Posts Tagged ‘music’

‘Twin Peaks’: Your A to Z Guide

May 17, 2017MAJOR SPOILER ALERT

A: Angelo Badalamenti

“Where we’re from, the birds sing a pretty song and there’s always music in the air.” That music – as indispensable to to the series as Dale Cooper or donuts and coffee – is the work of Lynch’s longtime musical collaborator Angelo Badalamenti, whose suite of lush leitmotifs made the show sound like a world all its own. Twin Peaks without the composer’s sumptuous synths is like Psycho without Bernard Herrman’s screeching strings, or Jaws without John Williams’s menacing “dun-DUN-dun-DUNs.” This clip of the composer explaining how he and Lynch came up with “Laura Palmer’s Theme” shows how much heart and soul he poured into every note.B: Bob

Lynch was filming a scene for the pilot in which the late Laura Palmer’s mother sits bolt upright and screams. Then he noticed a face in the mirror behind her – the same face he himself saw when its owner, an actor turned set dresser named Frank Silva, crouched behind Laura’s bed to dodge the camera for a different shot. From this sinister coincidence was born Bob, the demonic rapist and murder from the otherworldly Black Lodge who began the series by killing Laura Palmer and ended it by possessing Agent Dale Cooper. Thanks to his malevolent presence, no show has ever been scarier.

Slowdive: Slowdive

May 8, 2017Nature metaphors come so readily to mind when listening to shoegaze—clouds, stars, skies, storms, oceans, whirlwinds, maelstroms—that it’s easy to believe that, like the weather it evokes, it just sort of happens. Invest in the right guitar pedals, put the right breathy spin on your vocals, and bam—instant Loveless, or close enough to fool a stoned and heartsick teenager. It’s as easy as walking out your front door and letting the spring air greet you.

For some bands that may well be all there is to it. But song by song, moment by moment, sometimes even note by note, Slowdive do it better. There’s nothing elaborate in the bassline for “Slomo,” the opening track of their first album in 22 years, given the thick bed of guitars it bounces on. Just seven notes, the sixth of which leaps unexpectedly up an octave instead of continuing the bassline’s descent. Or at the end of “Slomo,” when Rachel Goswell’s voice pulls off a similar trick, first when she takes over lead vocals from Neil Halstead, then when she starts singing them at the very top of her register. At the end of “Go Get It,” Halstead sings two different lyrics laid on top of one another simultaneously, like his conversation with Goswell is over and now he’s talking to himself.

In a genre beloved for its comfortable reliability, all it takes are these small but striking detours to remind us that this glorious noise is the work of human hands and the skill that move them. If there’s a story to Slowdive—the band’s return to active recording together after decades of slowly mounting critical and audience acclaim—beyond the human-interest angle of the return itself, the swerves in the songcraft tell it: This is an album as thoughtful as it is beautiful.

Goldfrapp: Silver Eye

March 30, 2017It takes Alison Goldfrapp more than a full verse into Silver Eye’s leadoff track “Anymore” before she utters a single word with more than one syllable: “You’re what I want. You’re what I need. Give me your love. Make me a freak.” Reductive? Considering her and collaborator Will Gregory—whose past lyrics would gussy up their earthy emotions and desires in hazy surrealism like, “Wolf lady sucks my brain” and, “Now take me dancing at the disco where you buy your Winnebago”—you might be tempted to think so. Prior to “Anymore,” Goldfrapp hid their most verbally explicit expression of lust (“Put your dirty angel face between my legs and knicker lace”) in an elaborate fantasy about a tryst with a traveling carny titled, appropriately enough, “Twist.”

But the direct approach suits this new album, the group’s first since 2013’s Tales of Us. Ever since the pair swapped the John Barry ambience of their debut album Felt Mountain for the electro-glam of its successor Black Cherry, they’ve staked their identity on being able to assume new identities at will. Wanna double down on that sexy “Spirit in the Sky” shimmer? There’s Supernature. Wanna go pastoral? Check out Seventh Tree. Wanna trade Gary Numan and Marc Bolan for the Pointer Sisters and circa-“Jump” Van Halen? Head for Head First. By contrast, Silver Eye is a synthesis—a combination of all the things the group has done well. “Become the one you know you are,” commands a key track, and they’re teaching by example. Who needs many syllables to express something so fundamental?

