” The reliance on an entertainer of dubious reputation to acquire reportorial truth; the elevation of unknowables like intent over tangible, verifiable, old-fashioned who what when and where; the conviction that a self-described Jason Bourne wannabe has valuable, if not unimpeachable, insight into both his actions and the environment that produced them—the immensely popular podcast’s trifecta of fatal flaws are all right there. The message is as unmistakable as it is unintentional: Question the clarity of Serial’s storytelling at your peril, people.

The Boiled Leather Audio Hour Episode 42

October 21, 2015Fire and Blood: The Third Reich

We’re traveling from Westeros to Nazi Germany in this unusual—and, to us, urgent—episode of the Boiled Leather Audio Hour. Why are we venturing so far afield from our usual topics of discussion and debate? Because we’ve always believed that A Song of Ice and Fire, like life itself, is best viewed through an unsparing ethical and historical lens. Lately, however, that lens has been clouded. In recent weeks, numerous right-wing politicians—most notably Republican presidential candidate Ben Carson and his supporters in the United States—have distorted and repurposed the rise of Adolf Hitler and the roots of the Holocaust to suit their preexisting positions. Astonishingly, in the day since this podcast was recorded, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu followed suit. We believe this to be an act of tremendous disrespect for the dead, one that also does a grave disservice to the living. Given our personal and professional interests in this pivotal epoch in history, which have shaped our interaction with ASoIaF in ways large and small, we decided to explore the era’s real lessons as best we could.

What role did privately held weaponry and paramilitary organizations actually play both in the Nazi Party’s ascent to power and the resistance against it? How should we view Europe’s failure to act in the face of Hitler’s belligerence, and Germany’s failure to capitulate in the face of certain defeat? What parallels can be drawn between the forces that fueled the war Hitler ignited and those at play in Westeros and Essos? What makes World War II different enough from other conflicts for the likes of Vietnam-era conscientious objector George R.R. Martin to say it was worth fighting? Is there such a thing as a “good war” at all? In this experiment of an episode, we try to answer those questions.

Two notes before we proceed:

1) We are deeply indebted to the work of the historians Ian Kershaw and Richard J. Evans, particularly Kershaw’s two-volume Hitler biography and Evans’s Third Reich trilogy.

2) On a much lighter note, this episode (hopefully—with iTunes, god only knows) marks the debut of our brand new logo, created by Sean’s partner, Julia Gfrörer. We are in her debt.

Additional links:

All Leather Must Be Boiled’s Ian Kershaw tag.