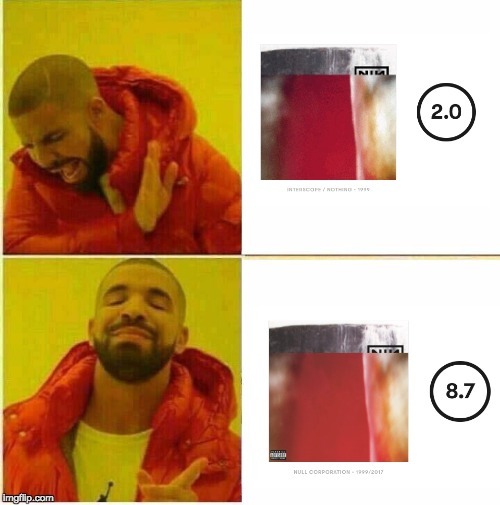

Nine Inch Nails: ‘The Fragile (2017 Definitive Edition)’ / ‘The Fragile: Deviations 1’

January 11, 2017The Fragile arrived a stylistic turning point, emerging at the point where the “alternative” sobriquet fell out of fashion and “indie” achieved dominance. Today, though, reservations about the lyrics’ outré confessionality and the music’s jam-packed, everything-plus-the-kitchen-sink gigantism seem positively quaint. (Don’t care for titanically hyper-produced albums stuffed with uncomfortably intimate and self-mythologizing lyrics about your emotional world falling apart? Tell it to Lemonade.) The Fragile may lack the tightness of Nine Inch Nails’ other highlights: the concise fury of Broken, the inexorable depressive logic of The Downward Spiral, the late-career professionalism of Hesitation Marks. But it takes the emotional distress that gives it its title and transmutes it into something colossal, defiant, and resilient. Listen to it at your strongest or your weakest (and I’ve certainly done both) and it will offer you a sonic signature commensurate with the power of what you feel inside.

tl;dr version:

Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel – “Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)” [Rewind Festival, 17 August 2013]

December 31, 2016“Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)” is the hit in question—a deceptively buoyant poison-pen letter to the musicians who helped make Harley a star. Its verses highlight the star’s melodramatic self-pity (“you’ve broken every code and pulled the Rebel to the floor”), his dismissal of his ex-comrade’s motives as a tedious lust for filthy lucre (“for only metal—what a bore”), his insistence that they’re the ones who wronged him and not the other way around (“it’s from yourself you have to hide”), and his moral and aesthetic superiority (“you’ve taken everything from my belief in Mother Earth…I know what faith is and what it’s worth”).

But the chorus. The chorus! As if fulfilling the promise of the song’s upward-scaling opening guitar filigree and the till-then ironic “ba ba ba”s and “oooh la la la”s, Harley interrupts his exoriations of his former friends by saying “Come up and see me, make me smile / Or do what you want, running wild.” A reference to the Mae West quote he’d drop when his ex-bandmates would ring the buzzer of his upper-floor apartment for a visit, the titular lines run counter to all the other ones—a fantasy of rapprochement, forgiveness, friendship, a return to the carefree days gone by. It’s a fascinating dynamic for a pop song: a chorus that exists in diametric opposition to every verse. A chorus rendered impossible by every single other part of the song.

I wrote about a live performance of “Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)” by Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel for the music tumblr One Week One Band’s year-end special on songs of hope.

The 10 Best Musical TV Moments of 2016

December 20, 2016Vinyl: “Wild Safari” by Barrabás

“Think back to the first time you heard a song that made the hairs on the back of your neck stand up,” Richie Finestra bellows at his record-label employees. “Made you want to dance, or fuck, or go out and kick somebody’s ass! That’s what I want!” Vinyl showrunner Terence Winter had similar goals, but virtually none of the musical elements of his period drama clicked. This despite the imprimatur of co-creators Mick Jagger and Martin Scorsese, who know a thing or two about making magic with music, and supervisors Randall Poster and Meghan Currier, whose previous collaborations with Winter and Scorsese on Boardwalk Empire and The Wolf of Wall Street were all killer, no filler.There was one grand and glorious exception, and it had nothing to do with Jagger swagger. Rather, it was the result of an unlikely alliance between demoted A&R doofus Clark Morelle (Jack Quaid) and his mail-room buddy Jorge (Christian Navarro). When the latter takes Clark to an underground dance club, they enter in slow motion to the ecstatic sounds of the 1972 proto-disco song “Wild Safari” by Barrabás. The killer clothes, the fabulous dancing, the beatific smiles on the faces of beautiful people, the irresistible rhythm, the rapturous “WHOA-OH-OH” of the chorus, the sense that an entire world of incredible music has existed right under his nose — you can feel it all hit Clark right in the serotonin receptors, and damn if it doesn’t hit you, too. Perhaps my favorite two minutes of TV this year, this sequence demonstrates the life-affirming power and pleasure of music.

You won’t fool the children of the revolution

November 25, 2016(“Raw Power” comes on in the car)

Me: This is a band called Iggy & the Stooges. The lead singer’s name is Iggy Pop, and he did all kinds of crazy things. He smeared himself in peanut butter, he’d break bottles and cut himself up, he covered himself in honey and sprinkled glitter on himself, he’d even just walk right on top of the audience.

My 5 1/2 year old: They could get a concussion! Did he wear anything crazy too?

Me: He was really muscular, and he’d come out in no shirt and, like, very tight silver pants.

My 5 1/2 year old: That’s crazy! Were you there, Daddy?

Me: Was I there? No. This was in the early ’70s, so…like, 45 years ago, almost. Before I was born.

My 5 1/2 year old: Then how do you know about it? How do you know all about these things if you weren’t there?

Me: Because it was very famous, and people wrote all about it. You can read books that tell you all about different bands from a long time ago.

My 5 1/2 year old: Tell me EVERY STORY about EVERY CRAZY THING anyone did in EVERY BAND, PLEASE!

“Westworld,” and When TV Uses Pop Music to Do Its Emotional Heavy Lifting

November 7, 2016Maeve’s walk through the Westworld theme park’s behind-the-scenes house of horrors is the moment we’ve all been waiting for. It’s the instant in which one of Westworld’s unfortunate, unwitting robots receives undeniable, unforgettable confirmation that their life is a lie. It’s a crushing concept all on its own, and the guided-tour-of-hell structure of the scene adds to the pathos. By rights it should stand alone as one of the series’ most powerful moments.

And yet, Westworld’s treatment of it falls flat. Like park technicians fiddling with a host’s intelligence or empathy on their control panels, the show’s filmmakers artificially increase the sequence’s tear-jerking levels by soundtracking it with a chamber-music version of the closing track on one of the most acclaimed albums of all time: “Motion Picture Soundtrack,” the achingly sad conclusion of Radiohead’s electronic-music breakthrough Kid A. It’s not the first time the hyperactively overscored series has relied on the band, having previously gone to the Radiohead well with their suburban-ennui anthem “No Surprises.” Hell, it’s not the first time it did so in this episode, which opens with a similarly heavy-handed accompaniment by a player-piano version of the band’s ode to falseness, “Fake Plastic Trees.” But it is the show’s most egregious example yet of using a song with preexisting cultural clout to do its emotional work — a syndrome we’re seeing, or hearing, with increasing frequency as Peak TV prestige dramas attempt to cut through the clutter and grab viewers, or listeners, by the heartstrings.

Rather than let the power of the scene emerge on its own, Westworld leans on a preexisting work of art to doing the heavy lifting for it. It’s a cheat, a shortcut to resonance. That particular work of art has far more cultural purchase, impact, and history than a first-season TV show. Even if you don’t rate Radiohead, substitute the gut-wrenching classic-album closer of your choice — “Purple Rain” or “Little Earthquakes” or, to cite an artist Westworld’s already employed to dubious effect in that over-the-top orgy scene last week, “Hurt”— and you’ll get the point.