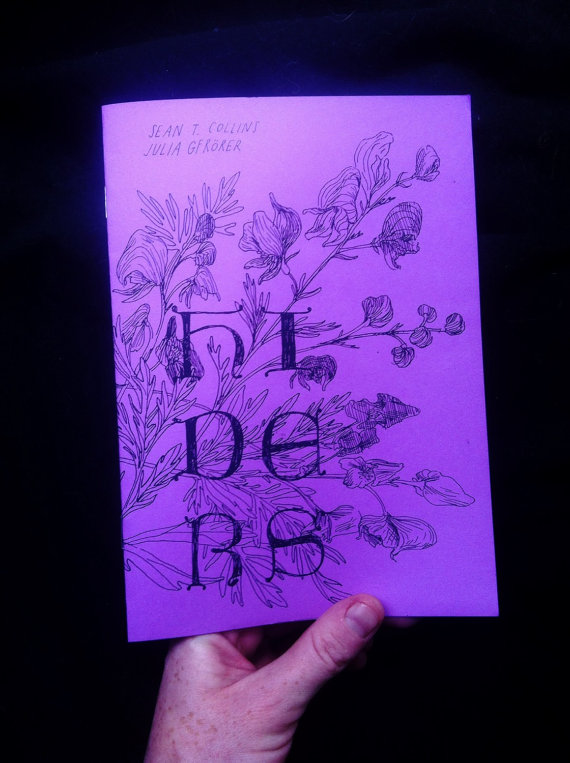

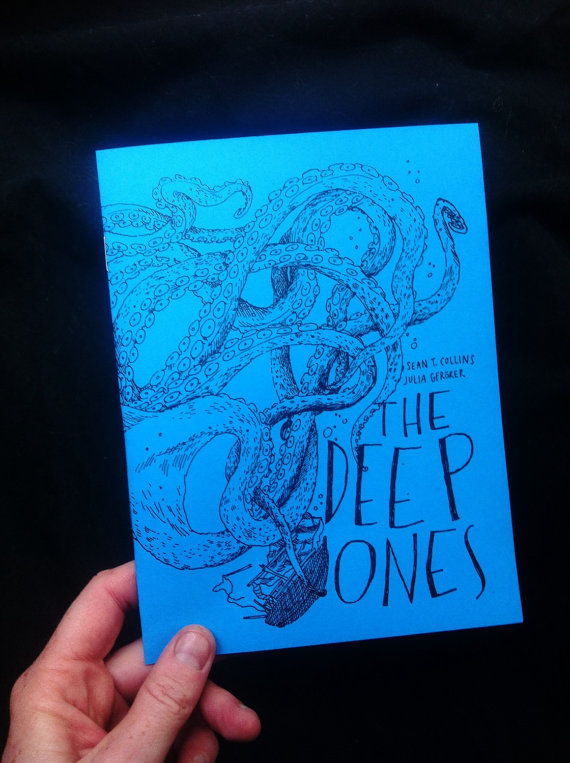

Hiders & The Deep Ones

September 28, 2015Hiders and The Deep Ones, my two most recent comics with Julia Gfrörer, are now available for purchase as minicomics at Julia’s Etsy store.

9.11.15

September 11, 2015As he followed her inside Mother Abagail’s house he thought it would be better, much better, if they did break down and spread. Postpone organization as long as possible. It was organization that always seemed to cause the problems. When the cells began to clump together and grow dark. You didn’t have to give the cops guns until the cops couldn’t remember the names…the faces…

Fran lit a kerosene lamp and it made a soft yellow glow. Peter looked up at them quietly, already sleepy. He had played hard. Fran slipped him into a nightshirt.

All any of us can buy is time, Stu thought. Peter’s lifetime, his children’s lifetimes, maybe the lifetimes of my great-grandchildren. Until the year 2100, maybe, surely no longer than that. Maybe not that long. Time enough for poor old Mother Earth to recycle herself a little. A season of rest.

“What?” she asked, and he realized he had murmured it aloud.

“A season of rest,” he repeated.

“What does that mean?”

“Everything,” he said, and took her hand.

Looking down at Peter he thought: Maybe if we tell him what happened, he’ll tell his own children. Warn them. Dear children, the toys are death–they’re flashburns and radiation sickness, and black, choking plague. These toys are dangerous; the devil in men’s brains guided the hands of God when they were made. Don’t play with these toys, dear children, please, not ever. Not ever again. Please…please learn the lesson. Let this empty world be your copybook.

“Frannie,” he said, and turned her around so he could look into her eyes.

“What, Stuart?”

“Do you think…do you think people ever learn anything?”

She opened her mouth to speak, hesitated, fell silent. The kerosene lamp flickered. Her eyes seemed very blue.

“I don’t know,” she said at last. She seemed unpleased with her answer; she struggled to say something more; to illuminate her first response; and could only say it again:

I don’t know.