Over at Vulture, I went long on how shows like Westworld, Stranger Things, and even The Americans have used preexisting pop music as a cheat code to score emotional points they haven’t earned. I also talked about shows that have done pop music cues right, from The Sopranos and The Wire to Lost to Halt and Catch Fire and The People v. O.J. Simpson. It’s basically a prose version of what Chris Ott and I talked about on his Shallow Rewards podcast a few weeks ago. I quite liked writing this piece and I hope you enjoy it.

Shallow Rewards – The Song Remains the Shame: Mr. Robot and Stranger Things

September 26, 2016I was delighted to become (I think) the first ever recurring guest on Shallow Rewards, the enormously insightful podcast from music criticism’s adulte terrible Chris Ott, to discuss the use of standout pop songs on the soundtracks of prestige television shows. We focus on Mr. Robot and Stranger Things (so watch out for spoilers) but touch on Halt and Catch Fire, The Sopranos, and The Wonder Years, with plenty of digressions into film soundtracks and film in general (Cameron Crowe, Martin Scorsese, SLC Punk, Under the Skin) as well. Chris is one of my favorite critics of any kind and it’s a pleasure talking to him. I hope you enjoy the results!

Shallow Rewards: Not Yr 90s with Sean T. Collins

July 21, 2016I appeared on my favorite music podcast (and my favorite podcast period), Chris Ott’s Shallow Rewards, to discuss how the critical narrative of the 1990s has distorted the reality of how the era’s music, “alternative” and otherwise, functioned, flourished, and failed. There are substantial digressions about the overall state of arts criticism and journalism in there, too. Nobody does a better job than Chris of editing a podcast for maximum impact — honestly, it’s not even close. Moreover his work has been a huge inspiration and influence for me, and it was an honor to be a guest. Please listen!

Words and Guitars tonight

May 19, 2016I’ll be reading Hottest Chick in the Game, me and Andrew White’s comic about Drake and friends, at the HiFi Bar in NYC at 8pm tonight as part of Zachary Lipez & Michael Tedder’s Words and Guitars reading series. A whole bunch of other luminaries will be reading too, so heed the words of the man himself and come thru!

The HiFi Bar is located at 169 Avenue A between East 10th & 11th in Manhattan. I hope to see you there!

The 10 Best Underworld Songs

March 18, 20169. “Always Loved a Film” (from Barking, 2010)

From “lager lager lager” to “crazy crazy crazy” to “you bring light in,” repetition has always figured prominently in singer Karl Hyde’s lyrics. But it’s never done so more revealingly than in “Always Loved A Film,” a standout track from their last studio album, 2010’s Barking. The words that get the most play here? “The rhythm” and “Heaven,” two concepts that for Underworld are largely synonymous. The track itself is one of the most conventional verse/chorus/verse affairs in their discography (they get reflexively tagged by critics for their traditional rock-songwriting style way more often than they actually write traditional rock songs), with guest producers Mark Knight and D. Ramirez adding a crunchy texture that befits the song’s structural solidity. Like “Two Months Off,” it’s a love song that uses the imagery of light radiating outward in a sleight-of-hand substitution for the intense emotion being directed inward. This time, though, the celestial metaphor is brought down from the sky to the earth by anchoring it to the memory of walking down a hot summer street: “The rhythm of keys swinging in your hand, the rhythm of light coming out of your fingers.” When the chorus hits, it’s a million miles from the elusive and inscrutable lyrics Hyde usually indulges in, hitting as hard and direct as anything on pop radio at the time — “Heeeeaven, heavennnnnnn — can you feel iiiiit?” could have been a Lady Gaga lyric. The highlight, though, may be the acoustic-guitar-accompanied bridge, which adds an element of uncertainty — “I don’t know if I love you more than the way you used to love me” — a la George Harrison’s “You’re asking me will our love grow / I don’t know, I don’t know” from “Something.” Both songs trust love to be big enough to accommodate doubt, bright enough to risk some shadow.

In honor of Underworld’s terrific new record Barbara Barbara, we face a shining future, I named The 10 Best Underworld Songs for my Stereogum debut.