–Stephen King, The Stand

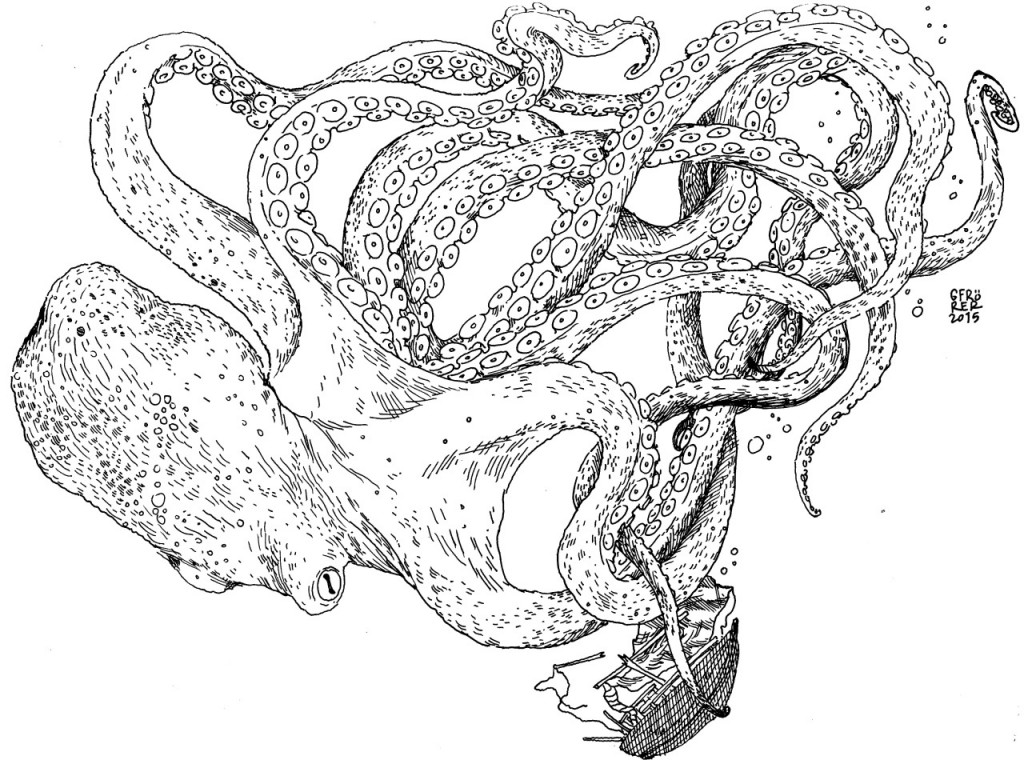

The Deep Ones in print, coming soon

September 9, 2015This is the cover illustration for a print version of The Deep Ones by me and Julia Gfrörer, which we’ll be selling at SPX next week.

May 26, 2015

I was sexually abused when I was three or four years old. The exact date, like some of the specifics, is lost to my memory. As far as memories go I suppose this is one of my earliest, actually. My brain gives me gifts unasked for, sometimes.

I came under the care of two teenagers my family trusted. The elder of the two spent a week humiliating and abusing me. (The younger of the two saw everything and did nothing.)

She locked me alone in a room for hours, and forced me to work around the house, whatever that could have looked like for a three year old, when I was released. She fed me food she had rendered inedible through means I’m glad remain a mystery to me, and when I inevitably could not bring myself to eat it I went hungry. (At the time the only available category for bad food my brain had access to was “stale,” so that’s the description of the peanut butter and jelly sandwich she made me that I remember formulating. Whatever was wrong with that sandwich, which I can still taste in my mouth over 30 years later, it wasn’t stale bread.) She made fun of me constantly, exclusively. She made me wear diapers, which like all children I’d stopped using with pride, and when the time came to relinquish me back to my parents’ care she threatened that they would put me in diapers and keep me in them if I told.

On the day she gave me a bath, she made me stand naked while she examined and ridiculed me. I can’t remember if she touched my penis, honestly I can’t, but she must have: I had a birthmark or freckle on it at the time, which she mocked. I was a freckly kid, and my mother had told me freckles were where the angels kissed me before I was born. “Did the angels kiss you there?” my abuser asked, laughing. I didn’t recognize what was being suggested, obviously, fortunately, though I sensed it was bad. I looked down and saw something that, while neither repulsive nor ridiculous, was now alien to me. What I understood most clearly was that my private parts were no longer private. They could be seen and touched and kissed and made fun of and laughed at. I had no more power to stop it than I could force my mouth to chew and swallow the tainted food my abuser served me. Here was another plate.

I knew what had been done to me was mean, which is a child’s word for wrong. I knew I’d done nothing to deserve it, so I had nothing to fear if I divulged it. When this time period drew to a close I told my parents what I could immediately, without hesitation. That put an end to it.

Until recently I hadn’t thought much about this incident, or its impact on my life. I didn’t think there’d been one. After all, I was lucky in many respects. The abuse occurred over a discreet time period, rather than an ongoing one. The physical component could have been much worse. I was so young that I didn’t understand the sexual component to be sexual; certainly no one presented it to me as such after the fact. I didn’t yet feel shame, thank christ. Authority figures believed me and not my abuser. I know so many people who went through so much more. I am not the kind of person to cut himself slack for suffering.

Fifteen, sixteen years ago I rifled through my dad’s files and found a gifted-children evaluation that had been done on me prior to kindergarten. The evaluator noted that when given animal toys to play with, I had the predators menace the smaller animals until other, bigger animals came to fight the predators and rescue the prey. The evaluator ascribed this to the incident, but I’d always thought it was just how kids play. Isn’t all narrative conflict-driven? I put the report aside. I put the abuse aside.

I am currently at what I hope to be the tail end of a years-long bout of depression, and my life now is very different than my life before it began. My depression’s worst depths roughly coincided with the start of a period of intense sexuality. Given my interests as a critic and artist, this combination has been pretty fucking good for me, professionally. I write to figure things out; I figure things out when I write; this is true even when figuring things out is not the goal. I can’t help it. I am also fortunate enough to be in both a romantic relationship and a therapeutic one in which figuring things out is the goal. And so, inevitably, I’ve wormed my way back into this soil.

I’ve known for many years, because it’s been screechingly obvious to me even at my most oblivious, that sex is part of a cycle of humiliation and redemption for me. I was bullied badly in elementary school, and by middle school the teasing and mockery had hardened me into a fist of resentment against my social betters. By my sophomore year in high school it became apparent to me that I was now attractive to girls. This was great fun for all the usual healthy reasons, but I also saw it as slam-dunk evidence that I wasn’t the faggot and loser and geek and baby the male jocks said I was. Indeed, another human being need not be present for this catharsis to take effect: I felt a thrilling flash of “that’ll show them!” the first time I masturbated, because my body worked the way a man’s body should. Sex as a proving ground.

I identified this feeling early, but it never occurred to me to ask why I felt it. Why does the successful exercise of sexuality validate me as a person? Why does the mere fact of my sexual autonomy mean anything? Why does the concept of the body as a machine the operation of which exists outside normal social strictures of shame and propriety turn me on and get me off, ever since the very first time? If sex has taken on such importance in calibrating my personality, and if that calibrator was damaged by my abuse, were the parts of my personality that aren’t directly sex-adjacent able to be damaged as well? I don’t know.

I suspect, though. I suspect now. I suspect that at an age when I couldn’t imagine anything worse than being made to be a baby again, powerless and devoid of self-control, my abuser rooted my private experience of my body in a diaper. I suspect that at an age when every word from my mother’s mouth was love, my abuser used a story she’d told me to make me feel good about my body and hurt me with it, turned me against myself. I suspect that my baseline self-evaluation was reset at “not okay,” and that I grab what I can from outside and stand on it as long as I can to stay above it, which is never long enough. I suspect that anything that demonstrates that my body is my own and that my body is good is a balm to my soul but that its palliative effects only last so long. I suspect that I was conditioned to believe myself a shameful excess, a burden to everybody, and that my personal life has been an endless, futile scramble to make myself as unobtrusive and inoffensive as possible, to find solace only in hiding my own need.

I’ll never know, though. That’s the thing that bothers me the most: I’ll never know. This thing that happened to me, that was done to me, is dark matter. I know it’s there, but that’s all I know. Even if it were to have shaped me the way I suspect it might have, it’s convinced me I have no right to claim it as such — that the story’s not worth telling even if it’s mine to tell, since everyone has a story, don’t they, and if I went for all these years not thinking about it, not noticing it, even now I should just shut the fuck up about it, it’s vanity to pretend I have any reason to complain, you will be laughed at again, you are laughable again, how bad could it be? How bad could it be? I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know.

May 20, 2015

One thing you don’t realize until you have a child is that stories about redemptive, heroic violence are omnipresent. Once a child is past toddlerhood and demands narrative media of greater complexity, violent conflict becomes an inescapable requisite. Having a daughter adds a layer of complicity: Boys are fed this stuff automatically, but with a girl you so often deliberately expose her to violent stories that would not reach her otherwise for the sake of egalitarianism. To send the message to your kid that the boy/girl binary is false you’re stuck showing her “boy stuff,” invariably involving punching or lasers, or “girl versions” of “boy stuff,” which port over those values as a cost of increased dynamism on the part of the female protagonist.