Music Time: Underworld – Barbara Barbara, we face a shining future

March 15, 2016Let’s talk about love—with Underworld, you kind of have to. Though still best known for shouting “lager, lager, lager” in their epochal 1996 hit “Born Slippy.NUXX,” the long-running dance duo, consisting of singer-lyricist-multi-instrumentalist Karl Hyde and producer Rick Smith, have quietly but persistently placed matters of the heart at the center of their best songs. Their breakthrough single “Cowgirl” pledged “I wanna give you everything,” robotically chanting the final word like a mantra for emphasis. “Jumbo,” the buoyant highlight of 1999’s Beaucoup Fish, took a (literally) sweeter approach, with singer Karl Hyde purring “I need sugar” when “I get thoughts about you.” And despite the involvement of a series of guest producers whose work never quite gelled, UW’s last studio album Barking was held together by a chain of out-and-out love songs, from its singles “Scribble” to its tremulous closing ballad “Louisiana” (“When you touch me, planets in sweet collision”). Regardless of their reputation for turning late-night urban-hedonism anthems into festival-filling crowdpleasers, Underworld remain romantics at heart.

Nowhere is this more apparent than on Barbara Barbara, we face a shining future—perhaps because Smith and Hyde’s own creative romance needed rekindling.

“Vinyl” thoughts, Season One, Episode Five: “He in Racist Fire”

March 15, 2016Five episodes into Vinyl’s initial spin and one thing is clear: This show hates Jethro Tull.

Remember a few episodes ago, when Richie Finestra got so incensed by the “Aqualung” impresarios’ flute-laden prog rock that he yanked the record off the turntable and smashed it over his knee? This week, merely presenting our antihero and his A&R right-hand man Julie with a group of I Can’t Believe It’s Not Ian Anderson renaissance-faire goobers was enough to get the Ivy League tryhard Clark (“I graduated from fucking Yale!”) demoted to sandwich gofer. Look, we believe Metallica should have won that Grammy 27 years ago too, but after the second season of Fargo used “Locomotive Breath” to score an amazing gang-war montage, this should all be water under the bridge. You’re really gonna listen to “Cross-Eyed Mary” and argue that these dudes were everything wrong with Seventies rock & roll, while Loggins & Messina walk free? Fight the real enemy, folks.

I reviewed this week’s Vinyl and defended Jethro Tull for Rolling Stone.

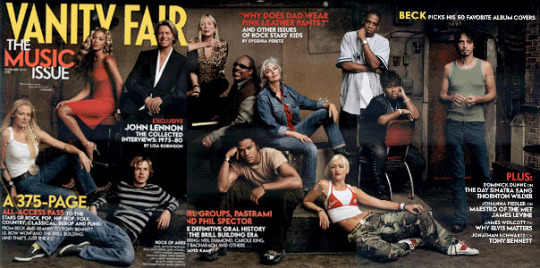

Goodbye, Bowie Loves Beyoncé

March 12, 2015

I started bowielovesbeyonce, my first tumblr, in February 2009. I always said that if the two of them ever took a picture together, I’d happily retire the tumblr, my work done. Tonight, searching for header image for the site’s mobile layout, I discovered that they’d taken two pictures together — at the Met Gala a year ago, and on the cover of Vanity Fair fourteen years ago, eight years before I even started this thing. I’m stunned and chagrined that I missed these photos for all this time, but still, I’m so happy to see Bowie and Beyoncé together. I love them both; they mean so much to me.

I’m going to go ahead and keep that promise to myself. It’s a shock to the system, coming coincidentally just one day after I decided to stop using twitter except for very minimal professional upkeep — I’ll have so much free time in my day (and free space on my dash) that I won’t even know what to do with. But this was the plan all along, and I want to see it through. And who knows: If David can come back after a decade of silence, anything is possible.

All thanks to David Bowie and Beyoncé Knowles-Carter, my very favorite pop stars of all time. You have given me a better life.

“The Americans” thoughts, Season Three, Episode Seven: “Walter Taffet”

March 12, 2015Fleetwood Mac’s 1977 album Rumours is a crystalline collection of immaculately produced pop-rock that has sold in the neighborhood of 40 million copies. That’s approximately 8 million copies per each of the five members of the band whose romantic partnership ended during the album’s recording. Given that there were only five people in Fleetwood Mac, including a pair of couples, that’s one hellacious track record. Count ‘em: Guitarist Lindsey Buckingham and his longtime partner Stevie Nicks, two of the band’s three main songwriters, broke up acrimoniously. The third songwriter, Christine McVie, left her husband, bassist John McVie — for the group’s lighting director. Finally, drummer Mick Fleetwood got a divorce from his wife Jenny Boyd. (PS: Boyd had conducted a lengthy affair with the band’s ex-guitarist Bob Weston; Fleetwood would go on to have a secret relationship with Nicks, which ended when he broke up the marriage of Nicks’s best friend by having an affair with her. BuzzFeed’s Matthew Perpetua has the best summary of the turmoil if you’re searching for a scorecard.) Lindsay, Stevie, and Christine all chronicled their changing fortunes with savage honesty and/or dizzying romanticism in the songs that formed the album. And in the only instance of the entire group collaborating as songwriters, all five band members co-wrote the record’s centerpiece, classic rock’s most vicious anthem of romantic recrimination: As they all fell apart, “The Chain” quite literally kept them together.

It’s well worth thinking about Fleetwood Mac in the context of The Americans. In a sense, the two are inseparable, and not just becauseMatthew Rhys is Lindsey Buckingham’s spitting image: The show’s pilot began with an eight-minute espionage sequence set to an extended remix of“Tusk,” Buckingham’s bizarro paean to sexual paranoia. And tonight’s climactic use of “The Chain” will, yes, keep them together as well. But the songs are on the soundtrack for a reason. Long before Mick’s opening stomp emerged from your speakers tonight, this was a show obsessed with the ways in which couples in varying degrees of estrangement could nevertheless come together to achieve something greater than they ever could individually. “Walter Taffet,” this week’s episode, contained enough examples to make the Mac’s Behind the Music blush.

I reviewed Fleetwood Mac tonight’s episode of The Americans for the New York Observer.

They said you were hot stuff: on the “Baby’s On Fire” sequence from Velvet Goldmine

January 5, 2015I Was a Teenage Velvet Goldmine Skeptic. Not quite teenage, I suppose — I’d already turned 20 by the time of the film’s autumn 1998 release — but my musical mindset was still adolescent in essence. Precariously poised between poseurs and mainstream morons, I believed, there existed a sweet spot of authentically alternative art, of real rock and roll rebellion. This was a place you could live, provided you worked relentlessly to refine your taste to its essentials, and then never, ever fucking budged. One and a half post-poptimism decades later I’m sure I don’t need to tell you how needlessly dreary and exhausting an approach this is, but my own Pauline conversion was still a few years in the future. That road to pop-cultural Damascus had many side streets. But if you were to retrace the route — starting with My First Pop Divas Kylie and Beyoncé, working back through electroclash and the Grand Theft Auto: Vice City soundtracks, traversing all the ‘80s pop and ‘70s rock I’d never before gone near, and converging at David Bowie, the artist whose breathless, liberating adoption and deletion of influences and imagery at opened up my avenues to all of the above — the road would begin with a chance late-night Cinemax channel flip and my second encounter with Todd Haynes’s glam fantasia Velvet Goldmine. It’s no exaggeration to say that that viewing changed my life. The only thing it had in common with my first viewing of the film — a head-scratching, yawn-suppressing affair in the campus art-house during its brief bomb of a theatrical run, at which I pronounced it an overinflated, pointlessly complex dud that committed the cardinal sin of not rocking hard enough — was this: I loved the “Baby’s On Fire” sequence, the movie’s centerpiece, its beating heart, its throbbing loins.