Every story I love from childhood involves solving problems with heroic violence. How can I share that love with my kid without imparting that view? It took me three decades to shake loose of it myself. Even when I thought I was out, I was in, as people who knew me ten, twelve years ago know. I’m sure smarter, better parents of daughters than I have figured it out, but I’m fucking stumped.

I’ve been playing The Legend of Zelda with my daughter, age four. She is viscerally thrilled by the scope and the mystery, and it’s a joy to behold. She wants to know why the monsters are mean. I don’t know what to tell her.

That’s overdramatic, of course. As my dear friends Julia Gfrörer and Stefan Sasse pointed out to me, monsters are a vital embodiment of several crucial ideas — the beasts of nature, harmful everyday things you can’t negotiate, meanness itself. And it is delightful to have raised a child of such industrious empathy, a child so perturbed by meanness and rudeness as her tiny conception of cruelty that it’s the lens through which she views evil itself. But still: the guilt I feel when she chooses the sword.

Come see me read On Immunity out loud tonight

April 16, 2015My friend Maris Kreizman of slaughterhouse90210 put together the very cool thing described below. Come check it out if you’re in or near NYC. I go on early!

—

Special Event: Marathon Reading of On Immunity by Eula Biss

Thursday Apr 16, 2015

6:00 pm – 10:00 pm

THE POWERHOUSE ARENA [Dumbo]

37 Main Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

For more information, please call 718.666.3049

On Immunity tackles with grace and nuance the hot topic of why many fear immunization, delving into myth, philosophy and literature. Authors, parents and enthusiasts join together to read On Immunity from start to finish.

Readers include:

Jason Diamond, Lisa Lucas, Kevin Nguyen, Teddy Wayne, Ariel Schrag, Aryn Kyle, Colin Dickey, Mikki Halpin, Michele Filgate, Rachel Syme, AN Devers, Tyler Coates, Amy Brill, Jazmine Hughes, Parul Sehgal, Rakesh Satyal, Lux Alptraum, Julia Turner, Rachel Rosenfelt, Jaime Green and Maris Kreizman

About On Immunity:

Why do we fear vaccines? A provocative examination by Eula Biss, the author of Notes from No Man’s Land, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Upon becoming a new mother, Eula Biss addresses a chronic condition of fear—fear of the government, the medical establishment, and what is in your child’s air, food, mattress, medicine, and vaccines. She finds that you cannot immunize your child, or yourself, from the world.

In this bold, fascinating book, Biss investigates the metaphors and myths surrounding our conception of immunity and its implications for the individual and the social body. As she hears more and more fears about vaccines, Biss researches what they mean for her own child, her immediate community, America, and the world, both historically and in the present moment. She extends a conversation with other mothers to meditations on Voltaire’s Candide, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Susan Sontag’s AIDS and Its Metaphors, and beyond. On Immunity is a moving account of how we are all interconnected—our bodies and our fates.

About the Author:

Eula Biss is the author of Notes from No Man’s Land, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism, and The Balloonists. Her essays have appeared in the Believer and Harper’s Magazine. She teaches at Northwestern University and lives in Chicago, Illinois.

Suppressive Persons: “Going Clear,” Scientology, and the Appeal of Absolutism

March 29, 2015In Hubbard’s native territory of science fiction, “worldbuilding” is a term used to describe the way writers construct the elaborate sociopolitical, scientific, geographic, and historical framework for the imaginary world in which their stories take place. In a way, Hubbard may well have pulled off the greatest act of worldbuilding in history. Imagine if J.R.R. Tolkien, or George R.R. Martin, or Stan Lee & Jack Kirby had not stopped at merely creating and writing about Middle-earth and Westeros and the Marvel Universe, but overlaid those fictional worlds atop our own until they became indistinguishable not just to their tens of thousands of followers and fans, but to the creators themselves.