Famously, Velvet Goldmine is to David Bowie what Citizen Kane (from which it stole its structure) is to William Randolph Hearst. To use a more recent example, and a more accurate one given how both films center a fictional, emotionally overwhelming relationship between two men, it is to Bowie what The Master is to L. Ron Hubbard. In place of Joaquin Phoenix’s giggling alcoholic damage case, VG puts forward Ewan MacGregor’s American rock’n’roll animal Curt Wild as the foil to its central celebrity stand-in, Jonathan Rhys Meyers’s Brian Slade. Though primarily an Iggy Pop manqué, Wild will, throughout the course of the movie, incorporate elements of Lou Reed’s biography, Oscar Wilde’s name, Kurt Cobain’s name andlooks, and Bowie’s own post-glam Berlin period. The moniker for Meyers’s Bowie figure similarly references fellow glitter luminaries Brian Eno, Bryan Ferry, and the band Slade; if we were to pick apart “Maxwell Demon and the Venus in Furs,” Brian’s alien-messiah persona and his house band, we’d be here all night.

This Russian nesting-doll layering of references to icons of rock, film, and literature is an annotator’s dream, to be sure. But more importantly, it enables Haynes to make a movie not about Bowie, Iggy, and glam, but about the idea of them, doing so by constructing them from a continuum of related ideas. Velvet Goldmine is about artifice as art and fandom as fantasy, and a love letter to the artists who introduced a young Haynes to these sensations as he came to terms with life as a young gay man. The “Baby’s On Fire” sequence is where that letter gets sealed with a kiss.

I wrote about my favorite sequence from one of my favorite movies, the Velvet Goldmine montage sequence scored by Jonathan Rhys Meyers/Venus in Furs cover of Brian Eno’s “Baby’s on Fire,” for One Week One Band’s special soundtrack spectacular.

BLACK FRIDAY: HALLOWEEN MIX 2014

October 17, 2014i made a mix of scary songs for frightened people // download it here // track list in lyrics field in metadata // listening suggestion: let it all take you by surprise // your childhood is over

Oral history lesson

May 1, 2014A couple weeks ago Jessica Hopper published an oral history of Hole’s Live Through This, and it had been a very long time since I reacted to a work of criticism so intensely so quickly.

For one thing, speaking as a writer who’s done one in the past, this is an achievement in using the oral-history form to reveal information, rather than aid in cloaking it through self-mythologization. It’s so easy to do that with these things. Shit, it’s baked into the premise of the enterprise: Look at my proximity to all these people’s proximity to greatness!

But it’s not that Hopper doesn’t include all the choice nugs you’d want in an oral history — you know, anecdotes about meeting RuPaul while hammered at the SNL afterparty, differing accounts of how badly Courtney Love wanted to work with Butch Vig, etc. It’s that she treats it not just as a history of a cool thing, but as reporting on that thing. She digs into how the studio was selected, how the personnel came together, what the schedule was like. She digs into the rock climate at the time, the (limited) involvement of Billy Corgan and Kurt Cobain, the (profound) influence of Siamese Dream and Nevermind. She digs into drug use, who was doing what and when. She talks to band members, producers, label people. She lets Love hoist herself by her own petard when that’s called for, but she also lets her emerge, then and now, as someone who had a very clear artistic goal and worked, successfully, to achieve it. Inner torment and commercial ambitions and improved songwriting chops and a better rhythm section and working with a guitarist with little self-confidence and hiring skilled producers and developing a workday routine and navigating the demands of other prominent artists in the field with whom she was close — it all went in and that record came out, and Hopper gets it all down. I suppose she’s lucky that she got such a forthcoming group of interviewees, since god knows that’s rare, but luck’s a fundamental part of a good piece too.

I didn’t listen to Hole in the alt-’90s heyday; didn’t buy the “Yoko” nonsense either, that just didn’t seem to cut any more ice here than it does with actual Yoko. And there’s no way to be judgmental about Love as a parent without being more so about the one who isn’t there anymore at all, so I think I gave that a pass over the years as well. Point is I didn’t have much riding on reading this either way. But what a fascinating document of the making of a work of art, and what an inspiring example of how to write about art. It makes me want to work harder.

Relocation

December 11, 2013All my Vorpalizer posts about comics and genre art are now housed at http://seantcomics.tumblr.com and http://seantculture.tumblr.com . Thanks.