It’s reminiscent of Going Clear’s showstopper scene, a Machiavellian game of musical chairs Miscavige imposed on disgraced Church officials to determine their fates, played to the tune of Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” “Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy?” Going Clear’s central assertion is that in art and life alike, thinking people must make that determination, and must be trusted to do it for themselves. It denies its viewers the certainty Scientology itself promises to provide, which may be its most subversive act of all. Heroes to be worshipped, villains to be eradicated—Going Clear asks us to leave them to the pages of fiction and the fever dreams of fundamentalists. Neither are in short supply, inside Scientology or out.

I reviewed Alex Gibney’s Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief for the New York Observer, with a focus on how the film dismantles black-and-white thinking both as journalism/activism and as art. The movie airs tonight at 8pm on HBO, and I hope you’ll watch it.

Identity Crisis

March 22, 2015Back in my Comics Journal messageboard days I was friends with a guy who was kind of a famous or infamous character on that famously or infamously argumentative comics site. This was during my morally indefensible “liberal hawk” period, and we bonded over that among other things, but aside from the hawkishness he always seemed like he was, indeed, otherwise a liberal, like I was. Then during the Obama/McCain election he essentially chose Sarah Palin over our friendship — he went completely berserk over how she was made fun of, he was one of those people who pretended to believe David Letterman made a joke about the Yankees gang-raping one of her daughters and waxed outraged about it for weeks, that kind of thing. Eventually I had to tell him not to contact me anymore, block him from commenting at my blog, and mark all the emails he ever sent me as spam just to get him to leave me alone. This was, you know, six or so years ago and I hadn’t spoken to him since.

After that he got this second career as a “funny” conservative writer for a rightwing online publication, specializing, I guess, in calling black people and anti-racist white people “the real racists” and shit like that. He made a ton of jokes about how Obama eats dogs, Michelle is an ugly person who looks like a Klingon, etc. This whole underground reservoir of racism inside him burst forth like a geyser. It’s horrifying. Every once in a while he’ll spend hours trolling a progressive writer I happen know via Twitter or wherever, and I’ll get in touch and tell my story and warn them they’ll never outlast him if they engage him, best to just ignore him.

Anyway, yesterday I went on twitter, which I’m basically off of now, to monitor reaction to my Scientology article, which I did for a few days. So I saw via retweets and progs making fun of him that he was having some back and forth with another Rolling Stone writer, whose work I admire a great deal. I saw people saying that my former friend had blocked them despite never having interacted with them in any way and wondering if he just preemptively blocked people. So I checked and, sure enough, he’d blocked me even though I hadn’t said a single thing to him in years. Sad.

I bring this up because guess what his avatar was? That’s right, it was the now-canceled Killing Joke homage Batgirl cover with the Joker menacing Batgirl. I just thought to myself, christ jesus, this is what it’s come to now for these people? Taking a cover that was disavowed by its artist, who made it in tribute to a comic that’s been disavowed by its writer, and waving it like it’s the Gadsden flag? Or more accurately the battle flag of the Confederacy? Just because it’s supposedly infuriating to the right people, in this case the dreaded SJWs? Can you imagine anything less macho and more pathetic than building your life around that kind of thing? And they’re the ones who think they’re fighting AGAINST identity politics! It’s like the nerd equivalent of supporting the Duck Dynasty neanderthal.

I actually happen to think there’s a lot of stuff that falls under the “SJW” rubric that is indeed excessive and reactionary in its own right. The Charlie Hebdothing, for example, was almost incomprehensible to me, that you’d look at a pile of corpses and your reaction would be “but the cartoons they drew before they were massacred were really problematic.” People were murdered for drawings! That’s an awesome, in the old-school sense, act to contemplate.Cerebus creator Dave Sim is an insane misogynist and Islamophobe whom I think gets way too much leeway about this to this day, but I can’t imagine having the fucking chutzpah to write a column lambasting him for this the day someone blew his brains out. You know? And I know that for a lot of alternative cartoonists older than, say, 28, the recent thing where people shut down their whole webcomic set in Japan because people on tumblr complained about it was really shocking.

But this? Running around like it’s the second coming of Wertham because a massive corporation recently retooled one of its properties and decided that visually referencing the most unpleasant part of a 27-year-old story was off-brand for its current target demographic, most of whom weren’t even born when that story came out? Insanity. I hope the SJWs make these moral morons cry themselves to sleep every night and wake up with ulcers and teeth ground to shit every morning.